Abstract

Scope

GABAA receptors are modulated by Sideritis extracts. The aim of this study was to identify single substances from Sideritis extracts responsible for GABAA receptor modulation.

Methods and results

Single volatile substances identified by GC have been tested in two expression systems, Xenopus oocytes and human embryonic kidney cells. Some of these substances, especially carvacrol, were highly potent on GABAA receptors composed of α1β2 and α1β2γ2 subunits. All effects measured were independent from the presence of the γ2 subunit. As Sideritis extracts contain a high amount of terpenes, 13 terpenes with similar structure elements were tested in the same way. Following a prescreening on α1β2 GABAA receptors, a high-throughput method was used for identification of the most effective terpenoid substances on GABA-affinity of α1β2γ2 receptors expressed in transfected cell lines. Isopulegol, pinocarveol, verbenol, and myrtenol were the most potent modifiers of GABAA receptor function.

Conclusion

Comparing the chemical structures, the action of terpenes on GABAA receptors is most probably due to the presence of hydroxyl groups and a bicyclic character of the substances tested. We propose an allosteric modulation independent from the γ2 subunit and similar to the action of alcohols and anesthetics.

Keywords: GABAA receptor, Patch clamp recordings, Terpene, Two-electrode voltage clamp recordings, Volatile odorants

1 Introduction

Odorants are able to stimulate signaling pathways and some of these compounds are known to potentiate GABAA receptors (GABAARs) 1–3. Sideritis species are the basis for evening tea preparations consumed in Mediterranean countries, with their popularity possibly due to the sedative properties of Sideritis extracts 4. The genus Sideritis, however comprises more than 150 species. Tea preparations are predominantly used because of their anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsive, and antioxidative properties 4. One of the sedative pathways of Sideritis may involve GABAARs with extracts potentially causing an enhancement of GABA-gated currents similar to the actions of benzodiazepines.

GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. GABA-induced activation of ionotropic GABAARs leads to hyperpolarization of the membrane due to the influx of Cl− ions into the postsynaptic neuron in the adult brain. GABAARs are not only expressed in a wide variety of neurons in various brain regions, e.g. cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and olfactory bulb, but also in non-neuronal cells and peripheral tissues. Due to a large repertoire of identified subunits, there could be a huge variability of subunit combinations forming pentameric GABAAR complexes. Most of the heteromeric receptors contain α and β subunits with the α1β2γ2 composition representing the most abundant receptor isoform (around 60% of all GABAARs) in the brain 5. Distinct subunit combinations have been found to either mediate sedative (e.g. α1β2γ2) or anxiolytic effects (e.g. α2β3γ2) or both 6,7. Furthermore, GABAARs are important as they bind anticonvulsants and anesthetics. The binding site for diazepam, a highly potent anticonvulsant drug, has been studied intensively and is localized at the interface of the α and the γ2 subunits.

GABAARs are members of the Cys-loop receptor superfamily, which also includes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR), glycine receptors, and the serotonin receptors (5HT3R). These all share a similar topological organization with a large extracellular N-terminus harboring a conserved disulfide bridge forming the eponymous Cys-loop. The N-terminus carries 10 β-sheets in an Ig-like structural organization and forms the orthosteric binding site, which is located between adjacent subunits of the pentameric receptor complexes 8. Site-directed mutagenesis studies have provided much information about this binding site, as well as binding sites for the many agents that can modulate the function of these receptors 9,10.

Recently, it was shown that these receptors are also a target of volatile odorant extracts 3, and actions on GABAARs were described for substances from the essential oils such as geraniol or linalool 11. A subunit-specific action of fragrant dioxane derivatives was demonstrated on β1-containing GABAARs, providing a novel tool to detect β1-containing neurons e.g. in neurons of the hypothalamus 12.

Odorants bind to odorant receptors at the olfactory epithelium 13, but it is not yet clear how they reach the brain. The axons of the olfactory sensory neurons could send information to second-order neurons in the olfactory bulb or these compounds could simply diffuse through lipid membranes due to their small size and high hydrophobicity 14,15. Diazepam, for example, is able to pass the blood–brain barrier due to its hydrophobic nature 16. An in vivo study has demonstrated that inhalation of essential oil extracted from Abies sachalinensis resulted in much higher concentrations of odorant compounds in the brain when compared to injection into the peritoneum 17. Nevertheless, more detailed studies are required to solve this issue. Another behavioral study with the species Sideritis clandestina demonstrated the anxiolytic and antioxidant potential of plant extracts. Mice that had ad libitum access to S. clandestina tea over a period of 6 weeks showed decreased thigmotaxis time, an enhanced number of entries into a central area, and enhanced levels of reduced glutathione, a marker protein for antioxidant capacity 18.

Here, we have analyzed several odorant compounds originally identified in Sideritis species. Using GC analysis, we were able to show single components of these extracts and tested them separately on α1β2γ2 or α1β2 receptors expressed either in HEK293 cells or in Xenopus oocytes. Some terpenes, and also various terpene-derived compounds potentiated the GABAergic responses. A search for other terpenes with structural similarities revealed 13 additional candidates. A detailed study of the functional effects of these compounds has allowed us to identify, which structural features are important for their modulatory properties.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

GABA ≥ 99%, DMSO ≥ 99.9%, 1-Octen-3-ol ≥ 98%, Carvacrol ≥ 98%, l-Carveol (mixture of cis and trans) ≥ 95%, Isopulegol ≥ 99%, Linalool ≥ 97%, Myrtenol ≥ 95%, trans-Pinocarveol ≥ 96%, (S)-cis-Verbenol ≥ 95%, α-Pinene ≥ 98%, β-Pinene ≥ 99%, β-Caryophyllene ≥ 80%, β-Myrcene ≥ 95%, Caryophyllene oxide ≥ 95%, α-Terpineol ≥ 96%, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). Dichloromethane (DCM) was obtained from Acros (Geel, Belgium) and freshly distilled before use. Reference compounds for GC-analyses were diluted with DCM to an appropriate concentration. Stock solutions of compounds at a concentration of 1 M were prepared using DMSO and dissolved in the appropriate buffer, prior to use. All reservoirs for control and compound application in electrophysiological recordings contained equivalent amounts of DMSO. The solvent showed no effect on GABA-mediated responses up to 0.1% concentration (data not shown).

