Abstract

Adult stem cell treatment is a potential novel therapeutic approach for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Given the extremely low rate of cell engraftment, it is believed that these cells exert their beneficial effects via paracrine mechanisms. However, the endogenous mediator(s) in the pulmonary vasculature remains unclear. Employing the mouse model with endothelial cell (EC)-restricted disruption of FoxM1 (FoxM1 CKO), here we show that endothelial expression of the reparative transcriptional factor FoxM1 is required for the protective effects of bone marrow progenitor cells (BMPC) against LPS-induced inflammatory lung injury and mortality. BMPC treatment resulted in rapid induction of FoxM1 expression in WT but not FoxM1 CKO lungs. BMPC-induced inhibition of lung vascular injury, resolution of lung inflammation, and survival, as seen in WT mice, were abrogated in FoxM1 CKO mice following LPS challenge. Mechanistically, BMPC treatment failed to induce lung EC proliferation in FoxM1 CKO mice, which was associated with impaired expression of FoxM1 target genes essential for cell cycle progression. We also observed that BMPC treatment enhanced endothelial barrier function in WT, but not in FoxM1-deficient EC monolayers. Restoration of β-catenin expression in FoxM1-deficient ECs normalized endothelial barrier enhancement in response to BMPC treatment. These data demonstrate the requisite role of endothelial FoxM1 in the mechanism of BMPC-induced vascular repair to restore vascular integrity and accelerate resolution of inflammation, thereby promoting survival following inflammatory lung injury.

Keywords: adult stem cells, acute respiratory distress syndrome, FoxM1, inflammation, vascular integrity

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), is a multi-factorial syndrome characterized by lung inflammation and intractable hypoxemia, leading to increased lung microvascular permeability, transudation of plasma proteins, and formation of persistent protein-rich lung edema [1–3]. These patients are often septic and prognosis is typically poor with a mortality rate of 25–40% [2, 3]. Despite the recent advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ARDS, there is no cure for this disease. Current treatment remains primarily supportive [3, 4].

The endothelial cell (EC) monolayer lining the intima of blood vessels forms a selective, semi-permeable barrier that regulates the vital tasks of tissue fluid homeostasis and migration of blood cells across the vessel wall [5]. A fundamental pathological change found in ARDS that results from sepsis is injury to the endothelial barrier, and, as a result, increased vascular permeability to protein [6, 7]. Thus, restoration of microvessel barrier function following the injury is essential for maintaining tissue fluid balance and reversing lung edema. It has been reported that circulating endothelial progenitor cells are increased in patients with acute community-acquired pneumonia and that an increased number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells is associated with increased survival after ARDS [8, 9], indicating bone marrow-derived progenitor cells play an important role in inhibiting lung injury and promoting survival in patients. We have shown that cultured mouse bone marrow progenitor cells (BMPC) enhance endothelial adherens junction integrity and thereby inhibit lung vascular injury following LPS [10, 11] and thrombin [12] challenge. The protective effect is likely mediated by BMPC-released sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) [10]. These studies as well as other studies with mesenchymal stem cells [13–22] provide clear evidence that adult stem/progenitor cell-based therapy is a promising novel approach to treatment of ARDS. Given that the engraftment rates of these cells are extremely low and the therapeutic benefits are rapidly seen within hours post-transplantation, it is well received that these cells exert their beneficial effects via paracrine mechanisms. However, the endogenous mediator(s) in the pulmonary vasculature remains unclear.

Employing the mouse model with EC-restricted disruption of FoxM1 (FoxM1 CKO) as well as FoxM1 transgenic mice, our recent studies have demonstrated a critical role of the forkhead transcriptional factor FoxM1 in regulating endothelial proliferation as well as re-annealing of the endothelial adherens junctions and thereby endothelial barrier repair following lung vascular injury [23–25]. FoxM1 mediates G1/S and G2/M transition secondary to transcriptional control of target genes involved in cell cycle progression [23, 26–28] and also re-annealing of endothelial cell-cell contacts through transcriptional control of β-catenin [24]. Although FoxM1 expression is silenced in pulmonary vascular EC in adult lungs, it is markedly induced in lung EC but only during the repair phase following sepsis-induced vascular injury [23, 25]. Thus, the goal of this study is to determine the role of exogenous BMPC in regulating FoxM1 expression in the pulmonary vasculature and to test the hypothesis that endothelial FoxM1 is an intrinsic mediator of exogenous adult stem/progenitor cell-induced protection from lung injury and vascular repair, which leads to restoration of lung vascular integrity and resolution of lung inflammation following sepsis challenge.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Generation of mice with EC-specific inactivation of FoxM1 (FoxM1 CKO) has been described previously [23, 24]. Littermates with FoxM1 floxed allele but no Cre (FoxM1 fl/fl) were used as WT whereas FoxM1 fl/fl and Cre were used as FoxM1 CKO (all in C57B/6 background). Both male and females at age of 3±0.5 months were used for experiments. All mice were bred and maintained in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited animal facilities at the University of Illinois at Chicago according to NIH guidelines. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of mouse BMPCs

Mouse BMPC were isolated and expanded in culture as described previously [10–12]. Briefly, the femora and tibias were stripped from muscle and connective tissue and the bones were cut at both ends. Bone marrow was flushed out with HBSS using a 25 gauge needle. To obtain the maximal amount of bone marrow cells, the femora and tibias were cut into small pieces, including the epiphyseal line and the endosteum, and were incubated with 10 mL of collagenase A solution (1.0 mg/mL in HBSS) in a 37°C-waterbath with gentle shaking. The digested mixtures of small bone pieces together with the initial bone marrow HBSS flush were then filtered using a 40μm nylon filter. Mononuclear cells were isolated by a density gradient (Ficoll-Paque, GE Healthcare) following centrifugation at 1600rpm for 30 min. The cells were re-suspended in EBM-2MV endothelial culture media using the supplement kit (Lonza) and cultured in gelatin-coated tissue culture flasks at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Following medium change at 48 h post-culture to remove the non-adherent cell population, the attached cells were then cultured for another 16–18 days with medium change every 3 days and passaged once (1:2 split). When the cells were grown to approximately 75% confluence, the cells were directly collected for experiments without FACS sorting since approximately 80% of these cells express the progenitor cell markers Sca1, CD133 and CD34 but not CD45 and CD31.

