Abstract

Background

Risk classification and prediction of prognosis in GIST is still a matter of debate. Data on the impact of age and gender as potential confounding factors are limited. Therefore we comprehensively investigated age and gender as independent risk factors for GIST.

Methods

Two independent patient cohorts (cohort I, n = 87 [<50 years]; cohort II, n = 125 [≥50 years]) were extracted from the multicentre Ulmer GIST registry including a total of 659 GIST patients retrospectively collected in 18 collaborative German oncological centers. Based on demographic and clinicopathological parameters and a median follow-up time of 4.3 years (range 0.56; 21.33) disease-specific-survival (DSS), disease-free-survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated.

Results

GIST patients older than fifty years showed significantly worse DSS compared to younger patients (p = 0.021; HR = 0.307, 95% CI [0.113; 0.834]). DSS was significantly more favorable in younger female GIST patients compared with elderly females (p = 0.008). Female gender resulted again in better prognosis in younger patients (p = 0.033).

Conclusions

Patient age (<50 years) and female gender were significantly associated with a more favourable prognosis in GIST. Extended studies are warranted to confirm our clinical results and to elucidate underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1054-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: GIST, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, Prognosis, Outcome, Age, Gender, Sex

Background

Based on the molecular pathogenesis of driver gain-of-function mutations in c-kit (80-90%) [1-4] and less frequently in the PDGFRα gene (5-10%), gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) became a molecular model tumor in oncology emphasized by the central role of receptor tyrosine kinases in their molecular pathogenesis and the availability of small molecule inhibitor therapy.

GIST occur with an annual incidence of 7 to 20 per million [5-9]. Most patients with GIST are diagnosed within the 7th decade [10,11]. Less than 10% of patients with GIST are younger than forty. There are also some single reports on pediatric GIST, which appear to be a different disease entity [12-14]. Although large-scale multi-centre studies are available (e.g. the population-based study from Sweden [5], the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database [10] and the AFIP studies [15,16], data are limited on the impact of age and gender related to risk classifications and/or prediction of prognosis in GIST. In particular it is still unclear whether prognosis of GIST in adult patients may be significantly altered by age (i.e. patients with an age younger than 50 years) and/or gender-related factors. Therefore, the aim of the present retrospective analysis was to elucidate comprehensively clinicopathological features of GIST patients younger than 50 years to identify potential age and gender-related effects on patient outcome.

Methods

Data of the independent multicentre Ulmer GIST registry were used to extract age-dependent patient cohorts (under and above 50 years of age at diagnosis) for further comparative analyses. Patient data of the multicentre GIST registry were retrospectively obtained from 18 collaborative oncological centres in Southern-Germany between 2004 and 2009. Substantial demographic and/or social selection bias of patients could be excluded since all contributing centres are part of general or university hospitals. As previously outlined in detail [17], data registration of the multicentre Ulmer GIST registry is strictly based on clearly defined methodological criteria, such as Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement and the User’s Guide to Registries Evaluating Patient Outcomes [18-21].

Briefly, all patients from study centres with proven diagnosis of GIST were consecutively included unless they refused consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Ulm (No. 90 + 91/2006). Diagnosis of GIST was based on currently applied diagnostic criteria [16,22] using histological characteristics (e.g. highly cellular spindle/epithelioid/mixed cell tumors), immunohistochemical status (positivity for KIT or PDGFRα) and mutational analysis of relevant c-kit and PDGFRα exons. Clinical data were retrospectively reviewed based on the hospital records including medical history and clinical follow-up. In addition, personal contact as well as telephone interview and/or review of medical charts in case of re-admission of patients served for data acquisition. The following parameters were defined as the most relevant clinical and clinicopathological features for the present work: age, gender, tumor localization (stomach vs. small intestine), histological subtype (spindle cell tumors vs. epithelioid/mixed cell tumors), primary tumor size (cut-off 1, 5 and 10 cm), mitotic rate (cut-off 5 and 10 per 50 HPF), immunohistochemical status of KIT or/and PDGFRα (if uncertain: mutational status), secondary malignancy (yes vs. no), risk classification according to Fletcher et al. [23] (i.e. high vs. non-high) and according to Miettinen et al. [15] (i.e. high vs. non-high), tumor recurrence and/or metastasis.

