Abstract

Background

Clinicians are faced with using the current best evidence to make treatment decisions, yet synthesis of knowledge translation (KT) strategies that influence professional practice behaviors in rehabilitation disciplines remains largely unknown.

Purpose

The purposes of this study were: (1) to examine the state of science for KT strategies used in the rehabilitation professions (physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-language pathology), (2) to identify the methodological approaches utilized in studies exploring KT strategies, and (3) to report the extent that KT interventions are described.

Data Sources

Eight electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, ERIC, PASCAL, EMBASE, IPA, Scopus, and CENTRAL) were searched from January 1985 to May 2013 using language (English) restriction.

Study Selection

Eligibility criteria specified articles evaluating interventions or strategies with a primary purpose of translating research or enhancing research uptake into clinical practice.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts, reviewed full-text articles, performed data extraction, and performed quality assessment. The published descriptions of the KT interventions were compared with the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research's (WIDER) Recommendations to Improve the Reporting of the Content of Behaviour Change Interventions.

Data Synthesis

Of a total of 2,793 articles located and titles and abstracts screened, 26 studies were included in the systematic review. Eighteen articles reported interventions that used a multicomponent KT strategy. Education-related components were the predominant KT intervention regardless of whether it was a single or multicomponent intervention. Few studies used reminders or audit and feedback intervention (n=3). Only one study's primary outcome measure was an economic evaluation. No clear delineation of the effect on KT strategies was seen.

Limitations

Diverse studies were included; however, the heterogeneity of the studies was not conducive to pooling the data.

Conclusions

The modest-to-low methodological quality assessed in the studies underscores the gaps in KT strategies used in rehabilitation and highlights the need for rigorously designed studies that are well reported.

Clinicians are faced with using the current best evidence to make decisions for individual clients and to demonstrate their treatments improve clinical outcomes.1 Knowledge translation (KT) is an active process that facilitates the introduction of new evidence into practice and may identify optimum strategies to close the gap between research and clinical practice. More recently, many rehabilitation agencies and associations have promoted KT, which ultimately will benefit rehabilitation practitioners and consumers.2–4 A complex system of interaction and engagement processes exists to influence clinical behavior and outcomes, which is a broader process than evidence-based practice. The dynamics of knowledge flow are dependent on many factors, including the nature of the research and the targeted level (ie, clinical or organizational). This complexity differentiates itself from diffusion or dissemination of information.

Although the evaluation of KT strategies has primarily focused on nursing and medicine,5–7 the need for KT strategies in rehabilitation is recognized.8,9 Rehabilitation, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language pathology, has differing gaps in evidence and practice9–11 and implies that different KT approaches are needed.12 This diversity also is reflected in differing perceived barriers to implementing evidence-based initiatives.11

Knowledge translation is a competency for rehabilitation practice, yet few theory-driven KT strategies exist for rehabilitation.13 Research has called for comparison between pragmatic and theory-driven approaches to better define the impact of KT strategies.13 The comparison of KT interventions across disciplines may be a concern because of the lack of theory-informed interventions and differing natures and scopes of practice.

In general, a variety of KT strategies exist to embed evidence-based knowledge into practice. These strategies range from passive methods such as educational material to more active strategies such as audit and feedback and local opinion leaders.14 Traditional approaches such as published literature are regarded as reasonably ineffective KT strategies.5,15 This finding was substantiated by therapists working in the health care, community, and education systems who identified comprehension of published literature as a barrier to implementing research findings into practice.11 Knowledge translation strategies can be single or multicomponent interventions. Multicomponent interventions directed at specific barriers to implementation appear to be effective in changing professional behavior.16 Changing clinical behavior (in this case, using research) is dependent on not only individual factors but also factors at the macro (policy, funding) and meso (organization) levels.17,18

Despite the expressed need for KT strategies to be adopted in rehabilitation practice, the synthesis of KT activities within rehabilitation has not been fully explored. Menon and colleagues8 examined KT strategies to improve knowledge and attitudes of evidence-based practice and evidence-based practice behaviors in physical therapy and occupational therapy. Findings from their systematic review acknowledged that limited KT evidence existed; however, active, multifaceted approaches were suggestive of changing practice behaviors for physical therapists. Our earlier systematic review of KT activities for allied health professions, which included rehabilitation, dietetics, and pharmacy, showed that predominantly education-only approaches were used.9 The majority of articles retrieved, however, involved KT strategies for pharmacy. Because of more recent recognition of KT strategies used in rehabilitation, we performed an updated systematic review of published research of KT strategies that influenced professional practice behaviors in 3 rehabilitation disciplines: occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech-language pathology. More specifically, we identified, assessed, and evaluated the effects of KT interventions on physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language pathology. Additionally, we examined the state of science for KT strategies used in the rehabilitation professions, identified the methodological approaches utilized in studies exploring KT strategies, and reported the extent that KT interventions were described.

Method

This review builds upon an earlier systematic review of the KT interventions used in the allied health professions, including dietetics, occupational therapy, pharmacy, physical therapy, and speech-language pathology. Both the current and previous reviews used a modified systematic review protocol to synthesize diverse forms of research evidence.19 The study procedures we applied are documented in 2 previous publications: an allied health study protocol20 and an allied heath systematic review.9 For this review, we focused on 3 rehabilitation professions given the unique approach and clinical competencies required in each of these areas of rehabilitation practice.

Data Sources and Searches

Search strategies were developed and implemented by a health research librarian for 8 electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, ERIC, PASCAL, EMBASE, IPA, Scopus, and CENTRAL) using language (English) and date restrictions (January 1985–May 2013) (eAppendix). The decision to restrict the search to studies published in English was based on findings from systematic research evidence that reported no empirical evidence of bias seen if papers written in languages other than English were excluded.21 These date restrictions were purposively selected to capture all relevant KT literature because it was understood that the emergence of evidence-based medicine/evidence-based practice and the KT movements occurred during this time frame. All duplicate citations were identified and removed.

