Abstract

Many currently licensed and commercially available human vaccines contain aluminum salts as vaccine adjuvants. A major limitation with these vaccines is that they must not be exposed to freezing temperatures during transport or storage such that the liquid vaccine freezes, because freezing causes irreversible coagulation that damages the vaccines (e.g., loss of efficacy). Therefore, vaccines that contain aluminum salts as adjuvants are formulated as liquid suspensions and are required to be kept in cold chain (2–8°C) during transport and storage. Formulating vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts into dry powder that can be readily reconstituted before injection may address the limitation. Spray freeze-drying of vaccines with low concentrations of aluminum salts and high concentrations of trehalose alone, or a mixture of sugars and amino acids, as excipients can convert vaccines containing aluminum salts into dry powder, but fails to preserve the particle size and/or immunogenicity of the vaccines. In the present study, using ovalbumin as a model antigen adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide or aluminum phosphate, a commercially available tetanus toxoid vaccine adjuvanted with potassium alum, a human hepatitis B vaccine adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide, and a human papillomavirus vaccine adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate, it was shown that vaccines containing a relatively high concentration of aluminum salts (i.e., up to ~1%, w/v, of aluminum hydroxide) can be converted into a dry powder by thin-film freezing followed by removal of the frozen solvent by lyophilization while using low levels of trehalose (i.e., as low as 2% w/v) as an excipient. Importantly, the thin-film freeze-drying process did not cause particle aggregation, nor decreased the immunogenicity of the vaccines. Moreover, repeated freezing-and-thawing of the dry vaccine powder did not cause aggregation. Thin-film freeze-drying is a viable platform technology to produce dry powders of vaccines that contain aluminum salts.

Keywords: Thin-film freezing, lyophilization, aluminum salts, antibody responses, aggregation, repeated freezing-and-thawing

1. Introduction

Some aluminum salts, including aluminum hydroxide and aluminum phosphate, have been used as human vaccine adjuvants for decades. The primary particles of aluminum hydroxide and aluminum phosphate are in the nanometer-scale. However, when dispersed in an aqueous solution, the primary particles aggregate to form larger microparticles of 1–20 µm [1, 2]. Thus, a vaccine that is prepared by binding an antigen with an aluminum salt is physically a suspension of aluminum salt particles with antigens adsorbed on them. Many currently licensed and commercially available human vaccines such as diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis, Hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus vaccines contain aluminum salts as adjuvants [3].

A major limiting factor with these vaccines is that they must not be exposed to freezing conditions during transport and storage, and are too fragile to be stable at ambient temperatures. In other words, vaccines that are adjuvanted with aluminum salts must remain stored as a liquid suspension at 2–8°C from manufacturing to being administered to patients, because inadvertently exposing the suspension to freezing temperatures causes irreversible coagulation that damages the vaccines (e.g., loss in activity and stability) [4]. Vaccines that have been incidentally exposed to freezing conditions before administration to patients must be discarded, causing significant product waste and limited utility. This is significant considering that an estimated 75–100% of the vaccine shipments are actually exposed to freezing temperatures at some points during shipment [5], resulting in costly waste and the loss of nearly half of all global vaccine supplies [6].

There is great interest in addressing this problem, and the strategies to solve it are generally two-fold. The first is to add stabilizing reagents in vaccines to prevent aggregation during freezing. For example, the Program for Appropriate Technology (PATH) and its research collaborators have shown that adding glycerin, polyethylene glycol 300, or propylene glycol into vaccines that contain aluminum salts prevents vaccine aggregation and preserves vaccine immunogenicity, even after the vaccines are subjected to multiple exposures to −20°C [4]. Zapata et al. also reported that the adsorption of polymers or surface-active agents, such as hydroxypropyl methylcellulose or polysorbate 80, on aluminum hydroxide prevents aggregation after a freeze-thaw cycle [7]. It is thought that the stabilizing agents produce a large steric repulsive region between particles and hinder particle-particle interactions [7]. However, the addition of the aforementioned excipients into a vaccine may result in a more complex formulation and increase the cost per dose of the vaccine.

Another strategy is to convert aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines into a solid form using novel freezing and/or drying techniques. Various methods, such as vacuum-foam drying [8], spray drying [9], spray freeze-drying [10], and spray freezing into liquid [11], have been previously explored to convert protein products into dry powders. Spray freeze-drying has been studied for freeze-drying vaccines that contain aluminum salts [12, 13]. For example, using vaccines that were adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide or aluminum phosphate and contained various excipients (e.g., a mixture of mannitol, glycine, and dextran, or trehalose alone at up to 10 w/v%), Maa and co-workers [10] and Clausi and co-workers [14–16] sprayed atomized liquid vaccine droplets into liquid nitrogen and then successfully lyophilized the frozen particles into dry powder. However, the spray freeze-drying and then reconstitution process either causes particle aggregations or significantly alters the immunogenicity of the vaccines [10, 14–16]. Nonetheless, it was concluded that lower aluminum concentration, higher freezing rate, and higher excipient level help minimize adjuvant agglomeration and maximize the immunogenicity of the vaccine [10, 15].

