Abstract

Background

BRAF is a proto-oncogene encoding a serine/threonine protein kinase which promotes cell proliferation and survival. BRAF mutations are commonly seen in melanoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma. We aimed to investigate the prevalence and clinicopathological features of BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases submitted for routine mutation testing at our institution.

Methods

Mutation analysis for BRAF, EGFR and KRAS was performed using Sequenom MassARRAY platform with OncoCarta panel v1.0. Pathological features were reviewed and immunohistochemistry for BRAF V600E was also performed.

Results

Seven out of 273 cases (2.6%) had BRAF mutations (three males and four females, median age 70 years, all smokers), with six adenocarcinomas and one NSCLC, not otherwise specified (NOS). All had wild-type EGFR and KRAS. The identified BRAF mutations were V600E (4/7, 58%), K601N, L597Q and G469V. BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry was positive in two cases with V600E and negative in one case with K601N (tissue available in three cases only). No significant difference in age or gender was found (BRAF mutant vs. wild-type).

Conclusions

BRAF mutations occur in a small proportion of NSCLC that lack other driver mutations. The clinicopathological profile differs from that of EGFR mutant tumours. The potential benefits of BRAF-inhibitors should be investigated.

Keywords: Lung cancer, BRAF mutation, genetic testing

Introduction

The discovery of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has allowed effective targeted therapy with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients that harbour these mutations (1). However, the majority of NSCLC cases have wild-type EGFR and it is now known that many other mutations can drive oncogenic pathways, including KRAS and less commonly, BRAF (2). BRAF is a proto-oncogene encoding a serine/threonine protein kinase which is a downstream effector protein of RAS and transduces signalling through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway to promote cell proliferation and survival. This pathway functions downstream of various receptor tyrosine kinases such as EGFR and is a key mediator of oncogenesis (3).

BRAF mutations are commonly seen in a range of malignancies, including hairy-cell leukemia (100%) (4), melanoma (~40%) (5), papillary thyroid carcinoma (30-50%) and colorectal carcinoma (~10%) (6). The V600E mutation has been shown to constitutively activate BRAF which phosphorylates the downstream effectors MEK and subsequently ERK (7). ERK, in turn, activates transcription factors such as c-fos and Elk-1, driving cell cycle progression and survival (8). The importance of the BRAF pathway is well established in melanoma, as BRAF inhibitors have been shown to significantly increase progression free survival of patients with advanced stage melanoma harbouring the BRAF V600E mutation (9). This raises the possibility that BRAF mutations may also be a feasible target in NSCLC. BRAF mutations in NSCLC are not well characterised in the literature due to their low prevalence. In this study we aimed to investigate the prevalence and clinicopathological features of BRAF mutations in NSCLC.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed 273 NSCLC cases that underwent mutation testing upon request of the treating oncologist at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital between March 2012 and March 2014. The patients underwent either a resection or a diagnostic procedure (biopsy or cytological specimen) and the tissue was formalin fixed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The H&E sections were reviewed by a pathologist (SOT or WC) to ensure adequate tumour cells were present and to mark representative areas for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction. Histological subtypes were classified according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification (10). This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

Mutation detection

DNA was extracted from the formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue using NucleoSpin FFPE DNA Kit (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction with 2 hr proteinase digestion. The quantity of the extracted DNA was assessed using Qubit® Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Mulgrave, Australia). A minimum of 300 ng of DNA was required for optimal mutational analysis. Samples were amplified for 238 variant targets in a 24-multiplex PCR using the OncoCarta Panel v1.0 Kit (ABL1, AKT1, AKT2, BRAF, CDK, EGFR, ERBB2, FGFR1, FGFR3, FLT3, JAK2, KIT, MET, HRAS, KRAS, NRAS, PDGFR, PIK3CA, and RET) and analyzed based on the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) technology on the Sequenom MassArray platform (11,12). The targeted mutations in the 19 oncogenes comprising the OncoCarta v1.0 Panel are reported to be biologically significant in carcinogenesis or progression in a range of malignancies. These mutational analyses and immunohistochemistry described below were performed at an Australian National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA) accredited medical laboratory.

Immunohistochemistry

BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry was performed on sections cut at four microns. Tissue was pre-treated on a Ventana Benchmark Ultra (Roche) with CC1 (Roche) for 64 minutes. The anti-BRAF (VE1) mouse monoclonal antibody (Spring Bioscience) was used at 1:100 dilution with 16 minutes incubation. Staining was performed using the OptiView DAB Immunohistochemistry Detection kit (Roche) for 8 minutes. Cases with 1+, 2+ and 3+ staining were regarded as positive and cases with no staining were regarded as negative.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the difference in gender distribution between BRAF wild-type and mutant patients while Welch’s t-test was used to evaluate the age difference. Data were analysed using the R environment for statistical computing (13).

