Key Points

Resolving, but not hyperinflammatory stimuli create a microenvironment conducive for the optimal development of adaptive immunity.

After onset and resolution, we introduce a third phase to acute inflammatory responses dominated by macrophages and lymphocytes.

Abstract

Acute inflammation is traditionally characterized by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) influx followed by phagocytosing macrophage (Mφs) that clear injurious stimuli leading to resolution and tissue homeostasis. However, using the peritoneal cavity, we found that although innate immune-mediated responses to low-dose zymosan or bacteria resolve within days, these stimuli, but not hyperinflammatory stimuli, trigger a previously overlooked second wave of leukocyte influx into tissues that persists for weeks. These cells comprise distinct populations of tissue-resident Mφs (resMφs), Ly6chi monocyte-derived Mφs (moMφs), monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Postresolution mononuclear phagocytes were observed alongside lymph node expansion and increased numbers of blood and peritoneal memory T and B lymphocytes. The resMφs and moMφs triggered FoxP3 expression within CD4 cells, whereas moDCs drive T-cell proliferation. The resMφs preferentially clear apoptotic PMNs and migrate to lymph nodes to bring about their contraction in an inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent manner. Finally, moMφs remain in tissues for months postresolution, alongside altered numbers of T cells collectively dictating the magnitude of subsequent acute inflammatory reactions. These data challenge the prevailing idea that resolution leads back to homeostasis and asserts that resolution acts as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity, as well as tissue reprogramming.

Introduction

Acute inflammation is characterized by the immediate and sequential release of proinflammatory mediators resulting in the influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). This early onset phase is followed by phagocytosing macrophage (Mφs) leading to leukocyte clearance and resolution.1 Although research has traditionally focused on identifying factors that drive inflammation, emphasis has now shifted toward this latter phase of resolution to understand how immune-mediated responses switch off. Results from these studies have advanced our understanding of PMN trafficking, efferocytosis, and proinflammatory leukocyte clearance, as well as immune-suppressive eicosanoids, specialized immune-regulatory cells, and cytokine catabolism.2-4 Such pathways terminate acute inflammatory responses and contribute to the notion that chronic inflammation/autoimmunity is avoided while homeostasis is reinstated.1 However, we now show that these sequential and overlapping events are only part of the pathophysiological importance of resolution and that resolution creates a microenvironment conducive for the optimal development of adaptive immunity. Moreover, we present data showing that months after resolution has occurred tissues do not revert back to their preinflamed state in terms of cellular composition and phenotype. Instead, a state of “adapted homeostasis” is achieved, which impacts the severity of subsequent inflammatory responses.

Thus, after onset and resolution, we now introduce a third, postresolution phase to the acute inflammatory response dominated by macrophages and lymphocytes. These data provide a new perspective on innate immunity by highlighting the significance of proresolution processes in establishing adaptive immunity and in long-term tissue reprogramming.

Materials and methods

Animal maintenance, cell labeling, and adoptive transfer studies

Male C57Bl6/J, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)−/−, and ccr2−/−5 were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, whereas CX3CR1GFP/+6 mice were a gift from Sussan Nourshargh, The William Harvey Research Institute. Mice were maintained in accordance with United Kingdom Home Office regulations. Peritonitis was induced by the intraperitoneal injection of 0.1, 10 mg/mouse zymosan A or 50 000 Streptococcus pneumoniaeova/mouse; S pneumoniaeova was obtained from Dr. Krzystof Trzcinski and Dr Marc Lipsitch, Harvard School of Public Health. PKH26-PCLred or PKH26-PCLgreen (2 mL of 500 nM; Sigma) were injected intraperitoneally at time points indicated in “Results.” MC-21 (250 µL) was injected subcutaneously on days 3, 5, and 7, with mice analyzed on day 9 after zymosan. For adoptive transfer of tissue-resident macrophages Mφs (resMφs) from wild-type (WT) mice to iNOS−/−, WT mice bearing a 0.1 mg of zymosan-induced peritonitis were injected with PKH26-PCL intraperitoneally at 72 hours. Three hours later, PKH26-PCL positive resMφs (gated as in “Results”) were isolated and 4 × 106 injected into iNOS−/− mice bearing a 0.1 mg of zymosan-triggered inflammation; spleen or lymph nodes were taken off on day 14 for immunohistochemistry. Delayed type hypersensitivity was established as previously described.5

Flow cytometry, cell sorting and immunohistochemistry

Flow cytometry and cell sorting was done on the LSR-II/LSR-Fortessa and FACSAria (BD Biosciences), respectively. Cells were incubated with Fc-Blocker (AbD Serotec) and fluorescent-labeled antibodies. Data were analyzed with FlowJo 7.0.1 software (Tree Star) using fluorescence minus one controls as the reference for setting gates. Antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (F4/80, CD11b, CD11c, Ly6c, Ly6g, Gr1, CD3, CD19, CD4, CD8, CD25, FoxP3, CD62l, CD44, CD115, major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II, Siglec-F, CD117, and CD49d). Immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen sections fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes before staining.

Uptake of apoptotic PMNs in vivo

Human PMNs were labeled with 5 µM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes; Life Technologies) and aged for 48 hours (80% apoptotic, as determined by annexin V/PI labeling). The 5 × 106 CFSE-labeled apoptotic PMNs were injected intraperitoneally into mice bearing a 24-hour or 72-hour peritonitis elicited by 0.1 mg of zymosan; these mice were previously injected with PKH26-PCLKred to distinguish resident from infiltrating monocyte-derived Mφs (moMφs), as detailed in “Results.” Mice were killed after 3 hours and exudates were collected for flow cytometry.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay

Spleens were taken from C57/Blk6J, crushed, and passed through a 70-µm cell strainer followed by a 35-µm cell strainer. Red blood cells were lysed in ACK lysis buffer (Enzo Life Sciences). Spleenocytes were purified using Miltenyi Biotec CD4+ T-cell isolation kit II and labeled with 5-µM CFSE (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies). CD4+/CFSE+ cells were seeded at 200 000 cells/well in RPMI 1640 containing penicillin/streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies), 30 U/mL rIL-2 (Miltenyi), and 200 000 CD3/28 beads (T-cell activation/expansion kit; Miltenyi). Then 60 000 resMφs or myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) were added. After 3 days, lymphocytes were stained with 10 µg/mL 7AAD and proliferation measured using the LSRFortessa.