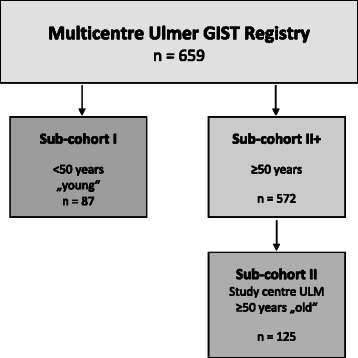

At the time of data analysis for the present study, the multicentre Ulmer GIST registry consisted of 659 GIST patients (Figure 1). Since a previous clinical study by Cao et al. [24] suggested an age of 50 years as significant cut-off for the discrimination between GIST patients with worse and good prognosis, we stratified patients from our Ulmer GIST registry accordingly. 87 of the 659 GIST patients (13.2%) were younger than 50 years and defined as sub-cohort I, “young”. To establish a control cohort with an age of ≥50 years at time of diagnosis, all remaining 572 GIST patients of the Ulmer GIST registry older than 50 years were defined as sub-cohort II+. To ensure highest completeness of clinical and follow up data, we extracted a sub-cohort from the sub-cohort II+ that included only those GIST patients that derived from the oncology center at the University Hospital of Ulm, finally encompassing a total of 125 GIST patients (study cohort II, “old”). The overall median follow-up time for both study groups, the sub-cohort I (“young”) and sub-cohort II (“old”), was 4.3 years (range 0.56; 21.33).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for study populations.

Statistical analyses

Two-sided χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test were applied, as appropriate, to check for differences of the demographic, clinical and clinicopathological parameters between the independent study-cohorts. Estimates for disease-free-survival (DFS), disease-specific-survival (DSS) and overall-survival (OS) were obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between Kaplan-Meier curves were investigated by the log-rank test. For analysis of DSS non GIST-related deaths were censored.

To prove the most relevant findings of the Kaplan-Meier analyses, an additional multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model has been established for DSS and DFS. The variables gender, age, tumor localization have been defined as the most relevant independent variables of the model. If applicable, the Hazard Ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated regarding tumor-related death and tumor recurrence and/or metastasis by applying univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. To exclude confounding of analyses by treatment of GIST patients with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, Kaplan-Meier analyses were recalculated, censoring all end-points and follow-ups after initiating of imatinib.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V19.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). Level of significance was set to α = 0.05. Since all results rely on testing retrospective data, interpretation of hypotheses was done in an explorative manner. Therefore an adjustment of the significance level due to multiple testing has been not performed.

Results

Table 1 comprises all demographic and clinicopathological data of GIST patients enrolled in sub-cohort I (“young”, <50 years) and sub-cohort II (“old”, ≥50 years). Whereas the gender ratio, the tumor localization and histotypes, tumor size, mitotic rate, and risk scores according to Fletcher et al. [23] and Miettinen et al. [15] were similar between both subgroups, some parameters differed age-dependently (Table 2). In patients older than 50 years small GIST tumors (<1 cm) (p = 0.002 (Fisher’s exact), OR = 11.2, 95%CI: 1.5, 87.0) as well as secondary malignancies were more frequent (p < 0.001 (χ2-Test), OR = 3.5 95% CI: 1.6, 7.2) and more GIST-related deaths occurred (p = 0.017 (Fisher’s exact), OR = 3.1, 95% CI: 1.1, 8.7). Syndromic diseases (Neurofibromatosis type 1, Carney triad) were found in three and four patients of sub-cohort I and II (both 3.4%), respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of GIST patients of sub-cohort I (<50 years, “young” ) and sub-cohort II (≥50 years, “old” )

| Parameter | Sub-cohort I (n = 87) | Sub-cohort II (n = 125) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 yr(“young”) | ≥50 yr(“old”) | ||||

| Age | |||||

| median (range, yr) | 41.7 (14.9;49.9) | 68.2 (50.9; 94.1) | |||

| Sex | n | % | n | % | |

| female | 48 | 55.2 | 68 | 54.4 | |

| male | 39 | 44.8 | 57 | 45.6 | |

| Localization | |||||

| stomach | 43 | 50.6 | 79 | 64.2 | |

| small intestine | 29 | 34.1 | 35 | 28.5 | |

| colorectum | 5 | 5.9 | 2 | 1.6 | |

| esophagus | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.8 | |

| EGIST | 3 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.4 | |

| n.d. | 4 | 4.7 | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Tumor size | |||||

| median (range, cm) | 5.5 (1.2; 27.0) | 4.5 (0.4;40.0) | |||

| Risk according to Fletcher et al. [23] | n | % | n | % | |

| high | 29 | 41.4 | 35 | 31.8 | |

| intermediate | 15 | 21.4 | 25 | 22.7 | |

| low | 17 | 24.3 | 31 | 28.2 | |

| very Low | 9 | 12.9 | 19 | 17.3 | |

| Risk according to Miettinen et al. [11] | |||||

| high | 22 | 33.3 | 30 | 29.7 | |

| intermediate | 10 | 15.2 | 7 | 6.9 | |

| low | 25 | 37.9 | 43 | 42.6 | |

| very Low | 9 | 13.6 | 21 | 20.8 | |

| Histological subtype | |||||

| spindle cell | 63 | 85.1 | 98 | 89.1 | |

| Epithelioid/mixed | 11 | 14.9 | 12 | 10.9 | |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||||

| KIT pos | 74 | 94.9 | 115 | 98.3 | |

| KIT neg | 4 | 5.1 | 2 | 1.7 | |

| CD34 pos | 48 | 82.8 | 84 | 84.0 | |

| CD34 neg | 10 | 17.2 | 16 | 16.0 | |

| S100 pos | 11 | 25.6 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| S100 neg | 32 | 74.4 | 68 | 98.6 | |

