Abstract

Uga3p, a member of zinc binuclear cluster transcription factor family, is required for γ-aminobutyric acid-dependent transcription of the UGA genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Members of this family bind to CGG triplets with the spacer region between the triplets being an important specificity determinant. A conserved 19-nucleotide activation element in certain UGA gene promoter regions contains a CCGN4CGG-everted repeat proposed to be the binding site of Uga3p, UASGABA. The function of conserved nucleotides flanking the everted repeat has not been rigorously investigated. The interaction of Uga3p with UASGABA was characterized in terms of binding in vitro and transcriptional activation of lacZ reporter genes in vivo. Electromobility shift assays using mutant UASGABA sequences and heterologously produced full-length Uga3p demonstrated that UASGABA consists of two independent Uga3p binding sites. Simultaneous occupation of both Uga3p binding sites of UASGABA with high affinity is essential for GABA-dependent transcriptional activation in vivo. We present evidence that the two Uga3p molecules bound to UASGABA probably interact with each other and show that Uga3p(1–124), previously used for binding studies, is not functionally equivalent to the full-length protein with respect to binding in vitro. We propose that the Uga3p binding site is an asymmetric site of 5′-SGCGGNWTTT-3′ (S = G or C, W = A, or T and n = no nucleotide or G). However, UASGABA, is a palindrome containing two asymmetric Uga3p binding sites.

Many transcription factors of the binuclear zinc cluster family have been characterized in fungi (1). These proteins possess DNA-binding and dimerization domains at their N termini and activation domains at their C termini. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Uga3p is required for transcriptional activation of the UGA11 (γ-aminobutyrate:2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase) and UGA4 (γ-aminobutyrate-specific permease) genes of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) degradative pathway (2). This DNA-binding protein has a zinc cluster motif in its N terminus and an acidic C terminus similar to activation domains characterized in other zinc cluster proteins (3, 4). UGA4 expression is higher at acidic pH probably regulated by Rim101p (5). A conserved 19-bp GC-rich region, which is essential for GABA-induced transcription and designated, is present in the UGA1 and UGA4 promoters. The GC-rich core of the UGA4 element is a perfect 10-bp palindrome, whereas the corresponding UGA1 region is an imperfect palindrome differing from it by a single nucleotide (4, 6). The deletion of a second UGA4 regulatory sequence, UASGATA, decreases GABA-induced UGA4 expression by 80% (4). High level UASGATA-mediated expression in uga43/dal80 cells is sensitive to nitrogen catabolite repression, because it is abolished when the cells are grown with as the sole nitrogen source (7–10).

The most extensively studied member of the zinc binuclear cluster family, Gal4p, is a transcriptional activator of the galactose pathway (GAL) genes (11, 12). In vitro binding studies using a purified Gal4p truncation (amino acids 1–140) containing the entire DNA binding and dimerization domains demonstrated that the CGG triplets and proper spacing between them are vital for protein binding to DNA (13). The nature of residues between the CGG triplets, however, is not crucial to binding, which generates a “sloppy” binding specificity in vitro. X-ray crystallographic studies of a Gal4p(1–65)·DNA complex revealed that the protein binds to the CGG residues on opposite strands of UASGAL, leaving space in the major groove for an additional protein molecule to bind (14).

Crystal structures of protein-DNA complexes (e.g. Leu3p and Put3p) show that zinc binuclear cluster proteins bind CGG repeats, most of them being thought to bind as homodimers with each monomer recognizing a CGG triplet (15). The GC-rich core region of zinc cluster binding sites has been classified as palindromes, direct repeats, or everted repeats (16). An exception is the hexose transporter protein transcriptional re-pressor Rgt1p in S. cerevisiae, which binds non-cooperatively as a monomer to an asymmetric site (17). The consensus for UASGAL binding Gal4p is CGG-N11-CCG (11), whereas Put3p binds to a pair of CGG motifs separated by 10 bp (15). Ppr1p (an activator of pyrimidine pathway genes), Hap1p (an activator of the genes for cellular respiration), and Pdr3p (an activator of multidrug resistance genes) bind to CGG elements separated by 6 bp. The difference in these binding sites is that the Ppr1p binding site is a palindrome (18) and Hap1p binds to direct repeats (19), whereas Pdr3p binds to everted repeats (15). All three proteins bind as homodimers with spacing between the CGG triplets being vital for recognition and binding. The A and T sequences immediately flanking the UASGAL GC-rich consensus sequence do not influence binding specificity (20). Leu3p, an activator of the leucine synthesis pathway, and Uga3p both recognize an everted CCG-N4-CGG sequence with the spacer sequence reported to specify recognition by Leu3p or Uga3p (21).

