Abstract

Background

One in four Americans, and 70% of people who have dementia, will spend their final days in nursing home care. Clinical research, particularly clinical trials, rarely includes this population due to unique challenges in research methods and ethics. Families of advanced dementia patients make choices about tube feeding and other feeding options with limited access to information or communication. The cluster randomized trial, Improving Decision Making about Feeding Options for Dementia Patients, tests a decision aid intervention to improve the quality of decision making for this choice.

Purpose

Our objectives are 1) to describe the methods used in this trial; 2) to describe challenges and strategies for effective nursing home and nursing home resident recruitment and retention; and 3) to describe research ethics approaches to minimize harms and maximize benefits for this population.

Methods

The study is a cluster randomized trial of a decision aid to inform and support the choice between tube feeding and assisted oral feeding in advanced dementia. Study subjects are paired surrogate decision-makers and residents with advanced dementia and feeding problems, enrolled from nursing homes in North Carolina.

Results

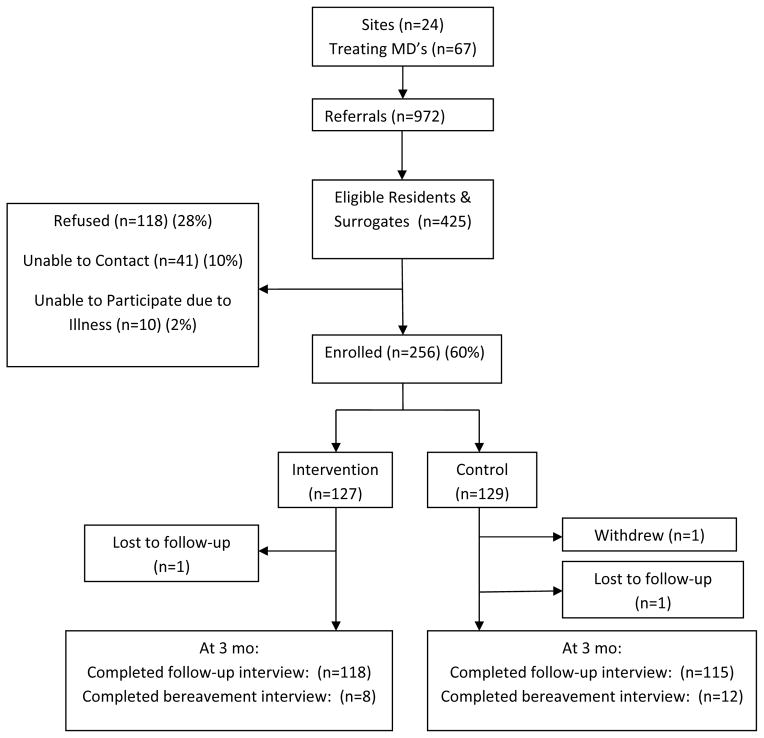

This trial enrolled 256 paired surrogate decision-makers and residents in 24 nursing home sites, and 99% completed participation through the 3-month study period. The research team had prior clinical and investigative experience in this setting, and used multiple strategies to recruit and retain nursing home sites, providers, surrogates and the residents for whom they spoke. Informed consent and human subjects protections were designed to address the vulnerability of this population.

Limitations

Cluster randomization was necessary to avoid contamination between control and intervention subjects, but may introduce confounding by site and intra-class correlation effects in analyses.

Conclusions

Strategies that facilitate nursing home recruitment, study subject recruitment and human subjects protections for a vulnerable population may be used by future investigators to expand the research evidence base for nursing home and dementia care.

