Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a devastating lung disease characterized by inflammation and the development of excessive extracellular matrix deposition. Currently, there are only limited therapeutic intervenes to offer patients diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis. While previous studies focused on structural cells in promoting fibrosis, our study assessed the contribution of macrophages. Recently, toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling has been identified as a regulator of pulmonary fibrosis. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-M (IRAK-M), a MyD88-dependent inhibitor of TLR signaling, suppresses deleterious inflammation, but may paradoxically promote fibrogenesis. Mice deficient in IRAK-M (IRAK-M−/−) were protected against bleomycin-induced fibrosis and displayed diminished collagen deposition in association with reduced production of interleukin (IL)-13 compared to wild type (WT) control mice. Bone marrow (BM) chimera experiments indicated that IRAK-M expression by BM derived cells, rather than structural cells, promoted fibrosis. After bleomycin, WT macrophages displayed an alternatively activated phenotype, whereas IRAK-M−/− macrophages displayed higher expression of classically activated macrophage markers. Using an in vitro co-culture system, macrophages isolated from in vivo bleomycin-challenged WT, but not IRAK-M−/−, mice promoted increased collagen and α-smooth muscle actin expression from lung fibroblasts in an IL-13-dependent fashion. Finally, IRAK-M expression is upregulated in peripheral blood cells from IPF patients and correlated with markers of alternative macrophage activation. These data indicate expression of IRAK-M skews lung macrophages towards an alternatively activated profibrotic phenotype, which promotes collagen production leading to the progression of experimental pulmonary fibrosis.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive interstitial pneumonia characterized by lung injury and inflammation, fibroblast hyperplasia, deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) and scar formation resulting in a median survival of 2–5 years after diagnosis (1). Although no current animal model recapitulates all of the clinical manifestations of fibrosis, we and others have employed a bleomycin model to identify pathologic cells and profibrotic mediators important in disease progression (2). This well characterized model has clinical relevance and has been used to identify pathologic cells and profibrotic mediators important in human disease.

A number of host derived soluble mediators have been shown to promote lung fibroproliferation in IPF patients. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a pleotropic mediator which has been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of IPF; however, the mechanism and activation of this important signaling mediator has yet to be fully elucidated. Interleukin (IL)-13 is another important soluble mediator that has been implicated in the development and progression of pulmonary fibrosis. While originally described as a molecule primarily expressed by activated T cells (3), IL-13 is produced by a variety of cell types, including fibroblasts and macrophages. Mice deficient in IL-13 are protected from experimentally-induced fibrosis (4) and IL-13 producing cells are required for the maintenance of fibrosis (5). Increased quantities of IL-13 have been detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of IPF patients (6). Additionally, alveolar macrophages from IPF patients produce elevated levels of IL-13 and expression of both IL-13 and one of its receptors, IL-13Rα1, correlate with disease severity (7). IL-13 promotes fibrosis by regulating the gene expression of profibrotic molecules, such as pro-collagen IIIA and is a potent inducer and activator of TGF-β (8).

Macrophages phagocytize debris, modulate inflammatory responses, and promote fibroproliferation. Importantly, macrophages that are alternatively rather than classically activated exert profibrotic effects, and increased expression of these markers (such as arginase 1, YM1/2 and Fizz1) have been found in IPF patients (9–11). Macrophages can be skewed towards an alternatively activated phenotype in the presence of IL-4; however, other work has shown that IL-13 can also drive this phenotypic switch. Incubation of human lung fibroblasts with conditioned media from IPF macrophages induces procollagen expression from fibroblasts (12) demonstrating regulation of ECM deposition by alternatively activated macrophages.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize evolutionarily conserved motifs important in inflammation and immunity. Although originally defined as pathogen recognition receptors, TLRs also recognize endogenously produced molecules (13). Recent work has begun to address the role of TLRs in pulmonary fibrosis. The combined absence of both TLR2 and TLR4 increased susceptibility to bleomycin and radiation induced pulmonary fibrosis (14, 15). Moreover, MyD88−/− mice are more susceptible to pulmonary fibrosis, as compared to WT mice (16). Conversely, TLR2 was found to be elevated in IPF patients (17) and the pharmacologic inhibition of TLR2 protected mice against bleomycin challenge (18). Interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase-M (IRAK-M or IRAK-3) is a negative regulator of MyD88-dependent TLR signaling. Originally described in monocytes and macrophages, IRAK-M has also been found in epithelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts (19–21). Expression of IRAK-M is upregulated by pro-fibrotic molecules, such as IL-13 (22) and TGF-β (23). Additionally, this molecule has been shown to suppress deleterious inflammation in influenza-induced lung injury but mediates impaired antibacterial immunity in the setting of experimental sepsis (24, 25). Recently, our lab has shown that IRAK-M−/− mice are protected from hyperoxic lung injury (26) and the absence of IRAK-M skews tumor associated macrophages towards classical rather than alternative activation (23). However, the role of IRAK-M in regulating macrophage activation in lung fibroproliferative responses has not been examined. Our data shows that IRAK-M promotes alternative macrophage activation in the setting of bleomycin-induced lung injury, which drives lung fibrogenesis in an IL-13-dependent fashion.

Material and Methods

Animals

A colony of IRAK-M−/− (deficient) mice bred on a B6 background for more than ten backcrosses was established at the University of Michigan (24). Age- and sex-matched specific pathogen-free 6- to 8-wk-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions within the University of Michigan Animal Care Facility (Ann Arbor, MI). All animal experiments preceded in accordance with National Institutes of Health policies on the human care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) at the University of Michigan.

Bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis and histology

WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were injected with bleomycin (0.025 U; Sigma) intratracheally (i.t.) on day 0. Lungs were collected on days 0, 7, 14, and 21 to measure cytokine protein expression by ELISA and mRNA expression by realtime RT-PCR and on day 14 and 21 for histology and determination of collagen content by hydroxyproline assay (27). For histology samples, lungs were perfused with saline and inflated with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Sections were stained with hematosylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

Mice were euthanized and BAL was performed as previously described (28). Lavaged cells from each group of animals were pooled and cytospins (Thermo Electron Corp. Waltham, MA) were prepared for determination of BAL differentials using a modified Wright-Giemsa stain.

ELISA

The concentration of albumin was determined via mouse albumin ELISA quantification kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). The amount of cytokines and chemokines in the BAL, lung homogenates and lung macrophages was determined via DouSet ELISA (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). Specifically, the amount of TGF-β production was measured in acid activated supernatants to measure total active TGF-β.

Isolation of macrophages

Macrophages were isolated from the whole lungs of mice via a collagenase digestion as previously described (24). Cells were adherence purified for 1 hr in serum free media, non-adherent cells (such as lymphocytes) were washed away and complete media was replaced for overnight incubation. After overnight incubation, macrophage purity was >95% as determined by modified Wright-Giemsa stain. Bone marrow cells were isolated from the femurs of WT and IRAK-M−/− mice and differentiated in to mature macrophages in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 IU/mL Penicillin and 50 µg/mL Streptomycin and 20 ng/mL recombinant mouse M-CSF added on day 1 and 4. Cells were allowed to differentiate up to 7 days in total. Macrophages were stimulated over night with either rmIL-13 (10 ng/ml) and/or rmIL-13 and rmIL-4 (10 ng/ml) (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Murine alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) isolation and cell culture conditions

Murine type II AECs were isolated using the method developed by Corti et al. (29). Briefly, the pulmonary vasculature was perfused and the lungs were filled with 1 ml of dispase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), then 1 ml of low melting point agarose and finally placed in ice cold PBS to harden. The lungs were then submerged in dispase for 45 min before the being minced and incubated in DMEM with 0.01% DNase for 10 min. A single cell suspension was obtained by passing the lung mince over a series of nylon filters. Myeloid cells were removed by first incubating cells with biotinylated antibodies against CD32 and CD45 (BD Pharmingen, San Deigo, CA) then streptavidein-coated microbeads (Promega, Madison, WI), and performing a negative selection using a magnetic tube separator. Mesenchymal cells were removed by overnight adherence in a Petri dish and the resulting nonadherent AECs were either assayed immediately (ex vivo AECs), plated on fibronectin coated dishes for designated time periods. Previous work has shown that the day 3 time point has >90% pure AECs (29).

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

WT and IRAK-M−/− mice received 13 Gy of total body irradiation (TBI) (137Cs source) delivered in two fractions separated by 3 h. Bone marrow (BM) was harvested from the femur of donor mice and BM was transplanted into the lethally irradiated recipients via tail vein infusion. All experiments with BMT mice were performed 6–8 weeks post-BMT, as previously described (30).

Semi-quantitative real time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7000 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed and previously described (26). Gene-specific primers and probes were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Western blotting

Lung macrophages were lysed in buffer containing RIPA (Sigma) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) and gels were subjected to electrophoresis as previously described (26). Membranes were and incubated with antibodies against IRAK-M (Abcam; 1:1000), total-STAT6 (cell signaling,1:500), phosphor-STAT6 (Abcam, 1:500) or β-actin (Abcam, 1:10, 000). Signals were developed with an ECL Plus Western blot detection kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Densitometry was calculated using Image J.