Cell transplantation in mice

At 2h post-LPS challenge (i.p.), mice were injected with 0.2 × 106 BMPC (in 200 μl PBS) or PBS (control) through tail vein injection. Except

Vascular permeability assessment

The Evans blue-conjugated albumin (EBA) extravasation assay was performed as previously described [25, 29]. EBA at a dose of 20 mg/kg BW was retroorbitally injected to mice 30 minutes before tissue collection. Lungs were perfused free of blood with PBS, blotted dry, and weighed. Lung tissue was homogenized in 1 ml PBS and incubated with 2 volumes of formamide at 60°C for 18 hours. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 minutes. The optical density of the supernatant was determined at 620 nm and 740 nm. The extravasated EBA in lung homogenate was expressed as μg of Evans blue dye per g lung tissue.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay

MPO activity was measured as previously described [23, 30]. Briefly, lung tissues were collected following perfusion free of blood with PBS and homogenized in 50 mM phosphate buffer. Homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Thereafter the pellets were resuspended in phosphate buffer containing 0.5% hexadecyl trimethylammonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) and subjected to a cycle of freezing and thawing. Subsequently the pellet was homogenized and the homogenates were centrifuged again. The supernatants were assayed for MPO activity using kinetics readings for 3 min and absorbance was measured at 460 nm. The results were presented as ΔOD460/min/g lung tissue.

Histological analysis

Following PBS perfusion, mouse lung tissues were fixed for 5 min by instillation of 10% PBS-buffered formalin through tracheal catheterization at a trans-pulmonary pressure of 150 mm H2O. After tracheal ligation, harvested lungs were fixed with 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C with agitation. After paraffin processing, the tissues were sectioned at 4 to 5 μm thick for H & E staining.

Molecular analysis

Total RNA was isolated from mouse lung tissue using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) including DNase I digestion to avoid DNA contamination. SYBR Green-based quantitative real time RT-PCR analyses were performed in ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies). Primers for mouse and human FoxM1 were published previously [23]. Primers for human β-catenin and mouse Cyclin A2, Cyclin B1, Cdc25C, TNF-α, and MCP-1 were purchased from Qiagen. Expression of mouse genes was normalized to mouse cyclophilin as an internal control while expression of human genes was normalized to human 18s rRNA [24].

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed using anti-Cdc25C (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc), anti-FoxM1 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc), and anti-β-actin (1:3000, BD Biosciences).

In situ cell proliferation analysis

BrdU labeling and immunostaining were used to evaluate cell proliferation in mouse lung sections [23, 25]. BrdU (75mg/kg BW) was administered i.p. to mice at 4h prior to tissue collection. Mouse lung cryosections (5 μm) were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU using the In Situ Cell Proliferation kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science). Endothelial cells were stained with anti-CD31 (1:40, Abcam) and -vWF (1:250, Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies while nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen).

FoxM1 siRNA-mediated gene knockdown and β-catenin expression

Human lung microvascular EC (Lonza) were cultured in T75 flasks precoated with 0.2% gelatin in EBM-2 complete medium supplemented with 15% FBS and EGM-2 MV Singlequots (Lonza), and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cells were used for experiments between four and seven passages. When grown to 80–90% confluency, the cells were collected for transfection with FoxM1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) or scrambled RNA oligonucleotides (scRNA) [23, 24] using the HLMVEC Nucleofector kit (Lonza). To express β-catenin in FoxM1-deficient EC, plasmid DNA expressing human β-catenin under the control of CMV promoter were cotransfected with FoxM1 siRNA whereas empty vector DNA was used as control as described previously [24]. At 65h post-transfection, the cells were used for experiments.

3H-Thymidine incorporation assay

Incorporation of 3H-Thymidine in human lung microvascular EC as an index of DNA synthesis was measured as described previously [31]. After 4h incubation in starvation medium (1:75 dilution of the complete EBM2 medium with serum-free basal medium), BMPC (0.2 × 106 cells/well) or control lung microvascular EC maintained in the upper chamber of the transwell plate were placed on top of the human lung microvascular EC which were grown in the lower chamber of the transwell plate. The EC transfected with FoxM1 siRNA or scRNA were used at 40–50% confluence following 24h incubation in starvation medium. After 12 h co-culture, 3H-thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol; MP Biomedicals) was then added to the medium at a concentration of 1 μCi/ml, and the cells were cultured for another 7 h. Cells were then washed with PBS twice and 10% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) once, and 10% trichloroacetic acid was added to precipitate protein at 4°C for 45 min. The precipitate was washed twice with 95% ethanol, resuspended in 0.15 N NaOH, and saturated with 1 M HCl. Aliquots were counted in a scintillation counter. The results are expressed as cpm/dish.

