Abstract

Rationale: Major pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) registries report a greater incidence of PAH in women; mutations in the bone morphogenic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) occur in approximately 80% of patients with heritable PAH (hPAH).

Objectives: We addressed the hypothesis that women may be predisposed to PAH due to normally reduced basal BMPR-II signaling in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs).

Methods: We examined the BMPR-II signaling pathway in hPASMCs derived from men and women with no underlying cardiovascular disease (non-PAH hPASMCs). We also determined the development of pulmonary hypertension in male and female mice deficient in Smad1.

Measurements and Main Results: Platelet-derived growth factor, estrogen, and serotonin induced proliferation only in non-PAH female hPASMCs. Female non-PAH hPASMCs exhibited reduced messenger RNA and protein expression of BMPR-II, the signaling intermediary Smad1, and the downstream genes, inhibitors of DNA binding proteins, Id1 and Id3. Induction of phospho-Smad1/5/8 and Id protein by BMP4 was also reduced in female hPASMCs. BMP4 induced proliferation in female, but not male, hPASMCs. However, small interfering RNA silencing of Smad1 invoked proliferative responses to BMP4 in male hPASMCs. In male hPASMCs, estrogen decreased messenger RNA and protein expression of Id genes. The estrogen metabolite 4-hydroxyestradiol decreased phospho-Smad1/5/8 and Id expression in female hPASMCs while increasing these in males commensurate with a decreased proliferative effect in male hPASMCs. Female Smad1+/− mice developed pulmonary hypertension (reversed by ovariectomy).

Conclusions: We conclude that estrogen-driven suppression of BMPR-II signaling in non-PAH hPASMCs derived from women contributes to a pro-proliferative phenotype in hPASMCs that may predispose women to PAH.

Keywords: estrogen, sex, pulmonary hypertension, bone morphogenic protein type II, proliferation

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Women develop pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) more frequently that men, and decreased bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) signaling is associated with the development of PAH.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our research shows that pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from women without PAH demonstrate depressed BMPR-II signaling, and these effects may predispose cells to proliferation and be mediated by estrogens. Our research suggests that differential BMPR-II signaling may account for the increased frequency of PAH observed in women.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a devastating disease characterized by severe pulmonary arterial remodeling and occlusive pulmonary vascular lesions, leading to right ventricular failure. Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) normally exhibit low rates of proliferation, migration, and apoptosis to maintain a low-resistance pulmonary circulation. However, alterations in key signaling pathways, including the BMPR-II pathway, can lead to abnormal cell growth and remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature. Heterozygous germ-line mutations in the gene (BMPR2) encoding the bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) occur in up to 80% of families with PAH and are found in approximately 20% of patients with sporadic PAH (1). The majority of BMPR2 mutations cause haploinsufficiency and, thus, reduced cell surface levels of BMPR-II (2).

BMPR-II belongs to the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor superfamily (3). Signaling by BMPs requires the formation of heterodimeric complexes of the constitutively active type II receptor, BMPR-II, and a corresponding type 1 receptor. After BMP ligand-induced heteromeric complex formation, the type II receptor kinase phosphorylates the type I receptor, which in turn phosphorylates Smad1/5/8 (R-Smads) to propagate the signal into the cell. Phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 forms heteromeric complexes with Smad4 (Co-Smad), which then translocate to the nucleus and associate with other transcription factors to regulate the expression of numerous genes.

The inhibitor of DNA binding family of proteins (Id proteins) are major downstream mediators of BMP signaling. These proteins bind to the ubiquitously expressed E protein family members with high affinity and inhibit their binding to target DNA. Id1 and Id3 are major targets of BMP signaling in PASMCs, and induction of both is dependent on intact BMPR-II (4). In particular, Id3 regulates PASMC cell cycle (4), suggesting BMP signaling via Id genes in the regulation of PASMC proliferation, loss of which likely contributes to the abnormal growth of vascular cells in PAH. Furthermore, reduced phospho-Smad1 levels and Id gene levels have been observed in lung tissues from patients with idiopathic and heritable PAH (5), and it was recently shown that mice with targeted deletion of Smad1 in the pulmonary endothelium develop PAH (6).

Major PAH registries report a greater incidence of PAH in women (7, 8). Indeed, altered estrogen metabolism has been implicated in the increased penetrance in female patients with PAH harboring a BMPR-II mutation (8–10). In addition, estrogen has been shown to decrease BMPR-II signaling via the estrogen receptor 1 (11). Aromatase (CYP19A1), a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily, synthesizes estrogens through the aromatization of androgens. We recently demonstrated that isolated human PASMCs (hPASMCs) and the medial layer of intact pulmonary arteries express aromatase and that expression was greatest in female hPASMCs. Indeed, inhibition of aromatase protects female mice and rats from developing experimental pulmonary hypertension (PH) by restoring BMPR-II signaling (12). These observations confirm that there are sex differences in cell-cycle regulation (13), and we hypothesized that fundamental differences exist in the activity of BMP signaling pathways in male and female non-PAH hPASMCs that may favor proliferation in female PASMCs and predispose women to PAH. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (14, 15).

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the online supplement.

Non-PAH hPASMCs

The peripheral human non-PAH PASMCs were isolated by microdissection from peripheral segments of artery (0.3–1.0 mm external diameter) from macroscopically normal tissue removed from control patients undergoing pneumonectomy with no reported presence of PAH, as previously described (5). Proliferation studies were performed as previously described (5). See online supplement for details.

Small Interfering RNA Transfection in PASMCs

Synthetic small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting human BMPRII, SMAD1, and Id3 (20 nmol/L) were used for targeted gene knockdown in male hPASMCs as described previously (4). See online supplement for details.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

At necropsy, lung tissue from each rodent was removed and snap frozen. Messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in lung and hPASMCs was assessed by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction as described previously and in the online supplement (16).

Immunoblotting

Protein expression was assessed in mouse whole lung and hPASMCs as described previously and in the online supplement (16).

Smad1+/− Mice

Smad1 conditional knockout mice were generated using the Cre-loxP system (17). Age- and sex-matched wild-type (WT) littermates were studied as controls. Methods for isolating PASMCs from Smad1+/− mice are described in the online supplement.

Hemodynamic Measurements

Heart rate, right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP), and systemic arterial pressure were measured and analyzed as previously described (16, 18) and in the online supplement.

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

Right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) in mice was assessed by weight measurement of the right ventricular free wall and left ventricle plus septum. The ratio expressed is RV/LV + S.

Lung Histopathology

Lung sagittal sections (3 μm) were stained with α-smooth muscle actin (<80 μm external diameter) and microscopically assessed for degree of muscularization in a blinded fashion, as previously described (19) and in the online supplement.