Macrophage or macrophage supernatant and fibroblast co-culture

Fibroblasts were isolated from WT unchallenged mice as previously described (4). After 14 days in culture, lung fibroblasts were removed, counted and plated at 5 × 105 cells per well and serum starved overnight. Lung leukocytes were isolated from either unchallenged or day 14 bleomycin challenged WT and IRAK-M−/− mice. CD45+ cells were isolated from the total lung leukocytes by SuperMacs column (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). Total cells were enumerated by hemocytometer and percent of macrophages were determined modified Wright Gimesa stain. Approximately 1 × 106 macrophages were incubated with the adherent serum starved fibroblasts for 1 hour before removing all non-adherent cells (such as lymphocytes) and adding complete media. The percentage of macrophages after adherence purification was >95% as determined by histological staining. Additionally, supernatants were isolated from approximately 1 × 106 macrophages and spun down to remove all cellular debris before being added to WT fibroblasts cultures. Finally, either control IgG or anti-IL-13 neutralizing antibody (2 µg/ml, provided by Steven Kunkel, University of Michigan) was added to the co-culture systems. Co-cultures were then incubated at 37°C for 48h before isolating mRNA by trizol extraction.

Gene profiling for peripheral blood RNA of IPF and healthy subjects

The data presented in this study were generated using a search of the GEO Profiles database (data accessible at NCBI GEO database GSE33566 (31)). Peripheral blood gene expression data (collected in PAXgene RNA tubes, PreAnalytiX, 762164 Qiagen) from 93 IPF samples and 30 healthy normal controls were analyzed. IPF subjects had a consensus diagnosis of probable or definite IPF based on the ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT criteria and pulmonary function measurements, DLCO or FVC (31). Subjects were excluded from selection if they were current smokers, or currently treated with agents that could alter mRNA levels such as glucocorticoids, azathioprine, or other immunomodulators. Data were normalized in Expression Console (Affymetrix, Inc, Santa Clara, CA) using RMA method. Two sample t tests were used to compare the difference in gene expression levels in peripheral blood RNA between IPF patients and healthy donors. The correlation between IRAK-M and arginase was assessed by Person correlation method.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed using Prism 5.0 statistical program (GraphPad Software). Comparisons between two experimental groups were performed with Student's t-test. Comparisons among three or more experimental groups were performed with ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test to determine significance. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

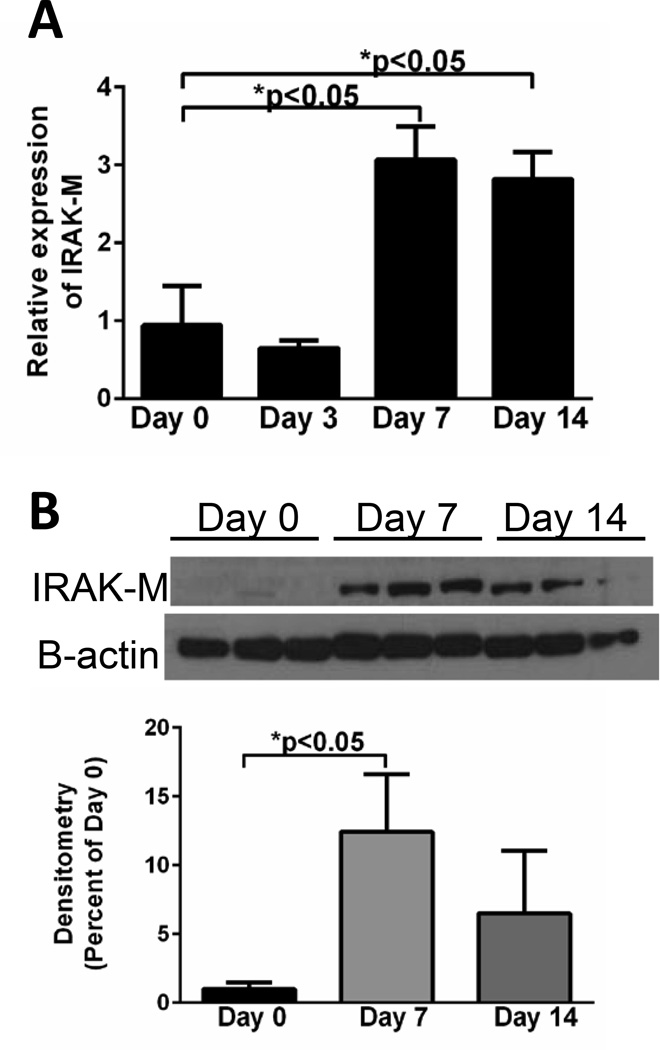

Bleomycin induces expression of IRAK-M in lung macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells

To determine whether IRAK-M expression was upregulated during experimental fibrosis, mRNA and protein expression of IRAK-M was measured in isolated lung cells after bleomycin challenge. There was a marked time-dependent increase in the expression of IRAK-M mRNA (Figure 1A) and protein (Figure 1B) beginning at 7 days (>12-fold increase in protein) after bleomycin challenge and continuing through day 14 day in pulmonary macrophages isolated from dispersed lung. We also observed an early increase in the expression of IRAK-M mRNA in AECs isolated from bleomycin challenged mice at day 3 (maximal 4.5-fold increase), before returning to baseline by day 7 (Supplemental Figure 1A). No induction of IRAK-M was noted in lung fibroblasts isolated from bleomycin treated mice at any time points post challenge (Supplemental Figure 1B). These data demonstrated a substantial induction of IRAK-M expression in lung macrophages and to a lesser extent AECs post-bleomycin administration.

Figure 1. IRAK-M expression in macrophages is elevated after bleomycin challenge.

WT mice were given an i.t challenge with bleomycin and lung macrophages were isolated. The amount of IRAK-M expression was measured by realtime RT-PCR (A) and western blot analysis and densitometry (B). Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=3 samples/group from 2 separate experiments. Unless otherwise noted *p<0.05 when compared to day 0 sample.

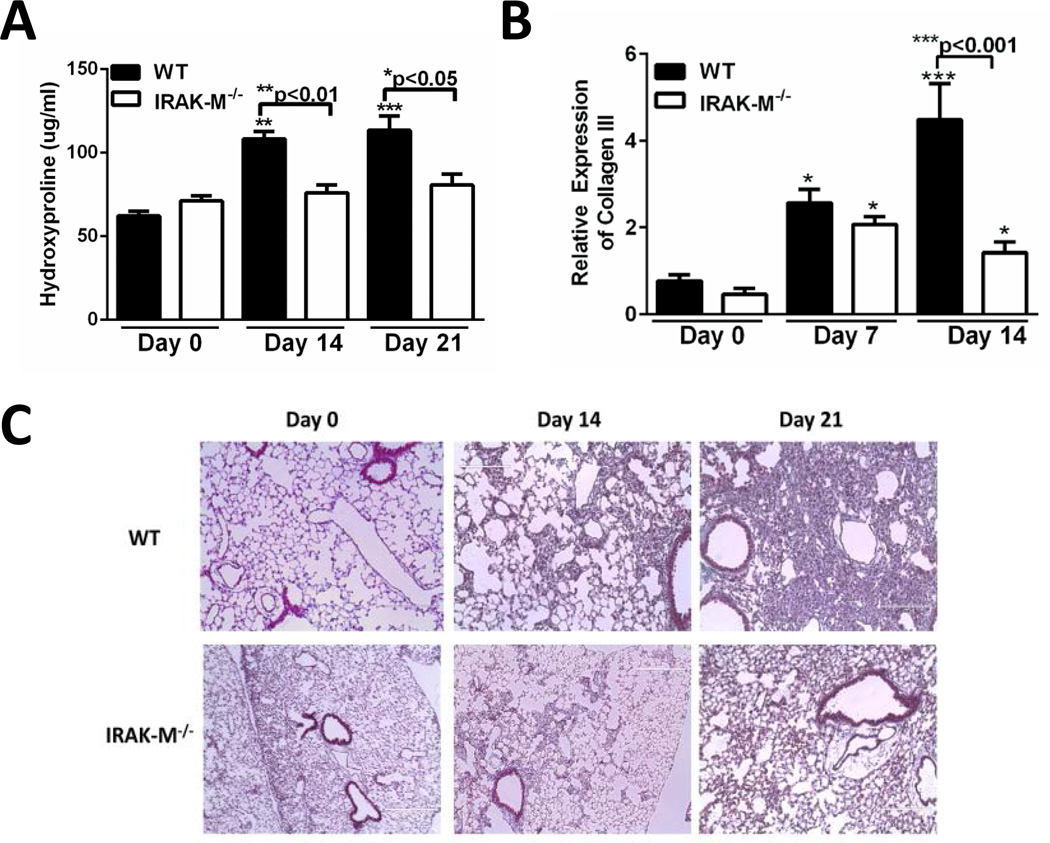

IRAK-M regulates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis

Modulation of IRAK-M expression has previously correlated with altered susceptibility to injury and infection (24–26); however the role of this negative TLR regulator in pulmonary fibrosis has yet to be explored. To determine whether IRAK-M was critical for the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were challenged with bleomycin and the amount of fibrosis was measured. To quantitate fibrosis, whole lungs were harvested from WT and IRAK-M−/− at day 14 and 21 post-bleomycin and the amount of collagen was measured by hydroxyproline assay. As compared to unchallenged control mice, WT mice had significantly higher collagen deposition at day 14 and 21 post-bleomycin challenge. In contrast, there was no significant increase in collagen deposition in whole lungs from IRAK-M−/− mice after bleomycin administration (Figure 2A). We also observed substantially greater induction of collagen III mRNA in whole lung samples from WT mice at 14 days post bleomycin (4.5-fold increase compared to 1.4-fold increase) as compared to IRAK-M−/− mice (Figure 2B). Finally, increased collagen deposition as shown by enhanced trichrome staining was observed at both day 14 and day 21 in the WT mice challenged with bleomycin. By comparison, there was a relatively modest increase in collagen deposition and preserved lung architecture in IRAK-M−/− mice after administration of bleomycin (Figure 2C). These data show that IRAK-M−/− mice were protected from bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, indicating that IRAK-M is a key mediator of fibrogenesis in response to bleomycin.