2.2 GC-MS

2.2.1 Preparation of Sideritis extracts

Extracts containing the volatile fraction of an infusion of Sideritis were prepared as follows: 5 g of crushed plant material was added to 150 mL of boiled water and stirred at 70°C for 1 h. After filtration and cooling to room temperature, the infusion was mixed with 50 mL DCM and the volatile fraction was separated via solvent assisted flavor evaporation 19. After separation, the organic phase was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated using a Vigreux column and microdistillation 20. The extract was reduced to a final volume of 200 μL. Samples of Sideritis arguta, Sideritis condensata, Sideritis stricta, and Sideritis sipylea were extracted and diluted to an appropriate content with DCM, before analyses.

2.2.2 GC-MS

Analyses were performed on a Thermo Trace GC Ultra (Thermo Scientific, S.p.A., Rodano, Italy) coupled with an ITQ 900 IT mass spectrometer. Analytical capillaries used were DB5 and DB-FFAP (J&W Scientific, Fisons Instruments, Mainz, Germany), in the dimension of 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm. The GC temperature program started from initial 40°C, held for 7 min and increasing up to 250°C at a rate of 8°C/min, held for 15 min. Helium was used as carrier gas at constant flow of 0.8 mL/min and the injected sample volume was 2 μL. The temperature was set to 250°C for the transfer line and to 200°C for the ion source. MS detection mode was EI with a current of 70 eV (Full scan, m/z 30–300). Identification of substances was achieved comparing the obtained mass spectra and retention indices in the samples to the spectra of reference substances injected in parallel 21. Separation was performed on two different analytical gas chromatographic phases.

2.3 Electrophysiology

2.3.1 HEK293 cell preparation

HEK293 cells (Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) were grown in Modified Eagle Medium with Earle's Salts (MEM; PAA, Pasching, Austria), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, l-glutamine (200 mM), and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using the Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Rat receptor cDNA (kindly provided by Proffesor W. Sieghart, Vienna) was used to express a receptor composition of α1β2γ2L subunits. The cDNA stoichiometry was 1:1:2 α1β2γ2L to ensure the incorporation of gamma subunits into the receptor complex. To visualize transfected cells, cDNA encoding for green fluorescent protein was cotransfected.

2.3.2 Whole-cell patch clamp technique

Current amplitudes were measured by the patch clamp technique in a whole-cell configuration. Current signals were amplified with an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA, Goettingen, Germany). After transfection (24–48 h), whole-cell recordings from HEK293 cells were performed by application of ligand using a U-tube. The external buffer consisted of 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH; the internal buffer was 120 mM CsCl, 20 mM N(Et)4Cl, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 11 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. Recording pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate capillaries with an open resistance of 3–6 MΩ. Current responses were measured at a holding potential of −60 mV. The ligand GABA was dissolved in extracellular buffer. Substances alone solved in DMSO and diluted in extracellular solution did not elicit a current response (data not shown). Similarly, untransfected cells did neither respond to GABA or to GABA plus modulator (data not shown).

2.3.3 Oocyte preparation

Following surgical preparation of the oocytes from the ovaries of Xenopus laevis, oocytes were isolated by enzymatic digestion at 19°C for 3–4 h with 600–700 U/mL type 2 collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum (CLS 2, Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) dissolved in OR2 solution containing 82.5 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with Tris). Defollicularized oocytes were obtained from the Institute of Cellular and Molecular Physiology (University of Erlangen-Nuernberg, Germany). The cDNAs of rat α1 and β2 GABAA subunits were subcloned into the pSGEM vector. Plasmids encoding for the human α1, β2, and γ2 subunits were provided by Bjarke Ebert, Lundbeck (Valby, Denmark) and directly used for in vitro transcription. The corresponding cRNA was synthesized with the help of a mMessage mMachine T7 RNA polymerase kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), following the manufacturer's protocol. To express a functional GABAAR, 1.2–2.4 ng of a 1:1 mixture of rat α1 and β2 receptor subunit cRNA was injected using a Nanoject II injector (Drummond Scientific, USA). The human α1β2γ2 receptor configuration was expressed by injecting 1.56–3.12 ng of a 1:1:3 mixture of the corresponding cRNA. The oocytes were incubated in ND96 buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) at 16–18°C for 24 h, before use.

2.3.4 Electrophysiological recordings

The oocytes were used after a 24 h incubation period. Activity of GABAARs was measured with the two-electrode voltage clamp technique. Recording pipettes (GB 150F-10, Science Products, Hofheim, Germany) were manufactured with a P97 micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, USA) and filled with 3 M KCl to give a resistance from 0.2–2 MΩ. Oocytes were clamped at −50 mV using a Turbo Tec-03x npi amplifier (npi electronic GmbH, Tamm, Germany) and constantly superfused with ND96 during recording. Current traces were recorded at 300 Hz and filtered at 200 Hz using cell works software.

The concentration for GABA used in these experiments was 1 μM corresponding to an EC5–10, as it has been previously shown that the use of a low GABA concentration is required to observe small effects by the modulators 2,11. Modulators were tested using GABA plus increasing concentrations of compound and with a control (GABA only) response after every compound application. Washout time between measurements was at least 3 min and was prolonged to 6 min for the highest concentrations. To exclude nonspecific measurements, only reversible effects were taken into account. Recordings were repeated with at least three oocytes from two independent batches. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (∼22°C).

2.4 Flexstation experiments

2.4.1 Cell culture and preparation

HEK293 cells were grown on 90 mm tissue culture plates containing DMEM/Glutamax medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. Cells were transiently transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI, 25 kDa, linear, Polysciences, Eppelheim, Germany). For this purpose, 5 μg of human α1 and β2 were diluted together with 10 μg of γ2 subunit DNA in 1 mL of serum-free medium followed by the addition of 90 μL PEI (1 mg/mL). After 10 min incubation at room temperature, the mixture was added dropwise to a 80–90% confluent plate, and incubated for 24 h. Cells were transferred to black 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Stonehouse, UK), which were pretreated with 0.01% Cultrex poly-l-Lysine (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). After an additional 24 h, incubation cells were used for experiments.

2.4.2 Dye loading and compound preparation

Cells were washed twice with FLEX buffer (115 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM D-glucose, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH). A total of 100 μL fluorescent membrane potential (FMP) blue dye (FLIPR Membrane Potential Blue Kit, Molecular Devices, Wokingham, UK) in Flex buffer (dilution 1:1000) was then added to each well. In case of modulation experiments, the appropriate concentrations of the substances were directly added with dye to the plates. The plates containing the transfected cells and the fluorescent dye (± a distinct concentration of modulatory substance) were incubated for 30 min at 37°C before starting the measurement. Then, another plate containing the appropriate GABA concentrations diluted in FLEX buffer was prepared.