More than 1,200 regions in the S. cerevisiae genome contain the CCG-N4-CGG motif (Saccharomyces genome data base), which makes the physiological relevance of potential protein binding to these sites an interesting question. In this paper, we demonstrate that in addition to the CCG-N4-CGG motif, the nucleotides flanking this everted repeat are also essential for high affinity Uga3p binding and activation of transcription. We propose that UASGABA is a palindrome consisting of two independent Uga3p binding sites, each with the sequence 5′-SGCGGNWTTT-3′(S = G or C, W = A or T, and n = no nucleotide or G). Simultaneous occupation of both sites is essential for GABA-dependent transcriptional activation in vivo, and it is likely that the two Uga3p molecules bound to UASGABA interact with each other. Uga3p(1–124), previously used for binding studies, is not functionally equivalent to the full-length protein with respect to binding in vitro. This raises the possibility that the binding specificity determined with truncations of other members of the zinc binuclear cluster family may need to be reevaluated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Plasmids

Uga3p Expression Vector

Vector pT7-7 (pT7) (22) was digested with BstB1, treated with Klenow fragment to create blunt ends, and religated to yield pT7-7a from which the BstBI site had been removed. A double-stranded oligonucleotide with NdeI and BamHI extensions encoding a 9-amino acid influenza hemagglutinin protein (HA) epitope tag and the first 14 amino acids of Uga3p was generated by annealing oligonucleotides RD55A 5′-TATGTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTA-CGCTATGAATT ATGGCGTGGAGAAGCTGAATTGAAATATTCGAA-GCAG-3′ and RD55B 5′-GTACCTGC TTCGAATATTTCAATTTCAGC-TTCTCCACGCCATAATTCATAGCGTAGTCGGGACGTCGTATGGTACA-3′. This fragment was inserted into pT7-7a vector to create pRD106. The remainder of Uga3p was inserted into pRD106 by subcloning the 1,820-bp BstBI and HindIII fragment from the 2,068-bp HindIII fragment containing the UGA3 gene from S. cerevisiae strain S288c (23). This created the expression vector pRD107 in which the full-length UGA3p coding sequence is fused in frame to the HA tag. The His6-tagged Uga3p construct was generated by inserting an oligonucleotide encoding a methionine followed by six histidine residues immediately upstream of the codon for the N-terminal methionine of an untagged Uga3p expression construct made using the expression vector pRD107.

Reporter Gene Constructs

Oligonucleotides corresponding to wild type and mutant UASGABA alleles (Table I) were purified by thin layer chromatography, annealed, and cloned into the SalI and EagI sites of the CYC1 promoter region of ARS CEN URA3 lacZ expression vector, pHP41 (24). The reporter constructs were named as the pUGA series (i.e. reporter clone with UAS70 was named pUGA70). All selected constructs were verified by sequencing.

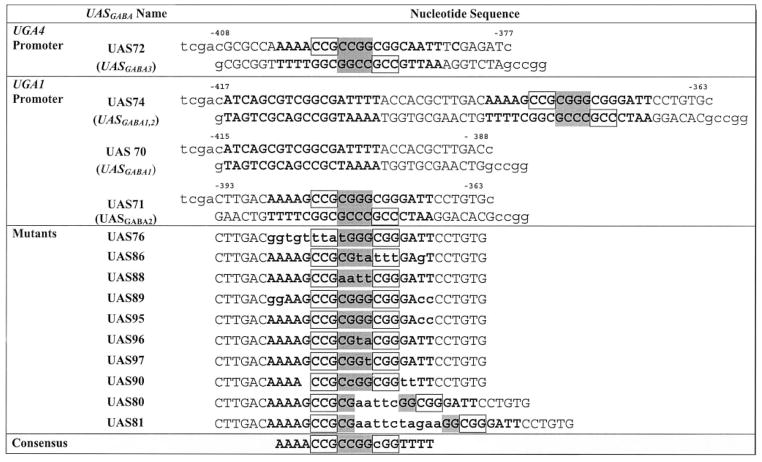

Table I. Oligonucleotides used during this study.

Bold lettering denotes the UASGABA sequence with mutated nucleotides indicated in lower case. The everted CGG repeats are boxed, whereas shaded nucleotides represent the spacer region.

|

Expression of Plasmids and Cell-free Protein Extraction

Plasmids carrying expression constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3), and cell-free protein extraction was carried out as described by Dorrington and Cooper (25).

Electromobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)

EMSAs were performed as described by Cunningham et al. (6) using cell-free extracts (~2.5–5 μg of protein/reaction) from the expression of pRD106 (HA tag) and pRD107 (Uga3p). Oligonucleotide probes (Table I), labeled by filling in their 5′ extensions with [α-32P]dCTP, and Klenow fragment were purified on a 5% polyacrylamide gel.

Growth of Yeast Cells and β-Galactosidase Assays

S. cerevisiae TCY1 (matα, ura3, lys2) (6) was transformed with the lacZ reporter constructs or negative control pHP41. Colonies were patched on the fourth day on selective medium (YNB (Difco) − uracil + lysine). On day 6, the patches were inoculated into medium containing 0.17% YNB (without amino acids or ammonium sulfate, pH 5.5), 2% glucose as the carbon source, proline (0.1%), or proline (0.1%) + GABA (0.1%) as the sole nitrogen sources. The medium was supplemented with histidine (20 μg/ml), arginine (20 μg/ml), and lysine (40 μg/ml) to cover auxotrophic requirements (26). β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described by Kovari et al. (27). The results are represented as percentile values of the Miller units obtained from the mean of three or four experiments, each performed in triplicate with the variation between experiments of <25%. Percentile values were calculated relative to the β-galactosidase activity of S. cerevisiae cells containing pUGA71.