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. A total of 273 cases of NSCLC were tested and 7 (2.6%) were found to have BRAF mutations. Of patients with BRAF mutations, there were three males and four females, median age 70 years, range from 51 to 76 years. All seven patients were former smokers with smoking history ranged from 3 to 90 pack years. BRAF wild-type was found in 266 cases with 141 males and 125 females, median age 66.5 years. There was no significant difference in gender distribution (P=0.71) or age (P=0.65) between BRAF wild-type and mutant patients. Due to incomplete data on smoking history and tumour type in the BRAF wild-type group, statistical analysis could not be performed.

Table 1. Patient clinical characteristics and BRAF genotype.

| Patient no. | Age (years) | Gender | Smoking status | Procedure | Predominant histological subtype | Other components | BRAF mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | F | Ex-smoker 15 pk yrs | Lung FNA | Non-small cell carcinoma, NOS | V600E | |

| 2 | 57 | F | Ex-smoker pk yrs not known | Resection | Adenocarcinoma—lepidic | Papillary | G469V |

| 3 | 70 | F | Ex-smoker 10 pk yrs | Resection | Adenocarcinoma—micropapillary | Lepidic | V600E |

| 4 | 70 | M | Ex-smoker 90 pk yrs | Lung core biopsy | Adenocarcinoma—acinar | Papillary and lepidic | K601N |

| 5 | 73 | F | Ex-smoker 40 pk yrs | Bronchial washing | Adenocarcinoma | V600E | |

| 6 | 74 | M | Ex-smoker 40 pk yrs | Bronchial biopsy | Adenocarcinoma | L597Q | |

| 7 | 76 | M | Ex-smoker 3 pk yrs | Resection | Adenocarcinoma—micropapillary | Acinar | V600E |

F, female; M, male; NOS, not otherwise specified.

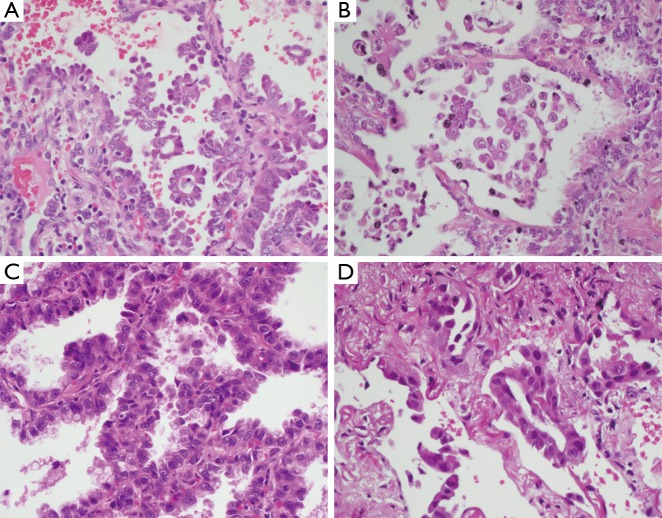

Six cases were adenocarcinomas and one case was a non-small cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS). The tumour diagnosed as non-small cell carcinoma, NOS, was from a fine needle aspiration specimen. Two cases of adenocarcinoma were diagnosed on bronchial biopsy or washing. One case was diagnosed on core biopsy showing a mixture of acinar, papillary and lepidic patterns. In patients who underwent a resection, the histological subtypes were lepidic predominant with papillary component, micropapillary predominant with lepidic component and micropapillary predominant with acinar component. Representative H&E sections are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A,B) Micropapillary pattern in patients 3 and 7 respectively; (C) lepidic pattern in patient 2; (D) acinar pattern in patient 4. (H&E 400× magnification).