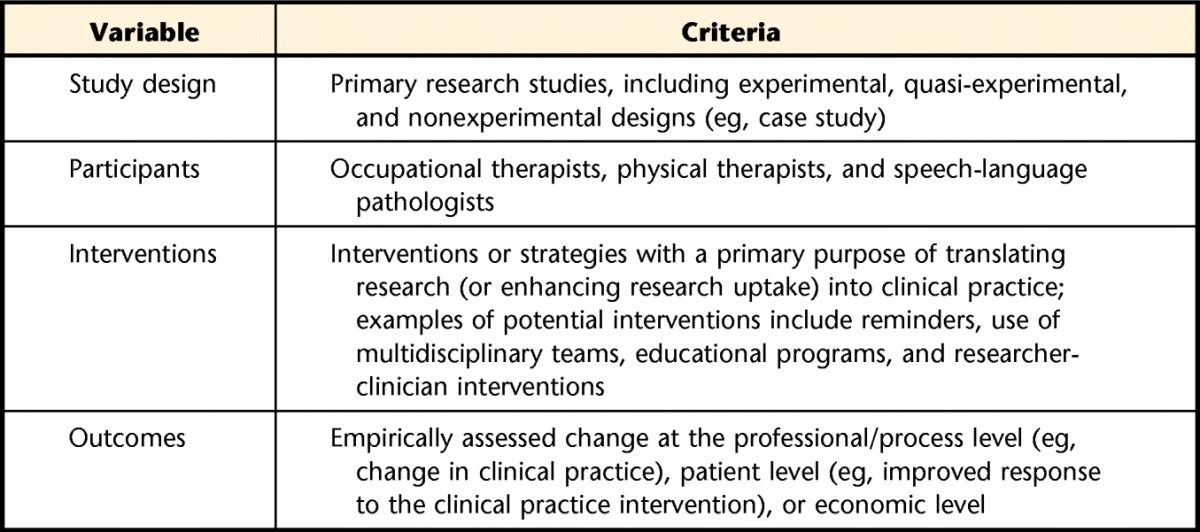

Studies were included in the review if they met the criteria outlined in Table 1. Specifically, the systematic review looked at interventional strategies with the primary purpose of translating research (or enhancing research uptake) into clinical practice of physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language pathology. The accepted outcomes of the KT interventions assessed change either quantitatively or qualitatively at the professional or process level, patient level, or economic level. Studies were not excluded based on research design. Only primary research studies were included.

Table 1.

Inclusion Criteria

Study Selection

Two reviewers (S.L.P., S.C.R.) independently screened the article titles and abstracts of the publications identified by the search strategy using broad criteria. If either reviewer selected a citation, the full-text article was obtained for further scrutiny. All rehabilitation studies retrieved from the earlier systematic review9 were re-screened. The potentially relevant full-text articles were further screened for selection using a standard study selection form based on the predetermined inclusion criteria. The study selection form was initially piloted on a sample of papers to ensure that the selection criteria were applied consistently between reviewers. Disagreements in study selection were resolved by discussion between the 2 reviewers or through third-party adjudication if the reviewers did not arrive at consensus. Full-text papers were included only if consensus was achieved by the reviewers.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer. Study data were extracted using a data extraction form based on the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) Data Collection Checklist.14 This classification scheme is currently used by the Cochrane Collaboration and widely used by other researchers. The research design of each study was determined using an algorithm.22 The user-friendly format of this algorithm helped identify a variety of research designs and standardized responses across reviewers. Other than to identify research design, the EPOC Data Collection Checklist was used as published.

Intervention Reporting

Descriptions of the KT interventions used in the selected articles were evaluated using the recommendations reported by the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) Recommendations to Improve Reporting of the Content of Behaviour Change Interventions.23 These recommendations emerged from the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) agreement.24 Developed in 2008, the WIDER recommendations comprise 4 categories: (1) detailed description of interventions in published papers, (2) clarification of assumed change process and design principles, (3) access to intervention manuals and protocols, and (4) detailed description of active control conditions. To meet the criteria outlined by WIDER, the description of the behavior intervention must contain all of the components described in each recommendation. The descriptions of the KT interventions were compared with the WIDER recommendations by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of quantitative studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. This tool assesses study quality by exploring selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis.25 An overall methodological rating was generated based on ratings of strong, moderate, or weak for each of the 8 sections. Content and construct validity and interrater reliability of this measure are considered good.26

The Quality Assessment Tool for Qualitative Studies was used to assess the methodological quality of qualitative studies.27 This tool consists of 5 detailed questions related to: (1) aims of the research; (2) research methods and design; (3) sampling; (4) data collection and analysis; and (5) results, discussion, and conclusions. An overall score ranging from 1 to 5 is generated, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of methodological rigor. Moderate interrater agreement (kappa=.53) has been reported with the use of this tool.27

Two reviewers assessed the methodological quality of the included studies independently. When disagreement occurred, discussion or third-party adjudication was used to achieve consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

All selected studies were included in the data synthesis regardless of methodological quality. To analyze and synthesize study data, we first stratified and analyzed articles for each of the 3 professions and then grouped them by study design. Data were subsequently analyzed according to the type of KT intervention strategy for each health care profession. A descriptive (narrative) analysis of the included studies was completed and potential patterns identified in terms of targeted behaviors, study outcomes, and intervention effectiveness. In accordance with EPOC guidelines, the main outcomes were defined as those outcomes that were deemed most important to the people who would be affected and that were considered valuable to people making decisions. Main outcomes were captured in the protocol. Other outcomes were defined as secondary outcomes that would be of interest to some readers but were not the most important outcomes for those who will be affected or those involved in decision making.28 Outcomes were classified as whether the change was statistically significant or not. If all of the changes seen with the main outcomes of a study were either statistically significant or not significant, they were classified as “consistent,” but if some of the changes seen with the main outcomes were significant and others were not significant, they were classified as “mixed.” Studies in which the results were not clearly linked to the identified outcomes were classified as “unclear.” Studies were classified as “not done” where no comparative statistics were provided or results were not reported for the identified outcomes.

This systematic review allowed us to: (1) identify successful strategies across professions and (2) describe the type of strategy, the targeted audience, and the circumstances under which it occurred.29 Lastly, we synthesized the evidence across the 3 rehabilitation disciplines to reflect the interprofessional nature and delivery of rehabilitation services. Because of the methodological and clinical heterogeneity of the included studies, meta-analyses could not be conducted.