2.4.3 Fluorometric assay

Dye-loaded cells (± a distinct concentration of modulatory substance) and the plate containing various GABA concentrations were transferred to the FlexStation II Device (Molecular Devices). Fluorescence measurements were performed using Softmax Pro software. Before GABA was applied, a baseline was recorded for 20 s. Each well was read five times with high PMT adjustment. Fluorescence values were processed using a peak kinetic reduction algorithm.

2.5 Analysis of data

Fluorescence data were normalized and the dose-response curves were generated using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software) with a sigmoidal dose response (variable slope) equation. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad InStat 3.0 (Graphpad Software). Comparisons with control application were made with one-way ANOVA method and Dunnett post hoc test. Within a particular concentration, the Tukey post hoc test was used to determine substance specific effects. p-values of significance were indicated in the appropriate figures and within the text.

3 Results

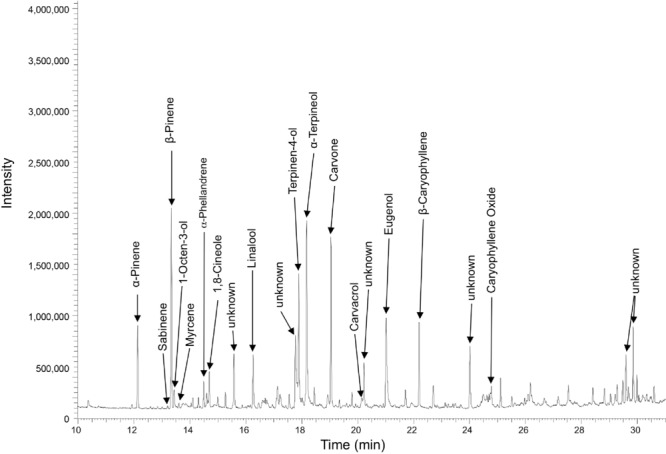

Single components of various Sideritis extracts were analyzed using GC to identify possible candidates for GABAARs modulation (Fig.1). These extracts are rich in terpenes. Specifically, the compounds α- and β-pinene, terpinen-4-ol, α-terpineol, β-caryophyllene and its oxide, sabinene, α-phellandrene, linalool, eugenol, carvone, 1,8-cineole, 1-octen-3-ol, and carvacrol were, among others, found as quantitatively dominant or clearly detectable compounds characteristic for the investigated Sideritis varieties (Fig.1). The following substances were selected for further investigation in physiological studies: α-pinene and β-pinene, sabinene, α-phellandrene, and β-caryophyllene, linalool, 1-octen-3-ol, and carvacrol. Among these candidates are not only pure terpenes and terpene hydroxyl derivatives, but also substances that represent different chemical groups, e.g. 1-octen-3-ol as aliphatic alcohol, β-caryophyllene as sesquiterpene, and carvacrol as monoterpenoid phenol.

Figure 1.

Representative gas chromatographic pattern (GC-flame ionization detector, analytical column DB5) of a Sideritis stricta extract for identification of single substances as candidates for GABAAR modulation.

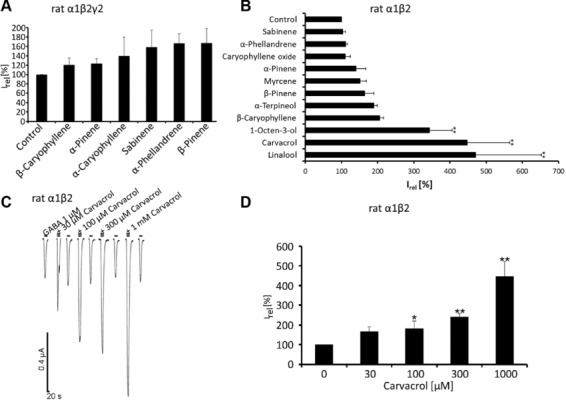

These substances were tested for their potentiating effect on GABA-evoked currents in injected Xenopus oocytes and transfected HEK293 cells expressing α1β2 or α1β2γ2 GABAARs (Fig.2). The presence of the γ2 subunit was tested using a coapplication of Zn2+, which only inhibits α1β2 receptors (data not shown) 22, although recordings from both cell types yielded similar results arguing for an effect independent from the γ2 subunit. Application of compounds in the absence of GABA did not elicit any currents (data not shown). Pinenes had little or no modulatory effects; the current values using high concentrations (1mM) of either α-pinene or β-pinene showed only a small increase in the GABA-evoked responses of 0.35 ± 0.08 μA (compared to 0.25 ± 0.08 μA without α-pinene) and 0.35 ± 0.08 μA (compared to 0.24 ± 0.06 μA without β-pinene), in Xenopus oocytes and 1.37 ± 0.66 nA for α-pinene compared to 1.18 ±. 0.58 nA without modulator, and 0.52 ± 0.16 nA for β-pinene compared to 0.29 ± 0.07 nA for GABA alone in transfected HEK293 cells (Table1; see relative I-values of 1 μM GABA). Similarly, substances such as sabinene, α-phellandrene, and β-caryophyllene did not enhance responses (Fig.2B). A significant potentiation, however, was observed for 1-octen-3-ol, linalool, and carvacrol (Fig.2B). Therefore, carvacrol was tested in a dose-dependent manner using concentrations from 30 μM to 1 mM (Fig.2C). The relative current amplitudes compared to GABA alone showed that carvacrol at concentrations of 100 μM (1.8 fold potentiation) or greater significantly enhanced GABAergic currents (up to 4.5 fold, Fig.2D). Thus, carvacrol was among the substances identified from Sideritis, the most potent modulator on GABAARs comparable to linalool and 1-octen-3-ol (Fig.2B) 11.

Figure 2.

GABAAR modulation by Sideritis components. (A) Comparison of whole-cell currents (Iabs) following GABA (1 μM) application ± Sideritis components especially various pinenes at 1 mM from HEK293 cells expressing rat α1β2γ2 GABAARs. Data are mean current values ± SD, mean Iabs of GABA application alone = 100%, n = number of measured cells; n = 4–8. (B) Similar experiment to (A) but recordings were performed using Xenopus oocytes expressing rat α1β2 GABAARs. GABAergic currents ± single components from Sideritis extract at 1 mM, GABA = 1 μM concentration, n = 4–8 (C) Representative traces following GABA coapplication with the most potent substance carvacrol (range from 30 μM–1 mM). (D) Bar diagram demonstrating the mean current amplitudes for the potentiation of GABAergic currents by different carvacrol concentrations. Mean absolute current values are shown ± SD, n = 3–6. The significance of the depicted currents were compared to control (GABA application alone), **p < 0.01 with Dunnett post hoc test.

Table 1.