Bilateral Ovariectomy

To investigate the role of ovarian hormones in the development of PH, we ovariectomized WT and Smad1+/− mice at 8 to 10 weeks of age as previously described (20) and in the online supplement.

Measurement of 17β-Estradiol Concentrations

Circulating 17β-estradiol levels were quantified in mouse plasma samples by ELISA (Estradiol ELISA; Life Technologies, Paisley, UK).

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc analyses and Student’s unpaired t test (as indicated in figure legends) to determine significance of differences. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Proliferation of Male versus Female hPASMCs

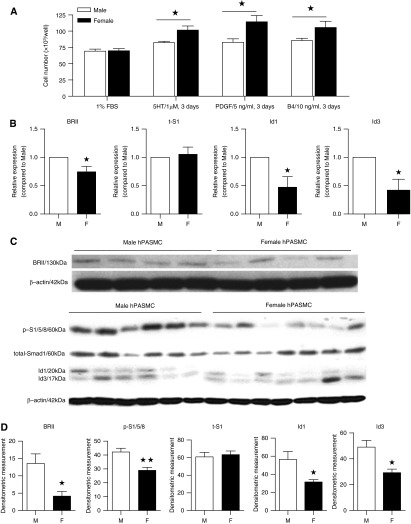

Female non-PAH hPASMCs proliferated consistently to serotonin (1 μM), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (5 ng/ml), and BMP4 (10 ng/ml). In contrast, male cells exhibited no significant proliferation to these mitogens (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Proliferation and bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) signaling in male (M) and female (F) non–pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). (A) Female cells were more proliferative than male cells in response to 3 days of administration of serotonin (5HT), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and bone morphogenetic protein 4 (B4) compared with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) control. (B) Female cells had significantly lower basal levels of BMPR-II (BRII), Id1, and Id3 messenger RNA after 48 hours in 0.1% FBS. (C) Representative immunoblots. (D) Female hPASMCs express significantly lower basal levels of BRII, phospho-Smad 1/5/8 (p-S1/5/8), Id1, and Id3 protein. ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01 versus male (n = 4–7, repeated two to three times per isolate). Student’s unpaired t test with two-tailed distribution. 5-HT/1 μM; PDGF/5 ng/ml, BMP4/10 ng/ml for 3 days unless stated otherwise.

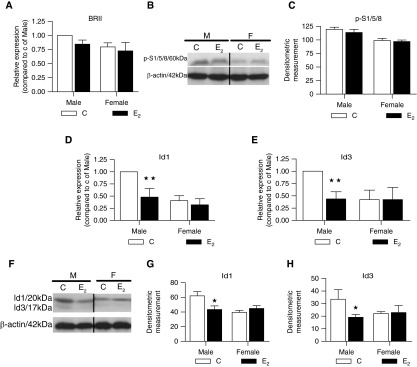

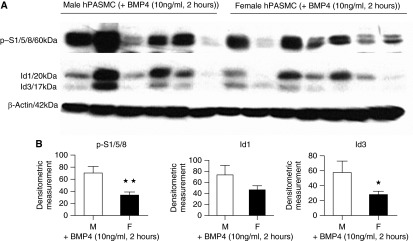

BMPR-II Signaling in Male versus Female hPASMCs

BMPR-II, Id1, and Id3 mRNA transcripts were significantly decreased in female hPASMCs compared with male (Figure 1B). Protein levels of BMPR-II, pSmad1/5/8, Id1, and Id3 were also lower in female hPASMCs compared with male (Figures 1C and 1D) (we confirm these observations in later figures using different cohorts of cells; see Figures 6 and 8). Stimulation with BMP4 resulted in a significantly lower induction of pSmad1/5/8 and Id3 in female hPASMCs than male hPASMCs (Figures 2A and B).

Figure 6.

Effects of 17β-estradiol (E2, 1 μM) on bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) signaling in male (M) and female (F) non–pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). (A) E2 had no effect on BMPR2 (BRII) messenger RNA (mRNA) expression (n = 4). (B) Representative Western blot for phospho-Smad1/5/8 (p-S1/5/8). (C) E2 had no effect on p-Smad1/5/8 protein expression (n = 3). (D, E) In male cells, E2 significantly reduced the levels of Id1 and Id3 mRNA (n = 4). (F–H) In male cells, E2 significantly reduced the levels of Id1 and Id3 protein resulting in expression levels similar to those observed in female (n = 3). Expression levels were quantified by densitometry. ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01 versus vehicle control (C) (n = 4). All isolates were repeated two to three times.

