Cirrhosis with portosystemic shunting is associated with malnutrition, which is the most frequent, yet potentially reversible complication that worsens with disease progression and adversely affects outcome in these patients.1-5 Malnutrition in cirrhosis is associated with major complications that include sepsis, uncontrolled ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome that develop in 65% of malnourished patients versus 12% of well-nourished patients.4,6-10 Several recent reviews have discussed the current clinical problems and therapy for malnutrition in cirrhosis.11-13 However, the major limitation of these is the lack of focus on the recent advances and potentially exciting data from diverse fields besides hepatology. This review focuses on the current understanding of malnutrition and the newer molecular pathways and targets that are likely to result in novel and specific therapies to reverse its components. Malnutrition in cirrhosis consists of a loss of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue mass. Even though it is being recognized that this combination should be defined as cachexia,14,15 the predominant loss of muscle mass in cirrhosis suggests that sarcopenia or loss of skeletal muscle mass is the primary nutritional consequence.16,17 In patients with cirrhosis, the prevalence of malnutrition characterized by loss of lean body mass and diminished skeletal muscle weight is estimated to be between 20% to 60% in different studies.5,18-21 Most studies have focused on quantifying lean body mass using different instruments, but the skeletal muscle constitutes between 40% and 50% of the lean body mass.22 More precise measures of skeletal muscle mass that are being recognized are the direct measures using imaging techniques.16,17 Skeletal muscle loss in cirrhosis worsens with advancing severity of liver disease as measured by Child’s score and the development of portosystemic shunting.19,23-25 There has been limited success using several nutritional and other interventions in reversing malnutrition and low skeletal muscle mass in cirrhosis.1,2,23,26,27 Only partial improvement in anthropometric measures and body weight occur when enteral nutrition or parenteral amino acid mixtures are given.28,29 Neither recombinant growth hormone nor insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF1) in human and animal models of cirrhosis were able to result in complete recovery of skeletal muscle mass.30-32 These poor results are likely related to the limited understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for diminished muscle mass in cirrhosis and portosystemic shunting.1,33 Several factors may contribute to this and include the predominantly descriptive nature of the human studies, heterogeneity in the definitions for malnutrition, limited mechanistic studies on skeletal muscle loss in cirrhosis, and the preponderance of publications on skeletal muscle biology in nonliver journals.34,35 Despite the number of publications in this area, there are few studies that have reconciled the recent and exciting data obtained from studies on skeletal muscle biology into our current understanding of malnutrition in cirrhosis.22,36 The present review aims toward integrating our current understanding of the clinical consequences, mechanisms, and therapeutic targets and approaches toward reversing the major complication of cirrhosis, sarcopenia, or loss of skeletal muscle mass.

Recent studies in animal models and cell culture systems have contributed significantly to our understanding of potential mechanisms responsible for sarcopenia in portosystemic shunting in cirrhosis.37-42

Our understanding of the metabolic processes in cirrhosis, skeletal muscle, and whole body protein, fat, and carbohydrate metabolism has increased over the past 2 decades, during which time liver transplantation has become a viable and definitive treatment option for end-stage liver disease. Several questions, however, remain unanswered. These include the precise definition of malnutrition in cirrhosis; prevalence of malnutrition in cirrhosis that is affected by the method used to define malnutrition; the impact of malnutrition on outcome before, during, and after liver transplantation; the available therapeutic options; and the outcome in response to these interventions. Additionally, recent exciting and novel data from the authors’ laboratory, and that of others, to identify the role of molecular signaling pathways are expected to provide novel insights into the management of patients with cirrhosis.36,43

MALNUTRITION IN LIVER DISEASE: DEFINITIONS

There is wide heterogeneity in the definition of malnutrition in cirrhosis, primarily because adult malnutrition is not well defined. In children, malnutrition is clearly defined as predominantly protein malnutrition or kwashiorkor and combined protein and calorie malnutrition or marasmus. In humans, most proteins are located in the skeletal muscle,44-47 and we have, therefore, defined clinical adult protein malnutrition as primarily skeletal muscle loss. Energy malnutrition is more difficult to define clearly, but because adipose tissue is the largest repository of calories, adult fat malnutrition can be defined as a reduction in whole body fat mass. Loss of skeletal muscle mass is also known as sarcopenia, even though this term has traditionally been used to define loss of muscle mass with aging.14,15 More recently, other terms have been used that include cachexia, which is defined as loss of both muscle and fat mass that is not responsive to providing adequate dietary intake, and precachexia, which is based on the percentile values of the measured muscle and fat mass compared with controls.14,15 However, it must be reiterated that these consensus definitions are being developed, but their relevance to the complex metabolic and nutritional derangements in cirrhosis have not been evaluated. It may, however, be summarized that based on our current understanding, malnutrition in cirrhosis comprises reduced muscle mass and strength, called sarcopenia, as well as loss of subcutaneous and visceral fat mass that may be called adipopenia. The term hepatic cachexia can be used to define the proportionate loss of both muscle and adipose tissue mass. Finally, the rapid increase in prevalence of fatty liver–related cirrhosis is increasing the number of patients who have sarcopenic obesity characterized by a disproportionate loss of skeletal muscle mass with preserved or increased visceral or subcutaneous adipose tissue mass. Given these reasons, it may be best to avoid the term, malnutrition in cirrhosis, because it can be used to refer to sarcopenia, adipopenia, cachexia, precachexia, obesity, sarcopenic obesity, and micronutrient deficiencies. Precision in definition will permit a clear definition of the patient population being studied and the outcome measures being quantified. Given the lack of such a consensus definition in patients with cirrhosis, the authors have defined these terms in the specific population of patients with cirrhosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of malnutrition in cirrhosis

| Author/Year | n | Definition of Malnutrition | Prevalence (%) | Cause of Cirrhosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberino et al,19 2001 | 212 | TSF | Severe 34 | Alcohol |

| MAMA | Moderate 20 | Viral | ||

|

| ||||

| Akerman et al,59 1993 | 104 | TSF <fifth percentile | 33 <fifth percentile | Alcohol |

| MAMC <fifth percentile | 43 | Viral | ||

| Primary biliary | ||||

| Sclerosing cholangitis | ||||

|

| ||||

| Alvares-da-silva & Reverbel da,4 2005 | 50 | SGA | 28 | All causes |

| Prognostic nutritional state | 28 | |||

| Handgrip strength | 63 | |||

|

| ||||

| Figueiredo et al,74 2005 | 79 | Body cell mass | 31.6 | Alcohol |

| TBF | Viral | |||

|

| ||||

| Caly et al,71 2003 | 77 | TSF | 71 | Alcohol |

| Albumin | Viral | |||

|

| ||||

| Caregaro et al,72 1996 | 120 | Anthropometric | 34 | Alcohol |

| Visceral | 81 | Viral | ||

|

| ||||

| de Carvalho et al,76 2010 | 300 | Anthropometric | 75 | All causes |

|

| ||||

| Lehnert et al,75 2001 | 50 | BIABCM | Child A, 71 | Viral |

| TBF | Child C, 81 | Primary biliary | ||

| Autoimmune | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hasse et al,49 1993 | 20 | Immunologic | 59 | Viral |

| SGA, moderate | 70 | Primary biliary | ||

| SGA, severe | 15 | Wilson disease | ||

|

| ||||

| Hehir et al,77 1985 | 13 | Anergy | 58 | All causes |

| Lymphocyte | 92 | |||

| Albumin | 62 | |||

|

| ||||

| Loguercio et al,78 1996 | 184 | Skinfold thickness | Child A, 8 | All causes |

| Child B/C, 26 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mendenhall et al,68 1984 | 363 | Clinical diagnosis | 100 | Alcohol |

| Viral | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mills et al,79 1983 | 30 | DTH | 29 | Alcohol |

| Vitamin deficiency | 43 | Viral | ||

| MAMC | 13 | |||

|

| ||||

| Morgan et al,65 1996 | 60 | Anthropometric | 29 | Alcohol |

| BIABCM | Viral | |||

| Primary biliary | ||||

| Autoimmune | ||||

|

| ||||

| Peng et al,18 2007 | 268 | Indirect calorimetry | 51 | All causes |

| Grip strength | ||||

|

| ||||

| Reisman et al,80 1997 | 1015 | Clinical nutritional state | 33–60 | Alcohol |

| Viral | ||||

| Primary biliary | ||||

| Autoimmune | ||||

|

| ||||

| Roongpisuthipong et al,73 2001 | 60 | Visceral protein | 45 | Alcohol |

| DTH | 22 | Viral | ||

| Ideal body weight | 13.3 | |||

|

| ||||

| Sam and Nguyen,81 2009 | 114,703 | Clinical diagnosis | 6.1 (1.9 control) | Alcohol |

| Viral | ||||

| Primary biliary | ||||

| Autoimmune | ||||

|

| ||||

| Tai et al,82 2010 | 36 | MAMC | 50 | Alcohol |

| SGA | 40 | Viral | ||

| Primary biliary | ||||

| Sclerosing cholangitis | ||||

Abbreviations: BIABCM, bioelectrical impedance analyzer measured body cell mass; BIATBP, bioelectrical impedance analyzer measured total body protein; BMI, body mass index; SGA, subjective global assessment; TBF, total body fat; TBP, total body protein; TSF, triceps skinfold thickness.

