Abstract

Deformation-based circulating tumor cell (CTC) microchips are a representative diagnostic device for early cancer detection. This type of device usually involves a process of CTC trapping in a confined microgeometry. Further understanding of the CTC flow regime, as well as the threshold passing-through pressure, is a key to the design of deformation-based CTC filtration devices. In the present numerical study, we investigate the transitional deformation and pressure signature from surface tension dominated flow to viscous shear stress dominated flow using a droplet model. Regarding whether CTC fully blocks the channel inlet, we observe two flow regimes: CTC squeezing and shearing regime. By studying the relation of CTC deformation at the exact critical pressure point for increasing inlet velocity, three different types of cell deformation are observed: (1) hemispherical front, (2) parabolic front, and (3) elongated CTC co-flowing with carrier media. Focusing on the circular channel, we observe a first increasing and then decreasing critical pressure change with increasing flow rate. By pressure analysis, the concept of optimum velocity is proposed to explain the behavior of CTC filtration and design optimization of CTC filter. Similar behavior is also observed in channels with symmetrical cross sections like square and triangular but not in rectangular channels which only results in decreasing critical pressure.

I. INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a major public health problem all over the world.1 Decades of efforts have been engaged in controlling cancer death rates with only marginal success. According to National Cancer Institute (NCI) database, cancers can be categorized into local stage, regional stage, and distant stage.2 Early detection at local stage has shown a high five-year survival rate for many kinds of cancers such as cervical cancer,3 prostate cancer,4 and pancreatic cancer.5 Detecting cancers early when treatment is most successful offers substantial benefits to patients.

There is growing evidence that circulating tumor cells (CTCs) present in the bloodstream of cancer patients are responsible for initiating cancer metastasis and can be used as a potential biomarker for early cancer detection.6–8 CTCs are tumor cells shed from primary tumors and can travel through circulation to distant metastatic sites or even self-seed into their tumors of origin.9 The detection of CTCs has important prognostic and therapeutic implications as they are found in the peripheral blood of early-stage cancer patients prior to the onset of clinical symptoms.8 A variety of technologies have been developed to separate CTCs from normal blood cells, based on the differences in cellular biochemical properties such as surface antigen expression or physical properties, such as size or deformability10 as well as differing acoustic,11,12 magnetic,13 optic,14 or dielectrophoretic characteristics.11,15–18 Among the various extant methods for CTC detection and enumeration, deformation-based CTC filtration offers the advantages of structural simplicity,19,20 stable performance, and low cost.21 For example, deformation-based CTC microfilters, such as orifice,22 weirs,20 ratchet,23 pillars,24 or membranes21-based devices, can batch-process samples of whole blood without elaborate chemical labeling25 and provide a compelling label-free26 strategy for blood purification and cancer cell capturing.

Most of the existing studies on deformation-based CTC microfilters are experimental work focusing on device design and manufacturing.15,27–29 In order to achieve high capture efficiency, high isolation purity, and high system throughput,27,30 CTC microfilter designs need to be optimized for performance. Numerical modeling can play a crucial role in increasing our ability to understand the complex cell/flow/channel interactions in the cell entrained pressure-driven flow passing through microfluidic channels and may deliver important insights into optimum design of future lab-on-a-chip devices.

Previous numerical studies have employed a liquid-droplet model for cells and reported findings on entry channel pressure influences for semi-static device design,16 with relevant pressure and deformation correlation,31,32 as well as the effect of 3D channel geometry on cell deformation.16 The pressure signature33 and possible deformation evolution under the influence of both surface tension of the cancer cell and viscous shear stresses acting on the cell at different device operating conditions remain elusive. Transitional operating conditions between surface tension-dominant and viscous shear stress-dominant flow behaviors are also characterized. Considerations important to the device design include achieving maximum filtration capability, high throughput, and high efficiency. Understanding of the interplay between the effects of interfacial, viscous, and inertial forces, as well as the balance between the viscous shear stress and surface tension,34 is essential to develop a microfilter capable of efficient, specific, and reliable capture of CTCs.

In this paper, we study the deformation of CTC, the pressure signature of CTC passing through the microfilter, and cross-section influence over a wide range of flow rates. The pressure signature of a typical CTC deformation process is investigated for four types of 3-D geometries with uniform lengthwise cross-sectional areas: circular, square, triangular, and rectangular. The numerical study is based on Continuum Surface Force (CSF) and Volume of Fluid (VOF) methods.35 The dynamic variance of CTC passing-through pressure is studied and compared for different channel geometries. These data analyses provide useful insight not only for high efficiency CTC microfilter development but also aids in understanding capillary blockage,36 cancer metastasis,37 and drug delivery processes.38

