Abstract

A solution-phase perfluoroalkylation of C60 with a series of RFI reagents was studied. The effects of molar ratio of the reagents, reaction time, and presence of copper metal promoter on fullerene conversion and product composition were evaluated. Ten aliphatic and aromatic RFI reagents were investigated (CF3I, C2F5I, n-C3F7I, i-C3F7I, n-C4F9I, (CF3)(C2F5)CFI, n-C8F17I, C6F5CF2I, C6F5I, and 1,3-(CF3)2C6F3I) and eight of them (except for C6F5I and 1,3-(CF3)2C6F3I) were found to add the respective RF groups to C60 in solution. Efficient and selective synthesis of C60(RF)2 derivatives was developed.

Keywords: fullerene, C60, perfluoroalkylation, RFI, perfluoroalkyl radicals

1. Introduction

The chemistry of perfluoroalkylfullerenes (PFAFs) has been rapidly evolving in recent years. Many isomerically-pure derivatives of C60,[1–5] C70,[6–9] hollow higher fullerenes,[10–13] and endometallofullerenes[14–16] have been synthesized, isolated, and studied by various techniques. Perfluoroalkylfullerenes were shown to be attractive electron acceptors due to their high thermal and chemical stability, reversible electrochemical behavior in solution, and a broad range of their first reduction potentials.[1,8,17] It was also shown that PFAFs can be further derivatized chemically to form donor-acceptor diads and potentially other complex molecular systems.[18,19] The vast majority of PFAF syntheses described in the literature relied on heterogeneous high-temperature reactions between fullerenes and RF· precursors (e.g., RFI or AgOOCCF3, see refs. above). Such conditions typically favor the formation of PFAFs with a large number of RF substituents, with simple bis-derivatives fullerene(RF)2 either absent from crude reaction mixtures or present in trace amounts.[4,5,20,21] Only 1,7-C60(CF3)2,[20,22] 1,7-C60(C2F5)2,[23] and 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2[24] have been isolated and characterized using high-temperature heterogeneous synthetic methods. It is notable that previous studies of C60 halogenation demonstrated that selective synthesis of simple bis-derivatives C60Hal2 (Hal = F, Cl, and Br; iodofullerenes have not been reported) is difficult to achieve while many multisubstituted C60Haln have been prepared (e.g., C60F18, C60F36, C60F48, C60Cl6, C60Cl24, and C60Br24). For example, single isomers of C60F2[25] and C60Cl2[26] were only prepared as minor products; C60Br2 has never been observed experimentally.

Recently we reported a fundamental study of substituent effects in a series of 1,7-C60(RF)2 compounds with RF = CF3, C2F5, n-C3F7, i-C3F7, n-C4F9, s-C4F9 (secondary-CF(CF3)(C2F5)), and n-C8F17 using cyclic voltammetry, low-temperature anion photoelectron spectroscopy, and DFT calculations.[23] The similarity of the first reduction potentials of these compounds, their largely intact π-systems, and differences in their physical properties (e.g., different solubility[23] and crystal packing[23,24,27]) makes them an intriguing series of compounds that may be used to study the effects of morphology of the active polymer-fullerene blend layers on the function of microelectronic devices such as solar cells. Except for 1,7-C60(RF)2 compounds with RF = CF3 and C2F5, all other 1,7-C60(RF)2 compounds in that study were prepared using a solution-phase perfluoroalkylation technique.[23] In this paper we report the development and optimization of this synthetic method.