RESULTS

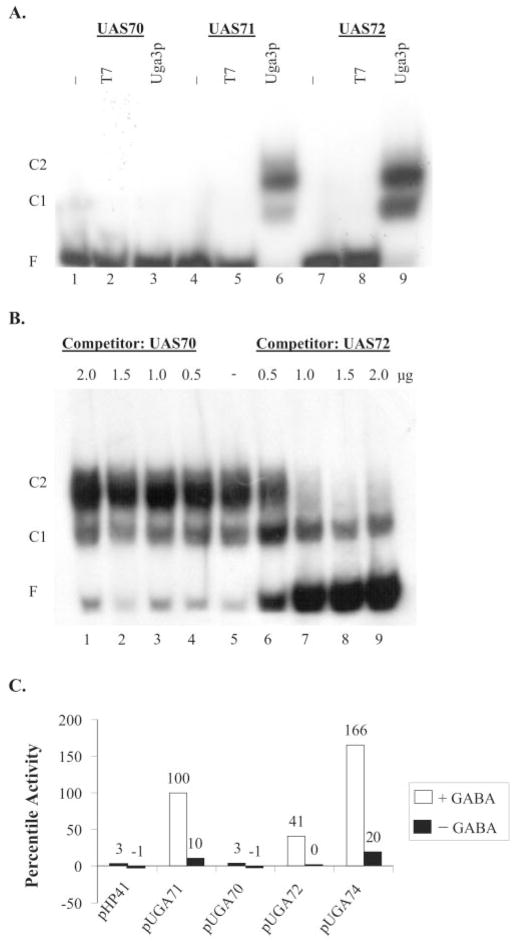

Uga3p Binding to Wild Type UGA1 and UGA4 UASGABA Elements

The two UASGABA elements upstream of UGA1(UASGABA1 and UASGABA2, respectively) and one element upstream of UGA4 (UASGABA3) (Table I) were used in initial binding studies to identify the sequence with highest affinity for Uga3p. The nucleotide sequences selected for each element excluded any potential UASNTR (GATA) elements. Two distinct complexes (C2 and C1 in Fig. 1A, lanes 6 and 9) appeared with wild type UAS71 and UAS72. However, Uga3p was unable to bind to UAS70 (Fig. 1A, lane 3). In contrast to UAS72, UAS70 was unable to compete with UAS71 for Uga3p binding even at high concentrations (Fig. 1B). In vivo GABA-dependent reporter gene expression supported by the three UASGABA elements corresponded to the in vitro binding results. pUGA70 supported little or no detectable β-galactosidase production, whereas pUAS72 supported about half as much activity as pUAS71 (Fig. 1C). The wild type UGA1 promoter fragment in pUGA74 containing both UAS70 and UAS71 (Table I) supported significantly higher expression than pUGA71. This finding suggests that UAS70, although unable to activate transcription on its own, can contribute to overall transcription in combination with UAS71 (Fig. 1C). Because UAS71 gave the highest in vivo activity, it was used for further binding studies.

Fig. 1. In vitro binding of Uga3p and in vivo GABA-dependent activity of wild type UASGABA elements.

A, EMSA of probes UAS70, UAS71, and UAS72 with E. coli extracts containing overexpressed Uga3p. −, labeled probe alone; T7, probe + HA tag (pRD106 extract); Uga3p, probe + HA-Uga3p (pRD107 extract). C1 and C2 denote higher and lower mobility complexes, respectively, and F indicates free unbound probe. B, EMSA analysis of competition of labeled probe UAS71 with UAS70 and UAS72 for binding to Uga3p. The concentration of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotide (in microgram per 20-μl reaction volume) is indicated above each lane. C, UAS-mediated β-galactosidase activities shown as LacZ percentile activity of pHP41 (no insert), pUGA70, pUGA71, pUGA72, and pUGA74 with reporter gene expression supported by UAS71 in pUGA71 set at 100%. Unshaded and shaded areas denote GABA-dependent and GABA-independent values, respectively.

