Abstract

Importance

Patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) have an elevated (25%) risk for developing schizophrenia. Recent reports have suggested that a subgroup of children with 22q11DS display a substantial decline in cognitive abilities, starting at a young age.

Objective

To determine whether early cognitive decline is associated with risk of psychotic disorder in 22q11DS.

Design, setting and participants

As part of an international research consortium initiative, we used the largest dataset of intelligence (IQ) measurements in subjects with 22q11DS reported to date in order to investigate longitudinal IQ trajectories and the risk of subsequent psychotic illness. A total of 829 subjects with a confirmed hemizygous 22q11.2 deletion, recruited through 12 international clinical research sites, were included. Both psychiatric assessment and longitudinal IQ measurements were available for a subset of 411 subjects (388 with ≥1 assessment at age 8 to 24 years).

Main outcome measures

Diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, longitudinal IQ trajectory and initial IQ, as well as timing of the last psychiatric assessment with respect to the last IQ test.

Results

On average, children with 22q11DS showed a mild decline in full scale IQ (7 points) with increasing age, particularly in the domain of verbal IQ (9 points). In those who developed psychotic illness (47/388) this decline was significantly steeper (p<0.0001). Those with a negative deviation from the average cognitive trajectory observed in 22q11DS were at significantly increased risk for the development of a psychotic disorder (OR=2.49, 95% CI 1.24–5.00, p=0.01). The divergence of verbal IQ trajectories between those who subsequently developed a psychotic disorder and those who did not was distinguishable from the age of 11 years onwards.

Conclusions and relevance

In 22q11DS early cognitive decline is a robust indicator of the risk of developing a psychotic illness. These findings mirror those observed in idiopathic schizophrenia. The results provide further support for investigations of 22q11DS as a genetic model for elucidating neurobiological mechanisms underlying the development of psychosis.

Cognitive decline in schizophrenia is a fundamental component of the illness.1 Importantly, this decline is evident years prior to emergence of psychotic symptoms,2–11 indicating that the onset of the disease process precedes the emergence of overt symptoms.12 In clinical practice, psychosis is a necessary diagnostic criterion prompting initiation of treatment. The time lag between onset of the disease process and diagnosing schizophrenia is a major challenge for research into early phases of the disorder. Given the prevalence of schizophrenia (~1%), large samples are required to establish the association of early phenotypic changes with subsequent development of psychosis.

The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) offers a valuable model to study risk mechanisms for schizophrenia. Approximately 25% of patients with 22q11DS develop schizophrenia,13–16 making the associated hemizygous 1.2–3Mb deletion on the long arm of chromosome 2217,18 the strongest single genetic risk factor for the disorder.19 The core phenotype of schizophrenia in 22q11DS, including the neurocognitive profile, is similar to that of schizophrenia in the general population.20,21

22q11DS patients perform worse on neurocognitive tests such as verbal memory22 and spatial working memory23 after the onset of psychosis compared to those without psychosis. Psychotic disorder was associated with a deterioration of social and academic skills24 as well as a deficit of approximately eight intelligence quotient (IQ) points25 in cross-sectional studies, while previous longitudinal studies suggest that loss of cognitive skills, especially verbal IQ (VIQ), precedes the emergence of psychosis.26–28 Such findings are consistent with observations of schizophrenia in the general population.2–11,29 Although some decline relative to population norms – i.e. developmental lag - is expected in children in the lower IQ range,30–32 a recent prospective longitudinal study found that about one-third of children with 22q11DS under age 10 not only display cognitive deficit relative to age norms, but also an absolute decline in cognitive abilities.33 Collectively, these initial studies suggest that in patients with 22q11DS, as in the general population, both early cognitive deficits as well as early cognitive decline could portend schizophrenia.

This is the first multi-site study on the developmental trajectory of intellectual abilities and psychosis in 22q11DS, reporting the largest longitudinal dataset of subjects with 22q11DS to date. We hypothesized that cognitive decline observed in children and adolescents with 22q11DS is associated with subsequent onset of psychotic illness.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 829 subjects with 22q11DS was drawn from the International 22q11DS Brain Behavior Consortium, a collaboration of 22 research sites. Data include standardized cognitive and psychiatric assessment obtained from ongoing studies. Subjects were selected based on availability of: a) IQ measurements obtained with Wechsler intelligence scales (e.g. WPSSI, WISC, WASI or WAIS)34–37, and b) a structured diagnostic interview by a trained clinician.

Recruitment & assessment

Subjects were included in studies approved by the local IRB committees and with appropriate informed consent. Presence of the 22q11.2 deletion was confirmed by established genetic methods. eTables S1 – S3 present the sites, assessment methods and demographics. The total data for 829 subjects with 22q11DS generated cognitive development charts normative for 22q11DS; we use the term “22q11DS-specific” throughout this manuscript to distinguish these from norms derived from the general population. The association between IQ trajectory and psychotic disorder was examined in a subgroup of 388 subjects with longitudinal data (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of 22q11DS subjects’ selection steps.

No explanatory legend required.