Summary: Eighteen studies, with a total of 3041 of subjects enrolled, measure malnutrition by a variety of methods, including SGA, MAMC, TSF, BIA, and clinical assessment. The prevalence of malnutrition ranges from 6.1% to 100.0%. Cause of cirrhosis included alcohol, viral, primary biliary, autoimmune, sclerosing cholangitis, and Wilson disease.

METHODS TO ASSESS MALNUTRITION IN CIRRHOSIS

As previously stated, most publications on malnutrition in cirrhosis use heterogeneous definitions. Standard nutritional assessment instruments use laboratory tests, such as prothrombin time; albumin; prealbumin; transferrin; creatinine height index; and on tests of immune function, such as the delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.48-50 Because end-stage liver disease or cirrhosis confound the common measures of nutritional status, their utility in these patients is reduced. Patients with cirrhosis have significant impairment in their hepatic synthetic function that results in low serum albumin, prealbumin, transferrin levels, and prolonged prothrombin time. These levels will result in an overestimation of the prevalence of malnutrition in these patients.51,52 Renal impairment is common in cirrhosis, making the creatinine height index an imprecise measure of malnutrition.53 Anthropometric measures are affected by altered fluid status caused by ascites, peripheral edema, diuretic and salt intake, and concomitant rental failure that makes weight changes difficult to interpret.54,55 Skinfold thickness that measures subcutaneous fat mass, upper-arm measure of muscle area (midarm muscle area), and subjective global assessment (SGA) has additional limitations, including interobserver variability.56,57 Furthermore, with the change in demographics and socioeconomic patterns, there are changes in the normal values, and concurrent norms should be used for defining criteria for sarcopenia and cachexia.58 Finally, the anergy in cirrhosis makes delayed-type hypersensitivity an inaccurate gauge of malnutrition.51,59

Several indirect, in vivo methods have been used to quantify body composition in cirrhosis. These methods include total-body electrical conductivity, bioelectrical impedance, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, deuterium dilution, air displacement plethysmography, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy.60-62 These methods are based on the principle that at least 2 components exist in the body fat mass and fat-free mass that is essentially water, protein, and mineral.63 By determining the whole body weight and fat mass, it is assumed that the remaining weight is nonfat or lean mass. Because 40% to 60% of lean body mass in humans and rodents is contributed by skeletal muscle mass, quantification of lean body or fat-free mass is considered to be a measure of whole body skeletal muscle mass.64 There are also concerns expressed about the 2-compartment model obtained from these studies, and alternative 3-component and 4-component models have been proposed.63,65-67 These multi-component models suffer from limitations in cirrhosis because of the alteration in hydration, bone mineralization, and fluid shifts. Hence, there seems to be no true gold standard or reference technique to quantify malnutrition in cirrhosis. The choice of application is based on cost, logistics, availability, and the need for accuracy and segmental body composition. Based on published studies on malnutrition, the authors’ definitions of protein malnutrition to be reflected by skeletal muscle mass and fat malnutrition quantified by the loss of subcutaneous and visceral fat mass as well as altered thermogenesis seem most clinically relevant and can be applied at the bedside.

Recently, psoas muscle area quantified on a single section of computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen at the L3/4 level has been validated as a reliable, noninvasive measure of reduced whole body skeletal muscle mass in cirrhosis.16,17 The authors have observed this to be equally reliable for quantifying visceral fat mass on the same section. Because CT of the abdomen is routinely used to screen for lesions in patients with cirrhosis, this can also be used to quantify skeletal muscle and fat mass in these patients. Despite its simplicity, cost and irradiation are 2 considerations that need to be taken into account when using this method.

PREVALENCE OF MALNUTRITION IN CIRRHOSIS

A high prevalence of malnutrition has been reported in patients with cirrhosis in studies in which visceral protein status and immunologic measures are included in the nutritional assessment.48,68,69 The prevalence of nutritional disorders is lower when malnutrition is diagnosed by anthropometric measures only.54,55 Differences in the cause and severity of disease also affect the estimated prevalence of malnutrition in cirrhosis.48,70-73 A review of studies published that examined the prevalence of malnutrition using defined criteria is shown in Table 1.4,18,19,49,59,65,68,71-82 It can be summarized from these data that the prevalence of malnutrition depends primarily on the definition chosen, cause of the liver disease, the stage of the disease, and the methods used to quantify malnutrition. Anthropometric measures have been considered to be most dependable; using only these criteria, the prevalence is significantly lower than previously estimated. The lowest estimate from the largest study in 114,703 hospitalized patients with cirrhosis compared with hospitalized patients without cirrhosis showed a prevalence of 6.1% in cirrhosis compared with 1.9% in controls.81 The major limitation of this study is that malnutrition was diagnosed imprecisely based on a clinical discharge diagnosis. The investigators acknowledge the limitations but suggest that their data support previous published literature on the high (more than 4 fold) prevalence of malnutrition in cirrhosis compared with patients without cirrhosis. Other studies have confirmed that using a combination of biochemical and immunologic studies overestimates the prevalence of muscle and fat loss as estimated by clinical and anthropometric methods.19,72 Given these observations, it would be appropriate to have a standardized method of assessment of protein and fat malnutrition in cirrhosis. An extensive review of the data suggests that the modified SGA that is appropriate in cirrhosis and precise upper-extremity anthropometric measures may be the best available option.4,49 A recent study by the authors’ group in 97 hospitalized patients has shown that grip strength and SGA remain the most feasible instruments in assessing the nutritional status and outcome.

These data suggest that based on the definition of the specific component of malnutrition, an appropriate measurement instrument should be chosen. Increasing interest in imaging methods is because of the ability to distinguish the reduction of skeletal muscle and visceral and adipose tissue mass. However, functional measures of muscle strength remain one of the most relevant measures of sarcopenia.83

SEVERITY OF LIVER DISEASE WORSENS SARCOPENIA

Malnutrition has also been related to the severity of liver disease as estimated by Child’s score.73 Several modifications of the original Child’s score have been used, including the Child-Turcotte, Campbell Child, and Pugh-Child scoring systems.80 In the Pugh modification, the nutritional status was replaced by prothrombin time; the rationale for this was that the nutritional assessment used in the other versions had a significant subjective evaluation, whereas the prothrombin time in combination with serum albumin provides a more objective measure of long-term nutritional evaluation.84 However, as has been discussed earlier, these are truly measures of hepatic function and are likely to show greater abnormality with worsening severity of liver disease. The authors have specifically excluded those investigators who used the Child-Turcotte and Campbell Child scoring system because these have nutritional evaluation incorporated into them and are, therefore, biased in favor of a higher prevalence of malnutrition in advanced disease. In 3 published studies that evaluated the impact of severity of underlying liver disease as measured by the Child-Pugh scoring system showed that there is evidence of malnutrition as assessed by grip strength, body cell mass, body fat mass, and ideal body weight early in the course of the disease.73,74,85 These measures of nutritional deficiency become worse with progressive severity of liver disease.73,74,85 Other measures of severity of liver disease, including the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, have not been systematically assessed for their relation to the severity of sarcopenia, cachexia, or malnutrition.

These observations suggest that clinical and anthropometric measures of loss of muscle mass and fat mass are common in cirrhosis and worsen with the progression of liver disease.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF MALNUTRITION IN CIRRHOSIS

For practical clinical purposes, the impact of malnutrition in cirrhosis on outcome can be examined by the effect of skeletal muscle loss on survival and complications of cirrhosis. With the availability of liver transplantation, aggressive intensive care, antibiotics, renal support, and endoscopic interventions to prevent and treat the complications of cirrhosis, there is a resurgence of interest in the nutritional management of these patients. Several studies have consistently shown that malnutrition in cirrhosis affects the survival and the development of the complications of cirrhosis.

Malnutrition and Survival in Cirrhosis

Several investigators have examined the impact of malnutrition, primarily using instruments that measure sarcopenia, and observed that worsening severity of muscle loss is accompanied by higher mortality (Table 2).3-5,10,16,17,76,86-91 It is interesting that despite a large number of studies across the world demonstrating that sarcopenia and malnutrition worsen survival in cirrhosis, no studies have documented improved survival with reversal of sarcopenia. In this context, it is interesting that the authors’ studies on reversal of sarcopenia after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) have demonstrated better survival after TIPS in patients in whom skeletal muscle mass increased compared with those in whom skeletal muscle mass did not change or became less.92

Table 2.

