Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disorder in the United States [1]. Symptomatic disease in the knee and hip occurs in approximately 6% and 3%, respectively, of adults 30 years of age or older [2]. From 1995 to 2005, the number people affected with symptomatic OA has grown from 21 million to nearly 27 million in the United States, probably reflecting the aging of the population and the obesity epidemic [3].

Pain from OA is a key symptom in the decision to seek medical care and is an important antecedent to disability [4]. Because of its high prevalence and the frequent disability that accompanies disease in major joints such as the knee and hip, OA accounts for more trouble with climbing stairs and walking than any other disease [5] and is the most common reason for total hip and total knee replacement [6]. The rapid increase in the prevalence of this already common disease suggests that OA will have a growing impact on health care and public health systems in the future [3].

Defining osteoarthritis

Epidemiologic principles can be used to describe the distribution of disease in the population and to examine risk factors for its occurrence, its development, or its progression. For the purpose of epidemiologic investigation, OA can be defined pathologically, radiographically, or clinically. Radiographic OA has long been considered the reference standard, and multiple ways to define radiographic disease have been devised. The Kellgren-Lawrence radiographic grading scheme and atlas have been in rheumatic.theclinics.com use for more than 4 decades. This overall joint scoring system grades five levels of OA, from 0 to 4, defining OA by the presence of a definite osteophyte, and more severe grades by the presumed successive appearance of joint-space narrowing, sclerosis, cysts, and deformity [7]. Other radiographic metrics have included semiquantitative examination of individual radiographic features, such as osteophytes and joint-space narrowing, or direct measurement of the inter-bone distance as an indicator of the joint-space width in the knees and hips as a potentially more powerful tool to define OA and to investigate progression in epidemiologic studies and clinical trials of disease-modifying therapies [8,9]. More sensitive imaging methods using MRI can visualize multiple structures in a joint and are undergoing evaluation for their role in defining OA and for their usefulness in detecting the effects of potential disease-modifying interventions more quickly than possible with conventional radiographs [10,11]. Similarly, measures of systemic or local biomarkers of joint metabolism thought to be important in the OA process are undergoing evaluation to help sharpen OA definitions for epidemiologic studies, to select appropriate participants for clinical trials, and to follow response to therapy.

Studies of OA in persons who have joint symptoms may be more clinically relevant, because not all persons who have radiographic OA have clinical disease, and not all persons who have joint pain demonstrate radiographic OA [12]. Each set of clinical and radiographic criteria may yield slightly different groups of subjects defined as having OA [12].

Prevalence and incidence of osteoarthritis

The prevalence of OA (ie, the frequency of the disease in the population at a given time) varies according to the definition of OA, the specific joint(s) under study, and the characteristics of the study population. Recently, Lawrence and colleagues [3] summarized findings from several population-based studies and estimated the prevalence of radiographic and symptomatic knee, hand, and hip OA. The age-standardized prevalence of radiographic knee OA in adults over the age of 45 years was 19.2% among the participants in the Framingham Study and 27.8% in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), approximately 37% of participants more than 60 years of age had radiographic knee OA.

The age-standardized prevalence of radiographic hand OA was 27.2% among the Framingham participants. In general, radiographic hip OA was less common than hand or knee OA. In the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, about 7% of women more than 65 years of age had radiographic hip OA. The prevalence of hip OA was much higher in Johnston County, with 27% of subjects at least 45 years old demonstrating radiographic evidence of Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2 OA or higher. Potential explanations for the differences between these studies relate to differences in study populations, definitions of OA, distribution of risk factors for disease, and radiographic readers.

Symptomatic OA generally is defined by the presence of symptoms of pain, aching, or stiffness in a joint with radiographic OA. The age-standardized prevalence of symptomatic hand and knee OA is lower than that of radiographic OA, at 6.8% and 4.9% in Framingham subjects older than 26 years of age. The prevalence of symptomatic knee OA was 16.7% among subjects age 45 years and older in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, much higher than reported in the Framingham Study. About 9% of subjects in the Johnston County study had symptomatic hip OA [3].

There is a paucity of meaningful data on the cumulative incidence or risk of developing OA. Here, the length of time over which the risk of OA is calculated is critical but is not always clearly specified or known. Further, because OA is a chronic disease occurring mostly among the elderly, competing risks or death from other diseases makes direct estimation of the risk of OA difficult.

