Abstract

Our laboratory recently reported that a group of novel indole quinuclidine analogues bind with nanomolar affinity to cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptors. This study characterized the intrinsic activity of these compounds by determining whether they exhibit agonist, antagonist, or inverse agonist activity at cannabinoid type-1 and/or type-2 receptors. Cannabinoid receptors activate Gi/Go-proteins that then proceed to inhibit activity of the downstream intracellular effector adenylyl cyclase. Therefore, intrinsic activity was quantified by measuring the ability of compounds to modulate levels of intracellular cAMP in intact cells. Concerning cannabinoid type-1 receptors endogenously expressed in Neuro2A cells, a single analogue exhibited agonist activity, while eight acted as neutral antagonists and two possessed inverse agonist activity. For cannabinoid type-2 receptors stably expressed in CHO cells, all but two analogues acted as agonists; these two exceptions exhibited inverse agonist activity. Confirming specificity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors, modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by all proposed agonists and inverse agonists was blocked by co-incubation with the neutral cannabinoid type-1 antagonist O-2050. All proposed cannabinoid type-1 receptor antagonists attenuated adenylyl cyclase modulation by cannabinoid agonist CP-55,940. Specificity at cannabinoid type-2 receptors was confirmed by failure of all compounds to modulate adenylyl cyclase activity in CHO cells devoid of cannabinoid type-2 receptors. Further characterization of select analogues demonstrated concentration-dependent modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity with potencies similar to their respective affinities for cannabinoid receptors. Therefore, indole quinuclidines are a novel structural class of compounds exhibiting high affinity and a range of intrinsic activity at cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptors.

Keywords: Cannabinoid type-1 receptor, Cannabinoid type-2 receptor, G-protein coupled receptor signaling, cAMP, Drug development, Drug discovery

1. Introduction

Compounds isolated from Cannabis sativa have been utilized historically for a variety of medicinal purposes, including use as analgesics, anti-bacterials, anti-migraines and anti-inflammatory agents (Russo, 2007). Discovery of type-1 (Matsuda et al., 1990) and type-2 (Munro et al., 1993) cannabinoid receptors in the 1990's spurred increased research for additional therapeutic uses of Cannabis products and analogues derived from these natural compounds (Grotenhermen and Muller-Vahl, 2012). Cannabinoid type-1 receptors are present in greatest abundance in the CNS (Herkenham et al., 1990), but also are found in the periphery (Kress and Kuner, 2009; Nogueiras et al., 2008). In contrast, cannabinoid type-2 receptors are most prevalent in immune cells (McCarberg and Barkin, 2007), although also observed in the brain (Van Sickle et al., 2005; Xi et al., 2011). Both receptors are linked to inhibitory G-proteins (Gi/o) that inhibit downstream cAMP production and activate the MAP-kinase cascade (Dalton et al., 2009). Cannabinoid type-1, but not type-2 receptors, also modulate the activity of voltage-gated Ca2+ and inward rectifying K+ ion channels (Mackie et al., 1995).

The major psychoactive cannabinoid isolated from Cannabis sativa, 9Δ-tetrahydrocannabinol (9ΔTHC), acts as a partial agonist at both cannabinoid receptors (Brents et al., 2011; Griffin et al., 1998; Rajasekaran et al., 2013) and is FDA-approved to treat a variety of indications (Grotenhermen and Muller-Vahl, 2012). However, widespread medical use of 9ΔTHC has been limited due to psychoactive effects produced via agonist actions at cannabinoid type-1 receptors (Ameri, 1999). As such, development of cannabinoid agonists with improved therapeutic profiles relative to 9ΔTHC is needed (Grotenhermen and Muller-Vahl, 2012). In addition to promising medical use of cannabinoid type-1 agonists, antagonists for these receptors have been efficaciously employed for weight loss and reduction of obesity-associated cardiometabolic problems (Christopoulou and Kiortsis, 2011). However, adverse psychiatric effects have been attributed to inverse agonist actions at cannabinoid type-1 receptors in the CNS (Taylor, 2009). Therefore, neutral antagonists (Silvestri and Di Marzo, 2012) and cannabinoid ligands restricted to the periphery (Tam et al., 2012) are being developed as anti-obesity agents.

Cannabinoids are currently classified into three structurally distinct groups; endocannabinoids, phytocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids (Pertwee, 1997). Endocannabinoids are endogenous compounds synthesized “on demand” in post-synaptic neurons and communicate in a retrograde fashion (Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). Phytocannabinoids are plant-derived compounds that are often structurally similar to 9ΔTHC (Gertsch et al., 2010). Lastly, synthetic cannabinoids are compounds specifically designed with high affinity for cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptors to alter receptor and/or endocannabinoid function (Pop, 1999).

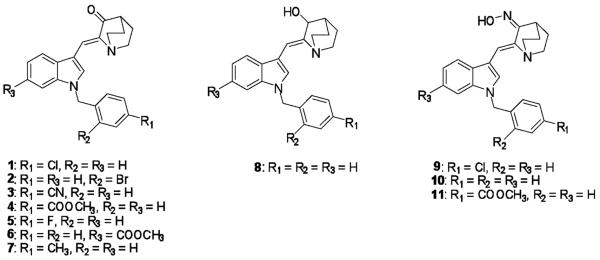

To develop cannabinoids with improved therapeutic properties, we have recently reported the synthesis of a novel class, the indole quinuclidines, that bind with high nanomolar affinity to both types of cannabinoid receptors (Madadi et al., 2013) (Fig. 1). Compounds in this class exhibit varying affinity for both cannabinoid receptors, with most compounds demonstrating slightly higher affinity for cannabinoid type-2 receptors. The aim of the present study was to characterize the intrinsic activity of these novel cannabinoids by determining whether they exhibit agonist, antagonist, or inverse agonist activity at cannabinoid type-1 and/or type-2 receptors.

Fig. 1.

Structures of Indole quinuclidine analogues 1–11 examined in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All indole quinuclidine compounds examined in this study (Fig. 1) were synthesized as described in Methods section 2.3 and dissolved in 100% DMSO to a stock concentration of 10−2 M for in vitro experiments. All other drugs were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). [3H]CP-55,950 (168 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) and [3H]adenine (26 Ci/mmol) was obtained from (Vitrax; Placenia, CA). All other reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA).

2.2. Animals

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences institutional animal care and use committee (e.g., IACUC) approved the animal use protocol employed in this study. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. B6SJL mice were obtained from an in-house breeding colony. All animals were maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Following anesthesia with isoflurane, mice were killed and brains harvested by decapitation and snap frozen using liquid nitrogen for use in membrane preparation (see Methods section 2.5).

2.3. Synthesis of Novel Compounds

The chemical structures of the prepared indole quinuclidines (1–11) are illustrated in Fig. 1. Treating appropriate (Z)-2-(1H-indol-3-yl methylene)quinuclidin-3-ones with a variety of benzyl halides in presence of triethylbenzylammonium chloride in 50% w/v aqueous NaOH solution in DCM afforded (Z)-2-(N-benzylindol-3-ylmethylene)-quinuclidin-3-one derivatives 1–7 (Madadi et al., 2013). Reduction of (Z)-2-(N-benzylindol-3-ylmethylene)-quinuclidin-3-one with sodium borohydride in methanol afforded compound 8, (Z)-2-((1-benzyl-1H-indol-3-yl)methylene)quinuclidin-3-ol. Reaction of analogue 1, (Z)-2-(N-benzylindol-3-ylmethylene)-quinuclidin-3-one and analogue 4, each with hydroxyl amine hydrochloride in the presence of sodium acetate/methanol afforded their respective (2Z,3E)-2-((1-benzyl-1H-indol-3-yl)methylene)-quinuclidin-3-one oximes 9, 10 and 11, respectively. The structures of compounds 1–11 were confirmed by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HRMS (ESI) (Madadi et al., 2013; Sonar et al., 2007).

