Abstract

Introduction:

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurobehavioral developmental disorder usually diagnosed in children, with appearance of the first symptoms before the age of seven years. The disorder is characterized by inattention and/or impulsivity and hyperactivity that can seriously affect many aspects of behavior and performance at school. ADHD can be associated with comorbidities, such as oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, anxiety or depression.

Material and Methods:

The study was done on a sample of 500 university students. For the measurement of ADHD symptoms, the ADHD Adult Self-report Scale was used and for depression measurement DASS.

Results:

The results of this screening study showed that ADHD is highly significant associated with gender (p = 0.0004). Men more often than women have this kind of disorder. Female students have attention subtype deficit, while man student have often hyperactivity/impulsivity disorder and combined subtype due to psychological, temperament and character gender differences among boys and girls. Female examinees are significantly (p=0.028) more often depressed compared to male examinees.

Conclusion:

The examined correlations are positive ones or direct, meaning that by increasing the values of the scores from both subscales from the Evaluation ADHD Scale one also increases the scores from the Depression Scale, and vice versa. For a value of p=0.001 and p=0.004 these correlations are statistically highly significant, in other words highly important.

Keywords: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, depression, correlation, gender, prevalence, subtypes, university students

1. INTRODUCTION

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is neurobehavioral developmental disorder (1, 2) mostly diagnosed in children, with appearance of the first symptoms before the age of seven years (3, 4). It is diagnosed twice more often in boys than in girls (5). The most common symptoms of ADHD are impulsivity (6), hyperactivity (6) and inattention (7). ADHD can seriously affect many aspects of behavior in school and at home. The prevalence of ADHD was until recently 3-5%, and over the past few years it has reached 8-12% worldwide, depending on the geographic and local factors. The varying prevalence rates also result from different definitions of the condition, questionnaires (parent or teacher as informant, or both) and interview techniques applied, and age and size of study sample. Using only the parent’s rating sales and assessments, the prevalence is 4-9% (8-19). ADHD may significantly affect an individual through childhood as well as in adulthood, especially if it is not optimally managed. ADHD has been associated with lower professional status, crime, and substance abuse (20). Both parents of a child with ADHD and community suffer the consequences of problems associated with ADHD (21,22). A number of people have symptoms of ADHD to an extent that it does not significantly affect their academic, professional and social performance. ADHD can be associated with comorbidities, such as oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, anxiety or depression (23, 24).

The aim of our research was to determine the prevalence and gender distribution of ADHD as well as to determine the subtypes and conditions (in this case depression) associated with it.

Classification

According to ICD -10, this disorder is categorized under the code F 90. According to this classification, following forms are present: F 90.0–Disorder in the activity and attention, F 90.1–Hyperkinetic behavior disorder, F 90.8–Other hyperkinetic disorders and 90.9–Unspecified hyperkinetic disorder (13). In this classification, there is no satisfactory division related to the symptoms of the disorder. It should be borne in mind that with the attention disorder and hyperactivity, there is aggressiveness, impulsivity, delinquency or anti-social behavior (14). The existing classification has no clear distinction of clinical images by which you can classify this disorder. According to DSM-IV symptoms, ADHD has three subtypes of the disease: 1. inattention 2. hyperactivity/impulsivity and 3. combined subtype.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study design was cross sectional. There were 127 boys and 251 girls. The target group consists of university students from the Faculty of Medical Sciences in Štip, a town in Macedonia. The number of participants in the survey is 500 respondents (in order to make better screening), from all years of study and from all four study programs (general medicine, dentistry, pharmacy and vocational studies). It represents 25% of the total number of students of medical sciences and every fourth student who attends the lectures will be included in the research.

Inclusion criteria: research concerns the students of the Faculty of Medical Sciences who agree to participate in research. Exclusion criteria: the research will not participate students who refuse to participate because of personal reasons.

Instruments

In our country, there is still no standardized scale, so for determining the symptomatology of ADHD we decided to use the Adult Self-report Scale as a measuring instrument. It gives a solid display of symptoms associated with behavior and global impression.

DAS (Depression, anxiety, stress) scale represents a questionnaire with 42 questions (items) and it includes 3 self-evaluation subscales which measure negative emotional states such as: depression, anxiety and stress.