| Clinical data | |||||

| Metastasis atdiagnosis | 9 | 10.3 | 16 | 12.8 | |

| Secondneoplasia | 11 | 15.5 | 45 | 38.8 | |

| R0resection | 81 | 93.1 | 112 | 89.6 | |

| Tumor debulking | 4 | 4.6 | 7 | 7.2 | |

| Imatinib use | 24 | 27.6 | 27 | 21.6 | |

| Recurrenceof disease and/ormetastasis | |||||

| yes | 21 | 25.9 | 32 | 29.6 | |

| Follow up time | |||||

| mean (yr, ±SD) | 4.90 (3.39) | 5.65 (4.55) | |||

| median (range, yr) | 4.28 (0.59;16.31) | 4.57 (0.56;21.33) | |||

| deceased | 9 | 10.3 | 40 | 32.0 | |

| alive | 78 | 89.7 | 85 | 68.0 | |

| tumor-relateddeath | 5 | 5.7 | 20 | 16.0 | |

| Survival rate | % (n) | % (n) | |||

| DSS (yr1/yr3/yr5) | 98.5 (64)/96.6 (49)/96.6 (34) | 96.2 (93)/87.0 (67)/81.2 (44) | |||

| DFS (yr1/yr3/yr5) | 88.4 (57)/81.2 (41)/78.8 (29) | 79.0 (74)/74.2 (55)/69.9 (36) | |||

| OS (yr1/yr3/yr5) | 98.5 (64)/93.2 (49)/91.2 (34) | 90.8 (93)/77.4 (67)/67.0 (44) | |||

| Syndromal disease | 3xNF1 | 3.4% | 3x NF1 | 2.4% | |

| 1x Carney | 1% | ||||

yr, year; n.d., not defined; SD, standard deviation; DSS, disease specific survival; DSF, disease free survival; OS, overall survival; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; Carney, Carney triad (coexistence of GIST, paraganglioma and pulmonal chondroma).

Table 2.

Comparsion of demographic and clinicopathological parameters in sub-cohort I ( “young” , n = 87) versus sub-cohort II ( “old” , n = 125)

| Parameters | n | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age at diagnosis | <50 yr vs. >50 yr | 212 | <0.001 |

| Sex | male vs. female | 212 | 0.912 |

| Tumor localization | stomach vs. small intestine | 187 | 0.210 |

| GIST histotype | spindle vs. epitheliod/mixed | 184 | 0.426 |

| Tumor size | <1 cm vs. ≥1 cm | 199 | 0.002 |

| <5 cm vs. ≥5 cm | 199 | 0.524 | |

| <10 cm vs. ≥10 cm | 199 | 0.605 | |

| Mitotic rate | <5 vs. ≥5 / HPF | 174 | 0.902 |

| <10 vs. ≥10 / HPF | 173 | 0.982 | |

| Risk acc.to Fletcher et al. | high vs. non-high | 180 | 0.189 |

| Risk acc. to Miettinen et al. | high vs. non-high | 167 | 0.620 |

| R0resection | yes vs. no | 193 | 0.321 |

| TKI use (imatinib) | yes vs. no | 212 | 0.316 |

| Secondary malignancies | yes vs. no | 187 | <0.001 |

| Cancer related death | yes vs. no | 212 | 0.017 |

yr, year; HPF, high power field; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor;

*Two-sided χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test were applied as appropriate to check for differences between both study-cohorts.

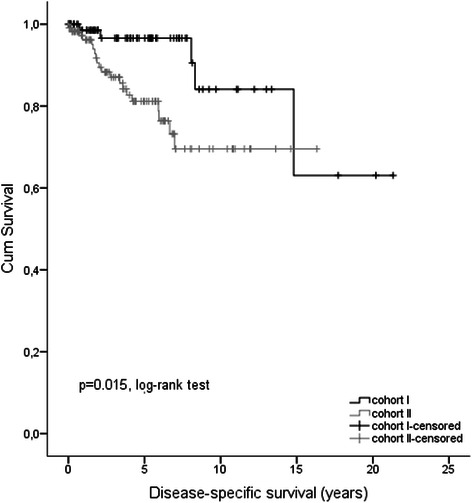

Survival analysis

At date of diagnosis the rate of metastasis was not different between sub-cohort I (10.3%) and sub-cohort II (12.8%; p = 0.586, Table 1). The outcome of GIST patients was generally more favourable in young patients (cohort I) vs. older patients (cohort II). DSS rates after 1-, 3- and 5-year follow-up in “young” vs. “old” patients were 98.5% vs. 96.2%, 96.6% vs. 87.0% and 96.6% vs. 81.2%, respectively. After 5-year follow up DSS was significantly better in GIST patients younger than 50 years (p = 0.015, log-rank-test; Figure 2). A multivariate Cox regression model adjusted for gender and tumor localization confirmed improved outcome for younger patients (p = 0.036, HR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.079, 0.921). Moreover, we elucidated whether age as a continuous variable is an independent prognostic factor. Again we could show that the older age was associated with an increased risk for DSS (p = 0.002, HR = 1.049, 95% CI: 1.018, 1.080) and OS (p < 0.0001; HR = 1.051, 95% CI: 1.029, 1.074).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of disease-specific survival (DSS) for GIST patients of study cohort I (<50 years at diagnosis, n = 87) versus study cohort II (≥50 years at diagnosis, n = 125).