Current amplitudes of ionotropic GABAARs modulated by odor substances

| Expressed subunits | Expression system | GABA [μM] | Iabs [μA] | Modulator | GABA + modulator [μM] | Iabs [μA] | Irel [% of 1 μM GABA] | n | Originally identified in Sideritis extract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat α1β2 | Xenopus oocytes | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | α-Phellandrene | 1000 | 0.46 ± 0.08 | 112 ± 19 | 3 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | β-Pinene | 1000 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 134 ± 31 | 7 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | Linalool | 1000 | 1.23 ± 0.25 | 473 ± 96 | 4 | * | ||

| 1 | 1.99 ± 0.64 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 1000 | 6.40 ± 1.74 | 321 ± 87 | 4 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.58 ± 0.13 | Carveol | 600 | 1.71 ± 0.26 | 294 ± 45 | 10 | |||

| 1 | 0.31 ± 0.10 | Pinocarveol | 600 | 1.11 ± 0.32 | 358 ± 103 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | Isopulegol | 600 | 1.25 ± 0.43 | 416 ± 143 | 8 | |||

| 1 | 0.18 ± 0.09 | Carvacrol | 300 | 0.44 ± 0.22 | 414 ± 142 | 5 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.55 ± 0.25 | Myrtenol | 300 | 2.55 ± 1.00 | 463 ± 181 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 0.38 ± 0.16 | Verbenol | 300 | 1.00 ± 0.38 | 263 ± 99 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | α-Pinene | 1000 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 140 ± 32 | 7 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | Myrcene | 1000 | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 147 ± 26 | 7 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1000 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 109 ± 18 | 7 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.052 ± 0.029 | Sabinene | 1000 | 0.057 ± 0.034 | 109 ± 65 | 4 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | β-Caryophyllene | 1000 | 0.085 ± 0.04 | 212 ± 99 | 4 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | α-Terpeniol | 1000 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 177 ± 66 | 3 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | Cedrol | 600 | 1.09 ± 0.18 | 213 ± 35 | 11 | |||

| 1 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | Nerolidol | 600 | 0.73 ± 0.11 | 137 ± 21 | 11 | |||

| 1 | 0.46 ± 0.28 | 2-Methyl-3-buten-2-ol | 600 | 1.19 ± 0.28 | 258 ± 61 | 8 | |||

| 1 | 0.59 ± 0.13 | β-Citronellol | 600 | 0.99 ± 0.18 | 167 ± 30 | 10 | |||

| 1 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | α-Santonin | 600 | 0.57 ± 0.12 | 219 ± 46 | 3 | |||

| 1 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | Theaspiran | 600 | 0.68 ± 0.15 | 219 ± 48 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 0.84 ± 0.27 | α-Thujone | 600 | 0.52 ± 0.20 | 62 ± 24 | 3 | |||

| 1 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | Terpinolene | 600 | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 209 ± 48 | 6 | |||

| 1 | 0.37 ± 0.07 | Myrtenal | 600 | 0.89 ± 0.18 | 240 ± 48.5 | 8 | |||

| 1 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | Nootkatone | 600 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 148 ± 19 | 7 | |||

| Human α1β2γ2 | Xenopus oocytes | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.79 ± 0.25 | Linalool | 300 | 1.69 ± 0.84 | 213 ± 105 | 10 | |||

| 1 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 300 | 0.65 ± 0.11 | 295 ± 50 | 6 | |||

| 1 | 0.13 ± 0.08 | Carveol | 300 | 0.59 ± 0.23 | 453 ± 176 | 8 | |||

| 1 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | Pinocarveol | 300 | 1.67 ± 0.24 | 477 ± 68 | 8 | |||

| 1 | 0.49 ± 0.13 | Isopulegol | 300 | 1.67 ± 0.035 | 340 ± 70 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 1.72 ± 0.64 | Carvacrol | 300 | 3.86 ± 1.46 | 224 ± 85 | 6 | |||

| 1 | 0.35 ± 0.12 | Myrtenol | 300 | 2.58 ± 0.82 | 737 ± 234 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | Verbenol | 300 | 0.89 ± 0.13 | 809 ± 118 | 6 | |||

| Human α1β2γ2 | HEK293 | Iabs [nA] | Iabs [nA] | ||||||

| 1 | 0.51 ± 0.15 | α-Phellandrene | 1000 | 0.83 ± 0.21 | 168 ± 42 | 3 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.29 ± 0.07 | β-Pinene | 1000 | 0.52 ± 0.16 | 179 ± 55 | 4 | * | ||

| 1 | 1.18 ± 0.58 | α-Pinene | 1000 | 1.37 ± 0.66 | 116 ± 56 | 3 | * | ||

| 1 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | Sabinene | 1000 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 156 ± 26 | 6 | * | ||

| 1 | 1.14 ± 0.62 | α-Caryophyllene | 1000 | 1.34 ±0.66 | 117 ± 57 | 7 | * | ||

| 1 | 1.32 ± 0.61 | β-Caryophyllene | 1000 | 1.53 ± 0.69 | 115 ± 52 | 3 | * |

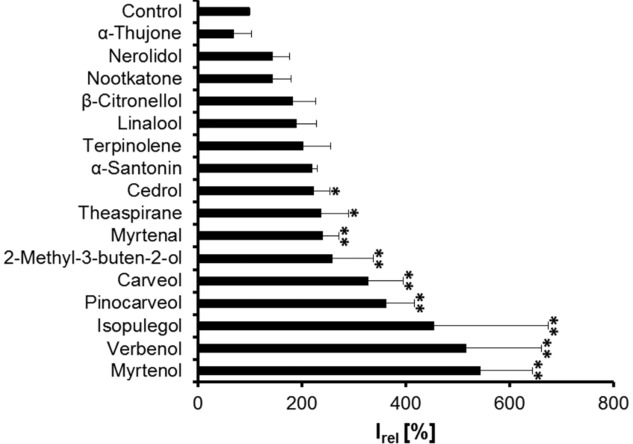

To determine, if there are structural motives within the terpene family that may account for the observed modulatory effects on GABAARs, we probed the effects of 13 structurally related terpenes (Table2). Positive modulation was observed in almost all cases when the substances contained hydroxyl groups, and was enhanced when these substances showed a mono- or bicyclic character (Table1). GABA-evoked responses were significantly potentiated up to 417% by 600 μM isopulegol with Iabs values of 1.25 ± 0.43 μA compared to 0.3 ± 0.04 μA in the absence of the volatile compound (Fig.3, Table1). Less effective were cedrol, theaspirane, myrtenal, 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol, carveol, and pinocarveol, which resulted in 2- to 3.8-fold potentiation (Fig.3, see Table1 for absolute current values). Substances that did not potentiate responses included α-thujone, nerolidol, nootkatone, β-citronellol, terpinolene, and α-santonin, most of which lack a hydroxyl group (Fig.3, Tables1 and 2).