Diagnostic categories

We defined psychotic disorder, here termed “psychosis”, as any psychotic spectrum disorder, including schizophrenia (n=20), schizoaffective (n=6), schizophreniform (n=3), brief psychotic disorder (n=2), delusional disorder (n=2), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (NOS; n=21) and bipolar I disorder with psychotic features (n=1). The relative timing of the most recent psychiatric assessment to the last cognitive measurement, pertinent to evaluating whether changes in IQ precede the onset of psychosis, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timing of psychiatric assessment relative to last cognitive assessment in 411 subjects with 22q11DS, and diagnostic classifications for the 55 subjects with psychosis.

| Timing of psychiatric diagnosis (DIAGN) versus timing of last cognitive assessment (COGN) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIAGN before last COGN1 | DIAGN at the same time or after last COGN1 | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| With psychosis (n=55) | 26 | 47.3 | 29 | 52.7 |

| Without psychosis (n=356) | 142 | 39.9 | 214 | 60.1 |

| All (n=411) | 168 | 40.9 | 243 | 59.1 |

| Diagnostic classification of psychotic disorders (according to DSM-IV criteria) | ||||

| n | % | |||

| Schizophrenia | 20 | 35.7 | ||

| Schizophreniform disorder | 3 | 5.5 | ||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 6 | 10.9 | ||

| Delusional disorder | 2 | 3.6 | ||

| Brief psychotic disorder | 2 | 3.6 | ||

| Psychotic disorder NOS | 21 | 38.2 | ||

| Bipolar I disorder (with prominent psychotic symptoms) | 1 | 1.8 | ||

| Total subjects “with psychosis” 2 | 55 | 100.0 | ||

DIAGN before last COGN: the most recent psychiatric assessment performed more than 3 months prior to the last cognitive assessment. DIAGN at the same time or after last COGN: the most recent psychiatric assessment was within 3 months before or after the last cognitive assessment, or at any time thereafter.

In one subject, who had been previously assessed in direct interviews, the presence of psychosis was subsequently reported by parents by telephone.

Statistical analysis

Because of the limited number of IQ measures in subjects <8 years and > 24 years, we restricted analyses to ages 8–24 years. We performed three analyses (Figure 1):

22q11DS-specific IQ-trajectory charts: IQ data from 829 subjects with 22q11DS (389 with one assessment, 440 with >=2 longitudinal assessments) yielded 1164 observations to construct 22q11DS-specific IQ-trajectories.

Cumulative IQ change curves: These analyses required data on psychiatric diagnosis and included a subset of 411 subjects with 22q11DS: 388 had at least two longitudinal IQ measurements, including one obtained between ages 8–24 years (341 without psychosis, 47 with psychosis at the most recent assessment).

Calculation of effect size for cognitive decline: This subsample included 326 subjects with at least two IQ measurements within the age range 8–24 years (281 without psychosis, 45 with psychosis).

For all analyses we used scaled IQ scores. Since the development and stability of cognitive abilities in 22q11DS patients deviates from the general population, we established a 22q11DS-specific chart for intellectual development in 22q11DS, similar to growth charts for patients with this38 and other syndromes.39 Individual IQ measurements were used to calculate percentiles for each age stratum. A four-year-bin sliding window was applied to enhance accuracy of percentile estimation. Subsequently, percentile points were connected to generate percentile lines, which were smoothed using the Bezier curve procedure (R script, Supplemental Material). Smoothing percentile lines is a standard procedure in the development of normative charts.40

Change in IQ per year was calculated as the difference in IQ between two measurements divided by the number of interval years. For each year (8–24) the mean annualized IQ change was calculated (1695 calculated observations, on average 100 per year, with a minimum of 19 such observations at 24 years). The mean delta IQ per year of these observations (calculated separately for full scale, verbal and performance IQ) was used to construct the cumulative IQ trajectory curves.

The cumulative trajectories of IQ change over time are represented separately for those with and without psychosis (Figures 3a–c). A bootstrap procedure evaluated at which point the 95% confidence intervals of the two curves no longer overlapped, indicating a significantly different trajectory of the slopes. We performed a regression analysis to estimate the change in IQ as a function of age, containing linear and quadratic expressions of age as regressors, and allowing full interaction with diagnostic status. Thus, we tested whether the rate of linear change differed between subjects with and without psychosis.

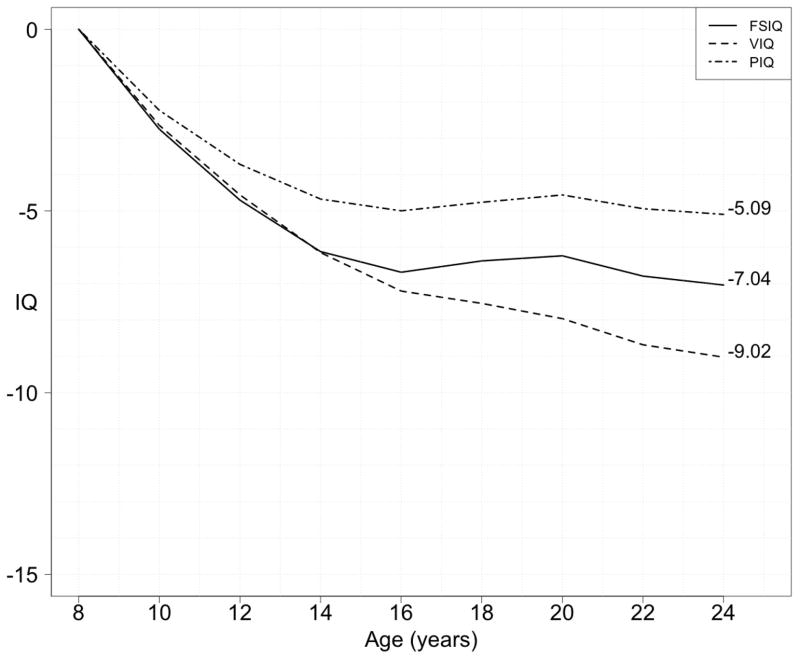

Fig. 3a–c. Cumulative plot of the mean annual IQ decline per age (Verbal, Performance and Full Scale) in 22q11DS, with psychosis vs. without psychosis.