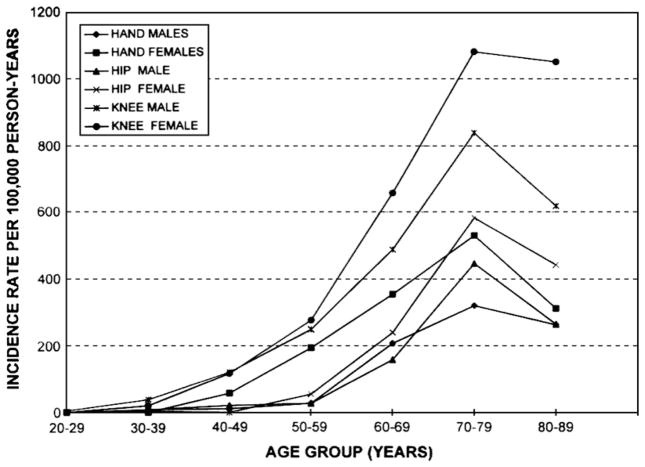

Oliveria and colleagues [13] reported the age- and sex-standardized incidence rates of symptomatic hip, knee, and hand OA to be 88, 240, and 100/100,000 person-years, respectively, in participants in a Massachusetts health maintenance organization (Fig. 1). Recently, Murphy and others [14] estimated the lifetime risk of developing symptomatic knee OA to be about 45%, rising to 66% in obese persons.

Fig. 1.

Incidence of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee in members of the Fallon Community Health Plan, 1991–1992, by age and sex.

(From Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Reed JI, et al. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1139; with permission.)

Risk factors for osteoarthritis

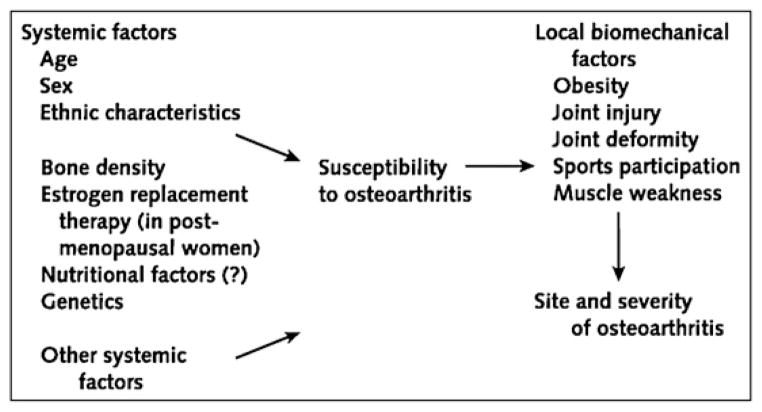

OA has a multifactorial etiology and can be considered the product of an interplay between systemic and local factors, as shown in Fig. 2 [1]. For example, a person may have an inherited predisposition to develop OA but may develop it only if an insult to the joint has occurred. The relative importance of risk factors may vary for different joints, for different stages of the disease, for the development as opposed to the progression of disease, and for radiographic versus symptomatic disease. There even is some evidence suggesting that risk factors may act differently according to individual radiographic features, such as osteophytes and joint-space narrowing [1]. Whether some of these differences are genuine or are spurious results of differences in study populations, definitions of risk factors and OA, or statistical power or analytic methods is open to debate.

Fig. 2.

Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis with putative risk factors.

(From Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:637; with permission.)

Systemic risk factors for osteoarthritis

Age

Age is a one of the strongest risk factors for OA of all joints [1–3]. The increase in the incidence and prevalence of OA with age probably is a consequence of cumulative exposure to various risk factors and biologic changes that occur with aging.

Gender and hormones

Women are more likely to have OA than men, and they may have more severe OA, as well [15]. The definite increase in OA in women around the time of menopause has led to numerous investigations into the relationship between hormonal factors and OA; results have been conflicting [16]. Several studies have shown hormone replacement therapy to be associated with a lower prevalence of radiographic OA in the knee and hip [17,18], but protective effects on joint symptoms have not been shown [19]. Hannan and colleagues [17] reported that long-term estrogen use was moderately but not significantly protective for knee OA and severe knee OA. Nevitt and colleagues [17] found that current estrogen use was associated with a 30% lower risk of radiographic hip OA and a 50% lower risk of severe hip OA, after adjustment for multiple factors. In a randomized clinical trial (the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study) in a group of older postmenopausal women who had heart disease, however, no significant difference was found in the prevalence of knee pain or its associated disability between those taking estrogen plus progestin therapy and those taking placebo [19]. In the largest study of the role of hormones in OA, Cirillo and colleagues [20] used another definition of OA, that is, a total joint replacement because of OA. They found that women taking estrogen replacement therapy in the Women’s Health Initiative were about 15% less likely to require total knee or hip arthroplasty than those not taking such therapy (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.70–1.00), but that estrogen combined with progestin therapy was not associated with the risk of joint replacement. Sowers and colleagues [21] reported that women in the lowest tertile of estradiol were almost twice as likely as those in the highest tertile to undergo knee replacement.