Impact of malnutrition on survival in cirrhosis

| Author/Year | n | Pretransplant Malnutrition (%) | Posttransplant Survival |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alvares-da-Silva & Reverbel da,4 2005 | 50 | SGA 28 | 20.7% mortality in subjects with PCM vs 0% without PCM, assessed by HG; P>.05 for HG vs other variables; |

| PNI 19 | 21.4% mortality in subjects with PCM vs 8.3% without PCM, assessed by SGA; P>.05; | ||

| HG 63 | 0% mortality with and without PCM when assessed by PNI; P>.05 | ||

|

| |||

| Bathgate et al,86 1999 | 121 | 53 | In malnourished patients (TSF <fifth percentile) compared with well nourished, acute rejection occurred in 53% vs 35%; P = .97; comparing malnourished based on MAMC <fifth percentile to well nourished 15% vs 64% had acute rejection; P = .01 |

|

| |||

| Bilbao et al,3 2003 | 55 | 50 | Mortality rate of 46% for patients with liver resection and 36% for patients with liver transplant; Median survival was 85 mo in both groups, and 1-, 5-, and 10-y actuarial survival after LR and LT was 92% and 78%, 70% and 65%, and 50% and 60%, respectively (P = .8); Pretransplant renal insufficiency is the most significant risk factor for early mortality |

|

| |||

| de Carvalho et al,76 2010 | 70 | 69 | PCM was significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis compared with patients without cirrhosis at 90 d based on pretransplant PCM score (OR: 53.4, CI: 1.9–1481.9, P = .019) and 1 y after transplant based on TSF (OR: 7.202, CI: 1.2–44.1, P = .033) |

|

| |||

| Deschenes et al,87 1997 | 109 | 33 | 6-mo survival rates for patients classified as Child-Pugh A, B, C were 90%, 78%, and 65%; No 6-mo survival impact of nutritional status |

|

| |||

| Englesbe et al,17 2010 | 163 | 50 | Total psoas area had significant (P<.0001) effect on mortality after liver transplant with an adjusted HR = 0.27 (95% CI: 0.14–0.53) per 1000 mm2 increase in psoas area |

|

| |||

| Figueiredo et al,88 2000 | 53 | 9.4–39.6 | Comparing survivors and nonsurvivors, patients with longer ICU stay had lower HG on right (27 ± 6 and 36 ± 12 kg, P = .01) and left (27 ± 7 and 35 ± 12 kg, P = .01); lower lean body mass (51 ± 11 and 59 ± 14 kg, P = .05) |

| 43% of patients experienced 1 or more episode of biopsy-proven acute cellular rejection and had significantly lower BMI (26 ± 6 and 29 ± 5 kg/m2, P = .04) and lower total body fat (21 ± 8 and 30 ± 9 kg, P<.001) | |||

|

| |||

| Le Cornu et al,89 2000 | 82 | 53 | Malnutrition defined as MAMC <25th percentile, pretransplant nutritional status was not associated with survival; however, median survival in the group supplemented with caloriedense enteral feed vs control had 90% vs 50% 1-y survival |

|

| |||

| Merli et al,10 2010 | 38 | 53 | Estimated survival rate was 82.7% at 1 y, 65.1% at 3 y, and 50.7% at 5 y; MAMC <fifth percentile increased mortality risk based on relative risk = 1.79 |

|

| |||

| Montano-Loza et al,16 2011 | 112 | 40 | Only independent associations with mortality using multivariate Cox analysis were Child-Pugh (HR: 1.85; P = .04), MELD scores (HR: 1.08; P = .001), and sarcopenia (HR: 2.21; P = .008); Median survival time for patients with sarcopenia was 19 ± 6 mo compared with 34 ± 11 mo among patients without sarcopenic (P = .005) |

|

| |||

| Muller et al,90 1992 | 123 | 31 | Posttransplantation mortality was independent of pretransplantation REE, but it increased significantly in patients with losses in BCM |

|

| |||

| Selberg et al,5 1997 | 150 | 46 | Hypermetabolism as defined by ΔREE >20% and malnutrition defined by BCM <35% are present in significant proportion of patients awaiting liver transplant (20.4 ± 10% and 33.8 ± 6%). |

|

| |||

| Shahid et al,91 2005 | 61 | 30 | MAC and TSF were significantly associated with postoperative death (P = .04 and P = .02); No statistically significant correlation between the nutritional measures and probability of acute rejection |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HG, handgrip strength; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; LR, liver resection; LT, liver transplant; MAMC, midarm muscle circumference; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; OR, odds ratio; PCM, protein calorie malnutrition; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; REE, resting energy expenditure; TSF, triceps skinfold thickness.

Summary: The impact of malnutrition on survival in cirrhosis is described in these 13 studies (n = 1187). The prevalence of pretransplant malnutrition was between 9.4% and 69.0%. Malnutrition is defined by BIA, HG, TSF, SGA, and total psoas area. The presence of malnutrition increased morbidity and mortality, including acute rejection after transplant and prolonged ICU stay. There is a statistically significant correlation between the severity of malnutrition and mortality.

Malnutrition and Quality of Life

Quality of life in cirrhosis is significantly lower than that in controls (Table 3).6,93-98 This finding has been related to the severity of underlying liver disease as assessed by the Child’s scoring system. Because the Child’s score relates to the severity and prevalence of malnutrition, it is expected that malnutrition will be related to the quality of life. Recently, in a prospective study of 61 patients with cirrhosis, those with malnutrition as defined by SGA had impairment in 6 of the 8 quality-of-life scales on the SF-36.94 However, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, quality of life was not related to tumor mass or hepatocellular failure.95 Similarly in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, a condition with the most severe reduction in fat and muscle mass, the Nottingham health profile, a measure of quality of life, was not related to severity or duration of the disease.96 However, in neither of these studies was the relation between malnutrition and quality of life evaluated. In summary, based on existing data, patients with cirrhosis and malnutrition as assessed by SGA had a worse quality of life than those with preserved muscle and fat mass. These findings were independent of the complications of cirrhosis. More recently, previous episodes of HE, even after complete resolution, impact the quality of life in patients with cirrhosis.99 However, in a prospective study, minimal HE did not seem to have a significant impact on quality of life in patients with cirrhosis.98 This finding was in contrast to clinical expectations and recent interest on the impact of minimal HE on driving skills and motor vehicle–related accidents.100,101

Table 3.

Impact of malnutrition on quality of life in cirrhosis

| Author/Year | n | Definition of Malnutrition | Prevalence of Malnutrition (%) | Quality-of-life Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arguedas et al,97 2003 | 160 | Not assessed | Not assessed | Patients completed the SF-36, those with advanced cirrhosis Child-Pugh class B/C, had significantly lower PCS scores compared with patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis (P = .02); Patients with overt HE (grade I) had lower PCS scores compared with patients without HE (P = .018) |

|

| ||||

| Kalaitzakis et al,6 2006 | 128 | TSF, MAMC <10th percentile or BMI <20 kg m2 | 19 in non EtOH cirrhosis, 53 in EtOH cirrhosis | Controls vs patients with cirrhosis showed higher gastrointestinal symptom severity (total GSRS score: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.50–1.55 vs 2.21, 95% CI: 2.04–2.38) and profound reductions in the SF–36 physical (47.0 95% CI: 45–49 vs 37.9 95% CI: 35.7–40.1) and mental component summary scores (51.0 95% CI: 49.0–53.0 vs 39.2 95% CI: 36.7–41.6) |

|

| ||||

| Les et al,93 2010 | 212 | BMI | Not assessed | HRQOL scores (global CLDQ = 4.8 ± 1.17, PCS = 38.6 ± 10.7, MCS = 45.3 ± 14.3) showed a decrease with worsening of liver function; There is a significant correlation between the Child-Pugh classification and the different domains of the CLDQ and the SF-36 |

| MAMC | ||||

| HG | ||||

|

| ||||

| Norman et al,94 2006 | 200 | SGA A = well nourished | 48 | Malnourished vs well-nourished patients had decreased BMI (25.7 ± 4.6 vs 21.6 ± 4.2 kg/m2), decreased BCM/height (8.6 ± 1.7 vs 7.4 ± 1.8 kg/m2), decreased arm muscle area (4713.2 ± 1261.8 vs 3918 ± 1200.1) P<.000, decreased quality of life on chronic liver disease questionnaire, increased bodily pain (30% vs 40% P<.01), decreased social functioning 100% vs 70% P<.01), decreased mental health (70% vs 60% P<.01) |

| SGA B, C = malnourished | ||||

| Anthropometric | ||||

| Handgrip strength | ||||

|

| ||||

| Poon et al,95 2004 | 41 | Branched chain amino acid level | 59 | Patients with malnourished liver/ cirrhosis vs controls had decreased quality of life on FACT-G score 87 (65–98) vs 86 (74–99) at pretreatment and 89 (68–96) vs and 84 (70–96) P<.05; Patients transplanted for ALF or CLD had significantly worse HRQOL than the general population |

|

| ||||

| Poupon et al,96 2004 | 276 | Not assessed | Not assessed | Using the NHP to assess HRQOL, Patients with PBC showed a strong statistically significant difference in energy compared with controls (respectively, 40.6 vs 22.9, P<.0001) and had worse scores for emotional reactions (22.2 vs 16.1, P<.005) |

|

| ||||

| Wunsch et al,98 2011 | 87 | Not assessed | Not assessed | HRQOL was analyzed in patients without (n = 48) and patients with minimal HE (n = 29); Comparison of patients with vs without minimal HE, no differences in any of CLDQ and SF-36 domains |

Abbreviations: ALF, acute liver failure; BCM, body cell mass; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease; CLQD, chronic liver disease questionnaire; FACT-G, functional assessment of cancer therapy-general; GSRS, gastrointestinal symptoms severity score; HRQOL, health related quality of life; MAMC, midarm muscle circumference; NHP, Nottingham health profile; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; TSF, triceps skinfold thickness.