Figure 2. Expression of IRAK-M regulates bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis.

WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were given an i.t challenge with bleomycin and whole lungs were isolated at either day 0, 14, or 21 and amount of collagen was assessed by hypdroxyproline assay (A), mRNA expression of collagen III in whole lungs (B) or trichrome staining of histological sections (C). Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=4 samples/group from 2 separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 when compared to day 0 WT control sample

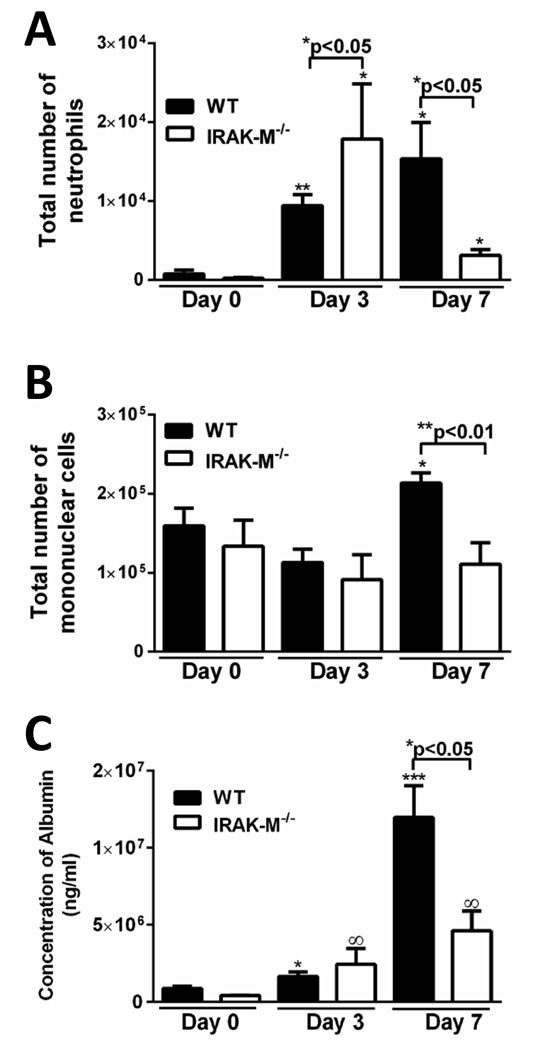

Alterations in leukocyte influx and alveolar permeability in IRAK-M−/− mice after bleomycin challenge

To determine whether IRAK-M regulated inflammatory cell recruitment after bleomycin challenge, the total number and subtype of leukocytes were enumerated from whole lung digestion. Administration of bleomycin to WT mice resulted in an increase in lung neutrophils at both 3 and 7 days post treatment (Figure 3A). As compared to WT mice, there was a significant increase in neutrophils in IRAK-M deficient mice at 3 days post challenge with bleomycin, whereas by 7 days neutrophil numbers were less than that observed in WT controls (Figure 3A). Conversely, an increase in lung macrophages was not observed until 7 days post bleomycin in WT mice, while no significant increase was noted in IRAK-M−/− mice at either 3 or 7 days (Figure 3B). However, we observed no difference in the production of chemokines, including CXCL1/KC, CXCL2/MIP-2α, or CCL2/MCP-1, or GM-CSF between WT and IRAK-M−/− mice after bleomycin challenge (data not shown).

Figure 3. IRAK-M reduces alveolar permeability and cellular recruitment after bleomycin challenge.

WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were given an i.t. challenge with bleomycin. A. and B. BAL were performed on WT and IRAK-M−/− mice at day 0, 3 and 7 after bleomycin challenge and the total numbers of neutrophils or mononuclear cells were quantified. C. The amount of albumin in the BALF was quantified as a surrogate for the amount of lung leakage after bleomycin challenge. Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=3 samples/group from 3 separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 when compared to day 0 WT control sample and ∞p<0.05 when compared to day 0 IRAK-M−/− control sample.

To determine whether IRAK-M expression regulated lung permeability after bleomycin challenge, the amount of albumin in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was measured as a surrogate for alveolar permeability. In WT mice, treatment with bleomycin resulted in a time-dependent increase in BAL albumin, maximum 7 days post bleomycin (Figure 3C). Interestingly, albumin levels were significantly less in IRAK-M−/− mice 14 days post bleomycin challenge as compared to their WT counterparts.

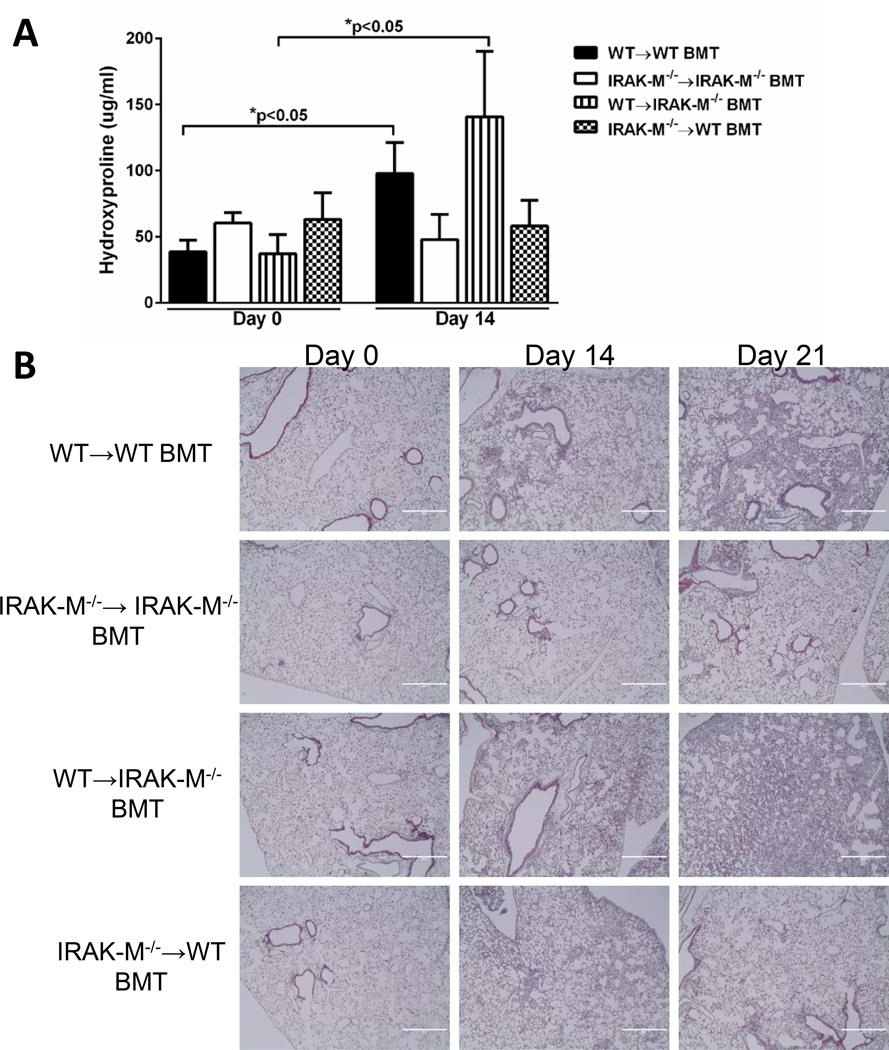

IRAK-M expression by bone marrow cells rather than structural cells enhance susceptibility to bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis

The relative contribution of IRAK-M expression in structural cells and bone marrow derived cells after bleomycin-induced lung injury was delineated by generating bone marrow chimeras. Bone marrow was harvested from WT or IRAK-M−/− mice and transplanted into either IRAK-M−/− or WT lethally irradiated recipients as described in the material and methods section. Five weeks post reconstitution of bone marrow cells, mice were administered an i.t. challenge with bleomycin. Whole lung was collected from either unchallenged or bleomycin challenged mice at day 14 or 21 and the amount of fibrosis was determined by hydroxyproline assay and trichrome staining of histological samples. In bleomycin-challenged animals, there was a significant increase in the amount of hydroxyproline in the WT→WT group (2.5-fold increase) and the WT→IRAK-M−/− group (2.21-fold increase) (Figure 4A). As anticipated, we observed no increase in hydroxyproline levels in the control IRAK-M−/−→IRAK-M−/− after bleomycin challenge. Interestingly, when IRAK-M was absent in the bone marrow compartment (IRAK-M−/−→WT group), there was also no increase in hydroxyproline levels (Figure 4A). To confirm these results, whole lung histology slides were stained with trichrome blue to visualize collagen deposition after bleomycin administration. Again, there was an abundance of trichrome staining in the WT→WT and WT→IRAK-M−/− groups at day 21 post-bleomycin and considerably less in both the IRAK-M−/−→IRAK-M−/− and IRAK-M−/−→WT groups (Figure 4B). These data indicate that the presence of IRAK-M in the bone marrow compartment, rather than the structural cells, mediated the enhanced susceptibility to bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis.