2.4. Cell Culture

Neuro2A cells, which endogenously express cannabinoid type-1 receptors (Bromberg et al., 2008), Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells stably expressing human cannabinoid type-2 receptors (CHO-hCB2) (Shoemaker et al., 2005) or human mu-opioid receptors (CHO-hMOR) (Seely et al., 2012) were used in this study. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's Modification of Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Cellgro, Manassas, VA) containing 10% FetalPlex™ animal serum complex (Gemini Bio Products, West Sacramento, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (10,000 IU/ml penicillin, 10,000 μg/ml streptomycin; Cellgro, Manassas, VA). Culture media for CHO-hCB2 and CHO-hMOR cells also contained 0.5 mg/ml of the selection antibiotic geniticin (G418; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to maintain stable expression of human cannabinoid type-2 receptors and human mu-opioid receptors. Cells were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator and harvested with PBS (10 mM)/EDTA (1 mM) when culture flasks were approximately 90–100% confluent. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C for future preparation of membrane homogenates, reseeded into flasks for continued cell line culturing or seeded into 24-well plates for adenylyl cyclase experiments (see Methods section 2.7).

2.5. Membrane Preparation

Crude membrane homogenates of mouse brain (for cannabinoid type-1) or CHO-hCB2 cells (for cannabinoid type-2) receptors were prepared with minor modifications as described previously (Madadi et al., 2013). In short, on the day of membrane preparation, frozen whole brains or CHO-hCB2 cell pellets were thawed on ice and homogenized in 20 ml of ice-cold homogenization buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA) by employing a 40 ml Dounce homogenizer. First, ten strokes with a fine grinding pestle “A” were performed on ice, followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 40,000 x g at 4°C. Pellets were then resuspended in 20 ml of homogenization buffer and the homogenization and centrifugation steps were repeated two more times. A final homogenization step using a course grinding pestle “B” was conducted to evenly suspend the homogenates prior to aliquoting and storage at −80°C for future use. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA™ Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

2.6. Competition Receptor Binding

Receptor binding assays were conducted essentially as detailed previously in (Madadi et al., 2013). Each binding sample contained 50 μg (mouse brain) or 25 μg (CHO-hCB2 cells) of membrane homogenates, 0.2 nM of the high affinity non-selective cannabinoid type-1/type-2 agonist [3H]-CP-55,940, 5 mM MgCl2, and increasing concentrations (0.1 nM – 10 μM) of the non-radioactive competitive ligands in an incubation mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) with 0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Assays were performed in triplicate in a final volume of 1ml of incubation mixture. Total binding was defined as the amount of radioactivity observed when 0.2 nM [3H]CP-55,940 was incubated in the absence of any competitor. Non-specific binding was defined as the amount of radioligand binding remaining in the presence of a single 1 μM concentration of non-radioactive WIN-55,212–2, a high affinity non-selective cannabinoid type-1/type-2 agonist. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting non-specific from total binding. Reaction mixtures were mixed and binding allowed to reach equilibrium during an incubation at room temperature for 90 min. Termination of the reactions was achieved by rapid vacuum filtration through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters followed by four 1 ml washes with ice cold filtration buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 7.4 and 0.05% BSA). Filters were then immediately placed into scintillation vials with 4 ml of ScintiverseTM BD cocktail scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). After overnight incubation in scintillation fluid, bound reactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry (Tri Carb 2100 TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer, Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, CT).

2.7. Measurement of Intracellular cAMP Levels in Intact Cells

Adenylyl cyclase assays were conducted similar to experiments reported in (Rajasekaran et al., 2013). Briefly, cells cultured between passages 8 and 18 were seeded into 24-well plates (6.5 × 106 cells per plate) and incubated overnight in a humidified incubator maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. After culturing overnight, growth media in each well was removed and replaced with 0.5 ml of an incubation media containing DMEM with 0.9g/L NaCl, 2.5 μCi/ml [3H]adenine and 0.5 mM isobutyl-methyl-xanthine (IBMX) for 3 hr. The incubation media was then removed and plates were floated briefly on an ice-water bath only long enough to add 0.5ml of test compounds in a Krebs-Ringer-HEPES solution (10 mM HEPES, 110mM NaCl, 25mM Glucose, 55mM Sucrose, 5mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mM IBMX and 10μM forskolin. Plates were immediately transferred to a 37°C water bath for 15 min and all reactions then terminated by addition of 50 μL of 2.2 N HCl to each well. [3H]cAMP was isolated by employing alumina column chromatography. [3H]cAMP present in 4 mls of the final eluate was quantified following addition of 10 ml of scintiverseTM BD cocktail scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry (Tri Carb 2100 TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer, Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, CT).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Curve-fitting and statistical analyses were conducted utilizing GraphPad Prism® v6.0b (GraphPad Software, Inc.; San Diego, CA). Non-linear regression for one-site competition was used to determine the IC50 for competition receptor binding. The Cheng-Prusoff equation (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973) was employed to convert the experimental IC50 values obtained from competition receptor binding experiments to Ki values (a quantitative measure of receptor affinity). Curve fitting of concentration-effect curves via non-linear regression was also employed to determine the ED50 (a measure of potency) and Emax (a measure of efficacy) for the adenylyl cyclase experiments. A one-sample t-test was used to determine whether the modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity produced by a 10 μM concentration of test compounds was significantly different than basal levels in CHO-hMOR cells. Data obtained from three or more experimental groups were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA, followed by either Dunnett's or Tukey's post-hoc comparisons of individual groups. A non-paired Student's t-test was employed to statistically compare data obtained from two experimental groups.

3. Results

3.1. Determination of intrinsic activity of novel indole quinuclidine analogues at cannabinoid type-1 receptors

3.1.1. Screen for cannabinoid type-1 receptor modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by indole quinuclidine analogues

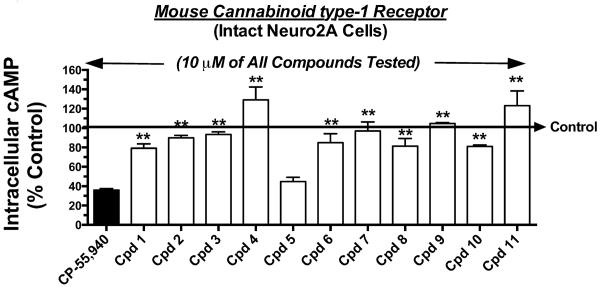

Cannabinoid receptors activate Gi/Go-proteins that then proceed to inhibit activity of the downstream intracellular effector adenylyl cyclase (Dalton et al., 2009). As such, cannabinoid agonists reduce, neutral antagonists have no effect upon, and inverse agonists increase levels of intracellular cAMP (Pertwee, 2005). Therefore, as a measure of intrinsic activity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors, the ability of eleven previously reported indole quinuclidine analogues (Fig. 1, Table 1) (Madadi et al., 2013) to modulate forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity via cannabinoid type-1 receptors endogenously expressed in intact Neuro2A cells (He et al., 2006) was examined (Fig. 2). For these studies, a receptor saturating concentration of each compound (e.g., >10 times Ki value; Table 1) was employed to result in full receptor occupancy, which would be anticipated to produce a maximal level of adenylyl cyclase modulation. As anticipated, the full cannabinoid non-selective agonist CP-55,940 (Xue et al., 1993) CP-55,940 (1 °M) decreased intracellular cAMP levels by 64.1 +/− 1.6% (N=6). When tested at a 10 °M concentration, only one of the eleven analogues examined (5) acted as a full agonist, producing similar levels of adenylyl cyclase inhibition to that of CP-55,940 (55.5 +/− 4.4%, N=3). Indicative of neutral antagonism, eight compounds (1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10) did not significantly alter cAMP concentrations when compared to basal levels. Finally, two compounds (4, 11) produced significant elevations in intracellular cAMP above basal levels, consistent with action as inverse agonists.