Thin-film freezing (TFF) has recently been studied for preparing stable submicron protein particles [17]. In the TFF process, a liquid (e.g., solution) is spread out on a cryogenic substrate to form a thin film in less than one second. The resultant frozen film is then dried by lyophilization. For example, Engstrom et al. produced dried protein powders with a diameter of 300 nm using TFF, and the enzyme activity of the proteins was fully preserved [17]. In the present study, the feasibility of freeze-drying vaccines that are adjuvanted with aluminum salts using TFF was tested. Ovalbumin (OVA) was initially used as a model protein antigen, and it was adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide or aluminum phosphate and lyophilized after thin-film freezing. The applicability of the thin-film freeze-drying (TFFD) in drying vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts was further validated with commercially available veterinary tetanus toxoid vaccine, human hepatitis B vaccine, and human papillomavirus quadrivalent vaccine. The vaccines were evaluated after they were subjected to TFFD and reconstitution to test whether subjecting them to TFFD and reconstitution causes particle aggregation and decreases the immunogenicity of the vaccines. Finally, the dry vaccine powders were also subjected to repeated freezing-and-thawing cycles to test whether freezing conditions cause aggregations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dried aluminum hydroxide gel (AH gel) and aluminum phosphate were from Spectrum Chemical and Laboratory Products (New Brunswick, NJ). OVA, trehalose, and Laemmli sample buffer were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bio-safe™ Coomassie blue staining solution and Bio-Rad DC™ protein assay reagents were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Alhydrogel® (2%, w/v) was from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Tetanus antitoxin concentrated/purified (TT vaccine) was from Colorado Serum Company (Denver, CO). The TT vaccine contains potassium alum (personal communication with Dr. Randall Berrier at Colorado Serum). Potassium alum is also known as potassium aluminum sulfate. Engerix-B, a human hepatitis B vaccine from GlaxoSmithKline, and Gardasil, a human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine from Merck & Co., Inc., were purchased through the University of Texas at Austin University Health Services. Engerix-B contains aluminum hydroxide (0.5 mg of aluminum per ml). Gardasil contains amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate (0.45 mg/ml of aluminum) as an adjuvant. Mouse Anti-Tetanus Toxoid IgG ELISA kit was from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX). Tetanus toxoid was from List Biologics Laboratory (Campbell, CA). Purified polyclonal horse anti-tetanus serum and guinea pig anti-tetanus IgG were from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Hertfordshire, England).

2.2. Thin-film freeze-drying (TFFD)

Three types of aluminum-containing compounds, dried aluminum hydroxide gel (USP grade) (AH gel to differentiate from commercially prepared Alhydrogel), 2% Alhydrogel®, and aluminum phosphate, were used to adsorb OVA as a model antigen. The OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide vaccine was prepared by mixing an OVA solution with an aluminum hydroxide suspension in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, 10 mM) to reach an OVA to aluminum weight ratio of 1:10. The vaccine contained 31.4 µg/ml of OVA, 0.09% of aluminum hydroxide, and 0–5% (w/v) of trehalose. The OVA-aluminum phosphate vaccine (31.4 µg/ml of OVA, 0.142% (w/v) of aluminum phosphate, and 2% (w/v) of trehalose) was prepared similarly. When the 2% Alhydrogel® was used, Alhydrogel® (25 ml) was added into a 50 ml tube, followed by the addition of 25 ml of an OVA solution (1 mg/ml) at an OVA to aluminum weight ratio of 1:10, and 1 g of trehalose to obtain a final formulation with 2% (w/v) of trehalose, ~1% (w/v) of Alhydrogel®, and 0.5 mg/ml of OVA. The samples were subjected to TFF and lyophilized as described previously [17, 18]. Briefly, the aluminum-containing vaccine suspensions were dropped onto a pre-cooled rotating cryogenic steel surface to form thin films. The thin films were removed by a steel blade. In order to avoid the overlap of two droplets, the speed at which the cryogenic steel surface, on which the vaccine suspension was dropped, was rotating was controlled at 5–7 rpm. The frozen film-like solids were collected in liquid nitrogen and dried using a VirTis Advantage bench top tray lyophilizer (The VirTis Company, Inc. Gardiner, NY). Lyophilization was performed over 72 h at pressures less than 200 mTorr, while the shelf temperature was gradually ramped from −40°C to 26°C. After lyophilization, the solid vaccine powder was quickly transferred to a sealed container and stored in a desiccator at room temperature before further use [19].

