Abstract

Effective targeted therapy strategies are still lacking for the 15–20% of melanoma patients whose melanomas are driven by oncogenic NRAS. We here report on the NRAS-specific behavior of amuvatinib, a kinase inhibitor with activity against c-KIT, Axl, PDGFRα and Rad51. An analysis of BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines showed the NRAS-mutant cohort to be enriched for targets of amuvatinib, including Axl, c-KIT and the Axl ligand Gas6. Increasing concentrations of amuvatinib selectively inhibited the growth of NRAS- but not BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines, an effect associated with induction of S- and G2/M-phase cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis. Mechanistically, amuvatinib was noted to either inhibit Axl, AKT and MAPK signaling or Axl and AKT signaling and to induce a DNA damage response. In 3D cell culture experiments, amuvatinib was cytotoxic against NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines. Thus we show for the first time that amuvatinib has pro-apoptotic activity against melanoma cell lines, with selectivity observed for those harboring oncogenic NRAS.

Keywords: melanoma, BRAF, NRAS, amuvatinib, MP470, RTK

Introduction

Genetic profiling has provided new avenues for targeted therapy, offering a paradigm whereby kinase inhibitors with defined activity profiles can be matched to tumors with specific driver mutations. This approach has been successfully used in the clinic, with impressive responses being seen when BRAF-mutant melanomas are treated with BRAF inhibitors and the BRAF/MEK inhibitor combination (1). Despite this, no good targeted therapy strategies yet exist for the 15–20% of all cutaneous melanomas that are driven through activating mutations in the small GTPase NRAS. Melanomas with NRAS mutations exhibit different biological behavior to their BRAF-mutant counterparts and signal through CRAF, rather than BRAF (2, 3). In addition, they exhibit constitutive signaling through the PI3K/AKT and Ral-GDS pathways and typically lack inactivation/mutation in the tumor suppressor PTEN (4, 5). The only strategy with proven efficacy in this melanoma sub-group has been small molecule inhibitors of MEK. In a phase II clinical trial, the MEK inhibitor MEK-162 was associated with response rates of 20%, and a progression free survival of 3.6 months (6). Although MEK inhibitor monotherapy is being investigated in a phase III clinical trial, experience with BRAF inhibitors suggests that combination strategies may give more durable responses.

Melanoma cell lines and tumor specimens express a large number of cell surface receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), all with the potential to drive cell growth and survival (7, 8). There is some preclinical evidence that multi-targeted kinase inhibitors, such as RAF-265, may have in vivo activity against patient-derived BRAF wild-type melanoma xenografts, including those with NRAS Q61R mutations (9). Here we present the first preclinical data showing the potential efficacy of the RTK inhibitor amuvatinib against NRAS-mutant melanoma.

Materials and methods

Cell Culture and Reagents

The 1205Lu, WM9, WM793, WM164, WM983A, and WM35 BRAF-mutant as well as the WM1346, WM1366, WM1361A, Sbcl-2, WM852 NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines were a generous gift from Dr. Meenhard Herlyn (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA). The identities of all cell lines were confirmed by Biosynthesis Inc (Lewisville, Tx) through STR validation analysis. All cell lines were grown in 5% FBS/RPMI-1640. Amuvatinib was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX).

Phosphoproteomics sample preparation, LC-MS/MS and analysis

Cells were lysed in denaturing buffer then proteins were reduced, alkylated and digested with trypsin. The tryptic peptides were then desalted and lyophilized, with enrichment for phosphotyrosine-containing peptides using immunoprecipitation with immobilized anti-phosphotyrosine antibody p-Tyr-100 (Cell Signaling Technology). A nanoflow ultra high performance liquid chromatograph (RSLC, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) coupled to an electrospray ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap, Thermo, San Jose, CA) was used for tandem mass spectrometry. After Sequest and Mascot searches, the results were summarized in Scaffold 3.0. The relative quantification of tyrosine-phosphorylated peptides was calculated using MaxQuant (ver 1.2.2.5). Multi Experiment Viewer was used for generating a heatmap of the relative pY intensities (version 4.8.1) and performing Pearson correlation analysis between NRAS- and BRAF-mutant cell line cohorts.