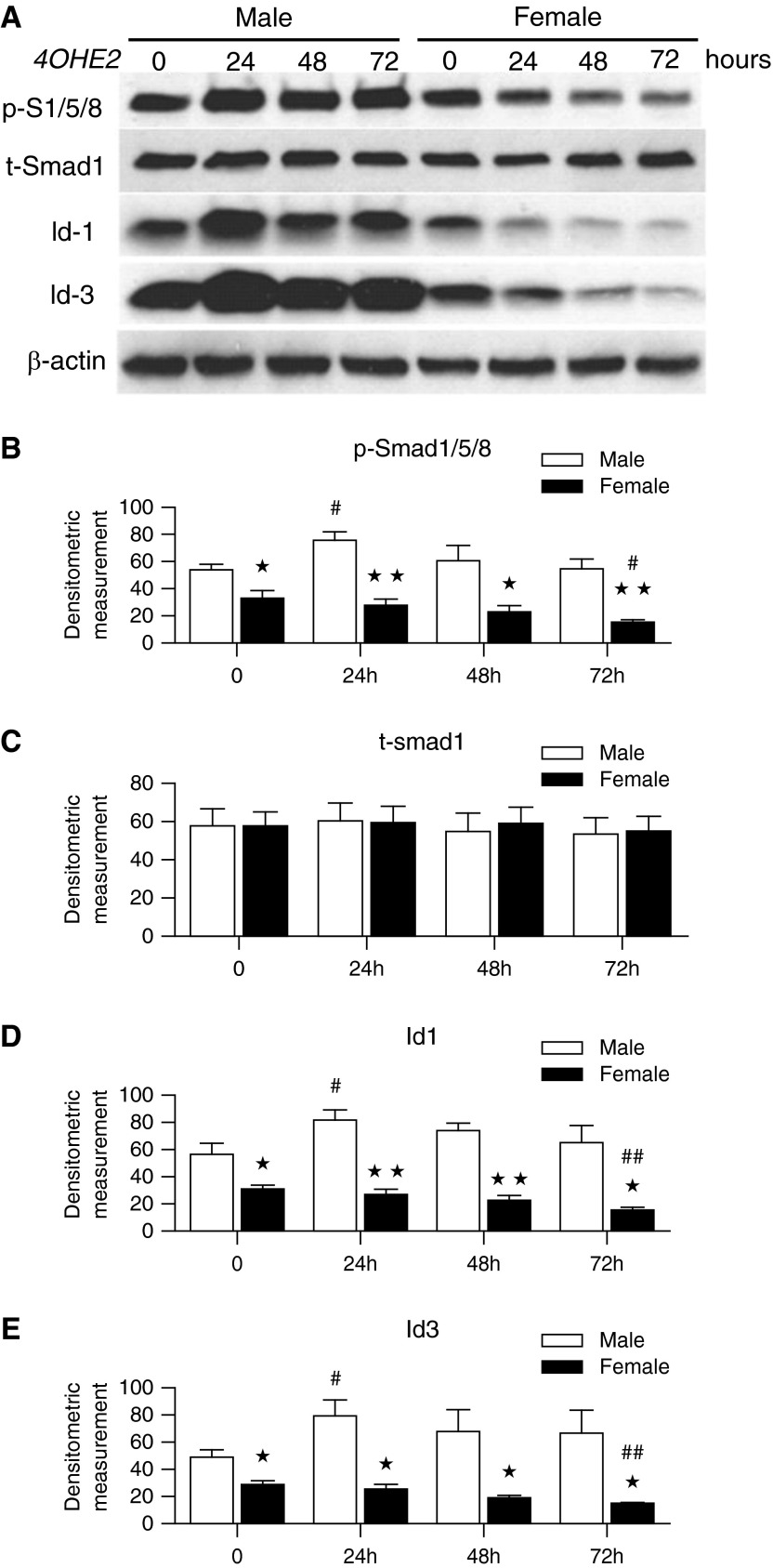

Figure 8.

Differential effect of 4-hydroxyestradiol (4OHE2) in male and female non–pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). (A) Representative Western blots for phospho-Smad1/5/8 (p-S1/5/8), Id1, and Id3 in male and female hPASMCs. p-S1/5/8, Id1, and Id3 expression was lower in female hPASMCs than male hPASMCs, and 4OHE2 increased expression of these in male hPASMCs while reducing expression in female hPASMCs. Densitometric analysis of protein for p-S1/5/8 (B), total-Smad1 (t-Smad1) (C), Id1 (D), and Id3 (E) (n = 4, all isolates repeated two to three times). The expression levels were quantified by densitometry. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus baseline (0); ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01 versus male. Student’s unpaired t test with two-tailed distribution.

Figure 2.

Effect of bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) stimulation on bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) signaling in male (M) and female (F) non–pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). Western blot analysis demonstrates that female PASMCs had significantly lower BMP4-stimulated protein levels of phospho-Smad1/5/8 (p-S1/5/8) and Id3 after 2-hour treatment with BMP4 (10 ng/ml). (A) Representative Western blot. (B) Expression levels quantified by densitometry. ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01 versus male; n = 6 (M) and n = 7 (F), all isolates repeated two to three times. Student’s unpaired t test with two-tailed distribution.

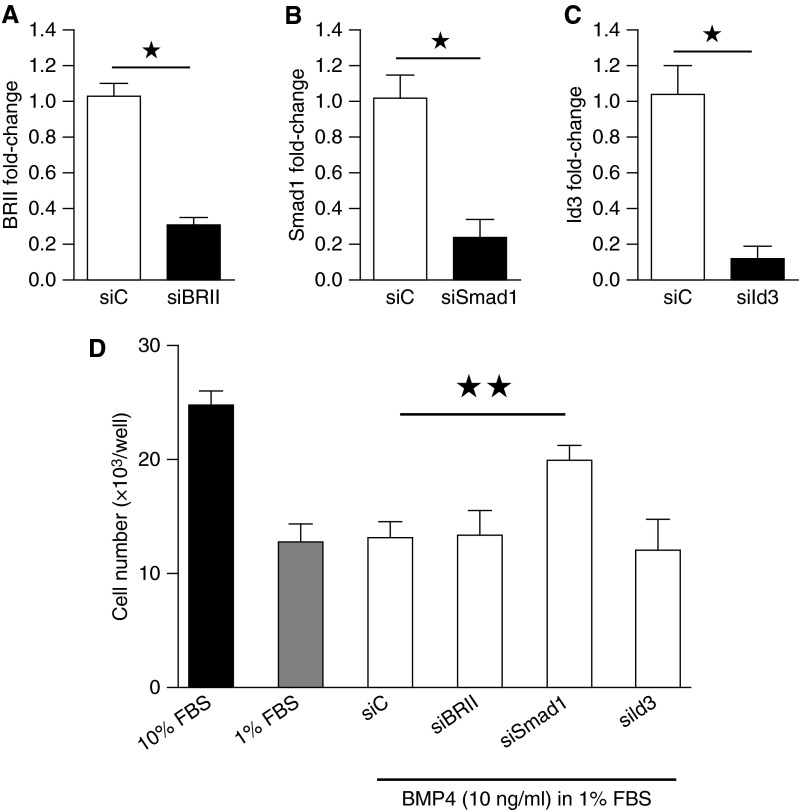

Effect of the BMPR-II/Id Axis on Proliferation in Male PASMCs

To examine further the role of the BMPR-II/Id axis on proliferation to BMP4, we silenced BMPR-II, SMAD1, and Id3 (as it regulates PASMC cell cycle [4]) using siRNA (Figures 3A–3C). Although the siRNA control, BMPR-II, and Id3 had no effect, silencing of Smad1 enabled male hPASMCs to proliferate to BMP4 (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Proliferation in male non–pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs) after knockdown of bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BRII) signaling. (A–C) Knockdown of BMPR-II (siBRII), Smad1 (siSmad1), and Id3 (siId3) by small interfering RNA (siRNA) in male hPASMCs. (D) Male hPASMCs do not normally proliferate to BMP4; however, proliferation to BMP4 (open bars) was restored after knockdown of Smad1 (n = 3). ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01, Student’s unpaired t test with two-tailed distribution. FBS = fetal bovine serum; siC = siRNA control.