Results

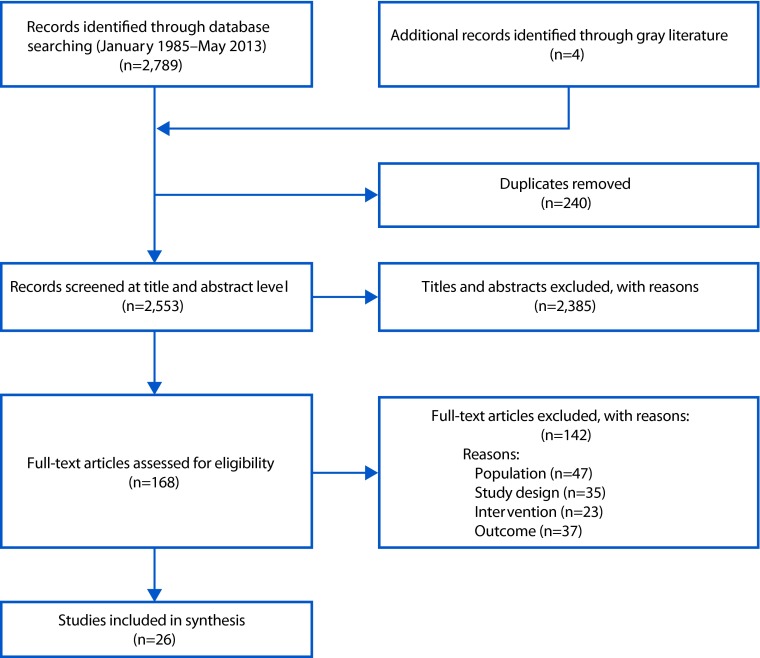

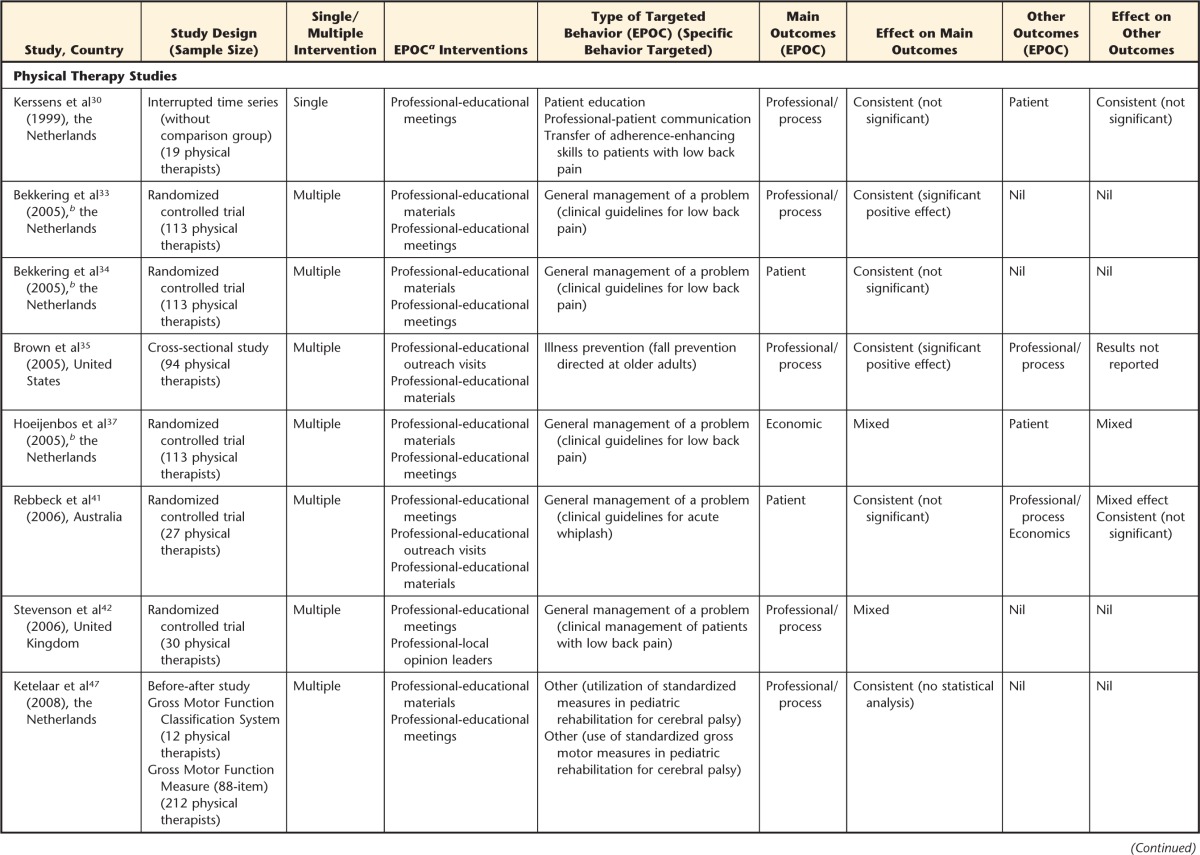

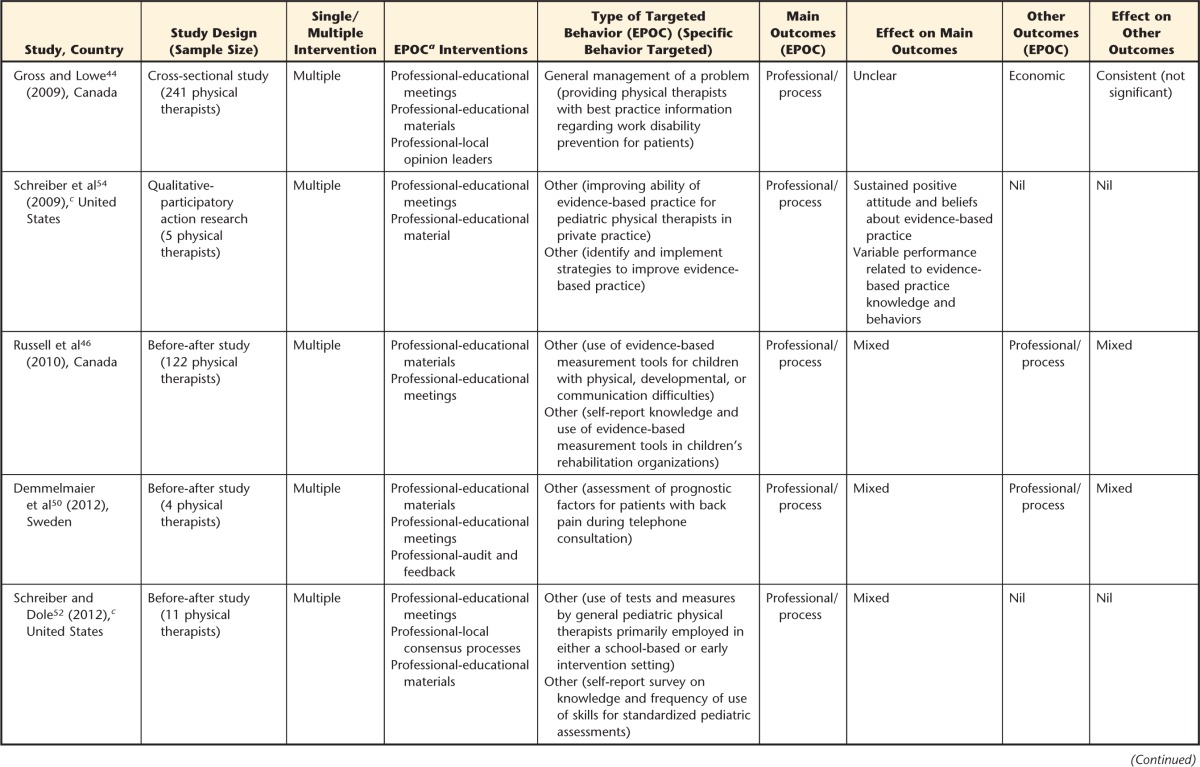

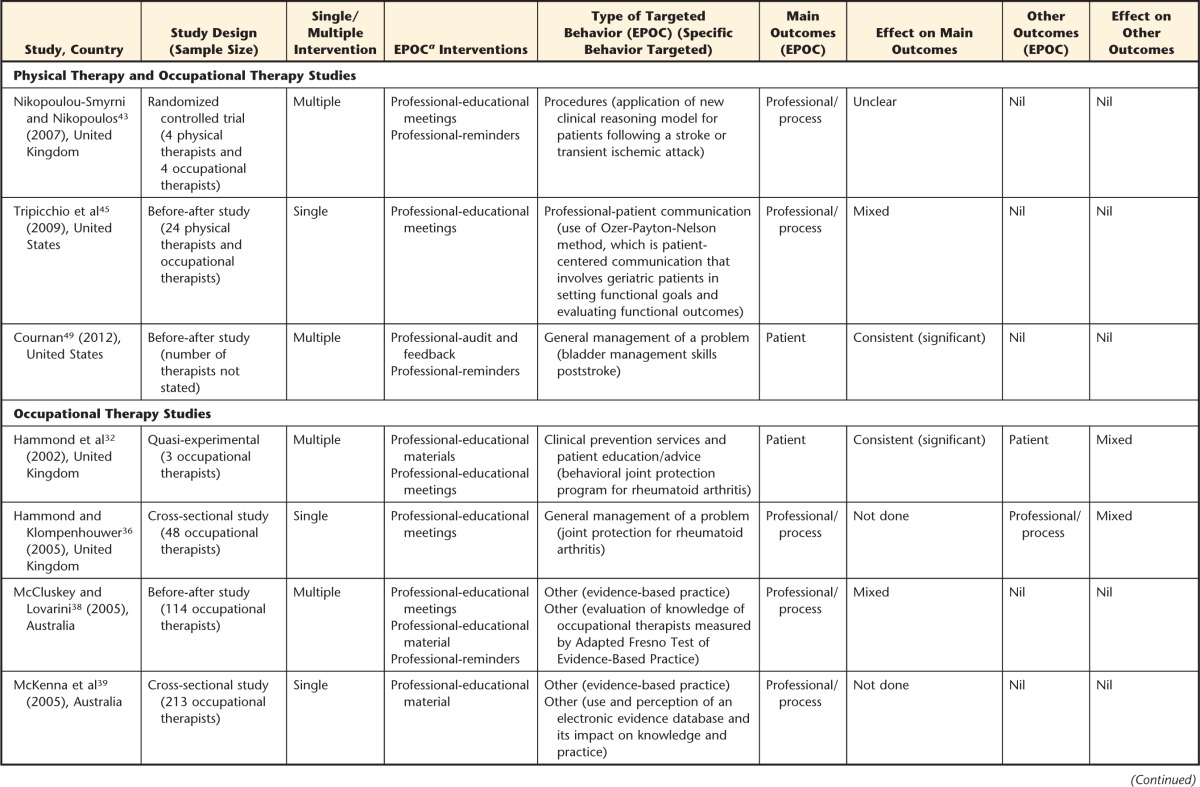

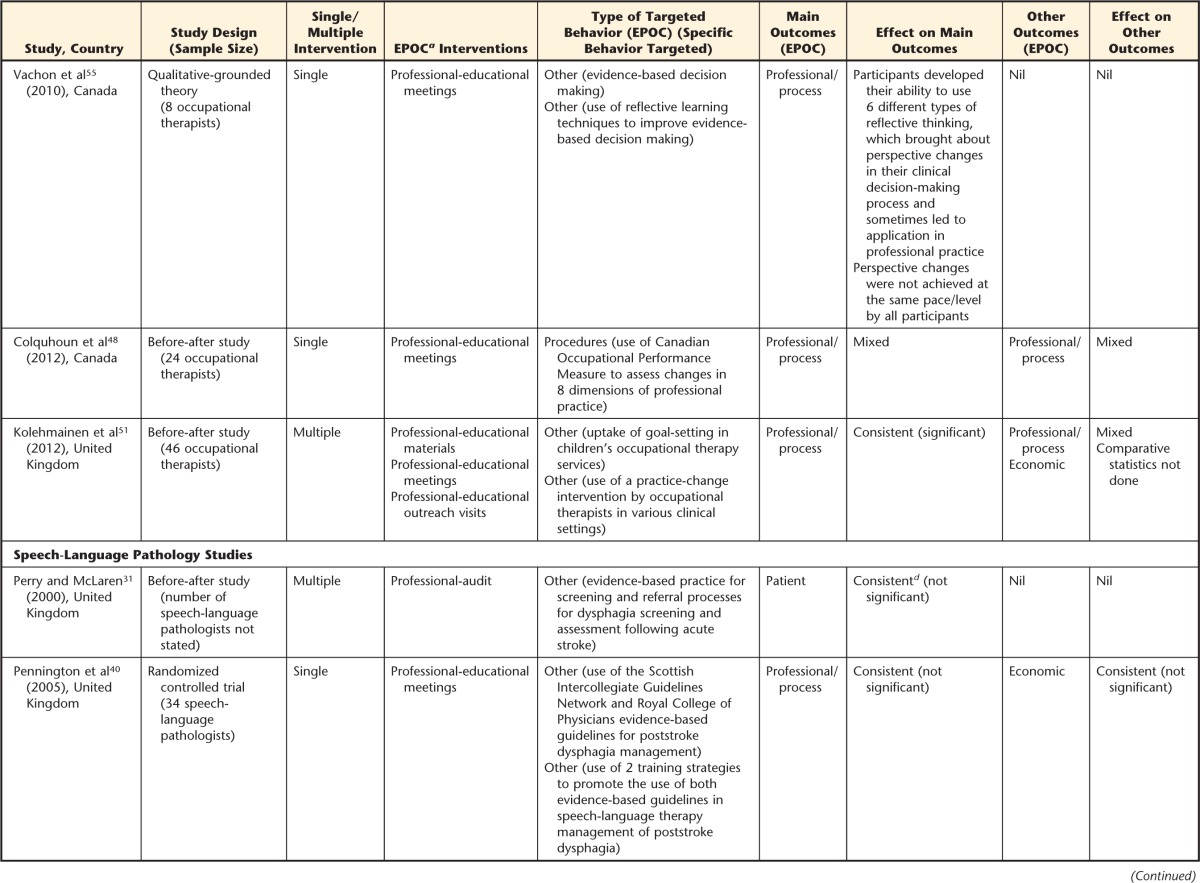

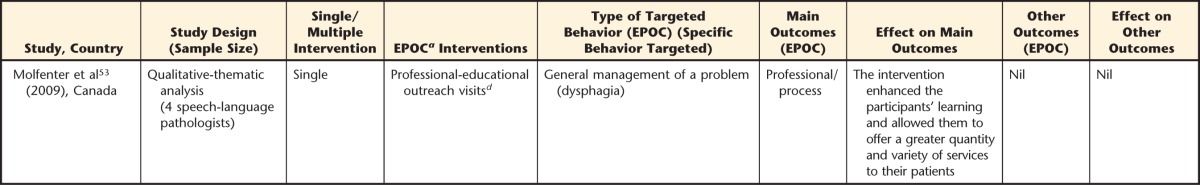

Of the 26 studies that met our inclusion criteria (Figure), 23 were quantitative studies30–52 and 3 were qualitative studies.53–55 Of the 26 studies, 2 studies produced multiple papers.33,34,37,52,54 Within each profession, the heterogeneity of the study designs, KT interventions, targeted behaviors, and study outcomes precluded combining comparable results. Table 2, which summarizes the 26 studies, includes important study elements and is organized by discipline. The included studies for this review were completed in 6 countries, with the greatest number being from the United Kingdom (27%). Thirteen studies (50%) targeted physical therapy, 7 studies targeted occupational therapy, 3 studies examined interventions for both physical therapy and occupational therapy, and another 3 studies targeted speech-language pathology. An additional 9 articles were identified with the updated review.31,32,46–52

Figure.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies

a EPOC=Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group.

b 3 papers derived from one study.

c 2 papers derived from one study.

d The intervention had an additional component that cannot be classified within the EPOC framework.

KT Interventions

As shown in Table 2, 9 studies investigated a single KT intervention, of which 1 was a physical therapy study,30 4 were occupational therapy studies,36,39,48,55 1 included both occupational and physical therapy,45 and 2 were speech-language pathology studies.40,53 Following the EPOC classification scheme, the predominant single KT intervention was educational meetings,30,36,40,45,48,55 followed by educational materials39 and educational outreach visits.53