Figure 4. IRAK-M expression in the bone marrow compartment enhances susceptibility to collagen deposition after bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis.

BM chimeras were generated by transplanting WT or IRAK-M−/− BM into lethally irradiated WT or IRAK-M−/− mice. After complete BM reconstitution, mice were given an i.t. challenge with bleomycin and whole lungs were collected at day 0, 14, or 21 post-challenge. The amount of collagen was measured by hydroxyproline assay (A) as well as trichrome staining (B) of histological sections. Graphs represent mean ± SEM n=4 samples/group from 2 separate experiments. *p<0.05 compared to day 0 WT→WT BMT mice.

Increased production of profibrotic molecules in WT but not IRAK-M−/− mice after bleomycin challenge

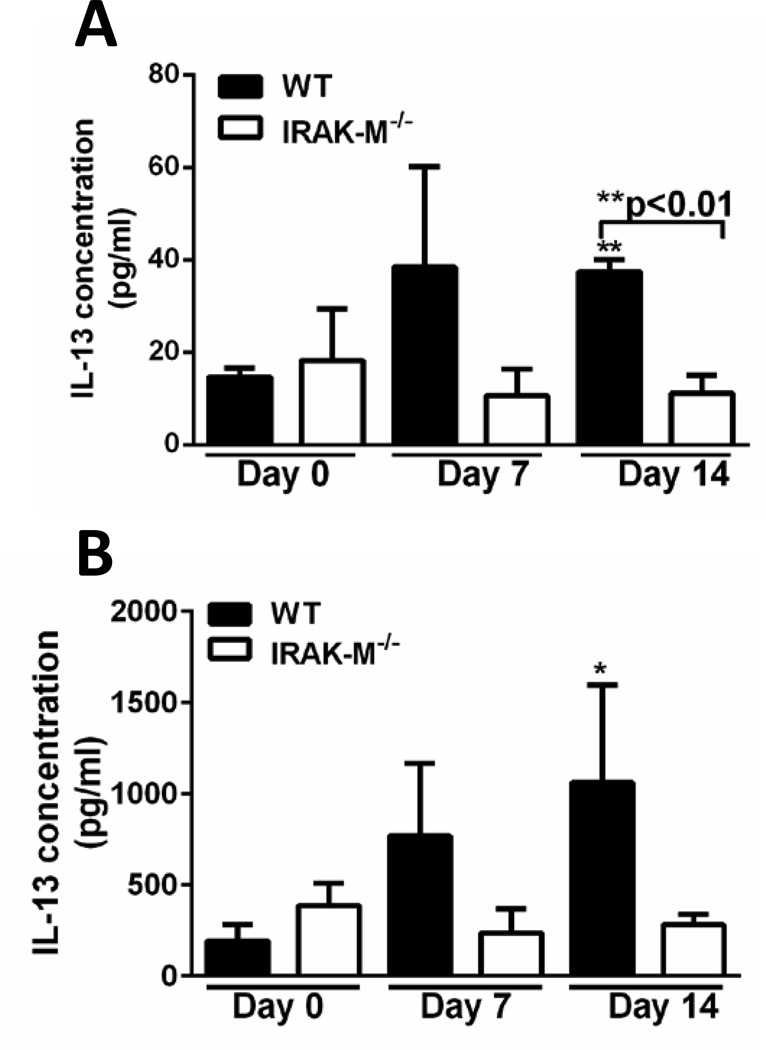

It has previously been shown that cellular mediators play an important role in regulating the development and progression of lung fibrosis. We next assessed the expression of both pro- and anti-fibrotic molecules in whole lung or BALF samples obtained from WT and IRAK-M−/− mice after in vivo bleomycin challenge. Measurement of TGF-β using a luciferase activity assay revealed no differences in the amount of active TGF-β in BALF or whole lung samples isolated from WT and IRAK-M−/− mice (data not shown). Moreover, TNF-α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF were also measured and there was no quantitative difference detected between groups (data not shown). Conversely, there was a significant increase in the production of IL-13 in BALF from WT, but not IRAK-M−/− mice after bleomycin challenge (Figure 5A). To determine whether lung macrophages were producing IL-13 in our model, these cells were isolated by collagenase digestion from whole lungs of WT and IRAK-M−/− mice after bleomycin challenge. There was an increase in the production of IL-13 in WT but not IRAK-M−/− macrophages after induction of fibrosis (Figure 5B). These data indicate that IRAK-M is required for the production of IL-13 after bleomycin challenge.

Figure 5. Expression of IRAK-M enhanced production of IL-13 after bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis.

WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were given an i.t. challenge with bleomycin. Production of IL-13 was measured by ELISA in the BALF (A) or from macrophages supernatants (B) after bleomycin challenge. Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=4 samples/group from 2 separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 when compared to day 0 WT control sample.

IRAK-M skews macrophages towards an alternatively activated phenotype after bleomycin administration

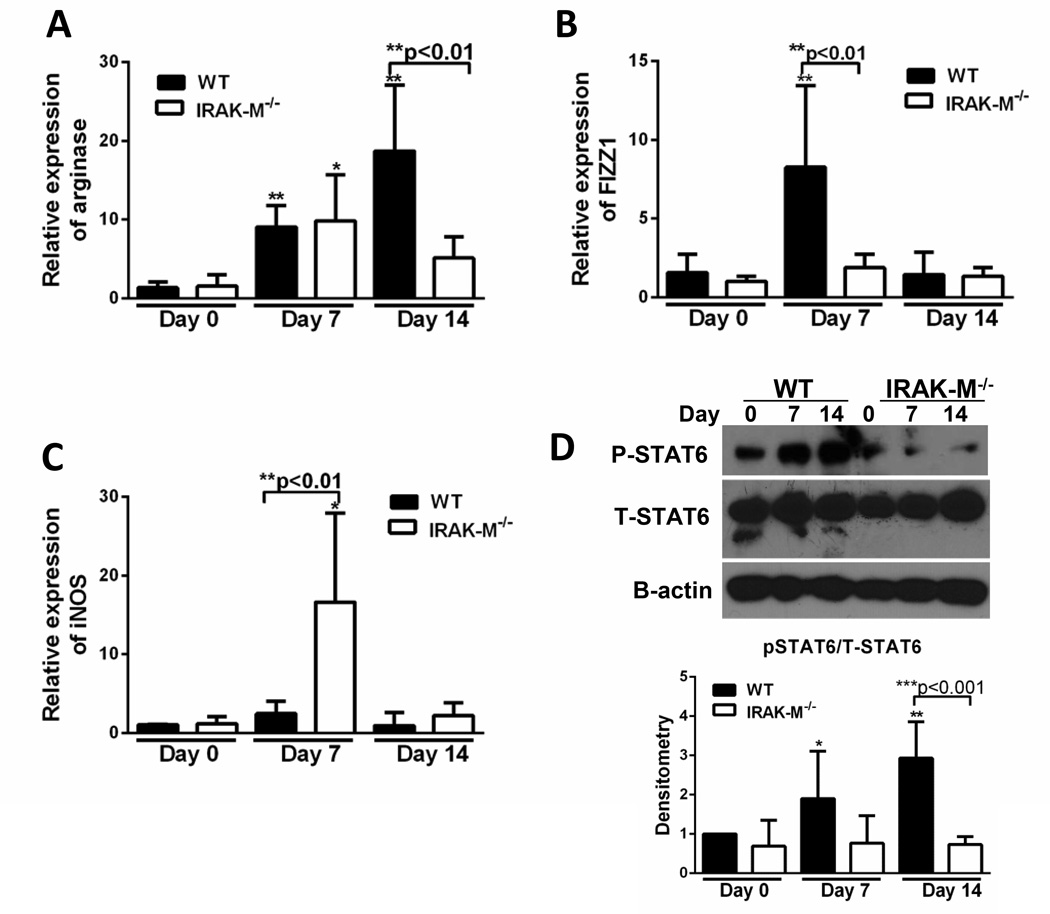

Macrophage activation phenotypes are shaped by microenvironment factors, including cytokines. To determine whether increased production of IL-13 from macrophages corresponded to an alternatively activated macrophage phenotype, we assessed macrophage activation after bleomycin challenge. Lung macrophages were isolated from WT and IRAK-M−/− mice and the expression of classically (iNOS) and alternatively activated (arginase, Fizz1) macrophage markers were determined by realtime RT-PCR. There was a significant increase in the expression of arginase (9-fold increase at day 7 and 18-fold increase at day 14, Figure 6A) and Fizz1 (8.2-fold increased at day 7, Figure 6B) in WT, but not IRAK-M−/−, lung macrophages. Conversely, there was a significant increase in the expression of iNOS in IRAK-M−/−, but not WT, lung macrophages at day 7 (16.6-fold increase at day 7, Figure 6C). Activation of STAT6, an important transcription factor driving alternative activation in macrophages, was measured post-bleomycin. There was a significant increase in the p-STAT6 relative to total STAT6 (and normalized to β-actin expression) in the WT, but not the IRAK-M−/−, lung macrophages after bleomycin challenge (Figure 6D). No difference was noted in the expression of p-STAT1 compared to total STAT1 in these lung macrophage samples (data not shown). These data show that the absence of IRAK-M prevents the skewing of lung macrophages towards an alternatively activated phenotype.