Uga3p Binds to One or the Other Site within UASGABA

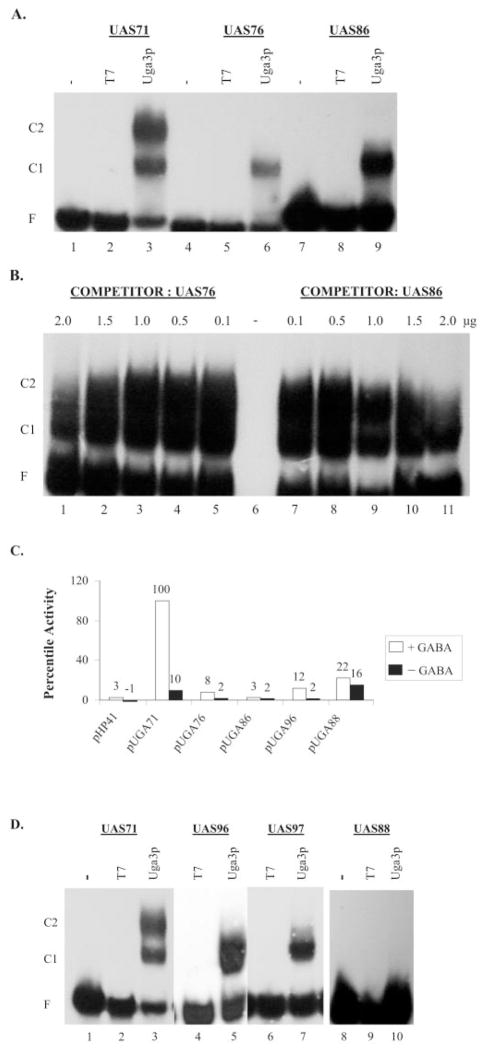

The presence of two different mobility complexes (Fig. 1A, C2 and C1) suggested that (i) two Uga3p molecules bind to UAS71 in vitro and (ii) UASGABA consists of two Uga3p binding sites. To investigate this possibility, the left and right halves of UAS71 were mutated (Table I, UAS86 and UAS76, respectively) and assayed for their ability to bind Uga3p. In both cases, only the higher mobility shift complex, C1 (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 6 and 9 with lane 3) occurred, suggesting the occupancy of only one site within UASGABA. By this reasoning, the lower mobility shift complex C2 probably represents the occupancy of both sites. These results also show that Uga3p is able to bind independently to each half of UASGABA. UAS76 and UAS86 are equally weak competitors of UAS71 for Uga3p binding (Fig. 2B), indicating that sequence differences between the two sites did not detectably influence the affinity of Uga3p binding. Neither UAS76 nor UAS86 is able to mediate significant reporter gene expression in vivo (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. In vitro Uga3p binding and in vivo GABA-dependent activity of UASGABA2 half-sites.

A, EMSA of probes UAS71, UAS76 (left half-mutated), and UAS86 (right half-mutated) with E. coli extracts containing overexpressed Uga3p. −, labeled probe; T7, probe + HA tag (pRD106 extract); and Uga3p, probe + HA-Uga3p (pRD107extract). B, competition of probe UAS71 with unlabeled half-site mutant oligonucleotides UAS76 and UAS86 for binding to Uga3p. C, UAS-mediated β-galactosidase activities indicated as LacZ percentile activity of pHP41 (no insert), pUGA71, pUGA76, pUGA86, pUGA96, and pUGA88, with β-galactosidase activity supported by UAS71 in pUGA71 set at 100%. Open and black bars denote GABA-dependent and GABA-independent activities, respectively. D, EMSA of probes UAS71, UAS96, and UAS97 (left half-spacer mutated) and UAS88 (left and right half-spacer mutated) with E. coli extracts containing overexpressed Uga3p. −, labeled probe; T7, probe + HA tag (pRD106 extract); and Uga3p, probe + HA-Uga3p (pRD107 extract). Other designations are as indicated in Fig. 1.

Role of the Spacer Region in UASGABA

Previously, Noël and Turcotte (21) showed that a four-nucleotide spacer sequence (CGGG) between the everted CCG repeats is required for a truncated His6-tagged Uga3p(1–124) to recognize UASGABA (Table II, data in Ref. 21 summarized in section C). We tested three mutant UAS71 sequences, UAS88, UAS96, and UAS97, with substitutions in either the whole spacer sequence or the right half, respectively (Table I) for their ability to bind the full-length Uga3p and mediate transcription. No shifts were present when UAS88 was used as a probe (Fig. 2D, lane 10), confirming that mutation of the whole spacer abolishes Uga3p binding. Only the higher mobility complex C1 appeared in binding assays of Uga3p with UAS96 and UAS97, indicating the occupation of the left binding site (Fig. 2D, lanes 5 and 7). The loss of the lower mobility shift complex C2 with UAS97 showed that the 3′-G in the right half of the spacer was essential for Uga3p binding to this half of UASGABA. Compared with UAS71, there was an 8-fold drop in UAS96-mediated reporter gene activity in vivo. The low level of reporter gene expression in cells transformed with pUGA88 was GABA-independent, suggesting that factors other than Uga3p were functioning here in vivo (Fig. 2C).

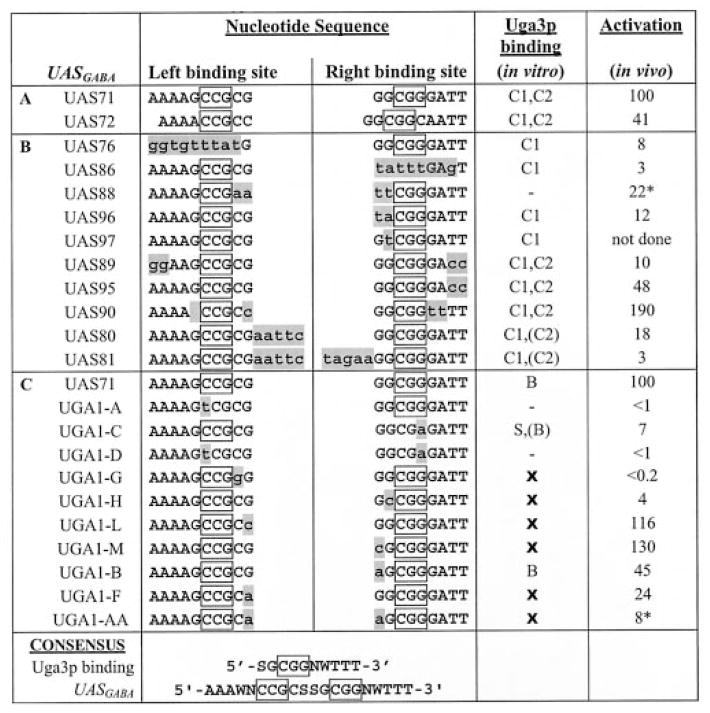

Table II. Uga3p binding activity in vitro and transcriptional activation in vivo: Summary of wild type and mutant UASGABA sequences.

