Abstract

The pharmacological effects of the anesthetic alfaxalone were evaluated after intramuscular (IM) administration to 6 healthy beagle dogs. The dogs received three IM doses each of alfaxalone at increasing dose rates of 5 mg/kg (IM5), 7.5 mg/kg (IM7.5) and 10 mg/kg (IM10) every other day. Anesthetic effect was subjectively evaluated by using an ordinal scoring system to determine the degree of neuro-depression and the quality of anesthetic induction and recovery from anesthesia. Cardiorespiratory variables were measured using noninvasive methods. Alfaxalone administered IM produced dose-dependent neuro-depression and lateral recumbency (i.e., 36 ± 28 min, 87 ± 26 min and 115 ± 29 min after the IM5, IM7.5 and IM10 treatments, respectively). The endotracheal tube was tolerated in all dogs for 46 ± 20 and 58 ± 21 min after the IM7.5 and IM10 treatments, respectively. It was not possible to place endotracheal tubes in 5 of the 6 dogs after the IM5 treatment. Most cardiorespiratory variables remained within clinically acceptable ranges, but hypoxemia was observed by pulse oximetry for 5 to 10 min in 2 dogs receiving the IM10 treatment. Dose-dependent decreases in rectal temperature, respiratory rate and arterial blood pressure also occurred. The quality of recovery was considered satisfactory in all dogs receiving each treatment; all the dog exhibited transient muscular tremors and staggering gait. In conclusion, IM alfaxalone produced a dose-dependent anesthetic effect with relatively mild cardiorespiratory depression in dogs. However, hypoxemia may occur at higher IM doses of alfaxalone.

Keywords: alfaxalone, anesthetic effect, canine, intramuscular

Injectable anesthetic agents as well as inhalation agents are useful for general anesthesia. However, intravenous (IV) administration of injectable agents or mask induction with inhalants is usually difficult and/or impossible in fractious, fearful or excited patients. Chamber induction with inhalant anesthetics might be useful in small veterinary patients, but it requires a massive container for large-breed dogs and is still associated with disadvantages, such as airway irritation and stress, in patients during the induction phase [28] and the waste gas pollution created [13]. Thus, the agents that can be administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly (IM) are very important for sedation or induction for general anesthesia in order to reduce the stress of handling and the risk of injury to both dogs and handlers.

Because of their availability and efficacy, IM administration of ketamine, opioids, α2-adrenoceptor agonists or their combinations [17, 20, 25, 32, 38, 40] has been widely used for sedation or general anesthesia in dogs. However, ketamine has been designated as a legally controlled drug, and its usage has been severely restricted in many countries. Ketamine also causes pain upon injection. In addition, α2-adrenoceptor agonists should be avoided in dogs with significant disease and/or aging, because they induce dose-dependent peripheral vasoconstriction and cardiovascular depression through reduced cardiac output and blood perfusion [6]. Therefore, it is very important to develop a new anesthetic agent that produces an anesthetic effect with minimal cardiorespiratory depression by an IM route of administration in dogs.

Alfaxalone (3-alpha-hydroxy-5-alpha-pregnane-11, 20-dione) is a synthetic neuroactive steroid molecule that modulates the gamma-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA) receptor and causes neuro-depression and muscular relaxation [1, 10, 21]. Because of its water insolubility, previous alfaxalone products (e.g., Althesin®, Saffan®) have been solubilized with 20% polyoxyethylated castor oil (Cremophor EL) and coformulated with a related neurosteroid, alfadolone. However, this product was voluntary withdrawn from the market, because of its side effects induced by histamine release associated with the solubilizing agent, such as hyperemia of the ear pinnae or forepaw in cats [8] and histamine-induced anaphylactoid reaction in dogs [5].

Recently, alfaxalone was reformulated with another solubilizing agent, 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPCD), which does not cause histamine release [3]. This formulation is approved in some countries (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Korea, Japan, U.S.A. and Canada) as an IV anesthetic agent in dogs and cats. Intravenous administration of alfaxalone-HPCD produces a smooth induction of anesthesia and rapid recovery with dose-dependent cardiorespiratory depression [9, 26]. On the other hand, induction of anesthesia with escalating IV doses of alfaxalone provides a lower frequency of apnea than with propofol [18]. Alfaxalone-HPCD is also approved for IM administration in cats in Australia. In addition, IM administration of alfaxalone alone or with other sedatives or analgesic drugs has produced sedation or general anesthesia in various veterinary species [4, 11, 12, 19, 33, 39]. However, as far as we know, little information is available on the anesthetic and cardiorespiratory effects of IM alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the dose-dependent sedative and/or anesthetic effects of IM alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs and determine if there are any associated side effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals: Six intact, adult beagle dogs (3 males and 3 females) that were 3 to 5 years of age [4.2 ± 1.0 (mean ± standard deviation) years old] and that weighed 9.0 to 11.5 kg (10.1 ± 0.8 kg) were used in the present study. All dogs were judged to be in good physical condition based upon a physical examination. Food was withheld for at least 12 hr before drug administration, but the dogs were allowed free access to water prior to each treatment. The dogs were cared for according to the principles of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by Rakuno Gakuen University. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Rakuno Gakuen University approved this study (approved No. VH25B7).