Table 1.

Comparison of Cannabinoid type-1 Receptor affinity with potency and efficacy for Adenylyl Cyclase Inhibition produced by Indole Quinuclidine compounds 1–11.

| [3H]CP binding | Adenylyl Cyclase Inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Ki (nM) | IC50 (nM) | Imax (% Inhibition) |

| CP-55,940 | 0.26 ± 0.1†† | 9.8 ± 3.7a | 42.4 ± 3.8a |

| 1 | 31.7 ± 9.25† | NT | NT |

| 2 | 629 ± 201† | NT | NT |

| 3 | 55.3 ± 8.89† | NT | NT |

| 4 | 953 ±162† | NT | NT |

| 5 | 9.23 ± 0.64† | 243 ± 57.5b | 49.0 ± 2.0a |

| 6 | 85.7 ± 15.9† | NT | NT |

| 7 | 113 ± 21.0 | NT | NT |

| 8 | 540 ± 64.2† | NT | NT |

| 9 | 95.7 ± 2.03† | NT | NT |

| 10 | 357 ± 52.2† | NT | NT |

| 11 | 336 ± 29.0 | NT | NT |

| WIN-55,212-2 | NT | 3.4 ± 2.1a | 40.3 ± 1.2a |

| WIN-55,212-2 + Compound 3 | NT | 55.0 ± 17.7c | 38.0 ± 3.6a |

Values previously reported (Madadi et al., 2013)

Values previously reported (Brents et al., 2011)

Values designated by different letters are significantly different. P<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey Post-hoc test; Reported as mean ± S.E.M., n=3–4

NT = Not Tested

Fig. 2. Screen for intrinsic activity of indole quinuclidine analogues acting at cannabinoid type-1 receptors via modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity.

A receptor-saturating concentration (10μM) of each indole quinuclidine test compound was examined for cannabinoid type-1 modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in intact Neuro2A cells. The full cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist CP-55,940 (1 μM) produced maximal inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. Test compounds produced a range of potential intrinsic activity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors when compared to CP-55,940. The “Control” arrow represents the levels of intracellular [3H]cAMP occurring in the presence of 10 μM forskolin in the absence of any cannabinoid ligand. Values designated by asterisks are significantly different than activity produced by CP-55,940 (*P<0.05, **P<0.01; One Way ANOVA with Dunnett's Multiple Comparison post-hoc test).

3.1.2. Confirmation that novel indole quinuclidine agonists, antagonists and inverse agonists produce observed effects In Neuro2A cells via action at cannabinoid type-1 receptors

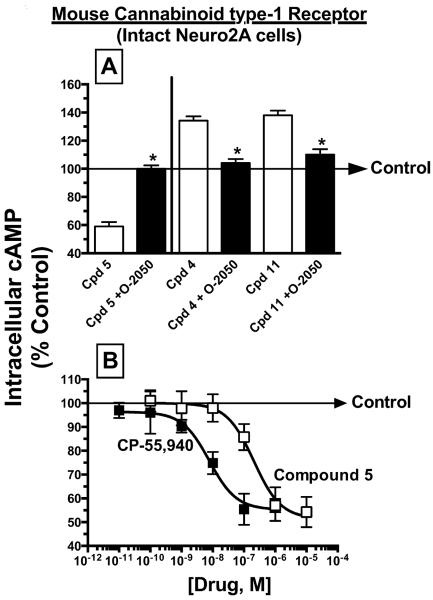

Experiments were next conducted to validate that the observed modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity produced by indole quinuclidine compounds was due to specific interaction with endogenous cannabinoid type-1 receptors expressed in Neuro2A cells. Data presented in Fig. 3A demonstrate that inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity produced by the apparent cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonist, compound 5 (1 °M), was completely blocked by 5 min pre-incubation with 1 °M of the cannabinoid type-1 receptor neutral antagonist, O-2050 (Gardner and Mallet, 2006). Similarly, O-2050 pre-incubation eliminated the increase in adenylyl cyclase activity produced by 10 °M of the apparent cannabinoid type-1 receptor inverse agonists, analogues 4 and 11. These data confirm that compound 5 does indeed act as agonist, and analogues 4 and 11 act as inverse agonists, at cannabinoid type-1 receptors expressed in Neuro2A cells.

Fig. 3. Confirmation that compound 5 acts as an agonist, while analogues 4 and 11 act as inverse agonists at cannabinoid type-1 receptors expressed in intact Neuro2A cells.

Panel A; Modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by the apparent cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonist 5 (1 μM) or cannabinoid type-1 receptor inverse agonists 4 (10 μM) and 11 (10 μM) in Neuro2A cells endogenously expressing cannabinoid type-1 receptors was completely blocked by 5 min pre-incubation with 1 μM of the cannabinoid type-1 receptor neutral antagonist O-2050. Panel B; The cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist CP-55,940 and the novel indole quinuclidine cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonist 5 produced a concentration-dependent reduction in intracellular cAMP levels in Neuro2A cells with high potency and efficacy (see Table 1 for specific IC50 and Imax values). The “Control” arrow represents the levels of intracellular [3H]cAMP occurring in the presence of 10 μM forskolin in the absence of any cannabinoid ligand. Values designated by asterisks are significantly different than activity produced by IQD compound alone (*P<0.05, Students t-test).

To further characterize the agonist actions of compound 5 (the only cannabinoid type-1 agonist identified by the initial adenylyl cyclase screen), full concentration-effect curves for modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by this compound were conducted (Fig. 3B). Serving as a positive control, the full cannabinoid receptor agonist CP-55,940 produced inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity in intact Neuro2A cells (N=4) with high potency (e.g., IC50 of 9.8±3.7 nM) and efficacy (e.g., Imax of 42.4±3.8 % inhibition) (Table 1). The novel indole quinuclidine agonist, compound 5, also produced a concentration-dependent reduction in intracellular cAMP levels (N=6) with an IC50 of 243±57.5 nM and Imax of 49.0±2.0 % inhibition (Table 1). As expected, compound 5 and CP-55,940 demonstrated similar rank orders of potency for adenylyl cyclase inhibition and affinity for cannabinoid type-1 receptors (e.g., compound 5 exhibited both lower adenylyl cyclase potency and cannabinoid type-1 receptor affinity than CP-55,940; Table 1). Consistent with results presented for the initial screen for adenylyl cyclase inhibition employing a single receptor saturating concentration (Fig. 2), the concentration-effect data presented here similarly confirm that compound 5 and CP-55,940 both act as full agonists at cannabinoid type-1 receptors expressed in Neuro2A cells with similar efficacy.

