Abstract

Density of foods is an important physical property, which depends on structural properties of food. For porous foods such as baked foods, accurate measurement of density is challenging since traditional density measurement techniques are tedious, operator-dependent and incapable of precise volume measurement of foods. To overcome such limitations, a methodology was developed using both digital radiography(DR) and computed tomography(CT) x-ray imaging to directly determine density of foods. Apparent density was determined directly from x-ray linear attenuation coefficients by scanning at 40, 60, 80 kVp on DR and 45, 55, 70 kVp on CT. The apparent density can be directly determined using CT however sample thickness is needed to determine density using DR. No significant difference (p<0.05) was observed between density obtained from traditional methods, with density determined from x-ray linear attenuation coefficients. Density determined on CT for all foods with mean 0.579 g/cm3 had a standard deviation, SD = 0.0367 g/cm3. Density determination using x-ray linear attenuation was found to be a more efficient technique giving results comparable with conventional techniques.

Keywords: Apparent density, porous foods, x-ray imaging, digital radiography, computed tomography, x-ray linear attenuation coefficient

1. Introduction

Density of foods is a physical property that is used to determine quality of foods and many-a-times used as a conversion factor to determine volume of foods. There are several measurement techniques for density that involve separately determining mass and volume of the food sample. However, traditional volume measurement is commonly associated with drawbacks such as repeated calibration, laborious, inaccuracy and subject to operator dependence (Rahman 2009). Solid displacement technique using rapeseed commonly used for volume determination of baked foods (AACC, 2000) encounters a number of such problems and more including seed clutter, sticking of seed to food, seed clumping and the subsequent need for cleaning of seeds before reuse. This necessitates the need for a more reliable and efficient method to directly determine density of any food materials.

Numerous non-destructive imaging methods have been developed in recent decades for the evaluation of foods. Imaging techniques can now characterize food products based on physical, mechanical, optical, electro-magnetic, thermal properties (Gunasekaran, 1985, Kotwaliwale et al., 2011, Kelkar et al., 2011). But none have been developed that can directly determine the density of foods. Since absorption of x-rays are directly proportional to the material's inherent density (Phillips and Lannutti, 1997) this work proposes a methodology using x-ray imaging technology for the direct measurement of density of foods X- ray imaging has been widely used in the food industry for quality control purposes (Haff & Toyofuko, 2008). In x-ray digital radiography (DR), a single image consisting of a projection of transmitted x-rays through an object is acquired. DR is widely used commercially for the detection of contaminants in foods (Nicolai et al., 2014). A few studies have employed DR for the investigation of infestation damage in fruits (Jiang et al, 2008) and understanding quality attributes of nuts (Kim & Schatzki, 2001). Recently, computed tomography (CT) has been proven to be a useful technique for quantitative and qualitative analysis of the constituents of many food items. It has been used to quantitatively analyze the geometrical distribution of fat and proteins in meat products (Frisullo, 2009), to understand the role of sugar and fat in cookies (Pareyt et al, 2009), apple tissue (Mendoza et al., 2007), and to investigate the rise of dough (Bellido, 2006). Recently, micro CT was used to generate high-resolution 2D and 3D microstructures of bread (Besbes et al., 2013; Cafarelli et al., 2014; Demirkesen et al., 2014; Van Dyck et al., 2014), and extruded starch products (Horvat et al., 2014) in order to characterize the structure of product to its ingredients properties, or processing conditions. In all these cases, image processing tools and algorithms were utilized to quantify structural characteristics of the food products.

In medical physics, CT has been commonly used for diagnosis based on relative changes in attenuation contrast. Absolute values of attenuation are used only for calcium recording based on thresholding techinique, and bone densiometry where calibrated tables are used to determine density values (Heismann et al., 2003). Monte Carlo algorithms relating tissue density to Housenfield CT numbers (Schneider et al., 2000) and electron density, atomic number using dual-energy CT (Hünemohr et al., 2014) have been demonstrated. However little or no work has focused on using x-ray imaging to directly determining the density of a wide range of foods.