Study design: The dogs received 3 IM doses each of 1% alfaxalone-HPCD (Alfaxan, Jurox Pty. Ltd., Rutherford, NSW, Australia) at increasing dose rates of 5 mg/kg (IM5), 7.5 mg/kg (IM7.5) and 10 mg/kg (IM10) every other day over a 5 day period. The IM doses were injected slowly (i.e., approximately 10 ml/min) into the dorsal lumbar muscle of the dog by using a syringe with a 23-gauge, 1-inch needle (TOP injection needle, TOP Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The maximum volume of IM injection was set at 0.5 ml/kg per injection site. Therefore, the IM dose of alfaxalone-HPCD was divided into 2 or 3 syringes and injected into 2 or 3 separate sites on the dorsal lumber muscle when the dogs received the IM7.5 and IM10 treatments. The dogs breathed room air and were endotracheally intubated with an endotracheal tube [Endotracheal tube with cuff (I.D. 7.5 mm), Fuji Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan] when possible after the dog first moved into a position of lateral recumbency. The endotracheal tube was removed when the dog regained its laryngeal reflex. Anesthetic and cardiorespiratory effects of the IM alfaxalone-HPCD were evaluated in the dogs before (baseline) and at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min after starting drug administration.

Evaluation of anesthetic effect: Anesthetic effect was evaluated by the degree of neuro-depression, the quality of anesthetic induction including the ease of tracheal intubation and the quality of recovery from anesthesia. The neuro-depression produced with alfaxalone-HPCD was subjectively evaluated as a sedation score using a composite measurement scoring system modified from a previous report in dogs [41]. The scoring system consisted of 5 categories: spontaneous posture, placement on side, response to noise, jaw relaxation and general attitude. These categories were rated with a score of 0 to 2 for jaw relaxation, 0 to 3 for placement of side and general attitude and 0 to 4 for spontaneous posture and response to noise based on the responsiveness expressed by the dogs (Table 1). Total sedation score was calculated as the sum of the scores for the 5 categories (a maximum of 16). The qualities of anesthetic induction and recovery were assessed using numerical scoring systems modified from one previously used in dogs [30] (Table 2). A well-trained veterinarian (J. T.) was responsible for evaluation of the anesthetic effect of the treatments using these scoring systems mentioned above throughout the present study. In addition, the time of onset of lateral recumbency, placement of the endotracheal tube, the first appearance of spontaneous movement, head lift and unaided standing after starting drug administration, and the durations of acceptance of endotracheal intubation and maintenance of lateral recumbency were observed and recorded.

Table 1. Composite scoring system for evaluating neuro-depressive effects in dogs.

| Spontaneous posture | Score |

| Standing | 0 |

| Tired and standing | 1 |

| Lying but can rise | 2 |

| Lying with difficulty rising | 3 |

| Unable to rise | 4 |

| Placement on side | Score |

| Resists strongly | 0 |

| Modest resistance | 1 |

| Slight resistance | 2 |

| No resistance | 3 |

| Response to noise | Score |

| Jump | 0 |

| Hears and moves | 1 |

| Hears and twitches ear | 2 |

| Barely perceives | 3 |

| No response | 4 |

| Jaw relaxation | Score |

| Poor | 0 |

| Slight | 1 |

| Good | 2 |

| General attitude | Score |

| Excitable | 0 |

| Awake and normal | 1 |

| Tranquil | 2 |

| Stuporous | 3 |

| Total sedation score* | 0–16 |

This scoring system was modified from a previous report in dogs [41] and consisted of 5 categories (spontaneous posture, placement on side, response to noise, jaw relaxation and general attitude). These categories were rated from 0 to 2, 0 to 3 or 0 to 4 based on responsiveness expressed by the dogs. *The total sedation score was calculated as the sum of the scores for the 5 categories: spontaneous posture, placement on side, response to noise, jaw relaxation and general attitude.

Table 2. Scoring systems for evaluating the qualities of anesthetic induction and recovery in dogs.

| Categories | Conditions in dogs |

|---|---|

| Induction score | |

| 4 (Very smooth) | No swallowing, intubation at first attempt, no coughing, no struggling, no vocalization. |

| 3 (Quite smooth) | Some swallowing, intubation after 2–3 attempts, no coughing, some physical movement, no vocalization. |

| 2 (Moderately smooth) | Swallowing a lot, more than 3 attempts to intubate, coughing, vocalization and/or physical movement for more than half the induction time, some distress and excitement. |

| 1 (Poor) | Vocalization and physical movement during entire induction period, major distress aggression or excitement, additional induction agent needed for intubation. |

| Recovery score | |

| 4 (Very smooth) | No excitement. No paddling, vocalizing, trembling or vomiting. No convulsions. |

| 3 (Quite smooth) | A little excitement. Some head movement, possibly some shivering but no paddling, vocalizing, trembling or vomiting. No convulsions. |

| 2 (Moderately smooth) | Moderate excitement. Some paddling, vocalizing, trembling or vomiting. No convulsions. |

| 1 (Poor) | Extreme excitement observed, aggression, vocalizing, violent movements or convulsions. Rescue sedation or anticonvulsant drugs necessary. |

Measurements of cardiorespiratory valuables: Lead II electrocardiography (ECG), heart rate (HR; beats/min) and rectal temperature (RT; °C) were recorded before and after drug administration. Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP; mmHg), percutaneous oxygen saturation of hemoglobin (SpO2; %) and partial pressure of end tidal CO2 (PETCO2; mmHg) were measured when the dogs were intubated. An SpO2 sensor was applied to the tongue and changed periodically. PETCO2 was measured by using a mainstream capnometer. ECG, HR, SpO2 and PETCO2 were recorded by a patient monitoring system (DS-7210, Fukuda Denshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). HR was also counted by thoracic auscultation. Respiratory rate (RR; breaths/min) was counted by observing thoracic movements. RT was measured with a digital thermometer (Thermo flex for animal, Astec Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan). MABP was indirectly measured by an oscillometric method (PetMAP, Ramsey Medical, Inc., Hudson, OH, U.S.A.) using a blood pressure cuff with a width of approximately 40% of the circumference of the measuring site placed around the clipped tail base of each dog. The arterial blood pressure was measured three times at each assessment, and the average of these measurements was defined as the arterial blood pressure.

