Introduction

The antigens of the ABO blood group system (A, B and H determinants, respectively) are complex carbohydrate molecules on the extracellular surface of red blood cells1. However, besides being expressed on red blood cells, ABO antigens are also strongly expressed on the surface of a variety of human cells and tissues, including the epithelium, sensory neurones, platelets, and the vascular endothelium2. The clinical significance of the ABO blood group system does, therefore, extend beyond transfusion medicine as several reports have suggested an important involvement in the development of cardiovascular, oncological and other diseases3,4. In particular, a number of clinical studies and systematic reviews have documented a positive association between non-O blood type and the risk of developing both venous and arterial thrombotic events5–8. Although the underlying molecular mechanisms are not completely understood, ABO-related thrombosis is thought to be mediated by ABO carbohydrate modifications of von Willebrand factor (VWF) resulting in impaired proteolysis and higher levels of VWF, and consequently higher factor VIII plasma levels in individuals with a non-O blood type than in blood group O individuals9.

Considering this association along with the finding that cardiovascular mortality is the first cause of death in men, it is not surprising that investigators have assessed whether ABO blood group correlates with life-expectancy10–12. However, as the investigations gave conflicting results, we decided to analyse such an association at our city hospital.

Material and methods

Population data

A retrospective review of electronic clinical records was conducted for all subjects (outpatients and blood donors) who underwent ABO blood typing during the period from January 2010 to December 2013 at the Department of Haematology and Transfusion Medicine of Mantua. In all individuals evaluated, ABO blood type, age and gender were recorded. Age at the time of the observation was discretized into 11 age groups (0 to 10): age between 0–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89, 90–99, and >99 years.

Statistical analysis

The mean age in females and males was compared by means of Student’s t-test. The correlation between blood groups and gender was evaluated using Pearson’s chi squared test on each of the O, A, AB and B groups. The changes of the frequencies of blood groups in various age groups were assessed with a test for trend, splitting the population by gender. The outcome was the odds of each blood group, where odds=P/(1−P), and P is the proportion of each blood group. The test computed a chi-squared test of homogeneity of odds (equal odds) and a test for linear trend of the log odds against the numerical code used for the categories of age. This investigation was applied to subjects between age 20 and age 99, comprising 26,788 observations. The same matter was investigated with a logistic approach, using each blood group frequency as a dependent variable, focusing on age as the main predictor, and adjusting for gender. The interaction age*gender was also added to the covariate list. The above age limits were maintained. All estimates were computed with Stata 13.1 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

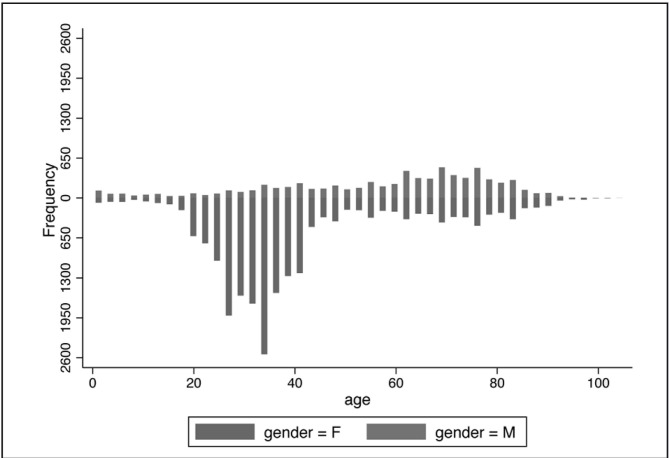

During the four-year study period, a cohort of 28,129 subjects presenting at our Institution as outpatients or as blood donors was collected. Of these subjects, 20,897 were female and 7,231 were males. The summary data of the population are reported in Table I. The subjects’ ages spanned from 0 to 103 years. The mean age in females was 40.8 years whereas that in males was 57.2 years (p<0.0001). The age distribution showed a bimodal pattern both in females and in males (Figure 1). Comparison of the pattern of age distributions showed a female excess in the childbearing age.

Table I.