Generation of Tregs

Transgenic CD4+ T cells expressing I-Ab restricted T-cell receptor recognizing tyrosinase related protein-1 (Trp-1) were isolated by magnetic bead sorting from Treg-depleted Foxp3-DTR-Trp-1 transgenic mice previously treated with diphtheria toxin. They were cocultured with moMφs, resMφs, or monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) for 5 days with Trp-1 peptide (SGHNCGTCRPGWRGAACNQKILTVR) + transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and analyzed for the presence of Foxp3+ cells by flow cytometry.

Antigen-presentation assays

Bone marrow was flushed using a 26 g needle with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium + l-glutamine, fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin and N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid. Cells were filtered and seeded onto a petri dish at 1 × 106 cells/mL in the above media supplemented with 20 ng granulocyte macrophage–colony stimulating factor and IL-4; media and growth factors were replenished on day 4. On day 7, dendritic cells were plated at 60 000 cells/well. At 60 000, moMφ, resMφ, and moDCs (from day 9 on 0.1 mg of zymosan) were sorted according to the gating strategy described in “Results,” and along with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells, were pulsed overnight with 20 nM ovalbumin (OVA)323-339 and 100 ng lipopolysaccharide (Sigma). These cells were then washed and incubated with CFSE-labeled CD4 T cells. After 4 days cells were stained with anti-CD4 and 7AAD and processed on the LSRFortessa. For the determination of lymphocyte proliferation from resolving bacterial peritonitis, sorted cells were pulsed overnight with 100 ng/mL LPS only, whereas bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were pulsed with 100 ng/mL LPS and OVA.

Results

Postresolution monocytes/Mφs in resolving inflammation

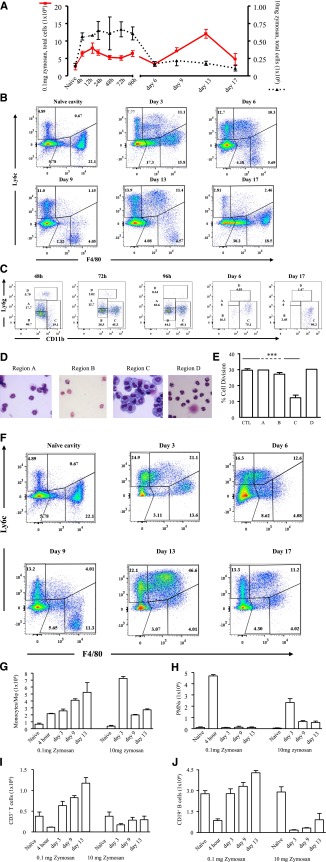

Low-dose zymosan (0.1 mg) caused a transient peritonitis peaking at around 12 hours (onset) followed by cell clearance (Figure 1A) . In contrast, injecting 10 mg of zymosan caused a more severe response that lasted up to day 5 (Figure 1A) and was associated with systemic inflammation.6 Alhough inflammation after 0.1 mg of zymosan had resolved (as defined by reduced total cell numbers) from day 6, there was another wave of cell influx into the peritoneum that was not observed after 10 mg of zymosan (Figure 1A). Polychromatic flow cytometry analysis revealed Ly6cint/F4-80int cells from 24 hours, followed by F40/80hi Mφs from day 6 (Figure 1B). In resolving inflammation, we also noticed a population of cells expressing Ly6g and/or CD11b (Figure 1C), comprising a mixture of PMNs and eosinophils (region A), eosinophils (region B), F4/80hi monocytic cells (region C), and mature PMNs (region D). Cells in region C persisted throughout resolution, and possessed abundant cytoplasm and a ring-like nuclear structure7 (Figure 1D), which along with their ability to inhibit T-cell proliferation (Figure 1E) and cell surface markers (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site) suggest that they are MDSCs. In contrast, in response to 10 mg of zymosan, monocyte/macrophage populations appeared more homogeneous, expressing Ly6c+/F4-80+ and F4/80+ from day 6 onward (Figure 1F), with a phenotype contrasting dramatically with Mφs and MDSC that infiltrated into postresolving tissues (supplemental Figure 2). The temporal profiles of monocyte/Mφ populations andPMNs are shown in Figure 1G-H.

Figure 1.

Inflammation in response to low- vs high-dose zymosan in the mouse peritoneum. (A) Either 0.1 or 10 mg of zymosan was injected into the peritoneal cavity of separate groups of mice. (B) Polychromatic flow cytometry is shown carried out on inflammation driven by 0.1 mg of zymosan, highlighting monocyte/macrophage populations, whereas (C) depicts, among other cells types MDSCs, alongside their (D) histological appearance and ability to (E) suppress T-cell proliferation. (F) In contrast, flow cytometry is shown carried out on inflammation driven by a more aggressive dose of 10 mg of zymosan, highlighting monocyte/macrophage populations, whereas (G-H) summarizes the relative temporal profiles of monocyte/macrophages andPMNs in these 2 models. (I-J) Profiles of lymphocytes are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 8 mice/group. ***P < .005.

Postresolution lymph node expansion and the accumulation of T and B cells

We also detected an increase in lymphocytes in the resolving peritoneum (0.1 mg of zymosan). Importantly, these cells were quantitatively fewer in inflammation driven by 10 mg of zymosan (Figure 1I-J). Using the gating strategy in supplemental Figure 3A, we detected an increase in monocyte-derived cells (moMφs and moDCs) in mesenteric lymph nodes between day 6 and day 13 (supplemental Figure 3B). These cells were classified as R1 (CD11c+ most likely plasmacytoid dendritic cells [pDCs]), R2 (CD11c+/CD11b+ resident and migratory DCs), R3 (CD11b Mφs), and R4 (monocytes). Lymph node expansion (supplemental Figure 3B) was associated with increased peripheral blood proliferating T and B lymphocyte numbers (supplemental Figure 3C), along with an accumulation of these cells in the peritoneum including Tregs, memory (CD44hi/CD62lo), and effector (CD44lo/CD62hi) CD4 and CD8 T cells and populations of B1a-, B1b- and B2-B cells (supplemental Figure 3D).

Hence, resolving inflammation is now characterized into 3 phases including onset (up to 12 hours), resolution (24-72 hours), and a third postresolution phase of monocytes/Mφ and MDSCs alongside lymphocyte infiltration occurring from day 6.