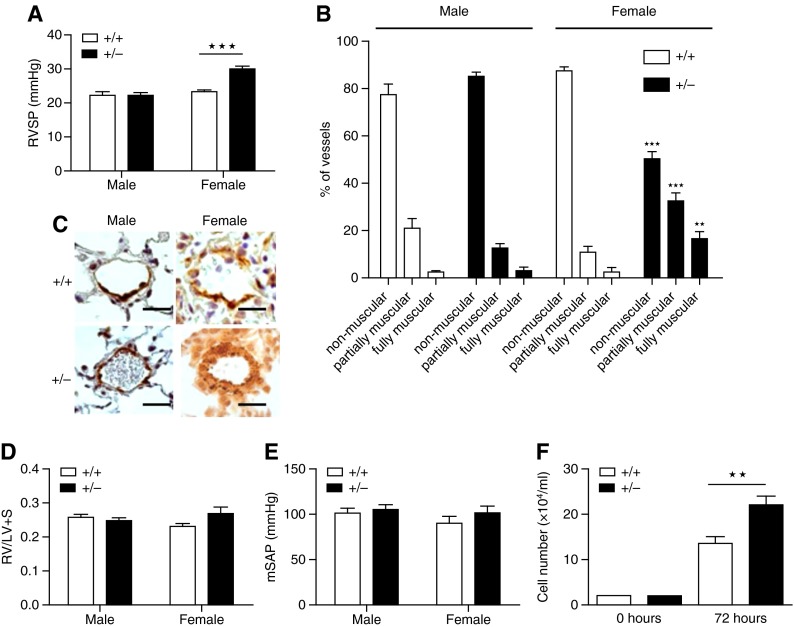

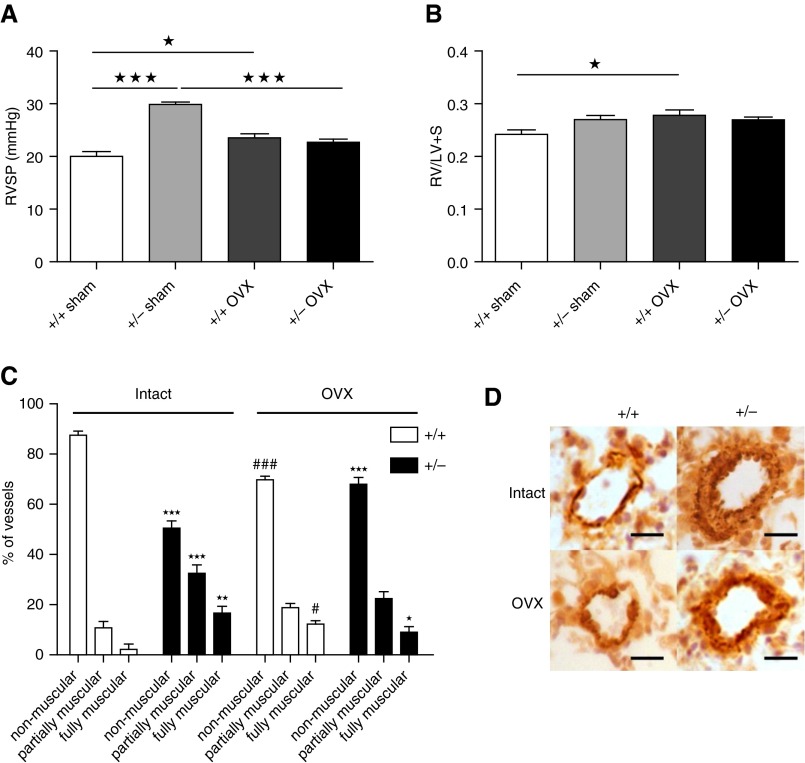

Female Smad1+/− Mice Spontaneously Develop PH

We examined sex differences in the development of spontaneous PH in Smad1+/− mice at 5 to 6 months, as we have previously shown that PH in transgenic mice can be age related and the PH phenotype can take 5 to 6 months to emerge (21). Female Smad1+/− mice developed PH, whereas the male mice did not (Figure 4). Female Smad1+/− mice display significantly elevated RVSP and pulmonary vascular remodeling compared with male mice (Figures 4A–4C). No significant difference in RV hypertrophy or systemic blood pressure was observed between the groups (Figures 4D and 4E). PASMCs isolated from female Smad1+/− mice proliferated faster than those of female WT mice (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Development of pulmonary hypertension in Smad1 heterozygous knockout mice (+/−) compared with wild-type control mice (+/+). +/− mice developed pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) after 6 months of age. (A) Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) is elevated in female +/− mice. n = 6–7. (B) Small pulmonary vessels were assessed for degrees of circumferential α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)–positive staining, indicative of muscularization. Vessels were classified as nonmuscular (no α-SMA–positive immunoreactivity), partially muscular, or fully muscularized. There was a decrease in nonmuscular vessels and an increase in muscularized vessels in the female +/− mice. n = 3–4. (C) Resistance of pulmonary arterial wall thickness (as measured by α-SMA [dark brown/orange] staining) was increased in female +/− mice. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. (D, E) There were no differences in the right ventricular hypertrophy (right ventricular free wall and left ventricle plus septum [RV/LV + S]) (+/+, n = 6–8; +/−, n = 5) and mean systemic arterial pressure (mSAP) in +/+ versus +/− mice (n = 6). (F) PASMCs from female +/− mice were more proliferative than cells from female +/+ mice (n = 3–4). ★★P < 0.01, ★★★P < 0.001 versus +/+, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc analyses.

To define the role of female sex hormones in the susceptibility of female Smad1+/− mice, mice were subjected to sham or ovariectomy surgery. Lack of female sex hormones was confirmed by the decreased uterine weight (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). Ovariectomy attenuated the elevated RVSP observed in female Smad1+/− mice (Figure 5A). Ovariectomy itself slightly increased RVSP and RVH in WT mice (Figures 5A and 5B). Ovariectomy also attenuated the increase in pulmonary vascular remodeling observed in the Smad1+/− mice (Figures 5C and 5D).

Figure 5.

Effect of ovariectomy (OVX) or sham operation (sham) on development of pulmonary hypertension in Smad1 heterozygous knockout mice (+/−) compared with wild-type control mice (+/+). (A) Effect of OVX on right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). (B) Effect of OVX on right ventricular hypertrophy (right ventricular free wall and left ventricle plus septum [RV/LV + S]) (n = 6–8). (C, D) Small pulmonary vessels were assessed for degrees of circumferential α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)–positive (dark brown/orange) staining, indicative of muscularization. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. Vessels were classified as nonmuscular (no α-SMA–positive immunoreactivity), partially muscular, or fully muscularized. OVX attenuated the increase in the number of muscularized pulmonary arteries observed in the +/− mice (n = 3–4). ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01, ★★★P < 0.001 versus +/+, #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 versus +/+ intact, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc analyses.