Race/ethnicity

The prevalence of OA and the patterns of joints affected by OA vary among racial and ethnic groups. Both hip and hand OA were much less frequent among Chinese subjects in the Beijing Osteoarthritis Study [22,23] than in whites in the Framingham Study, but Chinese women in the Beijing Osteoarthritis Study [24] had a significantly higher prevalence of both radiographic and symptomatic knee OA than white women in the Framingham Study. Radiographic hip OA has been reported to be rare in African blacks, but the first NHANES and the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project have shown that hip OA is at least as common in African Americans as in whites [25,26]. Whether some of these racial/ethnic differences are related to differences in anatomic femoral and acetabular features, shown to be important in radiographic hip OA in whites [27], is worthy of further study.

Genetics

Results from several studies have shown that OA is inherited and may vary by joint site. Twin and family studies have estimated the heritable component of OA to be between 50% and 65%, with larger genetic influences for hand and hip OA than for knee OA [28–30]. This topic is discussed in detail in other articles in this issue.

Congenital/developmental conditions

A few congenital or developmental abnormalities (ie, congenital subluxation, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis) have been associated with the occurrence of hip OA in later life [31–33]; however, because these developmental deformities are uncommon, they probably only account for a small proportion of the hip OA in the general population. Several studies have examined subclinical acetabular dysplasia, a more common, milder developmental abnormality, in relation to hip OA, with conflicting results [27,34–37]. More recently, Lane and colleagues [27] reported that abnormal center-edge angle or acetabular dysplasia were associated with an approximately threefold increased risk of incident hip OA in women, suggesting that subclinical acetabular dysplasia may be a significant risk factor for the development of hip OA.

Diet

Dietary factors are the subject of considerable interest in OA, but results of studies are conflicting. As discussed earlier, the effects of risk factors may vary according to the incidence and progression of OA and by definitions of radiographic features of OA and symptomatic OA. In 1996, McAlindon and colleagues [38] reported that the risk of progressive knee OA was threefold greater for subjects in the lowest (<27 ng/mL) and middle (27.0–33.0 ng/mL) tertiles of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D than for subjects in the highest tertile; however, no such effect was observed for the risk of incident disease. In the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, women in the middle (23–29 ng/mL) and lowest (8–22 ng/mL) tertiles of serum 25-vitamin D were three times more likely to develop incident hip OA, defined by joint-space narrowing, than those in the highest tertile (30–72 ng/mL). Serum vitamin D levels, however, were not associated with the risk of hip OA characterized by osteophytes or with new disease defined according to the summary grade [39]. More recently, data from two cohort studies failed to confirm a protective effect of vitamin D on the structural worsening of knee OA [40]. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health is underway to examine whether this vitamin can affect knee symptoms and cartilage loss measured on MRI in established knee OA.

Low dietary intake of vitamin C was associated with an increased risk of progression, but not incidence, of radiographic knee OA and knee symptoms among the participants in the Framingham Study. In men, vitamin E intake was associated inversely with knee OA progression, but this association was not statistically significant [41]. Using serum biomarkers of antioxidant status, Jordan and colleagues [42] reported that the relative frequencies of isoforms of tocopherols might be important in OA, showing that subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project who had a high ratio of alpha:gamma tocopherol were 50% less likely to have radiographic knee OA. In the same study, those in the highest tertile of serum lutein and beta-cryptoxanthine also were less likely to have radiographic knee OA [43]. Subjects who had low levels of selenium, another anti-oxidant measured in toenails, were more likely to have radiographic knee OA, bilateral knee OA, and severe knee OA [44]. A recent controlled clinical trial of vitamin E, however, failed to ameliorate symptoms in patients who had symptomatic knee OA or to prevent the progression of knee OA, as measured by cartilage volume on MRI [45].