Keywords: nursing home, dementia, nutrition, decision-making

Background

Nursing homes become the residence and primary health care setting for many older Americans. While only 5% of the population over age 65 lives in a nursing home at any one time, 44% of people who reach age 65 will spend some time in nursing home care. 1,2 Compared to older adults in the community, people who live in nursing homes are more likely to be women, Caucasian, and to have chronic illnesses that affect physical and cognitive functioning. Over 75% of nursing home residents need assistance for 4 or more activities of daily living. Cognitive impairment is common; nearly 50% of residents have dementia.3 Nursing home admission typically is triggered by cardiac, neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses, combined with care needs that exceed home and community services. 4 People who enter a nursing home will often remain there until death; one in four Americans, and 70% of people who have dementia, will spend their final days in this setting.5,6

Despite the compelling individual and public health impact of nursing home care, clinical research, particularly clinical trials, rarely includes this population. The institutional characteristics of nursing home care may present challenges that deter investigators, or result in incomplete studies.7,8,9,10 Among nearly 5000 original articles published in 6 leading medical journals in 2008, not one focused on nursing home care.11 Nursing home residents are medically frail and socially vulnerable, and many are unable to provide informed consent for research participation. Serious chronic illness may result in relatively high drop-out rates from longitudinal studies, with implications for both the initial sample size and analytic strategies to address missing data.12 Long-term care facilities serve concurrently as housing and as health care institutions, but are outside the training and practice experience of most physicians and nurses. A majority of physicians do not provide nursing home care, and those who do are rarely available on site.13 Annual turnover rates among nursing home aides range from 59% to over 100%; turnover rates for nurses and administrators are higher than in other healthcare settings.14,15 Nursing homes are more highly regulated than other health care settings, and administrative staff spend significant time responding to quality oversight requirements. These aspects of nursing home care make some providers wary of researchers’ motives or of the time demands of research participation.

Investigators who wish to conduct research in nursing homes and long-term care facilities will benefit from familiarity with these institutions and with recruitment strategies used in previously successful research studies. We describe the methods used to conduct a cluster randomized trial of a decision support intervention in 24 nursing home sites. Our objectives are 1) to describe the methods used in this randomized trial for effective nursing home and nursing home resident recruitment and retention; and 2) to describe research ethics approaches to minimize harms and maximize benefits for this population.

Rationale and Design of the Clinical Trial

Patients with advanced dementia have high rates of feeding problems such as weight loss, dysphagia and dehydration. The presence of these problems raises the choice of continued oral feeding or placement of a feeding tube. The current quality of decision-making about feeding tubes and assisted feeding options is poor.16,17 One-third of nursing home residents with dementia and feeding problems have a feeding tube placed despite limited evidence of medical benefits.18

The Improving Decision-Making about Feeding Options for Dementia Patients (IDM) study is a cluster randomized trial funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research. The primary research objective is to test whether an evidence-based decision aid for surrogate decision-makers could improve the quality of informed decision-making. Residents with advanced dementia and their surrogates were followed for 3 months to examine the effects of the decision aid on surrogate knowledge and decisional conflict, the quality of decision-making, and treatments used. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of North Carolina School Of Medicine, and for individual research sites by the Institutional Review Boards of Alamance Regional Hospital and the East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine. A Data Safety Monitoring Committee reviewed data reports every 6 months throughout the study period.

Nursing Home Sites and Randomization

The research was conducted in 24 North Carolina nursing homes, recruited and randomized in pairs matched for business model, size, and percent minority residents. Participating sites have characteristics that make them representative of nursing homes in the state and nation (Table 1). The unit of randomization was the nursing home to minimize contamination between intervention and control groups. The cluster randomization procedure reduces risk of contamination and mimics expected adoption of decision aids in practice, which is likely to occur at the level of an organization or medical practice. No contamination occurred during the study period, as evidenced by complete absence of decision aid materials in control nursing home sites. Initially designed for 12 nursing homes, the study was expanded to a larger number of nursing homes due to the smaller than expected recruitment from each site. This modification also reduced cluster effects in analysis.

Table 1.