Transendothelial monolayer electrical resistance (TER)

Real-time endothelial junctional changes were determined using an electric cell substrate impedance sensor to measure real-time changes in electrical resistance across endothelial monolayers as described [10, 12, 24]. In brief, after transfection, human lung microvascular EC was plated at confluence on a ECIS chamber with small gold electrode (Applied Biophysics). The small electrode and the larger counter electrode were connected to a phase-sensitive lock-in amplifier. An approximate constant current of 1 μA was supplied by a 1-V, 4,000-Hz alternating current signal connected serially to a 1–MΩ resistor between the small electrode and the larger counter electrode. The voltage between the small electrode and the large electrode was monitored by a lock-in amplifier, stored, and processed with a computer. The same computer controlled the output of the amplifier and switched the measurement to different electrodes in the course of an experiment. Before the experiment, the confluent endothelial monolayer was kept in 0.5% FBS-containing medium for 2 h. After 30 min of recording the TER at baseline, the endothelial monolayers were treated with either 5000 BMPC/well (in 50 μl PBS) or 50μl PBS. BMPC-induced change in resistance was monitored up to 3 h and normalized to baseline value.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using Student’s t-test or ANOVA with Bonferroni correction wherever appropriate. Statistical analysis in the mortality study following LPS challenge was performed with the Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. There are no samples/animals excluded based on the pre-established inclusion/exclusion criteria, which is that the difference from the mean is more than 2-times of the SD.

Results

BMPC induces FoxM1 expression in pulmonary vasculature

To determine whether BMPC treatment induces FoxM1 expression in the pulmonary vasculature, 200,000 BMPC [expressing the progenitor cell markers including Sca1, CD133, and CD34 but not the leukocyte marker CD45 (Supplemental Figure S1)] [10–12] were transplanted to either WT or FoxM1 CKO mice at 2h post-LPS challenge. The same amount of PBS was administered to separate groups of WT or FoxM1 CKO mice as controls. As shown in Figure 1A, FoxM1 was not induced until 48h post-LPS challenge in PBS-treated WT mice consistent with our previous observation that FoxM1 is induced only during the recovery phase following sepsis challenge [23, 25]. However, BMPC transplantation resulted in a marked induction of FoxM1 expression in WT lungs at 24h post-LPS challenge (Figure 1A, B). FoxM1 expression in BMPC-treated WT lungs remained elevated at 48h post-LPS challenge which was significantly greater than that of PBS-treated WT lungs. BMPC treatment failed to induce FoxM1 expression in FoxM1 CKO lungs, indicating that BMPC-induced FoxM1 expression in WT lungs is predominantly in endothelial cells.

Figure 1. Failure of BMPC to inhibit lung vascular permeability in FoxM1 CKO mice following LPS challenge.

(A) BMPC induction of FoxM1 expression in pulmonary vasculature of WT mice. At 2h post-LPS challenge (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), BMPC (0.2 × 106 cells/mouse) were administered to WT or FoxM1 CKO mice. The same volume of PBS was injected to a separate cohort of mice as controls. Lungs were collected at 0 (basal), 24 and 48h post-LPS for QRT-PCR analysis of FoxM1 expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4/group). *, P < 0.05 versus WT-0h; †, P < 0.001 versus WT-0h; ‡, P < 0.01 versus WT-PBS CKO, FoxM1 CKO. (B) Representative Western blots demonstrating BMPC-induced FoxM1 protein expression in WT lungs. At 24h post-LPS challenge, lungs were collected and lysed for Western blotting with anti-FoxM1 antibody. The same membrane was reprobed with anti-β-actin as loading control. (C) Representative micrographs demonstrating that BMPC inhibited lung vascular injury in WT mice but not in FoxM1 CKO mice. At 24h post-LPS challenge, mouse lungs 30 min after injection of EBA were perfused to remove blood and imaged. (D) Lung vascular permeability was measured by EBA extravasation assay at 24h and 48h post-LPS challenge. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4/group). *, P < 0.001 versus WT-PBS; †, P < 0.05 versus WT-0h (Basal); ‡, P < 0.05 versus WT-PBS-48h; **, P < 0.01 versus WT-BMPC-48h.

Endothelial FoxM1 expression is required for BMPC-induced decrease of lung vascular permeability

At 24 and 48h post-LPS challenge, mouse lungs were collected to quantify endothelial barrier function by assessing EBA extravasation, a measure of vascular permeability [25, 29]. We observed that LPS induced a marked increase of vascular leakage in PBS-treated WT mice whereas BMPC transplantation induced a drastic decrease of lung vascular permeability in WT mice 24h post-LPS challenge (Figure 1C, D). At 48h post-LPS challenge, lung vascular permeability in BMPC-treated WT mice was returned to basal level (Figure 1D). However, unlike the BMPC-treated WT mice, the EBA values in BMPC-transplanted FoxM1 CKO mice 24h post-LPS challenge was similar to those of PBS-treated FoxM1 CKO mice (Figure 1C, D). Similarly, 48h post-LPS challenge, the BMPC-mediated protective effects on vascular permeability seen in WT mice were also lost in FoxM1 CKO lungs. Vascular permeability in BMPC-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs remained significantly elevated 48h post-LPS challenge (Figure 1D). These data suggest that endothelial FoxM1 plays an essential role in the mechanism of BMPC-elicited protection from sepsis-induced lung vascular injury as well as restoration of lung vascular integrity.