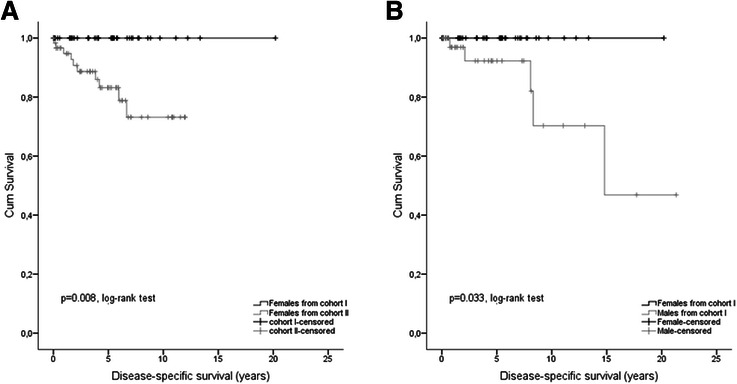

Next we investigated differences for DSS rates between “young” and “old” GIST patients (sub-cohort I vs. II) considering selected demographic and clinicopathological parameters as well as different risk scores as given in Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1. Most strikingly a more favourable DSS after 5 years was found in female “young” patients (p = 0.008, log-rank-test, Figure 3A), but not in men. Calculation of the corresponding HR failed since only censored events were observed in sub-cohort I. Moreover, DSS was better for “young” GIST patients with high risk classification according to Fletcher et al. [23] (p = 0.004;HR = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.04; 0.66), tumor size above 5 cm (p = 0.008; HR = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.01; 0.81), a mitotic rate ≥5/50 HPF (p = 0.026; HR = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.05; 0.95) and tumor localization in the stomach (p = 0.036; HR = 0.15, 95% CI:0.02; 1.17) according to univariate Cox regression models.

Table 3.

Disease-specific survival (DSS) for GIST patients <50 years (sub-cohort I, “young” ) versus ≥50 years (sub-cohort II, “old” ) related to GIST relevant clinicopathological parameters

| Parameter | Disease-specific survival (DSS) rates | p-value1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-cohort I (“young”) | Sub-cohort II (“old”) | |||||||

| n = 87 | n = 125 | |||||||

| 1 yr | 3 yr | 5 yr | 1 yr | 3 yr | 5 yr | |||

| Sex | male | 96.9% | 92,3% | 92,3% | 97,8% | 84,8% | 78,5% | 0.326 |

| female | 100% | 100% | 100% | 94,7% | 88,6% | 83,2% | 0.008 | |

| p-value 2 | 0.033 | 0.596 | ||||||

| Localization | Gaster | 97,2% | 97,2% | 97,2% | 97,0% | 88,0% | 83,4% | 0.036 |

| Small intestine | 100% | 93,8% | 93,8% | 96,4% | 88,5% | 78,6% | 0.267 | |

| p-value 2 | 0.225 | 0.813 | ||||||

| Histotype | Spindle | 100% | 97,4% | 97,4% | 96,4% | 90,8% | 83,5% | 0.028 |

| epitheliod/mixed | 100% | 100% | 100% | 91,7% | 66,7% | 66,7% | 0.061 | |

| p-value 2 | 0.695 | 0.097 | ||||||

| Size | <1 cm | - | - | - | 100,0% | 100,0% | 85,7% | - |

| ≥1 cm | 100% | 97,9% | 97,9% | 96,6% | 87,5% | 82,6% | 0.012 | |

| p-value 2 | - | 0.499 | ||||||

| Size | <5 cm | 96,8% | 92,2% | 92,2% | 100,0% | 94,5% | 90,9% | 0.630 |

| ≥5 cm | 100% | 100% | 100% | 94,1% | 83,8% | 76,3% | 0.008 | |

| p-value 2 | 0.462 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Size | <10 cm | 97,9% | 95,0% | 95,0% | 98,6% | 95,3% | 93,1% | 0.839 |

| ≥10 cm | 100% | 100% | 100% | 92,0% | 71,1% | 56,0% | 0.010 | |

| p-value 2 | 0.759 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mitotic rate | <5 / 50 HPF | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98,4% | 96,2% | 90,4% | 0.131 |

| ≥5 / 50 HPF | 100% | 100% | 100% | 91,6% | 73,7% | 66,7% | 0.026 | |

| p-value 2 | 0.038 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Mitotic rate | <10 / 50 HPF | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97,4% | 92,4% | 88,2% | 0.043 |