Summary: The impact of malnutrition on quality of life in cirrhosis is described in the previous 7 studies (n = 1104). Malnutrition is defined by BIA, MAMC, TSF, SGA, and branched chain amino acids levels. The prevalence of malnutrition ranged from 19% to 59%. Malnourished patients had statistically significant increase in gastrointestinal symptoms and decreased quality of life on the CLQD, SF-36, and NHP questionnaire.

Malnutrition and Clinical Complications of Cirrhosis

The known major life-threatening complications of cirrhosis that include ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding, HE and hepatorenal syndrome, and all of these are adversely affected by malnutrition and sarcopenia (Table 4).4,8,9,81,102-104 Other complications include hepatocellular carcinoma and pulmonary and cardiac complications of cirrhosis.105 Each of these complications aggravates the catabolic state by their impact on circulating cytokines and hormones and results in the reduction of muscle mass.35 However, few studies have systematically evaluated the impact of malnutrition on the development and progression of these complications. In a classical study by Moller,106 the development of portal hypertension, portosystemic collaterals, and varices were more severe and common in malnourished patients. In this study, nutritional status was scored by a subjective assessment scale of 1 to 4, with 4 being cachexia. Even though the investigators do not describe the validation process of this scoring system, this study demonstrates that malnourished patients had more severe portal hypertension and risk of variceal bleeding.

Table 4.

Impact of malnutrition on complications of liver disease in cirrhosis

| Author/Year | n | Definition of Malnutrition | Prevalence of Malnutrition (%) | Complications of Liver Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All complications | 50 | SGA | 28 | 65.5% of malnourished subjects vs 11.8% of well-nourished subjects developed uncontrolled ascites, HE, SBP, and hepatorenal syndrome when assessed by HG (P = .001); 33.3% of malnourished subjects developed these major complications vs 46.2% well-nourished subjects when assessed by PNI (P>.05); 35.7% of malnourished subjects developed these complications vs 44.4% well-nourished subjects when assessed by SGA (P>.05) |

| Alvares-da-Silva and Reverbel da,4 2005 | PNI | 19 | ||

| HG | 63 | |||

|

| ||||

| Huisman et al,8 2011 | 84 | HG | 67 | Malnourished patients vs well-nourished patients had (48% vs 18%, P = .007) complications at follow-up, new-onset ascites (27% vs 18%, P = .365), HE (29% vs 0%, P = .00), hepatorenal (13% vs 0%, P = .051), SBP (14% vs 0%, P = .035); |

| MAMC | 58 | In univariate analysis using logistic regression, malnutrition measured with HG (OR: 4.3; CI: 1.4–12.9), P<.2 when comparing patients with and without complications during follow-up | ||

| SGA | 58 | |||

| BCM | 39 | |||

| BMI | 5 | |||

|

| ||||

| SBP | 38 | SGA | 53 | 73% of malnourished patients assessed by SGA had 1 or more infections; |

| Merli et al,9 2010 | MAMC | Total number of infective episodes per patient was significantly higher in malnourished patients compared with patients with no malnutrition, P<.000001; | ||

| Total number of days in the ICU was influenced only by malnutrition (SGA A-B, C) HR 0.18; P = .0003 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Portal HTN | 114,703 | Clinical diagnosis | 6.1 | PCM was higher among patients with cirrhosis and PHTN compared with general medical inpatients (6.1% vs 1.9%, P<.0001; OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.4–1.7) |

| Sam and Nguyen,81 2009 | In patients with cirrhosis and PHTN, significantly higher rates of malnutrition in patients with alcohol abuse compared with those without (7.6% vs 4.7%, P<.0001), greater prevalence of ascites (64.6% vs 47.9%, P<.0001), and hepatorenal syndrome (5.1% vs 2.8% P<.0001) but not HE (60.8% vs 59.7%, P = .11) among patients with malnutrition and cirrhosis with PHTN | |||

|

| ||||

| Montomoli et al,102 2010 | 21 | BIA | 30 | TIPS procedure lowered portal pressure before compared with after (6.0 ± 2.1 mm Hg vs 15.8 ± 4.8 mm Hg, P<.001). After TIPS, normal-weight patients had an increase in dry lean mass (from 10.9 ± 5.9 kg to 12.7 ± 5.6 kg, P = .031) and TBW (from 34.5 ± 7.6 L to 40.2 ± 10.8 L, P = .007) |

|

| ||||

| HE | 128 | Anthropometry, MAC <fifth percentile | 40 | Patients with vs without malnutrition had more frequent episodes of HE (46% vs 27%; P = .031); There was no difference in episodes of HE comparing alcohol cause of liver disease vs other cause (49% vs 37%, P = .202), severity of cirrhosis by CP score (2.5% vs 2.2%, P = .09) or by MELD (6% vs 5%, P = .275) |

| Kalaitzakis et al,7 2007 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ndraha et al,104 2011 | 34 | Prealbumin level | 50 | Malnourished patients randomized into groups received LOLA (group A) vs without LOLA (group B); CFF value in group A (2.41 ± 1.6 Hz) compared with group B (0.67 ± 2.3 Hz) P = .016; |

| Increased incidence of minimal HE in patients with low MAMC; Minimal HE with malnutrition can be improved by use of L-ornithine-L-aspartate | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ascites | 396 | MAMC, BMI, TSF <5th or 10th percentile | 39 | Prevalence of severe malnutrition highest in TAP (39.1%); Comparing TAP vs NAP, MAMC <5th or 10th percentile (65.5% vs 51.0%) and TSF <5th or 10th percentile (49.4% vs 30.4%) with P<.0001; |

| Campillo et al,192 2003 | In multivariate analysis, patients with TSF <5th or 10th percentile were positively associated with tense ascites (OR: 2.833, CI 95: 1.603–5.014, P = .0004) | |||

Abbreviations: BCM, body cell mass; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CP, Child Pugh; HG, handgrip strength; LOLA, L-ornithine-L-aspartate; MAMC, midarm muscle circumference; MELD, model end-stage liver disease; NAP, nonascitic patients with cirrhosis; OR, odds ratio; PCM, protein calorie malnutrition; PHTN, portal hypertension; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; TAP, patients with cirrhosis with tense ascites; TBW, total body water; TSF, triceps skinfold.

Summary: Seven studies (n = 751) describe the impact of malnutrition on the complications of liver disease. Malnutrition is defined by BMI, HG, MAMC, TSF, and SGA. Prevalence of malnutrition is 6.1% to 67.0%. Complications of liver disease included are ascites, SBP, portal hypertension, hepatorenal syndrome, and HE. There is a statistically significant increase in complications in patients with malnutrition.

In states of hepatocellular dysfunction and portal hypertension, plasma concentration of ammonia is elevated, and the skeletal muscle has been suggested to play a significant role in ammonia detoxification.42,107 Because hyperammonemia is considered to be the major pathogenic factor in the development of HE, it has been speculated that low muscle mass will predispose to and aggravate the severity of HE. There are 2 studies that have specifically examined the impact of malnutrition on the development and outcome of HE with conflicting results.7,108,109

Both of these are single time-point cross-sectional assessments for malnutrition as defined by anthropometric and other criteria. In the study by Kalaitzakis and colleagues7 in 128 patients with cirrhosis of varied causes, HE was diagnosed as overt by West Haven criteria and the number connection test. Malnutrition was defined by anthropometric measurement less than the fifth percentile of established norms for the general population, body mass index less than 20 mg/m2, or weight loss of greater than or equal to 5% to 10% in the previous 3 to 6 months. Among these patients, 40% had malnutrition and 34% had HE. Patients with malnutrition had HE more frequently, and malnutrition was an independent risk factor for HE. In contrast, in another prospective study by Soros and colleagues,108 nutritional assessment was performed using body mass index, anthropometrics using the triceps skinfold thickness and arm muscle area, and bioelectrical impedance. It is interesting that the 2 studies yielded conflicting results in terms of the impact of malnutrition on the development of HE. Unfortunately, both were cross-sectional studies and did not specifically examine the impact of sarcopenia on the development of HE. One of the major confounding factors in these assessments is that previous episodes of HE are also likely to worsen sarcopenia by a combination of hyperammonemia, poor oral intake, and hospitalizations. In a prospective study, the authors demonstrated that the frequency of HE was higher in patients who had evidence of sarcopenia.110 The authors’ studies in an animal model of hyperammonemia (portacaval anastomosis [PCA] rat) and in murine myoblasts have suggested that ammonia induces the expression of myostatin, a transforming growth factor (TGF) β superfamily member that is known to worsen sarcopenia.111,112 The authors’ data suggest that hyperammonemia of cirrhosis induces HE and worsens sarcopenia. The development and progression of sarcopenia then begins a self-destructive cycle of recurrent HE and further loss of muscle mass caused by impaired nonhepatic ammonia disposal.