For each year the average change in IQ is calculated and represented cumulatively for both subgroups (subjects with 22q11DS with and those without a psychotic disorder) where two or more IQ test results were available between ages 8 and 24 years (n=388). Note that this graph is not a longitudinal “average” trajectory. This implies that the effect size of IQ decline between the two groups is not calculated by the absolute difference in IQ at any given age, but by the difference in slope. What can be observed is that in the subjects in whom a psychotic disorder is diagnosed the decline in IQ is steeper for most age points (p<0.001), but most pronounced for VIQ as illustrated by the larger effect size (partial Eta squared of 0.07 for VIQ, 0.04 for FSIQ and 0.01 for PIQ).

Next, we examined the strength of correlation between IQ decline and psychosis risk using the 22q11DS-specific chart of average IQ trajectory. We considered the difference in IQ percentile between two time points as a categorical variable comparing those with negative deviations from the original percentile versus those with no change or increase from the original percentile. Subsequently, the proportion of subjects with psychosis was compared between those with and without IQ decline according to these categorical definitions. We used logistic regression analyses with psychosis as the primary outcome measure and IQ percentile decline as the dependent variable. Age at last assessment and gender were covariates. Next, IQ at the first measurement was added to the model as a continuous variable (and post-hoc as a dichotomized variable using a median split). Finally, we examined to what extent the timing of the most recent psychiatric assessment relative to the last cognitive measurement could have influenced the results. We performed a post-hoc analysis with the time between the last IQ measurement and the time of psychiatric assessment as a covariate in the logistic regression model.

Results

The mean age at the most recent psychiatric assessment in subjects with at least 2 IQ measurements (n=411, Figure 1) was 16.1 (± SD 6.2) years. The male to female ratio was 0.9:1 and 55/411 subjects (13.4%) were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. Baseline IQ (i.e. IQ at first cognitive assessment) was lower in this group (FSIQ 65.5 (± SD 12.0), VIQ 67.5 (± SD 14.7), PIQ 65.0 (± SD 16.9)) compared to those without a psychotic disorder (FSIQ 74.0 (± SD 14.0), VIQ 74.8 (± SD 18.6), PIQ 71.8 (± SD 16.6)). Overall, subjects showed a decline in IQ over time, particularly in VIQ. The average total declines in cognitive abilities (ages 8–24) were 7.0 points (FSIQ), 9.0 points (VIQ) and 5.1 points (PIQ) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Cumulative plot of the mean annual IQ decline per age in 22q11DS (full longitudinal sample, Verbal, Performance and Full Scale).

For each year the average change in IQ is calculated and represented cumulatively for FSIQ, VIQ and PIQ for all 22q11DS subjects where two or more IQ test results were available between ages 8 and 24 years (n=388). Note that this graph is not a longitudinal “average” trajectory.

There was a significant difference in the slope of IQ trajectories; the psychosis group demonstrated a steeper decline than the non-psychosis group (Figure 3a–c). The difference was significant for FSIQ and both subscales (p-values < 0.001), but was most pronounced for VIQ as illustrated by the larger effect size (partial Eta squared of 0.07 for VIQ, 0.04 for FSIQ and 0.01 for PIQ). The divergence of VIQ trajectories started early (Figure 3a), with the 95% CIs of the VIQ trajectories for the two groups calculated with the bootstrap procedure not overlapping from age 11 onward. Notably, the average age at onset of the first psychosis, estimated from the available clinical records, was 18.1 yrs (95% confidence intervals 17.0 – 19.1 yrs) with the youngest age at onset being 12.7 years.

The average age at psychiatric assessment differed between the non-psychosis (15.5±5.8 yrs.) and psychosis groups (20.1±7.5 yrs.; p<0.001). Importantly, the average age at last cognitive assessment followed a similar pattern (16.3±5.7 and 22.2±9.3 yrs., respectively). To examine whether a change in IQ precedes the onset of psychosis, the last cognitive assessment should be performed before the psychiatric assessment. In our sample, both order and interval between the two assessments was variable. However, the proportion of 22q11DS subjects for whom their last psychiatric assessment preceded their last cognitive assessment was comparable between those with (47.3%) and those without psychosis (39.9%) (p=0.37, Table 1).

eFigures S1a–c present 22q11DS-specific charts for the trajectory of intellectual development. Overall, there is a mild decrease in IQ between ages 8 and 24 years. From age 20 onwards the number of available observations dropped substantially, limiting the accuracy of percentile trajectories.

Although all IQ slopes (FSIQ, VIQ, PIQ) differed significantly between the two 22q11DS groups, the most pronounced deviation in trajectory between those with and without psychosis was in VIQ. We therefore further examined this measure. Using the 22q11DS-specific chart, for each subject we assessed whether the results of the second VIQ measurement were consistent with or changed from the initial VIQ percentile. eFigure S2 shows a histogram of the distribution of deviations from VIQ percentile; the curve is skewed to the left and the subgroup with psychosis is over-represented in the negative range. We therefore defined cognitive decline as a negative deviation from the trajectory expected in 22q11DS subjects.

Comparing those with and without a decline in VIQ, we found that subjects with VIQ decline were more likely to develop a psychotic illness (Table 2: 18.2% vs. 9.8%; OR=2.49, 95% CI 1.24–5.00, p=0.010) We then examined to what extent low IQ at the first measurement could be a risk factor for psychosis. When added to the model, both initial VIQ and the VIQ decline were significantly associated with an increased risk for psychosis (OR=3.89, 95% CI 1.73–8.75 for decline, p=0.001). When initial IQ measurements alone were considered only FSIQ at initial measurement was significantly associated with subsequent psychotic illness (p=0.005).