The BMPR-II Signaling Axis Is Down-regulated in Female Mouse Lung

Smad1 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in both male and female Smad1+/− mice compared with WT animals (Figure E2A). Female WT mice display significantly lower basal levels of Smad1 mRNA in lungs than male WT mice, and Smad1 mRNA expression was lower in female Smad1+/− mice than male Smad1+/− mice (Figure E2A). Further investigation revealed that the mRNA levels of BMPR-II and Id3 were also significantly lower in female mice than male mice (Figures E2B and E2C). Plasma estrogen (E2) levels were not affected by Smad1 deficiency (Figure E2D). There was an equal expression of aromatase and CYP1B1 mRNA and protein in the lungs of both Smad1+/− mice and WT mice (Figures E2E–E2G). Liver and kidney tissues from these animals were also assessed, and no sex differences in BMPR-II, Smad1, Id1, or Id3 mRNA were observed in these tissues (Figure E3).

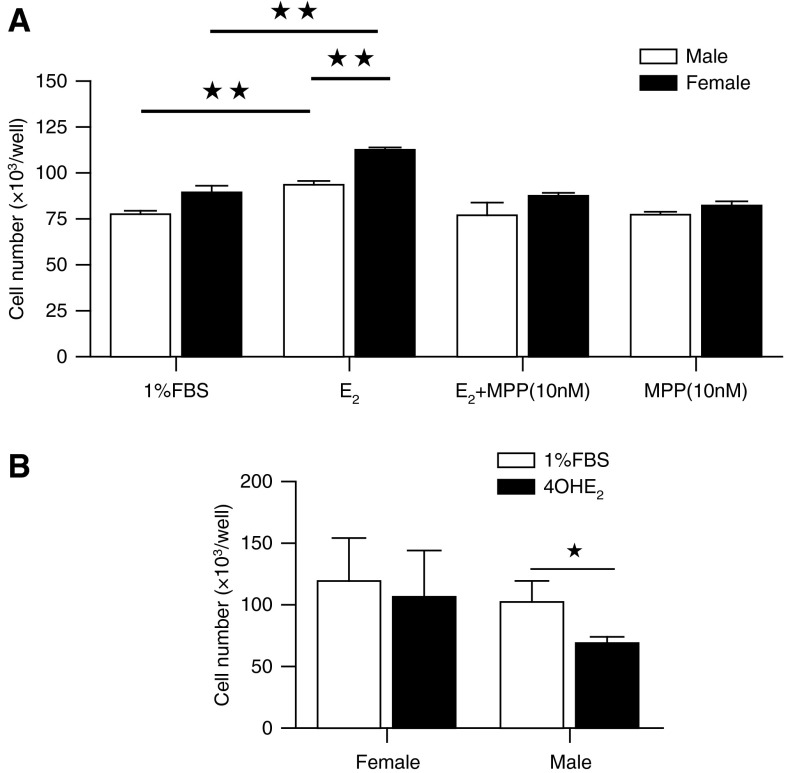

Effect of Estrogen on BMPRII/Smad/Id Axis in hPASMCs

Stimulation of hPASMCs with estrogen had no effect on BMPR-II mRNA or pSmad1/5/8 protein expression in male or female PASMCs (Figures 6A–6C). Estrogen did, however, significantly down-regulate both Id1 and Id3 transcript and protein levels in male PASMCs (Figures 6D–6H). pERK2 expression (not pERK1) was elevated in female hPASMCs compared with in male hPASMCs (Figures E4A and E4B). We investigated the expression of CYP1B1 as well as catechol-O-methyl transferase, the enzyme that metabolizes 4- and 2- hydroxyestradiol (OHE) metabolites to methoxy-metabolites. Expression levels of these enzymes were equal in male and female hPASMCs (Figure E4B).

Effect of Estrogen Metabolites on BMPRII/Smad/Id Axis in hPASMCs

Estrogen induced proliferation of hPASMCs (Figure 7A). The proliferative response to estrogen was greatest in female hPASMCs and inhibited by the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) antagonist MPP (Figure 7A). ERβ and GPER antagonists have no effect on estrogen-induced proliferation (data not shown). 4OHE2 is a major product of CYP1B1, and its effects on hPASMCs have not previously been reported. 4OHE2 did not cause proliferation in female hPASMCs but caused a decrease in proliferation in male cells (Figure 7B). To investigate these differences further, we examined the influence of 4OHE2 on BMPR-II signaling. In line with its differential effect on proliferation in male and female hPASMCs, it had a differential effect on BMPR-II signaling in male and female hPASMCs. In male hPASMCs, consistent with its antiproliferative effect, it induced an increase in the expression of pSmad1/5/8, Id1, and Id3, whereas in female hPASMCs it reduced these (Figures 8A–8E).

Figure 7.

Proliferation to 17β-estradiol (E2, 0.1 μM) in non–pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). (A) E2 induced more proliferation in female hPASMCs than male cells (n = 4), and E2-induced proliferation was abolished by the ERα-antagonist MPP. ★★P < 0.01 versus 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS)/male. (B) 4-hydroxyestradiol (4OHE2) (0.1 mM) decreased proliferation male hPASMCs only (n = 4, all isolates repeated two to three times). ★P < 0.05, Student’s unpaired t test with two-tailed distribution.

Discussion

In hPAH families, penetrance of PAH in BMPR-II mutation carriers is low (20–30%), suggesting other risk factors must influence the emergence of the PAH phenotype. Of all known risk factors, the risk of developing PAH in families with BMPR-II mutations is affected most by sex, with the occurrence of PAH being approximately threefold higher in women than men (22). Polymorphisms in the aromatase gene associated with increased estradiol production have also been associated with increased risk of portopulmonary hypertension in patients with liver disease (23). We also recently provided evidence that endogenous estrogen may be a causative factor in PAH and may suppress endogenous BMPR-II signaling axis (12). Thus, in the present study we addressed the ensuing hypothesis that, even before being exposed to any PAH risk factor, women may be predisposed to PAH due to reduced basal BMPR-II signaling in their hPASMCs.