| ≥10 / 50 HPF | 100% | 100% | 100% | 89,7% | 68,6% | 56,1% | 0.025 | |

| p-value 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Risk (NIH) | high | 100% | 100% | 100% | 87,9% | 68,4% | 60,8% | 0.004 |

| non-high | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100,0% | 98,0% | 92,9% | 0.227 | |

| p-value | 0.027 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Risk (AFIP) | high | 100% | 100% | 100% | 89,4% | 70,5% | 61,7% | 0.018 |

| non-high | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98,5% | 94,4% | 89,4% | 0.084 | |

| p-value | 0.013 | <0.001 | ||||||

1Unadjustedp-values comparing data from study-cohort I vs. II considering DSS after 5 year follow-up.

2Unadjusted p-values comparing data within study-cohort I and II considering DSS rates after 5 year follow-up.

Figure 3.

Age and gender related outcome regarding DSS. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of disease-specific survival (DSS) for female GIST patients of study cohort I (<50 years at diagnosis) versus study cohort II (≥50 years at diagnosis). (B) Kaplan–Meier curves of disease-specific survival (DSS) for gender-related differences of GIST patients younger than 50 years at diagnosis (study cohort I).

Additional analyses regarding DSS after 5 years in relationship to demographic and clinicopathological parameters as well as different risk scores in each sub-cohort revealed a more favourable outcome in “young” female patients (p = 0.033,log-rank test; Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S2, Figure 3B) whereas DSS was not gender-specific different (p = 0.596) in sub-cohort II (“old"). Moreover DSS was improved in “young” patients with non-high risk GIST (p = 0.027) and with tumors characterized by a mitotic rate below 5/50 HPF (p = 0.038). DSS was also significantly improved in “old” patients with non-high risk GIST (p < 0.001, HR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.03; 0.31), in GIST with mitotic rate <10/50HPF (p < 0.001, HR = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.06; 0.39) and with tumors sized <5 cm (p = 0.012, HR = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.07; 0.81).

DFS-rates for the follow-up times of 1-, 3-, and 5-years were 88.4%, 81.2% and 78.8% in sub-cohort I as compared to 79.0%, 74.2% and 69.6% in sub-cohort II (Table 1), indicating no significant differences (p = 0.364, log-rank-test; p = 0.916, multivariate Cox model adjusted for gender and tumor localization; HR = 0.968, 95% CI: 0.534, 1.756). Regarding tumor size ≥10 cm (p = 0.014, HR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.14;0.90), mitotic rate ≥10/50 HPF (p = 0.011; HR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.12; 0.92) and high-risk classification (p = 0.011; HR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.22; 0.89) DFS was more favourable in “young” GIST patients (detailed data regarding log-rank test and OR at five years see Additional file 1: Table S3).

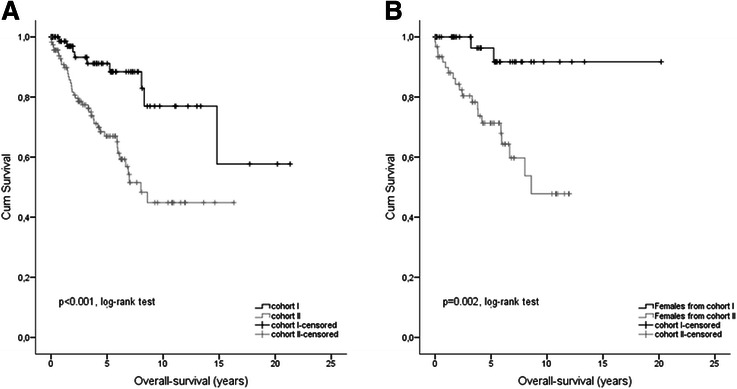

OS-rates were compared after 1-, 3- and 5-year follow up between sub-cohort I (98.5%, 93.2% and 91.2%) and sub-cohort II (90.8%, 77.4% and 67.0%, Table 1). Again GIST patients younger than 50 years showed a more favourable outcome which was significantly different (p <0.001; HR = 0.292, 95% CI: 0.140; 0.606, Figure 4A). Regarding gender aspects again female patients particularly with an age <50 years showed better OS (p = 0.002, log-rank test; p = 0.008, cox model; HR = 0.141, 95% CI: 0.033; 0.604, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Age and gender related outcome regarding OS. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) for GIST patients of study cohort I (<50 years at diagnosis) versus study cohort II (≥50 years at diagnosis). (B) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) for female GIST patients of study cohort I (<50 years at diagnosis) versus study cohort II (≥50 years at diagnosis).