Western Blot

Proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (0.5M Tris, Triton X-100, Na-deoxycholate, 10% SDS, NaCl, 0.5M EDTA) containing Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Protein extracts were resolved on Novex 8–16% Tris-glycine gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and immunoblotted using antibodies to pAKT, AKT, pERK, ERK, pAXL, AXL, MET, c-KIT, Rad51, GSK3β from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Uniform protein loading was confirmed by blotting for GAPDH.

Growth Inhibition Assay

Cells were plated in a 96-well plate (2.5x103 per well) and left to attach overnight before being treated with vehicle or increasing doses of amuvatinib for 72 hours. Cells were then incubated with MTT reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for three hours, and the crystals solubilized in DMSO followed by a measurement of absorbance at 570 nm.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells were plated at 60% confluency and allowed to attach overnight in 10cm plates. They were then treated with vehicle or amuvatinib for 72 hours, stained with Propidium Iodide (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and analyzed by flow cytometry. ModFit software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME) was used for DNA analysis and modeling.

Apoptosis Analysis

Cells were allowed to attach in 6-well plates overnight, then treated with vehicle or increasing doses of amuvatinib for 72 hours. Cells were then stained with APC-conjugated Annexin V (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 25 nmol/L tetramethylrhodamine, methyl ester, perchlorate (TMRM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Staining of cells was then analyzed using flow cytometry. Gates were delineated based on regions of distinct populations.

3D Spheroid Culture

Melanoma spheroid cultures were established using the method previously described (10). Spheroids were treated with vehicle or increasing doses of amuvatinib for 7 days, then stained with calcein-AM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and propidium Iodide.

Colony Formation Assay

Cells were incubated in six-well plates (1 × 104 per well) overnight, before being treated with vehicle or increasing doses of amuvatinib. Cells were left to grow for 2 weeks with new drug added twice per week. Wells were stained with crystal violet solution (50% methanol + 50% H2O + 0.5% crystal violet).

Immunofluorescent Staining

Cells were plated on glass coverslips in six-well plates and incubated overnight. Cells were then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 prior to blocking in 1% BSA/PBS. Coverslips were incubated with AlexaFluor 555-conjugated phospho-H2AX antibody overnight at 4°C. Coverslips were washed and mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies, Carlsband, CA).

Microarray

Microarray data and its analysis was previously outlined (11).

Statistical Analysis and IC50 calculations

Results are reported as mean values, error bars indicating ± SEM were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 software. GraphPad Prism was also used to calculate the IC50 values for the growth inhibition assay.