PATHOGENESIS AND MECHANISMS OF SARCOPENIA IN CIRRHOSIS

Because sarcopenia is the major contributor to malnutrition, functional status, and outcomes in cirrhosis, an understanding of the biochemical and cellular mechanisms that result in loss of muscle mass is critical to identify therapeutic targets. Initial works in understanding the metabolic alterations in cirrhosis were based on isotopic tracer methodology.113 Despite initial enthusiasm, these were predominantly descriptive studies; and only recently, the advances in myology, gerontology, and molecular biology are being translated into identifying precise molecular abnormalities in the skeletal muscle and their dysregulation in cirrhosis.15,114

Maintenance of Skeletal Muscle Mass

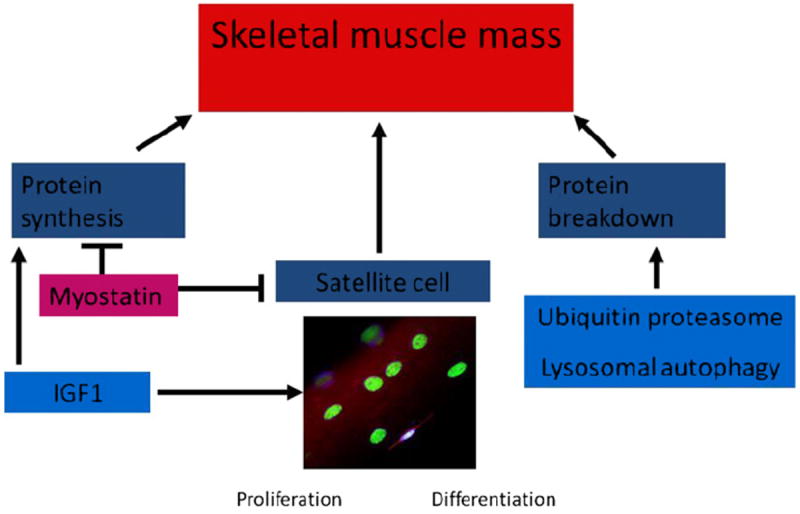

To understand the mechanisms of sarcopenia, an understanding of the mechanisms of maintenance of muscle mass is necessary (Fig. 1). Skeletal muscle mass is maintained by a balance between muscle protein synthesis, protein breakdown, and satellite cell proliferation and differentiation.115 Satellite cells are myogenically committed precursor cells that contribute nuclei to the myocytes for maintenance and growth of mature skeletal muscle.116,117 Increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis and satellite cell proliferation and differentiation are necessary for skeletal muscle growth.115 Satellite cells constitute 2% to 4% of adult skeletal muscle, whereas skeletal muscle structural protein is the major contributor to skeletal muscle mass. Therefore, alterations in skeletal muscle mass are primarily caused by changes in the structural protein content. Another critical concept that needs to be reiterated is that even though both impaired protein synthesis and increased protein breakdown contribute to the reduced muscle mass in cirrhosis, their contributions are distinct. A reduction in protein synthesis alone results only in the failure to accrete protein mass, whereas an increase in proteolysis is necessary for the loss of muscle mass. However, continued enhanced proteolysis precludes cell survival and needs to be regulated. Because protein synthesis and proteolysis do not occur independently, rather are highly integrated, it is the relative contribution that determines the muscle mass. Current methods to quantify skeletal muscle protein synthesis and proteolysis lack sufficient sensitivity to identify the small changes that occur with the disease.118 These methods are being supplemented by quantifying whole muscle protein synthesis instead of the traditional fractional synthesis rate in animal studies36,119 but have not been developed in humans yet. Furthermore, there are no studies that have directly quantified skeletal muscle protein synthesis or breakdown in human cirrhosis. The use of isotopic tracers using stable isotope-labeled amino acids have examined whole body protein metabolism in cirrhosis.1

Fig. 1.

Regulation of skeletal muscle mass. The protein synthesis and satellite cell (myogenically committed stem cells) contribute to muscle growth and reversal of atrophy. These are regulated primarily by myostatin and IGF1. The proteolysis is mediated primarily by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway with a variable contribution by the lysosomal cathepsin mediated autophagy pathway.

Protein Metabolism in Cirrhosis with Portosystemic Shunting

Protein turnover studies in cirrhosis using tracer isotopes have yielded conflicting results.120-123 These differences may be related to confounding variables, such as differences in disease severity, nutritional status, and the methodology used to quantify protein turnover. The estimation of rates of whole body protein breakdown using [1-13C]leucine, in humans with stable cirrhosis (defined as Child’s class A or B) in the fasted state, were not different from those in healthy controls.120 Studies using phenylalanine tracer showed a decreased whole body protein breakdown in patients with cirrhosis of Child’s class B and C (decompensated) and no difference between compensated patients with cirrhosis (Child’s class A and B) and healthy controls.124,125 Contradictory results have been reported using different isotopic tracers, such as [15N] glycine and [14C] tyrosine.126

Several methods have been used to examine protein synthesis in vivo.127 However, muscle biopsies are required for precise quantification of skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Even though these have not been reported in human patients with cirrhosis, whole body amino acid kinetic studies showed lower rates of protein synthesis in patients with cirrhosis than in controls.121,123 Arteriovenous differences in amino acid concentration in the lower extremity showed that proteolysis and protein synthesis were lower.123 These abnormalities may persist or worsen in the postprandial state in patients with cirrhosis.121

Data from studies in animal models are equally conflicting. In the rat model of carbon tetrachloride–induced cirrhosis, lower rate of protein breakdown and lower protein synthesis was observed.128 In the PCA rat, a lower rate of liver and brain protein synthesis was reported 3 weeks after anastamosis.129 In contrast, another study in PCA rats showed no difference in the rate of protein synthesis in different organs.130 An increased skeletal muscle proteolysis mediated by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway has been described in the bile duct ligated rat.131 However, the bile duct ligated rat as a model of cirrhosis differs from human cirrhosis because secondary biliary cirrhosis in humans is extremely rare and steatorrhea and malabsorption that accompany this procedure affect the muscle mass independent of cirrhosis.

Another pathway of protein breakdown that is being increasingly examined is the lysosomal cathepsin–mediated autophagy.132,133 Autophagy serves to remove long-lived and abnormal proteins and dysfunctional organelles and helps recycle the substrates generated to permit protein synthesis. Autophagy is enhanced during states of nutrient deprivation and cellular stress. Preliminary studies from the authors’ laboratory have shown an increased skeletal muscle autophagy. However, with the impaired muscle protein synthesis in cirrhosis, autophagy may be futile and contributes to sarcopenia, especially in the presence of reduced ubiquitin-proteasome–mediated proteolysis.

Despite the heterogeneity in the disease and methodologies used, the preponderance of evidence based on studies in humans and animals suggest an unchanged rate of protein breakdown and a decrease in the rate of protein synthesis in cirrhosis.113,121,123 Several confounding variables may have contributed to the differences in observations and include the stage of the disease at the time of study, underlying cause of cirrhosis, duration of illness, muscle mass before disease development, and comorbid conditions that also contribute to whole body and skeletal muscle protein metabolism.

Satellite Cells and Skeletal Muscle Mass

Skeletal muscle fibers in adults are composed of terminally differentiated myocytes that do not replicate.116,117 Their growth and adaptation to injury depend on a small population of stem cells called satellite cells that are committed to a myogenic lineage and are closely associated with the periphery of the muscle fibers.117 Proliferation and differentiation of satellite cells contribute to the accretion of myonuclei in mature muscle cells and growth of skeletal muscle.117,134 Impaired satellite cell proliferation and differentiation occur in sarcopenia of aging, calorie restriction, hind limb unloading, and immobilization.135-137 However, the contribution of impaired satellite cell function to the diminished muscle mass in cirrhosis is unknown. The authors have shown in the PCA rat an impaired satellite cell proliferation and differentiation as evidenced by the low expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and myogenic regulatory factors (myoD, myf5, and myogenin).38,39 The authors’ in vivo immunohistochemical studies using 5 bromo 2’ deoxyuridine incorporation have also shown that following PCA, there is a significantly lower mitotic index of satellitel cells compared with the control animals. These data suggest that satellite cell function is impaired in portosystemic shunting and may play a role in sarcopenia of cirrhosis. The enhancement of satellite cell function is a potential therapeutic target in these patients.