Krusic and co-workers were the first to explore a solution-phase fullerene perfluoroalkylation in 1991.[28] They observed the formation of C60(CF3)· radical by ESR spectroscopy in a reaction of C60 with (CF3CO2)2 under UV irradiation in Freon-113.[28] In 1993 Fagan, Krusic, and co-workers described fullerene perfluoroalkylation with several RF radical sources (CF3I, C2F5I, n-C3F7I, n-C6F13I, (CF3CO2)2, (C2F5CO2)2, and (n-C3F7CO2)2) in various solvents (1,2,4-trichlorobenzene, benzene, hexafluorobenzene, tert-butylbenzene, and chlorobenzene) at elevated temperatures or under UV irradiation.[29] Complex mixtures of C60,70(RF)nHm products with n up to 16 and m up to 30 have been prepared but no single isomers were isolated.[29] Several papers described ESR studies of various C60(RF)· and C70(RF)· species formed in solutions of aromatic and aliphatic solvents (benzene, toluene, tert-butylbenzene, and methylcyclohexane) from corresponding bare-cage fullerenes and various RF radical precursors (RFI, RFBr, and (RFCO2)2) at elevated temperatures or under UV irradiation.[30–33] In 1993 Yoshida and co-workers reported that a reaction of C60 with (RFCO2)2 (RF = CF3 and n-C3F7) in deoxygenated chlorobenzene solution at 40 °C resulted in formation of 1,7-C60RF(OH) alcohol and 1,9-C60O2CRF(OH) “orthoester” (CRF(OH) moiety connected to C60 via two oxygen atoms forming a 1,3-dioxolane cycle).[34] Interestingly, in 1994 the same group reported a reduction of (C60RF)2 dimer by Bu3SnH to form C60RFH;[35] they claimed that the dimer was prepared and reported in their 1993 paper using the solution-phase reaction of C60 with [RFCO2]2 (the dimer formation or isolation was not mentioned in that paper).[34] In 1999 Yoshida and co-workers reported an optimized procedure for (C60RF)2 synthesis based on a reaction of C60 with RFI (RF = n-C3F7, n-C4F9, n-C6F13) in 1,2-dichlorobenzene (ODCB) solution in the presence of hexabutylditin or hexamethylditin under irradiation with metal-halide lamp.[36] A solution-phase synthesis of a mixture of perfluorohexylated species with an average composition C60(C6F13)~5 in a reaction of C60 with n-C6F13I in 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene at 200 °C was reported in 1999, but the elemental analysis was the only characterization method used in that study.[37]

In this work we studied the solution-phase perfluoroalkylation of C60 in detail using HPLC analysis and mass spectrometry with the aim of selective and efficient preparation of C60(RF)2 derivatives and other PFAFs. Multiple small-scale experiments were carried out in order to ascertain the effects of the molar ratio of the reagents, reaction time, and copper metal promoter on the product composition and C60 conversion.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Solvents and Reagents

The solvents toluene (Fisher Scientific; HPLC grade), n-heptane (Fisher Scientific; HPLC grade), acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific; HPLC grade), dimethyl sulfoxide (Fisher Scientific; ACS grade), 1,2-dichlorobenzene (ODCB; Acros Organics; ACS grade), chloroform-d (99.8% D, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) were used as received. The compounds C60 (99.9%, Term-USA), RFI (RF = CF3, C2F5, n-C3F7, i-C3F7, n-C4F9, s-C4F9, n-C8F17, CF2C6F5, C6F5, 3,5-(CF3)2C6F3) (SynQuest Labs), and copper powder (Fisher Scientific; 325 mesh; electrolytic grade) were used as received.

2.2. Instruments

HPLC analysis and separation was accomplished using Shimadzu HPLC instrumentation (CBM-20A control module, SPD-20A UV-detector set to 300 nm detection, LC-6AD pump, manual injector valve) equipped with a 10-mm I.D. × 250 mm semipreparative Cosmosil Buckyprep column (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) Atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) mass spectra were recorded using Agilent Technologies Model 6210 TOF spectrometer with APCI source. The carrier solvent was acetonitrile with 1% toluene; PFAF samples were injected as toluene solutions. Fluorine-19 NMR spectra were recorded on Varian 400 MR spectrometer at 376 MHz frequency (CDCl3 solvent was used).

2.3. Perfluoroalkylation experiments

Aliquots of 500 μL of a stock solution of C60 in ODCB (13.8 mM) was transferred into a Pyrex glass ampoule (O.D. = 8.0 mm; I.D. = 5.0 mm; L = 140 mm; V = 2.7 mL) containing ca. 500 mg of copper powder. An RFI reagent was then added via a gas-tight syringe (for small excesses of 6 equivalents a diluted stock solution of i-C3F7I in ODCB was used), and the solution was diluted to 1.0 mL with pure ODCB (in several experiments 250 μL of DMSO were also added prior to the ODCB dilution). The gaseous reagents CF3I (b.p. = −21.85 °C[38]) and C2F5I (b.p. = 12.5 °C, vendor data) were measured volumetrically and transferred on a vacuum line equipped with a calibrated volume and an electronic manometer (MKS Instruments Baratron vacuum gauge, 0–1.3 bar). In these two cases the 500 μL stock solution of C60 was diluted to 1.0 mL volume with ODCB prior to the addition of CF3I and C2F5I. In all cases the ampoules were degassed three times using a freeze-pump-thaw technique, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and flame-sealed under vacuum. The ampoules were heated at 180 °C in a tube furnace, then cooled down, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and opened. The crude reaction mixtures were evaporated under vacuum to dryness (reaction mixtures containing DMSO were washed with water three times prior to drying). The dry residues were dissolved in 10.0 mL of toluene, filtered, and analyzed using HPLC (100 μL sample injections) and APCI mass spectrometry.