Origin of postresolution phase Mφs

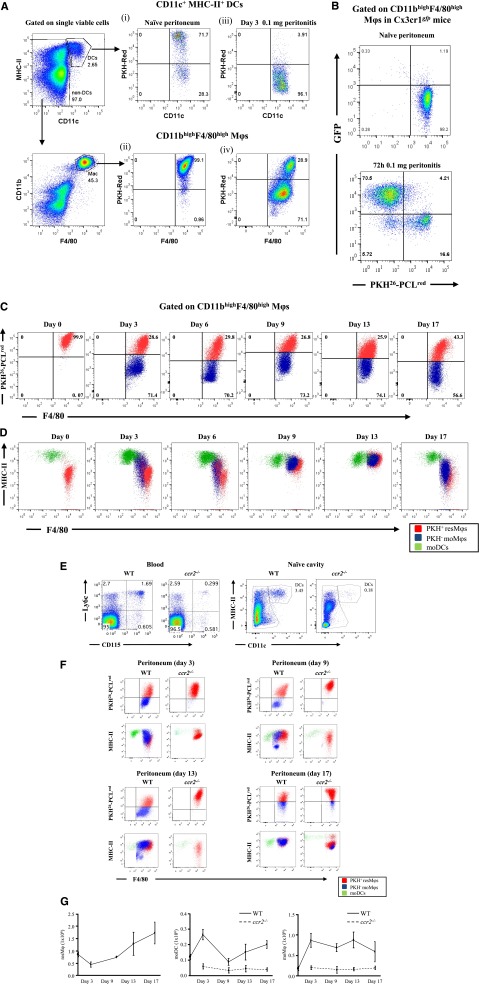

We used the gating strategy in supplemental Figure 4 to distinguish Mφs from dendritic cells (DCs) in the naïve peritoneum.8 Naive mice were injected with PKH26-PCLred, which preferentially labeled more than 70% of peritoneal DCs and 99.1% CD11bhi/F4-80hi positive, so-called large peritoneal Mφs, Figure 2Ai-ii, respectively. Then 0.1 mg of zymosan was injected into mice given PKH26-PCLred 1 hour earlier and inflammation was allowed to progress for 72 hours. Only 3.91% of PKH26-PCLred-positive DCs were found in the cavity at this time (Figure 2Aiii), indicating that these cells disappeared upon stimulation. However, there was the appearance of PKH26-PCLred-negative (96.1%) DCs, suggesting the infiltration of blood-derived DCs (Figure 2Aiii). In contrast, approximately 30% of CD11bhi/F4-80hi Mφs labeled positively for PKH26-PCLred indicating that these cells were peritoneal-resident Mφs and the remaining 71.1% unlabeled cells were moMφs (Figure 2Aiv). To confirm this, zymosan was injected into CX3CR1gfp/+ mice whose peritoneal Mφs were pre-labeled with PKH26-PCLred. In heterozygous CX3CRgfp/+ mice, 1 allele for the gene encoding CX3CR1, the receptor for fractalkine (CX3CL1), has been replaced with the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP), resulting in all circulating monocytes cells labeling positively for GFP.9 At 72 hours post-zymosan, 30% to 40% of CD11bhi/F4-80hi Mφs were positive for PKH26-PCLred, whereas 60% to 70% were only GFPpos (Figure 2B). These data show that during resolution (72 hours) both resident and blood monocyte-derived cells occupy the peritoneum, a trend maintained up to day 17 (Figure 2C). Back-gating these populations (resident Mφs, mMφs, and DCs) revealed the altering expression of MHC-II on these cells (Figure 2D) and confirmed that although resident DCs disappeared within a few hours of stimulation (Figure 2Aiii), they are replaced by infiltrating DCs.

Figure 2.

Temporal profiles of mononuclear phagocytes and DCs throughout inflammation, resolution, and postresolution/adaptive immunity phase. The gating strategy in supplemental Figure 4 was used to identify Mφ and DC populations in the peritoneal cavity of naïve mice. Using this approach, (A) the cell tracker dye PKH26-PCLred was injected into the cavity of mice and its labeling of tissue-resident DCs and resMφ determined in the naïve peritoneum (A, panels i-ii, respectively). These mice were then injected with 0.1 mg of zymosan, revealing (A, panel iii) the disappearance of DCs from the naïve peritoneum after inflammation and the presence of both (A, panel iv) PKH26-PCLred-positive resMφs and PKH26-PCLred-negative moMφs 72 hours post-zymosan. The origin of the latter as being Ly6chi-derived was confirmed using (B) CX3CRgfp mice. (C) The temporal and relative changes of resMφs vs moMφs (Ly6chi–monocyte-derived) from onset (4 hours), classic resolution (48-72 hours) and postresolution from day 6 onwards are shown. These data were further back-gated onto (D) MHC-II vs F4/80 to depict the overall temporal changes of mononuclear phagocytes and DCs throughout and after resolving inflammation. Further experiments were carried out using (E-F) ccr2−/− mice to prove the ly6chi origin of moMφs and MoDCs throughout resolution and postresolution with the (G) temporal profiles of resMφs, moMφs, and MoDCs shown. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 6 mice/group.

The majority of Ly6chi monocytes are retained within the bone marrow of ccr2−/− mice,10 resulting in substantially reduced numbers of these cells in blood (Figure 2E). Indeed, numbers of MHCII+ CD11c+ cells in the naive peritoneum of ccr2−/− mice were also substantially reduced, suggesting that the vast majority of peritoneal DCs are Ly6chi-derived (Figure 2E). Injecting 0.1 mg of zymosan into ccr2−/− mice confirmed the data, obtained with dye-tracking experiments and CX3CR1gfp/+ mice, that virtually no Ly6chi moMφs were detectable in ccr2−/− mice from days 3 to 17, whereas DCs numbers were reduced (Figure 2F).

Collectively, these experiments show that there is a third and more prolonged postresolution phase, subsequent to inflammatory onset and resolution, comprising tissue-resident Mφs, Ly6chi moMφs, and DCs, hereafter referred to as resMφs, moMφs, and moDCs, respectively. The temporal profile of these cells in WT vs ccr2−/− is shown in Figure 2G.