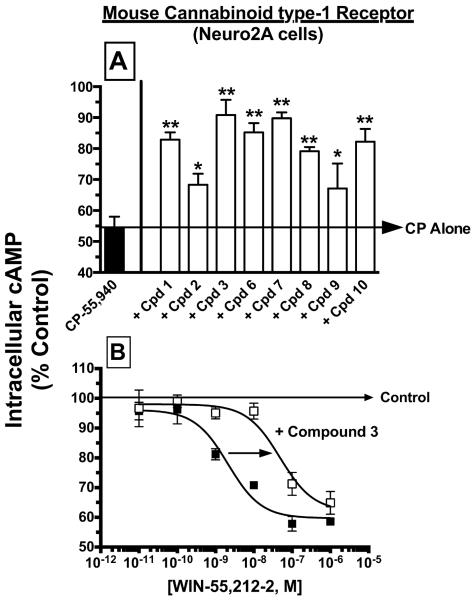

To verify that the remaining eight indole quinuclidine compounds that produced no effect on adenylyl cyclase activity in the initial intrinsic activity screen were indeed neutral antagonists at cannabinoid type-1 receptors, Neuro2A cells were pre-incubated with a 10 °M concentration of each analogue for five min followed by co-incubation with an EC90 concentration (10 nM) of the full cannabinoid agonist CP-55,950 (Fig. 4A). CP-55,950 reduced intracellular cAMP levels by 45.7 +/− 3.7% when administered alone (N=6). As expected for drugs acting as neutral antagonists, pre-incubation with all compounds (N=3) significantly attenuated cannabinoid type-1 receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity produced by CP-55,940.

Fig. 4. Confirmation that eight Indole quinuclidine analogues act as antagonists at cannabinoid type-1 receptors expressed in intact Neuro2A cells.

Panel A; Modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by the full cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist CP-55,940 (10 nM) in Neuro2A cells endogenously expressing cannabinoid type-1 receptors was significantly attenuated by 5 min pre-incubation with 10 μM of all eight indole quinuclidine analogues. Panel B; Co-incubation with the indole quinuclidine cannabinoid type-1 receptor antagonist 3 (1 μM) produced a 16-fold parallel shift-to-the-right in the concentration-effect curve for reduction in intracellular cAMP levels in Neuro2A cells produced by the full cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist WIN-55,212-2 (Kb = 55.5 nM). The “Control” arrow represents the levels of intracellular [3H]cAMP occurring in the presence of 10 μM forskolin in the absence of any cannabinoid ligand. Values designated by asterisks are significantly different than activity produced by CP-55,940 alone (*P<0.05, **P<0.01; One Way ANOVA with Dunnett's Multiple Comparison post-hoc test).

To further characterize the antagonist actions of indole quinuclidine compounds at cannabinoid type-1 receptors, the antagonist dissociation constant (e.g., Kb value) was determined for one of the two analogues exhibiting the highest affinity for cannabinoid type-1 receptors (e.g., compound 3, Ki = 55.3 nM; Table 1). When examined alone, the well characterized full cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist WIN-55,212-2 (Pop, 1999) inhibited adenylyl cyclase activity in Neuro2A cells (N=3) with high potency (e.g., IC50 of 3.4 ± 2.1 nM) and efficacy (e.g., Imax of 40.3 ± 1.2 % inhibition) (Fig. 4B; Table 1). Co-incubation with compound 3 (1 μM) produced a parallel, rightward shift in the concentration-effect curve of WIN-55,212-2, decreasing potency to 55.0 +/− 17.7 nM (N=3), while having no effect on efficacy (e.g., Imax of 38.0 ± 3.6 % inhibition). The Kb value for compound 3 derived from these experimental data was 55.5 +/− 19.9 nM, which is remarkably consistent with the previously determined affinity of this indole quinuclidine analogue for cannabinoid type-1 receptors (e.g., Ki of 55.3 ± 8.89, Table 1). Collectively, these results suggest that compound 3, and likely the other seven indole quinuclidine analogues examined, act as competitive neutral antagonists at cannabinoid type-1 receptors expressed in Neuro2A cells for regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity.

3.2. Determination of intrinsic activity of novel indole quinuclidines at cannabinoid type-2 receptors

3.2.1. Screen for cannabinoid type-2 receptor modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by indole quinuclidine analogues

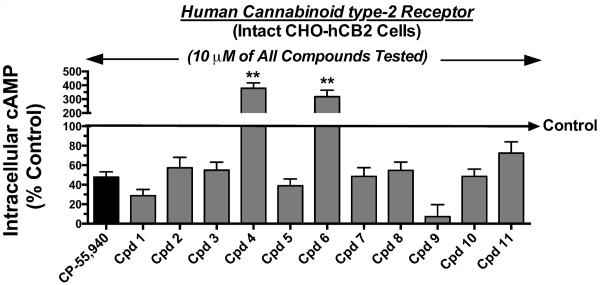

Similar experiments as those conducted for cannabinoid type-1 receptors, were performed to characterize the intrinsic activity of all indole quinuclidine compounds at human cannabinoid type-2 receptors stably expressed in CHO-hCB2 cells. As a measure of intrinsic activity, the ability of all indole quinuclidine compounds to modulate forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity via cannabinoid type-2 receptors stably expressed in intact CHO-hCB2 cells was examined (Fig. 5). A 10 μM concentration of all indole quinuclidine compounds was tested to produce full receptor occupancy (e.g., >10 x Ki value; Table 2). The full agonist CP-55,940 reduced intracellular cAMP levels by 52.2 +/− 5.5% (N=6) in CHO-hCB2 cells. Consistent with actions of a full agonist, nine of the eleven indole quinuclidine compounds examined (1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11) produced levels of adenylyl cyclase inhibition that were not significantly different from that induced by CP-55,940. The two remaining compounds (4 and 6) exhibited obvious inverse agonist activity in CHO-hCB2 cells, increasing cAMP concentrations by 278 +/− 38.6% (N=4) and 218 +/− 46.3% (N=4) above basal levels, respectively.

Fig. 5. Screen for intrinsic activity of indole quinuclidine analogues acting at cannabinoid type-2 receptors via modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity.

A receptor-saturating concentration (10μM) of each indole quinuclidine test compound was examined for cannabinoid type-2 modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in intact CHO-hCB2 cells, respectively. The full cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist CP-55,940 (1 μM) produced maximal inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. Test compounds produced a range of potential intrinsic activity at cannabinoid type-2 receptors when compared to CP-55,940. The “Control” arrow represents the levels of intracellular [3H]cAMP occurring in the presence of 10 μM forskolin in the absence of any cannabinoid ligand. Values designated by asterisks are significantly different than activity produced by CP-55,940 (*P<0.05, **P<0.01; One Way ANOVA with Dunnett's Multiple Comparison post-hoc test).

Table 2.