3. Results

The effects of the reaction time and the molar ratio of the reagents on C60 conversion and product distribution were studied using reactions between C60 and i-C3F7I. The reaction conditions were kept the same except for varying amounts of i-C3F7I (6, 18, 54, and 162 equivalents) and reaction time (1 and 3 days). In all cases reactions were carried out in degassed 1,2-dichlorobenzene (ODCB) solution at 180 °C in sealed glass ampoules of the same volume (2.7 mL). A large excess of copper metal powder (500 mg; 7.9 mmol) was added to each of the reaction mixtures prior to degassing and heating. In all solution-phase experiments described in this work the total volume of the reaction mixture was 1.0 mL and the initial concentration of C60 was 6.9 mM. The crude reaction mixtures were filtered, evaporated to dryness, and dissolved in 10.0 mL of toluene. These solutions were analyzed by HPLC using pure toluene as the primary eluent and the HPLC traces were stacked for direct comparison, see Figure 1 (injection volume was 100 μL; retention time tR(C60) = 8.7 min; tR(1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2) = 5.7 min[23]). Pure toluene was not effective for the analysis of C60(i-C3F7)n>4 products due to their short retention times; for such mixtures pure heptane was used instead to provide adequate peak separation (see inserts in Figure 1). The crude products were also analyzed by negative-ion APCI mass spectrometry which showed distributions of peaks corresponding to the C60(C3F7)n− anions with n = 1–8. The numbers shown to the immediate right of the HPLC traces on Figure 1 represent the distributions of the C60(C3F7)n− peaks observed in the NI-APCI mass spectra of the corresponding products (the large-font numbers represent the most intense peaks in the spectra). It is notable that no evidence of the formation of dimeric species (C60RF)2 were observed throughout our study (neither by mass spectrometry nor by HPLC analysis).[34–36]

Figure 1.

The HPLC analysis of several C60 + N(i-C3F7I) reactions carried out in o-DCB solution in the presence of copper powder at 180 °C. The peaks at tR = 5.7 minutes marked with daggers corresponds to 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2; the peaks at tR = 8.7 minutes marked with stars correspond to unreacted C60. The numbers on the right-hand side of the HPLC traces show the distribution of C60(C3F7)n− anions observed in the NI-APCI MS analysis of the corresponding samples (the numbers given with a large font correspond to the most intense ion in the spectra). The inserts show the HPLC traces of four samples acquired using 100% heptane eluent.

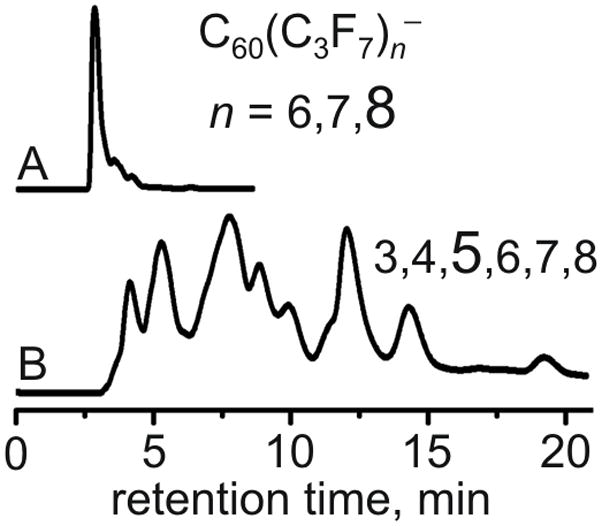

The effect of the copper metal was studied in a separate experiment. A sample of C60 was allowed to react with 162 equivalents of i-C3F7I in ODCB solution at 180 °C for 3 days without any copper present. Upon the workup the reaction mixture was found to contain a significant amount of iodine (no iodine was observed in any of the reactions carried out in the presence of copper). The product was analyzed by HPLC and NI-APCI mass spectrometry; the composition of the PFAF products formed in a three-day reaction between C60 and 162 equivalents of i-C3F7I without copper is similar to the products formed in one-day reaction of C60 and 54 equivalents of i-C3F7I with copper (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

HPLC and NI-APCI mass spectrometry analysis of the products of the reaction of C60 with 162 equivalents of i-C3F7I reagent in ODCB solution at 180 °C for three days with copper metal powder (A) and without copper metal powder (B). The n values represent the distributions of C60(C3F7)n− species observed in the NI-APCI mass spectra.