Figure 6. Presence of IRAK-M enhanced alternative activation phenotype after bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis.

WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were given an i.t. challenge with bleomycin and lung macrophages were isolated on the given day. The expression of alternatively activated markers (A and B) and classically activated markers (C) were assessed by realtime RT-PCR. In addition, expression of p-STAT6 and total-STAT6 were measured by western blot analysis and the densitometry was graphed (D). Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=3 samples/group from 3 separate experiments. Unless otherwise noted *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 when compared to day 0 WT control sample.

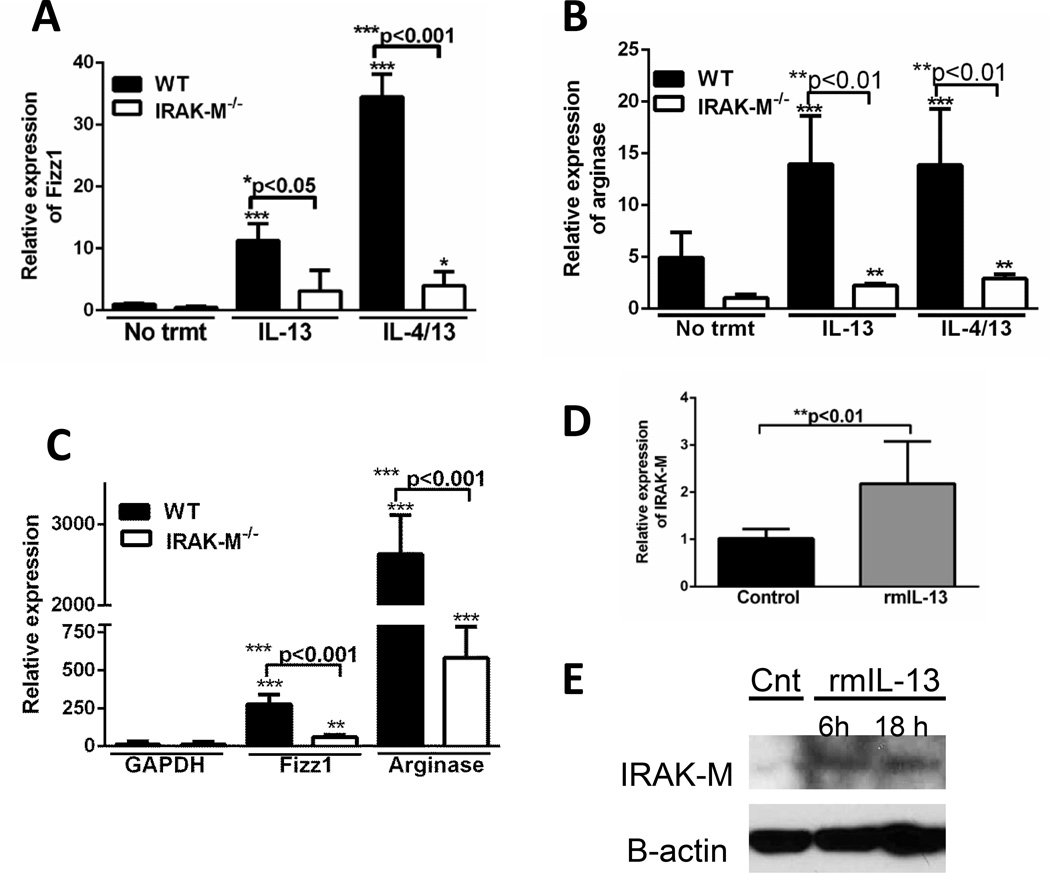

To further define the role of IRAK-M in alternative macrophage activation, lung macrophages and isolated bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) from WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were treated with either rmIL-13 alone or rmIL-4 and rmIL-13 in combination for 24 hours, then expression of macrophage activation markers were measured. A significant increase in the expression of Fizz1 (11.3-fold increase after IL-13 and 34.5-fold increased after IL-4/IL-13, Figure 7A) and arginase 14-fold increase after IL-13 and 13.6-fold increase after IL-4/IL-13, Figure 7B) was detected in WT, but not IRAK-M−/− lung macrophages after incubation with either rmIL-13 alone or in combination with rmIL-4. This effect was not specific for lung macrophages, as BMDM from WT mice showed substantially greater expression of Fizz1 and arginase after treatment with IL-13, as compared to IRAK-M−/− BMDM (Figure 7C). BMDM were highly responsive to IL-13 treatment with 2630-fold increase in Fizz1 expression (Figure 7C) and a 275-fold increase in arginase expression (Figure 7D) compared to untreated controls. Additionally, incubation with exogenous rmIL-13 induced a significant increase in IRAK-M mRNA expression (2.2-fold increase, Figure 7D) and protein expression (Figure 7E) in lung macrophages. These data indicate that IRAK-M promotes IL-4/IL-13-mediated skewing of lung macrophages towards an alternatively activated phenotype, and IL-13 produced by alternatively activated macrophages can reciprocally induce IRAK-M.

Figure 7. Absence of IRAK-M prevented macrophages from skewing towards an alternatively activated phenotype.

Macrophages were isolated from unchallenged WT and IRAK-M−/− mice. Lung macrophages (A and B) were incubated alone, with IL-13 (10 ng/ml) alone or in combination with IL-4 (10 ng/ml) overnight. C. BMDM were isolated from the femurs of WT or IRAK-M−/− mice and cultured in the presence of M-CSF for 7 days. The cells were then counted and incubated with IL-13 (10 ng/ml) overnight. Total mRNA was isolated by trizol extraction and the amounts of alternatively activated markers (A–C) were assessed by realtime RT-PCR. D. and E. Cells were incubated in the presence of exogenous IL-13 (10 ng/ml) for the time indicated before assessing the expression of IRAK-M by realtime-PCR (D) and western blot analysis (E). Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=6 samples/group from 2 separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 when compared to unchallenged WT control samples.

Alternatively activated macrophages increase expression of pro-fibrotic molecules from fibroblasts

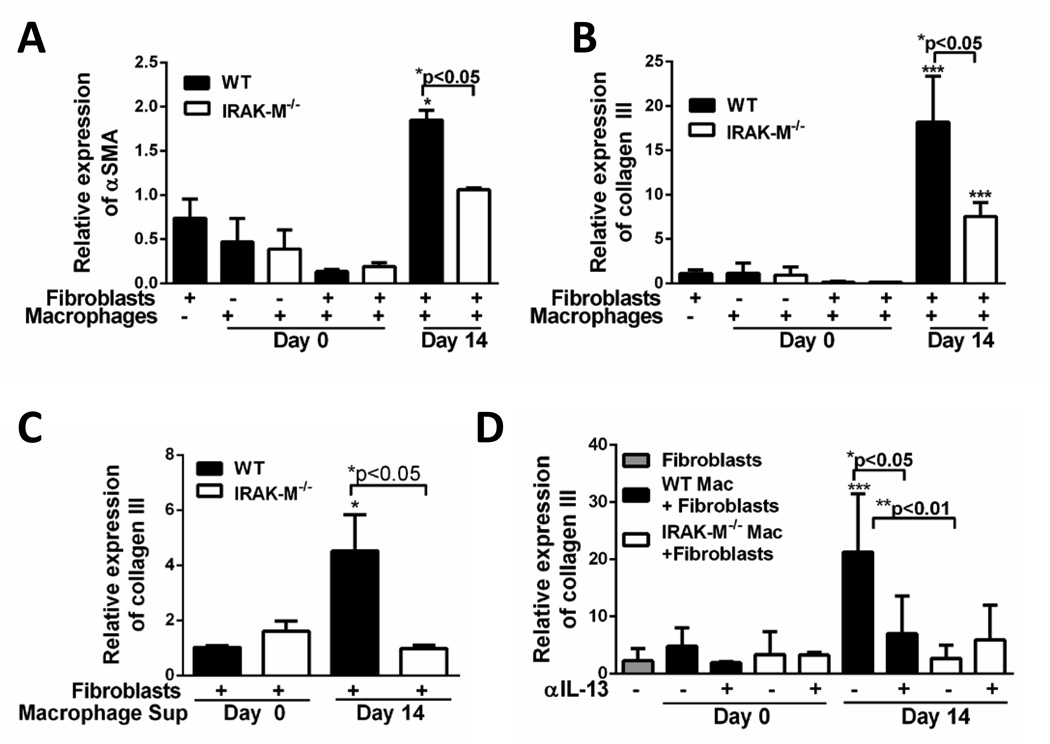

To assess the effect of macrophages on fibroblast effector functions, an in vitro co-culture system was established. First, fibroblasts grown from the lungs of unchallenged WT mice were serum starved for 24 hours. Lung macrophages isolated (as described in the material and methods section) from both unchallenged and day 14 post-bleomycin-challenged WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were incubated either alone or in co-culture with primary resting lung fibroblasts obtained from WT mice. There was no difference in the expression of α-SMA (Figure 8A) or collagen III (Figure 8B) in day 0 macrophages cultured alone or with fibroblasts. However, when macrophages isolated from day 14 challenged WT and IRAK-M−/− mice were co-cultured with lung fibroblasts, there was a significant increase in the expression pro-fibrotic molecules (Figure8A and 8B). Importantly, lung macrophages from WT mice co-cultured with fibroblasts elicited a significantly higher expression (1.9-fold increase αSMA and 18.1-fold increase in collagen III) of pro-fibrotic markers compared to IRAK-M−/− lung macrophages co-cultured with fibroblasts. Furthermore, we measured the amount of active TGF-β in the supernatants from co-cultures experiments and found no differences in the production of TGF-β between co-cultures utilizing IRAK-M−/− macrophages as compared to WT macrophages (data not shown).