II. PROBLEM DESCRIPTION

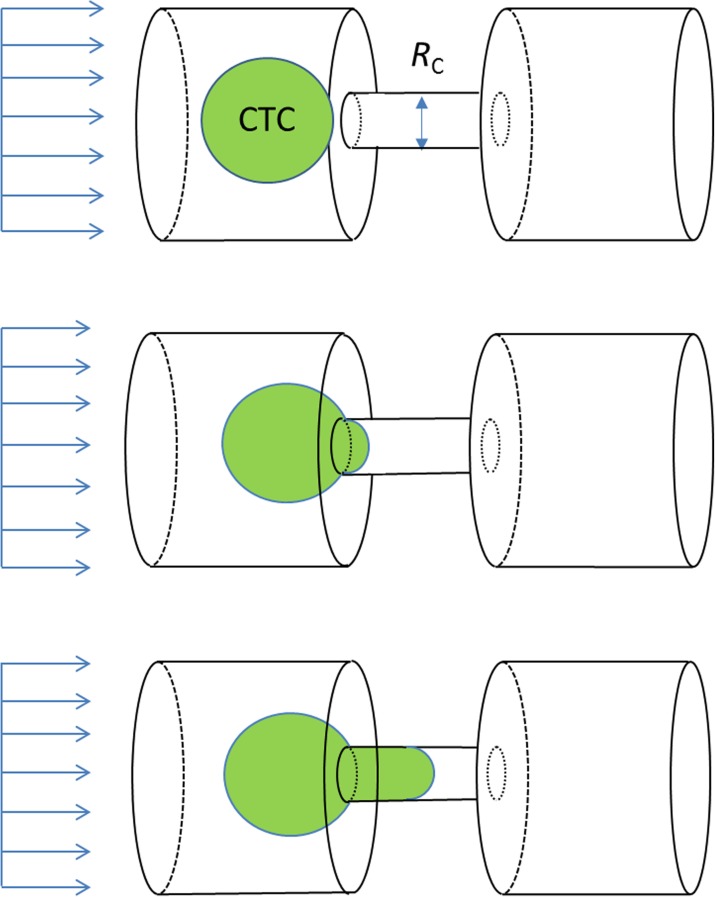

CTCs are generally stiffer than normal blood cells39 although malignant CTCs with increased metastatic potential tend to have increased deformability.40,41 Isolation of CTCs using deformation is achieved as the stiffer CTCs are quickly trapped in narrow channels when a fluid sample is injected into a microfluidic system. In the present study, we consider filtering channels with four distinct cross sectional shapes, namely, circular, square, rectangular, and triangular. Effective CTC capturing has been reported to have a critical diameter in the range of 5–12 μm for circular microfilters.20,42 A circular channel with a diameter of 5 μm is adopted as the baseline case in this study to target high filtering performance. The key dimensions of non-circular channels are determined based on arriving at the same pressure drop in the viscous channel flows as the circular baseline calculation. Fig. 1 illustrates schematically the microfiltration setup. Carrier flow and CTC proceed from the left to the right along the microchannel. The device is working on the characteristic dimensions on the order of 10 μm.

FIG. 1.

A cell passing through a filtering channel.

We model a cell, which is an aqueous core surrounded by a thin lipid bilayer membrane, as a liquid droplet. In the droplet model, the cell's ability to resist deformation is described by the surface energy (interfacial tension) of the droplet. CTCs derived from different cancer types are investigated. Table I gives the cancer cell types and their corresponding interfacial tension coefficients extracted from single cell deformability experiments reported in the literature. Note that a more deformable cell possesses a lower interfacial tension coefficient. As expected, surface tension of white blood cells (WBCs) is substantially lower than those of the stiffer cancer cells listed in Table I. The droplet model adopted here neglects the cell internal contents such as nucleus and microfilaments and neither does it account for heterogeneity of the cell nor does it allow the description of active responses exhibited by the living cell, such as rigidity sensing or cell pulsation. However, it readily allows insights into the filtration effects of different cancer cell types under various operating conditions for cell capturing. Indeed, previous studies also show that the droplet model is suitable for simulating cells especially when deformation is large.43

TABLE I.

Cell types and their interfacial tension coefficients.

The size distribution of CTCs (12–25 μm in diameter) has shown to overlap with that of normal WBCs (10–18 μm in diameter44). In our model, CTCs and WBCs are both considered to be 16 μm in diameter, to rule out effects resulting from the size differences in cells. The erythrocyte (7–8 μm in diameter44) is not considered in the study as they are highly deformable and can pass freely through any filtering channel within the design range.

III. MODELING OF TWO-PHASE FLOW WITH SURFACE TENSION

The problem under consideration consists of a dispersed phase (the cell) entrained in a continuous phase (the ambient flow) passing through a microfluidic contraction.49,50 The interface that separates the two phases can be solved using VOF,16,51 level-set,43 front-tracking,52 or phase-field method. Among these methods, the VOF method, which has superior mass conservation property, is adopted in our model to track the interface between the cell and its surrounding fluid. The VOF method uses a simple and economical way to track free surface.53 It defines and stores only a function α whose value is 1 at any point occupied by CTC and 0 otherwise. The value between 0 and 1 indicates the membrane of CTC.

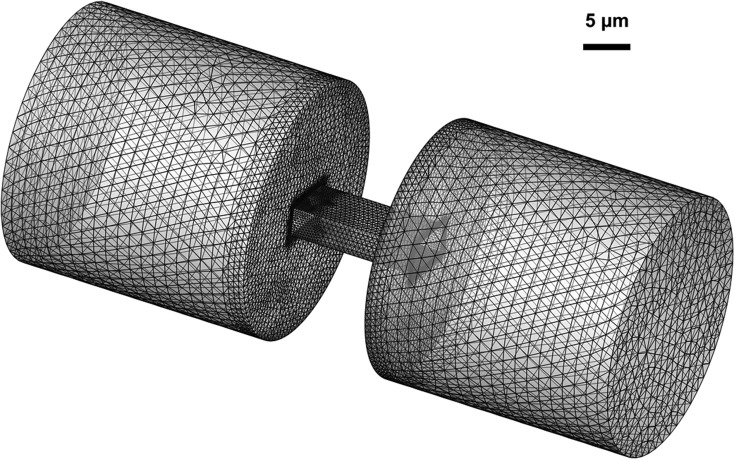

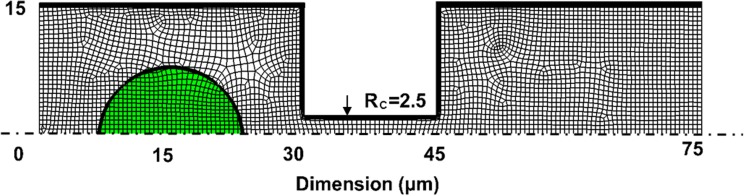

Transient simulation of a cell passing through a filtering channel is performed using the commercial software ANSYS Fluent with an explicit time stepping scheme. Inflation layers are employed to properly resolve the flow within the boundary layer. The 3-D mesh is inflated along the walls of the non-circular channels. The circular channel is modeled using a 2-D axisymmetric model as shown in Fig. 2, with inflated mesh distributed along the symmetry line as well as the channel walls. The total number of elements used for the 3-D simulation is approximately 200 000, with nearly 5000 elements patched to the cell (Fig. 3). Both CTCs and white blood cells are assumed to be incompressible.

FIG. 2.

Mesh and dimensions for circular channel. The CTC locates at 15 μm away from the filter inlet. Area patched with the volume fraction of 1 indicates the CTC.

FIG. 3.

Mesh and dimensions for the non-circular microfilter (rectangular).

The interface is tracked by solving the transport equation for the dispersed phase volume fraction α. Assuming no mass transfer between phases, the continuity equation can be written as

| (1) |

Besides the interface tracking, simulation needs to take into account surface tension effects. Our surface tension model is based on the CSF method. With this model, the addition of surface tension to the VOF calculation results in a source term in the conventional incompressible Navier-Stokes momentum equation35

| (2) |

where is the velocity vector. ρ and μ are volume-fraction-averaged density and viscosity, respectively. is the source term representing the surface tension force localized at the interface.

The surface tension force can be transformed into a volume force in the region near the interface and expressed as35

| (3) |

where σ is the interfacial tension coefficient between the dispersed phase and the continuous phase, κ is the mean curvature of the interface in the control volume, and ρ1 and ρ2 are densities of the continuous phase and the dispersed phase, respectively. The density is interpolated from .