BRAF mutation genotypes

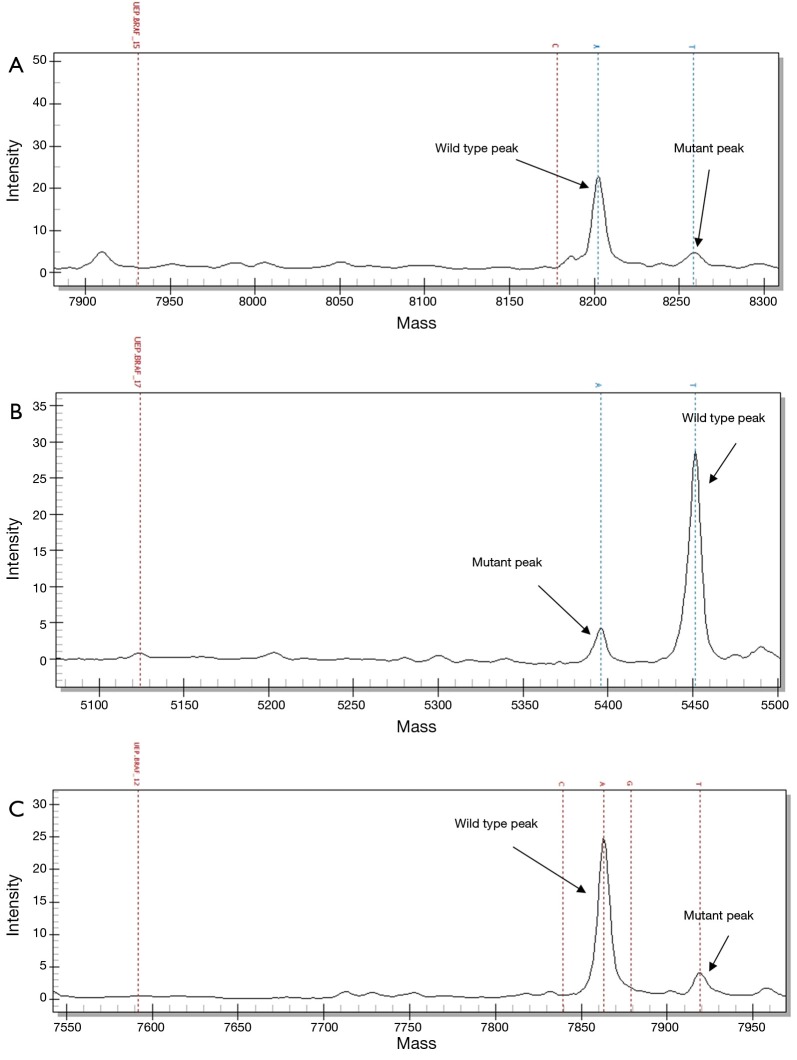

Four BRAF mutation genotypes were identified. Three mutations were located in exon 15 which included V600E (c.1799T>A, 58%, n=4), K601N (c.1803A>T, 14%, n=1) and L597Q (c.1790T>A, 14%, n=1). One mutation was found in exon 11 which was G469V (c.1406G>T, 14%, n=1). Representative spectra are shown in Figure 2. A female predominance of V600E mutations was noted (3 out of 4 V600E mutations). Furthermore, both patients with a micropapillary component harboured V600E mutation. No patient with a BRAF mutation had a concomitant EGFR or KRAS mutation.

Figure 2.

Mass spectrometry of PCR products showing BRAF mutations (all three profiles showing the changes at the antisense strand of DNA). (A) BRAF V600E mutation (patient 1) with a mutant adenine (A) peak substituting for thymine (T) at position 1799 (c.1799T>A); (B) BRAF K601N mutation (patient 4) with a mutant T peak substituting for A (c.1803A>T); (C) BRAF L597Q mutation (patient 6) with a mutant A peak substituting for T (c.1790T>A).