BMPC-mediated resolution of lung inflammation is impaired in FoxM1 CKO mice

We next assessed lung inflammation by measuring MPO activity, an indicator of neutrophil infiltration [23, 30], as well as expression of proinflammatory genes. At 24h post-LPS, BMPC treatment resulted in a marked decrease of MPO activity in both WT and FoxM1 CKO lungs (Figure 2A). At 48h post-LPS challenge, MPO activity in BMPC-treated WT lungs were returned to basal levels. However, BMPC treatment failed to inhibit MPO activity in FoxM1 CKO lungs. Similar to PBS-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs, MPO activity in BMPC-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs remained markedly elevated (Figure 2A). QRT-PCR analysis revealed a drastic decrease of expression of proinflammatory genes at 24h post-LPS challenge in both WT and FoxM1 CKO lungs compared to PBS-treated controls (Figure 2B, C). At 48h post-LPS challenge, expression of these genes in BMPC-treated WT lungs was inhibited and returned to basal levels. However, BMPC treatment failed to inhibit the expression of these proinflammatory genes in FoxM1 CKO lungs, which was similar to or even greater than PBS-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs (Figure 2B, C). Together, these data suggest that BMPC-mediated inhibition of inflammation in the acute phase following LPS challenge is FoxM1-independent but BMPC-elicited resolution of lung inflammation requires endothelial expression of FoxM1.

Figure 2. Impaired resolution of lung inflammation by BMPC in FoxM1 CKO mice.

(A) MPO activity demonstrating that BMPC promoted resolution of lung inflammation in WT mice but not in FoxM1 CKO mice. At 2h post-LPS challenge (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), BMPC or PBS were administered to WT or FoxM1 CKO mice. At 0 (basal), 24 and 48h post-LPS, mouse lungs were perfused free of blood and MPO activity was assayed. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4/group). *, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.05; ‡, P < 0.05 versus WT-48h; #, P < 0.05 versus WT-0h; **, P < 0.01 versus CKO-0h. Although BMPC treatment resulted in similar decreases of MPO activity in WT and FoxM1 CKO lungs at 24h post-LPS, BMPC promoted a rapid resolution of lung inflammation in WT lungs but not in FoxM1 CKO lungs during the recovery phase. (B, C) QRT-PCR analyses of expression of proinflammatory genes in mouse lungs. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4/group). *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01; ‡, P < 0.05 versus WT-48h; #, P < 0.05 versus WT-0h; **, P < 0.01 versus FoxM1 CKO-PBS-24h. BMPC transplantation resulted in diminished expression of proinflammatory genes in WT lungs at 48h post-LPS challenge. However, BMPC had little effect on the elevated expression of these proinflammatory genes in FoxM1 CKO lungs at 48h post-LPS.

BMPC fail to reduce mortality in FoxM1 CKO mice following LPS challenge

A previous study showed that BMPC promote survival in WT mice following LPS challenge [10]. To determine whether BMPC also promote survival in FoxM1 CKO mice as seen in WT mice, WT or FoxM1 CKO mice were challenged with a lethal dose of LPS (20 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by BMPC transplantation 2h post-LPS. PBS was administered as a control. As shown in Figure 3A, both control WT and FoxM1 CKO mice exhibited 100% mortality within 60h post-LPS whereas greater than 60% of the BMPC-treated WT mice survived within the same time period, and 50% of them survived for at least 5 days. However, BMPC-treated FoxM1 CKO mice died as quickly as PBS-treated control mice and less than 20% of them survived. Histological examination revealed severe inflammatory lung injury including massive sequestration of leukocytes and thickened alveolar septa in lungs of dying WT mice treated with PBS but not BMPC (Figure 3B). FoxM1 CKO mice, regardless of BMPC treatment, also exhibited severe infiltration of leukocytes and thick alveolar septa (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Loss of BMPC-elicited survival effects in FoxM1 CKO mice.

(A) BMPC failed to promote survival of FoxM1 CKO mice. At 2h post-LPS challenge (20 mg/kg, i.p.), BMPC (0.2 × 106 cells/mouse) or PBS (controls) were administered to WT or FoxM1 CKO mice. Mice were monitored for mortality for 4 days. n=8 mice/group. *, P < 0.001 versus FoxM1 CKO+BMPC. (B) Representative H & E staining showing severe inflammatory lung injury including massive sequestration of leukocytes and thickened alveolar septa in PBS-treated WT and FoxM1 CKO mice as well as BMPC-treated FoxM1 CKO mice but not WT mice. At 40–48h post-LPS challenge (20 mg/kg, i.p.), mouse Lungs were fixed in situ with 10% PBS-buffered formalin and processed for H & E staining. Br, bronchiole; V, vessel. Scale bar, 100 μm.

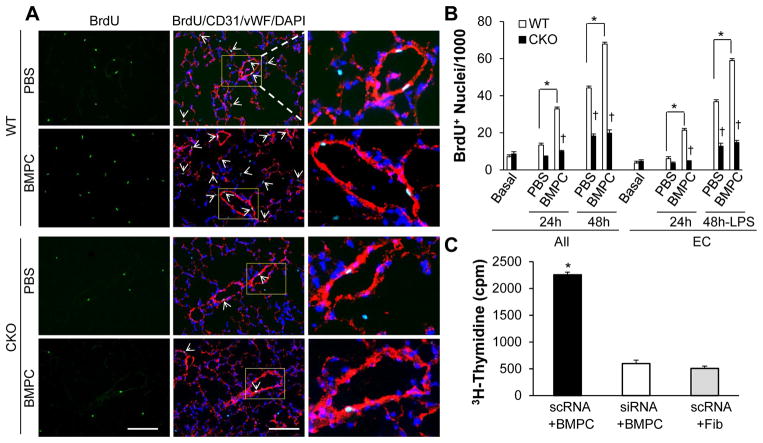

BMPC treatment induces FoxM1-dependent endothelial regeneration in WT lungs

Given that EC proliferation plays an important role in endothelial barrier repair following LPS-induced lung vascular injury [23, 25, 32], we next examined the rate of EC proliferation in mouse lungs. Cell proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation and EC were stained with endothelial markers CD31 and vWF. At 48h post-LPS challenge, BMPC-treated WT lungs exhibited a significant increase of EC proliferation compared to control PBS-treated WT lungs (Figure 4A, B). However, the rate of EC proliferation in PBS-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs was inhibited, and BMPC treatment failed to induce cell proliferation in FoxM1 CKO lungs. Consistent with previous findings [23, 25], the majority of proliferating cells in WT lungs were EC (Figure 4A, B).