For the incompressible two-phase flow problem, a constant volume flow rate is used as the inlet boundary condition. No-slip boundary conditions are prescribed on the channel walls. The walls are assumed to be non-wetting with respect to the dispersed phase with a 180° contact angle.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In the literature, the problem of modeling a fluid body passing through a channel confinement has mainly focused on either the influence of surface tension or the viscous shear stress on the cell or droplet.54 Briefly, droplet motion at low velocity can be described by surface-tension-dominated flow, while high-speed motion can be described as shear-stress-dominated flow. The dimensionless numbers that can be used to describe the relations of important forces include Ca and We numbers as defined in Eq. (4).

For low flow rate cases, the threshold pressure of CTC passing through a microchannel is determined by the Young-Laplace equation assuming quasi-static conditions. Examples of slow motion application of the Young-Laplace equation include micropipette aspiration55 and ratchet CTC chips.19,23 For high flow rate cases, research has been focused on the friction- and viscosity-induced non-linear droplet transport pressure.

A. CTC deformation behavior at different operational conditions

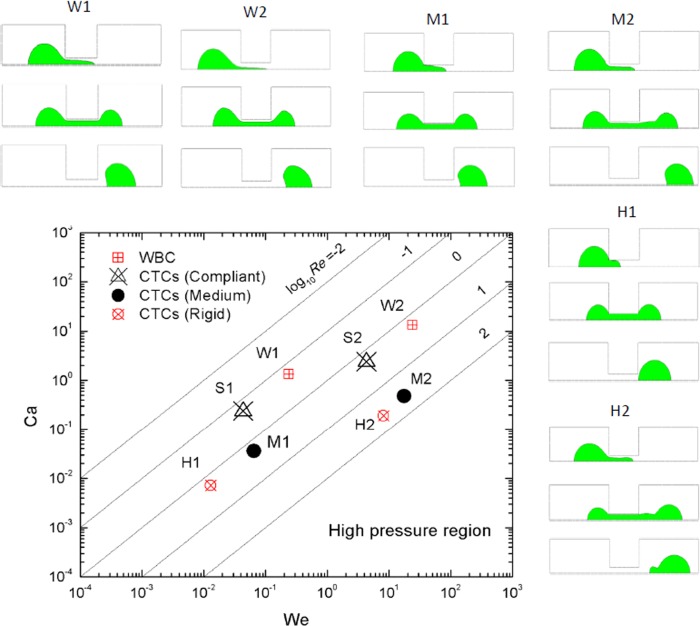

Circulating tumor cells can be categorized into three types by their stiffness: rigid, medium, and compliant, according to the list of interfacial tension coefficients in Table I. Together with extremely compliant WBC, the flow regimes of four types of cells are illustrated in Fig. 4. Three characteristic stages are selected to represent different flow regimes.

FIG. 4.

Phase chart of CTC deformation behavior. (H1) CTCs (rigid) at Re = 1.8, We = 1.3 × 10−2, flow rate 7 nl/s; (H2) CTCs (rigid) at Re = 36, We = 5.2, flow rate 140 nl/s; (M1) CTCs (medium) at Re = 0.18, We = 6.48 × 10−4, flow rate 0.7 nl/s; (M2) CTCs (medium) at Re = 3.6, We = 6.48 × 10−2, flow rate 14 nl/s; (S1) CTCs (compliant) at Re = 0.18, We = 4.3 × 10−2, flow rate 0.7 nl/s; (S2) CTCs (compliant) at Re = 1.8, We = 4.3, flow rate 7 nl/s; (W1) WBC at Re = 0.18, We = 2.4 × 10−1; and (W2) WBC at Re = 1.8, We = 24, flow rate 7 nl/s.

A flow regime chart based on dimensionless numbers is often used in multiphase flow study.56 Here, we choose the x-axis of the flow regime as the We number, and the Y-axis is selected as the Ca number, which makes the diagonal lines tilted 45° the Re number. These dimensionless numbers are defined below:

| (4) |

Here, d is the diameter of confinement channel, ρ is the density of cell, V is the velocity of carrier flow, σ is the interfacial tension coefficient of CTC, and μ is the viscosity of carrier flow.

A series of CTC deformation simulations was conducted as listed in Fig. 4. The W, S, M, and H represent white blood cells, CTCs (compliant), CTCs (medium), and CTCs (rigid), respectively. Three stages were plotted and illustrated. For purpose of pressure analysis, we are most interested in the first stage, where the maximum threshold pressure is reached. As can be seen for CTCs (rigid), we illustrated the cell deformation at four different flow rates. (H1) deformation is a representative of CTCs (rigid) passing through the microfilter at an extremely low velocity. Since the viscous shear stress influence is negligible, the deformation of the cell front at critical pressure follows a spherical shape and the cell is squeezed into the confinement channel. (H2) deformation shows an elongated cell front, and the cell is detached from the wall of the microchannel, resulting in co-flow of the carrier fluid inside the filtering channel. In this case, the cell is sheared into the confinement channel. Similar phenomena can be observed for other classes of cell stiffness. Deformation at (S1) and (M1) represents that cells being squeezed through the channel without co-flow of carrier fluid. Design at this stage should focus on CTC experiencing “friction”40 with the wall of channel.57 With increasing velocity, for deformation at (W2), (S2), and (M2), the carrier fluid begins to co-flow with CTC resulting in shear dominated flow. Fig. 5 further illustrates the detailed flow streamlines at the stage when threshold pressure is reached at three different flow rates for CTCs (rigid). We found the behavior of CTCs (compliant) predictable by studying WBC and CTCs (medium). Deformation behavior of CTCs (compliant) is more like WBC.

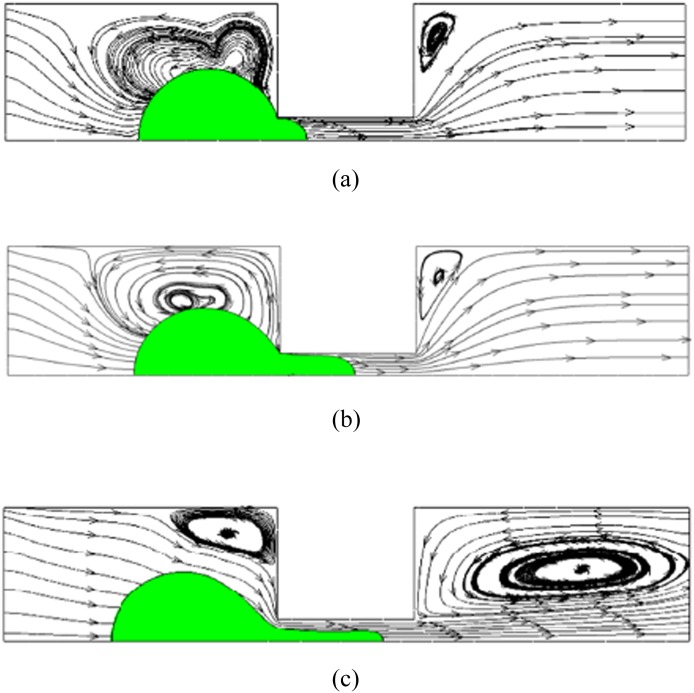

FIG. 5.