Results and discussion

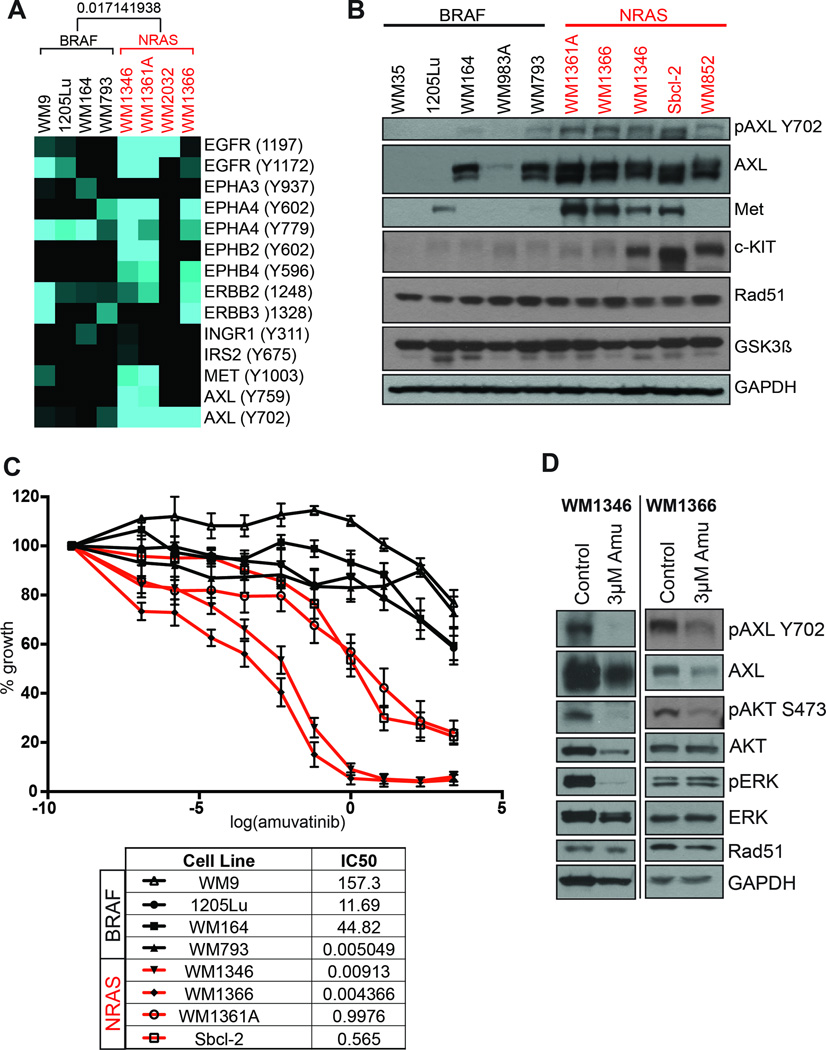

Baseline RTK signaling was investigated in a panel of BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines using a comprehensive phosphoproteomic approach in which tyrosine phosphorylated peptides were immunoprecipitated followed by tandem mass spectrometry (Work flow shown in Supplemental Figure 1A). It was noted that NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines had constitutive phosphorylation of Axl, ERBB2, c-MET, EGFR and Ephrins (Figure 1A). In all cases, patterns of RTK signaling were heterogeneous and cell line specific. Melanoma cell lines with BRAF V600E mutations showed relatively little basal RTK signaling, with the exceptions of ephrin A4 and one cell line (WM9) with EGFR/ERBB2/ERBB3 activity (Figure 1A). The analysis detailed here differs significantly from previous studies of RTK activity in melanoma cell lines in utilizing mass spectrometry to give precise, quantitative readouts on specific phosphorylation sites (Figure 1A) (7, 8). In agreement with previously published studies, we noted basal tyrosine phosphorylation of Axl at Y702 in all of the NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines that was lacking in those that were BRAF-mutant (12). A number of studies have implicated TAM family RTKs in melanoma, with work showing that Axl is activated through an autocrine Axl/Gas6 signaling loop to enhance levels of cell invasion (12).

Figure 1. NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines express targets of amuvatinib and are growth inhibited following amuvatinib treatment.

A: Summary of phosphoproteomic data from the mass spectrometry based pY analysis. Hierarchical clustering using the Pearson correlation lead to a clear separation of BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines, Pearson correlation between BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines shown on heatmap (deeper clustering not shown). B: Western blot showing expression of amuvatinib targets in BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines. C: Amuvatinib has growth inhibitory effects in NRAS but not BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines. Melanoma cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of amuvatinib for 72 hrs before being analyzed by the MTT assay. D: Amuvatinib (3 µM, 72 hrs), leads to decreased pAXL, pAKT and pERK expression by Western blot.

Amuvatinib is an orally available tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against mutant Kit, c-MET, platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-α and Rad51 (13, 14). Western blot and microarray analysis showed NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines to express multiple amuvatinib targets including Axl, c-MET, and c-KIT that were generally lacking in BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines (Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 1B). The expression of other amuvatinib targets such as Rad51 and GSK3β was uniform across both BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines (Figure 1B). In agreement with NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines expressing multiple amuvatinib targets, the drug was noted to have significant anti-proliferative activity in NRAS- but not BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines (Figure 1C). From a mechanistic standpoint amuvatinib inhibited the phosphorylation of Axl and AKT in the WM1366 and WM1364 NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines (Figure 1D). In the WM1346 cell line, amuvatinib also inhibited ERK phosphorylation (Figure 1D). These observations agree with other studies showing the dual targeting of MEK and PI3K/AKT to have good efficacy in NRAS-mutant melanoma (15). Although only modest reductions were seen in Rad51 expression in both WM1366 and WM1346 cells, there was evidence of a DNA damage response being induced, as shown by increased γ-H2AX staining (Supplemental Figure 2). Previous work has demonstrated amuvatinib to reduce Rad51-mediated homologous DNA repair, leading to enhanced radiation sensitivity (16).