Statistical analysis: The total sedation, induction and recovery scores were reported as the median ± quartile deviation. The total sedation score was analyzed by the Friedman test to assess changes from baseline values with time for each treatment. Differences in the total sedation, induction and recovery scores among the treatments were compared by Friedman test with the Scheff test for post hoc comparisons. Times related to the anesthetic effects and cardiorespiratory variables were reported as the mean ± standard deviation. The times were compared by paired t test or 1-way (treatment) factorial ANOVA with the Bonferroni test for post hoc comparisons among treatments. The cardiorespiratory variables were analyzed using 2-way (treatment and time) repeated measure ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. Observations and/or perceived adverse effects related to drug administration were compared between treatments by using the chi square test. The level of significant was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

The total injection volumes of alfaxalone were 5.1 ± 0.4 ml for the IM5 treatment, 7.4 ± 0.5 ml for the IM7.5 treatment and 10.2 ± 0.9 ml for the IM10 treatment. Discomfort (vocalizing or struggling) during IM administration was observed in 6 out of 18 occasions [3 dogs (50%) receiving the IM5 treatment, one dog (17%) receiving the IM7.5 treatment and 2 dogs (33%) receiving the IM10 treatment]. There was no significant difference in the incidence of discomfort during IM administration between the treatments (P=0.472). There was no swelling, redness or changes in the skin observed around the site of IM injection during or after the experiment. No dogs showed discomfort during or after the completion of IM injection of alfaxalone-HPCD.

Anesthetic effects: The times associated with the anesthetic effect of each treatment are shown in Table 3. Each treatment produced sedation and lateral recumbency. There was no significant difference in the time of onset of lateral recumbency among the treatments (P=0.103). All dogs could be endotracheally intubated following the IM7.5 and IM10 treatments. On the other hand, endotracheal intubation was not possible in 5 of the 6 dogs receiving the IM5 treatment. The time of head lift and the duration of maintenance of lateral recumbency were considerably longer in the IM7.5 (P=0.007 and P=0.003, respectively) and IM10 (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively) treatments compared with the IM5 treatment. In addition, the times of first appearance of spontaneous movement and unaided standing were markedly longer in the IM10 treatment compared with the IM5 treatment (P=0.010 and P=0.002, respectively).

Table 3. Times related to anesthetic effect after starting intramuscular (IM) administration of alfaxalone in dogs.

| Alfaxalone administration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg/kg IM | 7.5 mg/kg IM | 10 mg/kg IM | |

| Time of onset of lateral recumbency (sec) | 232 ± 90 | 228 ± 88 | 167 ± 25 |

| Time of placement of the endotracheal tube (min) | 9* | 8 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 |

| Time of the first appearance of spontaneous movement (min) | 26 ± 18 | 48 ± 17 | 61 ± 20† |

| Time of head lift (min) | 37 ± 28 | 85 ± 18† | 109 ± 30† |

| Time of unaided standing (min) | 84 ± 31 | 109 ± 38 | 130 ± 28† |

| Duration of acceptance of tracheal intubation (min) | 50* | 46 ± 20 | 58 ± 21 |

| Duration of maintenance of lateral recumbency (min) | 36 ± 28 | 87 ± 26† | 115 ± 29† |

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. †Significant difference from 5 mg/kg IM (P<0.05). *Only one dog accepted tracheal intubation after 5 mg/kg alfaxalone administered IM.

Induction was scored as 4 (very smooth) in one dog (17%), 3 (quite smooth) in 2 dogs (33%) and 2 (moderately smooth) in 3 dogs (50%) receiving the IM10 treatment. In the IM7.5 treatment group, 5 of 6 dogs (83%) received a score of 2, and 1 of 6 dogs (17%) received a score of 1 (poor). In the lowest dose treatment group, IM5, 1 of 6 dogs (17%) received a score of 2, and 5 of 6 dogs (83%) received a score of 1. The median ± quartile deviation induction scores were 1.0 ± 0.0, 2.0 ± 0.0 and 2.5 ± 0.5 for the IM5, IM7.5 and IM10 treatments, respectively. There was a significant difference in the induction score between the IM5 and IM10 treatments (P=0.014).

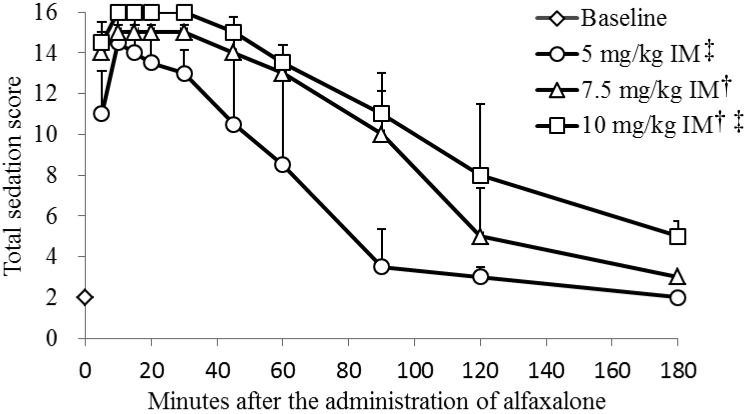

Total sedation scores for each treatment are presented in Fig. 1. A maximum score of 16 was observed in one dog (17%) after the IM5 treatment, 3 dogs (50%) after the IM7.5 treatment and all dogs (100%) after the IM10 treatment. The median total sedation scores peaked at 10 min after the IM5 treatment (median total sedation score 14.5) and at 10 to 30 min after the IM7.5 (median total sedation score 15.0) and IM10 treatments (median total sedation score 16.0). The total sedation score significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.001).