Comparison of Cannabinoid type-2 Receptor affinity with potency and efficacy fo Adenylyl Cyclase Inhibition produced by Indole Quinuclidine compounds 1–11.

| [3H]CP binding | Adenylyl Cyclase Inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Ki (nM) | IC50 (nM) | Imax (% Inhibition) |

| CP-55,940 | 0.4 ± 0.2†† | 3.3 ± 1.4††,a | 67.3 ± 3.5††,a |

| 1 | 20.3 ± 7.43† | 7.5 ± 1.8b | 63.0 ± 5.2a,b |

| 2 | 333 ±157† | NT | NT |

| 3 | 114 ± 36.2† | 59.8 ± 39.9c | 37.7 ± 2.0b |

| 4 | 588 ± 237† | NT | NT |

| 5 | 1.33 ± 0.45† | 3.6 ± 2.5a | 52.0 ± 4.5c |

| 6 | 2.50 ± 0.49† | 48.0 ± 3.9c | −200.3 ± 8.6d |

| 7 | 71.0 ± 12.0 | NT | NT |

| 8 | 55.3 ± 3.1† | NT | NT |

| 9 | 107 ± 8.75† | NT | NT |

| 10 | 68.6 ± 7.27† | NT | NT |

| 11 | 271 ± 4.0 | NT | NT |

Values previously reported (Madadi et al., 2013)

Values previously reported (Rajasekaran et al., 2013)

Values designated by different letters are significantly different. P<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey Post-hoc test; Reported as mean ± S.E.M., n=3–4

NT = Not Tested

3.2.2. Confirmation that novel indole quinuclidine agonists and inverse agonists produce observed effects in CHO-hCB2 cells via action at cannabinoid type-2 receptors

Demonstration that indole quinuclidines regulate adenylyl cyclase activity in intact CHO-hCB2 cells via cannabinoid type-2 receptors was not confirmed by co-incubation of analogues with selective neutral antagonists because three different cannabinoid type-2 receptor antagonist/inverse agonists (e.g., AM-630, JTE-907 and SR-144528) act as inverse agonists in this cell line, producing concentration-dependent increases in intracellular cAMP when administered alone (Rajasekaran et al., 2013).

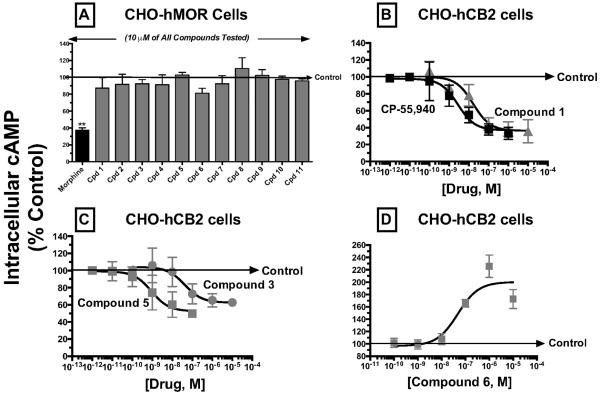

Therefore, to confirm that the intrinsic activity observed for modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity produced by indole quinuclidine compounds was due to specific interaction with cannabinoid type-2 receptors stably expressed in CHO-hCB2 cells, the ability of the test compounds to alter intracellular cAMP levels was examined in CHO cells devoid of human cannabinoid type-2 receptors, but stably expressing mu-opioid receptors (e.g., CHO-hMOR cells; Fig. 6A). A receptor saturating concentration (1 μM for morphine and 10 μM for IQDs; Table 2) was employed for all assays. Confirming use as a positive control, the mu-opioid receptor agonist morphine (Williams et al., 2013) inhibited adenylyl cyclase activity by 62.6 +/− 2.8% (N=6) in CHO-hMOR cells. In contrast, none of the indole quinuclidine compounds tested significantly altered basal cAMP levels in CHO-hMOR cells (N=3). These results confirm that human cannabinoid type-2 receptors in transfected CHO-hCB2 cells are required to observe regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity by the indole quinuclidine compounds examined.

Fig. 6. Confirmation that indole quinuclidine analogues act as agonists and inverse agonists at cannabinoid type-2 receptors expressed in intact CHO-hCB2 cells.

Panel A; A receptor-saturating concentration (10μM) of each indole quinuclidine test compound or the mu-opioid receptor agonist morphine (1μM) was examined for modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in intact CHO-hMOR cells. Although morphine (black bar) produced significant inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity, all test compounds examined (green bars) failed to significantly alter basal cAMP levels. Panels B–D; The cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptor agonist CP-55,940, novel indole quinuclidine cannabinoid type-2 receptor agonists (compounds 1, 3 and 5) and inverse agonist (compound 6) produced concentration-dependent modulation of intracellular cAMP levels in CHO-hCB2 cells with high potency and efficacy (see Table 2 for specific IC50/ED50 and Imax/Emax values). The “Control” arrow represents the levels of intracellular [3H]cAMP occurring in the presence of 10 μM forskolin in the absence of any cannabinoid ligand. Values designated by asterisks are significantly different than basal AC-activity (**P<0.01; One Sample t-test).

To further characterize the agonist actions of indole quinuclidine compounds at cannabinoid type-2 receptors, three analogues exhibiting the highest affinity for cannabinoid type-2 receptors (e.g., compound 5, Ki = 1.3 nM; compound 1, Ki = 20.3 nM; compound 3, Ki = 114 nM) were selected to conduct full concentration-effect curves for modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity (Fig. 6B and 6C). The full agonist CP-55,940 (1 μM) produced a concentration-dependent reduction in intracellular cAMP levels (N=6) in intact CHO-hCB2 cells with an IC50 of 3.3 ± 1.4 nM and Imax of 67.3 ± 3.5 % inhibition (Fig. 6B; Table 2). Similarly, compound 1 (Fig. 6B; N=3), compound 3 (Fig. 6C; N=3) and compound 5 (Fig. 6C; N=3) inhibited adenylyl cyclase activity with high potency (3.3 – 59.8 nM) and efficacy (37.7 – 67.3% inhibition) (Table 2). As anticipated, CP-55,940 and all three indole quinuclidine compounds demonstrated similar rank orders of potency for adenylyl cyclase inhibition when compared with affinity for cannabinoid type-2 receptors (e.g., CP-55,940 > 5 > 1 > 3; Table 2). Data obtained from full concentration-effect curves suggest that CP-55,940 and compound 1 act as full agonists (Fig. 6B), while analogues 3 and 5 are significantly less efficacious and act as partial agonists (Fig. 6C; Table 2). These data are slightly different from the prediction by the initial screen for modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity (which indicated that all three of these indole quinuclidine compounds produce similar levels of adenylyl cyclase inhibition; Fig. 5),

Lastly, to more fully examine the inverse agonist properties of indole quinuclidine compounds at cannabinoid type-2 receptors, full concentration-effect curves were performed on compound 6, the inverse agonist exhibiting the highest affinity for cannabinoid type-2 receptors (e.g., 2.50 ± 0.49 nM; Table 2). Compound 6 produced a concentration-dependent increase in cAMP levels in intact CHO-hCB2 cells with high potency (ED50) of 48.0 ± 3.9 nM and efficacy (Emax) of 200 ± 8.6% (Fig. 6D; Table 2).