1.1 Theory

Beer-Lambert's law relates the absorption of light to the material through which the light passes. Similarly, the absorption of x-rays is related to the material through which the beam passes by the following equation (Jackson & Hawkes, 1980),

| (1) |

Where I = intensity of transmitted x-rays

I0 = intensity of incident x-rays

μ = linear attenuation coefficient of the material

t = thickness of material through which x-rays have traveled

The linear attenuation coefficient (μ) of a material responsible for the x-ray image contrast is dependent on the density of a material (Falcone et al., 2005).

The Beer-Lambert's law is ideally valid for monochromatic x-ray source since low energy x-ray beams are more strongly adsorbed than the higher energy beams. For polychromatic sources, it results in attenuation of a homogenous sample being not proportional to its thickness. This produces distortions and false density gradients due to the hardening of the beam. Hence, polychromatic x-ray sources normally used in commercial X-ray devices filter out low energy x-rays and apply mathematical algorithms to correct such artifacts (Busignies et al., 2006).

X-ray attenuation for energies, E< 511k eV is due to the principle mechanisms of photoelectric absorption, Compton scattering, and Rayleigh scattering (Cho et al., 1975). X-ray attenuation is dominated by both Compton scattering and photoelectric absorption, while Rayleigh scattering photon interaction is negligible (Phillips and Lannutti, 1997). Thus, the total spectral attenuation as given by Heismann et al. (2003) is,

| (2) |

Where μ is the linear attenuation coefficients at x-ray energy level E

= Photoelectric absorption term

βρ = Compton Scattering term

Z = atomic number of the absorber

β = scattering attenuation constant

and α = photoelectric constant

Typically k = 3 (Heismann et al., 2003); l = 3.1 (Cho et al., 1975); and β ≈ 0.02 m2/kg for E < 140 keV (Heismann et al., 2003)

1.2 Density measurement

1.2.1 Linear attenuation coefficient method

Linear attenuation coefficient can be normalized by dividing it by the density (ρ) of the element or compound, results in (μ/ρ), a constant known as the mass attenuation coefficient (cm2/g) (Bushberg, 2002) for any given material at a given energy level. Thus, the mass attenuation coefficient is only dependent on the composition of a given material and independent of density while linear attenuation coefficient increases with increasing density.

The density of a material can be determined from the linear attenuation coefficients of the sample measured at two different x-ray energies E1 and E2,

Given that at E1,

| (3) |

And at E2

| (4) |

Since Zk is constant at all energy levels for a given material, and since β and l are constant for all materials, equating equations (3) and (4),

| (5) |

| (6) |

Rearranging in terms of density,

| (7) |

Where

| (8) |

The linear attenuation coefficient method gives the basic x-ray absorption equation (7) that shows apparent density is a direct function of the x-ray linear coefficients determined at least two different energies. This energy dependence of μ depends on the principle shown by Heismann et al. (2003) where density is expressed as a direct function of two attenuation values μ1 and μ2 obtained at two different energies E1 and E2 with different spectral weighting.

1.2.2 Intercept method

Density can also be determined from the intercept of equation (2) determined at various energy levels. The term ραZk is the slope, with the Compton Scattering term βρ being the intercept. Since β is a constant and independent of the material, the apparent density (ρ) can thus be determined.

Although direct determination of density using x-ray radiography (DR) requires the knowledge of thickness of the food material, this limitation can be overcome by using computed tomography (CT), which can determine linear attenuation through a material at any thickness. Since most industrial DRs and CTs contain filters at the x-ray source and detector to eliminate any lower energy photons to avoid beam hardness with the object, precise reproducibility that can be obtained in its measurements over a large number of scans (Phillips and Lannutti, 1997).

1.3 Objective

The main objective of the study is to develop a methodology to directly determine apparent density of foods using x-ray imaging systems such as x-ray radiography and computed tomography. The relationship of x-ray linear attenuation coefficient of a food with x-ray energy was used to directly determine apparent density.