Fig. 1.

Median (± quartile deviation) total sedation scores in 6 dogs before and after starting intramuscular (IM) administration of alfaxalone. Based on the responsiveness expressed by the dogs, jaw relaxation was rated from 0 to 2, placement on the side and general attitude were rated from 0 to 3, and spontaneous posture and response to noise were rated from 0 to 4 using a composite scoring system (see Table 1). The total sedation score was calculated as the sum of the scores for these 5 categories. †Significant difference from 5 mg/kg IM (P<0.05). ‡Significant difference from 7.5 mg/kg IM (P<0.05).

During the recovery period, muscular tremors and a transient staggering gait were observed in all dogs (100%) receiving each treatment. Pronounced limb extension was also observed in 4 dogs (67%), 3 dogs (50%) and 5 dogs (83%) receiving the IM5, IM7.5 and IM10 treatments, respectively. In addition, a transient paddling of the forelimbs was observed in 3 dogs (50%), 2 dogs (33%) and 3 dogs (50%) receiving the IM5, IM7.5 and IM10 treatments, respectively. Recovery was scored as 2 (moderately smooth) in all dogs (100%) receiving each treatment.

Changes in cardiorespiratory valuables: The RT, HR, RR and PETCO2 are summarized in Table 4. The RT gradually decreased from baseline, and a significantly decreased RT was observed from 20 to 180 min after each treatment (P=0.011). There was no significant difference from baseline in the HR after each treatment (P=0.789). The MABPs in the IM7.5 (69 to 125 mmHg) and IM10 treatments (65 to 129 mmHg) were lower than that in the IM5 treatment (111 to 128 mmHg) (P=0.011). Clinically relevant hypotension (MABP <60 mmHg) was not observed during the present study. Spontaneous breathing was maintained, but a dose-dependent decrease in RR was observed (P<0.001). In particular, the IM10 treatment produced clinically relevant hypoxemia (75 to 89% of SpO2) in two dogs (from 10 to 15 min and from 10 to 20 min after each treatment, respectively). In addition, a dog in the IM5 treatment group and two dogs in the IM7.5 treatment group showed transient hypoxemia at 10 or 15 min after each treatment (78 to 88% of SpO2). PETCO2 during intubation after the IM10 treatment was notably higher than that after the IM7.5 treatment (P<0.001).

Table 4. Changes in cardiorespiratory variables before and after starting intramuscular (IM) administration of alfaxalone in dogs.

| Minutes after starting the administration of alfaxalone | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 180 | ||

| RT (°C) | IM5 | 38.1 ± 0.7 | 38.0 ± 0.6 | 37.8 ± 0.6 | 37.6 ± 0.7 | 37.4 ± 0.8* | 37.1 ± 0.7* | 36.7 ± 0.1* | 36.3 ± 1.2* | 36.2 ± 1.5* | 35.5 ± 0.8* | N.D. |

| IM7.5 | 38.3 ± 0.2 | 38.0 ± 0.3 | 37.6 ± 0.3 | 37.5 ± 0.3 | 37.3 ± 0.4* | 37.1 ± 0.3* | 36.5 ± 0.3* | 36.1 ± 0.3* | 36.0 ± 0.6* | 36.2 ± 0.9* | N.D. | |

| IM10 | 37.9 ± 0.5 | 37.7 ± 0.3 | 37.4 ± 0.5 | 37.3 ± 0.4 | 37.2 ± 0.5* | 37.0 ± 0.4* | 36.6 ± 0.4* | 36.3 ± 0.6* | 35.9 ± 0.6* | 36.0 ± 0.6* | 35.7 ± 0.6* | |

| HR (beats/min) | IM5 | 115 ± 17 | 112 ± 14 | 126 ± 19 | 121 ± 18 | 116 ± 19 | 111 ± 31 | 118 ± 37 | 110 ± 31 | 110 ± 35 | 119 ± 21 | N.D. |

| IM7.5 | 120 ± 16 | 117 ± 15 | 132 ± 22 | 130 ± 24 | 121 ± 24 | 109 ± 22 | 98 ± 22 | 91 ± 22 | 90 ± 33 | 96 ± 22 | N.D. | |

| IM10 | 111 ± 19 | 121 ± 13 | 138 ± 17 | 137 ± 15 | 131 ± 14 | 117 ± 12 | 101 ± 9 | 97 ± 17 | 95 ± 34 | 85 ± 27 | 128 ± 39 | |

| RR (breaths/min) | IM5‡ | 34 ± 7 | 21 ± 7* | 20 ± 9* | 19 ± 8* | 20 ± 11* | 19 ± 15* | 23 ± 10* | 24 ± 12* | 16 ± 6* | 20 ± 0* | N.D. |

| IM7.5† | 31 ± 9 | 24 ± 9* | 13 ± 5* | 11 ± 5* | 11 ± 4* | 12 ± 5* | 14 ± 6* | 13 ± 7* | 15 ± 6* | 24 ± 16* | N.D. | |

| IM10†‡ | 23 ± 6 | 12 ± 4* | 8 ± 4* | 6 ± 3* | 6 ± 2* | 7 ± 2* | 9 ± 3* | 14 ± 6* | 13 ± 3* | 16 ± 5* | 20 ± 4 | |

| PETCO2 (mmHg) | IM5 | N.D. | N.D. | 46 | 49 | 45 | 45 | 44 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| IM7.5 | N.D. | N.D. | 46 ± 3 | 46 ± 2 | 45 ± 2 | 44 ± 2 | 43 ± 2 | 41 ± 1 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| IM10†‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 48 ± 1 | 51 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 | 50 ± 2 | 47 ± 1 | 45 ± 1 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