Streamline and CTC deformation behavior for flow rate of 7 nl/s, 77 nl/s, and 140 nl/s for cervical cancer, respectively. (a) CTC deformation at low flow rate (7 nl/s), the squeezing regime dominated by Young-Laplace equation. (b) CTC deformation at optimum flow rate (77 nl/s). If a higher flow rate is used, the cell may detach from the filter and allow carrier fluid co-flow through the filtration channel. (c) CTC deformation at high flow rate (140 nl/s). Carrier fluid exhibits co-flows while the CTC passes through the channel.

If the velocity is small enough, the CTC deformation follows spherical deformation when passing through the channel as in Fig. 5(a). The cell is passing with wall friction51 at a low Re number. This is the so called “squeezing regime,” and the process of CTC passing is similar to the micropipette aspiration that has been described previously.55,58 With increasing Re, shear force begins to dominate, and the front end of CTC will follow a parabolic shape as in Fig. 5(b). With even higher Re, a complete cell-wall detachment will happen, a situation that helps high speed cell passing, and the CTC front end becomes extremely thin and elongated.

B. Maximum passing pressure at different operational conditions

Deformation-based CTC detection uses pressure-driven flow for cell capturing. For static pressure analysis,16 the total inlet pressure, Pt, during a cell passing through a channel is mainly used to overcome two types of resistance: (1) viscous resistance and (2) resistance caused by cell deformation Pcell (due to surface tension),

| (5) |

The viscous pressure involves major and minor losses,59

| (6) |

The first term on the right is the viscous pressure drop along the channel, η is the viscosity coefficient, and L is the length of microfilter channel. Besides, and are the constriction and expansion coefficient, respectively. V is the average flow velocity in the filtering channel.

When a cell is passing through the filter, the pressure will increase first as the cell is getting squeezed and then will decrease as the cell is exiting the filter. Here, we define the maximum increase in pressure in the filter as critical pressure.

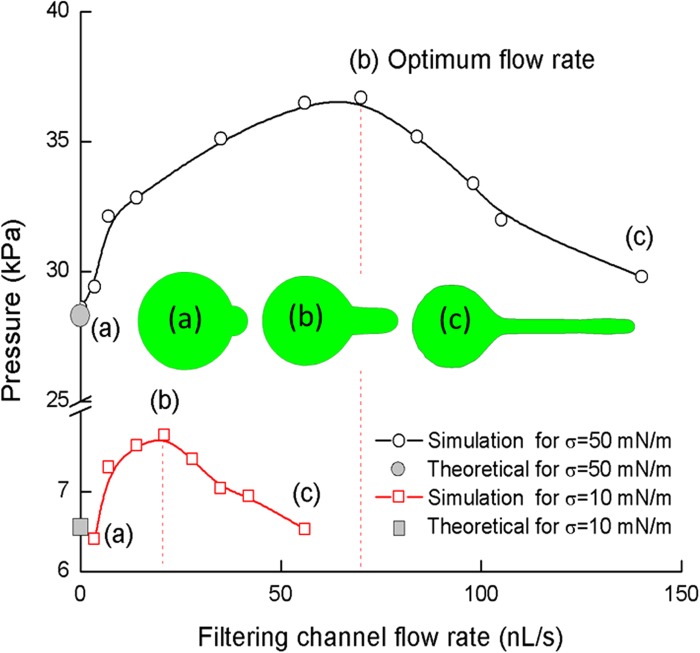

Further simulation observation collects the CTC deformation and filtration critical pressure together at a wide range of flow velocity in Fig. 6. As seen in Fig. 6, with increasing of flow rate, there is a maximum critical pressure for both cells with interfacial tension coefficients of 10 mN/m and 50 mN/m. Similar behavior is observed for cells with different interfacial tension coefficients.

FIG. 6.

Critical pressure with the influence of channel flow rate. The deformations are (a) critical pressure at low flow rate, (b) critical pressure at optimum velocity, and (c) critical pressure at high flow rate with CTC co-flow with the carrier fluid. Insets (a), (b), and (c) show a schematic plot of CTC deformation on each characteristic stage.

Illustrated in Fig. 6, we can understand that the critical pressure is primarily dominated by the CTC surface tension, which implies that critical pressure increase is mainly caused by the increase in leading-edge curvature (e.g., from spherical to parabolic-like shape). With increasing flow speed, the cell will start to detach from the channel wall, and the critical pressure reaches a maximum value—we define this flow velocity as optimum velocity (Vcr), which is dependent on cell type and surface tension.

At optimum velocity, the dynamic pressure in the carrier fluid is just strong enough to overcome the surface tension force generated by the CTC front. After the velocity is higher than the optimum velocity, the carrier fluid pressure will overcome the surface tension of CTC. Consequently, the carrier fluid will co-flow with the CTC. With a further increase in flow rate, the gap between the CTC and the microfilter wall becomes larger, CTC passthrough resistance, as well as the filtering capabilities of the device decrease accordingly.

C. Cell specific optimum operational conditions

Motivated by these observations, we wish to find the maximum filtering ability of a microfilter for certain types of CTC for earlier and more specific CTC detection. According to Fig. 6, very compliant CTCs with a low interfacial tension coefficient follow the carrier flow well when entering the microfilter channel, and accordingly, the radius of curvature of compliant CTCs at the filter is difficult to estimate. Rigid CTCs maintain a spherical front well under pressure, and membrane curvature is thus easier to estimate.

Assuming that a narrow lubrication film exists before the cell fully blocks the channel, we can estimate the optimum velocity by equating the surface tension pressure to pressure drop in the lubrication film, which includes the pressure drop due to kinetic energy increase, i.e., loss in dynamic pressure and the viscous loss in the liquid film between the cell and the channel wall. VA is flow velocity at the CTC front. Assuming the thickness of the lubrication film is ε, and the viscous shear stress in the channel can be estimated to be as , with an area along the flow direction and an area perpendicular to the flow direction . Therefore, the pressure drop caused by the lubrication film is estimated by .