2. Materials

Both porous and non-porous food samples used for density determination. The apparent density of porous food samples (breads, cookies) were externally determined in triplicate from the volume calculated from the characteristic dimensions measured using a vernier caliper (Mitutoyo Corp, USA). The non-porous foods such as tomato paste, mayonnaise, and soybean oil, were also evaluated to validate the accuracy of density measurement on CT. For these foods, apparent density was externally determined in triplicate using an aluminum-alloy pycnometer (Cole Parmer, IL).

3. Methods development

The use of x-ray imaging for quantitative analysis requires the validity of Beer-Lambert's law. Non-linearity of x-ray attenuation leads to numerous artifacts such as beam hardening resulting in false density gradients, which can affect the quantitative measurements (Busignies et al., 2006). Hence, verification of Beer-Lambert's law was done for both x-ray imaging systems. To determine apparent density using x-ray imaging, procedures were developed to determine x-ray linear attenuation coefficient (μ), Compton scattering coefficient (β), and x-ray system energy and energy weighting ratio, c of equation (7) for each system.

3.1 μ from x-ray digital radiography (DR)

Bread samples were scanned on x-ray digital radiograph (DR), RapidStudy EDR6 (Sound-Eklin, CA) at 40, 60 and 80 kVp energy levels and 2.5 milli- Ampere - seconds. In x-ray scans involving foods, several thicknesses of the samples were placed along with an empty container and a container of distilled water to act as controls. X-ray images were exported and processed using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Each sample was segmented and its x-ray intensity (-ln I/I0) was determined from gray scale values of the sample and control. The intensity was plotted against sample thickness to obtain the linear attenuation coefficients (μ) of the sample at that particular energy to verify compliance with Beer-Lambert's law.

3.2 μ from Computed Tomography (CT)

MicroCT 40 (Scano Medical Inc.,PA) was used to obtain CT data at 45, 55 & 70 kVp. Cotton was placed on top and below the solid sample in the cell to ensure no movement of sample during scanning. The sample cell was covered with a paraffin film to avoid possible moisture loss. Each sample was scanned to obtain 100 CT-slices of 0.036mm thickness. The linear attenuation coefficient (μ) was obtained directly from the microCT reconstruction software for every slice at a given energy level. Mean linear attenuation coefficient of a sample was determined at each energy level.

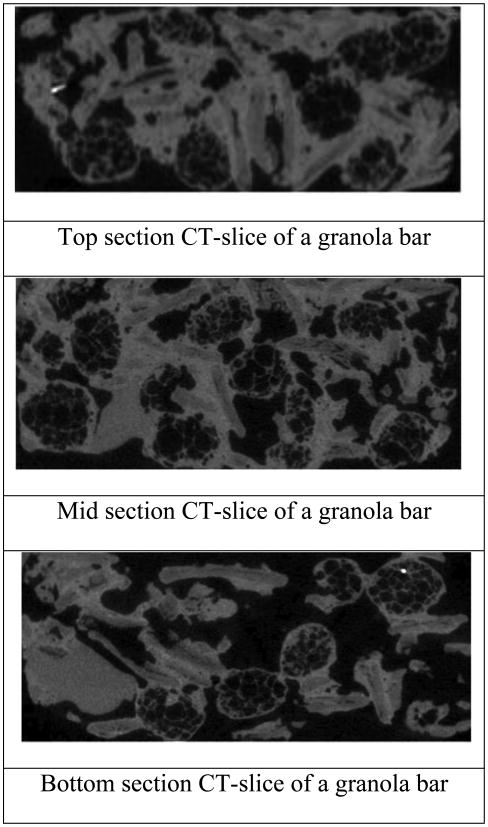

To determine the number image slices needed to accurately evaluate a sample; a granola bar comprising of variable internal structure was scanned using the maximum number of imaging slices. Figure 2 shows three CT-slices of different regions in a granola bar demonstrating the variation of internal structure. On scanning the granola bar having a diverse and non-uniform structure, 2030 CT-slices (∼0.007 mm/ slice thickness) were obtained characterizing the whole sample. The value of μ obtained for 2030 CT-slices at 45 kVp energy level was determined to be not significantly different (p<0.05) than the μ obtained for 100 CT-slices(∼0.036 mm/ slice thickness) at 45 kVp. Thus, 100 CT-slices were selected to be satisfactorily representative of the sample due to reduced processing time for the remaining study.