Data are expessed as the mean ± standard deviation. RT: Rectal tempareture, HR: Heart rate, RR: Respiratory rate, PETCO2, Partial pressure of end tidal CO2, IM5: IM administration of 5 mg/kg alfaxalone, IM7.5: IM administration of 7.5 mg/kg alfaxalone, IM10: IM administration of 10 mg/kg alfaxalone, N.D.: Not done. PETCO2 was measured during intubation. Observation was completed at 120 min after the IM5 and IM7.5 treatments, because the dogs recovered from the sedation or general anesthesia and could get up and walk normally. * Significant difference from baseline value (P<0.05). †Significant difference from 5 mg/kg IM (P<0.05). ‡Significant difference from 7.5 mg/kg IM (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD produced a dose-dependent anesthetic effect with mild dose-dependent cardiorespiratory depression in healthy dogs. The IM doses of alfaxalone-HPCD at 7.5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg produced loss of sensation of external stimuli (i.e., anesthesia) and enabled endotracheal intubation. During the recovery period from anesthesia, muscular tremors and a transient staggering gait were commonly observed in the dogs. It can be concluded that IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD at 7.5 and 10 mg/kg provided reliable and repeatable induction of anesthesia in dogs. On the other hand, IM alfaxalone-HPCD at 5 mg/kg produced only sedation and immobilization.

Muir et al. [26] reported that IV administration of alfaxalone at 2 and 6 mg/kg produced good to excellent short-term anesthesia in dogs. In our pilot study leading up to this present study, it was verified that an IM injection of alfaxalone-HPCD at 2.5 mg/kg (0.25 ml/kg) did not produce anesthesia but did produce some degree of sedation. This IM dose of alfaxalone is similar to an IV anesthetic induction dose of alfaxalone in dogs. Based on the dosing recommendations from the product information sheet, 10 mg/kg alfaxalone (double the IV anesthetic induction dose of alfaxalone) administered IM is expected to induce deep sedation or light anesthesia in cats. The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries Associations and the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods provides a guideline for the administration of IM volumes [7]. The reported IM volume considered as good practice is 0.25 ml/kg, and the maximal dose volume is 0.5 ml/kg in dogs [7]. The concentration of alfaxalone in the approved product is 10 mg/ml. Thus, we chose three increasing IM doses of alfaxalone-HPCD, 5 mg/kg (0.5 ml/kg), 7.5 mg/kg (0.75 ml/kg) and 10 mg/kg (1 ml/kg), in the present study and a maximum dose volume of 0.5 ml/kg per injection site. In 6 out of 18 occasions, the dogs showed discomfort during IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD, but there was no significant difference in the frequency of discomfort between treatments. Alfaxalone-HPCD has a neutral pH and does not cause pain and tissue irritation after IV administration [24] or perivascular injection (Heit et al. 2004. Safety and efficacy of Alfaxan®-CD RTU administrated once to cats subcutaneously at 10 mg/kg. Proceedings of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Minneapolis, Minnesota, p.432). We propose that the discomfort observed in the study was a volume effect and not a property of the alfaxalone-HPCD formulation itself. Therefore, the development of a more concentrated alfaxalone-HPCD product for IM administration is desirable in order to reduce the discomfort observed from having to administer such large volumes of the product to produce sedation and/or anesthesia in dogs.

In the present study, we intended to find out, if we could produce anesthesia in dogs after IM alfaxalone-HPCD administration. However, it was anticipated that nociceptive stimulation would have some influence on the evaluation of the neuro-depressive effects produced by alfaxalone-HPCD because of its poor analgesic properties [27]. Therefore, we adopted the scoring system that we thought would include the least amount of nociceptive stimulation during repeated assessment of neuro-depressive effects and cardiorespiratory variables. The composite measure scoring system used for determining the neuro-depressive effects of alfaxalone-HPCD in the present study was modified from an existing scoring system used for evaluating sedative and analgesic effects of medetomidine in dogs [41]. This scoring system consisted of 6 categories (spontaneous posture, placement on side, response to noise, jaw relaxation, general attitude and nociceptive response to interdigital pad pinch) [41]. Therefore, we modified our scoring system from this existing scoring system [41] by removing the category of nociceptive response to interdigital pad pinch, because it was not relevant.

IV administration of alfaxalone-HPCD produces a rapid induction of anesthesia in dogs [9, 22, 26]. Ferré et al. [9] reported that all 8 dogs in their study receiving an IV bolus of alfaxalone-HPCD at 2 and 10 mg/kg accepted tracheal intubation for 6.4 ± 2.9 min and 26.2 ± 7.5 min, respectively. Muir et al. [26] reported that IV doses of alfaxalone-HPCD produced a dose-dependent anesthetic effect in dogs with the times from induction to tracheal extubation reported as 9.8 ± 2.4, 31.4 ± 6.9 and 75.1 ± 18.9 min at the IV doses of 2, 6 and 20 mg/kg, respectively. Maney et al. [22] reported that the IV induction dose of alfaxalone-HPCD was 2.6 ± 0.4 mg/kg in 8 dogs and that the dogs accepted tracheal intubation for 11 ± 7 min. In the present study, the IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD also produced a clinically relevant neuro-depressive effect in a dose-dependent manner, and tracheal intubation was possible in all dogs receiving the IM7.5 and IM10 treatments. The IM7.5 and IM10 treatments produced a slower induction of anesthesia, but provided longer durations of acceptance of tracheal intubation compared with those produced by IV alfaxalone-HPCD [9, 22, 26]. However, the IM5 treatment produced about 30 to 45 min of sedation, but failed to produce anesthesia in dogs. It is concluded that the proper IM anesthetic induction dose of alfaxalone-HPCD is greater than 5 mg/kg body weight in unpremedicated healthy dogs. An IM dose of alfaxalone-HPCD at 5 mg/kg is insufficient for tracheal intubation, but may provide enough sedation and immobilization to complete less invasive procedures, such as securing vascular access, in unpremedicated healthy dogs.