Nursing Home Characteristics

| Characteristics | Study Nursing Homes (n=24) | NC Nursing Homes (n=423) | US Nursing Homes (n=15,691) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Beds | |||

| Mean (range) | 129.7 (60–252) | 102.5 | 106.3 |

| Medicare Beds | |||

| Mean (range) | 108.6 (0–232) | 96.2 | 91.3 |

| Ownership | |||

| For Profit % | 67% | 73.5% | 67.0% |

| Not for profit % | 33% | 22.9% | 26.6% |

| Alzheimer Unit % | |||

| Mean | 29% | 16.6% | |

| NP/PA on staff % | 66% | 49.3% | |

| Full time | 50% | ||

| Part time | 50% | ||

| % African American Residents | |||

| Mean (range) | 29.7% (0–80%) | 24.9% | 13.6% |

| % of Residents Tube Fed | |||

| Mean (range) | 4.6% (0–7%) | 6.92% | 5.97% |

| DNR % | |||

| Mean (range) | 64.3% (27–85%) | 54% | 51.5% |

| Feeding Aides % | 63% | ||

| Assisted Dining % | 83% | ||

| Survey Deficiencies | |||

| Mean (range) | 6 (0–30) | 5 | 8 |

| Star Rating | |||

| Mean (range) | 2.5 (1–5) | 2.9 | |

| Staffing-hrs per resident per day | |||

| Licensed Staff | |||

| Mean (range) | 1.5 (1.0–2.9) | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| CNAs | |||

| Mean (range) | 2.5 (1.9–4.4) | 2.3 | 2.4 |

Sources: OSCAR, CMS, Brown 2007

NC=North Carolina; US=United States; NP/PA=Nurse practitioner/Physician assistant; DNR=Do Not Resuscitate; CNA=Certified nursing assistant

Research Participants

Research participants were dyads of residents of the nursing home who had advanced dementia and feeding problems and their surrogate decision-makers. Trained research assistants conducted all eligibility screening and preliminary chart reviews under an IRB-approved Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) waiver. Four research assistants with clinical social work or non-clinical background completed all enrollment and data collection from chart reviews and interviews. All direct health care providers and research subjects were blinded to group assignment. Due to cluster randomization, data collectors were not blinded to group assignment. Adapting methods used in a large prospective study of advanced dementia,19 they first identified individuals who scored 5–6 on the most recent Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) in the Minimum Dataset (MDS), a federally required data instrument completed on admission, quarterly, and whenever a change in clinical status occurred. The CPS is a reliable and valid measure of cognitive status in nursing home populations.20 It uses 5 MDS variables to rate cognitive performance, from 0=intact to 6=very severe impairment. Eligible residents had a chart diagnosis of dementia with severity staged 6–7 on the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS), and had chart evidence of a feeding problem.21 Feeding problems were defined as poor intake, dysphagia or weight loss. Poor intake was defined as leaving ≥ 25% of most meals uneaten over the past 14 days based on dietary and MDS records. Dysphagia was defined as difficulty with swallowing, choking on food or liquid, dehydration, dysphagia diet, or aspiration occurring during the past 6 months based on physician, nursing, dietary and MDS review. Weight loss was defined as > 5% of total body weight lost in the past 30 days or >10% of total body weight lost over 6 months. To be included, residents had to be aged 65 or older and had to have a surrogate decision-maker to provide informed consent for both the resident and the decision-maker’s participation. Residents were excluded who had a feeding tube, had a “Do Not Tube Feed” order, or were enrolled in hospice care. Other exclusion criteria were obesity (BMI > 26 kg/m2) or weight loss attributed to diuresis.

Surrogate decision-makers for eligible residents were mailed an invitation to participate; they provided written informed consent for their participation and for the resident with dementia. Eligible surrogates were guardians or Health Care Powers of Attorney, when available or primary family contacts who agreed they were the person most likely to be involved in clinical decision-making. Unrelated court-appointed guardians were excluded. Surrogates who declined to participate were more likely to live outside North Carolina (p<0.001, chi-square comparison of in vs. out of state residence) or to be spouses or friends (p=0.002, chi-square comparison across relationship categories) than were surrogates who agreed to participate (Table 2). No race or ethnicity data were available for non-participating surrogates, but refusal rates did not differ between nursing home sites with high versus low percentages of minority residents.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participating and Non-participating Surrogate Decision-Makers

| Characteristics | Participants N=256 | Non-participants N=169 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 166 (65%) | 103 (61%) |