3. RESULTS

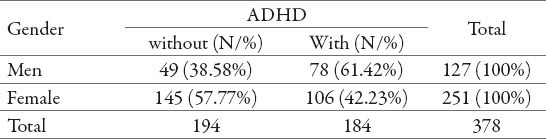

The research results show that the ADHD is highly significant associated with gender (p = 0.0004). Men more often than women have this kind of disorder. Gender distribution is shown in Table 1 and Figure 2 where is noted that activity disorder and attention is revealed in 61.4% of male respondents and in 42.2% of female respondents (Table 1)

Table 1.

ADHD-gender distribution. Pearson Chi-square: 1.43, df=1, p=0.0004** p<0.01

Figure 2.

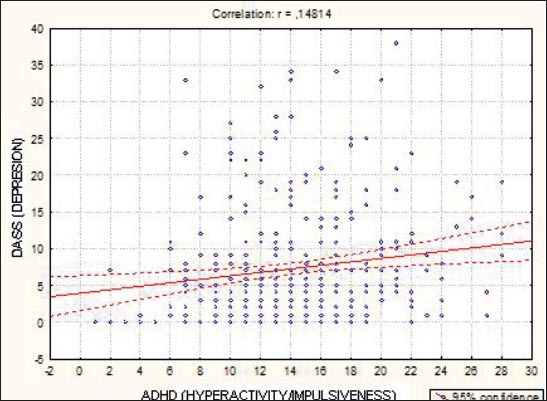

Correlation-Depression / ADHD(hyperactivity/impulsiveness). r = 0.148 p=0.004 p<0.01

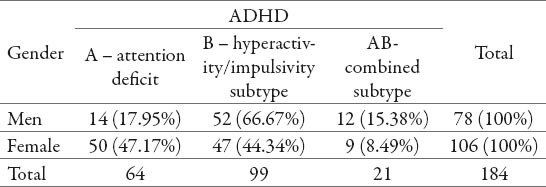

In the group of male respondents, dominates subtype B or hyperactive / impulsive type and is been identified in 66.7% of respondents, while among the female students is often present attention deficit disorder, observed in 47.2% female students. Male respondents is more likely to have combined subtype than females (subtype AB) (15.4% vs. 8.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

ADHD-Gender distribution of subtypes. Pearson Chi-square: 17.06, df=2, p=0.0002** p <0.01

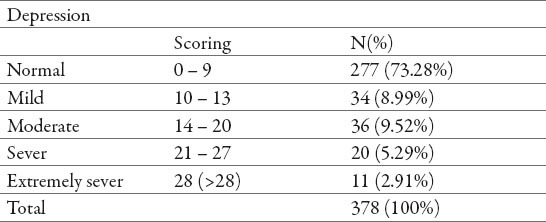

Table 3 shows the distribution of examinees in relation to the Depression Scale scores. The results show that 277 (73.3%) examinees have a score of 0 to 9, in other words no depression can be recognized in these students. Most of the examinees suffering from depression suffer from medium depression and they are represented with highest percentage–36(9.5%), in other words they have a score of 14 to 20. In the distribution shown it can be noticed that 11(2.9%) examinees have a score that is higher than 28 on the depression scale, being equivalent to existence of a much severe depression.

Table 3.

Depression Scale

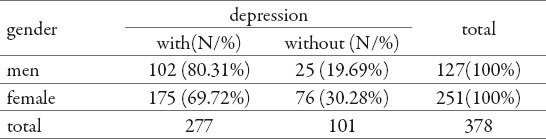

Female examinees are significantly (p=0.028) more often depressed compared to male examinees. The existence of depression can be recognized in 76 (30.3%) persons from the group of female students compared to 25 (29.7%) male students who suffer from depression according to the scale results.(Table 4)

Table 4.