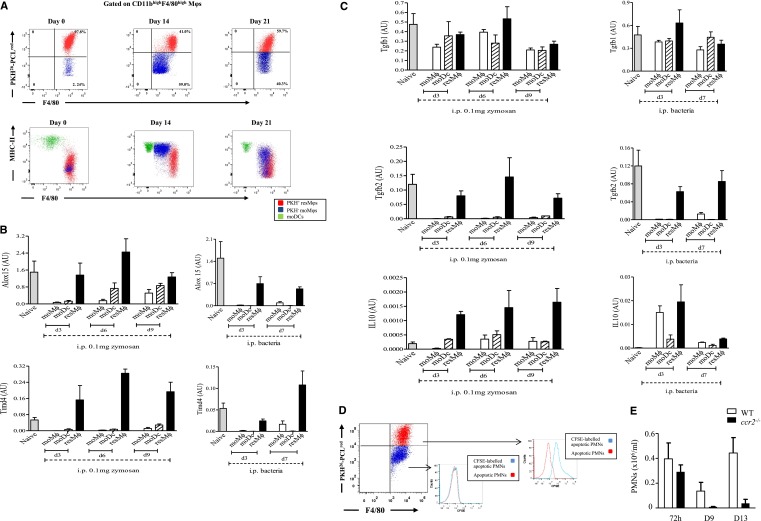

The resMφs phagocytose apoptotic PMNs and bring about postresolution lymph node contraction in an iNOS-dependent manner

Injecting OVA-labeled S pneumoniaeova intraperitoneally resulted in a similar profile of resMφs, moMφs, and moDCs to that seen with zymosan (Figure 3A). Indeed, memory T cells were seen to accumulate in the peritoneum after PMN clearance and proliferated specifically to bone marrow-derived DCs loaded with OVA (supplemental Figure 5). We sorted postresolution-phase Mφ populations from S pneumoniaeova and 0.1 mg of zymosan-driven inflammation, and subjected them to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for gene products previously determined by transcriptomic/bioinformatic analysis to be highly expressed in resolution-phase Mφs.11 TIMD4 (receptor for PS, which is expressed on apoptotic cells12) and ALOX15 (secretion of lipids that facilitate phagocytosis of apoptotic cells13,14) were primarily expressed in PKH26-PCLred-labeled resMφ from both models (Figure 3B). Indeed, TGF-β and IL-10, which were upregulated in Mφs during phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs, were also expressed in these cells (Figure 3C). Injecting CFSE-labeled apoptotic PMNs into mice, bearing 0.1 mg of zymosan-induced peritonitis previously injected with PKH26-PCLred, demonstrated that resMφs preferentially phagocytosed apoptotic PMNs during resolution (Figure 3D). It was confirmed that blood moMφs were not involved in the clearance of apoptotic PMNs in ccr2−/− mice, which showed no accumulation of PMNs up to day 13 (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Aspects of resolution-phase Mφ phenotype are conserved between sterile and infections resolving inflammation. (A) The temporal profile in resMφs, moMφs, and DCs are shown throughout the inflammatory and postresolution response to S pneumoniae. These cells, as well as the equivalent population from 0.1 mg of zymosan, were shown (B-C) FACSorted and subjected to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Injecting CFSE-labeled apoptotic PMNs into the peritoneum 48 hours post 0.1 mg of zymosan confirmed that (D) resMφs preferentially phagocytosed apoptotic PMNs with a little role for moMφs in this process; data confirmed using (E) Ly6chi-deficinet ccr2−/− mice showing no buildup of PMNs in the cavity postresolution. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 6 mice/group. i.p., intraperitoneal.

The resMφs were also enriched for iNOS (Figure 4A) and arginase (Figure 4B) with iNOS expressed in vesicles in postresolution resMφs (Figure 4C). Consistent with an immune suppressive phenotype, resMφs suppressed T-cell proliferation in an iNOS-dependent manner15 (Figure 4D). Taking this further, we found PKH26-PCLred-positive resMφs in the mesenteric lymph node and spleen on day 9 post-zymosan, located in both the T and B cell areas (Figure 4E). The presence of these immune-suppressive cells in lymphoid organs suggested a role in lymph node contraction seen from day 13 onward(supplemental Figure 3B). Indeed, although there were equivalent numbers of CD3- and CD19-positive T and B cells in the naive cavity of WT and iNOS−/− mice (Figure 4F), there were increased numbers of these cells in the peritoneum (Figure 4G) and spleen (Figure 4H) of iNOS knockouts 14 days post-zymosan; these were effects that persisted up to 6 weeks (Figure 4I). This increase in T and B cells was reversed by adoptively transferring PKH26-PCLred-positive resMφs taken from WT mice bearing a resolving inflammation and transferred into iNOS−/− bearing zymosan peritonitis (Figure 4G-H) with resMφsWT found in the spleen on day 14 (Figure 4J).

Figure 4.

The resMφs bring about postresolution lymphocyte contraction in an iNOS-dependent manner. The resMφs from 0.1 mg of zymosan and S pneumonia-induced acute resolving inflammation revealed increased expression of (A) iNOS and (B) arginase. (C) Immunofluorescence was used to visualize the intracellular localization of iNOS in postresolution resMφs, whereas (D) confirmed their iNOS-dependent suppression of T-cell proliferation. (E) Some PKH26-PCLred-positive resMφs migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes and spleen day 9 post 0.1 mg zymosan. Migrated iNOS-expressing resMφs mediate immune suppression was illustrated in iNOS−/− mice, although the composition of the (F) naïve cavity is equivalent between knockouts and controls, and 14 days after inflammation lymphocyte numbers were greater in iNOS−/− mice (G) peritoneal cavity and (H) spleens with (I) effects in persisting in spleen for up to 6 weeks. (G-I) The reversal of adaptive immune responses in iNOS deficient animals by the intraperitoneal injection of PKH26-PCLred-positive resMφ from WT mice into iNOS−/− mice are shown. (J) Adoptively transferred resMφs (stained red) from WT mice migrated to the spleen of iNOS knockouts; CD3 cells are stained in green. The P value was ≤.05, as determined by ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni t test or two-tailed Student t test, with data expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 6 mice/group. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

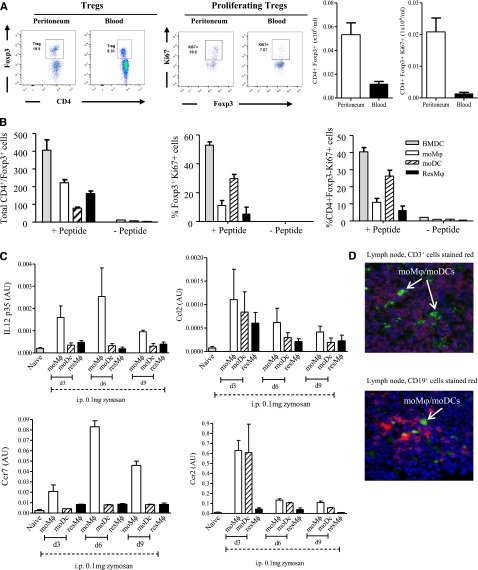

The resMφs and moMφs generate FoxP3 expression, whereas MoDCs trigger T-cell proliferation