Table 2.

Effect size of IQ decline with respect to diagnosis of a psychotic disorder in 22q11DS

| Model | Predictors in model | VIQ | PIQ | FSIQ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | ||

| I | IQ decline | 2.49 | 0.010 | 1.14 | 0.70 | 1.14 | 0.70 |

| II | IQ decline | 3.89 | 0.001 | 1.52 | 0.29 | 1.86 | 0.11 |

| Initial IQ, dimensional | 0.97 | 0.006 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.001 | |

| III | Initial IQ, dimensional | 0.99 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 0.96 | 0.005 |

| IV | Initial IQ <75 vs >=75 | 1.95 | 0.07 | 1.18 | 0.65 | 2.73 | 0.008 |

Effect size (in Odd’s Ratio, OR) and corresponding p-values for logistic regression models with psychosis as the primary outcome and age at last IQ measurement and gender as covariates. For each model the predictors are given in column 2. Significant results (p-value < 0.05) are highlighted in bold. Note that in models II and III the initial IQ was examined as a continuous measure, therefore the associated ORs reflect the effect size per IQ point change. In models III and IV the age at initial IQ measurement was used as a covariate instead of age at last IQ measurement.

Given this observation, we examined initial IQ as a dichotomous variable in a post-hoc analysis, using a definition of potential clinical value. We found that regardless of subsequent decline, baseline FSIQ above 75 was associated with lower risk for developing psychosis (OR=2.73, 95% CI 1.30–5.73, p=0.008). We assessed the possible influence of the time interval between psychiatric and cognitive measurements, covarying for this interval in the logistic regression model. The findings maintained, indicating that the difference in IQ trajectories between those with and without psychosis could not wholly be attributed to variation of the time interval between the last cognitive and psychiatric assessments (data not shown). Also, when restricting the analysis to the subgroup of subjects in whom the psychiatric assessment either co-occurred or followed the last cognitive measurement (see Table 1) the results were similar (difference in VIQ trajectories between those with and those without psychosis: OR=2.56, p=0.026).

Discussion

In the largest study ever conducted of the developmental trajectory of intellectual abilities in 22q11DS, we found that cognitive decline in subjects with 22q11DS is greater in those who develop a psychotic disorder, and this decline appears to start as early as age 11. Those with a negative deviation from the average cognitive trajectory observed in 22q11DS had a three-fold increased risk for the development of a psychotic disorder. This is further support that 22q11DS provides a unique opportunity to prospectively examine the pathophysiology of cognitive decline preceding the onset of psychosis.

Our results also suggest that cognitive decline could potentially become a useful marker in the clinical management of youth with 22q11DS. Several studies have reported potential markers for psychosis in 22q11DS, including changes in brain anatomy,26,27,41–43 high plasma levels of the amino acid proline44–46 and genetic variation at the intact 22q11.2 allele.47–49 These markers however may be difficult to implement clinically, due to practical constraints and/or small effect sizes. Serial cognitive testing in 22q11DS is feasible in clinical practice33 and the effect sizes reported here may be clinically meaningful. Although independent replication and an understanding of the predictive values of cognitive change at the individual level are needed, our findings suggest the potential utility of implementing a systematic surveillance of cognitive development in current clinical practice.

Our findings indicate that, regardless of subsequent decline, a relatively low initial IQ (below 75) measured at or before the onset of adolescence is, independently, a risk factor for psychosis in 22q11DS. This finding is consistent with studies in the general population indicating that low IQ increases the risk for schizophrenia8,50 and that this cognitive deficit is already apparent by age 13, years before the typical onset of psychosis.51,52

The study of cognition associated with schizophrenia (risk) encompasses different concepts,53 including early developmental deficits that may remain stable over time, and deficits that emerge during development. Decline observed in cognitive performance may be due to the phenomenon of developmental lag where the cognitive growth is insufficient to keep up with the development observed in normal peers. Alternatively, cognitive decline may also represent an absolute loss of previously acquired cognitive ability. The underlying mechanism of the cognitive decline observed in the current study cannot be determined and could therefore be related to developmental lag, absolute decline, or both. A previous study of 22q11DS subjects indicates that an absolute loss of cognitive abilities is likely to contribute to the observed decline.33

Possibly, low initial IQ and subsequent cognitive decline are two independent phenomena, with the former reflecting suboptimal neurodevelopment leading to brain vulnerability to a broad range of psychopathology. Indeed, in the general population low IQ increases the risk for many neuropsychiatric disorders.50,54–56 Consistently, subjects with 22q11DS have, on average, lower cognitive abilities compared to the general population and display a wide range of psychiatric disorders.16,57,58 Early cognitive decline may reflect a distinct process in this genetic condition, that may be specifically associated with the ensuing psychotic disorder. The nature of the association between psychosis and low or decline in IQ cannot be inferred from our observations however. It is possible that a deficit and/or decline in cognitive abilities render the brain vulnerable to psychosis. Alternatively, both IQ changes and psychosis may be manifestations of the same mechanism. Findings from the Dunedin birth cohort indicate that both a baseline cognitive deficit, measured at age 7, and a subsequent developmental lag in cognitive performance (particularly in domains indexing rapid information-processing) between 7 and 13 years are associated with increased risk for idiopathic schizophrenia.53 Our results are largely consistent with these observations, although in contrast to findings in 22q11DS patients,59 in the Dunedin cohort no evidence was found for absolute cognitive deterioration.53 Alternatively, it is possible that some subjects with low initial IQ in our sample may have had IQ decline prior to the first cognitive measurement. Indeed, cognitive decline in 22q11DS has been observed between the ages of 5.5 and 9.5 years,33 and approximately one third of patients who show stable IQ after age 9.5 years have shown a decline in cognitive abilities between 7.5 and 9.5 years.60 The apparent stabilization of the IQ trajectory between ages 16–20 years observed in our study (Figures 2, 3) may suggest that IQ decline before age 16 is prodromal while further decline after age 18–20 may be related to further cognitive deterioration associated with the emergence of psychosis itself and diminishing cognitive reserve.61