Several reactions between C60 and 54 and 18 equivalents of CF3I and 18 equivalents of i-C3F7I were also carried in 25/75 v/v DMSO/ODCB mixture at 180 °C, both with and without copper metal. The crude reaction mixtures were washed with water several times to remove DMSO; then they were treated analogously to the crude products prepared in pure ODCB. The resulting products quickly decomposed upon their exposure to air (the freshly filtered solutions quickly changed color and became murky with white insoluble precipitates) which made them impossible to analyze using conventional HPLC or mass spectrometry.

The reactivity of different RFI reagents (RF = CF3, C2F5, n-C3F7, i-C3F7, n-C4F9, s-C4F9, n-C8F17, CF2C6F5, C6F5, and 3,5-(CF3)2C6F3) toward C60 in ODCB solution was also studied; 18 equivalents of the RFI reagents were used in all cases and the reaction time was one day. The resulting reaction mixtures were studied by HPLC using pure toluene as the eluent, see Figure 3 (50/50 v/v toluene/heptane mixture was also used for the perfluorobenzylated products, see the insert in Figure 3). The aliphatic RFIs and perfluorobenzyl iodide yielded the corresponding C60(RF)n products (this was confirmed by NI-APCI mass spectrometry, figures not shown). No reaction was observed for the aromatic RFI reagents C6F5I and 3,5-(CF3)2C6F3I.

Figure 3.

HPLC analysis of the products of C60 reactions with 18 equivalents of various RFI reagents. Reactions were carried out in ODCB solution in the presence of copper powder at 180 °C for one day.

It is notable that most of the C60 reagent precipitated out of the hot ODCB after several hours of heating when CF3I, 3,5-(CF3)2C6F3I, or C6F5I were used. In these cases the hot ODCB solutions changed from a deep magenta to a pale-pink color and black precipitates were formed. After cooling the black precipitates were redissolved forming the deep magenta-colored solutions typical of C60 (the HPLC analysis also confirmed that the C60 reagent was unchanged, see Figure 3). These observed precipitations are consistent with the experimentally studied anomalous temperature dependence of C60 solubility in organic solvents including ODCB.[39,40]

Finally, we performed several experiments with ca. 0.027 bar of gaseous C2F5I, n-C3F7I, and i-C3F7I and C60 in a GTGS reactor.[22] The reaction between C2F5I and C60 without copper metal at ca. 480 °C was largely unsuccessful due to a very low C60 conversion (less than 5%).[23] In order to improve the conversion of C60 we performed an experiment with the use of Cu powder as a promoter but it led to a high abundance of C60(C2F5)n products with n > 2 (P(C2F5I) = 0.021–0.016 bar; T = 430 °C; the yield of 1,7-C60(C2F5)2 was ca. 1–2 mol%; see Supporting Information of ref. [23]). Attempts to use a GTGS reactor to carry out reactions with n-C3F7I and i-C3F7I did not yield any PFAF products, and all starting C60 was recovered unchanged both with and without copper metal powder; a range of the reaction temperatures up to 500 °C was explored.

4. Discussion

Reactions involving perfluoroalkyl radicals are commonly used for a preparation of a variety of organofluorine compounds.[41] Substitution of aromatic hydrogen atoms by RF· radicals has been used to prepare aromatic compounds bearing various RF groups[42–46] (see also [47,48] for similar catalytic processes); addition of RF· radicals to alkenes has also been well-studied.[49,50] Thermolysis of RFI or (RFCO2)2 precursors has been commonly used to generate RF· radicals (see for example [42,43,46]). The other common method of RF· generation relies on a rapid reaction of RFI with CH3· or C6H5· radicals formed in situ (in the reaction of acetone with hydrogen peroxide[44] or by photolysis of (PhCO2)2[45,51], correspondingly).

The original work by Fagan and co-workers[29] was the first to employ the addition of perfluoroalkyl radicals to fullerenes leading to a successful synthesis of mixtures of various perfluoroalkylated fullerenes (PFAFs). In that work, RF· radicals were formed in situ by thermolysis or UV irradiation of solutions of RFI or (RFCO2)2 radical precursors; RF· then reacted with C60 (or C70) which acted as a radical trap.[29,37] The formation of radical intermediates C60(RF)· was confirmed by ESR spectroscopy.[29–33] Large excess of RF· radical precursors were used, resulting in mixtures of highly perfluoroalkylated PFAFs. It is notable that the use of C6H6 reaction medium resulted in the formation of some hydrogenated PFAFs.[29] This process was eliminated by the use of fluorinated solvents such as C6F6 or Freon-113,[29] but these reactions must have been heterogeneous since fullerenes are practically insoluble in fluorinated solvents.[52]

In this study, thermolysis of RFI reagents was chosen for the generation of RF· radicals in order to avoid possible side-reactions of radicals other than RF· with C60 (e.g., CH3· or C6H5· radicals[44,45,51]). Note that C60In compounds with covalent C60-I bonds have not been reported; this is believed to be due to the low energy of C60-I bonds.[53] In this work we have not observed any evidence for the formation of persistent C60(RF)nIm species.