3.3 Physicochemical Properties of Indole Quinuclidine Analogues

The physicochemical properties of the indole quinuclidine analogues examined in this study were assessed to determine the potential for this novel class to serve as a scaffold for future therapeutic drug development. All eleven analogues comply with Pardridge's rules (Pardridge, 2005) for CNS penetration. Specifically, the number of hydrogen bonds is less than 8–10, the molecular weight is less than 400–500 and no analogues are acids. The physicochemical properties of all compounds also generally satisfy the CNS permeability rules set by Clark and Lobell et al (Di et al., 2009) for small molecule penetrance of the blood brain barrier; (1) the number of N + O is less than 6 and the range is 2–5, (2) the polar surface area is less than 60–70 with a range of 23–65, (3) the molecular weight is less than 450, (4) the ClogP – (N+O) is greater than zero with a range from 4.15 to 5.77, and finally (5) the Log D of most compounds is between 1 and 3 with a range of 2.06 to 3.88.

In a previous pharmacokinetic study on a representative indole quinuclidine analog, Z-(±)-2-(1-benzylindole-3-ylmethylene) azabicyclo[2.2.2]- octane-3-ol, (analogue 8), the bioavailability after oral administration was determined by comparing plasma concentrations after oral delivery with those after intravenous administration (Al-Ghananeem et al., 2007). After oral delivery, the average Cmax was 1,710 ± 503 ng/ml and the AUC was found to be 3561 ± 670 ng min kg/ml mg. The oral bioavailability was found to be 6.2%. Furthermore, the compound did not produce any acute toxicity up to a dose of 120 mg/kg (Geng et al., 2009).

4. Discussion

The intrinsic activity for a novel class of indole quinuclidine ligands was characterized by determining whether individual compounds exhibited agonist, antagonist, or inverse agonist activity at cannabinoid type-1 and/or cannabinoid type-2 receptors. Intrinsic activity was assessed by the ability of test compounds to alter production of cAMP by the downstream intracellular effector adenylyl cyclase in intact cells. For cannabinoid type-1 receptors endogenously expressed in Neuro2A cells, studies identified one agonist, eight neutral antagonists and two inverse agonists (Table 3). Concerning cannabinoid type-2 receptors stably expressed in CHO-hCB2 cells, of the eleven compounds examined, nine acted as agonists and two exhibited inverse agonist activity (Table 3). Further characterization of select compounds with highest affinity for cannabinoid receptors demonstrated concentration-dependent modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity with a rank order of potency similar to their respective affinities for cannabinoid receptors (Tables 1 & 2). Collectively, we propose that the indole quinuclidine structural scaffold can be employed to develop novel therapeutic compounds acting at cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptors, which exhibit high affinity and a range of intrinsic activity for use in treatment of a wide variety of diseases.

Table 3.

Summary of Intrinsic Activity† and Selectivity†† for Indole Quinuclidine compounds 1–11 at Human Cannabinoid type-1 Receptors and Cannabinoid type-2 Receptors.

| Compound | CB1R | CB2R | CB1/CB2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP-55,940 | Agonist | Agonist | 0.65 |

| 1 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 1.56 |

| 2 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 1.89 |

| 3 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 0.49 |

| 4 | Inverse Agonist | Inverse Agonist | 1.62 |

| 5 | Agonist | Agonist | 6.94 |

| 6 | Neutral Antagonist | Inverse Agonist | 34.3 |

| 7 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 1.59 |

| 8 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 9.56 |

| 9 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 0.89 |

| 10 | Neutral Antagonist | Agonist | 5.20 |

| 11 | Inverse Agonist | Agonist | 1.24 |

Intrinsic Activity – Modulation of AC-activity compared to full agonist CP-55,940

Selectivity – Calculated by CBl-Ki value divided CB2-Ki value

Results presented here indicate that the indole quinuclidine scaffold might be useful to design cannabinoid drugs exhibiting distinct pharmacological properties that can be grouped into five general categories; (1) cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonists, (2) cannabinoid type-1 receptor neutral antagonist/inverse agonists, (3) cannabinoid type-2 receptor agonists, (4) cannabinoid type-2 receptor inverse agonists and (5) compounds with dual action at both cannabinoid type-1 and type-2 receptors. The only drugs acting via cannabinoid receptors currently approved by the FDA are preparations that include the cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonist Δ9-THC, or an analogue, as a primary constituent (e.g., Cesamet, Marinol, and Sativex) (Davis et al., 2007). These drugs have been approved for alleviating neuropathic and cancer pain, management of spasticity in multiple sclerosis and relief of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (Turcotte et al., 2010). However, pre-clinical research of cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonists has demonstrated that this class of ligands may additionally have therapeutic promise for a variety of other disease states including anxiety, depression, epilepsy, glaucoma, drug-dependence, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease (Pertwee, 2012). Despite such potential benefit, widespread use of cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonists is significantly limited due to psychotropic actions resulting from activation of cannabinoid type-1 receptors in the CNS (Ameri, 1999). To avoid these adverse effects, “peripherally restricted” cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonists are being developed to limit drug entry into the CNS to treat diseases in which activation of cannabinoid type-1 receptors outside of the nervous system would be beneficial (Pertwee, 2012). Compound 5 was the only analogue examined in this study that exhibited agonist activity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors. Therefore, carefully designed analogues of compound 5 with incorporation of hydrophilic moieties might yield novel full agonists with poor CNS penetration, with the ability to efficaciously activate peripherally located cannabinoid type-1 receptors.

In addition to development of cannabinoid type-1 receptor agonists, compounds acting as antagonists and/or inverse agonists at this receptor are also being examined for therapeutic use. For example, the cannabinoid type-1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, rimonabant, was briefly marketed as an anti-obesity medication, but was quickly withdrawn due to severe psychiatric effects thought to be due to inverse agonist activity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors in the CNS (Taylor, 2009). In addition to obesity, inverse agonists and neutral antagonists of cannabinoid type-1 receptors show promise for treatment of cardio-metabolic disorders (Van Gaal et al., 2008) and to reduce drug addiction and craving (Janero, 2012). Therefore, use of peripherally restricted inverse agonists (Tam et al., 2012) or neutral cannabinoid type-1 receptor antagonists (Silvestri and Di Marzo, 2012) could potentially overcome many adverse effects associated with activation or inhibition of centrally located cannabinoid receptors. Interestingly, eight of the eleven indole quinuclidine compounds evaluated here acted as neutral antagonists and two exhibited inverse activity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors. Analysis of structure-activity relationships for these compounds in relation to neutral antagonist or inverse activity at cannabinoid type-1 receptors may therefore prove very beneficial for development of anti-obesity and anti-addiction drugs. Furthermore, development of peripherally restricted indole quinuclidine analogues may also yield clinically useful cannabinoid type-1 receptor neutral antagonists and/or inverse agonists.

Although most research to date has focused on cannabinoids acting at cannabinoid type-1 receptors, there are significant advantages to developing drugs that act selectively at cannabinoid type-2 receptors. For example, cannabinoid type-2 receptor agonists have been shown to produce anti-angiogenic and anti-proliferative effects in the treatment of various forms of cancers (Vidinsky et al., 2012), to reduce chronic neuropathic pain (Wilkerson et al., 2012), and to beneficially modulate cytokine levels in immunologically-based disease states (Cabral and Griffin-Thomas, 2009). Since cannabinoid type-2 receptors participate in inflammatory processes via modulation of cytokine release, both agonists (Ehrhart et al., 2005) and newly developed classes of antagonists/inverse agonists (Lunn et al., 2008; Pasquini et al., 2011; Pasquini et al., 2010; Pasquini et al., 2012) have been shown to reduce inflammation and hyperalgesia associated with several disease states. Importantly, four indole quinuclidine compounds examined in this study demonstrate from 5-, to over 30-, fold selectivity for binding to cannabinoid type-2 relative to type-1 receptors (Table 3) (Madadi et al., 2013). In addition, the indole quinuclidine analogues identified here exhibit either agonist (e.g., compound 8, 10-fold type-2 selective) or inverse agonist (e.g., compound 6, 34-fold type-2 selective) activity at cannabinoid type-2 receptors. These observations indicate that the indole quinuclidine structural scaffold will prove very useful for development of either novel selective cannabinoid type-2 receptor agonists or inverse agonists.