Molecular Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Protein Metabolism and Satellite Cell Function

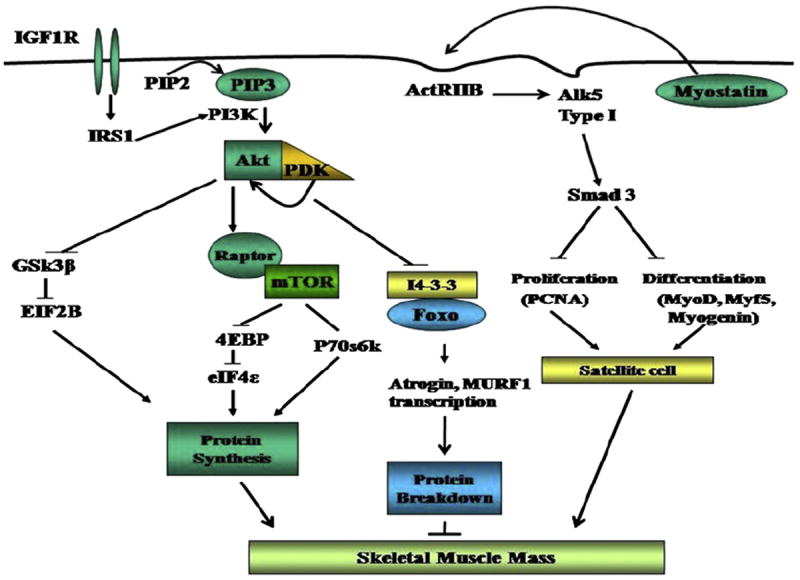

There are 2 regulatory pathways that contribute to skeletal muscle growth: (1) enhanced protein synthesis in existing muscle fibers and (2) proliferation and differentiation of myogenic satellite cells that fuse with the exiting muscle fibers (Fig. 2). Myostatin and IGF1 are the 2 major upstream regulators of these functions in the skeletal muscle. An increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis results from the activation of components of the highly regulated components of the canonical IGF1/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway (see Fig. 1).115 Activation of Akt and mTOR by phosphorylation results in the stimulation of ribosomal protein translation by the effector proteins, p70s6k and 4E-BP.138 The impairment of component proteins in this pathway results in reduced protein synthesis.115,139 Proteolysis that is responsible for the reduction in muscle mass is also regulated by myostatin and IGF1. Impaired phosphorylation and activation of Akt results in increased ubiquitin proteasome–mediated proteolysis, and reduced mTOR activation results in enhanced autophagy.34,140 These results demonstrate the complex crosstalk at different components between the critical regulators of muscle mass and their ultimate targets and functional consequences.

Fig. 2.

Integration of the 3 major pathways that regulate skeletal muscle mass. Myostatin and IGF1 regulate muscle growth via transcriptional and posttranslational regulation of myogenic genes. The ubiquitin proteasome pathway is responsible for proteolysis. All 3 pathways crosstalk at multiple levels, including Akt, mTOR, AMP kinase, and FOXO. PIP2, phosphatidyl inositor bisphosphate; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 3 phosphate; IGF1R, IGF1 receptor; Alk5, activinlike kinase 5, forms a heterodimeric complex with generic TGFβ receptor for myostatin; Act IIbr, activin II b receptor; GSK, 3β glycogen synthase kinase; eIF, eukaryotic initiation factor; 4E BP1, 4 E binding protein 1; IRS 1, insulin receptor substrate that is downstream of both insulin and IGF1 receptor; MURf, muscle ring finger protein, final component in the ubiquitin proteasome pathway with atrogin; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, a marker of satellite cell proliferation.

Myostatin, a member of the TGF β superfamily expressed in the skeletal muscle, is a potent inhibitor of muscle protein synthesis and satellite cell function.141 The authors have shown that the PCA rat is an appropriate model to examine the mechanisms responsible for failure to increase lean body weight and gain skeletal muscle mass with portosystemic shunting in cirrhosis.40,111 The authors have previously reported that an increased expression of myostatin occurred 2 weeks after PCA and accompanied the failure to gain skeletal muscle mass and impaired satellite cell function.38,39 This finding was accompanied by an impaired skeletal muscle protein synthetic response and decreased phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream targets, p70s6 kinase and 4 E binding protein 1.139 Others have shown that myostatin blocks an upstream regulator or mTOR (ie, protein kinase B or Akt.)142,143 The administration of follistatin reversed the myostatin-induced loss of lean body mass, skeletal muscle weight, and impaired phosphorylation of mTOR and p70s6k.36 Myostatin has also been shown to activate the ubiquitin proteasome–mediated proteolysis and the lysosomal autophagy.140,144

IGF1

In addition to myostatin, IGF1 is the other major factor that regulates skeletal muscle protein metabolism.34 There is some evidence that locally produced IGF1 in the skeletal muscle (mechano-growth factor) mediates these effects rather than the circulating.145 IGF1 increases muscle mass by promoting protein synthesis, inhibiting protein breakdown, and increasing satellite cell proliferation and differentiation. The intracellular signaling pathways downstream of IGF1 binding to its receptor, IGF1 receptor α (IGF1R α) have been well characterized.115 Increased skeletal muscle protein synthesis and satellite cell proliferation in response to IGF1 are mediated by the activating Akt and sequential phosphorylation and activation of its downstream targets.146,147 These data suggest that Akt is the central mediator of critical components of the pathway of protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle.

There is intense interest in the regulation of skeletal muscle IGF1 and myostatin in liver disease. Identification of the binding sites of both androgen receptor and nuclear factor kB on the promoter region of myostatin also holds promise as effective therapeutic targets. Translation of these data from animal and in vitro cell culture studies to humans is essential.

AGING PATIENTS WITH CIRRHOSIS

As the global population ages, this contributes to the progressive worsening of sarcopenia. It is estimated that after the age of 50 years, approximately 1% of skeletal muscle loss occurs per year.148,149 The impact and interaction of sarcopenia of aging and cirrhosis are not known. The adverse effects of both of these processes on muscle mass and function may be exponential, contributing to an urgent need to increase our understanding of the mechanisms and identification of therapies.

POSTTRANSPLANTED PATIENTS WITH CIRRHOSIS

Pretransplant malnutrition, specifically sarcopenia, adversely impacts the perioperative and immediate posttransplant outcomes (Table 5). Additionally, pretransplant sarcopenia is associated with worse outcomes after liver transplantation.5,17 It is thought that liver transplantation is curative for cirrhosis. However, it must be reiterated that this option is available only to a minority of patients. Furthermore, posttransplant metabolic syndrome and the attendant insulin resistance adds to the worsening of muscle loss.150,151 Finally, mTOR inhibitors, calcineurin inhibitors, and corticosteroids, commonly used immunosuppressants used after transplantation, alter the expression and activity of critical regulators of muscle protein metabolism.152-154 These observations support the urgent need to develop therapies to reverse and treat sarcopenia in cirrhosis because this casts a long shadow from before transplantation to after the procedure.

Table 5.

Impact of malnutrition on liver transplant outcomes in cirrhosis

| Author/Year | n | Definition of Malnutrition | Prevalence of Malnutrition (%) | Liver-Transplant Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Carvalho et al,76 2010 | 70 | Anthropometry; BIA | 69 pretransplant; 63 posttransplant | Pretransplant 44.3% of patients had mild PCM and 24.3% had moderate or severe PCM; Univariate analysis of all patients at 90 d showed cirrhotic vs noncirrhotic (53.6 × 100% malnourished, X2 = 8.5, P = .004) as an important factor associated with PCM; PCM was significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis compared with patients without cirrhosis at 90 d based on pretransplant PCM score (OR: 53.4, CI: 1.9–1481.9, P = .019) and 1 y after transplant based on TSF (OR: 7.202, CI: 1.2–44.1, P = .033) |

|

| ||||

| Englesbe et al,17 2010 | 163 | TPA | 50 | TPA had a significant (P<.0001) effect on mortality after liver transplant with an adjusted HR = 0.27 (95% CI: 0.14–0.53) per 1000 mm2 increase in psoas area; 1-y survival ranged from 49.7% for small TPA vs 87.0% with large TPA |

|

| ||||

| Figueiredo et al,88 2000 | 53 | Anthropometry SGA | 9.4–39.6 | Comparing survivors and nonsurvivors, patients with longer ICU stay had lower handgrip strength on right (27 ± 6 and 36 ± 12 kg, P = .01) and left (27 ± 7 and 35 ± 12 kg, P = .01); lower lean body mass (51 ± 11 and 59 ± 14 kg, P = .05) |

| Handgrip strength BCM | 43% of patients experienced 1 or more episode of biopsy-proven acute cellular rejection and had significantly lower BMI (26 ± 6 and 29 ± 5 kg/m2, P = .04) and lower total body fat (21 ± 8 and 30 ± 9 kg, P<.001) | |||

|

| ||||

| Harrison et al,190 1997 | 102 | MAMC <25th percentile | 28 | Malnourished patients defined by MAMC <25th percentile have increased risk of infection compared with controls (66% vs 52%), increased susceptibility, decreased graft function (2 malnourished patients had primary nonfunction of their hepatic allograft); Malnourished patients had statistically significant difference in 6-mo postoperative mortality but not statistically significant (Wilcoxon-Gehan statistic, 199, P = .09); |