Eighteen studies examined multiple KT interventions, with the majority targeting physical therapy,33–35,37,41,42,44,46,47,50,52,54 3 involving occupational therapy,32,38,51 2 investigating both occupational therapy and physical therapy,43,49 and 1 targeting speech-language pathology.31 The studies using multiple interventions all contained at least one education-related component. Ten of these studies used education interventions exclusively: educational meeting and educational material32–34,37,46,47,54; educational outreach visit and educational material35; and educational meeting, educational outreach visit, and educational material.41,51 Seven studies using multiple interventions represented the following combinations: educational meeting and reminders,43 educational meeting and local opinion leaders,42 educational meeting and material and local opinion leader,44 educational meeting and material and reminders,38 educational meeting and material and audit and feedback,50 educational meeting and material and local consensus,52 and reminders and audit and feedback.49

KT Outcomes

Because the studies assessed different outcomes, we applied the EPOC classification scheme. The primary type of outcome used was professional/process outcomes,30,33,35,36,38–40,42–48,50–55 followed by studies that used patient outcomes31,32,34,41,49 and one study that used economic outcomes.37 Studies that included physical therapy identified a wide range of outcomes, including: professional/process (n=12),30,33,35,42–47,50,52,54 patient,34,41 and economic evaluations of the KT interventions.37 The outcomes were typically used with therapists from musculoskeletal or pediatrics settings.

Effectiveness of KT Interventions

Main outcomes.

As described in Table 2, fewer than half of the quantitative studies (n=12) showed a consistent effect on the primary outcome measures30–35,40,41,47,49,51; however, 5 studies demonstrated effects that were not statistically significant.30,34,40,41,51 Two studies demonstrated consistent, significant positive effects on primary outcomes (P<.05).33,35 More specifically, these 2 studies reported improved behavior change with multicomponent KT interventions directed at physical therapy for treating patients with lower back pain and fall strategies. Of the remaining quantitative studies, 4 studies demonstrated mixed effects, which included 2 randomized controlled trials,37,42 and 6 studies used a before-after study design.38,45,46,48,50,52 Four studies could not be classified as having consistent or mixed effects on the primary outcome measures because no statistical testing was reported.36,39,43,44