The top strand of wild type and mutant UASGABA sequences is shown with introduced mutations represented in shaded lowercase and boxed sequences, indicating the designated everted CGG repeat sequences. S = G or C, W = A, or T and N = no nucleotide or G. C1 and C2 represent the higher and lower mobility complex observed in EMSA with HA-Uga3p, whereas S and B denote the higher and lower mobility shifts observed by Noël and Turcotte (21) in EMSAs using His6-Uga3p(1–124) and (−) indicates no complexes observed. In vivo GABA-dependent activation is expressed as percentage of lacZ reporter gene activity of the wild type UAS71. Asterisks indicate GABA-independent lacZ reporter gene activity. A, wild type UASGABA sequences. EMSAs were performed with full-length Uga3p overexpressed in E. coli. B, mutant UAS71 sequences used in this study. EMSAs were performed with full-length Uga3p overexpressed in E. coli. C, mutant UASGABA2 (UAS71) sequences used in the study by Noël and Turcotte (Fig. 1) (21). EMSAs were performed with the truncated His6-Uga3p(1–124). In vivo studies were performed in S. cerevisiae strain YPH499, and GABA-dependent activation activity is expressed here as a percentage of lacZ reporter gene activity of the wild type UASGABA2, UAS71. X represents EMSAs not done.

|

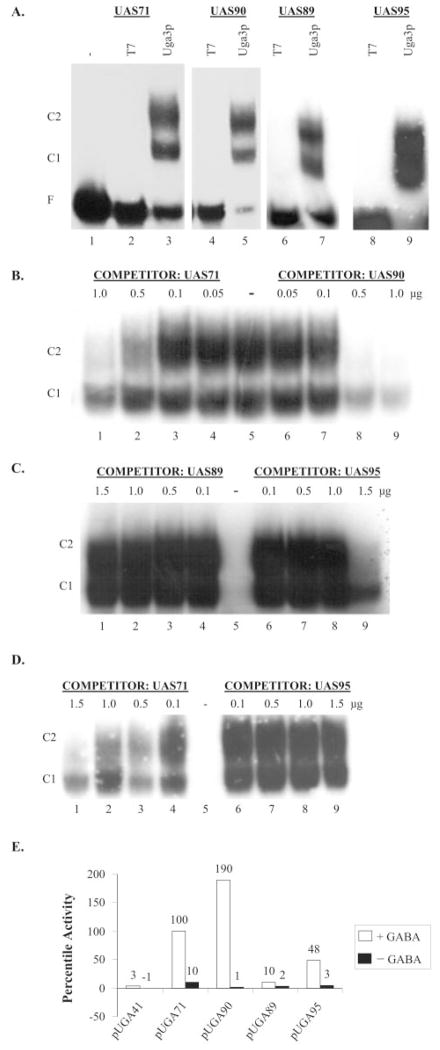

Sequences Flanking the Everted CGG Repeats Are Required for Strong Uga3p Binding

A comparison of the UASGABA elements in the promoter regions of UGA1 and UGA4 suggested that the consensus sequence of UASGABA might be an 18-nucleotide palindrome, AAAACCGCCGGCGGTTTT (UAS90). Both the C1 and C2 complexes occurred in EMSA analysis of Uga3p binding to UAS90 (Fig. 3A, lane 5). However, Uga3p binding affinity for UAS90 was higher than that for UAS71 (Fig. 3B) as was GABA-dependent LacZ expression (Fig. 3E), showing that a perfect palindrome mediated 2-fold more GABA-dependent transcription than the wild type UAS71 sequence (Fig. 3E). The everted CGG repeats and spacer sequences of UAS72 and UAS90 are identical, but UAS72 mediated 5-fold less GABA-dependent expression in vivo than UAS90 (Fig. 1C versus Fig. 3E). Because UAS72 differs from UAS90 only in the sequence 3′ of the everted repeat, these data suggest that this region plays a role in Uga3p binding and transcriptional activation. We tested this finding using mutant UAS71 sequences UAS95 and UAS89 in which the TT nucleotides flanking 3′-everted repeat or both the AA and TT nucleotides 5′ and 3′ of the everted repeats, respectively, were mutated (Table I). Both the C1 and C2 complexes occurred in the binding assays of UAS89 and UAS95 (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 and 9). However, competition assays with UASGABA2 showed that Uga3p binding to UAS95 and UAS89 was weaker than Uga3p binding to UAS71 with UAS89 being the weaker competitor relative to UAS95 (Fig. 3, C and D). pUGA89 and pUGA95 supported 10- and 2-fold less reporter gene expression than the wild type UAS71 with the expression supported by pUGA95 and pUGA72 being similar (Fig. 3C). Together, these data indicate that although the A/T nucleotides 5′ and 3′ to the everted CCG repeats are not detectably required for the recognition of UASGABA2, they influence Uga3p binding affinity and are essential for transcription in vivo.

Fig. 3. In vitro Uga3p binding and in vivo assays of UASGABA elements with mutations in the regions flanking the everted CCG repeats.