Depression – gender distribution. Pearson Chi-square: 4.83, df=1, p=0.028* p<0.05

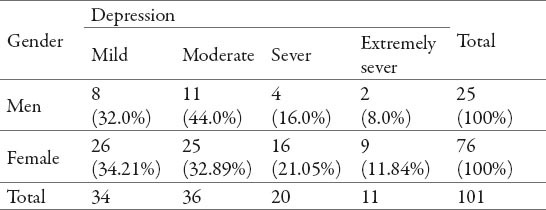

The severity of depression does not depend significantly (p=0.76) on the examinees’ gender. Female examinees suffer more often from severe depression (21.05% against 16%) and very severe depression (11.8% against 8%) compared to male examinees, whereas a medium level depression is more often found in male examinees (44% against 32.9%). However, these differences are statistically insufficient so that they can be confirmed as significant or important ones.(Table 5)

Table 5.

Depression Level–gender distribution. Pearson Chi-square: 1.18, df=3, p=0.76 p>0.05

Correlations

Figure 1 and 2 show the examined correlation between the Depression Scale as a dependent variable and the two subtypes of the Evaluation ADHD Scale (subtype A, in other words attention deficit, and subtype B, in other words hyperactivity/impulsiveness).

Figure 1.

Correlation-Depression / ADHD (attention deficit). r = 0.173 p=0.001 p<0.01

The Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient value is r=0.173 for the examined connection between depression and attention deficit, and r=0.148 for the examined connection between depression and hyperactivity/impulsiveness. These values show that the examined correlations are positive ones or direct, meaning that by increasing the values of the scores from both subscales from the Evaluation ADHD Scale one also increases the scores from the Depression Scale, and vice versa. For a value of p=0.001 and p=0.004 these correlations are statistically highly significant, in other words highly important.

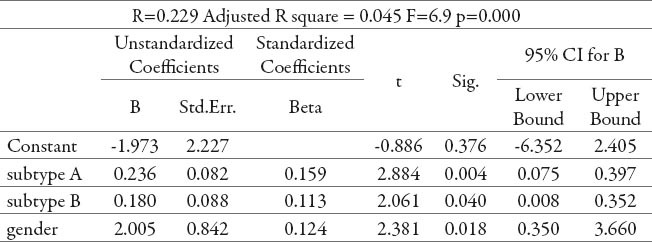

Table 6 displays the results from the Multiple Regression Analysis for determining the relationship of the three predictor variables (The Attention Deficit Scale, the Hyperactivity/Impulsiveness Scale and the Students Gender Scale) with the Depression Scale.

Table 6.

Multiple Regression. Dependent variable:depression

The value of R square =0.045 implicates that only 4.5% of changes in the depression scores can be explained with these three variables.

The Attention Deficit represents a highly significant (p=0.004) independent depression risk factor, whereas the hyperactivity/impulsiveness represents an independent-significant risk factor (p=0.04).

The value of coefficient B shows that any rise in the Attention Deficit Recognition Scale by one score results into an average rise in the Depression Scale by up to 0.236 (95% CI 0.075 to 0.397) and any rise in the Hyperactivity/Impulsiveness Recognition Scale by one score results into an average rise in the Depression Scale by up to 0.18 (95% CI 0.008 to 0.352).

The examinees’ gender is included in this model as a predictor variable and here the B coefficient value shows that female students have an average of 2 (95% CI 0.35 to 3.66) significantly higher scores on the Depression Scale compared to male students. From all three independent predictor variables analyzed the Beta coefficient value shows that the attention deficit (Beta = 0.159) has a highest impact on depression.

4. DISCUSSION

The research has proved that the prevalence rate of ADHD with respect to student population and gender distribution is higher in the male population, and here the “hyperactivity/impulsiveness” subtype is prevalent in the male population, whereas the “inattention” subtype is predominant in the female population. All this is due to the way of expressing symptomatology depending on gender. As a result of the more stressed emotional component within the nature of their personality female subjects are inclined to react “introvertedly”, whereas male subjects are inclined to react “extrovertedly” and manifest the symptomatology, thus presenting the relevant disorders and psychic states.

Accordingly, anxiety and depression are prevalent in the female population.