Other outcomes.

Other or secondary outcomes were reported in 12 of the 23 quantitative studies30,32,35–37,40,41,44,46,48,50,51 and included 5 professional/process outcomes,35,36,46,48,50 3 patient outcomes,30,36,37 2 economic outcomes,40,44 and 2 professional/process with economic outcomes.41,51 None of these studies demonstrated a consistent, statistically significant positive effect; however, 4 studies demonstrated consistent, statistically nonsignificant effects on secondary outcome measures.30,40,41,44 Eight studies showed mixed effects.32,36,37,41,46,48,50,51 Two studies did not provide comparative statistics and were classified as “not done.”35,51

Effect of intervention by profession.

When the intervention effects were examined by profession, 2 physical therapy studies,33,35 2 occupational therapy studies,32,51 and 1 combined physical therapy and occupational therapy study49 demonstrated consistent, statistically significant positive effects on primary outcome measures. These studies investigated primarily multicomponent interventions that dealt with educational meetings, materials, and outreach visits in the community and in rehabilitation settings. The studies with consistent, nonsignificant effects on primary outcome measures included physical therapy30,34,41 and speech-language pathology.31,40 Mixed effects also were reported for the primary outcome measures in studies that examined physical therapy,37,42,46,50,52 occupational therapy,38,48 and both physical therapy and occupational therapy.45

Intervention Evaluation in Qualitative Research Studies

The 3 qualitative studies included physical therapy,54 occupational therapy,55 and speech-language pathology.53 These studies used both single and multiple education-related KT interventions targeting general management of a problem or evidence-based practices. The behavior changes in all 3 studies were evaluated using the professional/process outcomes. Although there were some encouraging findings, such as sustained positive attitudes and beliefs, ability to use different types of reflective thinking, and enhanced learning and services, all of the studies acknowledged variable practice changes related to the targeted behaviors.