| TSF | In multiple regression analysis with percentile position for MAMC as the dependent variable, significant relations were seen for age (beta = −0.15, T = −2.0, P = .05), and survival (beta = −0.18, T = −2.5, P = .01) | |||

|

| ||||

| Merli et al,10 2010 | 38 | Anthropometry, SGA | 53 | Pretransplant nutritional status was associated with number of episodes of infections and length of stay in ICU because 73% of malnourished patients assessed by SGA had 1 or more infections; |

| Total number of infective episodes per patient was significantly higher in malnourished patients compared with patients with no malnutrition (85 vs 11) P<.000001; Total number of days in the ICU was influenced only be malnutrition (SGA A-B, C) HR: 0.18; P = .0003 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Pikul et al,56 1994 | 69 | SGA | 79 | Patients were categorized by SGA: 19% mild, 34% moderate, and 26% severely malnourished; Significant increase in number of days requiring ventilator support comparing mild vs severe (8 ± 10 vs 41 ± 37 d), hospital days (33 ± 13 vs 82 ± 40 d), and higher incidence of tracheostomy (15% vs 67%) |

|

| ||||

| Selberg et al,5 1997 | 150 | Anthropometry, BCM <35% | 50 | Hypermetabolism as defined by ΔREE >20% and malnutrition defined by BCM <35% are present in significant proportion of patients awaiting liver transplant (20.4 ± 10% and 33.8 ± 6%) and correlate with survival after transplant; Comparing survival in patients with hypermetabolism and malnutrition vs controls is 60% vs 90% |

| BIA | ||||

|

| ||||

| Stephenson et al,191 2001 | 109 | SGA | 32–35 | Using nutritional status as a lone preoperative variable using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, patients with severe malnutrition required more blood products intraoperatively comparing severely malnourished vs moderate (5.5 ± 5.5 vs 3.0 ± 6, P = .026; vs mild 1.5 ± 3, P<.0001); These patients had longer hospital stay, severe vs moderate (16 ± 9 vs 10 ± 5 d, P = .0027; vs mild 9 ± 8 d, P = .0006) |

| First study to show that malnutrition was independent predictor of intraoperative transfusion requirements during OLT independent of UNOS status | ||||

Abbreviations: BCM, body cell mass; BIA, bioelectric impedance; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; MAMC, midarm muscle circumference; OLT, orthotopic liver transplant; PCM, protein calorie malnutrition; REE, resting energy expenditure; TPA, total psoas area; TSF, triceps skinfold; UNOS, united network of organ sharing.

Summary: Eight studies (n = 754) assessed the impact of malnutrition on liver-transplant outcomes. Prevalence of malnutrition ranged form 9.4% to 79%. Malnutrition was defined by BIA, HG, MAMC, TSF, and SGA. Severe malnutrition independently predicted intraoperative complications, increased episodes of infection, increased length of stay in the ICU, acute cellular rejection, and increased transfusion requirements.

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Given the human data that suggest that cirrhosis is a state of accelerated starvation,155 several nutrient interventions have been tried with limited success in long-term improvement in protein or energy metabolism.156,157 Several hormonal alterations have resulted in interventions that use anabolic androgens, IGF, and growth hormone with no benefit and several adverse effects.158-161 Current studies underway on understanding the mechanisms of alteration in protein and fat malnutrition in cirrhosis are likely to provide the basis of novel treatment options (Table 6). Methods to determine the nutritional needs have also been devised and include quantification of the resting energy expenditure (REE), respiratory quotient (RQ), and daily protein needs.

Table 6.

Therapeutic options for malnutrition in cirrhosis

| Author/Year | n | Definition of Malnutrition | Prevalence of Malnutrition (%) | Therapeutic Intervention | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campillo et al,103 1997 | 55 | MAMC <fifth percentile | 73 | Oral nutrition | Patients with cirrhosis were given oral nutrition with caloric intake of ~40 kcal/kg of BW, this study compared Child A, B, C classification. FM increased from 17.4% ± 1.7%–19.5% ± 1.4%, P<.01, in Child A patients; from 17.1% ± 1.4%–19.3% ± 1.4%, P<.001, in Child B patients; and from 17.6% ± 1.5%–18.8% ± 1.5%, P<.05, in Child C patients, all categories received oral nutrition; Increase in FM was comparable in 3 groups, no significant increase in MAMC, TSF, or creatinine/height ratio |

| TSF <25th percentile | 51 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Kondrup et al,165 1997 | 11 | BW <80% of reference weight, or LBM <80% of reference value LBM was calculated from three 24-h urinary | 57 | Oral nutrition, high-protein diet | Patients were initially in energy balance (intake 7.9 ± 0.7) MJ per day vs energy expenditure (7.5 ± 0.3) MJ per day; During refeeding, energy intake was increased in proportion to protein intake; Malnourished patients with cirrhosis have both high protein use and require increased amount of protein to achieve nitrogen balance because of an increase in protein degradation; It is speculated that this is caused by low levels of IGF-I secondary to impaired liver function because initial plasma concentration of IGF-I was about 25% of control values and remained low during refeeding |

| creatinine excretions | |||||

|

| |||||

| Nielsen et al,168 1995 | 15 | BW <80% of reference weight, or LBM <80% of reference value; LBM was calculated from three 24-h urinary | 63 | Oral nutrition | Malnourished patients with EtOH cirrhosis were given increasing amounts of a balanced ordinary diet for 38 ± 3 d; Total nitrogen disposal was calculated after measurement of urinary and fecal nitrogen loss; Initial protein balance noted to be 0.50 ± 0.17 g/kg/d in malnourished patients with cirrhosis; Refeeding resulted in doubled protein intake from 0.98 ± 0.08 vs 1.78 ± 0.11 g/kg/d; increased anthropometric values, LBM (72-h creatinine) 2.4 ± 0.6 kg (P<.005); MAMA 3.1 ± 0.5 cm2 (P<.001) and TSF 0.7 ± 0.3 mm (P<.05) |

| creatinine excretions | |||||

|

| |||||

| Plauth et al,169 2000 | 16 | Serum ammonia and glutamine level | Not assessed | Enteral nutrition vs parenteral nutrition | Using TIPS to examine mesenteric venous blood, both glutamine and ammonia concentrations were measured in patients with cirrhosis; Patients that were given enteral nutrient infusion, ammonia release increased rapidly compared with postabsorptive state 65 (58–73) vs 107 (95–119) μmol/l after 15 min (95% CI) compared with parenteral infusion 50 (41–59) vs 62 (47–77) μmol/l; There was a higher blood ammonia: 14 (11–17) vs 9 (6–12) μmol/l in enteral compared with parenteral nutrition; These data indicate small intestinal metabolism contributes to hyperammonemia, therefore, parenteral nutrition is superior to enteral |

|

| |||||

| Swart et al,170 1989 | 8 | BCAA level | 50 | Oral nutrition, 40-g protein diet | Comparing the effect of nitrogen balance on BCAA protein and natural protein, patients were in a negative nitrogen balance on a 40-g protein diet (−0.75 ± 0.15 gN) and in positive nitrogen balance on 60 g (+1.23 ± 0.22 gN) or 80 g of protein per day (+2.77 ± 0.20 gN); Patients with higher nitrogen balance had improved physical condition, mean minimum protein requirement (48 ± 5 g of protein per day or 0.75 g/kg/d), and decreased episodes of HE |

|

| |||||

| Vaisman et al,171 2010 | 21 | Serum ammonia level >85 μg/dl | Not assessed | Oral nutrition, 4–7 meals per day | Patients with cirrhosis with levels of ammonia >85 μg/dl scored significantly lower global cognitive score 92 ± 10.6 vs 100 ± 5.9 (P<.015) in healthy controls. PCM is prevalent in all clinical stages of liver disease. In patients with cirrhosis, attention (3.6 ± 10.6 vs 4.09 ± 2.93) and executive function (6.38 ± 9.06 vs −0.63 ± 4.11) increased with breakfast compared with without breakfast (P =.04) |

Abbreviations: BCAA, branched chain amino acid; BW, body weight; EtOH cirrhosis, alcoholic cirrhosis; FM, fat mass; LBM, lean body mass; MAMA, midarm muscle area; MAMC, midarm muscle circumference; MJ, megajoule; PCM, protein calorie malnutrition; TSF, triceps skinfold.

Summary: Six studies (n = 126) describe the therapeutic interventions for malnutrition in cirrhosis. Malnutrition is defined by BCAA, BW, LBM, MAMC, serum ammonia and glutamine level, and TSF. Prevalence of malnutrition is 50% to 73% and was not assessed in 2 studies. Therapeutic options include modified eating patterns with increased protein through either oral nutrition or parenteral. Malnourished patients are noted to have increase in other complications of cirrhosis, including ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, portal hypertension, hepatorenal syndrome, and HE. There is a statistically significant increase in LBM and FM in patients with cirrhosis with improved oral or parenteral nutrition.