By combining the relation of the static pressure, lubrication film pressure drop, and the dynamic pressure of the carrier flow, we can obtain the following equation for optimum velocity:

| (7) |

At a velocity just high enough to cause CTC yield to carrier fluid, the pressure is the highest critical pressure and flow rate Q in the film is zero. Assuming fully developed flow in the confinement channel, the velocity at the front of CTC VA along the centerline of the channel is twice the average velocity in the confinement channel.

From Eq. (7), we can see the optimum velocity (average velocity in the confinement channel) for CTC and can be described by the following equation:

| (8) |

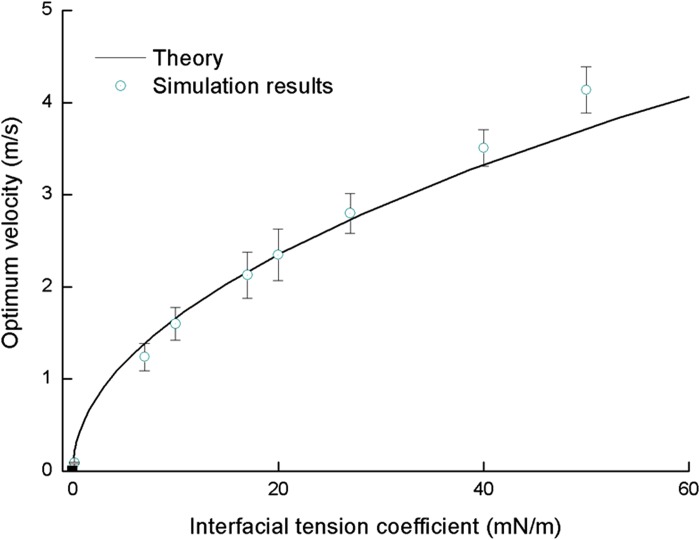

When the velocity is higher than optimum velocity, we predict the existence of co-flow of CTC and carrier fluid and a decreasing of CTC filtration pressure. Theoretical relation in Fig. 7 is plotted from Eq. (8).

FIG. 7.

Surface tension-optimum velocity relation. The velocity is obtained by repeated determination of two velocities. V− < Vcr < V+, V− represents the velocity at which a cell is squeezed through the channel, and V+ represents the velocity at which a cell is sheared through the channel. The criterion for detachment is selected as lubrication film less than one mesh thickness near the wall of filter.

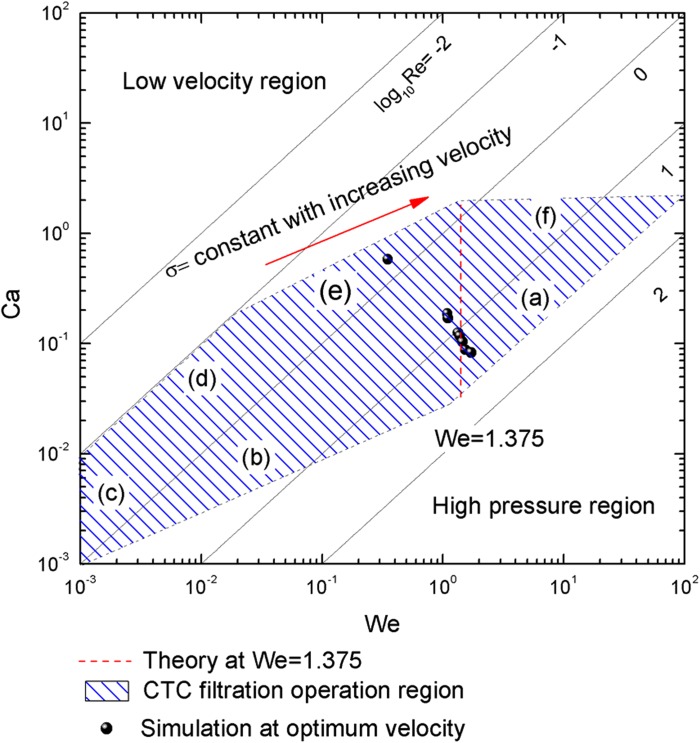

In Fig. 8, we plotted the phase chart again to indicate typical operational parameter of a deformation based CTC microfilter. The optimum velocity should be a vertical line in the phase chart. Indeed, for the CTC of the parameter of 16 μm, microfilter channel of the diameter of 5 μm, the critical We number can be calculated by Eqs. (4) and (8), . For our case Wec = 1.375, which indicates that the transition happens when inertial force is comparable to surface tension force. However, our model becomes less accurate for extremely soft cells (white blood cell) when searching for the optimum velocity. This is probably due to too small a value for surface tension and errors involved in the detachment criterion (as explained in caption of Fig. 7).

FIG. 8.

CTC detection operation chart. CTCs with a surface tension coefficient higher than 7 mN/m show an optimum velocity near We = 1.375. However, the compliant CTCs have smaller optimum velocity values than predicted.

There are several physical and engineering constrains for CTC lab-on-a-chip device design.

-

(1)

The total pressure should be smaller than 200 kPa for typical microfluidic bonding strength, which limits the operating flow rate.

-

(2)

Acceptable time duration (ideally < 1 h) for processing a standard sized blood sample (8 ml).60

-

(3)

Interfacial tension coefficient value of different cells.

These constrains give the shaded area on the flow regime chart in Fig. 8, where the vertical dashed line indicates optimum flow velocity to obtain the highest maximum passing pressure.

Further derivation yields the following expression among dimensionless numbers, which helps to define the boundaries of (b) and (e) in Fig. 8,

| (9) |

Equation (10) indicates that contours of constant σ, i.e., a specific cell type, are tilted lines with a slope of ½, which helps to explain the data distribution in Fig. 4.

We can get the corresponding boundary under the confinement of the following Ca, We, Re limit due to the confinement above. Re spans the range of Re ϵ (10−2, 102), suggesting the time duration of processing time. The lower limit reflects slow processing tolerance and the high Re reflects a high pressure limit by limitation (1).

D. Effects of 3D geometry on maximum passing pressure

Previous results show that due to the shear flow, the Young-Laplace equation does not accurately describe a non-circular channel. Channel geometry was found to be influential on static Laplace pressure prediction for the dynamic process.16 The influence of channel geometry on pressure31 and deformation32 in a low speed dynamic process is investigated for circular, square, triangular, and rectangular16 channel cross-sections. Circular,61 square,51,62,63 and rectangular cross-section channels have been extensively investigated, but triangular channel has not been well-studied due to difficulties in manufacturing.

Based on the Young-Laplace analysis, the maximum passing pressure for a non-circular channel is given by59

| (10) |

Cpw is the wet perimeter of cross-section; AP is the area of cross-section. Theoretical calculation of critical surface tension can be obtained from the previous reference.