Figure 4. BMPC-induced EC proliferation in mouse lungs.

(A) Representative micrographs demonstrating that BMPC-induced EC proliferation in WT lungs was inhibited in FoxM1 CKO lungs. At 48h post-LPS challenge (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), mouse lungs were collected for cryosectioning. Anti-BrdU antibody (green) was employed to immunostain proliferating cells while anti-vWF and −CD31 antibodies (red) were used to co-immunostain lung EC. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate proliferating (BrdU+) EC. Scale bar, 40μm. (B) Quantification of cell proliferation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4). *, P < 0.001 versus WT; †, P < 0.01. Approximately 40% of “All” cells counted were EC. Extravasating blood cells were also included in the count but in the “All” category (not “EC” category). BMPC treatment induced a drastic increase of EC proliferation in WT lungs but not in FoxM1 CKO lungs. (C) 3H-thymidine incorporation assay demonstrating that the BMPC-induced cellular proliferation seen in WT EC was inhibited in FoxM1-deficient EC. EC at 80–90% confluence were collected for transfection with either FoxM1 siRNA (siRNA) or scrambled RNA (scRNA) and then plated at low density on the bottom chamber of the transwell plate. At 48h post-transfection, BMPC or an equal number of fibroblasts (control) were added to the top chamber of the transwell plate. Proliferation of EC in the bottom chamber was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3 experiments). *, P < 0.001 versus siRNA+BMPC or scRNA+Fib. Fib, fibroblasts.

To further determine whether BMPC-induced lung EC proliferation is mediated by endothelial FoxM1, we employed siRNA to knockdown FoxM1 in primary cultures of human lung microvascular EC. Scrambled RNA (scRNA) was used as a control. As shown previously [23, 25], FoxM1 siRNA induced 90% knockdown of FoxM1 expression at 65h post-transfection (Supplemental Figure S2). Following transfection, human lung ECs were seeded in the lower chambers of 6-well transwell plates. At 60h post-transfection, BMPC maintained in the top chambers of the transwell plates were layered on top of human lung EC. Cell proliferation was then assessed by a 3H-Thymidine incorporation assay. As shown in Figure 4C, BMPC treatment induced a 4-fold increase of DNA synthesis in WT (scRNA-transfected) EC compared to FoxM1-deficient EC.

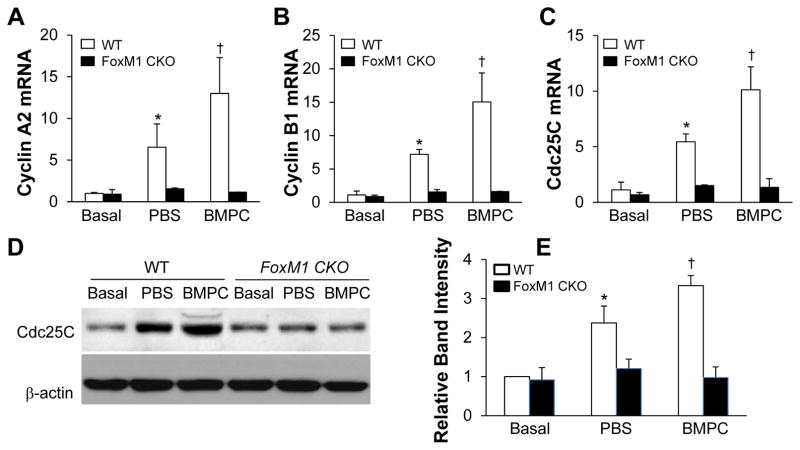

To gain insight into the molecular basis of BMPC-induced cell proliferation, we examined expression of the FoxM1 target genes essential for cell cycle progression. As shown in Figure 5, expression of Cyclins A2 and B1 as well as Cdc25C was markedly increased in BMPC-treated WT lungs compared to PBS-treated WT lungs at 48h post-LPS, which is consistent with marked induction of FoxM1 in BMPC-treated WT lungs (Figure 1A). However, expression of these genes was inhibited in PBS-treated control FoxM1 CKO lungs and BMPC treatment failed to induce expression of these genes in FoxM1 CKO lungs (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Marked increase of expression of FoxM1 target genes in BMPC-treated WT but not FoxM1 CKO lungs.

(A–C) QRT-PCR analysis demonstrating BMPC treatment potentiates expression of Cyclin A2 (A), Cyclin B1 (B) and Cdc25C (C) in WT but not FoxM1 CKO lungs. At 48h post-LPS challenge (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), lungs were collected for RNA isolation and QRT-PCR analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4/group). *, P < 0.001 versus WT-basal; **, P < 0.01 versus WT-PBS. Consistent with inhibited FoxM1 expression in FoxM1 CKO lungs, expression of its target genes was also inhibited in these lungs regardless of treatment. (D) Representative Western blots demonstrating a marked increase of Cdc25C expression in lungs of BMPC-treated WT mice at 48h post-LPS. Anti-β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) Bar graph representation of Cdc25C band intensity normalized to β-actin. The normalized band intensity of WT-basal was set at 1. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). *, P < 0.001 versus WT-basal; †, P < 0.05 versus WT-PBS.