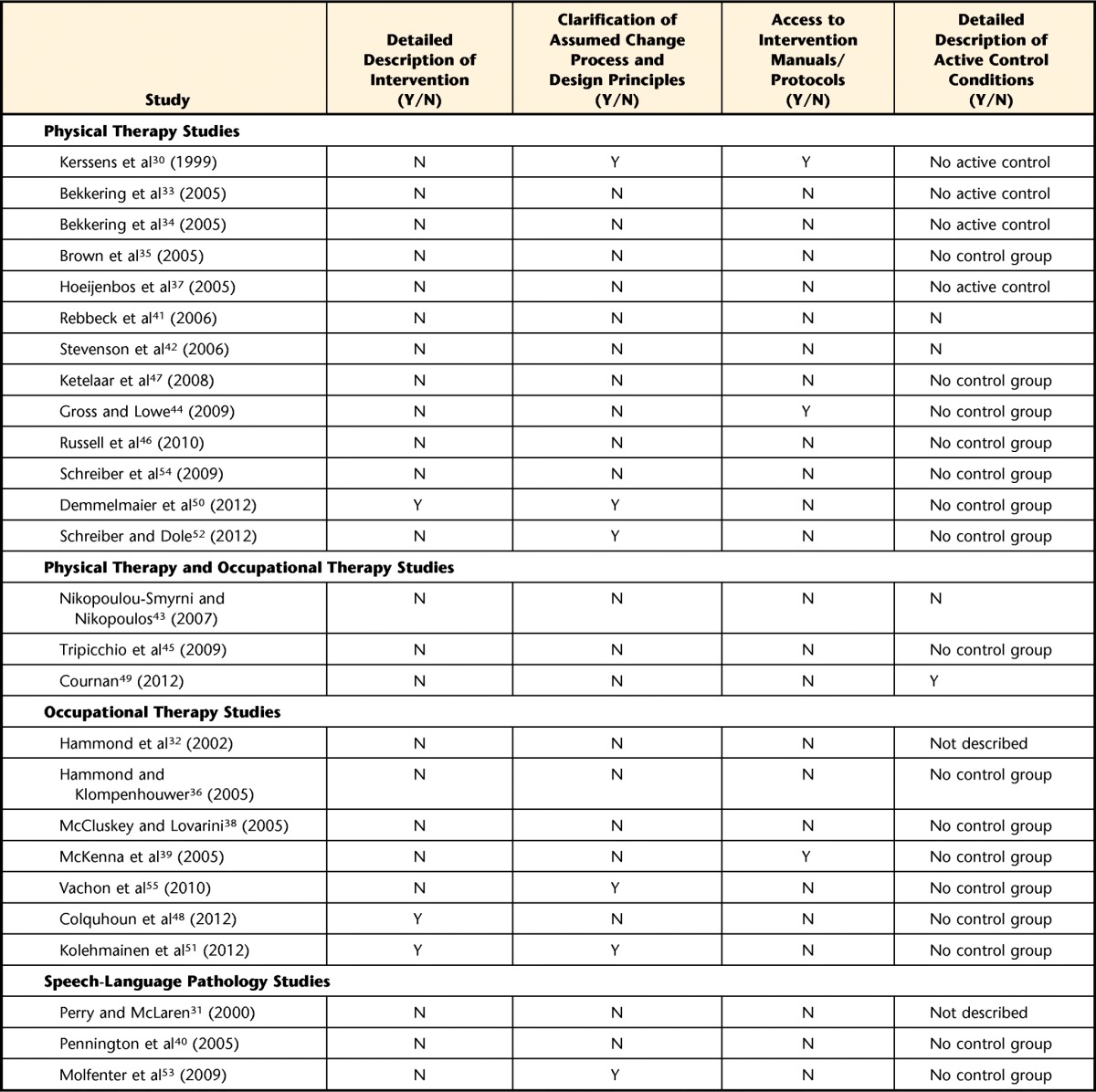

Published Intervention Reporting

Because the quality and detail of reporting for the KT interventions varied widely among the 26 studies, the published intervention descriptions were compared to the WIDER Recommendations to Improve Reporting of the Content of Behaviour Change Interventions (Tab. 3). While a small number of studies met 2 of the 4 criteria,30,50,51 none of the 26 studies satisfied all four of the WIDER recommendations. Evaluation of criteria was dependent upon the detail included in the studies. Many of the studies described components of the first recommendation, such as descriptions of intervention recipients, the intervention setting, the mode of delivery, and the intensity and duration of the intervention. Nevertheless, 3 more recent studies provided a full and detailed description,48,50,51 which included a description of the characteristics of the individuals delivering the intervention, the adherence or fidelity to delivery protocols, and a detailed description of intervention content.

Table 3.

Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) Recommendations to Improve Reporting of the Content of Behavior Change Interventionsa

Y=yes, N=no.

The second WIDER recommendation, which details the clarification of the assumed changed process and design principles, was described in 6 studies.30,50–53,55 Several studies included a description of a theoretical framework informing their research, the rationale behind and impetus for the intervention, and the behavior that the intervention was intended to change; however, most did not describe the development of the intervention, the change techniques used in the intervention, or the causal processes targeted by these change techniques.31–49,54

Only 3 studies fulfilled the third recommendation of providing access to intervention manuals or protocols within the article or in separate publications.30,39,44 One physical therapy and occupational therapy study included an active control for the intervention group.49 Most studies were exempt from the fourth recommendation because the study designs did not include a control group35,36,38–40,44–48,50–55 or active control conditions.30,33,34,37

Methodological Quality

Based on the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, none of the quantitative studies received a strong rating, although 3 studies received a moderate rating34,42,45 and the remaining studies received weak ratings.30–33,35–41,43,44,46–52 Those studies that demonstrated consistent, significant positive effects on the primary outcomes, in effect showing that the KT intervention changed the behaviors, all received a weak rating.32,33,35,49,51 The qualitative studies were reviewed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Qualitative Studies, with 1 qualitative study attaining the highest rating of 555 and the other 2 studies receiving lower scores of 254 and 1.53