| Male | 90 (35%) | 66 (39%) |

| Not resident of North Carolina | 14 (5%) | 15 (9%) |

| Relationship to Nursing Home Resident | ||

| Spouse | 21 (8%) | 22 (13%) |

| Daughter | 118 (46%) | 61 (36%) |

| Son | 61 (24%) | 48 (28%) |

| Grandchild | 11 (4%) | 4 (2%) |

| Nephew or Niece | 20 (8%) | 10 (6%) |

| Sibling | 13 (5%) | 8 (5%) |

| Other family | 9 (4%) | 2 (1%) |

| Friend | 3 (1%) | 14 (8%) |

Development and Literacy Testing of the Decision Aid

The decision aid was developed from a previously pilot tested decision aid, and provided in both a print booklet and audio-recorded format. 22 Decision aids are print, audio or video materials that provide structured, evidence-based information in support of an important clinical choice. Content includes information about the underlying health condition, treatment options, the risks and benefits of each option, and guidance for how to choose between options. Content was updated with review of relevant medical literature, and structured to conform to the International Patient Decision Aid Standards statement.23 Text was revised to a 6th grade reading level using the Fog Index method developed by the Education, Language and Developmental Training Programmes organization.24 With the assistance of health literacy experts, the decision aid was reviewed using the Suitability Assessment of Materials procedure, a validated method to modify health education materials for a lower health literacy audience. The decision aid was tested in 2 cycles of cognitive interviews with 6 Caucasian and 6 African-American family caregivers.25 Interview questions explored information transmission about dementia and feeding problems, and pros and cons of feeding options. Participants in that test group were asked to critique clarity, balance, and cultural sensitivity of the decision aid; their suggestions for improvements were incorporated in the final version.

Intervention and Control Arms

Surrogates from nursing homes assigned randomly to the intervention reviewed the decision aid on feeding options for dementia patients in the format of their choice (print or audio) during a baseline interview. Research assistants were present, but trained not to provide commentary or additional information beyond what was contained in the decision aid. Decision aid content included information about dementia, feeding problems in dementia, advantages and disadvantages of feeding tubes or assisted oral feeding options, including feeding for comfort, and the role of the surrogate in decisions. Each surrogate in the intervention arm received a copy of the decision aid in audio or print format for review at home; they were encouraged to use the decision aid in future discussions with nursing home staff or with treating physicians. Control surrogates received usual care, consisting of any information on this decision provided by nursing home staff or the nursing home physician in the course of usual clinical care, or other information resources sought by the surrogate. All other aspects of study design and data collection procedures were identical for intervention and control participants.

Data Collection

Surrogate decision-makers participated in an in-person interview at baseline and follow-up telephone interviews at 1 and 3 months. Additional data were collected from the resident’s nursing home chart at baseline, 1, 3, 6 and 9 months. Mortality data were confirmed using state-level death certificate review. Surrogate baseline interviews provided data on knowledge of feeding options and decisional conflict. Follow-up interviews with surrogates provided data on decisional conflict, frequency of discussions of treatment choices, and satisfaction and regret related to decisions about feeding options. Decisional conflict was measured using the Decisional Conflict Scale, developed and validated by O’Connor. This scale consists of 16 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale; this measure has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.78–0.92), an overall test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.81.26 The Decisional Conflict Scale includes 3 subscales; a) uncertainty, b) effective decision-making, c) factors contributing to uncertainty. Frequency of discussion was measured using interview report of discussions about feeding options with treating physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants or nursing home staff. Decisional regret and satisfaction, secondary outcomes, were measured using reliable and valid instruments. 27,28 Chart reviews provided data on the resident’s health and nutritional status, and frequency of treatment decisions including new use of feeding tubes, new orders not to use feeding tubes, and new assisted feeding interventions.

Research Challenges and Strategies

Strategies for Recruiting and Retaining Nursing Home Sites

Our approach to recruiting and retaining nursing homes, and the providers working there, was based on gaining entrée through prior contacts, on a respectful approach, and on use of methods that do not burden clinical staff. (Table 3) We approached 29 and successfully recruited 24 sites; all recruited sites participated through the entire study period. Recruitment was facilitated by researchers’ prior experience and familiarity with nursing home providers. When research participants are nursing home residents, the research design and budget must include time and personnel for initial nursing home recruitment prior to recruitment of individuals. Nursing home staff have limited experience with research and work demands that are time intensive and unpredictable. They face intensive external scrutiny and may have concerns that research is designed to expose deficiencies rather than to improve care of residents.