Serotonin, PDGF, and BMP4 are all ERK-dependent mitogens in the pulmonary circulation (24–26), and, under the conditions used, all could induce proliferation in female hPASMCs but not male cells. Loss of BMPR-II can reduce the antiproliferative influence of Smad signaling and can allow unopposed pro-proliferative ERK1/2 signaling (27). Hence, we interrogated sex differences in the BMPR-II signaling pathway and pERK expression. Compared with male cells, cohorts of non-PAH female hPASMCs expressed significantly reduced levels of BMPR-II, Id1, and Id3 mRNA levels as well as significantly lower protein levels of BMPR-II, pSmad1/5/8, Id1, and Id3. pERK2 expression was, however, higher in female hPASMCs compared with male hPASMCs. As pERK2 has a positive role in controlling cell proliferation (28, 29), this observation is consistent with the proliferative phenotype of female hPASMCs. This is also consistent with previous findings showing that BMP4-induced Id expression is negatively regulated by ERK1/2 activation (27). Given the antiproliferative nature of BMPR-II–mediated Smad signaling in hPASMCs (30), the reduced expression of this axis may predispose female PASMCs to the pro-proliferative effects of persistent pERK signaling. Indeed, BMPR-II signaling can prevent PDGF-induced proliferation of hPASMCs (25). Hence, the reduced BMPR-II/Smad/Id gene signaling in female hPASMCs may contribute to the increased proliferation of female cells in response to mitogens. Stimulation of female hPASMCs with BMP4 resulted in a markedly reduced activation of pSmad1/5/8 and Id3 compared with male. Furthermore, in female hPASMCs, the addition of BMP4 results in proliferation, whereas no proliferation was observed in male hPASMCs. We knocked down BMPR-II, Smad1, and Id3 in male hPAMSCs to investigate if this could induce a more proliferative “female” phenotype. Knockdown of Smad1 alone reversed the nonproliferative phenotype in the male cells. This is consistent with differential regulation of Smad1. Indeed, it has recently been reported that Smad1 can be differentially regulated by modifiers, including BMPR-II itself (31).

These finding suggest that the reduction in Smad1 results in an altered phenotype in male cells, inducing a pro-proliferative phenotype similar to that observed in female cells. These results may suggest that increasing BMPR-II signaling in female PASMCs may reduce a proliferative phenotype. Consistent with this, we show here that proliferation is reduced in PASMCs derived from female Smad+/+ mice compared with PASMCs with reduced Smad1 derived from Smad+/− mice. In vivo, we have shown that the BMPR-II signaling pathway is reduced in the lungs of mice with PH but that decreasing endogenous estrogen synthesis restores this signaling pathway and reverses PH (12). We have also previously shown that that rescue of BMPR-II signaling with ataluren reduces the hyperproliferative phenotype of pulmonary artery endothelial and smooth muscle cells derived from patients with PAH (32).

Only female Smad1+/− mice demonstrated elevated RVSP and increased pulmonary vascular remodeling. We have previously studied normoxic female mice that develop PH (mice overexpressing the serotonin transporter [SERT+ mice], overexpressing mts1 [S100A4], or dosed with dexfenfluramine) and have shown that such normoxic mice do not develop RVH despite elevated RSVP and pulmonary vascular remodeling (20, 33–35). This suggests that under normoxic conditions, the mouse right ventricle is resistant to hypertrophy in the face of moderate RVSP elevation. Consistent with this, the female Smad1+/− mice did not develop RVH. The levels of Smad1 mRNA in both male and female Smad1+/− mice were reduced by 50% compared with their WT counterparts. Neither BMPR-II nor Id3 mRNA expression was affected by the reduction of Smad1. However, in both WT and Smad1+/− mice, BMPR-II, Smad1, and Id3 expression were all expressed at lower levels in the female lung than the male lung. This down-regulation of the BMPR-II axis was confined to the lung, as no significant sex differences were observed in liver or kidney. Smad1 expression was most markedly reduced in the female Smad1+/− mice. We suggest that in female Smad1+/− mice, Smad1 expression in the lung has decreased below a threshold required for the normal functioning of the BMPR-II pathway and thus predisposing PASMCs from female Smad1+/− to a proliferative phenotype resulting in the onset of PH in these animals. Consistent with this, PASMCs from female Smad1+/− mice proliferated significantly more than PASMCs from female WT mice.

In the female Smad1+/− mice, we demonstrate that the PH phenotype (RVSP and vascular remodeling) is markedly reduced after ovariectomy. There was an increase in RVSP, RVH, and vascular remodeling in ovariectomized female WT mice. This does suggest that in absence of other risk factors, sex hormones can be protective against vascular and ventricular changes consistent with previous studies. Indeed, estrogen has recently been shown to be protective against hypoxic-induced PAH in male rats (36), and progesterone can protect against monocrotaline-induced PAH (37).

Serotonin has been implicated in the PH observed in the SERT+ mouse (38), hypoxic rodents (38–40), the sugen/hypoxic rodent (41), and dexfenfluramine-treated female mice (18). In these models, estrogen plays a causative role in the development of PH. For example, in SERT+ mice the major circulating estrogen 17β-estradiol can restore the PH phenotype in ovariectomized SERT+ mice (35). 17β-Estradiol can also induce proliferation of hPASMCs and may therefore contribute to the pulmonary artery remodeling observed in PAH (16, 35). In addition, endogenous estrogen plays a key role in the development of PH in female hypoxic mice and in the female sugen/hypoxic rat (12). We have also previously demonstrated that CYP1B1 can influence the development of PH in animal models (16, 20). Plasma estrogen levels were unaffected by Smad1 deficiency in the Smad1+/− mice. However, we confirmed that there is aromatase and CYP1B1 expression in the lungs of the mice used in this study, and this is unaffected by Smad1 knockdown, allowing the possibility that intact local estrogen synthesis and metabolism to active metabolites may influence BMPR-II signaling in the lungs of these mice. 17β-Estradiol induced proliferation of female, but not male, hPASMCs in an ERα-dependent fashion. Consistent with this, we have previously demonstrated that the ERα-antagonist MPP can reverse hypoxia-induced PH in female but not male mice, and this therapeutic effect is associated with an increase in BMPR-II and Id1 expression (12). Stimulation of hPASMCs with 17β-estradiol had no effect on BMPR-II or pSmad1/5/8 expression in males or females. In male cells, 17β-estradiol did, however, significantly reduce the levels of Id1 and Id3 at both the mRNA and protein level, while having no effect on female hPASMCs. These findings suggest that estrogen down-regulates Id1 and Id3 expression. The lack of effect in female cells may be because Id1 and Id3 levels are already significantly reduced in these cells. Although there was no effect of acute administration of 17β-estradiol on BMPR-II and pSmad1/5/8 expression, there was decreased expression of these proteins in female hPASMCs. This may be via epigenetic silencing, as it has been shown that SMAD1 can be epigenetically silenced through aberrant DNA methylation and such an effect could be mediated by estrogen (42, 43). The average age of the patients from whom the cells were derived was 65 years for the male cells and 61 years for the female cells. Hence, these were age-matched. However, as the average age of menopause in the UK is 51 years, this means that all the women were postmenopausal. In a recent study, however, we examined the expression of aromatase in hPASMCs from men and women of a similar average age as those studied here. We demonstrated that cells derived from postmenopausal women expressed 12-fold higher levels of aromatase than PASMCs derived from men of a similar age (12). This suggests that female hPASMCs can synthesize more estrogen than male cells. Therefore, we believe that endogenous local estrogen production influences BMPR-II signaling.