Figure 8. Macrophages harvested from bleomycin challenged mice can regulate the profibrotic effector functions of fibroblasts.

Fibroblasts were cultured from previously unchallenged WT mice. Lung macrophages were collected from WT and IRAK-M−/− mice that were either unchallenged or day 14 post-bleomycin challenge. CD45+ cells were isolated from lung macrophages and total numbers of macrophages were quantified by modified Wright-giemsa stain. A. and B. Approximately 1 × 106 total macrophages were co-cultured with 5 × 105 WT fibroblasts. The expression of αSMA (A) and collagen III (B) were measured by realtime RT-PCR. C. Cell free supernatants were harvested from macrophages isolated from bleomycin challenged and cultured with WT unchallenged fibroblasts. The expression of collagen III was measure by realtime RT-PCR. D. Lung macrophages from unchallenged or bleomycin challenged mice were incubated with either control IgG or anti-IL-13 neutralizing antibody (2 µg/ml). The expression of pro-fibrotic mediators were measured after 48 h in culture by realtime RT-PCR (D). Graphs represent mean ± SEM with n=4 samples/group from 2 separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 when compared to fibroblasts from WT unchallenged mice.

To confirm that IRAK-M does not directly regulate lung fibroblast effector responses, primary fibroblasts were isolated from the lungs of WT or IRAK-M−/− mice and treated with TGF-β in vitro and the expression of collagen I and IRAK-M was measured by Western blotting. TGF-β induced a significant increase in the amount of collagen I in fibroblasts from both WT and IRAK-M−/− mice; however there was no IRAK-M expression in unstimulated or stimulated cells (Supplemental Figure 2). To determine whether cell to cell contact was important in regulating collagen production by fibroblasts, macrophage conditioned media was collected from either unchallenged or day 14 bleomycin-challenged WT or IRAK-M−/− lung macrophages and cultured resting fibroblasts. Incubation of supernatants from WT or IRAK-M−/− untreated macrophages did not cause changes in collagen expression; however, supernatants isolated from day 14 bleomycin- challenged WT, but not IRAK-M−/−, macrophages resulted in a significant increase in collagen III expression (Figure 8C).

Previous work has shown that lung macrophages produced IL-13 during experimental fibrosis (4). To further elucidate the mechanism by which macrophages regulate fibroblast effector functions and expression of pro-fibrotic mediators, IL-13 neutralizing or IgG control antibodies were added to the macrophage-fibroblast co-cultures. Again, there was no induction collagen expression in lung fibroblasts co-cultured with resting WT or IRAK-M−/− macrophages (Figure 8D). Similarly, after bleomycin challenge there was a significant increase in the expression of collagen III from WT, but not IRAK-M−/−, macrophage/fibroblast co-cultures. Interestingly, neutralization of IL-13 significantly reduced the expression of collagen III in the day 14 WT macrophage co-culture system; whereas there was no induction in that expressed by the day 14 IRAK-M−/− macrophage/fibroblast co-cultures (Figure 8D). These data suggest that IL-13 produced by WT, but not IRAK-M−/− macrophages after bleomycin challenge stimulated collagen expression from fibroblasts.

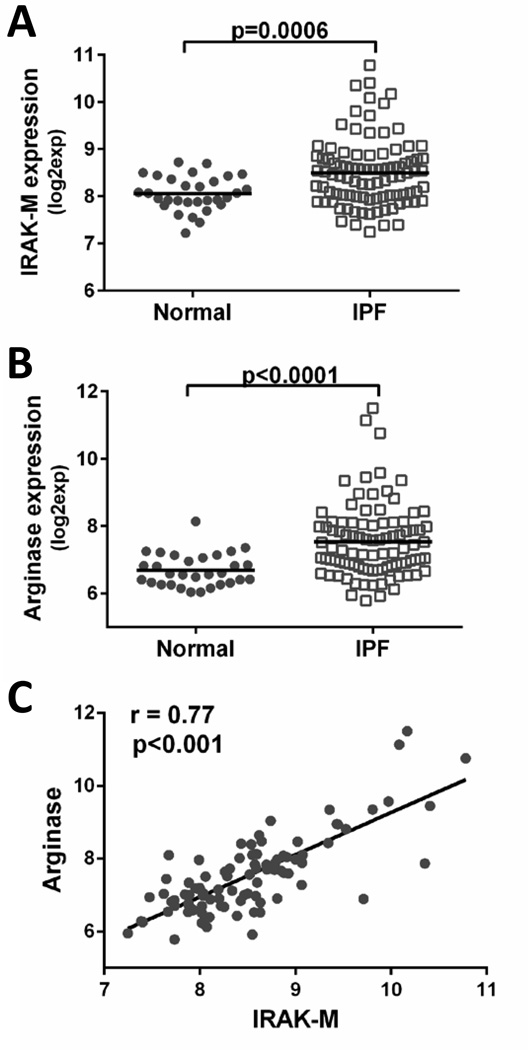

Increased IRAK-M and arginase expression in whole blood cells isolated from IPF patients

To determine whether IRAK-M and the alternative activation marker arginase were differentially expressed in leukocytes isolated from the whole blood of patients with pulmonary fibrosis, gene expression was measured using a GEO database from a previously published peripheral blood transcriptome from 30 normal healthy patients and 93 IPF patients (31). In this study, RNA was isolated from peripheral blood cells from normal healthy controls and IPF patients. The IPF patitents had a consensus diagnosis of probable or definite IPF based on ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT criteria and two pulmonary function measurements (DLCO ≤ 65% and/or FVC≤75%). These data revealed significantly higher expression of IRAK-M in peripheral blood cells from IPF patients as compared to healthy controls (Figure 9A). Conflicting reports regarding the expression of arginase and other alternatively activated macrophage markers in IPF patients have been published (10, 11). To determine whether differences in macrophage activation markers were present in our cohort, we measured gene expression of arginase in peripheral blood cells from IPF or normal healthy control subjects. There was significantly elevated arginase expression from peripheral blood isolated from IPF patients compared to healthy controls (Figure 9B). Additionally, IRAK-M mRNA levels positively correlated with arginase expression in peripheral blood from IPF patients (Figure 9C). These data suggest a possible causal link between IRAK-M expression and alternative activation markers in circulating leukocytes of IPF patients.

Figure 9. Increased IRAK-M and arginase expression in peripheral blood from IPF patients.

Expression of IRAK-M (A) and arginase (B) were quantified from a previously published data set (28). RNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples from IPF (n=93) or normal healthy control patients (n=30). Data is expressed as intensity of gene expression and normalized in Expression Console using RMA method. C. The correlation between IRAK-M and arginase was assessed by Person correlation method.

Discussion

IRAK-M is an important regulator of both infectious and non-infectious lung injury; however, the contribution of this molecule to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis has yet to be determined. Using a murine model of experimental pulmonary fibrosis, we demonstrated that the presence of IRAK-M, specifically in the bone marrow compartment, promotes fibrogenesis resulting in increased lung injury and collagen deposition. The expression of IRAK-M in macrophages skews these cells towards a pro-fibrotic alternatively activated phenotype. Elevated collagen production was observed when alternatively activated WT macrophages or cell free supernatants from bleomycin challenged mice were co-cultured with fibroblasts. Additionally, inhibition of IL-13 in WT macrophages/fibroblasts resulted in decreased collagen expression in our co-culture system. These data shed light on the growing evidence that negative regulators of TLR signaling pathways play an important role not only in controlling inflammatory responses but also in regulating lung repair and remodeling mechanisms.