Discussion

This systematic review showed that educational meetings were commonly used KT strategies specifically directed at translating research into practice and enhancing research uptake in rehabilitation disciplines. Many studies, however, used more passive approaches in that educational meetings and materials were used rather than active approaches such as use of an opinion leader, which by definition is a person typically nominated by his or her colleagues as “educationally influential.”28 Audit and feedback is another example of an active KT approach. This approach is a summary of clinical performance of health care over a specified period of time and includes recommendations for clinical action.28 Our review identified articles primarily in physical therapy and occupational therapy that focused on professional interventions such as clinical guidelines and clinical prevention services. The recent articles tended to be similar to the articles identified in the original search in that the interventions primarily were educational meeting and materials. Although this review complements the work done in medicine and nursing,7,16,56 the KT strategies used in medicine may not directly translate to the rehabilitation professions given the different nature and structure of rehabilitation professionals' work; the relatively small number of clinicians in physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language pathology; and the diverse environments and scope that therapists practice. Other authors also have recognized the complex system of translating knowledge into the rehabilitation clinical context, which includes the values of the client, therapist, and research knowledge.57,58

The findings build upon the work by Menon and colleagues,8 who reported that active multicomponent KT strategies were effective in physical therapy knowledge and practice behaviors. We also found that active multicomponent strategies were used in physical therapy and occupational therapy, yet very few articles examined KT interventions in speech-language pathology, of which only one study was multicomponent. Although the majority of studies were quantitative, the methodological rigor of most studies was weak. For instance, discrepancies were seen between the outcomes reported in the “Method” and “Results” sections. Furthermore, inconsistencies were seen with the use of multiple tools and approaches to evaluate the primary outcome. These inconsistencies made methodological evaluation challenging and point to deficiencies in the overall reporting of research. Overall, the effectiveness of the KT strategies was not significant and may be reflective of the methodological rigor and quality of research reporting.

The findings from this review provide evidence of the growing literature of KT strategies used in rehabilitation. Within this systematic review, we examined all types of KT interventions that took the current best evidence to clinical practice. Our inclusion criteria were inclusive of all study designs rather than limiting the designs to randomized controlled trial and observational study designs. Professional education was a common intervention used in all 3 rehabilitation disciplines that also was seen with more recent articles retrieved with the updated review. The use of educational strategies is not limited to rehabilitation but is also seen in nursing and medicine.6,7 Included studies that used a single KT intervention evaluated education-only approaches, which generated nonsignificant findings. Given this finding, single KT interventions other than education (eg, local opinion leaders, audit and feedback, reminders) should be investigated in rehabilitation.

Most studies in this systematic review used a multicomponent KT strategy, which was encouraged by other authors.5,8,16 The effectiveness of single or multicomponent interventions, however, is not clearly delineated in the literature. Although other authors have reported modest improvements with multicomponent interventions such as educational materials and audit and feedback,56 no clear dose-response relationship between the number of interventions and the effect size of the outcome has been reported.6 Grimshaw et al cautiously suggested, “multifaceted interventions built upon careful assessment of barriers and coherent theoretical base may be more effective than single interventions.”59 Multicomponent interventions that target or have been tailored to overcome the barriers specific to clinical practice may be effective strategies in changing behavior. Although evidence indicates that rehabilitation professionals are motivated to learn as practicing professionals,60–62 institutional barriers, resistance to change, and lack of confidence in evaluating the evidence were reported as barriers to evidence-based practice.11,62 The implementation of multicomponent interventions, however, warrants practical considerations, given the additional costs, time, and resources to implement. Active strategies are more expensive to implement, yet economic evaluations of effective strategies are needed to demonstrate the value of implementing KT interventions. Within this review, one study's primary outcome did address the economic implications of guidelines for low back pain management.37

Despite the strengths of this review, limitations should be noted. A wide range of studies was included in this review; however, the heterogeneity of the studies was not conducive to pooling the data in a meta-analysis. Because of the diversity, we were incapable of providing definite recommendations based on these articles. Furthermore, much of the literature included in the review was of moderate or weak quality. These findings underscore the gaps in KT strategies used in rehabilitation, provide guidance to implementation of future studies of KT interventions in rehabilitation, and highlight the need for rigorously designed studies that are well reported.

In this review, we have identified studies that examined KT strategies within rehabilitation. Our review demonstrated a growing awareness of KT within the rehabilitation professions, as evidenced by increased number of KT papers published in recent years. Although the studies examining physical therapy and occupational therapy used passive multicomponent approaches in the form of education, great variation existed in the implementation and documentation of these interventions. Barriers to change in behavior provide valuable insight into the type of KT strategies, which will be effective in the diverse practice settings of rehabilitation professionals. Implementing evidence-based findings into clinical practice is a complex process that will require well-thought, diverse strategies specific to the scope of practice, knowledge, and values.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Dr Scott conceptualized the original study spanning 5 disciplines (upon which this review is based) and secured study funding from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). She designed and led the original study. Dr Jones designed this component review, which focused on the 3 rehabilitation disciplines. Dr Jones also led the replication and extension (by date) of the original review by Dr Scott and colleagues with contributions by Dr Scott and Ms Albrecht. Dr Jones, Mr Roop, and Dr Pohar collected and analyzed the review data for this component review. All authors contributed to manuscript drafts and reviewed the final manuscript. The authors thank the team at Alberta Research Centre for Health Evidence (ARCHE) at the University of Alberta for assisting with the review process in the original review, and special gratitude is expressed to Thane Chambers, MLIS, for her assistance and guidance with the search.

The authors thank CIHR (Knowledge Synthesis Grant KRS 102071) and Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions (establishment grant to Dr Jones) for providing the funding for this project. Dr Scott and Dr Jones held the CIHR New Investigator Award and Population Health Investigator Award from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (now Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions). Dr Scott currently holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) for Knowledge Translation in Child Health.