Characteristics of the population analysed, stratified by decades of age.

| Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Age | Group | Number | % | Number | % |

| <10 | O | 81 | 34.91% | 125 | 42.09% |

| A | 102 | 43.97% | 123 | 41.41% | |

| AB | 17 | 7.33% | 15 | 5.05% | |

| B | 32 | 13.79% | 34 | 11.45% | |

| Total | 232 | 297 | |||

|

| |||||

| 10–19 | O | 206 | 34.51% | 83 | 40.69% |

| A | 246 | 41.21% | 90 | 44.12% | |

| AB | 51 | 8.54% | 10 | 4.90% | |

| B | 94 | 15.75% | 21 | 10.29% | |

| Total | 597 | 204 | |||

|

| |||||

| 20–29 | O | 2,050 | 41.73% | 127 | 37.13% |

| A | 1,700 | 34.60% | 151 | 44.15% | |

| AB | 287 | 5.84% | 14 | 4.09% | |

| B | 876 | 17.83% | 50 | 14.62% | |

| Total | 4,913 | 342 | |||

|

| |||||

| 30–39 | O | 3,280 | 41.62% | 312 | 42.80% |

| A | 3,223 | 40.90% | 306 | 41.98% | |

| AB | 325 | 4.12% | 26 | 3.57% | |

| B | 1,052 | 13.35% | 85 | 11.66% | |

| Total | 7,880 | 729 | |||

|

| |||||

| 40–49 | O | 1,006 | 42.13% | 304 | 41.03% |

| A | 1,008 | 42.21% | 308 | 41.57% | |

| AB | 101 | 4.23% | 32 | 4.32% | |

| B | 273 | 11.43% | 97 | 13.09% | |

| Total | 2,388 | 741 | |||

|

| |||||

| 50–59 | O | 434 | 41.65% | 343 | 40.16% |

| A | 458 | 43.95% | 371 | 43.44% | |

| AB | 43 | 4.13% | 42 | 4.92% | |

| B | 107 | 10.27% | 98 | 11.48% | |

| Total | 1,042 | 854 | |||

|

| |||||

| 60–69 | 0 | 515 | 42.28% | 622 | 41.00% |

| A | 545 | 44.75% | 679 | 44.76% | |

| AB | 38 | 3.12% | 67 | 4.42% | |

| B | 120 | 9.85% | 149 | 9.82% | |

| Total | 1,218 | 1,517 | |||

|

| |||||

| 70–79 | O | 588 | 39.46% | 715 | 42.66% |

| A | 693 | 46.51% | 725 | 43.26% | |

| AB | 56 | 3.76% | 68 | 4.06% | |

| B | 153 | 10.27% | 168 | 10.02% | |

| Total | 1,490 | 1,676 | |||

|

| |||||

| 80–89 | O | 422 | 43.60% | 331 | 42.01% |

| A | 416 | 42.98% | 349 | 44.29% | |

| AB | 38 | 3.93% | 41 | 5.20% | |

| B | 92 | 9.50% | 67 | 8.50% | |

| Total | 968 | 788 | |||

|

| |||||

| 90–99 | O | 66 | 40.99% | 37 | 45.68% |

| A | 70 | 43.48% | 36 | 44.44% | |

| AB | 8 | 4.97% | 3 | 3.70% | |

| B | 17 | 10.56% | 5 | 6.17% | |

| Total | 161 | 81 | |||

|

| |||||

| >99 | O | 6 | 75.00% | 1 | 50.00% |

| A | 2 | 25.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| AB | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 50.00% | |

| B | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Total | 8 | 2 | |||

|

| |||||

| Total | O | 8,654 | 41.41% | 3,000 | 41.49% |

| A | 8,463 | 40.50% | 3,138 | 43.40% | |

| AB | 964 | 4.61% | 319 | 4.41% | |

| B | 2,816 | 13.48% | 774 | 10.70% | |

| Total | 20,897 | 7,231 | |||

Figure 1.

Age distribution in females (F) and males (M).