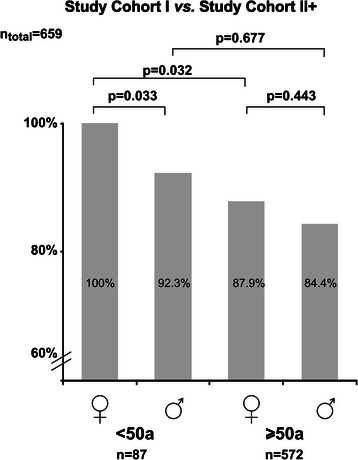

To replicate the association of clinical outcome data regarding age and gender we used study cohort II+ which included 572 GIST patients of the Ulmer GIST registry older than 50 years (Figure 1). The descriptive and clinical data if provided for cohort II+ (Additional file 1: Table S4) were not different compared to cohort II “old” (Table 1). However, the median follow-up time of cohort II+ was 3.25 years (range 0.01; 21.33) and approximately one year shorter compared with cohort II (4.57 years, range 0.56; 21.33). As shown by Figure 5 more favourable outcome was found again for young female GIST patients (<50 years) comparing DSS-rates after a 5 year follow-up (p = 0.032, log-rank test).

Figure 5.

Summary of unadjusted p -values for disease-specific survival (DSS) of male and female GIST patients of study cohort I (<50 years at diagnosis, n = 87) versus study cohort II+ (≥50 years at diagnosis, n = 572) after 5 year follow-up.

Discussion

The frequencies of GIST in men (54%) and women (46%) [6] are quite similar. About three quarters of GIST are diagnosed in patients aged above 50 years (median 58 years [25]). In population based series including cases diagnosed at autopsy, the median age was approximately ten years older (66 to 69 years) [5,7]. Combined data on age and gender related to clinicopathological findings of GIST and/or prognosis are limited. This may be of importance since gender-related effects (e.g. hormonal status) in younger GIST patients may contribute to GIST prognosis.

Here, we present an observational study, evaluating comprehensively clinicopathological features of GIST and patient outcome to elucidate more deeply the role of patient’s age and gender on the prognosis of GIST. We analyzed 87 GIST patients younger than fifty years (sub-cohort I) and compared these study cohort with data from a single-center collective of patients older than 50 years (n = 125, sub-cohort II). Both collectives are part of the multicentre Ulmer GIST registry, encompassing a total of 659 GIST patients at the time of study evaluation.

First, our data demonstrate that generally the distribution of gender, tumor localization, histotype, KIT status, mitotic rate, median tumor size and risk classification by different risk scores are similar between patients younger or older than 50 years at time of diagnosis, in concordance with data of large series of GIST patients [10,15]. More detailed analyses however revealed a significant higher occurrence of small sized GIST (<1 cm) in patients ≥50 years (sub-cohort II, p = 0.002, OR = 11.2, 95%CI: 1.5; 87.0, Table 2). This might be explained by the fact that diagnostic (e.g. endoscopies, radiological scans etc.) as well as surgical procedures are more frequently performed in this age group with a higher frequency of GIST diagnoses as an incidental finding. Autopsy data also support this assumption indicating that 10 to 35% of histologically investigated stomach tissues contain GIST-tumorlets (micro-GIST [26-28]. As expected, elderly patients (sub-cohort II) showed a significantly higher percentage of secondary malignancies (38.8% vs. 15,5%, p < 0.001, OR = 3.5 [1.6; 7.2]). Generally, the occurrence of secondary neoplasia in both GIST cohorts (sub-cohort I plus II) with 29.9% are comparable to published data, reporting secondary malignancies between 14% and 42% of GIST patients [29-31].

The first most striking result of our study is a significantly more favorable DSS rate after 5 year follow up for patients younger than 50 years in comparison to older patients (p = 0.015, log-rank-test; Figure 2) although patients ≥50 years showed significantly more often smaller tumors (<1 cm). The beneficial prognostic effect held true for OS (p < 0.001, log-rank-test; Figure 4B) in younger patients but was not seen regarding DFS (p = 0.364). Our data are supported by Tran et al. [6] who reported that older age (>65 years) was an independent predictor of mortality (OS) in GIST patients. In contrast a study including 188 patients showed that younger age (<50 yrs) was associated with worse prognosis in GIST (p = 0.035), highlighting a putative beneficial prognostic value of older age in GIST [24]. Reasons for this discrepancy may be due to the limited number of patients in the study by Cao et al. as well as the clinical endpoint OS used by the authors. Since, about 50% of death in GIST patients are not GIST-related, supported by our data, DSS may be a more appropriate clinical endpoint in GIST for outcome analyses.

The second interesting result of our study was a gender-related difference in patient outcome. Only younger women showed better DSS (p = 0.008, Figure 3A) and this effect held true after comparison of young female vs. male GIST patients in cohort I (p = 0.033, Figure 3B). To exclude confounding by the use of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor Imatinib, Kaplan-Meier analyses for DSS were recalculated by censoring all patients who received TKI treatment, resulting again in a more favourable prognosis of young females (p = 0.047). These results are in accordance with data from Miettinen et al. who reported an excellent long-term-prognosis particularly in female patients younger than 21 years and gastric GIST [13]. In addition, male gender was associated by some authors with a more worse outcome [32,33].