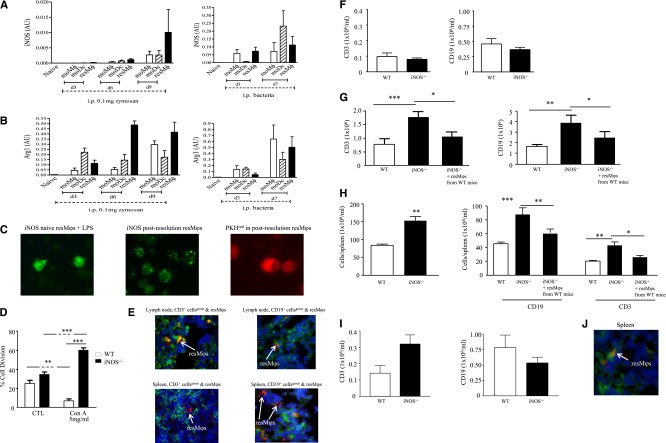

The resMφs, moMφs, and moDCs from both S pneumoniae and zymosan-triggered inflammation revealed increased expression of CD74 (HLA class II histocompatibility antigen γ chain), H2Aa (histocompatibility 2, class II antigen A, and α), and Clec2i on all 3 populations (supplemental Figure 6A). Despite these findings and data showing that monocyte-derived cells from S pneumoniae-injected mice bear a TipDC-like phenotype (supplemental Figure 6A for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and Figure 4A for iNOS anddata presented in Figure 2, namely CD11c/MHC-II expression on moMφs and moDCs), incubating all 3 Mφ populations from S pneumoniae and zymosan-treated mice overnight with OVA/LPS did not stimulate CD4 T cells from OT-II mice in comparison with bone marrow-derived DCs (supplemental Figure 6B). However, the accumulation of Tregs in the peritoneum peaking 9 days after zymosan with FoxP3 and Ki67 expression was greater than that seen within peripheral blood CD4 cells (Figure 5A) and lead us to investigate whether postresolution Mφs enrich for local Tregs. To test this, we incubated resMφ, moM, and moDCs with CD4 T cells with and without TGFβ/Trp1 peptide. The resMφs and moMφs triggered FoxP3 expression within CD4 T cells, whereas moDCs caused Tregs and CD4+/FoxP3− effector T cells to proliferate (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Postresolution Mφs trigger FoxP3 expression in CD4 T cells. (A) The relative ratios of blood vs peritoneal Tregs was determined 9 days after zymosan injection (0.1 mg) with postresolution resM, moMφs, and moDCs incubated with CD4 T- and Trp-1 peptide (SGHNCGTCRPGWRGAACNQKILTVR) + TGF-β for 5 days and analyzed for the presence of (B) Foxp3 expression and effector T-cell proliferation. Analysis of these Mφ/DC populations revealed a (C) migratory phenotype that was (D) confirmed by injecting PKH26-PCLgreen into mice on day 6 post-zymosan (0.1 mg), which also had PKH26-PCLred injected into their naïve peritoneum to label resMφs. This resulted in infiltrating moMφs and moDCs labeling positively for only PKH26-PCLgreen (shown), whereas resMφs were labeled with both PKH26-PCLred and PKH26-PCLgreen (not shown). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 6 mice/group.

Further analysis of resMφs, moMφs, and moDCs suggest that not only are their phenotypes similar between zymosan and bacterial infection, but that moMφ and moDCs expressing CCR2, CCR7, and CCL2 (Figure 5C) may also possess a migratory capacity. We tested this by injecting PKH26-PCLgreen into mice on day 6 post-zymosan (0.1 mg), which also had PKH26-PCLred injected into their naïve peritoneum to label resMφs. This resulted in infiltrating blood moMφs and moDCs labeling positively for only PKH26-PCLgreen, whereas resMφs were labeled with both PKH26-PCLred and PKH26-PCLgreen. Analysis of mesenteric lymph nodes on day 9 post-zymosan revealed the presence of PKH26-PCLgreen-labeled cells among the CD3+ and CD19+ positive lymphocyte populations (Figure 5D).

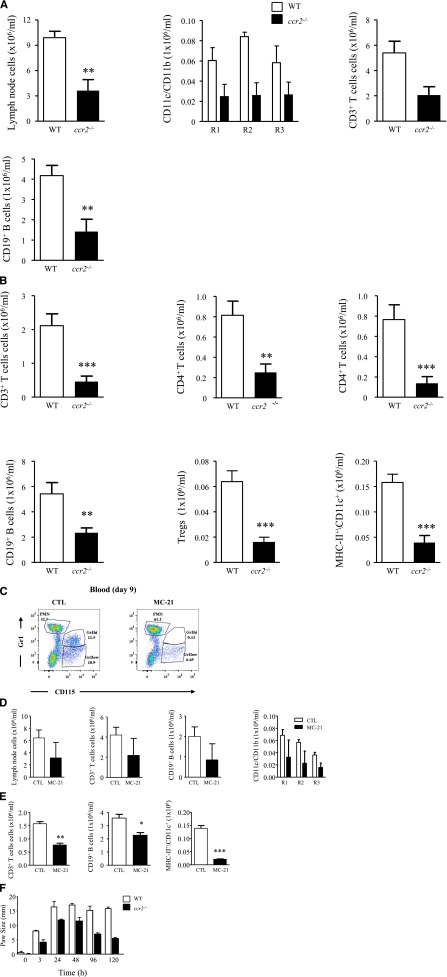

Postresolution T- and B-cell expansion is dampened in ccr2−/− mice and by CCR2 antibody