Figure 2. Examples of CT-slices of a whole granola bar scanned on a micro CT.

3.3 Determination of Compton scattering coefficient, β

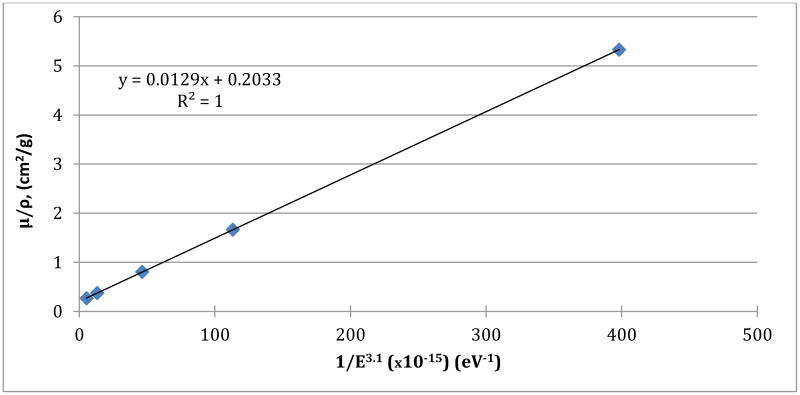

Compton scattering coefficient, β, which is independent of the material being tested, was calculated using values of μ/ρ, for photon energies 10k to 40k eV (equivalent to x-ray voltages) for water documented by National Institute of Standards & Technology (NIST) (http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xraycoef/index.cfm). By rearranging equation (2), and substituting l =3.1 (Cho et al., 1975), the following equation is obtained,

| (9) |

Where

| (10) |

The NIST values for water at energy levels between 10-40 eV were substituted in the equation (9) above, and plotted to determine the value of intercept, i.e. Compton scattering attenuation coefficient, β and slope, m = αZk (Fig 1). As per the equation (9), β = 0.2033 cm2/g and slope, m = αZk = 1.29 × 1013 (R2= 1) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mass attenuation coefficient of water (μ/ρ) from NIST, against corresponding photon-energies, E (10k -40k eV) to obtain the Compton scattering coefficient (β) as the resulting intercept according to equation (10).

3.4 Determination of x-ray system energy weighting ratio, c

The x-ray system energy weighting ratio c (function of x-ray source and detector) was determined from equation (6) using distilled water as a standard for both DR and CT at two energy levels for each sample run. The value of c was determined before every experimental sample run using distilled water to ensure standardization. The x-ray linear attenuation values (μ) for distilled water determined at various tube voltages, the known density of water (ρ) and β (from Fig.1) were substituted in equation (6) to obtain the values of for the particular pair of tube voltages. Thus a direct relationship between apparent density of the material (ρ) and x-ray linear attenuation coefficients (μ) described in equation (7) was obtained.

Statistical software JMP 5.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct analysis of variance data. Least significant differences were calculated to compare mean values, with significance defined at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion of results