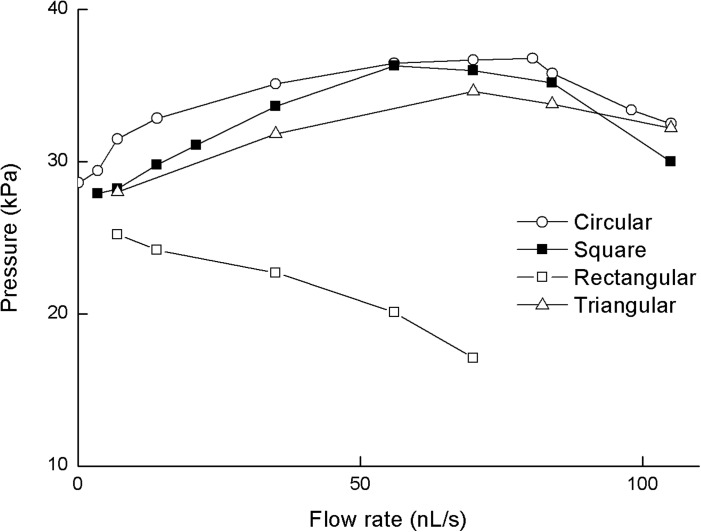

The values of passing pressure for a cell entering a microchannel of particular channel cross-section are plotted in Fig. 9. The x-axis is the normalized time for ease of comparison.

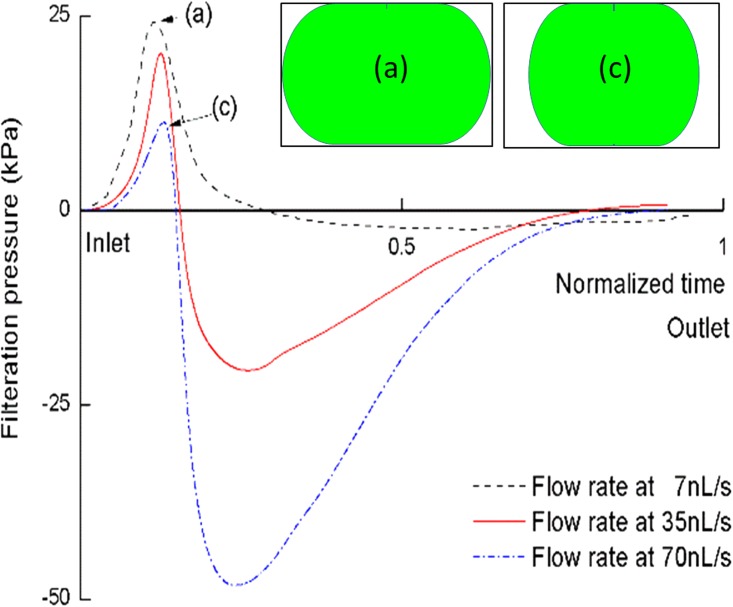

FIG. 9.

Optimum velocity-flow rate relation for four microchannel cross-sections: circular, square, triangular, and rectangular for a CTC with interfacial tension coefficient of 50 mN/m.

As seen in Fig. 9, optimum velocity is observed to influence the filtration pressure of CTC entering a microfilter channels. For these three types of channels, maximum passing pressure increases first with increasing velocity and then decreases after the optimum velocity. However, such behavior is not observed in a rectangular channel with an aspect ratio of 2. For this rectangular cross-section, the pressure continues to decrease with increasing inlet velocity; no optimum velocity is observed as in the other cross-sections. This is due to a lubrication film64,65 of carrier fluid between the cell and wall. It is filled with the carrier fluid and confined by the cell and wall. As seen in Fig. 10, due to the anisotropic elongation of the cell body, the cell is more easily compressed from the wider side of the channel. Thus, the lubrication film becomes larger and pressure in the channel drops. Consequently, the cell may pass more easily through the microfilter.

FIG. 10.

Dynamic pressure signature for of a CTC passing through a rectangular microchannel with aspect ratio of 2. The x-axis is the normalized time: 0 stands for the starting point of cell entering and 1 stands for the cell recovery to sphere. The y-axis is the filtration pressure, which is the difference between inlet pressure and the viscous pressure drop.

Note that the negative filtration pressure occurs when the net surface tension force changes its direction. Initially, this net force is resisting the flow when the cell is entering the filter. Afterwards, this force changes direction and helps to pull the remaining cell out of the filter into the exiting chamber. Rather than roundness, a microchannel can be characterized by the order of rotational symmetry—the number of equal sides a regular polygon has. For a regular polygon, channels with an order of rotational symmetry greater than 2 have an advantage in CTC filtering.