A, EMSA of probes UAS71, UAS90 (perfect palindrome), UAS89 (5′-AA and 3′-TT sequences mutated), and UAS95 (3′-TT mutated) with E. coli extracts containing overexpressed Uga3p. −, labeled probe only; T7, probe + HA tag (pRD106 extract); and Uga3p, probe + HA-Uga3p (pRD107extract). Designations are indicated in Fig. 1. B–D, competition of UAS71 with UAS90, UAS89, and UAS95, respectively, for binding to Uga3p. The concentrations of competitors are indicated above each lane in microgram per 20-μl reaction volume. −, no competitor. E, UAS-mediated β-galactosidase activities indicated as LacZ percentile activity of pHP41 (no insert), pUGA71, pUGA90, pUGA89, and pUGA95 with β-galactosidase activity supported by UAS71 in pUGA71 set at 100%. Open and black bars denote GABA-dependent and GABA-independent activities, respectively.

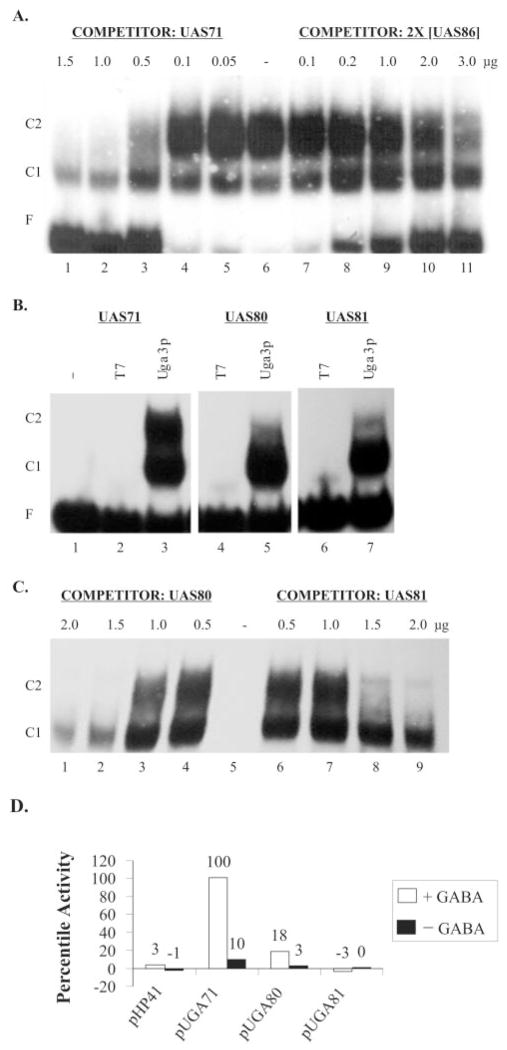

Interaction between Uga3p Molecules at UASGABA

Several members of the zinc cluster family dimerize (14, 28–30). The presence of two different mobility shift complexes in Uga3p binding studies with UAS71 led to the question of whether simultaneous occupation of both Uga3p binding sites in UASGABA involved the interaction between the Uga3p molecules. We investigated whether Uga3p binding affinity to the full UASGABA (represented by UAS71) was greater than Uga3p binding affinity to a single site (represented by UAS86). UAS71 competed ~6-fold better for Uga3p binding than did twice as much UAS86 (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 11), suggesting that complex C2 with both binding sites occupied had a higher affinity for Uga3p than complex C1 in which Uga3p binds to a single site. One way of explaining this result is to suggest that two Uga3p molecules occupying UASGABA might interact with each other. To test this finding, 5 (UAS80) and 10 (UAS81) nucleotides were introduced into the spacer region of UASGABA2 (Table I). UAS80 and UAS81 bind Uga3p dramatically less well than wild type (UAS71) as seen by the reduced amount of complex C2 (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 7), suggesting that Uga3p binds to one or the other site despite the relative distances between repeats but not to both binding sites simultaneously. Competition of UAS80 and UAS81 with the wild type UAS71 yielded similar results, although UGA80 appears to be a slightly better competitor than UAS81 (Fig. 4C). These observations correlated with in vivo reporter gene expression, which was 5-fold lower with pUGA80 compared with pUGA1. No β-galactosidase activity was detected in cells transformed with pUGA81 (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. Interaction between Uga3p molecules binding to UASGABA.

A, competition of UAS71 with equimolar concentrations of UAS86 for binding to Uga3p. The concentrations of competitors are indicated above each lane in microgram per 20-μl reaction volume. −, no competitor. B, EMSA of UAS71, UAS80 (5-nucleotide insertion in spacer), and UAS81 (10-nucleotide insertion in spacer) with E. coli extracts containing overexpressed Uga3p.−, labeled probe only; T7, probe + HA tag (pRD106 extract); and Uga3p, probe + HA-Uga3p (pRD107 extract). C, competition of probe UAS71 with unlabeled UAS80 and UAS81 for binding to Uga3p. The concentrations of competitors are indicated above each lane in microgram per 20-μl reaction volume. −, no competitor. D, UAS-mediated β-galactosidase activities indicated as LacZ percentile activity of pHP41 (no insert), pUGA71, pUGA80, and pUGA81 with β-galactosidase activity supported by UAS71 in pUGA71 set at 100%. Open and black bars denote GABA-dependent and GABA-independent activities, respectively.