We wished to determine whether monocyte-derived cells specific to resolving inflammation bridges the gap between acute inflammation and adaptive immunity. Therefore, 0.1 mg of zymosan was injected into ccr2−/− mice. Not only was there a significant reduction in the number of cells within R1, R2, and R3 in lymph nodes of these animals (Figure 6A), but there was also a significant reduction in lymph node (Figure 6A) and peritoneum (Figure 6B) CD3 and CD19 lymphocytes on day 9 compared with WTs. Importantly, these effects arose from eliminating Ly6chi monocyte-derived resident DCs (MHC-II+/CD11c+) and postresolution Ly6chi-derived moMφs and moDCs. To discern the relative contribution of tissue-resident DCs from postresolution moMφs and moDCs to lymph node expansion, we used MC-21, which depletes Ly6chi monocytes.16 MC-21 was given therapeutically every second day starting on day 3 post-zymosan (0.1 mg) and was found to deplete blood Ly6C+ monocytes on day 9 post-zymosan (Figure 6C). MC-21 also caused a reduction in lymph node CD3 and CD19 cells and R1, R2, and R3 (Figure 6D), and peritoneal T- and B-cell numbers (Figure 6E). These effects were not as pronounced as that observed with ccr2−/− mice, reflecting the relative contribution of Ly6chi monocyte-derived cavity-resident DCs vs postresolution moMφs and DCs to lymph node expansion. To attribute a functional role to postresolution moMφs and moDCs, ccr2−/− mice bearing a delayed type hypersensitivity were found to have a dampened adaptive immune reaction compared with WT mice (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Postresolution adaptive immunity is dampened in ccr2−/− mice and with therapeutic depletion of postresolution Ly6chi monocyte. Zymosan (0.1 mg) was injected into ccr2−/− mice after a determination of (A) mesenteric lymph node CD11c+ DCs (R1), CD11c+/CD11b+ Mφs (R2), and CD11b+ Mφs (R3), as well as CD3 and CD19 T and B cells on day 9. (B) The corresponding distribution of lymphocyte populations in the peritoneum at the same time point is shown. MC-21 was given to WT mice 3 days after zymosan, and its effect on (C) Ly6chi monocyte populations was determined in the blood of naive animals and (D) mesenteric lymph node lymphocyte and Mφs/DCs alongside (E) lymphocytes and Mφs/DCs in the peritoneum day 9 post-zymosan injection (0.1 mg). (F) Reduced inflammation in ccr2−/− mice bearing a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction is shown. The P value was ≤.05, as determined by ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni t test or two-tailed Student t test, with data expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 6 mice/group. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

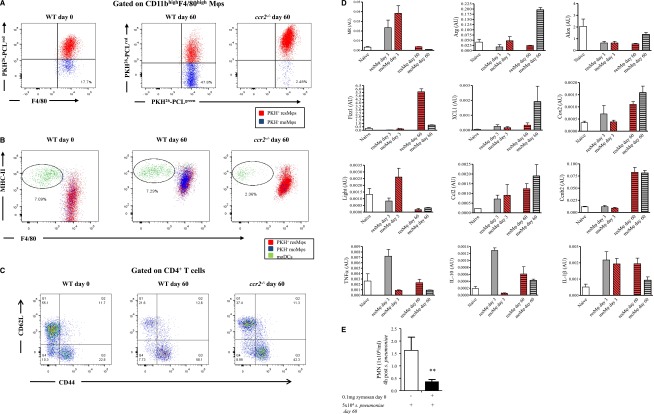

Resolving inflammation alters peritoneal cellular composition and phenotype

PKH26-PCLred was injected into the naïve cavity to label resident cells. This was followed 2 hours later by 0.1 mg of zymosan intraperitoneally. Seven days after the zymosan injection, then PKH26-PCLgreen was injected. This resulted in resMφs labeling with both PKH26-PCLred and PKH26-PCLgreen, but with postresolution moMφs and moDCs labeling with only PKH26-PCLgreen. Examination of the cavity 60 days post-zymosan detected a population of infiltrating PKH26-PCLgreen Ly6chi-derived moMφs whose numbers were reduced in ccr2−/− mice as expected (Figure 7A). In contrast, moDCs were unchanged in WT mice compared with naïve controls, but were also reduced in ccr2−/− mice (Figure 7B). We found an increase in effector CD4 T cells (Figure 7C) whose presence in the cavity was partially dependent on Ly6chi-derived moMφs as numbers of CD44+/CD62L- CD4 T cells were partly reversed in ccr2−/− mice (Figure 7C). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting on day 60 Ly6chi PKH26-PCLgreen moMφs and PKH26-PCLred/green resMφs revealed that both populations were phenotypically distinct from one another (Figure 7D). Indeed, the phenotypes of these cells on day 60 post-zymosan were also different to their phenotypes at 0 hours (resMφs) and 72 hours (resMφs and moMφs), respectively (Figure 7D). To determine the significance of these findings in terms of responses to secondary infection and/or injury, 60-day zymosan peritonitis mice were given S pneumoniae and inflammation was determined 4 hours later. Responses to S pneumoniae were dampened compared with mice that were not previously injected with zymosan 60 days earlier in terms of PMN numbers (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

A state of adapted homeostasis is experienced after resolving inflammation. PKH26-PCLred was injected into the cavity of naïve WT and ccr2−/− mice followed 2 hours later by 0.1 mg of zymosan. Six days after zymosan PKH26-PCLgreen was injected to distinguish resMφs (PKH26-PCLgred and PKH26-PCLgreen) from infiltrating moMφs/DCs (PKH26-PCLgreen only). The peritoneal cavity of these mice was examined 60 days after the initial zymosan injection revealing (A) a population of moMφs that were PKH26-PCLgreen, but were absent in ccr2−/− mice alongside (B) moDC numbers and (C) T-cell activation markers. (D) The resMφs and moDCs were FASCsorted for phenotypic analysis, whereas (E) the impact of postresolution altered homeostasis to a second hit of S pneumonia was determined on day 60. The P value was ≤.05, as determined by ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni t test or two-tailed Student t test, with data expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 6 mice/group. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Discussion

We show that there is a previously overlooked third phase of leukocyte influx into tissues after onset and resolution of acute inflammation. These cells comprise Ly6chi-derived moMφs, moDCs, and MDSCs. In addition, tissue-resident (prenatal-derived17-19) resMφs that disappear during the early phase of the inflammatory response,20 reappear postresolution. These diverse populations of mononuclear phagocytes were observed alongside lymph node expansion and increased numbers of peripheral blood and peritoneal memory and regulatory lymphocytes. Based on our data and supported by others,21-24 we conclude that in response to resolving, but not hyperinflammation, DCs residing in naïve tissues take up antigens and migrate to local lymph nodes (including peritoneal milky spots25) to initiate lymphocyte activation. The latter is amplified by postresolution CCR2-expressing monocytes; whether these effector monocytes26 exert their effects after migrating into the cavity and/or directly from the blood21 remains to be clarified. Concomitantly, as inflammation resolves resMφs and moMφs trigger FoxP3 expression within CD4 T cells while moDCs trigger their proliferation. The resMφs repopulate the cavity with a proportion migrating to the draining lymph nodes to bring about lymph node contraction in an iNOS-dependent manner from day 9 to day 13 onward. Finally, populations of moMφs remain in tissues months after the inflammation has resolved, dictating the magnitude of subsequent acute innate inflammatory stimulation (see hypothesis shown in supplemental Figure 7).