It has been reported that IV administration of alfaxalone-HPCD resulted in uneventful recovery in dogs [2, 26] and cats [27, 37]. On the other hand, it has also been reported that IV alfaxalone-HPCD produced more undesirable events during the recovery period in dogs [16, 22] and cats [23, 42] compared with IV propofol. In the present study, almost all dogs exhibited muscular tremors, pronounced limb extension, paddling and vocalizing during the early period of recovery, but no dog was excited or behaved aggressively. Maney et al. [22] reported that tremors (50%), vocalizing (25%) and paddling (12.5%) were observed during recovery from IV alfaxalone-HPCD anesthesia in 8 dogs in their study and that induction of anesthesia with IV alfaxalone-HPCD was associated with more episodes of these undesirable events compared with induction of anesthesia with propofol. It was also reported that a similar extent of ataxia was observed after both IV alfaxalone anesthesia and propofol anesthesia [22]. These events are similar to those observed in our study, but the frequency of muscular tremors and paddling during recovery were higher than those observed in the previous report [22]. This difference in frequency of these observable effects is most likely associated with the differences in the pharmacokinetics of alfaxalone after IV versus IM administration. Unfortunately, the pharmacokinetics of alfaxalone after alfaxalone-HPCD IM administration were not investigated in this study.

Quirós et al. [31] showed that the quality of recovery from total intravenous anesthesia with alfaxalone-HPCD combined with a continuous rate infusion of dexmedetomidine was better than that from total intravenous anesthesia with alfaxalone-HPCD alone. In addition, it has been reported that total intravenous anesthesia with alfaxalone-HPCD following premedication with buprenorphine and acepromazine produced a better quality of recovery from anesthesia than that following premedication with buprenorphine and dexmedetomidine in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy [14]. Herbert et al. [14] mentioned that the shorter duration of dexmedetomidine sedation might have increased the probability of dogs exhibiting signs of undesirable events during recovery from alfaxalone-HPCD anesthesia. These findings indicate that premedication with other sedative and analgesic drugs may improve the quality of recovery from alfaxalone-HPCD anesthesia in dogs. Further studies will be necessary to determine the influence of premedication on the quality of recovery from IM alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs and dose-sparing effects on alfaxalone-HPCD.

Muir et al. [26] reported that an IV administration of alfaxalone-HPCD resulted in dose-dependent changes in cardiovascular and respiratory parameters in dogs. Intravenous administration of alfaxalone at 6 mg/kg produced hypoxia associated with hypoventilation mainly caused by a decrease in respiratory rate and transient apnea, although the cardiovascular status was well maintained [26]. In addition, Maney et al. [22] showed that the cardiopulmonary status was well maintained after an induction dose of alfaxalone (2.6 ± 0.4 mg/kg IV) in dogs. In these previous studies, the dogs were not administered supplemental oxygen [22, 26]. In the present study, the MABP at the higher doses (both the IM7.5 and IM10 treatments) was lower than that for the IM5 treatment, but the changes in MABP were within a clinically acceptable normal range in all the dogs receiving the IM5, IM7.5 and IM10 treatments. Spontaneous breathing was maintained in all dogs, but a dose-dependent decrease in RR and increase in PETCO2 were observed. In addition, clinically relevant hypoxemia for 5 to 10 min was observed in two dogs after the IM10 treatment, and transient hypoxemia was detected in one dog in the IM5 treatment group and two dogs in the IM7.5 treatment group. These findings suggest that IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD produces dose-dependent cardiorespiratory depression in dogs starting at 5 mg/kg similar to that observed after IV alfaxalone-HPCD. In particular, attention should be paid to the hypoxemia associated with the decrease in RR, although the cardiovascular parameters were well maintained after IM administration of alfaxalone-HPCD. As is the case when using any general anesthetics, supplemental oxygen should be administered to prevent hypoxemia. In the present study, we used the oscillometric method to measure blood pressure in order to achieve less nociceptive stimulation in each dog. The oscillometric method may result in a minor underestimation of the arterial blood pressure compared with direct arterial blood pressure measurement in dogs [34], although the accuracy of the blood pressure measurement device used in the present study compared with measurement of the direct arterial blood pressure has not been well documented. In the present study, we used the arterial blood pressure values during the period of acceptance of tracheal intubation, because animal motion may affect the accuracy of the arterial blood pressure measured by the oscillometric method. In addition, inadequate light transmission and animal movement are the greatest limitations of SpO2 measurement [15]. Thus, SpO2 was also evaluated during the period of acceptance of tracheal intubation. We changed the SpO2 sensor site periodically to avoid the influence on tissue perfusion caused by the sensor clip. Further sophisticated cardiorespiratory measurement including arterial blood gas analysis and measurement of cardiac output or tidal volume will be required to confirm the cardiopulmonary effect of IM alfaxalone-HPCD in dogs.