Consistent with this, we have previously shown in mouse whole lung that inhibition of estrogen production by anastrozole can significantly elevate Id1 and Id3 levels in females but not males, indicating that in an in vivo setting local vascular estrogen may be responsible for the reduced levels of Id1 and Id3 observed in female subjects (12).

We have previously shown in PH models that increased CYP1B1-mediated estrogen metabolism may lead to the formation of mitogens, including 16α-hydroxyestrone (16). Sex did not influence CYP1B1 or catechol-O-methyl transferase expression, suggesting that all hPASMCs have the potential to metabolize estrogen to 4- and 2-OHE metabolites. We examined 4OHE2 further, as this metabolite is one of the major products of CYP1B1 activity and has been shown to be mutagenic in breast epithelial cells and pro-proliferative in human ovarian cancer cells (44, 45). Although 4OHE2 had no proliferative effect in female hPASMCs, it inhibited proliferation in male hPASMCs. We were interested to determine if these differential effects were due to changes in BMPR-II signaling. We present the novel observation that 4OHE2 increased expression of pSmad 1/5/8, Id1, and Id3 in male hPASMCs but decreases the expression of pSmad 1/5/8, Id1, and Id3 further in female hPASMCs. The results suggest that locally derived estrogen metabolites such as 4OHE2 can exert differential effects on BMPR-II signaling and cell proliferation, which may contribute to sex differences in proliferation.

One of the limitations of this study is the availability of age-matched samples from non-PAH hPASMCs from men and women with no cardiovascular disease. However, we have countered these limitations by repeating experiments in each sample two to three times. In addition, our observation that BMPR-II signaling is depressed in female hPASMCs was reproducible across separate experiments depicted in Figures 1, 6, and 8. In addition the in vivo studies confirm the observation across species (Figure E2).

We conclude that female hPASMCs have decreased BMPR-II signaling compared with male hPASMCs and that estrogenic-driven suppression of BMPR-II signaling may contribute to a pro-proliferative phenotype in female hPASMCs predisposing women to PAH.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

Smad1+/− mice were obtained as a generous gift from the late Dr. Anita Roberts.

Footnotes

Supported by British Heart Foundation (BHF) programme grants RG/11/7/28916 (M.R.M.) and RG/13/4/30107 (N.W.M.) and BHF project grant RG/11/7/28916 (M.R.M.). E.W. is a Medical Research Council (UK)-funded Ph.D. student.

Author Contributions: Involvement in the conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study: K.M.M., N.W.M., and M.R.M. Acquisition of the data or the analysis and interpretation of such information: K.M.M., X.D.Y., L.L., K.W., E.W., M.-A.E., C.K.D., N.W.M., and M.R.M. Writing the article or substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission: K.M.M., N.W.M., and M.R.M.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1802OC on January 21, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Machado RD, Eickelberg O, Elliott CG, Geraci MW, Hanaoka M, Loyd JE, Newman JH, Phillips JA, III, Soubrier F, Trembath RC, et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S32–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Lane KB, Morgan NV, Wheeler L, Phillips JA, III, Newman J, Williams D, Galiè N, et al. BMPR2 haploinsufficiency as the inherited molecular mechanism for primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:92–102. doi: 10.1086/316947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35–51. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J, Li X, Li Y, Southwood M, Ye L, Long L, Al-Lamki RS, Morrell NW. Id proteins are critical downstream effectors of BMP signaling in human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L312–L321. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00054.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X, Long L, Southwood M, Rudarakanchana N, Upton PD, Jeffery TK, Atkinson C, Chen H, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Dysfunctional Smad signaling contributes to abnormal smooth muscle cell proliferation in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2005;96:1053–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000166926.54293.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han C, Hong KH, Kim YH, Kim MJ, Song C, Kim MJ, Kim SJ, Raizada MK, Oh SP. SMAD1 deficiency in either endothelial or smooth muscle cells can predispose mice to pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:1044–1052. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.199158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGoon MD, Benza RL, Escribano-Subias P, Jiang X, Miller DP, Peacock AJ, Pepke-Zaba J, Pulido T, Rich S, Rosenkranz S, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: epidemiology and registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D51–D59. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro S, Traiger GL, Turner M, McGoon MD, Wason P, Barst RJ. Sex differences in the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension enrolled in the registry to evaluate early and long-term pulmonary arterial hypertension disease management. Chest. 2012;141:363–373. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin ED, Cogan JD, West JD, Hedges LK, Hamid R, Dawson EP, Wheeler LA, Parl FF, Loyd JE, Phillips JA., III Alterations in oestrogen metabolism: implications for higher penetrance of familial pulmonary arterial hypertension in females. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:1093–1099. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West J, Cogan J, Geraci M, Robinson L, Newman J, Phillips JA, Lane K, Meyrick B, Loyd J. Gene expression in BMPR2 mutation carriers with and without evidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension suggests pathways relevant to disease penetrance. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:45. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin ED, Hamid R, Hemnes AR, Loyd JE, Blackwell T, Yu C, Phillips JA, III, Gaddipati R, Gladson S, Gu E, et al. BMPR2 expression is suppressed by signaling through the estrogen receptor. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3:6. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mair KM, Wright AF, Duggan N, Rowlands DJ, Hussey MJ, Roberts S, Fullerton J, Nilsen M, Loughlin L, Thomas M, et al. Sex-dependent influence of endogenous estrogen in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:456–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0483OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakada D, Oguro H, Levi BP, Ryan N, Kitano A, Saitoh Y, Takeichi M, Wendt GR, Morrison SJ. Oestrogen increases haematopoietic stem-cell self-renewal in females and during pregnancy. Nature. 2014;505:555–558. doi: 10.1038/nature12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mair KM, Long L, Xu DY, Wallace E, Morrell NW, MacLean MR. Female susceptibility to pulmonary arterial hypertension in Smad 1 +/− mice - contribution of the serotonin system [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A5395. [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacLean MR, Xu DY, Mair KM, Wallace E, Long L, Morrell NW. Gender influences the BMPR2 signalling pathway and BMP-induced proliferation in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A5394. [Google Scholar]