Table 2.

Terpenoid substances and their structural features used to study modulatory effects on GABAARs

| Compound | Occurence | Class/functional group | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Methyl-3-buten-2-ol | Hop | Hemi terpene Hydroxy |  |

| β-Citronellol | Geranium | Acyclic monoterpene Hydroxy |  |

| Terpinolene | Scots pine | Monocyclic monoterpene |  |

| Carveol | Spearmint | Monocyclic monoterpene Hydroxy |  |

| Isopulegol | Lemon eucalyptus | Monocyclic monoterpene Hydroxy |  |

| α-Thujone | Artemisia | Bicyclic monoterpene Ketone |  |

| Myrtenal | Cumin seed | Bicyclic monoterpene Aldehyde |  |

| Pinocarveol | Common gum sed | Bicyclic monoterpene Hydroxy |  |

| Nerolidol | Neroli | Sesquiterpene Hydroxy |  |

| Cedrol | Cedar wood | Sesquiterpene Hydroxy |  |

| α-Santonin | Artemisia | Sesquiterpene Ketone |  |

| Nootkatone | Grapefruit | Sesquiterpene Ketone |  |

| Theaspirane | Wine | Sesquiterpene |  |

Figure 3.

Modulatory effects of terpenoid structures. Currents elicited using two-electrode voltage clamp technique recordings on rat α1β2 expressing oocytes by coapplication of GABA (1 μM) and various terpenoid substances with structural similarities to single components of Sideritis extracts. Substance concentration was 600 μM. Mean current amplitudes compared to GABA application alone (100%) ± SD values, n = 3–8, significance value **p < 0.01.

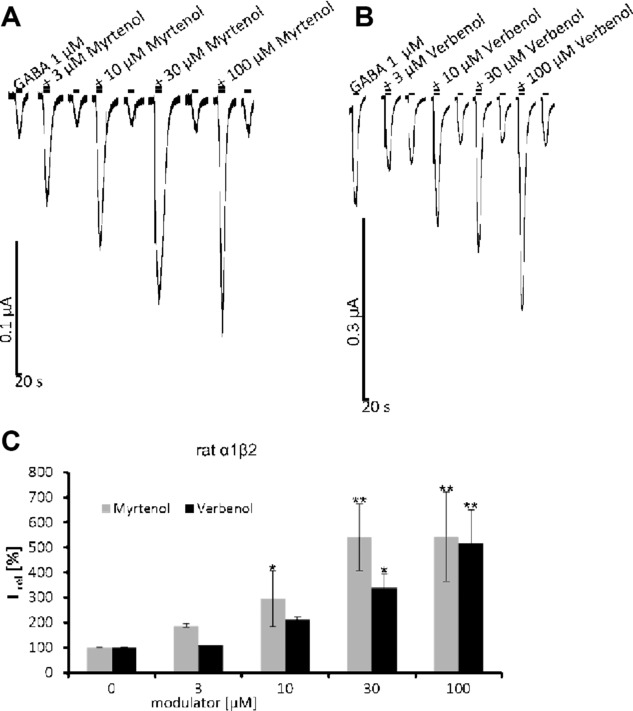

In addition to the 13 candidates resulting from a comparison of terpene structures, pinene metabolites were also investigated as pinenes were identified in all Sideritis extracts analyzed. Previous studies have shown that terpene substances may undergo major biotransformatory processes in vivo so that the active compounds might be represented by the formed derivatives 23. Interestingly, pinene metabolites verbenol and myrtenol at 100 μM were able to enhance GABA-evoked current responses up to 493 ± 82% (verbenol) and 541 ± 94% (myrtenol) of the current magnitudes of the pinene metabolite used compared to GABA application alone (Fig.3). Significant increases of the GABA-mediated currents were also observed at lower concentrations, e.g. 10 μM for myrtenol and 30 μM for verbenol (Fig.4A–C).

Figure 4.

Potentiating effect on GABAergic responses by metabolites of pinenes. Typical traces recorded from oocytes expressing rat α1β2 GABAARs and activated by GABA (1 μM) plus (A) myrtenol, and (B) verbenol at various concentrations (3 μM–100 μM). (C) Bar diagram representing the dose-dependent potentiation of GABA-mediated currents by verbenol (black bars) and myrtenol (gray bars). Data = mean ± SD, n = 3–9. The significance was tested compared to control (GABA alone), *p< 0.05; **p < 0.01.

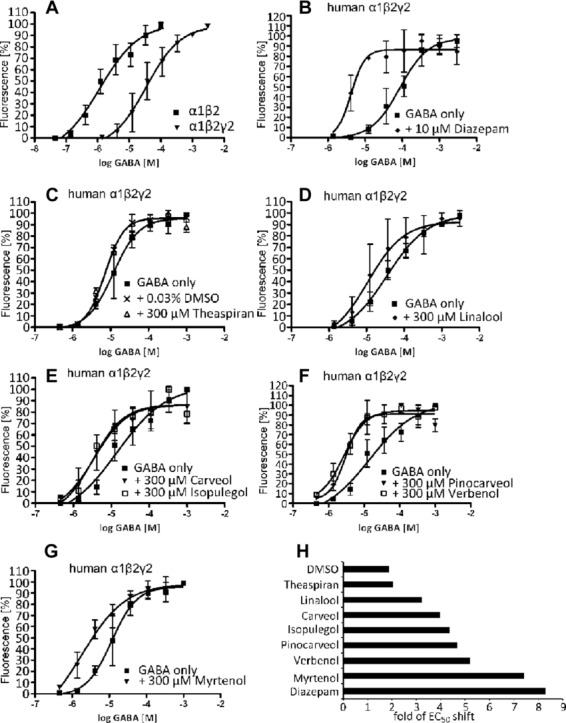

Potent substances were tested in a high-throughput assay using a Flexstation device. Here, transfected HEK293 cells expressing the α1β2γ2 configuration of the human GABAARs were used. GABA EC50s were 1.4 μM for α1β2 and 20.8 ± 7.0 μM for α1β2γ2 GABAARs, comparable to previously published data (e.g. Boileau et al.) (Fig.5A) 24. A coapplication of diazepam (10 μM) led to a 8.3-fold decrease in GABA EC50 (Fig.5B, Table3). Coapplication of terpenes (300 μM) myrtenol, verbenol, pinocarveol, and isopulegol together with increasing GABA concentrations caused a decrease in GABA EC50 (Fig.5). Myrtenol was identified as the volatile compound with the most pronounced effect on the GABA-dose–response curve (7.4 fold decrease in GABA EC50), not dissimilar to the effect of diazepam (Table3), while the decrease was ∼ fourfold for carveol and linalool (Fig.5D, E, and H).