The importance of IL-10 and TGF-β in zymosan-generated Mφs, in terms of counterbalancing adaptive immune responses, was reported by others.27 The resMφs expressing TGF-β and IL-10 as a consequence of phagocytosing apoptotic PMNs28 migrate to the lymph node and spleen expressing immune-suppressive iNOS. These cells are likely to remain in lymphoid organs with a role in terminating adaptive immune responses and long–term, tempering of the severity of future antigen-specific immunity. A role for iNOS in this setting was illustrated in the context of “adjuvant immunogenicity,” first described more than 40 years ago, which was found to be dependent on the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within the adjuvant.29 Exposure to complete Freund’s adjuvant can impair the subsequent expression of autoimmune disease in rodents. This immunoprotective effect was demonstrated in multiple autoimmune disease models, both spontaneous and induced and in multiple species, including rats,30-33 mice,34 and guinea pigs.29,35 In each case, preimmunization with Freund’s complete adjuvant alone up to a month before the disease induction by immunization resulted in decreased incidence and severity of disease29-31,35,36 in an iNOS-dependent manner.37 Similarly, Mφ-mediated immunosuppression has been reported after bacteria, fungi, and parasite38 infection. For instance, mice immunized with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium (SL3235), although protected against virulent challenge, are unable to mount in vivo and in vitro antibody responses to non-Salmonella antigens, such as tetanus toxoid and sheep red blood cells, and exhibit profoundly suppressed responses to B- and T-cell mitogens. It transpires that suppression of antibody responses is mediated by iNOS within Mφs.39-42 Collectively, we argue that, in addition to bridging the gap between innate and adaptive immunity, resolution may also establish a phase of immunologic tolerance. It is unclear why a PMN-driven, acute onset phase of inflammation should be accompanied, paradoxically, by a prolonged phase of immune suppression. One possibility is to suppress the development of maladaptive immune response leading to autoimmunity.

In contrast, injecting high-dose zymosan (10 mg) resulted in a substantial inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising classically activated (M1)-like Mφs secreting high levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6 (>2000 pg/mL). Compared with resolving inflammation, such an inflammatory insult triggered substantially reduced numbers of Tregs and effector/memory lymphocytes. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as interferon (IFN) and TNF-α, interfere with antigen-specific T-cell responses43-45 and clearance of viral and mycobacterial infections in mice.46,47 Furthermore, inhibition of these cytokines enhances pathogen clearance and resolution of disease, an effect that is dependent on the presence of T cells. This suggests that excessive inflammation inhibits antigen-specific T-cell function and therefore immunity to pathogens.

Although the M1/M2 classification of macrophages was largely borne out of isolated monocytes incubated with defined growth factors in vitro, the phenotype of Mφ populations is likely to be more complex and overlapping, contingent on tissue, phase of inflammation, and the nature of the inciting inflammatory stimuli. We identified at least 4 distinct populations of monocyte/Mφs, each with a role in the resolution and in the development and control of adaptive immunity. In terms of individual cell phenotypes, we found that resMφs expressed TGF-β1 and IL-10, presumably as a consequence of phagocytising apoptotic PMNs; these cells also expressed ALOX-15 and TIMD4 to facilitate the recognition and uptake of apoptotic cells.12-14 In contrast, moMφs expressed IL12p35, whereas moDCs were enriched for IL1β, CCR7, CCR2, and CCL7. Taking this further, populations of moMφs that persisted in the cavity for months postinflammation were phenotypically different from resMφs. These data underline the fact that despite experiencing the same inflammatory cues, different monocyte/macrophage populations possess diverse phenotypes that are neither M1 nor M2, but are commensurate with the phase of inflammation. Indeed, this probably extends to macrophage populations occupying different tissue niches under physiological48,49 and disease conditions.

As reported by others using thioglycollate-induced peritonitis,17 we also found a population of moMφs that persisted in the peritoneum for at least 2 months postresolution. The phenotype of these cells was different to that of resMφs at this time; indeed the phenotype of day 60 moMφs was also different than the phenotype early in the inflammatory response (at 72 hours). Moreover, the phenotype of resMφs 60 days post-zymosan was different to the inflammatory characteristics in the naïve cavity. This emphasizes functional plasticity in macrophage phenotype congruent with the environment. Specifically, despite coexisting in the same inflammatory milieu, macrophages of different origins acquire distinct phenotypes that change throughout inflammation. This emphasizes that far from revering back to the state, the tissue experience before resolution, postresolution tissues experience a state of “adaptive homeostasis,” which dictates the magnitude of subsequent inflammatory stimuli. This is an area that requires further exploration in the future.

In summary, we show that resolution is not the end of the immune response to infection/injury but that it acts as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity, thereby adding a third phase to acute inflammation after acute and resolution, namely postresolution. Disruption of proresolution pathways by hyperinflammatory stimuli, for instance, impairs the development of specific immunity. These data redefine resolution as the creation of a tissue microenvironment that facilitates interaction between the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system and that postresolution tissue that acquires a state of “adapted homeostasis.”

Acknowledgments

D.W.G. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow. M.S. salary was supported by a studentship from the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom. J.N. was supported by D.W.G.’s fellowship.