BMPC enhances endothelial barrier function through the FoxM1-β-catenin axis

To delineate the mechanism of BMPC in regulating endothelial barrier function, we employed a transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) assay to quantify time-dependent changes in the integrity of endothelial junctions. Human lung microvascular EC grown at 80–90% confluence were collected for transfection with either FoxM1 siRNA or scRNA, and then plated at confluence on gold electrodes to form cell–to-cell contacts and intact monolayers before the induction of FoxM1 deficiency by siRNA [24]. At 65h post-transfection, both FoxM1-deficient and WT endothelial monolayers exhibited similar basal barrier function, as assessed by TER. Upon addition of BMPC, FoxM1 scRNA-transfected (WT) endothelial monolayers exhibited a rapid increase of resistance, indicative of enhanced endothelial barrier function (Figure 6A). However, there was no increase in TER values in the FoxM1-deficient endothelial monolayer following addition of BMPC (Figure 6A). Accordingly, we also observed enhanced junctional expression of VE-cadherin in BMPC-treated WT endothelial monolayers compared to PBS-treated WT endothelial monolayers (Figure 6B), indicating enhanced endothelial barrier function. BMPC treatment failed to enhance VE-cadherin expression in the junctions of FoxM1-deficient endothelial monolayers (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. BMPC enhancement of endothelial barrier function through the FoxM1-β-catenin axis.

(A) BMPC enhanced endothelial barrier function in WT but not in FoxM1-deficient EC. At 65h post-FoxM1 siRNA (siRNA) or scRNA transfection, BMPC in 50 ul PBS or the same volume of PBS was added to the EC monolayers. TER was monitored continuously for 3h. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3 experiments). *, P < 0.05 versus siRNA+PBS. BMPC induced a marked increase in TER in scRNA-transfected (WT) EC but not in FoxM1 siRNA-transfected (FoxM1-deficient) EC. (B) Representative micrographs demonstrating enhanced junctional expression of VE-cadherin in BMPC-treated WT (scRNA-transfected) endothelial cell monolayers. At 60h post-siRNA/scRNA-transfection, BMPC in 50 μl of PBS or the same volume of PBS was added to the EC monolayers. Two hours later, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for immunostaining with anti-VE-cadherin (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) Restoration of β-catenin expression in FoxM1-deficient EC normalized the TER resposne to BMPC treatment. Plasmid DNA expressing β-catenin (β-cat) or empty vector (Vector) was transfected to EC along with FoxM1 siRNA. TER was monitored for 3h following BMPC addition. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3 experiments). *, P < 0.05 versus either scRNA+Vector+BMPC or siRNA+1.5μg β-cat+BMPC; †, P < 0.05 versus siRNA+1.5μg β-cat+BMPC; ‡, P < 0.05 versus siRNA+Vector+BMPC. (D) Requirement of endothelial FoxM1 for S1P-mediated enhancement of endothelial barrier function. At 65h post-transfection, S1P (1.5 μM) was added to the monolayers and TER was monitored for 3h. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3 experiments). *, P < 0.01 versus other two groups.

Our published studies have shown that FoxM1 plays an important role in regulating re-annealing of endothelial junction complex through transcriptional control of β-catenin [24]. We next determined whether restoration of β-catenin expression in FoxM1-deficient EC will normalize the response to BMPC. Plasmid DNA expressing human β-catenin under the control of the CMV promoter was transfected to human lung microvascular EC along with FoxM1 siRNA (Supplemental Figure S3). As shown in Figure 6C, BMPC induced a similar increase of TER values in FoxM1-deficient endothelial monolayer transfected with 1.5 μg of β-catenin plasmid DNA as seen in WT monolayer. Furthermore, β-catenin expression normalized BMPC-elicited TER responses in FoxM1-deficient endothelial monolayer in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C). Together, these data demonstrate that endothelial FoxM1 is required for BMPC-induced enhancement of endothelial barrier function via β-catenin.

It has been shown that BMPC release sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) to enhance endothelial junction integrity [10]. We next determined whether S1P-mediated enhancement of endothelial barrier function requires endothelial expression of FoxM1. As shown in Figure 6D, S1P-induced increase of TER seen in WT human lung microvascular EC was inhibited in FoxM1-deficient EC. Restoration of β-catenin expression in FoxM1-deficient EC rescued the defective response to S1P treatment and the TER values were similar to those seen in WT EC.

Discussion

With the use of the unique mouse model of FoxM1 CKO mice, for the first time, we were able to demonstrate the requisite role of endothelial FoxM1 in mediating exogenous BMPC-elicited protection against LPS-induced inflammatory lung injury. We have shown that BMPC had no protective effects on LPS-induced inflammatory lung injury and mortality in FoxM1 CKO mice in contrast to WT mice. Similar to PBS-treated control FoxM1 CKO mice, BMPC-treated FoxM1 CKO mice exhibited a persistent increase of lung vascular permeability and impaired resolution of lung inflammation. Mechanistically, endothelial expression of FoxM1 is indispensable for BMPC-induced endothelial cell proliferation and enhancement of endothelial barrier function and thereby restoration of vascular integrity. Together, these data suggest that exogenous adult stem/progenitor cells function through endothelial FoxM1 to promote vascular repair and resolution of lung inflammation following sepsis challenge.