Table 3.

Nursing Home Research Challenges and Strategies

| Challenge | Research Strategies | Implications for Design |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Recruiting nursing homes and providers | Gaining entrée through prior experience, contacts or a research consortium | 1. Investigators with experience and evidence of support from nursing home providers |

| Respect, reciprocity and flexibility in approach to providers | 2. Adequate funded time to recruit sites and providers before recruiting subjects | |

| 3. Site study liaisons | ||

| 4. Effective and responsive communication | ||

| 5. Methods to share findings or offer reciprocal benefits such as training for providers | ||

| 6. Anticipate interruptions and need to re-schedule meetings | ||

| Methods do not burden or distract clinical staff from care | 7. Research roles separated from clinical roles | |

|

| ||

| Recruiting and retaining residents and family surrogates as research participants | Reciprocity, flexibility and persistence in approach to residents and family caregivers | 8. Design includes clear potential benefits for residents |

| 9. Adequate funded time to recruit residents and families | ||

| 10. Compensation for time to participate | ||

| Methods minimally burden seriously ill residents and stressed family caregivers | 11. Data collection methods minimize demands on study participants | |

| Sample size calculations address drop-out due to illness and death | 12. Design and analysis plan address attrition during follow-up | |

|

| ||

| Research ethics for a vulnerable population | Participant and societal benefits clearly outweigh burdens | 13. Prioritize designs with significant potential benefits |

| IRB review clearly specified for all sites | 14. Anticipate time to assure multiple IRB reviews | |

| 15. Limited HIPAA waiver for eligibility screening | ||

| 16. Consent documents copied and on site for review | ||

To demonstrate respect and to address these possible concerns, the Principal Investigator or another investigator with experience gained entrée with nursing home administrators, and invited staff leaders to an informational meeting to discuss any questions or concerns with members of the investigative team. We sought to respect the demanding nature of nursing home work in study methods. Research design structured adequate funded time for recruiting providers. Investigators sought commitment from all key leaders, including the administrator, director of nursing, medical director, social worker, nutritionist, speech therapist, and other treating physicians. Since physicians were rarely on site at the nursing homes, physician investigators contacted 67 treating physicians from the 24 sites to provide study orientation information and seek permission to include each physician’s patients in the study. Physician contact was time-consuming; repeated telephone calls, mailings, and an informational website were required to share information about the study with physicians.

Subsequent communication occurred through a study liaison at each site. Study liaisons were not paid and did not conduct study procedures. Researchers kept communication effective by making calls frequent but brief, demonstrating respect for the time demands of the liaison’s clinical responsibilities. Whenever leadership changes occurred during the study period, additional informational meetings were offered. We shared findings in training as a way to benefit staff. At the conclusion of data collection, we provided an in-service educational session on feeding options in dementia at every site and provided copies of the decision aid for clinical use. Although research methods were highly specified, research assistants were trained to be both persistent and flexible, and to respect the needs of staff. For example, we honored requests to limit time on site to specific days, or to provide timely lists of surrogate decision-makers who had been contacted. Whenever state surveyors visited a site or an unexpected family meeting occurred, research assistants re-scheduled data collection for a more convenient time. Finally, we structured our approach to avoid burdening or distracting clinical providers. No staff time or effort was requested for research activities; all participant contact and data collection were the responsibility of research team members.

Strategies for Recruitment and Retention of Residents and Family Surrogates

Our recruitment strategy for potential nursing home sites was based on principles of respect, reciprocity and flexibility.29 The initial research design was considered in terms of potential benefit to residents. Recruitment approaches ensured adequate time to address concerns of family surrogates, and provided compensation for their time commitment to the study interviews.