V. CONCLUSION

In this study, the transition condition of soft matter CTC is conducted numerically using the droplet model. We have demonstrated the deformation evolution of CTC in various microchannel confinements and under different flow conditions. A phase chart for CTC deformation is obtained. The velocity variation line for a specific cell is found to be linear in We-Ca log-log coordinates with slope of ½. Also, two different flow regimes of CTC entering a confined microchannel are observed: (1) cell squeezing with no carrier fluid lubrication film and (2) cell shearing with co-flow of carrier fluid. Correspondingly, there are mainly three types of CTC profile at critical pressure (1) hemisphere CTC front with CTC fully blocks channel inlet, (2) parabolic profile at higher speed with also fully blocked inlet, and (3) extreme elongation of CTC with a surrounding carrier flow. Moreover, the maximum passing pressure is also observed to vary with the increase of inlet velocity. For circular channel and square channel, the maximum passing pressure increases first then decreases after optimum velocity. However, for a rectangular channel, the maximum passing pressure decreases continuously with the increase of inlet velocity. No optimum velocity is observed. Finally, the optimum velocity is discussed and expressed with numerical verification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Adam Popma for proofreading the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel R., Ma J., Zou Z., and Jemal A., “ Cancer statistics, 2014,” Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 64, 9 (2014). 10.3322/caac.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin J. S., Hunt W. C., Key C. R., and Samet J. M., “ The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients,” JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 258, 3125 (1987). 10.1001/jama.1987.03400210067027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saslow D., Runowicz C. D., Solomon D., Moscicki A. B., Smith R. A., Eyre H. J., and Cohen C., “ American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer,” Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 52, 342 (2002). 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson J.-E., Andrén O., Andersson S.-O., Dickman P. W., Holmberg L., Magnuson A., and Adami H.-O., “ Natural history of early, localized prostate cancer,” JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 291, 2713 (2004). 10.1001/jama.291.22.2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sener S. F., Fremgen A., Menck H. R., and Winchester D. P., “ Pancreatic cancer: A report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985–1995, using the National Cancer Database,” J. Am. Coll. Surg. 189, 1 (1999). 10.1016/S1072-7515(99)00075-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabbri F., Carloni S., Zoli W., Ulivi P., Gallerani G., Fici P., Chiadini E., Passardi A., Frassineti G. L., and Ragazzini A., “ Detection and recovery of circulating colon cancer cells using a dielectrophoresis-based device: KRAS mutation status in pure CTCs,” Cancer Lett. 335, 225 (2013). 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alix-Panabières C. and Pantel K., “ Technologies for detection of circulating tumor cells: Facts and vision,” Lab Chip 14, 57 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC50644D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong B. and Zu Y., “ Detecting circulating tumor cells: Current challenges and new trends,” Theranostics 3, 377 (2013). 10.7150/thno.5195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M.-Y., Oskarsson T., Acharyya S., Nguyen D. X., Zhang X. H.-F., Norton L., and Massague J., “ Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells,” Cell 139, 1315 (2009). 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hur S. C., Henderson-MacLennan N. K., McCabe E. R., and Di Carlo D., “ Deformability-based cell classification and enrichment using inertial microfluidics,” Lab Chip 11, 912 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00595a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding X., Peng Z., Lin S.-C. S., Geri M., Li S., Li P., Chen Y., Dao M., Suresh S., and Huang T. J., “ Cell separation using tilted-angle standing surface acoustic waves,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 12992 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1413325111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi J., Huang H., Stratton Z., Huang Y., and Huang T. J., “ Continuous particle separation in a microfluidic channel via standing surface acoustic waves (SSAW),” Lab Chip 9, 3354 (2009). 10.1039/b915113c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Q., Wang L., Cheng R., Mao L., Arnold R. D., Howerth E. W., Chen Z. G., and Platt S., “ Magnetic nanoparticle-based hyperthermia for head & neck cancer in mouse models,” Theranostics 2, 113 (2012). 10.7150/thno.3854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X., Chen S., Kong M., Wang Z., Costa K. D., Li R. A., and Sun D., “ Enhanced cell sorting and manipulation with combined optical tweezer and microfluidic chip technologies,” Lab Chip 11, 3656 (2011). 10.1039/c1lc20653b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riahi R., Gogoi P., Sepehri S., Zhou Y., Handique K., Godsey J., and Wang Y., “ A novel microchannel-based device to capture and analyze circulating tumor cells (CTCs) of breast cancer,” Int. J. Oncol. 44, 1870 (2014). 10.3892/ijo.2014.2353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z., Xu J., Hong B., and Chen X., “ The effects of 3D channel geometry on CTC passing pressure - towards deformability-based cancer cell separation,” Lab Chip 14, 2576 (2014). 10.1039/c4lc00301b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs A. B., Romani A., Freida D., Medoro G., Abonnenc M., Altomare L., Chartier I., Guergour D., Villiers C., and Marche P. N., “ Electronic sorting and recovery of single live cells from microlitre sized samples,” Lab Chip 6, 121 (2006). 10.1039/B505884H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alshareef M., Metrakos N., Juarez Perez E., Azer F., Yang F., Yang X., and Wang G., “ Separation of tumor cells with dielectrophoresis-based microfluidic chip,” Biomicrofluidics 7, 011803 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFaul S. M., Lin B. K., and Ma H., “ Cell separation based on size and deformability using microfluidic funnel ratchets,” Lab Chip 12, 2369 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc21045b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohamed H., Murray M., Turner J. N., and Caggana M., “ Isolation of tumor cells using size and deformation,” J. Chromatogr. A 1216, 8289 (2009). 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gossett D. R., Weaver W. M., Mach A. J., Hur S. C., Tse H. T. K., Lee W., Amini H., and Di Carlo D., “ Label-free cell separation and sorting in microfluidic systems,” Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 397, 3249 (2010). 10.1007/s00216-010-3721-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon H.-S., Kwon K., Hyun K.-A., Sim T. S., Park J. C., Lee J.-G., and Jung H.-I., “ Continual collection and re-separation of circulating tumor cells from blood using multi-stage multi-orifice flow fractionation,” Biomicrofluidics 7, 014105 (2013). 10.1063/1.4788914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Q., McFaul S. M., and Ma H., “ Deterministic microfluidic ratchet based on the deformation of individual cells,” Phys. Rev. E 83, 051910 (2011). 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.051910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagrath S., Sequist L. V., Maheswaran S., Bell D. W., Irimia D., Ulkus L., Smith M. R., Kwak E. L., Digumarthy S., and Muzikansky A., “ Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology,” Nature 450, 1235 (2007). 10.1038/nature06385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sollier E., Go D. E., Che J., Gossett D. R., O'Byrne S., Weaver W. M., Kummer N., Rettig M., Goldman J., and Nickols N., “ Size-selective collection of circulating tumor cells using Vortex technology,” Lab Chip 14, 63 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC50689D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cima I., Yee C. W., Iliescu F. S., Phyo W. M., Lim K. H., Iliescu C., and Tan M. H., “ Label-free isolation of circulating tumor cells in microfluidic devices: Current research and perspectives,” Biomicrofluidics 7, 011810 (2013). 10.1063/1.4780062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P., Stratton Z. S., Dao M., Ritz J., and Huang T. J., “ Probing circulating tumor cells in microfluidics,” Lab Chip 13, 602 (2013). 10.1039/c2lc90148j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin C., McFaul S. M., Duffy S. P., Deng X., Tavassoli P., Black P. C., and Ma H., “ Technologies for label-free separation of circulating tumor cells: from historical foundations to recent developments,” Lab Chip 14, 32 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC50625H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo J. S., Zhao Y., Schiro P. G., Ng L., Lim D. S. W., Shelby J. P., and Chiu D. T., “ Deformability considerations in filtration of biological cells,” Lab Chip 10, 837 (2010). 10.1039/b922301k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hur S. C., Mach A. J., and Di Carlo D., “ High-throughput size-based rare cell enrichment using microscale vortices,” Biomicrofluidics 5, 022206 (2011). 10.1063/1.3576780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Z., Xu J., and Chen X., “ Predictive model for the cell passing pressure in deformation-based CTC chips,” Proceedings ASME 2014 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, American Society of Mechanical Engineers ( ASME, Montreal, Canada, 2014), pp. V010T013A043–V010T013A043 10.1115/IMECE2014-37172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z., Xu J., and Chen X., “ Modeling cell deformation in CTC microfluidic filters,” Proceedings ASME 2014 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, American Society of Mechanical Engineers ( ASME, Montreal, Canada, 2014), pp. V003T003A034–V003T003A034. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nie B., Xing S., Brandt J. D., and Pan T., “ Droplet-based interfacial capacitive sensing,” Lab Chip 12, 1110 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc21168h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garstecki P., Stone H. A., and Whitesides G. M., “ Mechanism for flow-rate controlled breakup in confined geometries: A route to monodisperse emulsions,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 164501 (2005). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.164501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson J. D., Computational Fluid Dynamics ( McGraw-Hill, New York, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leshansky A., Afkhami S., Jullien M.-C., and Tabeling P., “ Obstructed breakup of slender drops in a microfluidic T junction,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 264502 (2012). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.264502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stroka K. M., Jiang H., Chen S.-H., Tong Z., Wirtz D., Sun S. X., and Konstantopoulos K., “ Water permeation drives tumor cell migration in confined microenvironments,” Cell 157, 611 (2014). 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Negrini R. and Mezzenga R., “ Diffusion, molecular separation, and drug delivery from lipid mesophases with tunable water channels,” Langmuir 28, 16455 (2012). 10.1021/la303833s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan S. J., Lakshmi R. L., Chen P., Lim W.-T., Yobas L., and Lim C. T., “ Versatile label free biochip for the detection of circulating tumor cells from peripheral blood in cancer patients,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 1701 (2010). 10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byun S., Son S., Amodei D., Cermak N., Shaw J., Kang J. H., Hecht V. C., Winslow M. M., Jacks T., and Mallick P., “ Characterizing deformability and surface friction of cancer cells,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 7580 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1218806110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preetha A., Huilgol N., and Banerjee R., “ Interfacial properties as biophysical markers of cervical cancer,” Biomed. Pharmacother. 59, 491 (2005). 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gusenbauer M., Cimrak I., Bance S., Exl L., Reichel F., Oezelt H., and Schrefl T., “ A tunable cancer cell filter using magnetic beads: Cellular and fluid dynamic simulations,” 2011.