The underlying mechanism for the gender-related more favorable prognosis of GIST in patients younger than <50 years remains unclear. There may be a relationship to the reproductive age in younger females or to the use of contraceptive medication but this is speculative and several confounding factors need to be considered.

Young females are significantly overrepresented among gastric GIST patients aged <40 years (>80%) [34-38]. Current knowledge confirms that the majority of GIST in young adults as well as in children, particularly female patients, representing a distinctive disease entity different from the kinase mutated GIST in adults (so-called type 1 GIST). This subtype of GIST harbors molecular alterations in the mitochondrial enzymatic cascade succinate dehydrogenase (SDH). Mutations in any of the four SDH subunits (A,B,C,D), either germline or somatic, result in complete loss of the nuclear expression of the subunit B shown by results of immunohistochemistry (SDHB-deficient or type 2 GIST) [34-41]. Patients with germline mutations in SDHB may develop both GIST and paraganglioma (= Carney-Stratakis syndrome) [42]. On the other hand, patients with the non-hereditary Carney triad (GIST, pulmonary chondroma and paraganglioma) lack mutations in the SDH complex. Instead, epigenetic silencing of the SDH subunit C by DNA methylation as a novel non-heritable mechanism for the development of Carney triad-associated GIST may be more important [43]. Common to the heterogeneous type 2 GISTs are the early age of onset of disease before 40 years and a striking female predilection of >80% except SDH subunit A mutated cases which occur at relatively higher age and affect both genders. Thus, regarding the prognostic impact of age and gender, some of the young females of our study cohort might have had type 2 GIST. Nevertheless, given the low prevalence of SDHB-deficient GIST of about 7% among gastric GIST [36], it appears to be unlikely that a predominance of type 2 GIST may explain entirely the age group effect of our study.

Conclusions

In summary, we present first data on the prognostic impact of age and gender in patients with GIST. The favourable outcome in the young age group which is gender-specific remains currently poorly understood. The real impact of age- and gender-related biological and pathophysiological factors on the prognosis in GIST warrants further prospective studies on larger cohorts with matched genotype and tumor site.

Acknowledgement

We do thank Annette Blatz (University of Ulm, Germany) for editorial assistance and Karl and Annemarie Schmieder (Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany) for data management. MS was in part supported by the Robert Bosch Stiftung, Stuttgart, Germany and the IZEPHA grant Tübingen-Stuttgart #8-0-0.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- DFS

Disease-free-survival

- DSS

Disease-specific-survival

- E.g.

“Exempli gratia” (for example)

- GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- HPF

High power field

- I.e.

Id est

- NF

Neurofibromatosis

- OR

Odds ratio

- PDGFRα

Platlet-derived growth factor alpha

- SD

Standard deviation

- SEER

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results

- STROBE

Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- Yr

Year(s)

Additional file

Intercollective analysis: Summary of Kaplan-Meier-analyses for disease-specific survival (DSS) and disease-free survival (DFS) after 5 year follow up of 5 years in GIST patients of study-cohort I (< 50 year) versus study-cohort II (≥50 year).0020. Table S2. Intracollective analysis: Summary of Kaplan-Meier-analyses for disease-specific survival (DSS) and disease-free survival (DFS) after 5 year follow up in GIST patients within study-cohort I (<50 years) and study cohort II (≥50 year). Table S3. Disease-free survival (DFS) for GIST patients <50 years (sub-cohort I “young”) versus ≥50 years (sub-cohort II “old”) related to GIST relevant clinicopathological parameters.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The contributions of each author to the manuscript are: KK and MiSc conceived and designed the study. KK, KB, HS, and MiSc were involved in the data aquisition. KK, BM, MaSc, AA, DHB, UK, and MiSc contributed to data analysis and interpretation. KK, MaSc, AA and MiSc contributed to the writing of the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Klaus Kramer, Email: klaus.kramer@uniklinik-ulm.de.

Uwe Knippschild, Email: uwe.knippschild@uniklinik-ulm.de.

Benjamin Mayer, Email: benjamin.mayer@uni-ulm.de.

Kira Bögelspacher, k.boegelspacher@googlemail.com.

Hanno Spatz, Email: hannospatz@hotmail.com.

Doris Henne-Bruns, Email: doris.henne-bruns@uniklinik-ulm.de.

Abbas Agaimy, Email: abbas.agaimy@uk-erlangen.de.

Matthias Schwab, Email: matthias.schwab@ikp-stuttgart.de.