Several features make 22q11DS a unique model to study schizophrenia developmentally, particularly “the trajectory from risk to disorder”.62 In 22q11DS we have both a high risk for psychotic disorders, especially schizophrenia, caused by a specific genetic etiology, and the frequent identification of this etiology very early in life thus allowing follow-up across the lifespan. The occurrence of cognitive decline prior to the first psychotic episode1,6,63, observed in both 22q11DS and idiopathic schizophrenia, strongly suggests that psychosis is likely a late symptom of the disease. To increase our understanding of schizophrenia, more efforts should be directed towards elucidation of its early cognitive aspects.12 The study of patients with 22q11DS provides a valuable contribution to this endeavor.

In particular, one or more genes within the deletion region or elsewhere in the genome may be involved in the etiology of both early cognitive decline and the ensuing expression of schizophrenia. The relative genetic homogeneity and the high risk of expression of these phenotypes in the 22q11DS population contrast with the general population where genetic contributions to schizophrenia are highly heterogeneous and risk is much lower. Therefore, studying 22q11DS as a genetic model for these phenotypes may facilitate the identification of contributing genes. Arguably such genes may also be involved in the etiology of cognitive decline and schizophrenia in the general population.

The study has several limitations. A priori standardization of cognitive and psychiatric assessment methods across sites is lacking; however in all subjects the diagnosis of psychotic disorders was determined using the same (DSM-IV) classification criteria. Moreover, our cognitive data were restricted to those assessed with any of the Wechsler scales to optimize comparison over time and across sites. Timing of the psychiatric assessment in relation to last IQ testing is critical for discerning whether changes in IQ precede psychosis onset. In our dataset the sequence was variable; however in 59% of subjects the psychiatric assessment was performed either concurrently or after the last cognitive assessment. This proportion was not different between those with and without psychosis. Importantly, the observed association between cognitive decline and psychosis did not change after inclusion of the time interval between psychiatric and cognitive assessment as a covariate. Furthermore, the average estimated age at onset of psychosis was 18.1 years, 95% CI 17.0–19.1, much later than the age at which the divergence of IQ appears (Figure 3a).

In this dataset the best estimate of psychosis onset was the time of the psychiatric assessment at which the diagnosis was made. The actual age at onset may differ as a function of the delay between the onset of symptoms and the psychiatric evaluation. However, 22q11DS patients, given the awareness of the genetically mediated increased risk for psychotic disorders, may tend to present for evaluation as soon as behavioral changes emerge. Nevertheless, more accurate data on the actual age at onset of psychosis, and possibly the use of continuous measures of psychosis, will be valuable for future studies in this population. Another limitation is insufficient data to estimate IQ changes beyond age 24, although there is evidence suggesting further cognitive decline in some adults with 22q11DS.64 Ongoing data collection in several 22q11DS cohorts will provide such information. Finally, no information was available regarding socioeconomic status of the subjects.

In many subjects the last psychiatric assessment was performed at a rather young age, therefore some children currently without a psychotic disorder diagnosis may later develop psychosis. Ideally, the groups with and without psychosis should be matched for age. Restricting the sample to age-matched subjects was not feasible due to insufficient power. We therefore used age as a covariate in our analyses. Previous studies indicate that approximately 25% of patients with 22q11DS develop schizophrenia. In the present study only 13.4% had psychosis, and thus a substantial proportion of subjects currently classified as “without psychosis” may be, in reality, false negatives. However, as a consequence, the IQ trajectory in the “without psychosis” group would be expected to show less decline than that observed. Thus, our data are likely to represent a conservative portrayal of the divergent IQ trajectories in 22q11DS patients with and without psychosis.

Although our analyses were restricted to subjects assessed with Wechsler scales, in some subjects different versions were used. Possibly, those subjects, in particular when a change occurred from WISC-III to WAIS, may demonstrate a change in IQ score resulting from different normative comparison groups between the two versions. Available evidence suggests that in comparison to the WISC, the WAIS tends to result in somewhat higher IQ scores65. Therefore, if the use of different Wechsler scales has influenced our results in any way, the changes from WISC to WAIS would be expected to mitigate the overall observed average decline in IQ in our 22q11DS patients, rather than to exaggerate it. Importantly, the proportion of subjects in whom such a shift in test version occurred at follow-up was similar in the “with psychosis” (27%) and “without psychosis”(25%) subgroups, making this unlikely to explain the observed difference in IQ trajectories. Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study is unprecedented in the large size of the cohort, the prospective design and the restriction to one type of intelligence assessment.