Mounting evidence has shown that bone marrow-derived adult stem cells such as mesenchymal stem cells and BMPC produce protective effects against lung injury in various animal models of ALI [10–16] as well as in an ex vivo perfused human lung model [17, 18]. Several studies have been performed to determine whether direct engraftment of these progenitor cells contributes to repair of the endothelium [33–36]. In all these studies, the engraftment rates of mesenchymal stem cells are very low if any engraftment occurs at all. Additionally, a recent study employing complementary approaches, including genetic lineage tracing, has failed to find any significant contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to maintenance and repair of the lung endothelium [37]. Given that the engraftment rates of these progenitor cells in lung endothelial monolayers are very low and the therapeutic effects are elicited within hours, it is believed that these cells exert protective effects against lung injury mainly through an indirect paracrine mechanism. Indeed, many paracrine mediators have been identified including IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist, keratinocyte growth factor, IGF-I, TSG-6, S1P, angiopoietin, bFGF and VEGF [14, 16, 20, 21, 38–41]. Through these humoral factors, bone marrow-derived progenitor cells have been shown to modulate immune cell function, reduce inflammation, inhibit vascular permeability, and promote survival. However, little is known about the endogenous mediators of these paracrine actions. Here, our studies have identified endothelial FoxM1 as a critical endogenous reparative factor to mediate the protective effects of BMPC on inflammatory lung injury.

We have shown that BMPC promotes EC proliferation in WT mouse lungs but not in FoxM1 CKO lungs. Employing the transwell culture system in which BMPC and EC were separated from one another by a permeable membrane, we observed that BMPC-induced cell proliferation seen in WT EC was inhibited in FoxM1-deficient EC. These data suggest that BMPC induce lung EC proliferation in a FoxM1-dependent manner through paracrine release of mitogenic factors. Several mitogenic factors including VEGF, bFGF, and angiopoietin-2 are identified in the MSC secretome [21, 40, 41]. Future study is warranted to determine whether BMPC also release similar angiogenic factors and thereby activate FoxM1 expression and promote EC proliferation. Although the resting pulmonary endothelium is quiescent [23, 42], other studies as well as our own studies have shown that EC proliferation is an important component of endothelial repair after injury [23, 25, 32]. FoxM1 CKO lungs exhibit impaired endothelial repair whereas overexpression of FoxM1 in FoxM1 transgenic mice promotes endothelial repair following inflammatory lung vascular injury [23, 25]. Here we observed that BMPC failed to promote endothelial repair and restoration of vascular integrity in FoxM1 CKO mice following LPS challenge. At 48h post-LPS, lung vascular permeability in BMPC-treated WT mice was returned to basal levels and lung inflammation was resolved as demonstrated by restoration of basal levels of MPO activity and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in these lungs. However, BMPC-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs exhibited a persistent increase of vascular permeability and lung inflammation 48h post-LPS as seen in PBS-treated FoxM1 CKO lungs, indicating impaired endothelial repair and resolution of lung inflammation. Intriguingly, we observed a similar inhibitory effect of BMPC on lung inflammation in WT and FoxM1 CKO mice 24h after LPS challenge, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory effect of BMPC during the injury/acute phase is independent of endothelial FoxM1. However, BMPC-induced rapid resolution of lung inflammation also requires endothelial expression of FoxM1. Thus, our data demonstrate that FoxM1-dependent EC proliferation plays an important role in BMPC-mediated vascular repair and resultant resolution of inflammation following inflammatory lung injury.

Besides regeneration of the injured endothelium, restoration of endothelial barrier function following lung vascular injury also requires re-annealing of the endothelial cell-to-cell contacts [24, 43]. Consistent with previous publications [10, 11], our data have shown that BMPC treatment induces a rapid increase in the transendothelial electrical resistance of monolayers, indicating enhanced endothelial barrier function in WT EC. However, BMPC treatment has no effects on the endothelial barrier function of FoxM1-deficient endothelial monolayers. Our previous study demonstrated that β-catenin, an integral protein constituent of endothelial adherens junction complexes is a transcriptional target of FoxM1 [24]. FoxM1-deficient EC exhibit decreased expression of β-catenin and impaired recovery of endothelial barrier function following thrombin-induced endothelial injury [24]. Intriguingly, our current study has shown that restoration of β-catenin expression in FoxM1-deficient EC normalized endothelial barrier responses to BMPC treatment. These data suggest that BMPC-elicited effects on endothelial barrier enhancement and re-annealing of endothelial cell-to-cell contacts are mediated by endothelial FoxM1 through β-catenin.

The phospholipid S1P, a serum-borne bioactive lipid mediator, regulates an array of biological activities in various cell types. In the mouse model of LPS-induced lung injury, S1P was shown to attenuate pulmonary vascular leakage [29, 44]. In EC, S1P through its receptors, S1P1 and S1P3, plays an important role in junction assembly and endothelial morphogenesis [45]. It has been shown that cultured BMPC are greater S1P producers than cultured EC [10]. BMPC-released S1P is responsible for their protective function in promoting endothelial junction integrity in vitro and in mice following LPS challenge [10]. Here we demonstrated that S1P-mediated enhancement of endothelial barrier function requires endothelial expression of FoxM1 and its transcriptional target β-catenin. These data suggest that endothelial FoxM1 is required for BMPC-mediated enhancement of endothelial barrier function through paracrine release of S1P.