In one study, high levels of serum vitamin K were associated with a low prevalence of radiographic hand OA and particularly for the presence of large osteophytes [46]. The relation of serum vitamin K levels to radiographic knee OA is less clear. A recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin K supplementation (phylloquinone, 500 μg/d) did not confirm a protective effect of vitamin K on the severity of radiographic hand OA.

Local risk factors

Obesity

Obesity and overweight have long been recognized as potent risk factors for OA, especially OA of the knee [1]. The results from the Framingham Study found that women who had lost about 5 kg had a 50% reduction in the risk of new symptomatic knee OA [47]. The same study also demonstrated that weight loss was strongly associated with a reduced risk of development of radiographic knee OA. Weight-loss interventions have been shown to decrease pain and disability in established knee OA [48,49]. The Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial showed that weight loss combined with exercise, but neither weight loss nor exercise alone, was effective in decreasing pain and improving function in obese elders who had symptomatic knee OA [48]. In a recent meta-analysis of weight loss in OA, Christensen [49] concluded that function could improve with a decrease in weight of about 5%, but the effects of weight loss on pain were less consistent.

The relationship between overweight and hip OA is inconsistent and, if it exists, is weaker than with knee OA [25,50]. There is, however, more consistent evidence that obesity increases the risk of bilateral radiographic or symptomatic hip OA [51]. In the Nurses’ Health Study, higher body mass index, especially body mass index at age 18 years, was strongly associated with an increased risk of total hip replacement therapy for hip OA [52]. Increased loading on the joint probably is the main, but not the only, mechanism by which obesity causes knee or hip OA. Overloading the knee and hip joints could lead to cartilage breakdown and failure of ligamentous and other structural support.

Injury/surgery

Significant injury to the structures of a joint, particularly a transarticular fracture, meniscal tear requiring meniscectomy, or anterior cruciate ligament injury, can result in a significantly increased risk of future OA and musculoskeletal symptomatology [53,54].

Occupation

Repetitive use of joints at work is associated with an increased risk of OA. Studies have found that farmers have a high prevalence of hip OA [55]. The prevalence of Heberden’s nodes was much higher in cotton mill workers, whereas spinal OA was no more common in these workers than in controls [56]. Workers whose jobs required repeated pincer grip had significantly more OA at distal interphalangeal joints than did workers whose job required power grip [57].

In the Framingham Study, the risk of developing knee OA was more than two times greater for men whose jobs required both carrying and kneeling or squatting in mid-life than for those whose jobs did not require these physical activities [58]. Coggon and colleagues [59] further indicated that the risks of knee OA associated with kneeling and squatting were higher among persons who were overweight or whose job also involved lifting.

Physical activity/sports

Studies examining the relationship between sports activities and subsequent OA have produced conflicting results. There is some evidence that elite long distance runners are at high risk for the development of knee and hip OA [60–62]; and elite soccer players are at higher risk of developing knee OA than are non–soccer players [61,63]. Surprisingly, the general level of physical activity itself also may increase the risk of OA. In the Framingham Study, physical activity among elderly subjects generally was characterized by leisure-time walking and gardening. Persons who engaged in relatively high levels of such activity had a threefold greater risk of developing radiographic knee OA than sedentary persons within 8 years of follow-up [64]. Similar findings also were reported in another study in which women who had a high lifetime level of physical activity had a high prevalence of hip OA [65]. In contrast, others have shown that, in the absence of acute injury, recreational (moderate) long distance running and jogging did not seem to increase the risk of OA [66,67].

Mechanical factors

The relationship between muscle strength and OA is complex, may vary by joint site, and is not entirely understood. Muscle weakness and atrophy commonly associated with knee OA had been thought to be the product of disuse resulting from pain avoidance. Slemenda and colleagues [68], however, noted that even women who had asymptomatic radiographic knee OA and no muscle atrophy had quadriceps muscle weakness, suggesting that this weakness might be a risk factor for the development of symptomatic knee OA [69]. Baker and colleagues [69] also confirmed that among men and women who did not have knee symptoms, persons who had both patellofemoral and tibiofemoral radiographic knee OA had weaker quadriceps strength than those who did not have OA. Furthermore, the results from a longitudinal study suggested that quadriceps muscle weakness not only resulted from painful knee OA but also was itself a risk factor for structural damage to the joint [70,71]. In contrast, Sharma and colleagues [70] showed that greater quadriceps muscle strength in the setting of malalignment and laxity actually might be associated with an increased risk of knee OA progression [72].