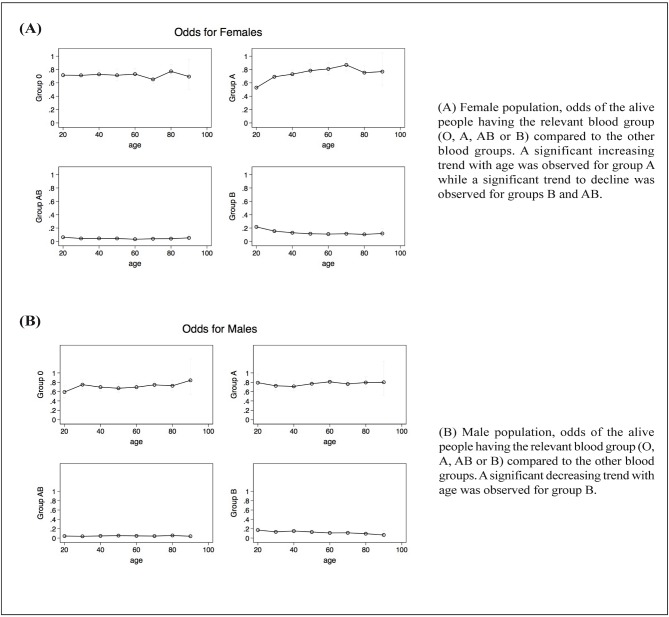

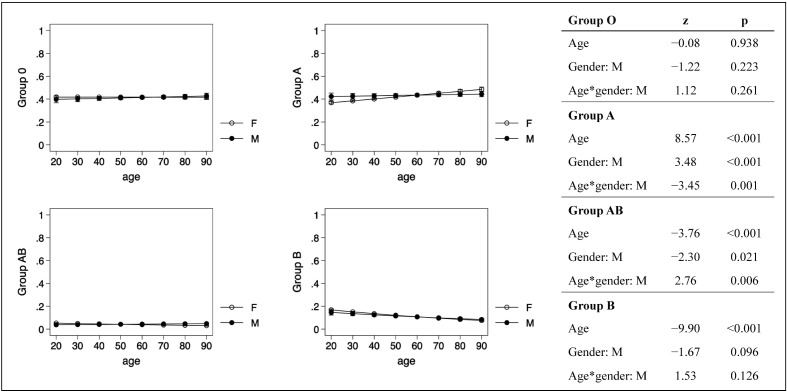

A significant association between male gender and blood group A was found (frequency: 43.40% in males, 40.50% in females; p<0.001). A similar, but inverted, association was found for group B (frequency: 10.70% in males, 13.48% in females; p<0.001). No significant differences related to gender were detected for groups O and AB. The test for trend with age produced the inferential estimates reported in Table II. In the female population, the group A frequency, measured as odds, exhibited a significant trend to increase with age, whereas the frequencies of groups AB and B manifested a significant trend to decline (Figure 2a). In the male population, only group B exhibited a significant trend to change (decrease) with age (Figure 2b). Interestingly, seven out of the ten subjects aged >99 years had blood group O, although this result did not reach statistical significance (Fisher’s exact test). Using a logistic approach, age had an increasing effect on group A, decreasing on groups AB and B, with significant differences between the two genders for groups A and AB, as shown in Figure 3.

Table II.

Blood group prevalence trend with age according to gender.

| Group O | Group A | Group AB | Group B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Homogeneity | NS | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 |

| Trend | NS | p<0.0001 | p=0.0002 | p<0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Males | Homogeneity | NS | NS | NS | p=0.0084 |

| Trend | NS | NS | NS | p=0.0001 | |

In females, group A showed a significant increasing trend, while groups AB and B showed a significant decreasing trend with age.

In males, group B showed a significant decreasing trend with age.

NS: not significant.

Figure 2.

Changes in blood group frequencies according to age and gender.

Figure 3.

Predictions of blood group probabilities by age and gender: logistic regression.

“z” is the ratio between the regression coefficient and the corresponding standard error; from “z” stems the probability “p” of coefficient=zero. The age had an increasing effect on group A, decreasing on groups AB and B. The differences between the two genders were significant for groups A and AB.

F: females; M: males.