4.1 Apparent density using x-ray linear attenuation coefficient on digital radiography (DR)

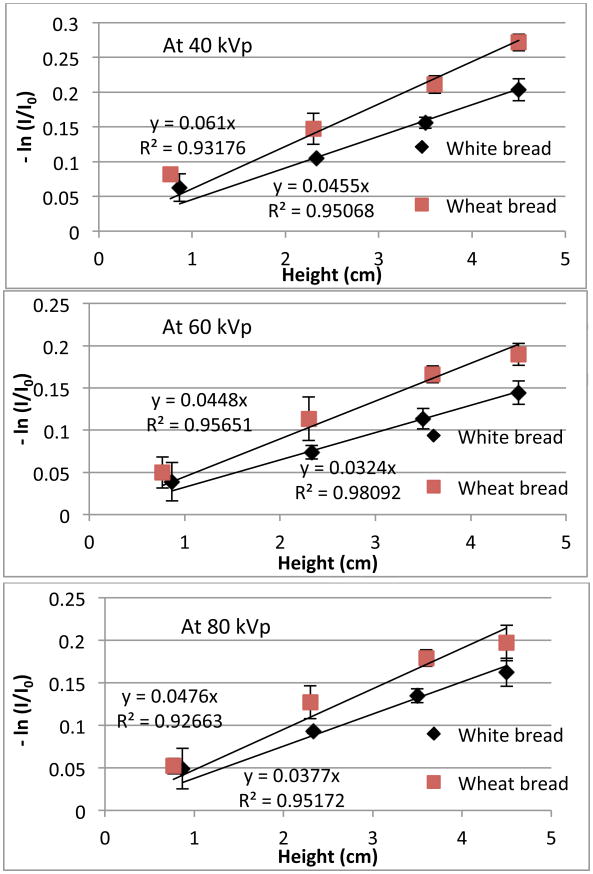

In order to determine the x-ray linear attenuation coefficients (μ) of the food samples, the x-ray intensity (-ln I/I0) was determined from the grayscale values and plotted against the thickness of the sample. Accordingly up to six slices of classic white and whole-wheat bread samples were scanned on the DR and a linear relationship was observed between x-ray intensity (-ln I/I0) and thickness, t (height) verifying the Beer-Lambert's law (Jackson & Hawkes, 1980) at all three x-ray energy levels (Fig. 3). Corresponding slopes representing the linear attenuation coefficient (μ) for the samples were noted and the apparent density was thus determined using equation (7). Table 1 gives comparative analysis of the apparent densities for breads calculated from its x-ray intensity and externally determined using the dimension technique. No significant difference (p < 0.05) in the apparent density values with a percent difference of 10% was observed between determining density using the DR x-ray method and the conventional method. Similar results were obtained using the intercept method to determine density.

Figure 3. Linear attenuation coefficient (μ) of the bread samples obtained as a slope in a plot of x-ray intensity against thickness at 40, 60, and 80 kVp.

Table 1. Apparent densities of food samples using density equation (7) obtained on x-ray radiography (DR) and dimension technique.

| Food item | Apparent densities of bread samples determined using density equation (7) (g/cm3) | Apparent density using dimension techniques (g/cm3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Average | SD | Average | SD | |

| White bread | 0.279a | 0.061 | 0.251a | 0.023 |

| Wheat bread | 0.342a | 0.042 | 0.380a | 0.031 |

Values are means, n=3; Means with different letter in a row differ significantly, p<0.05

4.2 Apparent density using x-ray linear attenuation coefficient on computed tomography (CT)

To validate Beer-Lambert's law, whole wheat bread slices were compressed and a proportional increase in x-ray attenuation was observed in accordance with the law (Table 3). The apparent densities determined using x-ray attenuation for compressed slices were not significantly different (p < 0.05) from that obtained by measuring dimensions of compressed bread for volumes and weight.

Table 3. Increase in x-ray attenuation on compression of bread in accordance with Beer-Lambert's law.

| Whole wheat bread compressed to 1.5cm | Average x-ray attenuation, μ (1/cm) | Apparent density calculated using the density equation (7) (g/cm3) | Apparent density using dimension techniques (g/cm3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| At 45 kVp | At 55 kVp | At 70 kVp | ρ | SD | ρ | SD | |

| 2 slices | 0.206 | 0.171 | 0.142 | 0.357a | 0.018 | 0.307a | 0.035 |

| 4 slices | 0.377 | 0.309 | 0.260 | 0.648a | 0.020 | 0.607a | 0.052 |

| 6 slices | 0.609 | 0.492 | 0.410 | 0.947a | 0.025 | 0.939a | 0.078 |

Values are means, n=3; Means with different letter in a row differ significantly, p<0.05