References

- 1. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312:71–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research. FOCUS Technical Brief 10: what is knowledge translation? FOCUS. 2005;10:1–4 Available at: http://www.ktdrr.org/ktlibrary/articles_pubs/ncddrwork/focus/focus10/Focus10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gross DP. Knowledge translation and behaviour change: patients, providers, and populations. Physiother Can. 2012;64:221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lencucha R, Kothari A, Rouse MJ. The issue is…knowledge translation: a concept for occupational therapy? Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:593–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, et al. ; the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998;317:465–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii–iv, 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thompson DS, Estabrooks CA, Scott-Findlay S, et al. Interventions aimed at increasing research use in nursing: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2007;2:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N, Kastner M, et al. Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott SD, Albrecht L, O'Leary K, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012;7:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rogers JD, Martin FH. Knowledge translation in disability and rehabilitation research: lessons from the application of knowledge value mapping to the case of accessible currency. J Disabil Policy Studies. 2009;20:110–126. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Metcalfe C, Lewin R, Wisher S, et al. Barriers to implementing the evidence base in four NHS therapies: dietitians, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists. Physiotherapy. 2001;87:433–441. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis D, Evans M, Jadad A, et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect. BMJ. 2003;327:33–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colquhoun HL, Letts LJ, Law MC, et al. A scoping review of the use of theory in studies of knowledge translation. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77:270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC). Data Collection Checklist. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Institute of Population Health; 2002. Available at: http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grol R, Grimshaw JM. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas RE, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39:II2–II45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scott-Findlay S, Golden-Biddle K. Understanding how organizational culture shapes research use. J Nurs Admin. 2005;35:359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newton MS, Scott-Findlay S. Taking stock of current societal, political and academic stakeholders in the Canadian healthcare knowledge translation agenda. Implement Sci. 2007;2:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scott SD, Albrecht L, O'Leary K, et al. A protocol for a systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morrison A, Moulton K, Clark M, et al. English-Language Restriction When Conducting Systematic Review-Based Meta-Analyses: Systematic Review of Published Studies. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hartling L, Bond K, Santaguida PL, et al. Testing a tool for the classification of study designs in systematic reviews of interventions and exposures showed moderate reliability and low accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER). WIDER Recommendations to Improve Reporting of the Content of Behaviour Change Interventions: WIDER Consensus Statement. 2008. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/supplementary/1748-5908-7-70-s4.pdf Accessed June 16, 2014.

- 24. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Effective Public Health Practice Project. 2003. Available at: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html.

- 26. Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs, 2004;1:176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hutchinson AM, Mallidou AA, Toth F, et al. Review and Synthesis of Literature Examining Characteristics or Organizational Context That Influence Knowledge Translation in Healthcare: Technical Report. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC). Cochrane Collaboration on Effective Professional Practice. Data Collection Checklist. The Cochrane Library. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review: a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kerssens JJ, Sluijs EM, Verhaak PFM, et al. Educating patient educators: enhancing instructional effectiveness in physical therapy for low back pain patients. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perry L, McLaren SM. An evaluation of implementation of evidence-based guidelines for dysphagia screening and assessment following acute stroke: phase 2 of an evidence-based practice project. J Clin Excellence. 2000;2:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hammond A, Jeffreson P, Jones N, et al. Clinical applicability of an educational-behavioural joint protection programme for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Occup Ther. 2002;65:405–412. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bekkering GE, Hendriks HJ, van Tulder MW, et al. Effect on the process of care of an active strategy to implement clinical guidelines on physiotherapy for low back pain: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bekkering GE, van Tulder MW, Hendriks EJ, et al. Implementation of clinical guidelines on physical therapy for patients with low back pain: randomized trial comparing patient outcomes after a standard and active implementation strategy. Phys Ther. 2005;85:544–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown CJ, Gottschalk M, Van Ness PH, et al. Changes in physical therapy providers' use of fall prevention strategies following a multicomponent behavioral change intervention. Phys Ther. 2005;85:394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hammond A, Klompenhouwer P. Getting evidence into practice: implementing a behavioural joint protection education programme for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Occup Ther. 2005;68:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoeijenbos M, Bekkering T, Lamers L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an active implementation strategy for the Dutch physiotherapy guideline for low back pain. Health Policy. 2005;75:85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McCluskey A, Lovarini M. Providing education on evidence-based practice improved knowledge but did not change behaviour: a before and after study. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McKenna K, Bennett S, Dierselhuis Z, et al. Australian occupational therapists' use of an online evidence-based practice database (OTseeker). Health Inf Libr J. 2005;22:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pennington L, Roddam H, Burton C, et al. Promoting research use in speech and language therapy: a cluster randomized controlled trial to compare the clinical effectiveness and costs of two training strategies. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rebbeck T, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Evaluating two implementation strategies for whiplash guidelines in physiotherapy: a cluster-randomised trial. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stevenson K, Lewis M, Hay E. Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based educational programme? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nikopoulou-Smyrni P, Nikopoulos CK. A new integrated model of clinical reasoning: development, description and preliminary assessment in patients with stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gross DP, Lowe A. Evaluation of a knowledge translation initiative for physical therapists treating patients with work disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:871–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tripicchio B, Bykerk K, Wegner C, Wegner J. Increasing patient participation: the effects of training physical and occupational therapists to involve geriatric patients in the concerns-clarification and goal-setting processes. J Phys Ther Educ. 2009;23:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Russell DJ, Rivard LM, Walter SD, et al. Using knowledge brokers to facilitate the uptake of pediatric measurement tools into clinical practice: a before-after intervention study. Implement Sci. 2010;5:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ketelaar M, Russell DJ, Gorter JW. The challenge of moving evidence-based measures into clinical practice: lessons in knowledge translation. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2008;28:191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Colquhoun HL, Letts LJ, Law MC, et al. Administration of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: effect on practice. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79:120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cournan M. Bladder management in female stroke survivors: translating research into practice. Rehabil Nurs. 2012;37:220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Demmelmaier I, Denison E, Lindberg P, Asenlof P. Tailored skills training for practitioners to enhance assessment of prognostic factors for persistent and disabling back pain: four quasi-experimental single-subject studies. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012;28:359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kolehmainen N, MacLennan G, Ternent L, et al. Using shared goal setting to improve access and equity: a mixed methods study of the Good Goals intervention in children's occupational therapy. Implement Sci. 2012;7:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schreiber J, Dole RL. The effect of knowledge translation procedures on application of information from a continuing education conference. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2012;24:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Molfenter SM, Ammoury A, Yeates EM, Steele CM. Decreasing the knowledge-to-action gap through research: clinical partnerships in speech-language pathology. Can J Speech Lang Pathol Audiol. 2009;33:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schreiber J, Stern P, Marchetti G, Provident I. Strategies to promote evidence-based practice in pediatric physical therapy: a formative evaluation pilot project. Phys Ther. 2009;89:918–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vachon B, Durand MJ, LeBlanc J. Using reflective learning to improve the impact of continuing education in the context of work rehabilitation. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:329–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Grimshaw JM, Eccles M, Thomas RE, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement: evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 2):S14–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Metzler MJ, Metz GA. Translating knowledge to practice: an occupational therapy perspective. Aust Occup Ther J. 2010;57:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hakkennes S, Dodd K. Guideline implementation in allied health professions: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, et al. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rappolt S, Tassone M. How rehabilitation therapists gather, evaluate, and implement new knowledge. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22:170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Humphries D, Littlejohns P, Victor C, et al. Implementing evidence-based practice: factors that influence the use of research evidence by occuptional therapist. Br J Occup Ther. 2000;63:516–522. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bennett S, Tooth L, McKenna K, et al. Perceptions of evidence-based practice: a survey of Australian occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2003;50:13–22. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.