A major aim of current drug development of cannabinoid ligands is to identify compounds exhibiting high selectively for either cannabinoid type-1 or type-2 receptors (Bosier et al., 2010). While this approach may be appropriate in many instances, distinct advantages may also exist for development of a single drug that exhibits desirable intrinsic activity at both receptors simultaneously. Such “dual-action” cannabinoid ligands would likely be useful to treat obesity, in which administration of cannabinoid type-1 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists (Janero, 2012) or cannabinoid type-2 agonists (Yang et al., 2012) independently has already demonstrated clear therapeutic benefits. Furthermore, a phytocannabinoid derived from Cannabis sativa, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin, exhibits both cannabinoid type-1 receptor inverse agonist and cannabinoid type-2 receptor agonist activity (Pertwee, 2008), while also appearing to reverse insulin sensitivity in two mouse models of obesity (Wargent et al., 2013). In the present study, five indole quinuclidine compounds examined acted as dual cannabinoid type-1 receptor neutral antagonists / cannabinoid type-2 receptor agonists with similar relatively high affinity for both receptors (e.g., compounds 1, 2, 3, 7 and 9). Therefore, the indole quinuclidine scaffold clearly offers an excellent basis for development of dual action cannabinoid drugs.

Comparison of the overall affinities of the eleven indole quinuclidine for cannabinoid type-1 receptors (Table 1) and cannabinoid type-2 receptors (Table 2) indicates that quinuclidin-3-ols and quinuclidin-3-one oximes generally have less affinity than quinuclidin-3-ones. Furthermore, replacing the benzylic 4-chloro group in compound 1 with a 4-fluoro group (compound 5) improves affinity for cannabinoid type-2 receptor by 20-fold (Table 2), and significantly increases intrinsic activity, resulting in full agonist activity at both cannabinoid receptors (Tables 1 and 2). Indole quinuclidine analogues 6, 8 and 10 were found to exhibit good cannabinoid type-2 selectivity over type-1 receptors (e.g., analogue 6 was 34-fold more selective for cannabinoid type-2 receptors), suggesting that the presence of an unsubstituted N-benzyl moiety may improve selectivity for cannabinoid type-2 receptors. Incorporating a COOCH3 group at the indolic 6-position (compound 6) also resulted in high selectivity for cannabinoid type-2 receptors. Importantly, addition of the COOCH3 group at either the 4-benzyl position (e.g., compounds 4 and 11) or the indolic 6-position (e.g., compound 6) appears to impart negative intrinsic activity, affording compounds that act as inverse agonists. Combined with relatively favorable physicochemical properties, these structure-activity relationships will significantly aid future design and development of novel cannabinoid receptor indole quinuclidine ligands with desired selectivity and intrinsic activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was support in part by NCI/NIH Grant number CA 140409 and an Arkansas Research Alliance grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Chemical Compounds: [3H]CP-55940 (PubChem CID: 5311056); CP-55,940 (PubChem CID: 104895); WIN-55,212-2 (PubChem CID: 5311501); O-2050 (PubChem CID: 16102146); Morphine (PubChem CID: 5288826)