This work was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council, United Kingdom (D.W.G.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.S. and J.N. performed the majority of experiments; E.K. designed primer sequences and carried out polymerase chain reaction; F.A.-V. and S.Q. performed tolerance experiments; S.Y. designed monocyte ablation studies and performed studies in which mice were exposed to a second inflammatory stimulation; M. Mack provided MC-21 and expertise on monocyte biology depletion; M. Motwani performed lymphocyte proliferation and phenotyping studies; T.A. performed; and D.W.G. designed experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Derek W. Gilroy, Division of Medicine, Centre for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University College London, 5 University St, London, United Kingdom WC1E 6JJ; e-mail: d.gilroy@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Serhan CN, Brain SD, Buckley CD, et al. Resolution of inflammation: state of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J. 2007;21(2):325–332. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7227rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(12):1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamieson T, Cook DN, Nibbs RJ, et al. The chemokine receptor D6 limits the inflammatory response in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(4):403–411. doi: 10.1038/ni1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohr J, Knoechel B, Abbas AK. Regulatory T cells in the periphery. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:149–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivedi SG, Newson J, Rajakariar R, et al. Essential role for hematopoietic prostaglandin D2 synthase in the control of delayed type hypersensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(13):5179–5184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507175103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bystrom J, Evans I, Newson J, et al. Resolution-phase macrophages possess a unique inflammatory phenotype that is controlled by cAMP. Blood. 2008;112(10):4117–4127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biermann H, Pietz B, Dreier R, Schmid KW, Sorg C, Sunderkötter C. Murine leukocytes with ring-shaped nuclei include granulocytes, monocytes, and their precursors. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65(2):217–231. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosn EE, Cassado AA, Govoni GR, et al. Two physically, functionally, and developmentally distinct peritoneal macrophage subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(6):2568–2573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, et al. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(11):4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boring L, Gosling J, Chensue SW, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(10):2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stables MJ, Shah S, Camon EB, et al. Transcriptomic analyses of murine resolution-phase macrophages. Blood. 2011;118(26):e192–e208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-345330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi N, Karisola P, Peña-Cruz V, et al. TIM-1 and TIM-4 glycoproteins bind phosphatidylserine and mediate uptake of apoptotic cells. Immunity. 2007;27(6):927–940. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Sullivan TP, Vallin KS, Shah ST, et al. Aromatic lipoxin A4 and lipoxin B4 analogues display potent biological activities. J Med Chem. 2007;50(24):5894–5902. doi: 10.1021/jm060270d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uderhardt S, Herrmann M, Oskolkova OV, et al. 12/15-lipoxygenase orchestrates the clearance of apoptotic cells and maintains immunologic tolerance. Immunity. 2012;36(5):834–846. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albina JE, Abate JA, Henry WL., Jr Nitric oxide production is required for murine resident peritoneal macrophages to suppress mitogen-stimulated T cell proliferation. Role of IFN-gamma in the induction of the nitric oxide-synthesizing pathway. J Immunol. 1991;147(1):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack M, Cihak J, Simonis C, et al. Expression and characterization of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5 in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166(7):4697–4704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336(6077):86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330(6005):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serra MF, Diaz BL, Barreto EO, et al. Mechanism underlying acute resident leukocyte disappearance induced by immunological and non-immunological stimuli in rats: evidence for a role for the coagulation system. Inflamm Res. 2000;49(12):708–713. doi: 10.1007/s000110050650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano H, Lin KL, Yanagita M, et al. Blood-derived inflammatory dendritic cells in lymph nodes stimulate acute T helper type 1 immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):394–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.León B, López-Bravo M, Ardavín C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity. 2007;26(4):519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471(7340):629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ersland K, Wüthrich M, Klein BS. Dynamic interplay among monocyte-derived, dermal, and resident lymph node dendritic cells during the generation of vaccine immunity to fungi. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(6):474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rangel-Moreno J, Moyron-Quiroz JE, Carragher DM, et al. Omental milky spots develop in the absence of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells and support B and T cell responses to peritoneal antigens. Immunity. 2009;30(5):731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mildner A, Yona S, Jung S. A close encounter of the third kind: monocyte-derived cells. Adv Immunol. 2013;120:69–103. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillon S, Agrawal S, Banerjee K, et al. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(4):916–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(4):890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kies MW, Alvord EC., Jr [Prevention of allergic encephalomyelitis by prior injection of adjuvants]. Nature. 1958;182(4642):1106. doi: 10.1038/1821106a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hempel K, Freitag A, Freitag B, Endres B, Mai B, Liebaldt G. Unresponsiveness to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in Lewis rats pretreated with complete Freund’s adjuvant. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1985;76(3):193–199. doi: 10.1159/000233691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens DB, Karpus WJ, Gould KE, Swanborg RH. Studies of V beta 8 T cell receptor peptide treatment in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;37(1-2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90163-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raziuddin S, Kibler RF, Morrison DC. Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in Lewis rats: inhibition by bacterial lipopolysaccharides and acquired resistance to reinduction by challenge with myelin basic protein. J Immunol. 1981;127(1):16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawano Y, Sasamoto Y, Kotake S, Thurau SR, Wiggert B, Gery I. Trials of vaccination against experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis with a T-cell receptor peptide. Curr Eye Res. 1991;10(8):789–795. doi: 10.3109/02713689109013873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cua DJ, Hinton DR, Kirkman L, Stohlman SA. Macrophages regulate induction of delayed-type hypersensitivity and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25(8):2318–2324. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisak RP, Zweiman B. Immune responses to myelin basic protein in mycobacterial-induced suppression of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Cell Immunol. 1974;14(2):242–254. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(74)90209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falk GA, Kies MW, Alvord EC., Jr Passive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: mechanisms of suppression. J Immunol. 1969;103(6):1248–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahn DA, Archer DC, Gold DP, Kelly CJ. Adjuvant immunotherapy is dependent on inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 2001;193(11):1261–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenstein TK. Suppressor macrophages. In: Zwilling BS, Eisenstein TK, editors. Macrophage-Pathogen Interaction. New York: Marcrl Dekker Inc; 1994. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacFarlane AS, Huang D, Schwacha MG, Meissler JJ, Jr, Gaughan JP, Eisenstein TK. Nitric oxide mediates immunosuppression induced by Listeria monocytogenes infection: quantitative studies. Microb Pathog. 1998;25(5):267–277. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang D, Schwacha MG, Eisenstein TK. Attenuated Salmonella vaccine-induced suppression of murine spleen cell responses to mitogen is mediated by macrophage nitric oxide: quantitative aspects. Infect Immun. 1996;64(9):3786–3792. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3786-3792.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenstein TK, Huang D, Meissler JJ, Jr, al-Ramadi B. Macrophage nitric oxide mediates immunosuppression in infectious inflammation. Immunobiology. 1994;191(4-5):493–502. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.al-Ramadi BK, Meissler JJ, Jr, Huang D, Eisenstein TK. Immunosuppression induced by nitric oxide and its inhibition by interleukin-4. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22(9):2249–2254. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.González-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(2):125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boasso A, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Shearer GM. HIV-induced type I interferon and tryptophan catabolism drive T cell dysfunction despite phenotypic activation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cope AP, Liblau RS, Yang XD, et al. Chronic tumor necrosis factor alters T cell responses by attenuating T cell receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 1997;185(9):1573–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, et al. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science. 2013;340(6129):202–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1235208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teijaro JR, Ng C, Lee AM, et al. Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science. 2013;340(6129):207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1235214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosas M, Davies LC, Giles PJ, et al. The transcription factor Gata6 links tissue macrophage phenotype and proliferative renewal. Science. 2014;344(6184):645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1251414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue-specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell. 2014;157(4):832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]