The reaction medium was chosen to be 1,2-dichlorobenzene (ODCB) due to several factors. First, C60 and other fullerenes and fullerene derivatives are known to be very soluble in ODCB[52] (anomalous temperature dependence of fullerene solubility notwithstanding[39,40]). Second, ODCB has a high boiling point (180 °C) and a relatively low vapor pressure which eliminates the need for high-pressure reactors. Third, it is rather inert toward radical reactions; we have not observed appreciable amounts of fullerene products with substituents other than RFs (e.g., hydrogen atoms[29] or aryl groups) or products resulting from a perfluoroalkylation of ODCB. The higher-boiling 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene was also considered, but it is harder to remove under vacuum which complicates workup of the crude products.

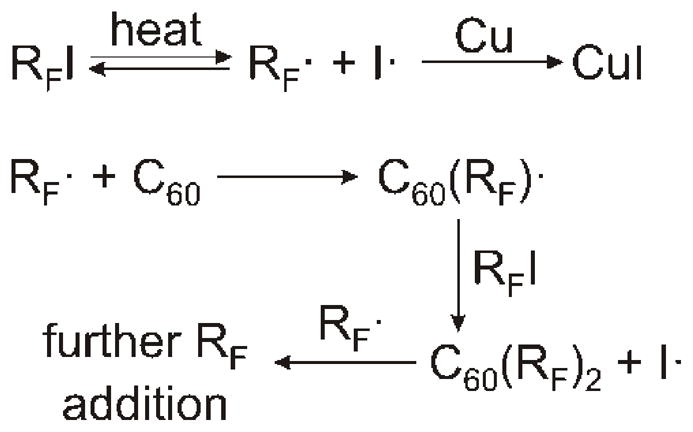

Copper metal powder was used to promote the decomposition of RFI reagents and accelerate fullerene perfluoroalkylation in solution. It was found that C60 perfluoroalkylation also takes place without copper metal but the reaction rate was several times slower. Copper metal serves as an iodine scavenger,[22] thereby shifting the equilibrium of RFI dissociation toward the formation of the RF radicals, see Scheme 1. Even with copper metal present, the decomposition of the RFI reagents at 180 ·C is relatively slow, which necessitated the use of high stoichoimetric ratios of the reagents (n(RFI)/n(C60) up to 162 equivalents for some reactions with i-C3F7I). It is likely that other metals like Ag and Tl can also be used as iodine scavengers. We have not tested these metals in this work due to their higher price and high toxicity.

Scheme 1.

Fullerene perfluoroalkylation in solution (possible chain termination processes and are not shown).

It is notable that high-boiling polar solvents like DMSO, DMF, pyridine, and HMPA have been used extensively for solution-phase coupling reactions between aliphatic and aromatic halogenated substrates and RFI reagents in the presence of copper metal. In such reactions a halogen atom (typically iodine or bromine) is substituted by an RF group.[54–56] These reactions are likely to involve the initial formation of perfluoroorganocopper intermediates [RFCu] (formation of such intermediates was shown in several cases, see refs. above). The use of polar solvents (donor number > 19) is believed to be necessary to minimize the unwanted formation of RF radicals which decreases the selectivity and yield of the coupling reactions.[55] Fullerenes are practically insoluble in polar solvents,[52] so we used 25/75 v/v mixture of DMSO and ODCB to carry out fullerene perfluoroalkylation. Air-sensitive products of unknown compositions were formed, therefore this direction was not pursued further. The fact that C60 perfluoroalkylation by RFI in hot ODCB occurs even without any copper metal present (albeit at a slower rate, see above) suggests that the formation of organocuprate reagents is probably not involved in this reaction which is likely to be a simple radical addition.