In hand OA, Dominick and colleagues [73] reported inverse cross-sectional associations between grip strength and OA of the carpometacarpal joint and between pinch strength and OA of the metacarpophalangeal joint in a subset of individuals in the Genetics of Generalized Osteoarthritis Study, a study of familial OA. In the Framingham Study, however, greater grip strength was associated with an increased risk of radiographic hand OA. Adjusting for age, physical activity, and occupation, men whose maximal grip strength was in the highest tertile had a threefold increased risk of OA in the proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, or thumb-base joints, as compared with those with grip strength in the lowest tertile [74]. The authors suggested that the maximal force exerted on specific joints might influence development of OA in those joints.

Alignment

Knee alignment (ie, the hip-knee-ankle angle) is a key determinant of load distribution, and any shift from a neutral or collinear alignment of the hip, knee, and ankle affects load distribution at the knee. Therefore, one would speculate that malaligned knees might have a higher risk of developing OA and a higher subsequent risk of progression than knees with neutral alignment.

In a prospective cohort study, Sharma and colleagues [75] demonstrated that in the presence of existing knee OA, abnormal anatomic alignment was associated strongly with accelerated structural deterioration in the compartment under greatest compressive stress. Knees with varus alignment at baseline had a fourfold increase in the odds of medial progression of knee OA, and those with valgus alignment at baseline had a nearly fivefold increase in the odds of lateral progression. The same study also found that the impact of varus or valgus malalignment on the risk of OA progression was greater in knees with more severe baseline radiographic disease than in knees with mild or moderate disease [76]. Another study found that knee malalignment was associated with the size and progression of bone marrow lesions as well as with rapid cartilage loss on MRI [77].

The association between malalignment and risk of incident knee OA is less clear, however. The results from the Rotterdam study found that among knees with Kellgren-Lawrence grade 0 and 1 OA, knees with valgus alignment had a 54% increased risk and knees with varus alignment had a twofold increased risk for the development of radiographic knee OA compared with normally aligned knees [78]. In the Framingham Study, however, Hunter and colleagues [79], using four measures of knee joint alignment (ie, the anatomic axis, the condylar angle, the tibial plateau angle, and the condylar tibial plateau angle), found none of these measures to be associated with an increased risk of incident radiographic knee OA. The authors speculated that malalignment might not be a primary risk factor for the occurrence of radiographic knee OA but rather a marker of disease severity and/or its progression [79].

Laxity

Knee laxity is another potential risk factor for knee OA. Results from a cross-sectional study found that varus-valgus knee laxity is greater in the nonarthritic knees of patients who have idiopathic disease than in the knees of controls, suggesting that a portion of the increased laxity of knee OA precedes disease development and may predispose the patient to developing disease [80]. Others have reported that sagittal plane or anterior-posterior laxity may be increased in persons who have mild OA, and anterior-posterior laxity seems to decline with increasing severity of knee OA [81,82]. Because knee laxity may be altered by the disease itself, longitudinal data will be helpful to confirm these relationships.

Another factor that can alter biomechanics at the knee and hip is inequality in leg length. In the first population-based study of this issue, persons in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project who had a leg-length inequality of at least 2 cm were almost twice as likely as persons with legs of equal length to have radiographic knee OA and were 40% more likely to have knee symptoms [83].

Risk factors for symptomatic osteoarthritis

Although symptomatic knee OA is common, causes substantial disability, and consumes tremendous medical resources, most previous studies have focused on the risk factors for radiographic OA [1]. Not all risk factors for radiographic OA are strong predictors of joint symptoms [1,2]. Women who had radiographic knee OA were more likely to have symptoms than men [84], and African Americans generally reported more knee and hip symptoms than whites [85]. People who had severe radiographic OA were more likely to report joint pain than those who had milder radiographic abnormalities2 [9]. Strenuous physical activity, especially activities requiring kneeling, knee-bending, squatting, or prolonged standing [64,86], as well as knee injury and trauma [87], also have been linked to a high prevalence of symptomatic knee OA.

A few studies have demonstrated that several morphologic and pathologic changes in the knee detected by MRI (ie, bone marrow lesions [88,89], synovitis [90,91], effusion [90], or periarticular lesions [92]) were associated with knee pain, but others have failed to confirm the association between bone marrow lesions and knee pain [93].