There are several theories aimed at explaining the higher incidence of anxiety disorders or depression in persons suffering from ADHD. One theory assumes that as a result of the same neuro-biologic systems controlling attention and mood it is reasonable for one to assume that ADHD neurological causes are also a cause of anxiety disorders or depression. Another theory assumes that anxiety disorders and depression are a result of living with ADHD, especially if the difficulties to maintain attention remain undiagnosed or untreated for a very long period, which also leads to a chronic sensation of failure, frustration, disappointment, defeat. Making a correct diagnosis that takes ADHD and anxiety or depression into mind is not always a simple task. Frequently, ADHD can be diagnosed, whereas the anxiety disorder or depression can be neglected although they exist.

Many young people and students with ADHD symptomatology also have symptoms of depression. The feeling of chronic bad mood is frequent therein. The suicide rate also grows. Anxiety and insomnia accompanying depression also contribute to emphasizing the problems connected with inattention.

Studies suggest that students who suffer from depression, especially female individuals, have behaviors that are connected with alcohol and psychoactive substance abuse, as well as promiscuous behavior.

5. CONCLUSION

Availability of ADHD medications has a significant role in the treatment and reducing symptoms of this condition. In Macedonia, no medications for ADHD have been registered yet and people with this condition have to buy them abroad.

Physicians, teachers, parents and other people working with children should be educated about the ADHD symptoms in order to recognize them early and enable appropriate and timely treatment. Encouragement of medication use, education on time structuring and behavioral control, social skill training, and frequent cognitive redirecting is needed.

Studies on the prevalence of ADHD in relation to comorbid disorders are scarce, and these aspects should be researched more thoroughly.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: Is it an American condition? World Psychiatry. 2003;2:104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwi M, Ramchandani P, Joughin C. Evidence and belief in ADHD. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2000;321 (7267):975–976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7267.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhill LL. Diagnosing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 7):31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair J, Ehimare U, Beitman BD, Nair SS, Lavin A. Clinical review: evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in children. Mo Med. 2006;103(6):617–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dulcan M. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(10 Suppl):85S–121S. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). National Institute of Mental Health. 2009 May 08; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paule MG, Rowland AS, Ferguson SA, et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: characteristics, interventions and models. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22(5):631–651. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor E, Sandberg S. Hyperactive behavior in English schoolchildren: a questionnaire survey. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984 doi: 10.1007/BF00913466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor A. London: The Spastics Society; 1986. The overactive child. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleeson D, Parker D. Hyperactivity in a group of children referred to a Scottish Child Guidance Service: a significant problem. Br J Educ Psychol. 1989;59:262–265. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1989.tb03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller RG, Palkes HS, Stewart MA. Hyperactive children in suburban elementary schools. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1973;4:121–127. doi: 10.1007/BF01433256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert NM, Sandoval J, Sassone D. Prevalence of hyperactivity in elementary school children as a function of social system definers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1978;48:446–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1978.tb01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safer D, Allen RP. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1976. Hyperactive children: diagnosis and management. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadow KD, Nolan EE, Litcher L, et al. Comparison of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom subtypes in Ukrainian school children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1520–1527. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgaertel A, Wolraich ML, Dietrich M. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for attention deficit disorders in a German elementary school sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:629–638. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolraich ML, Hannah JN, Pinnock TY, et al. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in a county-wide sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:319–324. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolraich ML, Hannah JN, Baumgaertel A, et al. Examination of DSM-IV criteria for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a county-wide sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:162–168. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graetz BW, Sawyer MG, Hazell PL, et al. Validity of DSMIV ADHD subtypes in a nationally representative sample of Australian children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1410–1417. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson JM, Sergeant JA, Taylor E, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperkinetic disorder. Lancet. 1998;351:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:21–29. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mash EJ, Johnston C. Parental perceptions of child behavior problems, parenting self-esteem, and mothers’ reported stress in younger and older hyperactive and normal children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:86–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy KR, Barkley RA. Parents of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: psychological and attentional impairment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:93–102. doi: 10.1037/h0080159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauermeister J, Shrout P, Chávez L, Rubio-Stipec M, Ramírez R, Padilla L, et al. ADHD and gender: are risks and sequela of ADHD the same for boys and girls? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2007;48(8):831–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudjonsson GH, et al. The relationship between satisfaction with life, ADHD symptoms and associated problem among university students. Journal od Attention Disorders. 2009;12:507–515. doi: 10.1177/1087054708323018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]