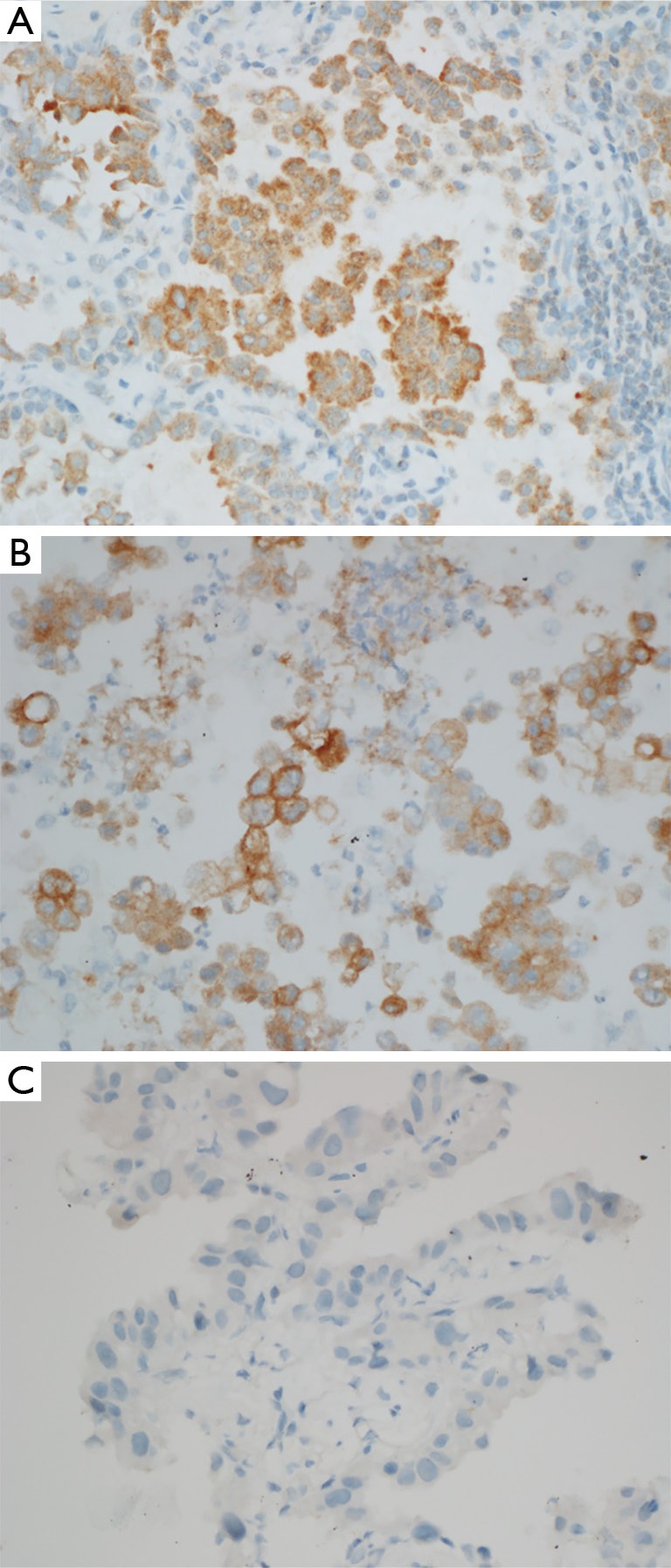

Immunohistochemistry

Due to limited availability of tissue, BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry was only performed in three cases. BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry was positive in two cases with V600E mutation and negative in one case with K601N mutation (Figure 3). Thus the immunohistochemistry results were consistent with the Sequenom MassArray platform results.

Figure 3.

BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry for (A) patient 3 (V600E mutation), (B) patient 5 (V600E mutation) and (C) patient 4 (K601N mutation). (400× magnification).

Discussion

In our population of Australian patients with NSCLC that underwent mutation testing, we found BRAF mutations occurred in 2.6% of patients who were all former smokers. This is consistent with other studies reporting BRAF mutation prevalence between 2-5% in NSCLC (14-16). While this is much less common than EGFR mutations that occur in approximately 15% of lung adenocarcinomas in Western populations (17), there were approximately 6,000 new cases of NSCLC diagnosed in Australia in 2007 (18), giving a predicted number of 156 patients with BRAF mutant lung cancer. These patients could potentially benefit from targeted therapy as BRAF V600E NSCLC has shown some response to dabrafenib (19). The prevalence rate is only slightly lower than that of ALK gene rearrangements that are found in ~3-5% of lung adenocarcinomas (20).

We found all patients with BRAF mutation had a smoking history, in contrast with EGFR mutations which commonly occur in non-smokers (21). Although others have also reported an association between BRAF mutation and smoking (16), one study reported V600E mutation to be associated with non-smokers while non-V600E mutations were associated smokers (14). Discrepancies between studies may be due to low numbers of BRAF mutant cases in each study, relating to the low prevalence of BRAF mutations in NSCLC.

A potential limitation of the targeted approach to mutation detection employed in the current study is that very rare mutations not on the OncoCarta panel may not be detected, such as BRAF mutations involving amino acids 421, 436, 439 and 471. However, these mutations represent less than 2% of all reported BRAF mutations in NSCLC (22), making it highly unlikely for the overall BRAF mutation prevalence to be under-represented in the current study. Furthermore our testing is more comprehensive than that performed by many centres who currently focus only of the BRAF V600 codon.

Although the current study did not find a significant difference in gender distribution or age between BRAF wild-type and mutant patients, the small number of patients in the BRAF mutant group makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Interestingly, a predominance of BRAF V600E mutation in females has been reported by others (14) while we found a non-statistically significant trend towards female predominance. BRAF mutation is also more commonly found in females in colorectal cancer (23,24). This finding is akin to the female predominance of EGFR mutations and may represent a similar underlying mechanism. An association between EGFR mutation and oestrogen receptor has been found, possibly indicating a hormonally driven phenomenon (25). However, a clear mechanism has yet to be substantiated.