The limitation of the present study is that plasma biochemistry was not performed before each treatment. In the present study, clinical signs of liver failure including ascites, jaundice, hypoactivity and anorexia were not observed. The main elimination pathway of alfaxalone is considered biotransformation by cytochrome P450s and conjugation enzymes in the liver. There is some evidence suggesting the influence of liver metabolism on the effects of a previous alfaxalone product (Althesin®) [29, 35]. Hepatic enzyme activity was depressed for the duration of the effects of Althesin®, although it did not increase the intensity compared with the normal situation in rats [29]. The length of action is not prolonged in patients with anuria [36]. In the present study, repetitive alfaxalone administration every other day might have affected the anesthetic effects of alfaxalone. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of alfaxalone including its rapid onset and short duration of action with high total body clearance resulted in little accumulation following repeated bolus IV administration [9, 26], so it can be used for total intravenous anesthesia in dogs [14, 31]. The higher dose of alfaxalone was expected to produce a longer duration of anesthesia and a higher intensity in a dose-dependent manner [26]. However, there was no difference in the duration of anesthesia between the IM7.5 and IM10 treatments, although a significant difference in neuro-depressive effect was detected in the present study. This result suggests that the negative influence of liver condition on the metabolism of alfaxalone and the cumulative effects associated with repetitive administration played less of a part in the effects of alfaxalone in the present study. We also surmised that some enzyme induction in the liver associated with repetitive alfaxalone administration might affect metabolism of the drug in the IM10 treatment. Further investigations on the pharmacokinetic properties after IM alfaxalone administration will be required.

In conclusion, IM alfaxalone-HPCD at 7.5 and 10 mg/kg produced an adequate loss of sensation (i.e., anesthesia) to permit endotracheal intubation in dogs. The duration of acceptance of endotracheal intubation after IM alfaxalone-HPCD at 7.5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg was longer compared with that in the past reports after IV alfaxalone at similar doses. At these same dose rates, only mild cardiovascular depression was observed, although hypoxemia associated with a decrease in RR did occur. IM alfaxalone-HPCD at 5 mg/kg was insufficient to produce anesthesia, although a short duration of sedation and immobilization with mild cardiorespiratory depression was observed in dogs. Other observations included discomfort associated with large injection volumes in addition to muscle tremors, pronounced limb extension, paddling and vocalization during recovery, undesirable effects that would likely be diminished if the alfaxalone-HPCD was a more concentrated product administered concurrently with other centrally acting agents (e.g., opioids, benzodiazepines, α2 adrenergic receptor agonists).