Figure 5.

Flexstation data for the most potent modulators. (A) Concentration response curves for human α1β2 and human α1β2γ2 GABAARs results in a decrease in GABA EC50. (B–G) Dose–response curves with either GABA alone (used at concentrations 0.46 μM–1000 μM) or in the presence of different modulators (used at a fixed concentration of 300 μM). Data = mean ± SD, n = 3. (H) Bar diagram representing the shift in GABA-affinity (fold in EC50 shift).

Table 3.

Affinity changes of GABA EC50 values obtained from FLIPR experiments

| GABAAR subunits transfected | Agonist / modulator | pEC50 [M] | EC50 [μM] | Ratio [EC50 / EC50mod] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human α1β2γ2 | GABA | 4.75 ± 0.21 | 20.80 ± 7.00 | |

| Diazepam | 5.37 ± 0.06 | 4.19 ± 0.86 | 8.29 | |

| Linalool | 4.96 ± 0.38 | 10.80 ± 0.41 | 3.22 | |

| Carveol | 5.45 ± 0.22 | 3.59 ± 0.60 | 3.96 | |

| Isopulegol | 5.49 ± 0.16 | 3.26 ± 0.69 | 4.36 | |

| Pinocarveol | 5.52 ± 0.06 | 3.03 ± 0.87 | 4.68 | |

| Verbenol | 5.56 ± 0.12 | 2.73 ± 0.76 | 5.21 | |

| Theaspirane | 5.18 ± 0.08 | 6.56 ± 0.83 | 2.06 | |

| Myrtenol | 5.73 ± 0.33 | 1.83 ± 0.46 | 7.40 |

Mean values derived from Flexstation measurements (±SD). EC50 values from GABAARs expressed in HEK293 cells from three independent experiments.

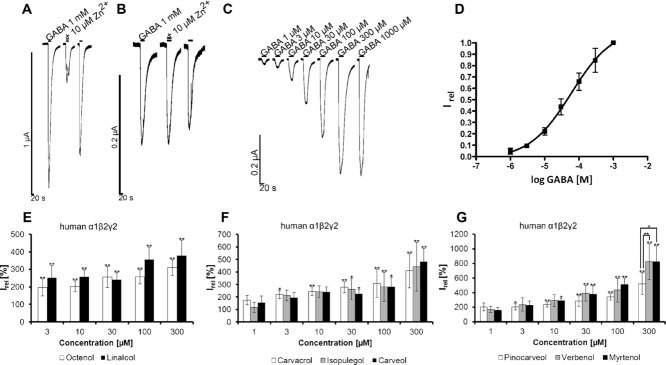

We also demonstrated that the effects of the terpenes and terpene-derived substances are similar in rat and human GABAAR subunits. Human α1β2γ2 GABAARs were expressed in oocytes and successful incorporation of the γ2 subunit demonstrated using Zn2+: no block was obtained, in contrast to Zn2+ inhibition for the α1β2 configuration (Fig.6A–D) 22. Linalool and 1-octen-3-ol (1000 μM) enhanced GABA-evoked currents of α1β2 GABAARs (Fig.2B). The coexpression of the γ2 subunit did not lead to significant changes in the effectiveness of GABA-current modulation by either linalool or 1-octen-3-ol (300 μM) (Fig.6E). These data indicate that the action of the volatile substances was independent of the γ2 subunit. The effectiveness of other substances and pinene metabolites on human GABAARs in an α1β2γ2 configuration was similar to the effects observed on rat α1β2 GABAARs in oocytes and Flexstation data using human α1β2γ2 in HEK293 cells. Modulation by pinocarveol, myrtenol, and verbenol achieved significance when used at concentrations >10 μM whereas for carvacrol, isopulegol, and carveol concentrations of at least 30 μM were required (Fig.6F and G). To determine the modulatory potency of these substances, however, concentration–response curves are required. The potentiating effect of structurally similar volatile substances is, therefore, independent from the origin of the GABAAR subunits. Thus, these substances most probably interact with conserved sequence motifs of the α1 and/or β2 GABAAR subunits.

Figure 6.

Modulatory effects of volatile terpenoid structures are independent of the origin of GABAARs subunits. (A) Typical traces of Zn2+-mediated inhibition of GABAergic currents on human α1β2 GABAARs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. (B) No Zn2+ inhibition was observed when human α1β2γ2 GABAA subunits are expressed. (C) Typical traces to application of various GABA concentrations measured from human α1β2γ2 GABAAR expressing oocytes (D) GABA dose–response curve of the human α1β2γ2 GABAAR expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Data = mean ± SD, n = 5; EC50 for GABA 59 ± 1.2 μM, the Hill coefficient nH was determined to 0.7. (E–G) Dose-dependent modulation of GABAergic currents by various terpenoids carvacrol, carveol, pinocarveol, isopulegol, myrtenol, and verbenol as well as linalool and 1-octen-3-ol as controls. *p < 0.5; **p < 0.01.

4 Discussion

Tea preparations from various Sideritis species are used as evening tea in Mediterranean countries. Previously, it was shown that mice with ad libitum access to Sideritis tea, improved in anxiolytic tests as well as showed enhanced antioxidative capacity in various brain structures. Various nonvolatile compounds were identified that may account for the observed effects 18. Moreover, it was shown that the volatile fraction of Sideritis extracts modulates α1β2 and α1β2γ2 GABAAR subtypes 3,18. Therefore, the action of the VOCs present in Sideritis extracts on GABAAR may be a distinct part of the underlying mechanism for a sedative action of such tea preparations in addition to effects of nonvolatile compounds. The volatile extracts potentiated GABAergic responses similar to Lavender extracts, where the main component linalool modulates GABAAR as well as other receptors such as voltage-dependent calcium channels 11,25–27. In the present study, single components identified within various Sideritis extracts have been analyzed for their ability to modulate different GABAAR subtypes. The extracts are rich in various terpenoids or terpene-derived structures including carvacrol and pinenes. Carvacrol was identified to significantly enhance α1β2 GABAARs with an effectiveness comparable to 1-octen-3-ol and linalool, which have been previously shown to modulate GABAARs 28. Earlier studies on α-pinene and its modulatory effect on GABAARs expressed in Xenopus oocytes have demonstrated an increase in the GABA-evoked currents at millimolar concentrations 29. Our results show that the single substances α-pinene, β-pinene, and β-caryophyllene led to a moderate enhancement of GABA-gated responses on GABAA α1β2 receptors similar to potentiation of the whole Sideritis extracts 3. Other substances such as sabinene, α-phellandrene, and caryophellene oxide had no influence on GABAergic currents. However, a combinatorial effect of substances in the extract was not investigated and can, therefore, not be excluded.