Analysis of cell cycle distributions showed amuvatinib to have little effect upon the accumulation of cells in G1, with increases in the percentage of cells in S- and G2/M seen (Figure 2A). As amuvatinib had relatively minor effects upon the cell cycle, we next determined the role of apoptosis induction in the observed cytotoxic effects of the drug. It was noted that amuvatinib treatment was associated with a concentration-dependent induction of apoptosis, as demonstrated by rounding up and detachment of cells from the culture vessel, increased annexin-V binding and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 3A). Under 3D cell culture conditions, amuvatinib exhibited significant cytotoxic activity upon both WM1346 and WM1366 melanoma cell lines as demonstrated by the loss of cell viability (reduced calcein-AM staining) and increased cell death (increased propidium iodide staining) (Figure 2C). The growth inhibition seen to amuvatinib was prolonged, with a long-term suppression of growth observed in 14-day colony formation assays of NRAS-mutant but not BRAF-mutant melanoma cells (Figure 2D and Supplemental Figure 3B). The effects observed were more pronounced and durable than those seen to MEK inhibitors, such as selumetinib and trametinib, where regrowth of colonies was always seen Rebecca et al., Submitted).

Figure 2. Amuvatinib has long-term cytotoxic, growth suppressive effects in NRAS-mutant melanoma cell lines.

A: Cell cycle effects of amuvatinib upon WM1366 NRAS-mutant melanoma cells. 72 hr treatment with amuvatinib leads to a decrease in G1-phase cells and an increase in G2/M and S-phase. B: Amuvatinib induces apoptosis in NRAS-mutant but not BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines. Cells were treated with amuvatinib (3 µM, 72 hrs) before being analyzed for Annexin-V binding/loss of TMRM by flow cytometry. C: Amuvatinib is cytotoxic in a 3D collagen implanted spheroid model of NRAS-mutant melanoma. Spheroids from WM1366 and WM1346 melanoma cells were treated with amuvatinib for 7 days before being stained with calcein-AM (green, live cells) and propidium iodide (red, dead cells). D: Amuvatinib leads to long-term growth suppression of NRAS-mutant melanoma cells. Data shows colony formation assays performed over 14 days.