Food samples were then scanned at three x-ray voltages to obtain their linear attenuation coefficients (μ) were obtained (Table 4). The mean apparent density was then determined for these porous foods using the density equation (7) and compared to apparent density obtained via dimension technique as shown in Table 5. For both the porous foods like breads and cookies; as well as liquid foods such as tomato paste, mayonnaise, and soybean oil, there was no significant difference (p < 0.05) on comparison with conventional measured density using dimension technique or pycnometer. Density determined from linear attenuation coefficients for all foods with mean 0.579 g/cm3 resulted in SD = 0.0367 g/cm3. Similar results were obtained using the intercept method to determine density. This further established the validity of density determination from x-ray linear attenuation coefficients.

Table 4. X-ray linear coefficients (μ) of a CT slice of different food samples at different x-ray tube voltages.

| No | Food item | Average x-ray linear attenuation coefficients (μ), (1/cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| At 45 kVp | At 55 kVp | At 70 kVp | |||||

|

| |||||||

| μ | SD | μ | SD | μ | SD | ||

| 1 | French bread | 0.105 | 0.006 | 0.086 | 0.005 | 0.073 | 0.005 |

| 2 | Rye bread | 0.175 | 0.023 | 0.128 | 0.010 | 0.109 | 0.007 |

| 3 | Multigrain bread | 0.180 | 0.013 | 0.147 | 0.005 | 0.128 | 0.014 |

| 4 | Sponge cake | 0.172 | 0.005 | 0.145 | 0.005 | 0.120 | 0.004 |

| 5 | Cornbread | 0.309 | 0.011l | 0.259 | 0.007 | 0.213 | 0.007 |

| 6 | Sugar cookie | 0.385 | 0.045 | 0.324 | 0.037 | 0.272 | 0.031 |

| 7 | Granola bar | 0.449 | 0.018 | 0.365 | 0.017 | 0.301 | 0.015 |

| 8 | Shortbread cookie | 0.398 | 0.005 | 0.329 | 0.003 | 0.279 | 0.002 |

| 9 | Pop tart | 0.629 | 0.049 | 0.518 | 0.050 | 0.426 | 0.047 |

| 10 | Soybean oil | 0.410 | 0.002 | 0.358 | 0.001 | 0.313 | 0.002 |

| 11 | Mayonnaise | 0.542 | 0.003 | 0.461 | 0.002 | 0.389 | 0.002 |

| 12 | Tomato paste | 0.801 | 0.002 | 0.661 | 0.001 | 0.547 | 0.003 |

Values are means, n= 10; SD indicates the noise present in the CT data

Table 5. Apparent densities (ρ) of porous foods determined using density equation (7) obtained on a CT and dimension or pycnometer technique.

| No | Food item | Apparent density calculated using the density equation (7) (g/cm3) | Apparent density using dimension or pycnometer techniques (g/cm3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| ρ | SD | ρ | SD | ||

| 1 | French bread | 0.159a | 0.036 | 0.124a | 0.010 |

| 2 | Rye bread | 0.258a | 0.028 | 0.224a | 0.039 |

| 3 | Multigrain bread | 0.241a | 0.061 | 0.243a | 0.013 |

| 4 | Sponge cake | 0.277a | 0.043 | 0.343a | 0.063 |

| 5 | Cornbread | 0.457a | 0.064 | 0.439a | 0.057 |

| 6 | Sugar cookie | 0.559a | 0.024 | 0.566a | 0.020 |

| 7 | Granola bar | 0.546a | 0.049 | 0.624a | 0.026 |

| 8 | Shortbread cookie | 0.643a | 0.073 | 0.662a | 0.011 |

| 9 | Pop tart | 0.823a | 0.035 | 0.853a | 0.015 |

| 10 | Soybean oil | 0.959a | 0.020 | 0.925a | 0.001 |

| 11 | Mayonnaise | 0.937a | 0.048 | 0.916a | 0.006 |

| 12 | Tomato paste | 1.085a | 0.012 | 1.095a | 0.007 |

Values are means, n=3; Means with different letter in a row differ significantly, p<0.05