Studying risk factors for symptomatic OA is challenging. Although pain in OA long has been considered chronic, it is not necessarily constant. Clinically, physicians often notice that patients who have OA experience episodes of recurrent pain or pain exacerbation over the course of the disease. The pain from OA often worsens with use of the involved joints and lessens or is relieved with rest. Such pain patterns also are observed in epidemiologic studies. Recently, Gooberman-Hill and colleagues [94] reported that joint pain among subjects who had knee or hip OA often was intermittent and variable, and adaptation and avoidance strategies modified the experience of pain. Because of methodologic and logistical difficulties, however, few studies have been conducted to examine the dynamic relationship between risk factors and pain fluctuation. One such study used weekly telephone interviews over 12 weeks to assess the impact of fluctuations in knee or hip pain. Fluctuations were frequent, observed in about 49% of individuals; decreases in pain were associated with improved function and with decreased work absenteeism, sleep disruption, and health care resource use [95].

Summary

Evolving definitions of OA and improvements in risk factor measurement that use advanced imaging, systemic and local biomarkers, and improved methods for measuring symptoms and their impact can help elucidate mechanisms and identify potential areas for intervention or prevention. The application of these new sources of knowledge about the OA process holds promise for the development of new, potentially disease-modifying pharmaceuticals and nonpharmacologic therapies.