Discussion

It has been known for many years that the ABO blood type has a profound influence on haemostasis, being a major determinant of VWF and, consequently, of factor VIII plasma levels13,14. In particular, VWF levels are approximately 25% higher in individuals who have any blood group other than O14. As VWF and factor VIII are well-established risk factors for thrombosis15,16, it is understandable that a number of experimental and clinical studies have assessed whether ABO blood type could influence the risk of developing arterial or venous thrombotic events and, ultimately, human longevity17. To verify this latter issue, we performed a large retrospective survey on more than 28,000 individuals stratifying their blood group according to age and gender. Interestingly, we observed that while the number of subjects with group A increased with age, the numbers with group AB and B decreased, indicating a negative association between these blood types and longevity. Interestingly, our findings are partially in accordance with those published by Brecher and colleagues11, whose study design was similar to that utilised in our research. Indeed, the authors retrospectively reviewed blood group distribution in a cohort of patients stratified by decade of death and found that patients with group B blood had an overall decreased survival (p<0.01) compared with patients with the other blood groups. However, the results of our investigation and that by Brecher and colleagues are not in accordance with those from other studies. For instance, Shimizu and colleagues10 analysed the ABO blood type frequency in 269 centenarians and 7,153 controls and found that blood type B was statistically more frequent among centenarians than among controls (29.4% vs 21.9%, p=0.04). No association between ABO blood group and longevity was observed by Vasto and colleagues12 in a study on 38 centenarians and 59 healthy controls. Differences in the design of the various studies (the studies by Shimizu and colleagues10 and Vasto and colleagues12 were focused exclusively on extremely old subjects) may account for the discrepancies of the findings. Interestingly, a high proportion of centenarians in our cohort (70%) were of O blood type, which has been found in several studies and meta-analyses to protect from cardiovascular diseases and cancers (e.g., pancreatic and gastric cancers)17.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our retrospective survey showed that the percentage of people with group B blood declined with age. Group AB also had a negative correlation with age, although this was less pronounced: indeed, its effects were conditioned by gender, being significant only in females. The proportion of subjects with group A blood increased with age, but again this effect was significant only in females. Thus a conditioning effect of gender was evident for both A and AB groups. We have no explanations for these observations, although an association between B blood type and some aging-associated degenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, has been found18.

We are aware of the possibility of multiple potential confounding effects, which might be active in this study, but not explicitly included in the evaluation. This is an observational study of the population assisted by a Department of Haematology and Transfusion Medicine. Young adults are more often blood donors or pregnant women undergoing Rhesus incompatibility assessment; old subjects are more often patients. Thus, disease status might be associated with blood groups in a different manner in different age groups. Moreover, information on the ethnic background is missing; this variable could be related both to age and blood groups. Nevertheless, we believe that the present investigation could be viewed as an initial attempt to shed light on a topic deserving attention. Further studies on large populations of patients, with particular effort to eliminate potential confounding effects, are necessary to verify our preliminary findings.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions

CM, MF and CB designed the study. CM and MF wrote the study. CM performed statistical analysis. CR collected the data.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Storry JR, Olsson ML. The ABO blood group system revisited: a review and update. Immunohematology. 2009;25:48–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastlund T. The histo-blood group ABO system and tissue transplantation. Transfusion. 1998;38:975–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.381098440863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franchini M, Capra F, Targher G, et al. Relationship between ABO blood group and von Willebrand factor levels: from biology to clinical implications. Thromb J. 2007;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franchini M, Favaloro EJ, Targher G, Lippi G. ABO blood group, hypercoagulability, and cardiovascular and cancer risk. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2012;49:137–49. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2012.708647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu O, Bayoumi N, Vickers MA, Clark P. ABO(H) blood groups and vascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:62–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dentali F, Sironi AP, Ageno W, et al. Non-O blood type is the commonest genetic risk factor for VTE: results from a meta-analysis of the literature. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:535–48. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franchini M, Makris M. Non-O blood group: an important genetic risk factor for venous thromboembolism. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:164–5. doi: 10.2450/2012.0087-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dentali F, Sironi AP, Ageno W, et al. ABO blood group and vascular disease: an update. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40:49–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franchini M, Crestani S, Frattini F, et al. ABO blood group and von Willebrand factor: biological implications. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:1273–6. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu K, Hirose N, Ebihara Y, et al. Blood type B might imply longevity. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1563–5. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brecher ME, Hay SN. ABO blood type and longevity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:86–98. doi: 10.1309/AJCPMIHJ6L3RPHZX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasto S, Caruso C, Castiglia L, et al. Blood group does not appear to affect longevity: a pilot study in centenarians from western Sicily. Biogerontol. 2011;12:467–71. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Donnell JS, Lasffan MA. The relationship between ABO histo-blood group, factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. Transfus Med. 2001;11:343–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2001.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill JC, Endres-Brooks J, Bauer PJ, et al. The effect of ABO blood group on the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Blood. 1987;69:1691–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koster T, Blann AD, Briët E, et al. Role of clotting factor VIII in effect of von Willebrand factor on occurrence of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1995;345:152–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whincup PH, Danesh J, Walker M, et al. von Willebrand factor and coronary heart disease: prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1764–70. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liumbruno GM, Franchini M. Beyond immunohaematology: the role of the ABO blood group in human diseases. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:491–9. doi: 10.2450/2013.0152-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kak VK, Gordon DS. ABO blood groups and Parkinson’s disease. Ulster Med J. 1970;39:132–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]