References

- Al-Ghananeem AM, Albayati ZF, Malkawi A, Sonar VN, Freeman ML, Crooks PA. A pharmacokinetic study on Z-(+/−)-2-(1-benzylindole-3-ylmethylene)azabicyclo[2.2.2]octane-3-ol; a novel radio-sensitization agent. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2007;60:915–919. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameri A. The effects of cannabinoids on the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999;58:315–348. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosier B, Muccioli GG, Hermans E, Lambert DM. Functionally selective cannabinoid receptor signalling: therapeutic implications and opportunities. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Reichard EE, Zimmerman SM, Moran JH, Fantegrossi WE, Prather PL. Phase I hydroxylated metabolites of the K2 synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 retain in vitro and in vivo cannabinoid 1 receptor affinity and activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:c21917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg KD, Ma'ayan A, Neves SR, Iyengar R. Design logic of a cannabinoid receptor signaling network that triggers neurite outgrowth. Science. 2008;320:903–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1152662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral GA, Griffin-Thomas L. Emerging role of the cannabinoid receptor CB2 in immune regulation: therapeutic prospects for neuroinflammation. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009;11:e3. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff W. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (i50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulou FD, Kiortsis DN. An overview of the metabolic effects of rimonabant in randomized controlled trials: potential for other cannabinoid 1 receptor blockers in obesity. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2011;36:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton GD, Bass CE, Van Horn CG, Howlett AC. Signal transduction via cannabinoid receptors. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 2009;8:422–431. doi: 10.2174/187152709789824615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Maida V, Daeninck P, Pergolizzi J. The emerging role of cannabinoid neuromodulators in symptom management. Support. Care Cancer. 2007;15:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di L, Kerns EH, Carter GT. Drug-like property concepts in pharmaceutical design. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009;15:2184–2194. doi: 10.2174/138161209788682479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart J, Obregon D, Mori T, Hou H, Sun N, Bai Y, Klein T, Fernandez F, Tan J, Shytle D. Stimulation of cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) suppresses microglial activation. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner A, Mallet PE. Suppression of feeding, drinking, and locomotion by a putative cannabinoid receptor `silent antagonist'. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;530:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng L, Rachakonda G, Morre DJ, Morre DM, Crooks PA, Sonar VN, Roti JL, Rogers BE, Greco S, Ye F, Salleng KJ, Sasi S, Freeman ML, Sekhar KR. Indolyl-quinuclidinols inhibit ENOX activity and endothelial cell morphogenesis while enhancing radiation-mediated control of tumor vasculature. FASEB J. 2009;23:2986–2995. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-130005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertsch J, Pertwee RG, Di Marzo V. Phytocannabinoids beyond the Cannabis plant -do they exist? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:523–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin G, Atkinson PJ, Showalter VM, Martin BR, Abood ME. Evaluation of cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists using the guanosine-5'-O-(3-[35S]thio)-triphosphate binding assay in rat cerebellar membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;285:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhermen F, Muller-Vahl K. The therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2012;109:495–501. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JC, Neves SR, Jordan JD, Iyengar R. Role of the Go/i signaling network in the regulation of neurite outgrowth. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2006;84:687–694. doi: 10.1139/y06-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 1990;87:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janero DR. Cannabinoid-1 receptor (CB1R) blockers as medicines: beyond obesity and cardiometabolic disorders to substance abuse/drug addiction with CB1R neutral antagonists. Expert opinion on emerging drugs. 2012;17:17–29. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2012.660916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Kuner R. Mode of action of cannabinoids on nociceptive nerve endings. Exp. Brain Res. 2009;196:79–88. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1762-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn CA, Reich EP, Fine JS, Lavey B, Kozlowski JA, Hipkin RW, Lundell DJ, Bober L. Biology and therapeutic potential of cannabinoid CB2 receptor inverse agonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153:226–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K, Lai Y, Westenbroek R, Mitchell R. Cannabinoids activate an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance and inhibit Q-type calcium currents in AtT20 cells transfected with rat brain cannabinoid receptor. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6552–6561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06552.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madadi NR, Penthala NR, Brents LK, Ford BM, Prather PL, Crooks PA. Evaluation of (Z)-2-((1-benzyl-1H-indol-3-yl)methylene)-quinuclidin-3-one analogues as novel, high affinity ligands for CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:2019–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarberg BH, Barkin RL. The future of cannabinoids as analgesic agents: a pharmacologic, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic overview. Am. J. Ther. 2007;14:475–483. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3180a5e581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas K, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueiras R, Veyrat-Durebex C, Suchanek PM, Klein M, Tschop J, Caldwell C, Woods SC, Wittmann G, Watanabe M, Liposits Z, Fekete C, Reizes O, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Tschop MH. Peripheral, but not central, CB1 antagonism provides food intake-independent metabolic benefits in diet-induced obese rats. Diabetes. 2008;57:2977–2991. doi: 10.2337/db08-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini S, De Rosa M, Pedani V, Mugnaini C, Guida F, Luongo L, De Chiaro M, Maione S, Dragoni S, Frosini M, Ligresti A, Di Marzo V, Corelli F. Investigations on the 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid motif. 4. Identification of new potent and selective ligands for the cannabinoid type 2 receptor with diverse substitution patterns and antihyperalgesic effects in mice. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:5444–5453. doi: 10.1021/jm200476p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini S, Ligresti A, Mugnaini C, Semeraro T, Cicione L, De Rosa M, Guida F, Luongo L, De Chiaro M, Cascio MG, Bolognini D, Marini P, Pertwee R, Maione S, Di Marzo V, Corelli F. Investigations on the 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid motif. 3. Synthesis, structure-affinity relationships, and pharmacological characterization of 6-substituted 4-quinolone-3-carboxamides as highly selective cannabinoid-2 receptor ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5915–5928. doi: 10.1021/jm100123x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini S, Mugnaini C, Ligresti A, Tafi A, Brogi S, Falciani C, Pedani V, Pesco N, Guida F, Luongo L, Varani K, Borea PA, Maione S, Di Marzo V, Corelli F. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological characterization of indol-3-ylacetamides, indol-3-yloxoacetamides, and indol-3-ylcarboxamides: potent and selective CB2 cannabinoid receptor inverse agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:5391–5402. doi: 10.1021/jm3003334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997;74:129–180. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)82001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Pharmacological actions of cannabinoids. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2005:1–51. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153:199–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Targeting the endocannabinoid system with cannabinoid receptor agonists: pharmacological strategies and therapeutic possibilities. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological sciences. 2012;367:3353–3363. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop E. Cannabinoids, endogenous ligands and synthetic analogs. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1999;3:418–425. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)80062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran M, Brents LK, Franks LN, Moran JH, Prather PL. Human metabolites of synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073 bind with high affinity and act as potent agonists at cannabinoid type-2 receptors. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013;269:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB. History of cannabis and its preparations in saga, science, and sobriquet. Chemistry & biodiversity. 2007;4:1614–1648. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seely KA, Brents LK, Franks LN, Rajasekaran M, Zimmerman SM, Fantegrossi WE, Prather PL. AM-251 and rimonabant act as direct antagonists at mu-opioid receptors: Implications for opioid/cannabinoid interaction studies. Neuropharmacol. 2012;63:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JL, Joseph BK, Ruckle MB, Mayeux PR, Prather PL. The endocannabinoid noladin ether acts as a full agonist at human CB2 cannabinoid receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;314:868–875. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri C, Di Marzo V. Second generation CB1 receptor blockers and other inhibitors of peripheral endocannabinoid overactivity and the rationale of their use against metabolic disorders. Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2012;21:1309–1322. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.704019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonar VN, Thirupathi Reddy Y, Sekhar KR, Sasi S, Freeman ML, Crooks PA. Novel substituted (Z)-2-(N-benzylindol-3-ylmethylene)quinuclidin-3-one and (Z)-(+/−)-2-(N-benzylindol-3-ylmethylene)quinuclidin-3-ol derivatives as potent thermal sensitizing agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:6821–6824. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J, Cinar R, Liu J, Godlewski G, Wesley D, Jourdan T, Szanda G, Mukhopadhyay B, Chedester L, Liow JS, Innis RB, Cheng K, Rice KC, Deschamps JR, Chorvat RJ, McElroy JF, Kunos G. Peripheral cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonism reduces obesity by reversing leptin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;16:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. Withdrawal of Rimonabant--walking the tightrope of 21st century pharmaceutical regulation? Current drug safety. 2009;4:2–4. doi: 10.2174/157488609787354396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte D, Le Dorze JA, Esfahani F, Frost E, Gomori A, Namaka M. Examining the roles of cannabinoids in pain and other therapeutic indications: a review. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2010;11:17–31. doi: 10.1517/14656560903413534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal LF, Scheen AJ, Rissanen AM, Rossner S, Hanotin C, Ziegler O. Long-term effect of CB1 blockade with rimonabant on cardiometabolic risk factors: two year results from the RIO-Europe Study. Eur. Heart J. 2008 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle MD, Duncan M, Kingsley PJ, Mouihate A, Urbani P, Mackie K, Stella N, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D, Davison JS, Marnett LJ, Di Marzo V, Pittman QJ, Patel KD, Sharkey KA. Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science. 2005;310:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1115740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidinsky B, Gal P, Pilatova M, Vidova Z, Solar P, Varinska L, Ivanova L, Mojzis J. Anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic effects of CB2R agonist (JWH-133) in non-small lung cancer cells (A549) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells: an in vitro investigation. Folia Biol. (Praha) 2012;58:75–80. doi: 10.14712/fb2012058020075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargent ET, Zaibi MS, Silvestri C, Hislop DC, Stocker CJ, Stott CG, Guy GW, Duncan M, Di Marzo V, Cawthorne MA. The cannabinoid Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) ameliorates insulin sensitivity in two mouse models of obesity. Nutr. Diabetes. 2013;3:e68. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JL, Gentry KR, Dengler EC, Wallace JA, Kerwin AA, Armijo LM, Kuhn MN, Thakur GA, Makriyannis A, Milligan ED. Intrathecal cannabilactone CB(2)R agonist, AM1710, controls pathological pain and restores basal cytokine levels. Pain. 2012;153:1091–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Ingram SL, Henderson G, Chavkin C, von Zastrow M, Schulz S, Koch T, Evans CJ, Christie MJ. Regulation of mu-opioid receptors: desensitization, phosphorylation, internalization, and tolerance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013;65:223–254. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Peng XQ, Li X, Song R, Zhang HY, Liu QR, Yang HJ, Bi GH, Li J, Gardner EL. Brain cannabinoid CB receptors modulate cocaine's actions in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1160–1166. doi: 10.1038/nn.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue BG, Belluzzi JD, Stein L. In vitro reinforcement of hippocampal bursting by the cannabinoid receptor agonist (-)-CP-55,940. Brain Res. 1993;626:272–277. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90587-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Wang L, Xie XQ. Latest advances in novel cannabinoid CB(2) ligands for drug abuse and their therapeutic potential. Future medicinal chemistry. 2012;4:187–204. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]