Michael Schmieder, Email: GISTUlm@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(80):577–80. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin BP, Antonescu CR, Scott-Browne JP, Comstock ML, Gu Y, Tanas MR, et al. A knock-in mouse model of gastrointestinal stromal tumor harboring kit K641E. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6631–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommer G, Agosti V, Ehlers I, Rossi F, Corbacioglu S, Farkas J, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in a mouse model by targeted mutation of the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037763100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Odén A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era–a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran T, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of 1,458 cases from 1992 to 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:162–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tryggvason G, Kristmundsson T, Orvar K, Jónasson JG, Magnússon MK, Gíslason HG. Clinical study on gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) in Iceland, 1990–2003. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2249–53. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzen C-Y, Wang J-H, Huang Y-J, Wang M-N, Lin P-C, Lai G-L, et al. Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a retrospective study based on immunohistochemical and mutational analyses. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:792–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9480-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steigen SE, Eide TJ. Trends in incidence and survival of mesenchymal neoplasm of the digestive tract within a defined population of northern Norway. APMIS. 2006;114:192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodall CE, Brock GN, Fan J, Byam JA, Scoggins CR, McMasters KM, et al. An evaluation of 2537 gastrointestinal stromal tumors for a proposed clinical staging system. Arch Surg. 2009;144:670–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miettinen M, Makhlouf H, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the jejunum and ileum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 906 cases before imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:477–89. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaemmer DA, Otto J, Lassay L, Steinau G, Klink C, Junge K, et al. The Gist of literature on pediatric GIST: review of clinical presentation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:108–12. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181923cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miettinen M, Lasota J, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach in children and young adults: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 44 cases with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1373–81. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000172190.79552.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prakash S, Sarran L, Socci N, DeMatteo RP, Eisenstat J, Greco AM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in children and young adults. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:179–87. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000157790.81329.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:52–68. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146010.92933.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer K. Establishment of a multi-centric GIST registry and oncologic network. University of Ulm: Master’s Thesis; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. 2nd edition. Volume 2nd Editio. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–35. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:W163–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blay J-Y, Wardelmann E. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7(Supplement 7)):vii49–55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher CDM, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459–65. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao H, Zhang Y, Wang M, Shen D, Sheng Z, Ni X, et al. Prognostic analysis of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a single unit experience with surgical treatment of primary disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Matteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agaimy A, Wünsch PH, Hofstaedter F, Blaszyk H, Rümmele P, Gaumann A, et al. Minute gastric sclerosing stromal tumors (GIST tumorlets) are common in adults and frequently show c-KIT mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:113–20. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213307.05811.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, Hishima T, Iwasaki Y, Saito K, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steigen SE, Bjerkehagen B, Haugland HK, Nordrum IS, Løberg EM, Isaksen V, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic markers for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Norway. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:46–53. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agaimy A, Wünsch PH, Sobin LH, Lasota J, Miettinen M. Occurrence of other malignancies in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:120–9. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandurengan RK, Dumont AG, Araujo DM, Ludwig JA, Ravi V, Patel S, et al. Survival of patients with multiple primary malignancies: a study of 783 patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2107–11. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vassos N, Agaimy A, Hohenberger W, Croner RS. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) and malignant neoplasms of different origin: Prognostic implications. Int J Surg. 2014;12(5):371–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer S, Rubin BP, Lux ML, Chen C-J, Demetri GD, Fletcher CDM, et al. Prognostic value of KIT mutation type, mitotic activity, and histologic subtype in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3898–905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimoto Y, Nakanishi Y, Yoshimura K, Shimoda T. Clinicopathologic study of primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach, with special reference to prognostic factors: analysis of results in 140 surgically resected patients. Gastric Cancer. 2003;6:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s101200300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dwight T, Benn DE, Clarkson A, Vilain R, Lipton L, Robinson BG, et al. Loss of SDHA expression identifies SDHA mutations in succinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:226–33. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182671155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Succinate dehydrogenase deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) - a review. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53C:514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, McCue P, Czapiewski P, Langfort R, Waloszczyk P, et al. Mapping of succinate dehydrogenase losses in 2258 epithelial neoplasms. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2014;22:31–6. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31828bfdd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miettinen M, Wang Z-F, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Osuch C, Rutkowski P, Lasota J. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient GISTs: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 66 gastric GISTs with predilection to young age. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1712–21. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182260752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wardelmann E. Translational research and diagnosis in GIST. Pathologe. 2012;33(Suppl 2):273–7. doi: 10.1007/s00292-012-1682-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Italiano A, Chen C-L, Sung Y-S, Singer S, DeMatteo RP, LaQuaglia MP, et al. SDHA loss of function mutations in a subset of young adult wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:408. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miettinen M, Killian JK, Wang Z-F, Lasota J, Lau C, Jones L, et al. Immunohistochemical loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) signals SDHA germline mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:234–40. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182671178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner AJ, Remillard SP, Zhang Y-X, Doyle LA, George S, Hornick JL. Loss of expression of SDHA predicts SDHA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:289–94. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janeway KA, Kim SY, Lodish M, Nosé V, Rustin P, Gaal J, et al. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:314–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haller F, Moskalev EA, Faucz FR, Barthelmeß S, Wiemann S, Bieg M, et al. Aberrant DNA hypermethylation of SDHC: a novel mechanism of tumor development in Carney triad. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:567–77. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]