References

- 1.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(8):635–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(8):1343–55. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199808)41:8<1343::AID-ART3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadler NM. Knee pain is the malady—not osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(7):598–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-7-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(3):351–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFrances CJ, Podgornik MN. National Hospital Discharge Survey. Adv Data. 2004;2006(371):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellgren J, Lawrence J. Atlas of standard radiographs. The epidemiology of chronic rheumatism. Vol. 2. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman RD, Bloch DA, Dougados M, et al. Measurement of structural progression in osteoarthritis of the hip: the Barcelona consensus group. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(7):515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Conrozier T, et al. Which is the best radiographic protocol for a clinical trial of a structure modifying drug in patients with knee osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(6):1308–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernborg JS, Nilsson BE. The natural course of untreated osteoarthritis of the knee. Clin Orthop. 1977;(123):130–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahlback S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968;277(Suppl):7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannan MT, Felson DT, Pincus T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(6):1513–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Reed JI, et al. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(8):1134–41. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy L, Schwartz T, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 doi: 10.1002/art.24021. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, et al. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(9):769–81. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wluka AE, Cicuttini FM, Spector TD. Menopause, oestrogens and arthritis. Maturitas. 2000;35(3):183–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hannan MT, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, et al. Estrogen use and radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee in women. The Framingham osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(4):525–32. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Lane NE, et al. Association of estrogen replacement therapy with the risk of osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(18):2073–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevitt MC, Felson DT, Williams EN, et al. The effect of estrogen plus progestin on knee symptoms and related disability in postmenopausal women: the heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(4):811–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<811::AID-ANR137>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cirillo DJ, Wallace RB, Wu L, et al. Effect of hormone therapy on risk of hip and knee joint replacement in the women’s health initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3194–204. doi: 10.1002/art.22138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sowers MR, McConnell D, Jannausch M, et al. Estradiol and its metabolites and their association with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2481–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nevitt MC, Xu L, Zhang YQ, et al. Very low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis among Chinese elderly in Beijing compared to Caucasians in the U.S: the Beijing Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1773–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang YQ, Xu L, Nevitt MC, et al. Chinese have a much lower prevalence of radiographic osteoarthritis of the hand than Caucasians in the U. S Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(9):2065–71. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2065::AID-ART356>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Xu L, Nevitt MC, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis between the elderly Chinese population in Beijing and whites in the United States: the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(9):2065–71. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2065::AID-ART356>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tepper S, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with hip osteoarthritis: data from the first national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES-I) Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(10):1081–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, et al. Prevalence of hip pain, radiographic hip osteoarthritis, severe radiographic hip osteoarthritis, and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;47:S212. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane NE, Lin P, Christiansen L, et al. Association of mild acetabular dysplasia with an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis in elderly white women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(2):400–4. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<400::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spector TD, Cicuttini F, Baker J, et al. Genetic influences on osteoarthritis in women: a twin study. BMJ. 1996;312(7036):940–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7036.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palotie A, Vaisanen P, Ott J, et al. Predisposition to familial osteoarthrosis linked to type II collagen gene. Lancet. 1989;1(8644):924–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felson DT, Couropmitree NN, Chaisson CE, et al. Evidence for a Mendelian gene in a segregation analysis of generalized radiographic osteoarthritis: the Framingham study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(6):1064–71. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1064::AID-ART13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38(455):810–24. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stulberg SD, Cooperman DR, Wallensten R. The natural history of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(7):1095–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;(213):20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, et al. Osteoarthritis of the hip and acetabular dysplasia. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(5):308–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.5.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith RW, Egger P, Coggon D, et al. Osteoarthritis of the hip joint and acetabular dysplasia in women. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(3):179–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.3.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau EM, Lin F, Lam D, et al. Hip osteoarthritis and dysplasia in Chinese men. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(12):965–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.12.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Cooper C, et al. Acetabular dysplasia and osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly white women. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(10):627–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.10.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAlindon TE, Felson DT, Zhang Y, et al. Relation of dietary intake and serum levels of vitamin D to progression of osteoarthritis of the knee among participants in the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(5):353–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lane NE, Gore LR, Cummings SR, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and incident changes of radiographic hip osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):854–60. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<854::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felson DT, Niu J, Clancy M, et al. Low levels of vitamin D and worsening of knee osteoarthritis: results of two longitudinal studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):129–36. doi: 10.1002/art.22292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAlindon TE, Jacques P, Zhang Y, et al. Do antioxidant micronutrients protect against the development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(4):648–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordan JM, De Roos AJ, Renner JB, et al. A case-control study of serum tocopherol levels and the alpha- to gamma-tocopherol ratio in radiographic knee osteoarthritis: the Johnston county osteoarthritis project. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):968–77. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Roos AJ, Arab L, Renner JB, et al. Serum carotenoids and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: the Johnston county osteoarthritis project. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(5):935–42. doi: 10.1079/phn2001132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jordan JM, Fang F, Arab L, et al. Selenium levels are associated with increased risk for osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):s455. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wluka AE, Stuckey S, Brand C, et al. Supplementary vitamin E does not affect the loss of cartilage volume in knee osteoarthritis: a 2 year double blind randomized placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neogi T, Booth SL, Zhang YQ, et al. Low vitamin K status is associated with osteoarthritis in the hand and knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1255–61. doi: 10.1002/art.21735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, et al. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(7):535–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-7-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the arthritis, diet, and activity promotion trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1501–10. doi: 10.1002/art.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, et al. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):433–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Saase JL, Vandenbroucke JP, van Romunde LK, et al. Osteoarthritis and obesity in the general population. A relationship calling for an explanation. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(7):1152–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heliovaara M, Makela M, Impivaara O, et al. Association of overweight, trauma and workload with coxarthrosis. A health survey of 7,217 persons. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(5):513–8. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Aweh GN, et al. Total hip replacement due to osteoarthritis: the importance of age, obesity, and other modifiable risk factors. Am J Med. 2003;114(2):93–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, et al. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3145–52. doi: 10.1002/art.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roos EM, Ostenberg A, Roos H, et al. Long-term outcome of meniscectomy: symptoms, function, and performance tests in patients with or without radiographic osteoarthritis compared to matched controls. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(4):316–24. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, et al. Osteoarthritis of the hip and occupational activity. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992;18(1):59–63. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lawrence JS. Rheumatism in cotton operatives. Br J Ind Med. 1961;18:270–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.18.4.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hadler NM, Gillings DB, Imbus HR, et al. Hand structure and function in an industrial setting. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21(2):210–20. doi: 10.1002/art.1780210206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Felson DT, Hannan MT, Naimark A, et al. Occupational physical demands, knee bending, and knee osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham study. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(10):1587–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coggon D, Croft P, Kellingray S, et al. Occupational physical activities and osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(7):1443–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1443::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puranen J, Ala-Ketola L, Peltokallio P, et al. Running and primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br Med J. 1975;02(5968):424–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5968.424-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kujala UM, Kettunen J, Paananen H, et al. Knee osteoarthritis in former runners, soccer players, weight lifters, and shooters. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(4):539–46. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spector TD, Harris PA, Hart DJ, et al. Risk of osteoarthritis associated with long-term weight-bearing sports: a radiologic survey of the hips and knees in female ex-athletes and population controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(6):988–95. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roos H, Lindberg H, Gardsell P, et al. The prevalence of gonarthrosis and its relation to meniscectomy in former soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(2):219–22. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McAlindon TE, Wilson PW, Aliabadi P, et al. Level of physical activity and the risk of radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham study. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):151–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lane NE, Hochberg MC, Pressman A, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly women. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):849–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lane NE, Michel B, Bjorkengren A, et al. The risk of osteoarthritis with running and aging: a 5-year longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(3):461–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Newton PM, Mow VC, Gardner TR, et al. Winner of the 1996 Cabaud award. The effect of lifelong exercise on canine articular cartilage. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):282–7. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Slemenda C, Brandt KD, Heilman DK, et al. Quadriceps weakness and osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(2):97–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baker KR, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Very low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis among Chinese elderly in Beijing compared to Caucasians in the U.S. : the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(6):1815–21. doi: 10.1002/art.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Slemenda C, Heilman DK, Brandt KD, et al. Reduced quadriceps strength relative to body weight: a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(11):1951–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199811)41:11<1951::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brandt KD, Heilman DK, Slemenda C, et al. Quadriceps strength in women with radiographically progressive osteoarthritis of the knee and those with stable radiographic changes. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(11):2431–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharma L, Dunlop DD, Cahue S, et al. Quadriceps strength and osteoarthritis progression in malaligned and lax knees. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(8):613–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dominick KL, Jordan JM, Renner JB, et al. Relationship of radiographic and clinical variables to pinch and grip strength among individuals with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1424–30. doi: 10.1002/art.21035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chaisson CE, Zhang Y, Sharma L, et al. Grip strength and the risk of developing radiographic hand osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(1):33–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<33::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharma L, Song J, Felson DT, et al. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2001;286(2):188–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cerejo R, Dunlop DD, Cahue S, et al. The influence of alignment on risk of knee osteoarthritis progression according to baseline stage of disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(10):2632–6. doi: 10.1002/art.10530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Felson DT, McLaughlin S, Goggins J, et al. Bone marrow edema and its relation to progression of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(5 Pt 1):330–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_1-200309020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brouwer GM, van Tol AW, Bergink AP, et al. Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1204–11. doi: 10.1002/art.22515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hunter DJ, Niu J, Felson DT, et al. Knee alignment does not predict incident osteoarthritis: the Framingham osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1212–8. doi: 10.1002/art.22508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sharma L, Lou C, Felson DT, et al. Laxity in healthy and osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):861–70. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<861::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wada M, Imura S, Baba H, et al. Knee laxity in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(6):560–3. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.6.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brage ME, Draganich LF, Pottenger LA, et al. Knee laxity in symptomatic osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(304):184–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Golightly YM, Allen KD, Renner JB, et al. Relationship of limb length inequality with radiographic knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(7):824–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, et al. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(8):914–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, et al. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston county osteoarthritis project. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):172–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maetzel A, Makela M, Hawker G, et al. Osteoarthritis of the hip and knee and mechanical occupational exposure—a systematic overview of the evidence. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(8):1599–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM, et al. The association of knee injury and obesity with unilateral and bilateral osteoarthritis of the knee. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130(2):278–88. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Felson DT, Chaisson CE, Hill CL, et al. The association of bone marrow lesions with pain in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(7):541–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Felson DT, Niu J, Guermazi A, et al. Correlation of the development of knee pain with enlarging bone marrow lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):2986–92. doi: 10.1002/art.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hill CL, Gale DG, Chaisson CE, et al. Knee effusions, popliteal cysts, and synovial thickening: association with knee pain in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(6):1330–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hill CL, Hunter DJ, Niu J, et al. Synovitis detected on magnetic resonance imaging and its relation to pain and cartilage loss in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(12):1599–603. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hill CL, Gale DR, Chaisson CE, et al. Periarticular lesions detected on magnetic resonance imaging: prevalence in knees with and without symptoms. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2836–44. doi: 10.1002/art.11254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Link TM, Steinbach LS, Ghosh S, et al. Osteoarthritis: MR imaging findings in different stages of disease and correlation with clinical findings. Radiology. 2003;226(2):373–81. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2262012190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gooberman-Hill R, Woolhead G, Mackichan F, et al. Assessing chronic joint pain: lessons from a focus group study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):666–71. doi: 10.1002/art.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hutchings A, Calloway M, Choy E, et al. The longitudinal examination of arthritis pain (LEAP) study: relationships between weekly fluctuations in patient-rated joint pain and other health outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(11):2291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]