In conclusion, our data have identified endothelial FoxM1 as a critical endogenous mediator of BMPC-induced protection against inflammatory lung injury. BMPC treatment induced rapid expression of FoxM1 in the pulmonary vasculature of WT mice, which in turn mediates BMPC-induced vascular repair through FoxM1-dependent EC proliferation and re-annealing of endothelial cell-cell contacts to restore vascular integrity and thereby promote resolution of lung inflammation and survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01HL085462, R01HL085462-3S1, R56HL085462, and P01HL077806 (project 4) to Y.Y. Z.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.D.Z: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript. X.H. collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript. F.Y., C.T., Z.Q., and K.T.: data collection, assembly, and analysis, and final approval of manuscript. Y.Y.Z.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosure: The authors indicate no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA, Esmon C, et al. Future research directions in acute lung injury: summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1027–1035. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-966WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, et al. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg NM, Steinberg BE, Slutsky AS, et al. Broken barriers: a new take on sepsis pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:88ps25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee WL, Slutsky AS. Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:689–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1007320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnham EL, Taylor WR, Quyyumi AA, et al. Increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells are associated with survival in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:854–860. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1325OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada M, Kubo H, Ishizawa K, Kobayashi S, Shinkawa M, Sasaki H. Increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with bacterial pneumonia: evidence that bone marrow-derived cells contribute to lung repair. Thorax. 2005;60:410–413. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.034058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao YD, Ohkawara H, Rehman J, et al. Bone marrow progenitor cells induce endothelial adherens junction integrity by sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:696–704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wary KK, Vogel SM, Garrean S, Zhao YD, Malik AB. Requirement of alpha(4)beta(1) and alpha(5)beta(1) integrin expression in bone-marrow-derived progenitor cells in preventing endotoxin-induced lung vascular injury and edema in mice. Stem Cells. 2009;27:3112–20. doi: 10.1002/stem.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao YD, Ohkawara H, Vogel SM, et al. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells prevent thrombin-induced increase in lung vascular permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L36–44. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00064.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta N, Su X, Popov B, et al. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179:1855–1863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mei SH, Haitsma JJ, Dos Santos CC, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reduce inflammation while enhancing bacterial clearance and improving survival in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1047–1057. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0010OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krasnodembskaya A, Samarani G, Song Y, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells reduce mortality and bacteremia in gram-negative sepsis in mice in part by enhancing the phagocytic activity of blood monocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L1003–1013. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00180.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeth K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JW, Fang X, Gupta N, et al. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of E. coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in the ex vivo perfused human lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16357–16362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907996106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JW, Krasnodembskaya A, McKenna DH, et al. Therapeutic effects of human mesenchymal stem cells in ex vivo human lungs injured with live bacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:751–760. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-0990OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danchuk S, Ylostalo JH, Hossain F, et al. Human multipotent stromal cells attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice via secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 6. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;2:27. doi: 10.1186/scrt68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasnodembskaya A, Song Y, Fang X, et al. Antibacterial effect of human mesenchymal stem cells is mediated in part from secretion of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2229–2238. doi: 10.1002/stem.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ionescu L, Byrne RN, van Haaften T, et al. Stem cell conditioned medium improves acute lung injury in mice: in vivo evidence for stem cell paracrine action. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L967–977. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00144.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam MN, Das SR, Emin MT, et al. Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow-derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat Med. 2012;18:759–765. doi: 10.1038/nm.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao YY, Gao XP, Zhao YD, et al. Endothelial cell-restricted disruption of FoxM1 impairs endothelial repair following LPS-induced vascular injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2333–2343. doi: 10.1172/JCI27154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirza MK, Sun Y, Zhao YD, et al. FoxM1 regulates re-annealing of endothelial adherens junctions through transcriptional control of beta-catenin expression. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1675–1685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X, Zhao YY. Transgenic expression of FoxM1 promotes endothelial repair following lung injury induced by polymicrobial sepsis in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang IC, Chen YJ, Hughes D, et al. Forkhead box M1 regulates the transcriptional network of genes essential for mitotic progression and genes encoding the SCF (Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10875–10894. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10875-10894.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laoukili J, Kooistra MR, Bras A, et al. FoxM1 is required for execution of the mitotic programme and chromosome stability. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:126–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa RH. FoxM1 dances with mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:108–110. doi: 10.1038/ncb0205-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, et al. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1245–1251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1258OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirza MK, Yuan J, Gao XP, et al. Caveolin-1 deficiency dampens Toll-like receptor 4 signaling through eNOS activation. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2344–2351. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao YY, Sawyer DR, Baliga RR, et al. Neuregulins promote survival and growth of cardiac myocytes. Persistence of ErbB2 and ErbB4 expression in neonatal and adult ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10261–10269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Reilly MA. DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoints in hyperoxic lung injury: braking to facilitate repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L291–305. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kotton DN, Fabian AJ, Mulligan RC. Failure of bone marrow to reconstitute lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:328–334. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0175RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rojas M, Woods CR, Mora AL, et al. Endotoxin-induced lung injury in mice: structural, functional, and biochemical responses. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L333–341. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00334.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Haaften T, Byrne R, Bonnet S, et al. Airway delivery of mesenchymal stem cells prevents arrested alveolar growth in neonatal lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1131–1142. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0179OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gothert JR, Gustin SE, van Eekelen JA, et al. Genetically tagging endothelial cells in vivo: bone marrow-derived cells do not contribute to tumor endothelium. Blood. 2004;104:1769–1777. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohle SJ, Anandaiah A, Fabian AJ, et al. Maintenance and repair of the lung endothelium does not involve contributions from marrow-derived endothelial precursor cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:11–19. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi YH, Kurtz A, Stamm C. Mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac cell therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:3–17. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schinkothe T, Bloch W, Schmidt A. In vitro secreting profile of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:199–206. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, et al. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ezaki T, Baluk P, Thurston G, et al. Time course of endothelial cell proliferation and microvascular remodeling in chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:2043–2055. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64676-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szczepaniak WS, Zhang Y, Hagerty S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate rescues canine LPS-induced acute lung injury and alters systemic inflammatory cytokine production in vivo. Transl Res. 2008;152:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, et al. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 1999;99:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.