5. Conclusions

X-ray imaging can determine apparent density of a wide variety of food materials accurately. It was demonstrated that apparent density could be directly calculated from x-ray linear attenuation coefficients (μ). Also the study showed the universal applicability of determining density using x-ray linear attenuation coefficients for different x-ray imaging techniques such as digital radiography and computed tomography.

Direct density determination using x-ray mass attenuation coefficient on digital radiography required the knowledge of thickness of sample. However, thickness or any additional information about the food material was not required on the computed tomography. The approach was effectively used to determine apparent density from x-ray linear attenuation coefficients obtained at least two energy levels. This direct density determination technique will be advantageous for rapid density determination of food products. This technique can certainly be applied to a dual-energy CT for faster measurement and improved accuracy. Moreover, it could easily be applied to all kinds and shapes of foods.

Table 2. Average x-ray linear attenuation coefficient μ (1/cm) of a whole granola bar sample.

| Micro CT tube voltages | X-ray linear attenuation coefficient, μ of a whole granola bar sample (1/cm) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Average | SD | |

| 45 k Vp | 0.431 | 0.023 |

| 55 k Vp | 0.360 | 0.019 |

| 70 kVp | 0.299 | 0.016 |

Values are means, n=5

Highlights.

X-ray imaging used to accurately determine apparent density of foods

Apparent density determined directly using x-ray linear attenuation coefficients

Apparent density measured for porous and non-porous foods via x-ray imaging compared within 10% to traditional methods

Acknowledgments

The authors wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Xun Zhou and Mitch Simmonds, Purdue University; Small Animal Clinic, School of Veterinary Sciences, Purdue University; and Pam Lachcik, Technician, Animal Facility, Department of Nutrition Science, Purdue University. Support for this work comes from the National Cancer Institute (1U01CA130784-01) and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disorders (1R01-DK073711-01A1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahuja JKA, Montville JB, Omolewa-Tomobi G, Heendeniya KY, Martin CL, Steinfeldt LC, Anand J, Adler ME, LaComb RP, Moshfegh AJ. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 5.0. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group; Beltsville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists. 10th. The Association; St.Paul, MN, USA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bushberg JT, Seibert JA, Leidholt EM, Boone JM. The Essential Physics of Medical Imaging. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bellido GG, Scanlon MG, Page JH, Hallgrimsson B. The bubble size distribution in wheat flour dough. Food Research International. 2006;39:1058–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Besbes E, Jury V, Monteau JY, Le Bail A. Characterizing the cellular structure of bread crumb and crust as affected by heating rate using X-ray microtomography. Journal of Food Engineering. 2013;115(3):415–423. [Google Scholar]

- Cafarelli B, Spada A, Laverse J, Lampignano V, Del Nobile MA. X-ray microtomography and statistical analysis: Tools to quantitatively classify bread microstructure. Journal of Food Engineering. 2014;124:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cho ZH, Tsai CM, Wilson G. Study of contrast and modulation mechanisms in X-ray/photon transverse axial transmission tomography. Phys Med Biol. 1975;20:879. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/20/6/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkesen I, Kelkar S, Campanella OH, Sumnu G, Sahin S, Okos M. Characterization of structure of gluten-free breads by using X-ray microtomography. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;36:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Frisullo P, Laverse J, Marino R, Nobile MAD. X-ray computed tomography to study processed meat microstructure. Journal of Food Engineering. 2009;94(3-4):283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran S, Paulsen MR, Shove GC. Optical methods for nondestructive quality evaluation of agricultural and biological materials. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research. 1985;32:209–241. [Google Scholar]