Conclusion

Subjects with 22q11DS who develop psychotic disorder show a significant cognitive decline, most pronounced in verbal IQ. This decline is significantly steeper than the intellectual decline over childhood and adolescence observed in 22q11DS subjects without psychosis. Importantly, the IQ trajectories in those with and without a psychotic disorder diverge at an early age, several years before the usual onset of psychosis in 22q11DS.16,20,28 Our observations have potential ramifications for clinical management of 22q11DS patients and for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, especially the importance of early cognitive decline preceding the first psychotic episode.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figures S1a–c: 22q11DS-specific IQ trajectories (n=829)

Supplemental Figure S2 Histogram of VIQ percentile changes from one time point to the next in in 326 subjects with 22q11DS

A histogram showing the distribution of changes in percentile between two sequential VIQ measurements. Note that the top of the curve is in the negative range of percentile change, consistent with a slight overall decline observed in the 22q11DS population. The grey shaded area represents the subset of 45 subjects with 22q11DS with a psychotic disorder.

Supplemental Table S1: participating sites and total sample sizes of subjects with 22q11.2DS with IQ data in this study

Supplemental Table S2: Sample demographics & assessment methods for 411 subjects with 22q11DS aged 8 – 24 years with IQ and psychiatric data.

Supplemental Table S3: Number and type of Wechsler IQ scales used per site in n = 411 subjects with 22q11DS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NIMH International Consortium on Brain and Behavior in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome; the Swiss National Fund to Dr. Eliez (grants PP00B_102864 and 32473B_121996); the National Center of Competence in Research program Synapsy, financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation, to Dr. Eliez (grant 51AU40_125759); the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Drs. Bassett and Chow (grants MOP-97800, MOP-89066, and MOP-74631); the Ontario Mental Health Foundation to Dr. Chow; support of Dr. Bassett as the Canada Research Chair in Schizophrenia Genetics and Genomic Disorders and as the Dalglish Chair in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome; the Baily Thomas Charitable Trust to Drs. van den Bree (grant 2315/1); the Waterloo Foundation to Drs. van den Bree (grant 912- 1234); the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund to Drs. van den Bree; Ireland’s Health Research Board to Dr. K.C. Murphy (grants RP/2004/30 and RP/2008/169); the Health Foundation to Drs. K.C. Murphy (grant 1206/188); NIMH to Dr. Kates (grant MH-064824 and MH-065481), Dr. Gur (grant MH-087626), Drs. McDonald-McGinn and Zackai (grant MH-087636), Dr. Shashi (grants MH-078015 and MH-091314), Dr. Bearden (grant RO1 MH-085953 and R01 HD065280), and Drs. van den Bree, Arango, D.G. Murphy and K.C. Murphy (grant 1U01MH101724-01); the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to Drs. McDonald-McGinn and Zackai (grant HD-070454), Dr. Bearden (P50 HD-055784 [CART pilot project grant]), and Dr. Simon (grant R01 HD-042974); the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD) to Dr. Vorstman (Young Investigator Award), Dr. Van Amelsvoort (Young Investigator Award), Dr. Armando (Young Investigator Award), and Dr. Ousley; the State University of New York Hendricks Fund to Dr. Antshel; the Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Research Award by the March of Dimes to Dr. Gothelf (grant 5-FY06-590); the Binational Science Foundation to Dr. Gothelf (grant 2011378); the Gazit-Globe Award to Dr. Green; the Dutch Brain Foundation to Dr. Van Amelsvoort; the Robert W. Woodruff Fund to Dr. Ousley; the Simons Foundation to Dr. Ousley; a Hunter Medical Research Institute Post-Doctoral Fellowship to Dr. Campbell; and an Australian Training Fellowship awarded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia to Dr. Simon (grant 455614).

Group authorship:

Beverly S Emanuel, PhD: Department of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, 3615 Civic Center Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States.

Elaine H Zackai, MD: Division of Human Genetics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.

Leila Kushan, M.Sc., Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, 300 Medical Plaza, Suite 2265; Los Angeles, CA 90095; United States.

Wanda Fremont, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, State University of New York at Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York, United States.

Kelly Schoch, MS: Department of Pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, United States.

Joel Stoddard, MD: MIND Institute and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, Davis, United States.

Joseph Cubells: Emory University School of Medicine, Emory Autism Center, Department of Human Genetics and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 1551 Shoup Court, 30322 Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

Fiona Fu, Clinical Genetics Research Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Linda E Campbell, PhD. School of Psychology, Ourimbah, University of Newcastle and the Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia.

Rosemarie Fritsch; Department of Psychiatry, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Chile, Santiago

Elfi Vergaelen MD: Center for Human Genetics, KU Leuven, Belgium

Marjolein Neeleman, MD: Department of Psychiatry, Brain Center Rudolf Magnus, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Erik Boot MD, PhD: Department of Nuclear Medicine, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Martin Debbané, PhD; Office Médico-Pédagogique Research Unit, Department of Psychiatry, University of Geneva School of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland.

Nicole Philip, MD, Aix-Marseille Université, UMR-S910 and APHM, Département de Génétique Médicale Hôpital d’Enfants de la Timone, Marseille, France

Tamar Green, M.D. The Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California and Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Marianne BM van den Bree, PhD; MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Institute of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

Declan Murphy, MD; Sackler Institute for Translational Neurodevelopment and Department of Forensic and Neurodevelopmental Sciences, King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London, United Kingdom.

Jaume Morey, MD, PhD; Canyelles, Balearic Institute of Child and Adolescent Mental Helath, Son Espases University Hospital, Mallorca, Spain.

Celso Arango, MD, PhD; Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, IiSGM, School of medicine, Universidad Complutense, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain.