Our data reveals a critical role for IRAK-M in promoting bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. IRAK-M−/− mice had increased early neutrophilic influx but reduced later accumulation of both neutrophils and macrophages. Diminished cellular influx into the lungs of IRAK-M−/− mice later after bleomycin challenge correlated with reduced lung injury. The enhanced early influx of neutrophils in IRAK-M−/− mice was anticipated and has been observed in other inflammatory model systems (25); however, reduced inflammation in these mice at later time points (seven days) is somewhat surprising. The skewing toward alternative macrophage activation and the production of IL-13 in bleomycin challenged WT mice may induce the production of chemotactic factors that facilitate later pulmonary inflammation. Previous work has shown IL-13 can induce CCL2 expression from the endothelium to promote leukocyte recruitment (32). Additionally, IL-13 is a known inducer of periostin, which can mediate cellular recruitment (33). However, we did not observe significant differences in the expression of CCL2 or periostin in bleomycin-challenge IRAK-M deficient mice as compared to WT animals (data not shown). Protection against lung injury in bleomycin-challenged IRAK-M−/− mice also suggested that IRAK-M could be promoting epithelial cell death. Our laboratory has previously shown that IRAK-M impairs the production of antioxidant molecules from AECs after hyperoxic lung injury (26). Although we observed a modest but significant increase in IRAK-M mRNA expression in AECs after bleomycin challenge (Supplemental Figure 1A), we did not detect differences in expression of glutathione peroxidase-2 and heme-oxygenase-1 in AECs after injury (data not shown). These data, along with our chimera results, suggest that expression of IRAK-M in AECs or other structural cells does not meaningfully contribute to the fibroproliferative response after bleomycin administration.

Previous work has suggested a possible role for IRAK-M in remodeling and repair events processes. Specifically, genetic deletion of this negative TLR regulator protected mice against acute kidney injury (AKI) and myocardial infarction (21, 34). In these models, IRAK-M−/− mice have increased expression of profibrotic mediators and enhanced renal fibrosis after kidney injury (34) and enhanced myocardial inflammation and adverse remodeling post-infarction (21). Our findings are somewhat at odds with these reports. An important distinction is that in these aforementioned injury models, classically activated pro-inflammatory macrophages promote disease in both AKI and myocardial infarctions models (35, 36); whereas in the bleomycin model, classically activated macrophages prevent the development of pulmonary fibrosis (9, 11, 37, 38). These contrasting results highlight how in the influence of macrophages on reparative processes is highly contextual and clearly dictated by the nature of the inciting event.

Although differences in the role of IRAK-M in regulating injury exist, a consistent theme across disease states is that IRAK-M promotes alternative activation of macrophages. Our data demonstrate that after bleomycin challenge or incubation with rmIL-13, IRAK-M−/− lung macrophages maintain a classically activated phenotype (as indicated by decreased Fizz1 and arginase expression, increased iNOS expression and reduced STAT-6 phosphorylation) compared to WT macrophages (Figure 6 and 7). This is not a lung specific phenomenon, as WT BMDM also displayed increased expression of Fizz1 and Arginase when treated with rmIL-13 in vitro compared to BMDM from IRAK-M−/− mice (Figure 7C). Previous groups have examined arginase expression in whole lung tissue from IPF patients and have reported conflicting results (10, 11). We found increased arginase levels in both WT lung macrophages from bleomycin challenged mice, as well as peripheral blood cells isolated from IPF patients. Interestingly, we have also shown a positive correlation between expression of arginase and IRAK-M in peripheral blood from IPF patients (Figure 9), suggesting a possible causal link between IRAK-M and alternative macrophage activation in these subjects. Similarly, after kidney injury, IRAK-M−/− macrophages expressed elevated TNF-α and iNOS while showing no differences in the production of mannose receptor or arginase (34). Additionally, our group demonstrated that IRAK-M-deficient macrophages associated with tumors were skewed towards a classically activated rather than alternatively activated phenotype (23). Collectively, these studies suggest that IRAK-M is required for alternative activation of macrophages. It should be noted, that in all of these studies macrophage activation was measured by mRNA expression of known markers or production of pro-inflammatory mediators after stimulation rather than with functional assays. It has yet to be determined whether IRAK-M alters the ability of macrophages to differentially metabolize arginine into either nitric oxide via classical activation or urea through alternative activation.

Mechanisms leading to upregulation of IRAK-M in our model have not been completely defined. Previous work has shown that a variety of endogenous molecules, including hyaluronan, collagen, fibronectin and other matrix components can bind to TLRs and induce intracellular signaling pathways (13). We have yet to identify the TLR ligand in our bleomycin injury model. It has been shown that IRAK-M can be induced in response to several pathogen associated molecular patterns, most notably LPS. There are a number of factors present in the lung microenvironment regulating injury and reparative responses, which may do so by regulating the expression of IRAK-M (22, 25, 26). In particular, we found that the profibrotic mediator IL-13 induced IRAK-M expression in lung macrophages, an effect similar to that previously shown in airway epithelial cells (22). The endogenous lung molecule, surfactant protein A, can also stimulate IRAK-M expression in human macrophages (39). A recent report demonstrated that collagen monomers upregulate alternatively activated makers in human alveolar macrophages, which suggests an amplification loop between macrophage activation and extracellular matrix molecules (40). The contribution of IRAK-M to collagen-induced alternative activation was not explored. Alternatively activated macrophages can also produce collagen which could lead to increased fibrosis (41). To this end, we measured collagen expression in WT and IRAK-M−/− macrophages treated with rmIL-13 in vitro, and observed no difference in mRNA expression of collagen in any of these groups (data not shown).

Our findings indicate that IRAK-M−/− mice produce less IL-13 after challenge (Figure 5A). Previous work has shown the importance of IL-13 in the development and maintenance of pulmonary fibrosis (5, 6). Several clinical trials are currently underway to determine whether inhibition of IL-13 can ameliorate or halt the progression of pulmonary fibrosis (1). Using a unique humanized SCID pulmonary fibrosis model, inhibition of IL-13 blocks lung remodeling after the establishment of fibrosis as well as promoting lung repair and restoring epithelial integrity (42). We also observed reduced expression of IL-13 from IRAK-M deficient macrophages harvested from bleomycin-challenged mice ex-vivo. The precise mechanism accounting for reduced IL-13 production in IRAK-M deficient cells is unclear, but we found impaired activation of STAT-6 in IRAK-M−/− macrophages, a transcription factor required for alternative macrophage activation and IL-13 production. Recently it has been reported that IL-13 stimulated platelet-derived growth factor induced collagen I production in airway fibroblast in a JAK/STAT6 dependent mechanism (43). While lung macrophages are thought to be a major cellular source of IL-13 during fibrogenesis, there are other cell types that may also contribute to IL-13 production. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis has been shown to be a T cell independent model, therefore production of IL-13 by this cell population is likely not responsible for regulating fibrogeneisis in our model (44). However, a novel population of cells, type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) have recently been shown to drive collagen deposition after bleomycin challenge, and increased numbers of ILC2s were found in the lungs of pulmonary fibrosis patients (45). More importantly it has been shown that ILC2s can promote alternative activation of macrophages via the production of IL-13 (46). Whether these cells express IRAK-M and whether IRAK-M regulates IL-13 production in these cells is an ongoing area of investigation.

In summary, our study illuminates a novel role of IRAK-M in regulating macrophage activation phenotypes and fibrogenesis during the evolution of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. This work motivates future studies to explore the pathogenic role of IRAK-M in IPF and as a potential biomarker in pulmonary fibrosis patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Carol Wilke for her animal expertise and help with experimental setup.

This work was supported by Parker B. Francis Fellowship and InterMune Junior faculty award (MNB), R01HL097564 and R01HL123535 (TJS), T32HL007749 (TJS), R01HL119682 (UB), and R01HL115618 (BBM).