Pinenes and other monoterpenes are easily metabolized, e.g. by allylic oxidation in drosophila, rodents, and in humans. The effects of such secondary metabolites on the human central nervous system might be due to molecular and biochemical similarities 30,31. We observed that the substances, which harbored modulatory potential at GABAARs shared structural similarities such as their cyclic character (mono- or bicyclic), and the presence of a hydroxyl group. Accordingly, 13 similar terpenoid structures have been analyzed as individual candidates. Seven of these showed a strong modulatory effect on GABAARs of the α1β2 subtype. The same substances acted similarly on GABA-induced currents on α1β2γ2 GABAARs. A structural comparison revealed that almost all substances that lack modulatory potential did not contain a cyclic structure or they lacked a hydroxyl group. Recently, it was hypothesized that the adjacency of an isopropyl group to the hydroxyl group on a ring structure as present in propofol and menthol might share similar modulatory sites at GABAARs 32. Similar to the data obtained from Sideritis extracts, data on single substances indicate that the modulation is independent from the presence of the γ2 subunit 3. The γ2 subunit is important for the formation of the benzodiazepine-binding site between the α1 and the γ2 subunit. Benzodiazepines such as diazepam are anticonvulsant drugs used to treat patients suffering from various forms of epilepsy 33. Diazepam is, however, structurally dissimilar from terpene structures. Therefore, a modulatory action independent of the γ2 subunit, i.e. via a different binding interface than diazepam, is not surprising 34,35. The X-ray structure of a GABAAR homolog from prokaryotes ELIC provided evidence for two distinct binding sites for benzodiazepines an intrasubunit and an intersubunit binding site corresponding to a low-affinity and a high-affinity binding site of benzodiazepines 35. Thus, distinct modulatory binding sites for benzodiazepines and for VOCs may also exist on the GABAARs.

Hydrophobicity, however, is a common feature of both substance classes. A hydrophobic nature is a requirement for the VOCs and would enable them to reach their targets in the brain. Only a few reports are available that demonstrate and discuss the route of volatile odorants in vivo besides their binding to the olfactory receptors in the nasal epithelium 36–38. Odorant receptors are G-protein- coupled receptors that lead to an enhancement of cAMP in the cell, which triggers downstream signaling cascades 15,39.

These modulatory sites could have similar physiological consequences. Carvacrol, for example, was identified to harbor anxiolytic properties using an animal model of anxiety, the elevated plus maze test. In contrast, no effect on locomotor activity was observed for carvacrol. Mice pretreated with carvacrol displayed an increase in latency for the development of convulsions, however, only when used at high concentrations and less effective than (-)-borneol or citral 36,37. Nevertheless, the concentrations of volatile odorants that indeed are present at CNS neurons are still unknown and need further studies for clarification of this issue.

Alcohols and anesthetics also modulate GABAARs and other members of the Cys-loop receptor family 40,41. In vitro mutagenesis as well as X-ray crystallography of a bacterial homolog of the GABAARs GLIC, isolated from Gloeobacter violaceus, implied that the motion of residues in the transmembrane regions 2, 3, and 4 enable a transient communication between the inter- and intrasubunit cavities for propofol and other anesthetics 41,42. The crystallization of GLIC in the absence and presence of ethanol intriguingly illustrated residues localized in the transmembrane cavities involved in ethanol binding. F238, for example, participates in the binding of ethanol and similar modulators, thereby stabilizing the open-state conformation 41. Terpene structures that were able to modulate GABAARs are characterized by a cyclic structure and the presence of a hydroxyl group, which seem to be required for modulation. Isopulegol, verbenol, and myrtenol were identified to harbor the highest potential of modulation on α1β2 as well as α1β2γ2 GABAARs. Therefore, we postulate that they may have a similar mechanism to the action of various alcohols or anesthetics via an interaction at the GABAARs transmembrane domains. The enhancement of GABAergic currents mediated by VOC modulation at GABAARs might be explained by conformational changes following modulator interaction resulting in stabilization of the open channel.

In summary, we have identified some distinct volatiles, specifically terpenes, as modulators of the GABAARs providing an explanation of sedative effects. It was demonstrated by Löw et al. that in contrast to α1-containing receptors α2- and α3-containing receptors mediate anxiolytic effects 6. If terpenes act in a subunit-specific manner or act nonspecifically, it still needs further investigation. Recordings from GABAARs expressing neurons or brain slices might also prove useful to investigate the role of these substances in the target neuronal tissue. Thus, terpenes with distinct structural properties may mediate sedative or anxiolytic mechanisms involving GABAARs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Volker Eulenburg for advice in the TEVC analysis, Prof. C. Korbmacher from the Institute of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, University of Erlangen-Nuernberg, Erlangen, Germany, for providing the Xenopus oocytes, and Rosa Weber for excellent technical assistance. Dr. Kerry L. Price is gratefully acknowledged for help with Flexstation experiments. SCRL is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in basic biomedical science. The study is part of the Neurotrition Project, which is supported by the Emerging Field Initiative of the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuernberg. This project was supported by BMBF & Tubitak IntenC program and the Akdeniz University.

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Glossary

- DCM

Dichloromethane

- GABAARs

GABA receptors

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

5 References

- [1].Buchbauer G, Jirovetz L, Jager W, Plank C. Fragrance compounds and essential oils with sedative effects upon inhalation. J. Pharm. Sci. 1993;82:660–664. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600820623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hossain SJ, Aoshima H, Koda H, Kiso Y. Potentiation of the ionotropic GABA receptor response by whiskey fragrance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:6828–6834. doi: 10.1021/jf020448e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kessler A, Villmann C, Sahin-Nadeem H, Pischetsrieder M. GABAA receptor modulation by the volatile fractions of Sideritis species used as ‘Greek’ or ‘Turkish’ mountain tea. Flavour Frag. J. 2012;27:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gonzalez-Burgos E, Carretero ME, Gomez-Serranillos M P. Sideritis spp.: uses, chemical composition and pharmacological activities–a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:209–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Möhler H, Benke D, Rudolph U, Fritschy JM. GABAA receptors. In: Kew J, Davies C, editors. Ion Channels: From Structure to Function. Canada: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 263–276. in: (Eds.), [Google Scholar]