- 43.Leong F. Y., Li Q., Lim C. T., and Chiam K.-H., “ Modeling cell entry into a micro-channel,” Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 10, 755 (2011). 10.1007/s10237-010-0271-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bronzino J. D., The Biomedical Engineering Handbook ( CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo Q., Park S., and Ma H., “ Microfluidic micropipette aspiration for measuring the deformability of single cells,” Lab Chip 12, 2687 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc40205j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winters B. S., Shepard S. R., and Foty R. A., “ Biophysical measurement of brain tumor cohesion,” Int. J. Cancer 114, 371 (2005). 10.1002/ijc.20722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez-Rodriguez D., Guevorkian K., Douezan S., and Brochard-Wyart F., “ Soft matter models of developing tissues and tumors,” Science 338, 910 (2012). 10.1126/science.1226418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliveira K., Oliveira T., Teixeira P., Azeredo J., and Oliveira R., “ Adhesion of salmonella enteritidis to stainless steel surfaces,” Braz. J. Microbiol. 38, 318 (2007). 10.1590/S1517-83822007000200026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harvie D., Davidson M., Cooper-White J., and Rudman M., “ A parametric study of droplet deformation through a microfluidic contraction: Low viscosity Newtonian droplets,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 61, 5149 (2006). 10.1016/j.ces.2006.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harvie D., Davidson M., Cooper-White J., and Rudman M., “ A parametric study of droplet deformation through a microfluidic contraction: Shear thinning liquids,” Int. J. Multiphase Flow 33, 545 (2007). 10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2006.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taha T. and Cui Z. F., “ CFD modelling of slug flow inside square capillaries,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 61, 665 (2006). 10.1016/j.ces.2005.07.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tryggvason G., Bunner B., Esmaeeli A., Juric D., Al-Rawahi N., Tauber W., Han J., Nas S., and Jan Y.-J., “ A front-tracking method for the computations of multiphase flow,” J. Comput. Phys. 169, 708 (2001). 10.1006/jcph.2001.6726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirt C. W. and Nichols B. D., “ Volume of fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries,” J. Comput. Phys. 39, 201 (1981). 10.1016/0021-9991(81)90145-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu X., Salsac A., and Barthès-Biesel D., “ Flow of a spherical capsule in a pore with circular or square cross-section,” J. Fluid Mech. 705, 176 (2012). 10.1017/jfm.2011.462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hochmuth R. M., “ Micropipette aspiration of living cells,” J. Biomech. 33, 15 (2000). 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00175-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung C., Lee M., Char K., Ahn K. H., and Lee S. J., “ Droplet dynamics passing through obstructions in confined microchannel flow,” Microfluid. Nanofluid. 9, 1151 (2010). 10.1007/s10404-010-0636-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chakraborty D., Dingari N. N., and Chakraborty S., “ Combined effects of surface roughness and wetting characteristics on the moving contact line in microchannel flows,” Langmuir 28, 16701 (2012). 10.1021/la303603c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drury J. and Dembo M., “ Hydrodynamics of micropipette aspiration,” Biophys. J. 76, 110 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77183-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruus H., Theoretical Microfluidics ( Oxford University Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karabacak N. M., Spuhler P. S., Fachin F., Lim E. J., Pai V., Ozkumur E., Martel J. M., Kojic N., Smith K., Chen P.-i., Yang J., Hwang H., Morgan B., Trautwein J., Barber T. A., Stott S. L., Maheswaran S., Kapur R., Haber D. A., and Toner M., “ Microfluidic, marker-free isolation of circulating tumor cells from blood samples,” Nat. Protoc. 9, 694 (2014). 10.1038/nprot.2014.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodges S., Jensen O., and Rallison J., “ The motion of a viscous drop through a cylindrical tube,” J. Fluid Mech. 501, 279 (2004). 10.1017/S0022112003007213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kolb W. B. and Cerro R. L., “ The motion of long bubbles in tubes of square cross section,” Phys. Fluids A 5, 1549 (1993). 10.1063/1.858832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cubaud T. and Ho C.-M., “ Transport of bubbles in square microchannels,” Phys. Fluids 16, 4575 (2004). 10.1063/1.1813871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baroud C. N., Gallaire F., and Dangla R., “ Dynamics of microfluidic droplets,” Lab Chip 10, 2032 (2010). 10.1039/c001191f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garstecki P., Gitlin I., DiLuzio W., Whitesides G. M., Kumacheva E., and Stone H. A., “ Formation of monodisperse bubbles in a microfluidic flow-focusing device,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2649 (2004). 10.1063/1.1796526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]