Kieran C Murphy MD PhD; Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland

Maria Pontillo, PhD; Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, Rome

Footnotes

Author contributions

Drs Vorstman, Breetvelt and Bassett had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Vorstman and Breetvelt contributed equally to the study. Study concept and design: Vorstman, Breetvelt, Duijff, Kahn, Swillen, Bearden, Gur, Bassett. Acquisition of data: Vorstman, Duijff, Eliez, Schneider, Jalbrzikowski, Armando, Vicari, Shashi, Hooper, Chow, Fung, Butcher, Young, McDonald-McGinn, Vogels, Gothelf, Weinberger, Weizman, Klaassen, Koops, van Amelsvoort, Kates, Antshel, Simon, Ousley, Swillen, Gur, Bearden, Bassett. Analysis and interpretation of data: Vorstman, Breetvelt, Duijff, Kahn, Swillen, Bearden, Gur, Bassett. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Breetvelt, Vorstman

Conflict of interest disclosures

Stephen R. Hooper has provided consultation to Novartis. Opal Ousley is a collaborator in a Biomarin Pharmaceutical study. None of the other authors have declared a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kraepelin E. In: Dementia praecox and paraphrenia (1919) Barclay RM, translator; Robertson GM, editor. New York: Robert E. Krieger; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Rapp MA, et al. Elaboration on premorbid intellectual performance in schizophrenia: premorbid intellectual decline and risk for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1297–1304. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon TD, Bearden CE, Hollister JM, Rosso IM, Sanchez LE, Hadley T. Childhood cognitive functioning in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected siblings: a prospective cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):379–393. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bearden CE, Rosso IM, Hollister JM, Sanchez LE, Hadley T, Cannon TD. A prospective cohort study of childhood behavioral deviance and language abnormalities as predictors of adult schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):395–410. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(5):449–456. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller R, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, O’Leary D, Ho BC, Andreasen NC. Longitudinal assessment of premorbid cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia through examination of standardized scholastic test performance. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(7):1183–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinowitz J, De Smedt G, Harvey PD, Davidson M. Relationship between premorbid functioning and symptom severity as assessed at first episode of psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2021–2026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(5):579–587. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keefe RS, Perkins DO, Gu H, Zipursky RB, Christensen BK, Lieberman JA. A longitudinal study of neurocognitive function in individuals at-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2006;88(1–3):26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosway R, Byrne M, Clafferty R, et al. Neuropsychological change in young people at high risk for schizophrenia: results from the first two neuropsychological assessments of the Edinburgh High Risk Study. Psychol Med. 2000;30(5):1111–1121. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier MH, Caspi A, Reichenberg A, et al. Neuropsychological decline in schizophrenia from the premorbid to the postonset period: evidence from a population–representative longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(1):91–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn RS, Keefe RS. Schizophrenia Is a Cognitive Illness: Time for a Change in Focus. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy KC, Jones LA, Owen MJ. High rates of schizophrenia in adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):940–945. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg R, Golding-Kushner KJ, Marion RW. Late-onset psychosis in the velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42(1):141–142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vorstman JA, Morcus ME, Duijff SN, et al. The 22q11.2 deletion in children: high rate of autistic disorders and early onset of psychotic symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1104–1113. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000228131.56956.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider M, Debbane M, Bassett AS, et al. Psychiatric Disorders From Childhood to Adulthood in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome: Results From the International Consortium on Brain and Behavior in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edelmann L, Pandita RK, Spiteri E, et al. A common molecular basis for rearrangement disorders on chromosome 22q11. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(7):1157–1167. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaikh TH, Kurahashi H, Saitta SC, et al. Chromosome 22-specific low copy repeats and the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: genomic organization and deletion endpoint analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(4):489–501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karayiorgou M, Simon TJ, Gogos JA. 22q11.2 microdeletions: linking DNA structural variation to brain dysfunction and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(6):402–416. doi: 10.1038/nrn2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassett AS, Chow EW, AbdelMalik P, Gheorghiu M, Husted J, Weksberg R. The schizophrenia phenotype in 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1580–1586. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chow EW, Watson M, Young DA, Bassett AS. Neurocognitive profile in 22q11 deletion syndrome and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;87(1–3):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow EW, Watson M, Young DA, Bassett AS. Neurocognitive profile in 22q11 deletion syndrome and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;87(1–3):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Amelsvoort T, Henry J, Morris R, et al. Cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(2–3):223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuen T, Chow EW, Silversides CK, Bassett AS. Premorbid adjustment and schizophrenia in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Schizophr Res. 2013;151(1–3):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green T, Gothelf D, Glaser B, et al. Psychiatric disorders and intellectual functioning throughout development in velocardiofacial (22q11.2 deletion) syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1060–1068. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gothelf D, Eliez S, Thompson T, et al. COMT genotype predicts longitudinal cognitive decline and psychosis in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1500–1502. doi: 10.1038/nn1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kates WR, Antshel KM, Faraone SV, et al. Neuroanatomic predictors to prodromal psychosis in velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome): a longitudinal study. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(10):945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gothelf D, Schneider M, Green T, et al. Risk factors and the evolution of psychosis in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a longitudinal 2-site study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(11):1192–1203. e1193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane EA, Albee GW. On childhood intellectual decline of adult schizophrenics: a reassessment of an earlier study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1968;73(2):174–177. doi: 10.1037/h0020119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bos K. Relationship Between Cognitive Development, Decoding Skill, and Reading Comprehension in Learning-Disabled Dutch Children. In: Aaron PG, Joshi RM, editors. Reading and Writing Disorders in Different Orthographic Systems. Vol. 52. Springer Netherlands; 1989. pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Share DL, Silva PA. Language deficits and specific reading retardation: cause or effect? Br J Disord Commun. 