In addition to modest monetary compensation for their time, surrogate participation was facilitated by persistence and flexible scheduling. Sixty percent, 256 of those eligible, consented to participate; follow-up data collection at 3 months was completed for 99%. Nursing home sites varied widely in the number and percent of recruited research participants, with enrollment ranging from 3–36 per site (30–94% of eligible referrals). Research assistants called up to 12 times to schedule interviews and provided additional information about the study whenever requested. They offered interviews at the time and location most convenient for the surrogate decision-maker, including baseline interviews by telephone for out of state consenting surrogates. Whenever the surrogate desired the support of another family member during the interview, the request was granted if it reflected the manner in which important health care decisions were made. To facilitate identification of potentially eligible participants, we used an approach that screened many potential family surrogates before contacting potentially eligible individuals. Many nursing homes were able to generate a computerized list of selected MDS variables. For nursing homes unable to generate a computerized data, research assistants provided broad eligibility criteria to the study liaison in each site who returned a list of charts for review. Liaisons were encouraged to talk with other interdisciplinary team members to ensure potentially eligible residents were identified. After eligibility chart reviews, research assistants provided feedback to the liaison to improve their understanding of eligibility, and re-contacted them once a quarter to seek additional candidates.

Finally, sample size calculations address the challenges of screening this population and recruiting adequate numbers, in anticipation of events such as illness and death that may cause surrogates to refuse or drop out. Eligibility screening used broad initial criteria to maximize identification of potential participants. Screening criteria were communicated in simple language to minimize difficulty for the liaison while assuring protection of confidential healthcare information. Recruitment and retention was a time-intensive task for this vulnerable population with ongoing changes in health status and their stressed family caregivers.. A total of 972 resident records were screened to identify 425 eligible resident-surrogate decision-maker dyads. (Figure)

Figure.

Improving Decision-Making Study Recruitment and Retention

Research Ethics for a Vulnerable Population

Research ethics approaches for informed consent, confidentiality, and distribution of benefits and burdens of research in nursing homes should recognize that residents are a vulnerable population. Nursing home residents are vulnerable because of their serious level of illness, their cognitive impairment and loss of decision-making capacity, and their dependence on nursing home caregivers. The study was designed in an effort to maximize benefits and minimize potential harms. The decision aid intervention tested a means to enhance informed decision-making and, therefore, offered potential for direct benefit to residents and surrogates. Surrogates may have experienced some satisfaction from sharing their opinions, and contributing to the knowledge base for dementia care. Research procedures also were designed to minimize any distractions or demands on nursing home staff to ensure their continued focus on resident care. Data on outcomes was reviewed every 6 months by a Data Safety Monitoring Committee to ensure objective review for adverse effects of the intervention.

To meet the ethical challenges involved in research with a vulnerable population, study design anticipated multi-site and repeated human subjects committee reviews. The 24 nursing facilities were covered by several IRBs. Most of the nursing facilities were served by a single IRB committee as allowed by federal wide assurance. Federal wide assurance agreements are designed so that facilities lacking an IRB will operate in accord with guidelines established for the protection of human subjects in research and under the review of the IRB at the institution initiating the project.29 Two other IRBs also separately reviewed the study and approved it for the participating nursing homes for which they were responsible. Several sites also required review by an internal ethics committee or by corporate legal counsel. These various levels of review delayed the initiation of the study in individual sites, typically by 1 to 2 months. Because of the complexity of the review process, physician investigators were assigned to communicate with IRBs and site clinical leadership to ensure all questions and concerns from ethics reviews were addressed in a timely fashion. Frequent and detailed updates amongst the study team members regarding the issues raised by the individual IRBs helped to avoid additional delays in the approval process.

Candidates for this clinical trial were nursing home residents with advanced dementia and their surrogate decision-makers. Surrogates provided written consent for their own participation and for access to the resident’s confidential health information. Screening for study eligibility required that research assistants gain temporary access to medical records under a limited waiver of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Confidentiality was protected by de-identifying and securing abstracted records and by prompt destruction of medical chart data for non-participants. When a resident-surrogate dyad enrolled in the study, copies of the consent form and the HIPAA agreement form were kept on site at the nursing home.