References

- 1.Rafii R, Juarez MM, Albertson TE, Chan AL. A review of current and novel therapies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of thoracic disease. 2013;5:48–73. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.12.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore BB, Hogaboam CM. Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2008;294:L152–L160. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00313.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minty A, Chalon P, Derocq JM, Dumont X, Guillemot JC, Kaghad M, Labit C, Leplatois P, Liauzun P, Miloux B, et al. Interleukin-13 is a new human lymphokine regulating inflammatory and immune responses. Nature. 1993;362:248–250. doi: 10.1038/362248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolodsick JE, Toews GB, Jakubzick C, Hogaboam C, Moore TA, McKenzie A, Wilke CA, Chrisman CJ, Moore BB. Protection from fluorescein isothiocyanate-induced fibrosis in IL-13-deficient, but not IL-4-deficient, mice results from impaired collagen synthesis by fibroblasts. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:4068–4076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakubzick C, Choi ES, Joshi BH, Keane MP, Kunkel SL, Puri RK, Hogaboam CM. Therapeutic attenuation of pulmonary fibrosis via targeting of IL-4- and IL-13-responsive cells. Journal of immunology. 2003;171:2684–2693. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock A, Armstrong L, Gama R, Millar A. Production of interleukin 13 by alveolar macrophages from normal and fibrotic lung. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1998;18:60–65. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.1.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SW, Ahn MH, Jang HK, Jang AS, Kim DJ, Koh ES, Park JS, Uh ST, Kim YH, Park JS, Paik SH, Shin HK, Youm W, Park CS. Interleukin-13 and its receptors in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: clinical implications for lung function. Journal of Korean medical science. 2009;24:614–620. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.4.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Lanone S, Wang X, Koteliansky V, Shipley JM, Gotwals P, Noble P, Chen Q, Senior RM, Elias JA. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor beta(1) The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:809–821. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons MA, MacKinnon AC, Ramachandran P, Dhaliwal K, Duffin R, Phythian-Adams AT, van Rooijen N, Haslett C, Howie SE, Simpson AJ, Hirani N, Gauldie J, Iredale JP, Sethi T, Forbes SJ. Ly6Chi monocytes direct alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage regulation of lung fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;184:569–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1719OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitowska K, Zakrzewicz D, Konigshoff M, Chrobak I, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Bulau P, Eickelberg O. Functional role and species-specific contribution of arginases in pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2008;294:L34–L45. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00007.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mora AL, Torres-Gonzalez E, Rojas M, Corredor C, Ritzenthaler J, Xu J, Roman J, Brigham K, Stecenko A. Activation of alveolar macrophages via the alternative pathway in herpesvirus-induced lung fibrosis. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2006;35:466–473. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0121OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Z, Zhu Y, Lui B, Zhao W, Chen Y. Effects of alveolar macrophage conditioned media from interstitial lung disease patients on the procollagen mRNA expression in human lung fibroblasts. Chin Med Sci J. 1996;11:25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang D, Liang J, Li Y, Noble PW. The role of Toll-like receptors in non-infectious lung injury. Cell research. 2006;16:693–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, Homer RJ, Goldstein DR, Bucala R, Lee PJ, Medzhitov R, Noble PW. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nature medicine. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paun A, Fox J, Balloy V, Chignard M, Qureshi ST, Haston CK. Combined Tlr2 and Tlr4 deficiency increases radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2010;77:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brickey WJ, Neuringer IP, Walton W, Hua X, Wang EY, Jha S, Sempowski GD, Yang X, Kirby SL, Tilley SL, Ting JP. MyD88 provides a protective role in long-term radiation-induced lung injury. International journal of radiation biology. 2012;88:335–347. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.652723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samara KD, Antoniou KM, Karagiannis K, Margaritopoulos G, Lasithiotaki I, Koutala E, Siafakas NM. Expression profiles of Toll-like receptors in non-small cell lung cancer and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. International journal of oncology. 2012;40:1397–1404. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu HZ, Yang HZ, Mi S, Cui B, Hua F, Hu ZW. Toll like receptor 2 mediates bleomycin-induced acute lung injury, inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Yao xue xue bao = Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. 2010;45:976–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada K, Isse K, Sato Y, Ozaki S, Nakanuma Y. Endotoxin tolerance in human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cells is induced by upregulation of IRAK-M. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2006;26:935–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi N, Honda T, Domon H, Nakajima T, Tabeta K, Yamazaki K. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-M in gingival epithelial cells attenuates the inflammatory response elicited by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Journal of periodontal research. 2010;45:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen W, Saxena A, Li N, Sun J, Gupta A, Lee DW, Tian Q, Dobaczewski M, Frangogiannis NG. Endogenous IRAK-M attenuates postinfarction remodeling through effects on macrophages and fibroblasts. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32:2598–2608. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Q, Jiang D, Smith S, Thaikoottathil J, Martin RJ, Bowler RP, Chu HW. IL-13 dampens human airway epithelial innate immunity through induction of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase M. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012;129:825–833. e822. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Standiford TJ, Kuick R, Bhan U, Chen J, Newstead M, Keshamouni VG. TGF-beta-induced IRAK-M expression in tumor-associated macrophages regulates lung tumor growth. Oncogene. 2011;30:2475–2484. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng JC, Cheng G, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Kobayashi K, Flavell RA, Standiford TJ. Sepsis-induced suppression of lung innate immunity is mediated by IRAK-M. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2532–2542. doi: 10.1172/JCI28054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seki M, Kohno S, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Bhan U, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, Standiford TJ. Critical role of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-M in regulating chemokine-dependent deleterious inflammation in murine influenza pneumonia. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:1410–1418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballinger MN, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Bhan U, Horowitz JC, Moore BB, Pinsky DJ, Flavell RA, Standiford TJ. TLR signaling prevents hyperoxia- induced lung injury by protecting the alveolar epithelium from oxidant-mediated death. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:356–364. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore BB, Paine R, 3rd, Christensen PJ, Moore TA, Sitterding S, Ngan R, Wilke CA, Kuziel WA, Toews GB. Protection from pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of CCR2 signaling. Journal of immunology. 2001;167:4368–4377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tateda K, Deng JC, Moore TA, Newstead MW, Paine R, 3rd, Kobayashi N, Yamaguchi K, Standiford TJ. Hyperoxia mediates acute lung injury and increased lethality in murine Legionella pneumonia: the role of apoptosis. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:4209–4216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corti M, Brody AR, Harrison JH. Isolation and primary culture of murine alveolar type II cells. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1996;14:309–315. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.4.8600933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubbard LL, Ballinger MN, Wilke CA, Moore BB. Comparison of conditioning regimens for alveolar macrophage reconstitution and innate immune function post bone marrow transplant. Experimental lung research. 2008;34:263–275. doi: 10.1080/01902140802022518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang IV, Luna LG, Cotter J, Talbert J, Leach SM, Kidd R, Turner J, Kummer N, Kervitsky D, Brown KK, Boon K, Schwarz MI, Schwartz DA, Steele MP. The peripheral blood transcriptome identifies the presence and extent of disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PloS one. 2012;7:e37708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goebeler M, Schnarr B, Toksoy A, Kunz M, Brocker EB, Duschl A, Gillitzer R. Interleukin-13 selectively induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 synthesis and secretion by human endothelial cells. Involvement of IL-4R alpha and Stat6 phosphorylation. Immunology. 1997;91:450–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuoka M, Shiraishi H, Ohta S, Suzuki S, Arima K, Aoki S, Toda S, Inagaki N, Kurihara Y, Hayashida S, Takeuchi S, Koike K, Ono J, Noshiro H, Furue M, Conway SJ, Narisawa Y, Izuhara K. Periostin promotes chronic allergic inflammation in response to Th2 cytokines. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:2590–2600. doi: 10.1172/JCI58978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lech M, Grobmayr R, Ryu M, Lorenz G, Hartter I, Mulay SR, Susanti HE, Kobayashi KS, Flavell RA, Anders HJ. Macrophage phenotype controls long- term AKI outcomes--kidney regeneration versus atrophy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25:292–304. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujita E, Shimizu A, Masuda Y, Kuwahara N, Arai T, Nagasaka S, Aki K, Mii A, Natori Y, Iino Y, Katayama Y, Fukuda Y. Statin attenuates experimental anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis together with the augmentation of alternatively activated macrophages. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:1143–1154. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Y, Zhang H, Lu Y, Bai H, Xu Y, Zhu X, Zhou R, Ben J, Xu Y, Chen Q. Class A scavenger receptor attenuates myocardial infarction-induced cardiomyocyte necrosis through suppressing M1 macrophage subset polarization. Basic research in cardiology. 2011;106:1311–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gharib SA, Johnston LK, Huizar I, Birkland TP, Hanson J, Wang Y, Parks WC, Manicone AM. MMP28 promotes macrophage polarization toward M2 cells and augments pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2014;95:9–18. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H, Han G, Liu H, Chen J, Ji X, Zhou F, Zhou Y, Xie C. The development of classically and alternatively activated macrophages has different effects on the varied stages of radiation-induced pulmonary injury in mice. Journal of radiation research. 2011;52:717–726. doi: 10.1269/jrr.11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen HA, Rajaram MV, Meyer DA, Schlesinger LS. Pulmonary surfactant protein A and surfactant lipids upregulate IRAK-M, a negative regulator of TLR-mediated inflammation in human macrophages. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2012;303:L608–L616. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00067.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stahl M, Schupp J, Jager B, Schmid M, Zissel G, Muller-Quernheim J, Prasse A. Lung collagens perpetuate pulmonary fibrosis via CD204 and M2 macrophage activation. PloS one. 2013;8:e81382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osterholzer JJ, Olszewski MA, Murdock BJ, Chen GH, Erb-Downward JR, Subbotina N, Browning K, Lin Y, Morey RE, Dayrit JK, Horowitz JC, Simon RH, Sisson TH. Implicating exudate macrophages and Ly-6C(high) monocytes in CCR2-dependent lung fibrosis following gene-targeted alveolar injury. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:3447–3457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray LA, Zhang H, Oak SR, Coelho AL, Herath A, Flaherty KR, Lee J, Bell M, Knight DA, Martinez FJ, Sleeman MA, Herzog EL, Hogaboam CM. Targeting IL-13 With Tralokinumab Attenuates Lung Fibrosis and Epithelial Damage in a Humanized SCID IPF Model. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2013 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Zhu Y, Feng W, Pan Y, Li S, Han D, Liu L, Xie X, Wang G, Li M. Platelet-derived growth factor mediates interleukin-13-induced collagen I production in mouse airway fibroblasts. Journal of biosciences. 2014;39:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s12038-014-9454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helene M, Lake-Bullock V, Zhu J, Hao H, Cohen DA, Kaplan AM. T cell independence of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1999;65:187–195. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hams E, Armstrong ME, Barlow JL, Saunders SP, Schwartz C, Cooke G, Fahy RJ, Crotty TB, Hirani N, Flynn RJ, Voehringer D, McKenzie AN, Donnelly SC, Fallon PG. IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells induce pulmonary fibrosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:367–372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315854111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Chawla A, Locksley RM. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:535–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.