Truncated Uga3p(1–124) Is Not Functionally Equivalent to the Full-length Protein

A comparison of our results (Table II, sections A and B) with those of Noël and Turcotte (21) summarized in Table II, section C, showed three discrepancies between the ability of HA-Uga3p (HA-tagged full-length protein) and a His6-Uga3p(1–124) truncation to bind to mutant UASGABA sequences in vitro. (i) Noël and Turcotte (21) observed only a single complex in binding studies of UAS71 with His6-Uga3p(1–124) in contrast to our results with HA-Uga3p. (ii) No DNA-protein complex was found when His6-Uga3p(1–124) was used to bind UGA1-A (Table II, section C) in which a T substitutes for the first C of the left binding site, and we observed the presence of higher mobility complex C1 with the right half of UASGABA mutated (UAS76) with HA-Uga3p as the source of protein (Fig. 2A, lane 6). (iii) Two complexes were produced in EMSA analysis of UGA1-C with His6-Uga3p(1–124), although our equivalent UAS86 showed only a single shift with full-length Uga3p (Fig. 2A, lane 9). Reporter gene expression supported by the UASGABA mutants in S. cerevisiae cells expressing full-length Uga3p was the same in both studies.

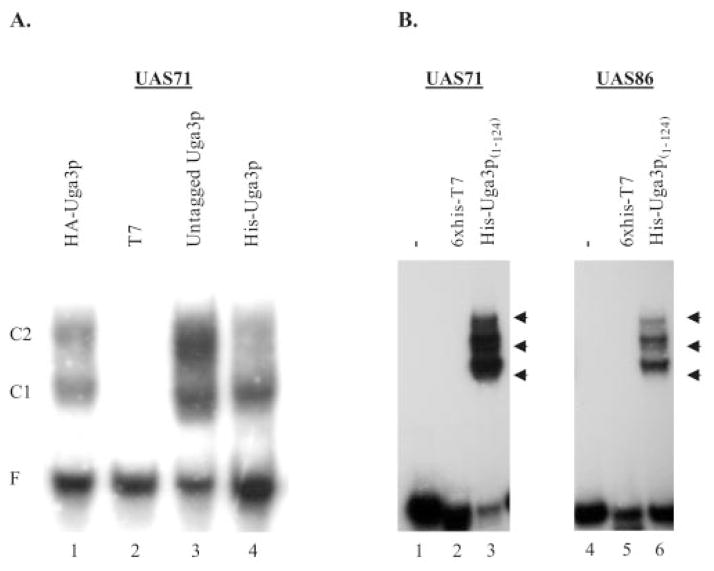

To eliminate possible interactions because of the HA epitope tag, pRD107 was engineered to either remove the HA-coding sequence (untagged Uga3p) or replace it with a His6 tag (His-Uga3p). EMSA of both untagged and His-tagged Uga3p with UAS71 showed the same shift patterns as observed with HA-Uga3p (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4 versus lane1). The shift with untagged Uga3p confirmed that the presence of the HA tag was not responsible for the two shifts observed in binding studies. A reduction in the lower mobility shift complex C2 was consistently observed with His6-Uga3p.

Fig. 5. In vitro binding of full-length versus truncated Uga3p to UASGABA.

A, EMSA analysis of UAS71 with E. coli extracts containing either overexpressed full-length Uga3p (Untagged Uga3p) or Uga3p tagged with the HA epitope (HA-Uga3p), six His residues immediately following the N-terminal methionine (His-Uga3p), and vector only (T7). B, EMSA analysis of UAS71 and UAS86 with a His6-tagged Uga3p(1–124) truncation of His-Uga3p. EMSAs with Uga3p(1–124) were analyzed using 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels as opposed to 4% for EMSA with the full-length Uga3p. His6-T7 denotes E. coli cell-free extracts containing a derivative pT7-7 expressing just a me-thionine plus six histidine residues inserted upstream of the NdeI site.

Therefore, we tested the possibility that full-length Uga3p might not be functionally equivalent to the Uga3p(1–124) truncation. The binding studies of E. coli extracts containing Uga3p(1–124) with UAS71 revealed three shift complexes (Fig. 5B, lane 3) as opposed to the two shifts obtained with the full-length Uga3p (Fig. 5A, lanes 1, 3, and 4). Interestingly, all three shift complexes were still present in EMSA of Uga3p(1–124) with UAS86 (Fig. 5B, lane 6), which produces only one shift with the full-length Uga3p (Fig. 2, lane 9). Based on these data, we conclude that full-length and truncated Uga3p are not functionally equivalent with respect to UASGABA recognition and binding affinity.

DISCUSSION

Consensus based upon conservation of the UASGABA sequences of UGA1 and UGA4 together with binding studies in this study lead us to propose that UASGABA consists of two palindromic Uga3p binding sites with the asymmetric consensus 5′-SGCGGNWTTT-3′(S = G or C, W = A or T, and n = no nucleotide or G). The two nucleotides 5′ to the CGG motif (SG) are essential for binding specificity. Evidence supporting this was provided by binding data with UAS97 (Table II, section B) where the G nucleotide was mutated and previous studies using UGA1-L, UGA1-F, and UGA1-AA (Table II, section C). The 3′-A/T sequences influence Uga3p binding affinity, which is essential for mediating transcriptional activation in vivo. The latter finding is consistent with the conservation of these A/T sequences in wild type UASGABA sequences situated upstream of UGA1 and UGA4 (Table I) and with data generated with UAS72, UAS90, UAS95, and UAS89 (Table II, section B).