- [6].Low K, Crestani F, Keist R, Benke D. Molecular and neuronal substrate for the selective attenuation of anxiety. Science. 2000;290:131–134. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McKernan RM, Rosahl TW, Reynolds DS, Sur C. Sedative but not anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are mediated by the GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subtype. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:587–592. doi: 10.1038/75761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kloda JH, Czajkowski C. Agonist-, antagonist-, and benzodiazepine-induced structural changes in the alpha1 Met113-Leu132 region of the GABAA receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:483–493. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mihic SJ, Whiting PJ, Klein RL, Wafford KA. A single amino acid of the human gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor gamma 2 subunit determines benzodiazepine efficacy. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:32768–32773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hossain SJ, Hamamoto K, Aoshima H, Hara Y. Effects of tea components on the response of GABA(A) receptors expressed in Xenopus Oocytes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:3954–3960. doi: 10.1021/jf011607h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sergeeva OA, Kletke O, Kragler A, Poppek A. Fragrant dioxane derivatives identify beta1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:23985–23993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Buck LB. Receptor diversity and spatial patterning in the mammalian olfactory system. Ciba Found. Symp. 1993;179:51–64. doi: 10.1002/9780470514511.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Neuhaus W, Trauner G, Gruber D, Oelzant S. Transport of a GABAA receptor modulator and its derivatives from Valeriana officinalis L. s. l. across an in vitro cell culture model of the blood-brain barrier. Planta Med. 2008;74:1338–1344. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1081343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Menini A, Lagostena L, Boccaccio A. Olfaction: from odorant molecules to the olfactory cortex. News Physiol. Sci. 2004;19:101–104. doi: 10.1152/nips.1507.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dubey RK, McAllister CB, Inoue M, Wilkinson GR. Plasma binding and transport of diazepam across the blood-brain barrier. No evidence for in vivo enhanced dissociation. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;84:1155–1159. doi: 10.1172/JCI114279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Satou T, Matsuura M, Takahashi T, Umezu S. Anxiolytic-like effect of essential oil extracted from Abies sachalinensis. Flavour Frag. J. 2011;26:416–420. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vasilopoulou CG, Kontogianni VG, Linardaki ZI, Iatrou G. Phytochemical composition of “mountain tea” from Sideritis clandestina subsp. clandestina and evaluation of its behavioral and oxidant/antioxidant effects on adult mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013;52:107–116. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Engel W, Bahr W, Schieberle P. Solvent assisted flavour evaporation–a new and versatile technique for the careful and direct isolation of aroma compounds from complex food matrices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 1999;209:237–241. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bemelmans JMH. Review of isolation and concentration techniques. In: Land GG, Nursten HE, editors. Progress in Flavour Research. London: Applied Science Publisher; 1979. pp. 79–98. in: (Eds.), [Google Scholar]

- [21].Van den Dool H, Kratz PD. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas–liquid partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1963;11:463–471. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hosie AM, Dunne EL, Harvey RJ, Smart TG. Zinc-mediated inhibition of GABA(A) receptors: discrete binding sites underlie subtype specificity. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:362–369. doi: 10.1038/nn1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Heinlein A, Buettner A. Monitoring of biotransformation of hop aroma compounds in an in vitro digestion model. Food Funct. 2012;3:1059–1067. doi: 10.1039/c2fo30061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boileau AJ, Li T, Benkwitz C, Czajkowski C. Effects of gamma2S subunit incorporation on GABAA receptor macroscopic kinetics. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:1003–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Huang L, Abuhamdah S, Howes MJ, Dixon CL. Pharmacological profile of essential oils derived from Lavandula angustifolia and Melissa officinalis with anti-agitation properties: focus on ligand-gated channels. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2008;60:1515–1522. doi: 10.1211/jpp/60.11.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Narusuye K, Kawai F, Matsuzaki K, Miyachi E. Linalool suppresses voltage-gated currents in sensory neurons and cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Neural. Transm. 2005;112:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0187-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schuwald AM, Noldner M, Wilmes T, Klugbauer N. Lavender oil-potent anxiolytic properties via modulating voltage dependent calcium channels. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Johnston GA. GABA(A) receptor channel pharmacology. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005;11:1867–1885. doi: 10.2174/1381612054021024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Aoshima H, Hamamoto K. Potentiation of GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes by perfume and phytoncid. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999;63:743–748. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Adams TB, Gavin CL, McGowen MM, Waddell W J. The FEMA GRAS assessment of aliphatic and aromatic terpene hydrocarbons used as flavor ingredients. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49:2471–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hold KM, Sirisoma NS, Ikeda T, Narahashi T. Alpha-thujone (the active component of absinthe): gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor modulation and metabolic detoxification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2000;97:3826–3831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070042397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Watt EE, Betts BA, Kotey FO, Humbert DJ. Menthol shares general anesthetic activity and sites of action on the GABA(A) receptor with the intravenous agent, propofol. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;590:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, Corry MD. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:631–637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Krampfl K, Lepier A, Jahn K, Franke C. Molecular modulation of recombinant rat alpha1beta2gamma2 GABA(A) receptor channels by diazepam. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;256:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00767-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Spurny R, Ramerstorfer J, Price K, Brams M. Pentameric ligand-gated ion channel ELIC is activated by GABA and modulated by benzodiazepines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109:E3028–E3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208208109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Melo F H, Venancio ET, de Sousa DP, de Franca Fonteles MM. Anxiolytic-like effect of Carvacrol (5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol) in mice: involvement with GABAergic transmission. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010;24:437–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Quintans-Júnior LJ, Adriana G, Guimarães AG, Araújo BES. Carvacrol, (−)-borneol and citral reduce convulsantactivity in rodents. Afr. J. Biotech. 2010;9:6566–6572. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Raza M, Alghasham AA, Alorainy MS, El-Hadiyah TM. Potentiation of valproate-induced anticonvulsant response by nigella sativa seed constituents: the role of GABA receptors. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim) 2008;2:15–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Krautwurst D, Yau KW, Reed RR. Identification of ligands for olfactory receptors by functional expression of a receptor library. Cell. 1998;95:917–926. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Borghese CM, Blednov YA, Quan Y, Iyer SV. Characterization of two mutations, M287L and Q266I, in the alpha1 glycine receptor subunit that modify sensitivity to alcohols. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012;340:304–316. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sauguet L, Howard RJ, Malherbe L, Lee US, Corringer PJ. Structural basis for potentiation by alcohols and anaesthetics in a ligand-gated ion channel. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1697. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nury H, Van Renterghem C, Weng Y, Tran A. X-ray structures of general anaesthetics bound to a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2011;469:428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature09647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]