1987;22(3):219–226. doi: 10.3109/13682828709019864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaywitz BA, Holford, Theodore R, Holahan John M, Fletcher Jack M, Stuebing Karla K, Francis David J, Shaywitz Sally E. A Matthew effect for IQ but not for reading: Results from a longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly. 1995;30(4):894–906. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duijff SN, Klaassen PW, de Veye HF, Beemer FA, Sinnema G, Vorstman JA. Cognitive development in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(6):462–468. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wechsler D. The Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 3. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wechsler D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Third Edition (WPPSI – III) San Antonio, TX: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wechsler D. The Wechsler intelligence scale for children - fourth edition (WISC-IV) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Habel A, McGinn MJ, 2nd, Zackai EH, Unanue N, McDonald-McGinn DM. Syndrome-specific growth charts for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in Caucasian children. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(11):2665–2671. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myrelid A, Gustafsson J, Ollars B, Anneren G. Growth charts for Down’s syndrome from birth to 18 years of age. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(2):97–103. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Buuren S, Fredriks M. Worm plot: a simple diagnostic device for modelling growth reference curves. Stat Med. 2001;20(8):1259–1277. doi: 10.1002/sim.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaer M, Debbane M, Bach Cuadra M, et al. Deviant trajectories of cortical maturation in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS): a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Schizophr Res. 2009;115(2–3):182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chow EW, Ho A, Wei C, Voormolen EH, Crawley AP, Bassett AS. Association of schizophrenia in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and gray matter volumetric deficits in the superior temporal gyrus. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):522–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10081230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.da Silva Alves F, Schmitz N, Bloemen O, et al. White matter abnormalities in adults with 22q11 deletion syndrome with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raux G, Bumsel E, Hecketsweiler B, et al. Involvement of hyperprolinemia in cognitive and psychiatric features of the 22q11 deletion syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(1):83–91. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vorstman JA, Turetsky BI, Sijmens-Morcus ME, et al. Proline affects brain function in 22q11DS children with the low activity COMT 158 allele. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(3):739–746. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magnee MJ, Lamme VA, de Sain-van der Velden MG, Vorstman JA, Kemner C. Proline and COMT status affect visual connectivity in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams NM, Glaser B, Norton N, et al. Strong evidence that GNB1L is associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(4):555–566. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vorstman JA, Chow EW, Ophoff RA, et al. Association of the PIK4CA schizophrenia-susceptibility gene in adults with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B(3):430–433. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gothelf D, Feinstein C, Thompson T, et al. Risk factors for the emergence of psychotic disorders in adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4):663–669. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zammit S, Allebeck P, David AS, et al. A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ Score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other nonaffective psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):354–360. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dickson H, Laurens KR, Cullen AE, Hodgins S. Meta-analyses of cognitive and motor function in youth aged 16 years and younger who subsequently develop schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2012;42(4):743–755. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Oel CJ, Sitskoorn MM, Cremer MP, Kahn RS. School performance as a premorbid marker for schizophrenia: a twin study. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(3):401–414. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reichenberg A, Caspi A, Harrington H, et al. Static and dynamic cognitive deficits in childhood preceding adult schizophrenia: a 30-year study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):160–169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dekker MC, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(8):1087–1098. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Roberts AL, et al. Childhood IQ and adult mental disorders: a test of the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(1):50–57. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gale CR, Deary IJ, Boyle SH, Barefoot J, Mortensen LH, Batty GD. Cognitive ability in early adulthood and risk of 5 specific psychiatric disorders in middle age: the Vietnam experience study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1410–1418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker K, Vorstman JA. Is there a core neuropsychiatric phenotype in 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome? Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25(2):131–137. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328352dd58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang SX, Yi JJ, Calkins ME, et al. Psychiatric disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome are prevalent but undertreated. Psychol Med. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duijff SN, Klaassen PW, de Veye HF, Beemer FA, Sinnema G, Vorstman JA. Cognitive development in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(6):462–468. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duijff SN, Klaassen PW, Swanenburg de Veye HF, Beemer FA, Sinnema G, Vorstman JA. Cognitive and behavioral trajectories in 22q11DS from childhood into adolescence: A prospective 6-year follow-up study. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(9):2937–2945. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hedman AM, van Haren NE, van Baal CG, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. IQ change over time in schizophrenia and healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1–3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pukrop R, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Klosterkotter J. Neurocognitive indicators for a conversion to psychosis: comparison of patients in a potentially initial prodromal state who did or did not convert to a psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2007;92(1–3):116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evers LJ, van Amelsvoort TA, Candel MJ, Boer H, Engelen JJ, Curfs LM. Psychopathology in adults with 22q11 deletion syndrome and moderate and severe intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jir.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaufman AS, Lichtenberger OL. Assessing Adolescent and Adult Intelligence. 3. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States of America: John Whiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figures S1a–c: 22q11DS-specific IQ trajectories (n=829)

Supplemental Figure S2 Histogram of VIQ percentile changes from one time point to the next in in 326 subjects with 22q11DS

A histogram showing the distribution of changes in percentile between two sequential VIQ measurements. Note that the top of the curve is in the negative range of percentile change, consistent with a slight overall decline observed in the 22q11DS population. The grey shaded area represents the subset of 45 subjects with 22q11DS with a psychotic disorder.

Supplemental Table S1: participating sites and total sample sizes of subjects with 22q11.2DS with IQ data in this study

Supplemental Table S2: Sample demographics & assessment methods for 411 subjects with 22q11DS aged 8 – 24 years with IQ and psychiatric data.

Supplemental Table S3: Number and type of Wechsler IQ scales used per site in n = 411 subjects with 22q11DS.