Although Uga3p appears to bind independently to each binding site, there is evidence of interaction between the Uga3p molecules occupying the two binding sites of UASGABA. This interaction increases the affinity between DNA and Uga3p and is essential for Uga3p to mediate GABA-dependent transcriptional activation in vivo. In addition to determining binding specificity, the two nucleotides 5′ of the CGG motif appear to be responsible for the two Uga3p molecules occupying UASGABA in an orientation that permits them to interact with one another. The competition data of two cis-Uga3p binding sites (UAS71) versus a single binding site (2′ UAS86) strongly supports cooperative binding by Uga3p at UASGABA.

Whether or not Uga3p binds to UASGABA as a monomer or dimer remains to be elucidated. Because Uga3p molecules were produced in E. coli grown in the absence of GABA bind to UASGABA, binding appears to be independent of GABA. GABA may function at the level of transcriptional activation rather than DNA binding as it occurs with Dal82p (25) and Put3p (33).

This study presents evidence that additional residues C-terminal of Uga3p amino acids 1–124 (encoding the zinc cluster domain, a linker region, and putative coiled coil domain) are involved in UASGABA recognition and binding. This derives from the finding that binding data with full-length Uga3p presented here did not correlate with results using truncated Uga3p(1–124), leading us to conclude that the truncated protein is not functionally equivalent to the full-length Uga3p with respect to DNA binding. This is pertinent because the binding of zinc cluster proteins to their target UAS sequences has been extensively studied, primarily using truncated proteins containing zinc cluster and putative coiled-coil domains separated by short linker residues (31). Crystallographic data indicate that GAL4p(1– 65) forms a relatively open complex with UASGAL, which probably allows additional residues to participate in determining binding specificity (14, 32). These residues have been proposed to reside in a conserved middle homology region found in almost all of the zinc cluster proteins. The middle homology region has been suggested to function in reducing the ability of the zinc cluster domain to bind to “wrong” UAS sequences (31). Although computer analysis has not identified a middle homology region in Uga3p (31), it is probable that residues functioning as a middle homology region are situated C-terminal of amino acid residues 1–124. We have identified a putative WD-40-like motif (34) in this region that might be involved in determining DNA binding specificity of Uga3p (35). Differences in binding characteristics between Uga3p and Uga3p(1–124) raise the possibility that other zinc cluster binding studies using truncated proteins may have yielded incomplete characterizations.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the Rhodes University Joint Research Council.

The abbreviations used are: UGA1, γ-aminobutyrate:2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase; UGA4, γ-aminobutyrate-specific permease; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; UAS, upstream activation sequence; HA, hemagglutinin; EMSA, electromobility shift assay; YNB, yeast nitrogen base; NTR, nitrogen-regulated.

References

- 1.Dhawale SS, Lane AC. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5537–5546. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vissers S, André B, Muyldermans F, Grenson M. Eur J Biochem. 1989;181:357–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.André B. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;220:269–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00260493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talibi D, Grenson M, André B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:550–557. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moretti MB, Batlle A, García SC. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham TS, Dorrington RA, Cooper TG. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4718–4725. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4718-4725.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daugherty JR, Rai R, Elberry HM, Cooper TG. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:64–73. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.64-73.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffman JA, Elberry HA, Cooper TG. J Bacteriol. 1997;176:7476–7483. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7476-7483.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffman JA, Cooper TG. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5609–5613. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5609-5613.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soussi-Boudekou S, Vissers S, Urrestarazu A, Jauniaux JC, André B. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1157–1168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3021665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giniger E, Varnum SM, Ptashne M. Cell. 1985;40:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan T, Coleman JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3145–3149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vashee S, Xu H, Johnston SA, Kodadek T. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24699–24706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmorstein R, Carey M, Ptashne M, Harrison SC. Nature. 1992;356:408–414. doi: 10.1038/356408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellauer K, Rochon M, Turcotte B. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6096–6102. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamane Y, Hellauer K, Rochon MH, Turcotte B. J Biol Chem. 1998;17:18556–18561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenouvel F, Nikolev I, Felenbok B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15521–15526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy A, Exinger F, Losson R. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5257–5270. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Guarente L. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2110–2119. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.17.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bram RJ, Kornberg RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:43–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noël J, Turcotte B. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17463–17468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabor S. In: Current Protocol in Molecular Biology. Ausubel FA, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Greene Publishing and Wiley Inter-science; New York: 1990. pp. 16.2.1–16.2.11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose MD, Novick P, Thomas JH, Botstein D, Fink GR. Gene (Amst) 1987;60:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park HD, Luche RM, Cooper TG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1909–1915. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.8.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorrington RA, Cooper TG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3777–3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKelvey J, Rai R, Cooper TG. Yeast. 1990;6:263–270. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovari L, Sumrada R, Kovari I, Cooper TG. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5087–5097. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szi JY, Kohlhaw GB. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2505–2512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carey M, Hakidani H, Leatherwood J, Mostashari F, Ptashne M. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:423–432. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King DA, Zhang L, Guarente L, Marmorstein R. Eur J Morphol. 1999;36:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schjerling P, Holmberg S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4599–4607. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmorstein R, Harrison SC. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2504–2512. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axelrod JD, Majors J, Brandriss MC. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:564–567. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L, Gaitataze C, Neer EJ, Smith TF. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2470–2476. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Idicula AM. PhD thesis. Rhodes University; Grahamstown, South Africa: 2002. Binding and Transcriptional Activation by Uga3p, a Zinc Binuclear Cluster Protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Redefining the UAS-GABA and the Uga3p Binding Site. [Google Scholar]