The solution-phase reaction of i-C3F7I with C60 in ODCB in the presence of copper showed that molar ratios of these reagents and reaction time have a strong effect on the composition of products, see Figure 1. A low excess of i-C3F7I (6 equivalents) led to a very low C60 conversion after a one-day reaction. Most of the starting C60 was left unchanged but the HPLC analysis and the NI-APCI mass spectrometry showed that a small amount of 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2 was formed (the single isomer of this compound was isolated earlier from the products of heterogeneous C60 perfluoroalkylation, see ref. [23]). A longer reaction time (three days) led to a better C60 conversion and a relatively selective formation of 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2 with a ca. 25% yield (based on the HPLC analysis). The reaction with 18 equivalents of i-C3F7I over a period of one day led to a lower conversion of C60 and a selective formation of 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2 with a ca. 40% yield. The HPLC analysis and the mass spectrometry also showed that only small amounts of C60(i-C3F7)4,6 compounds were formed (highly-substituted C60(RF)n compounds typically have shorter retention times[21,22]). Higher molar ratios of i-C3F7I to C60 and longer reaction time resulted in formation of more highly substituted products. A high excess of i-C3F7I (162 equivalents) used in a three-day reaction, resulted in the formation of a major C60(i-C3F7)8 product as shown by the mass spectrometry. Fluorine-19 NMR spectroscopy of this product suggested it to be a mixture of isomers (figure not shown). This shows that the maximum number of i-C3F7 groups that can be added to C60 under these conditions is limited to eight (Max(i-C3F7/C60) = 8). This lies in agreement with the results of high-temperature heterogeneous reactions between C60 and high-pressure gaseous i-C3F7I that also did not produce any products with more than eight i-C3F7 substituents (but multiple isomers of C60(i-C3F7)4,6,8 were isolated and characterized).[24] The maximum number of RF additions to the C60 cage depends on the steric demand of the RF groups. For the smallest RF group, CF3, C60(CF3)22 species have been observed experimentally (Max(CF3/C60) = 22).[57] As the size of the RF substituents increases, the highest experimentally observed degree of C60 perfluoroalkylation decreases (Max(C2F5/C60) = 16; Max(n-C3F7/C60) = 12; see also ref. [21] for other experimental Max(RF/C60) values).

Reaction conditions that led to a low conversion of C60 produced 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2 with a high degree of selectivity, see Figure 1. In our experiments it corresponded to 6 and 18 equivalents of i-C3F7I (the high excess implies that not all of this reagent is used up productively during the reaction). The mass spectrometry analysis of the corresponding products showed a wide range of C60(i-C3F7)n with up to eight substituents were formed. It is notable that no RF fragmentation was observed in any of the solution-phase reactions described in this work; such fragmentation was observed above 300 °C when longer-chain RFI reagents were used for heterogeneous perfluoroalkylation of fullerenes[21].

Based on this work we developed several efficient solution-phase syntheses of new 1,7-C60(RF)2 compounds with RF = n-C3F7, i-C3F7, n-C4F7, s-C4F7, and n-C8F17 which are described in a separate paper.[23] After some optimization of the reaction conditions and HPLC-based separation procedures these compounds were prepared with 10–20 mol% yields, see ref. [23] for synthetic details and analytical data of the isolated compounds. Higher yields may be achievable; e.g., ca. 40% yield (based on the HPLC trace integration) was achieved in a small-scale synthesis of 1,7-C60(i-C3F7)2, see Figure 1 (N(i-C3F7I) = 18; reaction time = 1 day). In the corresponding large-scale experiments the yields varied between 10–20% depending on small variations of the heating regime and other reaction parameters such as reactor size and geometry;[23] the yields and conversion were kept intentionally low to suppress the formation of C60(RF)n>2 which, unlike unreacted C60, cannot be recycled.

5. Conclusions

The results presented in this work indicate that homogeneous perfluoroalkylation of C60 is currently the most efficient method for preparation of bis-C60(RF)2 derivatives with a variety of different RF groups. Currently it is the only method of synthesis for 1,7-C60(RF)2 with RF = n-C3F7, n-C4F9, s-C4F9, and n-C8F17. Lower reaction temperatures used for solution-phase perfluoroalkylation were found to completely suppress the temperature-induced fragmentation of the longer RF chains (which leads to the unfavorable formation of “mixed” PFAFs with different RF substituents above 300 °C in heterogeneous processes[21]). Solution-phase C60 perfluoroalkylation is also found to be a good method for preparation of fullerene derivatives with the highest sterically possible numbers of RF substituents (such reactions should use a high excess of the RFI reagent and long reaction times). Experimental results showed that many different C60(RF)n products with an “intermediate” number of substituents (2 < n < Max(RF/C60)) are formed using the solution-phase perfluoroalkylation process. HPLC analysis of such mixtures suggests that many of these compounds can be isolated in pure state (although with a low yield). These results show that solution-phase fullerene perfluoroalkylation is a versatile technique suitable for preparation of many PFAFs with varying number of perfluorinated aliphatic or benzylic RF groups.