- 16.White K, Johansen AK, Nilsen M, Ciuclan L, Wallace E, Paton L, Campbell A, Morecroft I, Loughlin L, McClure JD, et al. Activity of the estrogen-metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 1B1 influences the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2012;126:1087–1098. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.062927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang S, Tang B, Usoskin D, Lechleider RJ, Jamin SP, Li C, Anzano MA, Ebendal T, Deng C, Roberts AB. Conditional knockout of the Smad1 gene. Genesis. 2002;32:76–79. doi: 10.1002/gene.10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempsie Y, Morecroft I, Welsh DJ, MacRitchie NA, Herold N, Loughlin L, Nilsen M, Peacock AJ, Harmar A, Bader M, et al. Converging evidence in support of the serotonin hypothesis of dexfenfluramine-induced pulmonary hypertension with novel transgenic mice. Circulation. 2008;117:2928–2937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keegan A, Morecroft I, Smillie D, Hicks MN, MacLean MR. Contribution of the 5-HT(1B) receptor to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension: converging evidence using 5-HT(1B)-receptor knockout mice and the 5-HT(1B/1D)-receptor antagonist GR127935. Circ Res. 2001;89:1231–1239. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dempsie Y, MacRitchie NA, White K, Morecroft I, Wright AF, Nilsen M, Loughlin L, Mair KM, MacLean MR. Dexfenfluramine and the oestrogen-metabolizing enzyme CYP1B1 in the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:24–34. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White K, Loughlin L, Maqbool Z, Nilsen M, McClure J, Dempsie Y, Baker AH, MacLean MR. Serotonin transporter, sex, and hypoxia: microarray analysis in the pulmonary arteries of mice identifies genes with relevance to human PAH. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:417–437. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00249.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loyd JE, Butler MG, Foroud TM, Conneally PM, Phillips JA, III, Newman JH. Genetic anticipation and abnormal gender ratio at birth in familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:93–97. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.1.7599869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts KE, Fallon MB, Krowka MJ, Brown RS, Trotter JF, Peter I, Tighiouart H, Knowles JA, Rabinowitz D, Benza RL, et al. Pulmonary Vascular Complications of Liver Disease Study Group. Genetic risk factors for portopulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced liver disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:835–842. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1472OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dempsie Y, MacLean MR. Pulmonary hypertension: therapeutic targets within the serotonin system. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:455–462. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansmann G, de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, Alvira CM, Guignabert C, Bekker JM, Schellong S, Urashima T, Wang L, Morrell NW, et al. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1846–1857. doi: 10.1172/JCI32503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perros F, Montani D, Dorfmüller P, Durand-Gasselin I, Tcherakian C, Le Pavec J, Mazmanian M, Fadel E, Mussot S, Mercier O, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor expression and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:81–88. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1037OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Davies RJ, Southwood M, Long L, Yang X, Sobolewski A, Upton PD, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Mutations in bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor cause dysregulation of Id gene expression in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: implications for familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2008;102:1212–1221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefloch R, Pouysségur J, Lenormand P. Single and combined silencing of ERK1 and ERK2 reveals their positive contribution to growth signaling depending on their expression levels. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:511–527. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00800-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vantaggiato C, Formentini I, Bondanza A, Bonini C, Naldini L, Brambilla R. ERK1 and ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinases affect Ras-dependent cell signaling differentially. J Biol. 2006;5:14. doi: 10.1186/jbiol38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrell NW, Yang XD, Upton PD, Jourdan KB, Morgan N, Sheares KK, Trembath RC. Altered growth responses of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with primary pulmonary hypertension to transforming growth factor-beta(1) and bone morphogenetic proteins. Circulation. 2001;104:790–795. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.094152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breen MJ, Moran DM, Liu W, Huang X, Vary CP, Bergan RC. Endoglin-mediated suppression of prostate cancer invasion is regulated by activin and bone morphogenetic protein type II receptors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drake KM, Dunmore BJ, McNelly LN, Morrell NW, Aldred MA. Correction of nonsense BMPR2 and SMAD9 mutations by ataluren in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:403–409. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0100OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dempsie Y, Nilsen M, White K, Mair KM, Loughlin L, Ambartsumian N, Rabinovitch M, Maclean MR. Development of pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice over-expressing S100A4/Mts1 is specific to females. Respir Res. 2011;12:159. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLean MR, Deuchar GA, Hicks MN, Morecroft I, Shen S, Sheward J, Colston J, Loughlin L, Nilsen M, Dempsie Y, et al. Overexpression of the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene: effect on pulmonary hemodynamics and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:2150–2155. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127375.56172.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White K, Dempsie Y, Nilsen M, Wright AF, Loughlin L, MacLean MR. The serotonin transporter, gender, and 17β oestradiol in the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:373–382. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahm T, Albrecht M, Fisher AJ, Selej M, Patel NG, Brown JA, Justice MJ, Brown MB, Van Demark M, Trulock KM, et al. 17β-Estradiol attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension via estrogen receptor-mediated effects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:965–980. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1293OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tofovic PS, Zhang X, Petrusevska G. Progesterone inhibits vascular remodeling and attenuates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in estrogen-deficient rats. Prilozi. 2009;30:25–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morecroft I, Pang L, Baranowska M, Nilsen M, Loughlin L, Dempsie Y, Millet C, MacLean MR. In vivo effects of a combined 5-HT1B receptor/SERT antagonist in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:593–603. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morecroft I, White K, Caruso P, Nilsen M, Loughlin L, Alba R, Reynolds PN, Danilov SM, Baker AH, Maclean MR. Gene therapy by targeted adenovirus-mediated knockdown of pulmonary endothelial Tph1 attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1516–1528. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morecroft I, Dempsie Y, Bader M, Walther DJ, Kotnik K, Loughlin L, Nilsen M, MacLean MR. Effect of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 deficiency on the development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:232–236. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252210.58849.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciuclan L, Hussey MJ, Burton V, Good R, Duggan N, Beach S, Jones P, Fox R, Clay I, Bonneau O, et al. Imatinib attenuates hypoxia-induced PAH pathology via reduction in 5-hydroxytryptamine through inhibition of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:78–89. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1028OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang S, Elstrom RL, Tam W, Martin P, Kormaksson M, Banerjee S, Vasanthakumar A, Culjkovic B, Scott DW, Wyman S, et al. Mechanism-based epigenetic chemosensitization therapy of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1002–1019. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez BA, Weng YI, Liu TM, Zuo T, Hsu PY, Lin CH, Cheng AL, Cui H, Yan PS, Huang TH. Estrogen-mediated epigenetic repression of the imprinted gene cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C in breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:812–821. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez SV, Russo IH, Russo J. Estradiol and its metabolites 4-hydroxyestradiol and 2-hydroxyestradiol induce mutations in human breast epithelial cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1862–1868. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seeger H, Wallwiener D, Kraemer E, Mueck AO. Estradiol metabolites are potent mitogenic substances for human ovarian cancer cells. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:383–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]