Nursing homes experience external oversight of resident care; assessment and treatment of weight loss is a target condition. Administrators frequently questioned whether participation in this study would cause increased scrutiny from state surveyors. Study procedures were designed to abstract existing data from charts and to add no new information or practice modifications other than the approved decision aid. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services provide a brief federal guideline for research in nursing facilities which states that patients in nursing homes have the right to refuse participation in research.30 In North Carolina, no state guidelines exist regarding nursing home research. However, the state ombudsman contacted by the research team confirmed that the surveyors seek evidence of informed consent in patients’ charts, and consent documents were copied and provided to each nursing home site for potential surveyor review.

Conclusions

Clinical trials and other types of research rarely include nursing home residents, but research evidence is needed to guide clinical care of a large and expanding population. The Improving Decision Making research team had prior clinical and investigative experience in this setting, and used multiple strategies to recruit and retain nursing home sites, providers, families and the residents for whom they spoke. We successfully enrolled 256 paired surrogate decision-makers and residents in 24 nursing home sites, of whom 99% completed participation through the 3-month study period. Similar strategies may be useful to future investigators who aim to expand the research base for nursing home care.

Acknowledgments

Anne Jackman, MSW and Kathryn Wessell for assistance in the conduct of this research study, and Jan Busby-Whitehead, MD and Joanne Garrett, PhD for service on the Data Safety Monitoring Committee.

Funding source: NIH-National Institute for Nursing Research RO1 NR009826; ClinicalTrials.gov registration: University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, NCT01113749.

References

- 1.Spillman BC, Lubitz J. New estimates of lifetime nursing home use: have patterns of use changed? Med Care. 2002;40:965. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200210000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kemper P, Murtaugh CM. Lifetime use of nursing home care. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:595–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102283240905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magaziner J, German P, Zimmerman S, et al. The prevalence of dementia in a statewide sample of new nursing home admissions aged 65 and older: diagnosis by an expert panel. Gerontologist. 2000;40:663–672. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan GW. National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 Overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2009;13(167) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, et al. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno JM. [Accessed Nov 2, 2009];Facts on Dying. www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/factsondying.htm.

- 7.Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF. Research in nursing homes: practical aspects. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:182–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK. Striving to recruit: the difficulties of conducting clinical research on elderly care home residents. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2007;100:258–261. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.6.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder M, Tseng Y, Brandt C, et al. Challenges of implementing intervention research in persons with dementia: example of a glider swing intervention. Am J Alz Dis Other Dem. 2001;16:51–56. doi: 10.1177/153331750101600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baskin SA, Morris J, Ahronheim JC, Meier DE, Morrison RS. Barriers to obtaining consent in dementia research: implications for surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:287–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison RS. Suffering in silence: addressing the needs of nursing home residents. J Pall Med. 2009;12:671–672. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.9584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy SE, Allore H, Studenski SA. Missing data: a special challenge in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:722–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy C, Epstein A, Landry LA, et al. Physicians Practices in Nursing Homes: Final Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2006/phypracfr.htm. Viewed 12/04/09. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Care. 2005;43:616–626. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163661.67170.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donoghue C, Castle N. Leadership styles of nursing home administrators and their association with staff turnover. Gerontologist. 2009;49:166–174. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Golin C, et al. Surrogates’ perceptions about feeding tube placement decisions. Patient Ed and Couns. 2006;61:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson LC, Garrett J, Lewis C, et al. Physicians’ expectations of benefit from tube feeding. J Pall Med. 2008;11:1130–1134. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, Kabumoto G, Mor V. Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290:73–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, De Leon MJ, et al. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psych. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell SL, Tetroe J, O’Connor AM. A decision aid for long-term tube-feeding in cognitively impaired older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:313–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. for the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. viewed 2/10/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edit Central. http://www.editcentral.com/gwt1/EditCentral.html. Viewed 6/24/10.

- 25.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company; 1996. pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decisional regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:281–292. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, et al. Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: The Satisfaction with Decision Scale. Med Decis Making. 1996;16:58–64. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2340–2348. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS manual system. 2004 Nov 19; §483.10(b)(4) http://www.cms.hhs.gov/transmittals/downloads/R5SOM.pdf. Viewed 11/1/2009.