The standard method to measure REE and RQ is the use of a metabolic cart. However, cost, logistics, and complexity of the test have led to this being used only in research settings. Interest has increased recently in the use of a handheld calorimeter that has been found to be more precise than a variety of predictive equations. In hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, the authors have found the handheld respiratory calorimeter (MedGem, Microlife Medical Home Solutions, Inc., CO, USA) to be as precise as a metabolic cart in the clinical research unit in quantifying REE. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines suggest no protein restriction in patients with cirrhosis based on published studies.157

NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTATION

Because skeletal muscle is the major whole body protein store, with a reduction in muscle mass, whole body protein content is lower. Increased protein intake has been demonstrated to be safe, well tolerated, and beneficial in patients with cirrhosis, but the long-term anabolic effects on muscle mass and function have not yet been established.33,156,162-166 Several nutritional interventions have been examined that have focused on 2 specific areas: decrease the intermeal frequency and increase caloric and protein intake (Table 7).93,103,167-171 However, as stated earlier, recent advances in our understanding of skeletal muscle biology, regulatory pathways, and targeted interventions have not been evaluated. Separation of adipocyte and skeletal muscle responses to specific interventions are likely to result in the reversal of sarcopenia without the accompanying increase in fat mass and to avoid the development of sarcopenic obesity.

Table 7.

Pathophysiology-based therapeutic options

| Mechanism | Therapy | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperammonemia | Lactulose, rifaximin | Not assessed |

| Low branched chain amino acids | Replace with BCAA | Partial response |

| Low leucine | Leucine-enriched essential amino acids | Not evaluated |

| Increased gluconeogenesis, accelerated starvation | Late-evening snack | Partially effective |

| Low IGF | IGF1, growth hormone | Not effective |

| Low androgens | Testosterone, oxandrolone | Partially effective |

| Increased myostatin | Myostatin antagonists | Not studied |

| Decreased physical activity | Aerobic and resistance exercise | Not effective, risk of variceal bleeding |

| Portal hypertension | TIPS | Improves muscle size and lean body mass |

Abbreviation: BCAA, branched chain amino acid.

Dietary modification and supplements have been examined with conflicting results. Frequent snacks, late-evening snacks, branched chain amino acid supplementation, breakfast, and protein supplementation have been examined with beneficial results but have not been incorporated into routine clinical practice.22,171-173 There is increasing evidence that shortening the interval between meals will reduce the severity and prevalence of malnutrition in cirrhosis.22 Hence, the emphasis has been on late-evening snacks and, recently, on breakfast on waking up.22,171 Both these measures have the benefit of increasing the availability of amino acids and suppressing gluconeogenesis from amino acids derived from endogenous proteolysis. Furthermore, both splanchnic and whole body protein breakdown are suppressed by dietary intake. Late-evening snacks have been shown to improve whole body protein kinetics with lower protein breakdown and increased protein synthesis. However, these are short-term effects. Animal data in the portacaval shunted rat model suggest that early in the course of the illness, there is increased proteolysis; and later, once loss of muscle and fat mass is established, there is an impaired skeletal muscle protein synthesis.39 This interpretation is supported by studies in stable patients with cirrhosis in whom there is increased whole body protein breakdown.33 The stage of the disease and underlying cause affect the severity of malnutrition in humans. However, the authors’ animal data suggest that the duration of illness plays a significant role, with increased proteolysis early and impaired protein synthesis late in the disease.36 Therefore, the therapeutic strategy will be to focus on reducing muscle proteolysis early in the disease and promote muscle protein synthesis later in the disease once muscle loss is established. Furthermore, the authors’ observation of increased skeletal muscle autophagy is novel and needs further studies for its implications in the pathogenesis and reversal of sarcopenia in cirrhosis.

Of the essential amino acids, leucine holds the most promise as an intervention to reverse sarcopenia in aging.174,175 Leucine is not only an essential amino acid substrate for protein synthesis but also functions as a direct activator of the critical protein synthesis and autophagy regulator, mTOR.176 Additionally, leucine stimulates insulin release from the pancreatic β cells that functions as an anabolic hormone in the skeletal muscle.177 Finally, leucine is an energy substrate in the skeletal muscle. However, because the administration of leucine will stimulate muscle protein synthesis, other essential amino acids may become limiting and need to be replaced.178 Leucine-enriched essential amino acids can, therefore, be considered in the long-term management of sarcopenia of cirrhosis. It has been identified that reversing sarcopenia and cachexia can improve outcome in other disorders, like cancer.179 A similar therapeutic approach in patients with cirrhosis is likely to improve survival, quality of life, and the development of other complications. Such outcome measures have not yet been reported. The authors recently showed that in response to TIPS, a subgroup of patients had an improvement in muscle size measured on CT. These patients had significantly better survival compared with those who either did not increase or had a reduction in muscle size.92

Micronutrient Replacement

Even though the authors have not focused on micronutrient replacement in cirrhosis, deficiency of vitamin D and zinc are well recognized and need to be identified and treated.180-184

Exercise

The role of aerobic and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle insulin signaling, protein synthesis response, AMP kinase activity, and satellite cell function has been studied extensively in aging.185,186 However, fatigue; reduced maximum exercise capacity in patients with cirrhosis; and the presence of limiting complications, including ascites, encephalopathy, and portal hypertension, have limited the translation of the data or the elegant designs of the studies performed in patients without cirrhosis.187 Resistance exercise increases portal hypertension, and even transient increases in portal hypertension can result in catastrophic variceal bleeding and death.188 It is, therefore, critical that the data on the impact of exercise on muscle mass and function be translated very judiciously in patients with cirrhosis.

Novel strategies to reverse cachexia, including myostatin antagonists, are also of clinical interest, especially given recent data that myostatin may play a critical role in cirrhotic sarcopenia.35,189 The authors’ data in an animal model that the adverse consequences of increased myostatin expression can be reversed without impacting the underlying liver disease are especially exciting36 because liver transplantation is not a universally available treatment option and reversing hepatic cachexia-sarcopenia should be a major therapeutic option for cirrhosis. Given the paucity of data, the understudied nature of the problem, sarcopenia in cirrhosis deserves to be recognized as an area of unmet need with the potential to improve the outcome of the large number of patients with cirrhosis. One potential strategy for the development of novel and successful therapies is the need for consilience between the diverse and seemingly unrelated fields of aging, molecular signaling, nutraceuticals, hepatology, transplant immunology, clinical nutrition, and transplant surgeons.

References

- 1.Tessari P. Protein metabolism in liver cirrhosis: from albumin to muscle myofibrils. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6(1):79–85. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi G, Marzocchi R, Agostini F, et al. Update on nutritional supplementation with branched-chain amino acids. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8(1):83–7. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200501000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilbao I, Armadans L, Lazaro JL, et al. Predictive factors for early mortality following liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2003;17(5):401–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvares-da-Silva MR, Reverbel da ST. Comparison between handgrip strength, subjective global assessment, and prognostic nutritional index in assessing malnutrition and predicting clinical outcome in cirrhotic outpatients. Nutrition. 2005;21(2):113–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selberg O, Bottcher J, Tusch G, et al. Identification of high- and low-risk patients before liver transplantation: a prospective cohort study of nutritional and metabolic parameters in 150 patients. Hepatology. 1997;25(3):652–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalaitzakis E, Simren M, Olsson R, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with liver cirrhosis: associations with nutritional status and health-related quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(12):1464–72. doi: 10.1080/00365520600825117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalaitzakis E, Olsson R, Henfridsson P, et al. Malnutrition and diabetes mellitus are related to hepatic encephalopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2007;27(9):1194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huisman EJ, Trip EJ, Siersema PD, et al. Protein energy malnutrition predicts complications in liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(11):982–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834aa4bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merli M, Lucidi C, Giannelli V, et al. Cirrhotic patients are at risk for health care-associated bacterial infections. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):979–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merli M, Giusto M, Gentili F, et al. Nutritional status: its influence on the outcome of patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2010;30(2):208–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien A, Williams R. Nutrition in end-stage liver disease: principles and practice. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(6):1729–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerwin AJ, Nussbaum MS. Adjuvant nutrition management of patients with liver failure, including transplant. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91(3):565–78. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira LG, Anastacio LR, Correia MI. The impact of nutrition on cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(5):554–61. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833b64d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argiles JM, Anker SD, Evans WJ, et al. Consensus on cachexia definitions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(4):229–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argiles J, et al. Cachexia: a new definition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(6):793–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montano-Loza AJ, Meza-Junco J, Prado CM, et al. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.028. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Englesbe MJ, Patel SP, He K, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(2):271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng S, Plank LD, McCall JL, et al. Body composition, muscle function, and energy expenditure in patients with liver cirrhosis: a comprehensive study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(5):1257–66. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberino F, Gatta A, Amodio P, et al. Nutrition and survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrition. 2001;17(6):445–50. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campillo B, Richardet JP, Bories PN. Enteral nutrition in severely malnourished and anorectic cirrhotic patients in clinical practice. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29(6–7):645–51. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)82150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plauth M, Schutz ET. Cachexia in liver cirrhosis. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85(1):83–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]