The ability of oncogenic Ras to activate multiple signaling pathways including MAPK, PI3K/AKT, Ral-GDS and other small G-proteins has made the development of targeted therapies a challenge (2). Although attempts are ongoing to develop rational combinations such as PI3K/MEK and MEK/CDK4 inhibitors, these are often associated with toxicity and may not show efficacy in every patient (15, 17). Kinase inhibitors that target multiple-RTKs may be effective in NRAS-mutant melanoma. It is likely that RTK inhibitors are less effective in BRAF-mutant melanomas because of high levels of feedback inhibition in the MAPK pathway that limits signals through Ras (18). There is already evidence that RAF-265 has good anti-tumor activity in a subset of BRAF wild-type melanoma patient-derived xenografts (9). NRAS-mutant melanoma patients also showed better clinical responses to the combination of sorafenib with carboplatin + paclitaxel than their BRAF-mutant counterparts (19). Our data adds to this and suggest that amuvatinib may be of utility in some NRAS-mutant melanomas, particularly those that are dependent upon the targets of this drug. The emerging evidence suggests that NRAS-mutant melanomas are more diverse than BRAF-mutant melanoma, potentially requiring the development of highly personalized therapeutic strategies on a patient-by-patient basis (20). Enhanced genetic profiling integrated with quantitative proteomic profiling is likely to play a key role in future therapy selection that allows durable responses to be achieved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Work in the Smalley lab is supported by SPORE grant 1P50CA168536-01A1 and R01 CA161107-01 from the National Institutes of Health. Inna Fedorenko was supported by a grant from the Joanna M. Nicolay Melanoma Foundation. The Moffitt Proteomics Facility is supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (W81XWH-08-2-0101) for a National Functional Genomics Center, the National Cancer Institute (P30-CA076292) as a Cancer Center Support Grant, and the Moffitt Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedorenko IV, Gibney GT, Smalley KS. NRAS mutant melanoma: biological behavior and future strategies for therapeutic management. Oncogene. 2013;32:3009–3018. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marquette A, Andre J, Bagot M, Bensussan A, Dumaz N. ERK and PDE4 cooperate to induce RAF isoform switching in melanoma. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:584–591. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao H, Goel V, Wu H, Yang G, Haluska FG. Genetic interaction between NRAS and BRAF mutations and PTEN/MMAC1 inactivation in melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:337–341. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.22243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra PJ, Ha L, Rieker J, Sviderskaya EV, Bennett DC, Oberst MD, et al. Dissection of RAS downstream pathways in melanomagenesis: a role for Ral in transformation. Oncogene. 2010;29:2449–2456. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascierto PA, Schadendorf D, Berking C, Agarwala SS, van Herpen CM, Queirolo P, et al. MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. The lancet oncology. 2013;14:249–256. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molhoek KR, Shada AL, Smolkin M, Chowbina S, Papin J, Brautigan DL, et al. Comprehensive analysis of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in human melanomas reveals autocrine signaling through IGF-1R. Melanoma Research. 2011;21:274–284. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328343a1d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tworkoski KA, Platt JT, Bacchiocchi A, Bosenberg M, Boggon TJ, Stern DF. MERTK controls melanoma cell migration and survival and differentially regulates cell behavior relative to AXL. Pigm Cell Melanoma R. 2013;26:527–541. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Y, Vilgelm AE, Kelley MC, Hawkins OE, Liu Y, Boyd KL, et al. RAF265 inhibits the growth of advanced human melanoma tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:2184–2198. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smalley KS, Haass NK, Brafford PA, Lioni M, Flaherty KT, Herlyn M. Multiple signaling pathways must be targeted to overcome drug resistance in cell lines derived from melanoma metastases. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1136–1144. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tafreshi NK, Silva A, Estrella VC, McCardle TW, Chen T, Jeune-Smith Y, et al. In vivo and in silico pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of a melanocortin receptor 1 targeted agent in preclinical models of melanoma. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2013;10:3175–3185. doi: 10.1021/mp400222j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sensi M, Catani M, Castellano G, Nicolini G, Alciato F, Tragni G, et al. Human Cutaneous Melanomas Lacking MITF and Melanocyte Differentiation Antigens Express a Functional Axl Receptor Kinase. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2011;131:2448–2457. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi W, Cooke LS, Stejskal A, Riley C, Croce KD, Saldanha JW, et al. MP470, a novel receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in combination with Erlotinib inhibits the HER family/PI3K/Akt pathway and tumor growth in prostate cancer. Bmc Cancer. 2009;9:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillip CJ, Zaman S, Shentu S, Balakrishnan K, Zhang J, Baladandayuthapani V, et al. Targeting MET kinase with the small-molecule inhibitor amuvatinib induces cytotoxicity in primary myeloma cells and cell lines. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posch C, Moslehi H, Feeney L, Green GA, Ebaee A, Feichtenschlager V, et al. Combined targeting of MEK and PI3K/mTOR effector pathways is necessary to effectively inhibit NRAS mutant melanoma in vitro and in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:4015–4020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216013110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao H, Luoto KR, Meng AX, Bristow RG. The receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor amuvatinib (MP470) sensitizes tumor cells to radio- and chemo-therapies in part by inhibiting homologous recombination. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2011;101:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwong LN, Costello JC, Liu H, Jiang S, Helms TL, Langsdorf AE, et al. Oncogenic NRAS signaling differentially regulates survival and proliferation in melanoma. Nature Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nm.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lito P, Pratilas CA, Joseph EW, Tadi M, Halilovic E, Zubrowski M, et al. Relief of Profound Feedback Inhibition of Mitogenic Signaling by RAF Inhibitors Attenuates Their Activity in BRAFV600E Melanomas. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:668–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson MA, Zhao F, Letrero R, D'Andrea K, Rimm DL, Kirkwood JM, et al. Correlation of somatic mutations and clinical outcome in melanoma patients treated with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and sorafenib. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rebecca VW, Wood ER, Fedorenko IV, Paraiso KH, Haarberg HE, Chen Y, et al. Evaluating Melanoma Drug Response and Therapeutic Escape with Quantitative Proteomics. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2014 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.037424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.