- Falcone PM, Baiano A, Zanini F, Mancini L, Tromba G, Dreossi D, Montanari F, Scuor N, Nobile MAD. Three-dimensional Quantitative Analysis of Bread Crumb by X-ray Microtomography. Journal of Food Science. 2005;70:E265–E272. [Google Scholar]

- Haff RP, Toyofuko N. X-ray detection of defects and contaminants in the food industry. Sensing and Instrumentation for Food Quality and Safety. 2008;2:262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Heismann BJ, Leppert J, Stierstorfer K. Density and atomic number measurements with spectral x-ray attenuation method. Journal of Applied Physics. 2003;94(3):2073–2079. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat M, Guthausen G, Tepper P, Falco L, Schuchmann HP. Non-destructive, quantitative characterization of extruded starch-based products by magnetic resonance imaging and X-ray microtomography. Journal of Food Engineering. 2014;124:122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell JH. Bibliography of Photon Total Cross Section (Attenuation Coefficient) Measurements 10 eV to 13.5 GeV. NISTIR 5437 1994:1907–1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hünemohr N, Paganetti H, Greilich S, Jäkel O, Seco J. Tissue decomposition from dual energy CT data for MC based dose calculation in particle therapy. Medical physics. 2014;41(6):061714. doi: 10.1118/1.4875976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DF, Hawkes DJ. X-ray attenuation coefficients of elements and mixtures. Physics Reports. 1981 Apr;70(3):169–233. [Google Scholar]

- Jennes R, Koops J. Preparation and properties of a salt solution which simulates mi Ik ultra filtrate Neth. Milk Dairy J. 1962;16:153. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang JA, Chang HY, Wu KH, Ouyang CS, Yang MM, Yang EC, Chen TW, Lin TT. An adaptive image segmentation algorithm for X-ray quarantine inspection of selected fruits. Computers and electronics in agriculture. 2008;60(2):190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar S, Stella S, Boushey C, Okos M. Developing novel 3d measurement techniques and prediction method for food density determination. Procedia Food Science. 2011;1:483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Schatzki T. Detection of pinholes in almonds through X-ray imaging. Transactions of the ASAE. 2001;44(4):997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Kotwaliwale N, Singh K, Kalne A, Jha SN, Seth N, Kar A. X-ray imaging methods for internal quality evaluation of agricultural produce. Journal of Food Science &Technology. 2011:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0485-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsenin NN. Physical properties of plant and animal materials. G&B Scientific; NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza F, Verboven P, Mebatsion HM, Kerckhofs G. Three-dimensional pore space quantification of apple tissue using X-ray computed microtomography. Planta. 2007;226:559–570. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards & Technology (NIST) http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xraycoef/index.cfm.

- Nicolaï BM, Defraeye T, De Ketelaere B, Herremans E, Hertog ML, Saeys W, Torricelli A, Vandendriessche T, Verboven P. Nondestructive Measurement of Fruit and Vegetable Quality. Annual review of food science and technology. 2014;(0) doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030713-092410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareyt B, Talhaoui F, Kerckhofs G, Brijs K, Goesaert H, Wevers M, Delcour JA. The role of sugar and fat in sugar-snap cookies: Structural and textural properties. Journal of Food Engineering. 2009;90(3):400–408. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DH, Lannutti JJ. Measuring physical density with X-ray computed tomography. NDT & E International. 1997;30(6):339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MS. Food Properties Handbook. CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Seeram E. Digital Radiography: An Introduction for Technologists. Delmar Cengage Learning 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Bortfeld T, Schlegel W. Correlation between CT numbers and tissue parameters needed for Monte Carlo simulations of clinical dose distributions. Physics in medicine and biology. 2000;45(2):459. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/2/314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyck T, Verboven P, Herremans E, Defraeye T, Van Campenhout L, Wevers M, Nicolaï B. Characterization of structural patterns in bread as evaluated by X-ray computer tomography. Journal of Food Engineering. 2014;123:67–77. [Google Scholar]