Highlights.

Efficient perfluoroalkylation of C60 with RFI reagents under homogeneous conditions.

Strong effect of reagent ratio, reaction time, and copper promoter on product composition

Selective synthesis of bis-adducts is based on “low-conversion” reaction regime

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U. S. National Science Foundation (CHE-1012468), NIH (1R21CA140080-1A1) and the Colorado State University Research Foundation. We would like to thank the reviewers of this paper for their very thorough reading and many excellent comments that helped us to significantly improve this paper.

Footnotes

Dedicated to David O’Hagan on the occasion of his receiving ACS Award for Creative work in Fluorine Chemistry

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Igor V. Kuvychko, Email: kuvychko@lamar.colostate.edu.

Steven H. Strauss, Email: steven.strauss@colostate.edu.

Olga V. Boltalina, Email: olga.boltalina@colostate.edu.

References

- 1.Popov AA, Kareev IE, Shustova NB, Stukalin EB, Lebedkin SF, Seppelt K, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV, Dunsch L. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11551–11568. doi: 10.1021/ja073181e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goryunkov AA, Kuvychko IV, Ioffe IN, Dick DL, Sidorov LN, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. J Fluorine Chem. 2003;124:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kareev IE, Kuvychko IV, Lebedkin SF, Miller SM, Anderson OP, Seppelt K, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8362–8375. doi: 10.1021/ja050305j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kareev IE, Kuvychko IV, Lebedkin SF, Miller SM, Anderson OP, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. Chem Commun. 2006:308–310. doi: 10.1039/b513477c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kareev IE, Shustova NB, Kuvychko IV, Lebedkin SF, Miller SM, Anderson OP, Popov AA, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12268–12280. doi: 10.1021/ja063907r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutig T, Kemnitz E, Troyanov SI. J Fluorine Chem. 2010;131:861–866. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ignat’eva DV, Mutig T, Goryunkov AA, Tamm NB, Kemnitz E, Troyanov SI, Sidorov LN. Russ Chem Bull. 2009;58:1146–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popov AA, Kareev IE, Shustova NB, Lebedkin SF, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV, Dunsch L. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:107–121. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorozhkin EI, Ignat’eva DV, Tamm NB, Goryunkov AA, Khavrel PA, Ioffe IN, Popov AA, Kuvychko IV, Streletskiy AV, Markov VY, Spandl J, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:3876–3889. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamm NB, Sidorov LN, Kemnitz E, Troyanov SI. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:10486–10492. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamm NB, Sidorov LN, Kemnitz E, Troyanov SI. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9102–9104. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kareev IE, Kuvychko IV, Shustova NB, Lebedkin SF, Bubnov VP, Anderson OP, Popov AA, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6204–6207. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kareev IE, Popov AA, Kuvychko IV, Shustova NB, Lebedkin SF, Bubnov VP, Anderson OP, Seppelt K, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13471–13489. doi: 10.1021/ja8041614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kareev IE, Lebedkin SF, Bubnov VP, Yagubskii EB, Ioffe IN, Khavrel PA, Kuvychko IV, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:1846–1849. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shustova NB, Peryshkov DV, Kuvychko IV, Chen YS, Mackey MA, Coumbe C, Heaps DT, Confait BS, Heine T, Phillips JP, Stevenson S, Dunsch L, Popov AA, Strauss Steven H, Boltalina OV. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;133:2672–2690. doi: 10.1021/ja109462j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Chen C, Jiao M, Tamm NB, Lanskikh MA, Kemnitz E, Troyanov SI. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:3766–3771. doi: 10.1021/ic200174u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popov AA, Shustova NB, Svitova AL, Mackey MA, Coumbe CE, Phillips JP, Stevenson S, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV, Dunsch L. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:4721–4724. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takano Y, Herranz MA, Kareev IE, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV, Akasaka T, Martin N. J Org Chem. 2009;74:6902–6905. doi: 10.1021/jo9014358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takano Y, Herranz MÁ, Martín N, de Miguel Rojas G, Guldi DM, Kareev IE, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV, Tsuchiya T, Akasaka T. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:5343–5353. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avent AG, Boltalina OV, Goryunkov AV, Darwish AD, Markov VY, Taylor R. Fullerenes Nanotubes Carbon Nanostruct. 2002;10:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shustova NB, Kareev IE, Kuvychko IV, Whitaker JB, Lebedkin SF, Popov AA, Chen YS, Seppelt K, HSS, Boltalina OV. J Fluorine Chem. 2010;131:1198–1212. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuvychko IV, Whitaker JB, Larson BW, Raguindin RS, Suhr KJ, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. J Fluorine Chem. 2011;132:679–685. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuvychko IV, Whitaker JW, Larson BW, Folsom TC, Shustova NB, Avdoshenko SM, Chen Y-S, Wen H, Wang X-B, Dunsch L, Popov AA, Boltalina OV, Strauss SH. Chem Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1039/C2SC01133F. Advance Article. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shustova NB, Kuvychko IV, Peryshkov DV, Whitaker JB, Larson BW, Chen YS, Dunsch L, Seppelt K, Popov AA, HSS, Boltalina OV. Chem Commun. 2010;47:875–877. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03247f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boltalina OV, Lukonin AY, Street JM, Taylor R. Chem Commun. 2000:1601–1602. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuvychko IV, Streletskii AA, Shustova NB, Seppelt K, Drewello T, Popov AA, Strauss SH, Boltalina OV. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6443–6462. doi: 10.1021/ja1005256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorozhkin EI, Goryunkov AA, Ioffe IN, Avdoshenko SM, Markov VY, Tamm NB, Ignat’eva DV, Sidorov LN, Troyanov SI. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:5082–5094. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krusic PJ, Wasserman E, Parkinson BA, Malone B, Holler ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6274–6275. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fagan PJ, Krusic PJ, McEwen CN, Lazar J, Parker DH, Herron N, Wasserman E. Science. 1993;262:404–407. doi: 10.1126/science.262.5132.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borghi R, Lunazzi L, Placucci G, Krusic PJ, Dixon DA, Knight J, LB J Phys Chem. 1994;98:5395–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borghi R, Lunazzi L, Placucci G, Krusic PJ, Dixon DA, Matsuzawa N, Ata M. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7608–7617. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morton JR, Preston KF. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:4993–4997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morton JR, Negri F, Preston KF, Ruel G. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:10114–10117. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida M, Morinaga Y, Iyoda M, Kikuchi K, Ikemoto I, Achiba Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7629–7632. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida M, Morishima A, Morinaga Y, Iyoda M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:9045–9046. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida M, Sultana F, Uchiyama N, Yamada Y, Iyoda M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:735–736. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen W, McCarthy TJ. Macromol. 1999;32:2342–2347. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duan YY, Shi L, Sun LQ, Zhu MS, Han LZ. Int J Thermophys. 2000;21:393–404. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doome RJ, Dermaut S, Fonseca A, Hammida M, Nagy JB. Fuller Nanotub Carbon Nanostruct. 1997;5:1593–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doome R, Fonseca A, Nagy JB. Mol Materials. 2000;13:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dolbier J, WR Chem Rev. 1996;96:1557–1584. doi: 10.1021/cr941142c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cowell AB, Tamborski C. J Fluorine Chem. 1981;17:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawada H, Nakayama M. J Fluorine Chem. 1991;51:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bravo A, Bjørsvik H-R, Fontana F, Liguori L, Mele A, Minisci F. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7128–7136. doi: 10.1021/jo970302s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antonietti F, Gambarotti C, Mele A, Minisci F, Paganelli R, Punta C, Recupero F. Eur J Org Chem. 2005:4434–4440. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Li C, Yue W, Jiang W, Kopecek R, Qu J, Wang Z. Org Lett. 2010;12:2374–2377. doi: 10.1021/ol1007197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Q-L, Huang Y-Z. J Fluorine Chem. 1989;43:385–392. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loy RN, Sandford MS. Org Lett. 2011;13:2548–2551. doi: 10.1021/ol200628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avila DV, Ingold KU, Lusztyk J, Dolbier WR, Pan HQ. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1577–1579. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avila DV, Ingold KU, Lusztyk J, Dolbier WR, Pan HQ, Muir M. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antonietti F, Mele A, Minisci F, Punta C, Recupero F, Fontana F. J Fluorine Chem. 2004;125:205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruoff RS, Tse DS, Malhotra R, Lorents DC. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:3379–3383. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirsch A, Brettreich M. Fullerenes – Chemistry and Reactions. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005. p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chambers RD. Fluorine in Organic Chemistry. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krause N. Modern Organocopper Chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomashenko OA, Grushin VV. Chem Rev. 2011;111:4475–4521. doi: 10.1021/cr1004293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uzkikh IS, Dorozhkin EI, Boltalina OV, Boltalin AI. Dokl Akad Nauk. 2001;379:344–347. [Google Scholar]