The BRAF V600E mutation has been previously reported to be associated with the aggressive micropapillary subtype of lung adenocarcinoma (14,26). This finding is supported by the current study as both patients with a micropapillary component showed BRAF V600E mutation. However, it is difficult to be conclusive due to the small number of patients in the current study precluding statistical analysis.

The most common BRAF mutation in melanoma is the V600E mutation, which accounts for more than 90% of mutations (6). However, the current study shows that BRAF V600E mutation only accounts for 58% of mutations in NSCLC. This finding is supported by others who found the non-V600E mutation rate to be between 50-89% (16,27). Although the biological significance of this is unknown, this raises the possibility that BRAF-related oncogenesis in NSCLC arises from a different mechanism compared to melanomas with V600E mutations. It has been shown that the V600E mutation confers a much higher kinase activity compared to other mutations within the kinase domain (7). The G469V mutation found in the current study occurs in the P-loop which is the ATP binding site. Mutations within the P-loop have been shown to have a lower activity compared to wild-type BRAF (7), therefore whether these mutations drive oncogenesis is uncertain. Similarly, rare mutations at codons 439 and 440 (AKT phosphorylation motif) have been reported in NSCLC and they do not increase the oncogenic properties of BRAF (28). This indicates that the genotype of the BRAF mutation may be an important therapeutic consideration. Unfortunately, there is currently only limited phase I clinical trial data for RAF inhibitors in NSCLC (19) and the significance of the different mutation spectrum remains uncertain.

In conclusion, the current study confirmed that a small proportion of NSCLC patients harbour BRAF mutations. Their clinicopathological characteristics appear to differ from patients with EGFR mutations and their genotype differs from that found in melanoma. Further work needs to be done to determine whether this small subset of patients will benefit from BRAF inhibitors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Thang Tran for performing the statistical analysis. WC and SOT have received funding from National Foundation for Medical Research and Innovation.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tsao AS, Papadimitrakopoulou V. The importance of molecular profiling in predicting response to epidermal growth factor receptor family inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer: focus on clinical trial results. Clin Lung Cancer 2013;14:311-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper WA, Lam DC, O’Toole SA, et al. Molecular biology of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S479-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature 2006;441:424-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiacci E, Trifonov V, Schiavoni G, et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2305-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platz A, Egyhazi S, Ringborg U, et al. Human cutaneous melanoma; a review of NRAS and BRAF mutation frequencies in relation to histogenetic subclass and body site. Mol Oncol 2008;1:395-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002;417:949-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell 2004;116:855-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torii S, Yamamoto T, Tsuchiya Y, et al. ERK MAP kinase in G cell cycle progression and cancer. Cancer Sci 2006;97:697-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:358-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/American thoracic society/European respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:244-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet 2007;39:347-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacConaill LE, Campbell CD, Kehoe SM, et al. Profiling critical cancer gene mutations in clinical tumor samples. PLoS One 2009;4:e7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmid K, Oehl N, Wrba F, et al. EGFR/KRAS/BRAF mutations in primary lung adenocarcinomas and corresponding locoregional lymph node metastases. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:4554-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2046-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip PY, Yu B, Cooper WA, et al. Patterns of DNA mutations and ALK rearrangement in resected node negative lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:408-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Lung cancer in Australia: an overview. Cancer series no. 64. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falchook GS, Long GV, Kurzrock R, et al. Dabrafenib in patients with melanoma, untreated brain metastases, and other solid tumours: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2012;379:1893-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon B, Varella-Garcia M, Camidge DR. ALK gene rearrangements: a new therapeutic target in a molecularly defined subset of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer-molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med 2005;353:133-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes SA, Tang G, Bindal N, et al. COSMIC (the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer): a resource to investigate acquired mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:D652-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:466-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalady MF, Dejulius KL, Sanchez JA, et al. BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with distinct clinical characteristics and worse prognosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:128-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raso MG, Behrens C, Herynk MH, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors identifies a subset of NSCLCs and correlates with EGFR mutation. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:5359-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Oliveira Duarte Achcar R, Nikiforova MN, Yousem SA. Micropapillary lung adenocarcinoma: EGFR, K-ras, and BRAF mutational profile. Am J Clin Pathol 2009;131:694-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brose MS, Volpe P, Feldman M, et al. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res 2002;62:6997-7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikenoue T, Kanai F, Hikiba Y, et al. Functional consequences of mutations in a putative Akt phosphorylation motif of B-raf in human cancers. Mol Carcinog 2005;43:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]