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson T. E., Walby W. F., Joy R. M.1992. Modification of GABA-mediated inhibition by various injectable anesthetics. Anesthesiology 77: 488–499. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199209000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambros B., Duke-Novakovski T., Pasloske K. S.2008. Comparison of the anesthetic efficacy and cardiopulmonary effects of continuous rate infusions of alfaxalone-2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin and propofol in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 69: 1391–1398. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.69.11.1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branson K. R.2007. Injectable and alternative anesthetic techniques. pp. 273–300. In: Lumb and Jones’ Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 4th ed. (Tranquilli, W. J., Thurmon, J. C. and Grimm, K. A. eds.), Blackwell Publishing, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertelsen M. F., Sauer C. D.2011. Alfaxalone anaesthesia in the green iguana (Iguana iguana). Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 38: 461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Child K. J., Currie J. P., Davis B., Dodds M. G., Pearce D. R., Twissell D. J.1971. The pharmacological properties in animals of CT1341–a new steroid anaesthetic agent. Br. J. Anaesth. 43: 2–13. doi: 10.1093/bja/43.1.2-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen L. K.1996. Medetomidine sedation in dogs and cats: a review of its pharmacology, antagonism and dose. Br. Vet. J. 152: 519–535. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1935(96)80005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diehl K. H., Hull R., Morton D., Pfister R., Rabemampianina Y., Smith D., Vidal J. M., van de Vorstenbosch C.2001. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 21: 15–23. doi: 10.1002/jat.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodman N. H.1980. Complications of saffan anaesthesia in cats. Vet. Rec. 107: 481–483. doi: 10.1136/vr.107.21.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferré P. J., Pasloske K., Whittem T., Ranasinghe M. G., Li Q., Lefebvre H. P.2006. Plasma pharmacokinetics of alfaxalone in dogs after an intravenous bolus of Alfaxan-CD RTU. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 33: 229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2005.00264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodchild C. S., Guo Z., Nadeson R.2000. Antinociceptive properties of neurosteroids I. Spinally-mediated antinociceptive effects of water-soluble aminosteroids. Pain 88: 23–29. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00301-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grubb T. L., Greene S. A., Perez T. E.2013. Cardiovascular and respiratory effects, and quality of anesthesia produced by alfaxalone administered intramuscularly to cats sedated with dexmedetomidine and hydromorphone. J. Feline Med. Surg. 15: 858–865. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13478265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen L. L., Bertelsen M. F.2013. Assessment of the effects of intramuscular administration of alfaxalone with and without medetomidine in Horsfield’s tortoises (Agrionemys horsfieldii). Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: e68–e75. doi: 10.1111/vaa.12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartsfield S. M.2007. Anesthetic machines and breathing systems. pp. 453–494. In: Lumb and Jones’ Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 4th ed. (Tranquilli, W. J., Thurmon, J. C. and Grimm, K. A. eds.), Blackwell Publishing, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbert G. L., Bowlt K. L., Ford-Fennah V., Covey-Crump G. L., Murrell J. C.2013. Alfaxalone for total intravenous anaesthesia in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy: a comparison of premedication with acepromazine or dexmedetomidine. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: 124–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2012.00752.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson J. D., Miller M. W., Matthews N. S., Hartsfield S. M., Knauer K. W.1992. Evaluation of accuracy of pulse oximetry in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53: 537–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiménez C. P., Mathis A., Mora S. S., Brodbelt D., Alibhai H.2012. Evaluation of the quality of the recovery after administration of propofol or alfaxalone for induction of anaesthesia in dogs anaesthetized for magnetic resonance imaging. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 39: 151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karas A. Z.1999. Sedation and chemical restraint in the dog and cat. Clin. Tech. Small Anim. Pract. 14: 15–26. doi: 10.1016/S1096-2867(99)80023-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keates H., Whittem T.2012. Effect of intravenous dose escalation with alfaxalone and propofol on occurrence of apnoea in the dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 93: 904–906. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kischinovsky M., Duse A., Wang T., Bertelsen M. F.2013. Intramuscular administration of alfaxalone in red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans)–effects of dose and body temperature. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: 13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2012.00745.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko J. C., Fox S. M., Mandsager R. E.2000. Sedative and cardiorespiratory effects of medetomidine, medetomidine-butorphanol, and medetomidine-ketamine in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 216: 1578–1583. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.216.1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert J. J., Belelli D., Peden D. R., Vardy A. W., Peters J. A.2003. Neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 71: 67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maney J. K., Shepard M. K., Braun C., Cremer J., Hofmeister E. H.2013. A comparison of cardiopulmonary and anesthetic effects of an induction dose of alfaxalone or propofol in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: 237–244. doi: 10.1111/vaa.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathis A., Pinelas R., Brodbelt D. C., Alibhai H.2012. Comparison of quality of recovery from anaesthesia in cats induced with propofol or alfaxalone. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 39: 282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michou J. N., Leece E. A., Brearley J. C.2012. Comparison of pain on injection during induction of anaesthesia with alfaxalone and two formulations of propofol in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 39: 275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2012.00709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muir W. W., Ford J. L., Karpa G. E., Harrison E. E., Gadawski J. E.1999. Effects of intramuscular administration of low doses of medetomidine and medetomidine-butorphanol in middle-aged and old dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 215: 1116–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muir W., Lerche P., Wiese A., Nelson L., Pasloske K., Whittem T.2008. Cardiorespiratory and anesthetic effects of clinical and supraclinical doses of alfaxalone in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 35: 451–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2008.00406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muir W., Lerche P., Wiese A., Nelson L., Pasloske K., Whittem T.2009. The cardiorespiratory and anesthetic effects of clinical and supraclinical doses of alfaxalone in cats. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 36: 42–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2008.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutoh T., Kanamaru A., Suzuki H., Tsubone H., Nishimura R., Sasaki N.2001. Respiratory reflexes in spontaneously breathing anesthetized dogs in response to nasal administration of sevoflurane, isoflurane, or halothane. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62: 311–319. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novelli G. P., Marsili M., Lorenzi P.1975. Influence of liver metabolism on the actions of althesin and thiopentone. Br. J. Anaesth. 47: 913–916. doi: 10.1093/bja/47.9.913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Psatha E., Alibhai H. I., Jimenez-Lozano A., Armitage-Chan E., Brodbelt D. C.2011. Clinical efficacy and cardiorespiratory effects of alfaxalone, or diazepam/fentanyl for induction of anaesthesia in dogs that are a poor anaesthetic risk. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 38: 24–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2010.00577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quirós Carmona S., Navarrete-Calvo R., Granados M. M., Dominguez J. M., Morgaz J., Fernández-Sarmiento J. A., Muňoz-Rascón P., Gómez-Villamandos R. J.2014. Cardiorespiratory and anaesthetic effects of two continuous rate infusions of dexmedetomidine in alfaxalone anaesthetized dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 97: 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson K. J., Jones R. S., Cripps P. J.2001. Effects of medetomidine and buprenorphine administered for sedation in dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 42: 444–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2001.tb02498.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos González M., Bertran de Lis B. T., Tendillo Cortijo F. J.2013. Effects of intramuscular alfaxalone alone or in combination with diazepam in swine. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 40: 399–402. doi: 10.1111/vaa.12033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawyer D. C., Guikema A. H., Siegel E. M.2004. Evaluation of a new oscillometric blood pressure monitor in isoflurane-anesthetized dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 31: 27–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2004.00141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sear J. W., McGivan J. D.1981. Metabolism of alphaxalone in the rat: evidence for the limitation of the anaesthetic effect by the rate of degradation through the hepatic mixed function oxygenase system. Br. J. Anaesth. 53: 417–424. doi: 10.1093/bja/53.4.417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strunin L., Strunin J. M., Knights K. M., Ward M. E.1977. Metabolism of 14C- labelled alphaxalone in man. Br. J. Anaesth. 49: 609–614. doi: 10.1093/bja/49.6.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taboada F. M., Murison P. J.2010. Induction of anaesthesia with alfaxalone or propofol before isoflurane maintenance in cats. Vet. Rec. 167: 85–89. doi: 10.1136/vr.b4872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomizawa N., Tomita I., Nakamura K., Hara S.1997. A comparative study of medetomidine-butotphanol-ketamine and medetomidine-ketamine anaesthesia in dogs. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. A 44: 189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1997.tb01100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas A. A., Leach M. C., Flecknell P. A.2012. An alternative method of endotracheal intubation of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Lab. Anim. 46: 71–76. doi: 10.1258/la.2011.011092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueyama Y., Waselau A. C., Wiese A. J., Muir W. W.2008. Anesthetic and cardiopulmonary effects of intramuscular morphine, medetomidine, ketamine injection in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 35: 480–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2008.00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young L. E., Brearley J. C., Richards D. L. S., Bartram D. H., Jones R. S.1990. Medetomidine as a premedicant in dogs and its reversal by atipamezole. J. Small Anim. Pract. 31: 554–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1990.tb00685.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaki S., Ticehurst K., Miyaki Y.2009. Clinical evaluation of Alfaxan-CD® as an intravenous anaesthetic in young cats. Aust. Vet. J. 87: 82–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2009.00390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]