To dry TT vaccine, trehalose was added into the TT vaccine that was diluted 50-fold in PBS (pH 6.3, 10 mM) to adjust the final concentration of trehalose to 2% (w/v). The vaccine was then subjected to TFFD as mentioned above. To dry Engerix-B, trehalose was added directly into the commercial vaccine (without pre-dilution) to obtain a formulation with 2% (w/v) of trehalose, ~20 µg/ml of HBsAg, and ~500 µg/ml of aluminum, and the vaccine was then subjected to TFFD. In Engerix-B vaccine, each 1-ml adult dose contains 20 µg of HBsAg adsorbed on 0.5 mg of aluminum as aluminum hydroxide. To dry the Gardasil vaccine, 100 µl of the vaccine was diluted to 1 ml of 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride, and trehalose was added to reach a final concentration of 2% (w/v). The vaccine was then subjected to TFFD. Each 0.5-ml dose of the original Gardasil contains approximately 20 µg of HPV 6 L1 protein, 40 µg of HPV 11 L1 protein, 40 µg of HPV 16 L1 protein, and 20 µg of HPV 18 L1 protein. Each 0.5-ml dose of Gardasil also contains approximately 225 µg of aluminum as amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate.

The morphology of the vaccines in suspension was examined under an Olympus BX60 microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA). The size of particles and particle size distribution in all samples were determined using a Sympatec Helos laser diffraction instrument (Sympatec GmbH, Germany) equipped with a R3 lens. The moisture in the dried powder was measured using a Karl Fisher Titrator Aquapal III from CSC Scientific Company (Fairfax, VA).

2.3. Shelf freeze-drying

An OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) vaccine that contained 2% of trehalose (w/v), 0.09% of aluminum hydroxide, and 31.4 µg/ml of OVA in PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mM) was frozen on the shelf of a −20°C or −80°C freezer overnight and then lyophilized using a VirTis Advantage bench top tray lyophilizer as mentioned above. The dry powder was stored in a desiccator at room temperature before use.

2.4. The effect of the concentration of trehalose in vaccine on thin-film freeze-drying

To evaluate the effect of the concentration of trehalose on TFFD of vaccines, various amounts of trehalose were added into OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) in suspension (1:10, OVA vs. aluminum, w/w) to prepare formulations with 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5% of trehalose (w/v). The suspensions were then subjected to TFFD as mentioned above.

2.5. The binding efficiency of OVA to aluminum hydroxide before and after TFFD

SDS-PAGE was used to determine the binding efficiency of OVA to aluminum hydroxide before and after TFFD [20]. The OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) dry powder (OVA to aluminum ratio, 1 to 10, w/w) was reconstituted and applied on SDS-PAGE gel. As a control, OVA alone and freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension (with 2% trehalose, w/v) were also included. Samples were mixed with a Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, and 0.01% Bromophenol Blue) before applied to 7.5% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). Precision plus protein standards were also run along with the samples at 130 V for 1 h. The gel was then stained in a Bio-Safe™ Coomassie blue staining solution and scanned using a Kodak Image Station 440CF (Rochester, NY). The intensity of the protein bands in the gel was quantified using the NIH ImageJ software, and the binding efficiency was calculated by subtracting the percentage of unbound proteins (i.e., band intensity from vaccine dry powder or freshly prepared vaccine suspension) from the total proteins (i.e., band intensity of OVA alone).

The binding efficiency of the OVA to aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) was also determined by centrifuging the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide, before and after TFFD and reconstitution, at 4500 × rcf for 5 min, and measuring the concentration of the OVA in the supernatant using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent from Thermo Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) [21]. The amount of OVA bound on the aluminum hydroxide was calculated by subtracting the amount of OVA in the supernatant from the total amount of OVA added into the vaccine.

2.6. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal analyses of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) dry powder and its individual components, OVA, aluminum hydroxide (AH gel), and trehalose, were conducted using a modulated temperature DSC (Model 2920, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) [18]. Four to seven milligrams of each sample was weighed into the aluminum pans (PerkinElmer Instruments, Norwalk, CT), which were crimped subsequently. An empty aluminum pan was used as a reference. Samples were then heated at a ramp rate of 3°C/min from −30°C to 300°C. Data were analyzed using the TA Universal Analysis 2000 software (TA Instruments).

2.7. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) dry powder and freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) suspension was examined using a Zeiss Supra 40 VP scanning electron microscope in the Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology Microscopy and Imaging Facility at The University of Texas at Austin [22]. When preparing the TFFD samples for SEM, one thin layer of the dried powder was deposited on the specimen stub using a double stick carbon tape. For the freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension, the suspension was placed on the specimen stub and allowed to dry overnight. The specimen stubs with samples were then placed in the sputter coater chamber and coated with a very thin film of lead before examination.

2.8. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectrometry

The TT vaccine was dried using TFFD and reconstituted before examination. Freshly diluted TT vaccine (in a phosphate buffer) was used as a negative control. The final trehalose concentration in both samples was 2% (w/v). Fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded using a PTI Quanmaster spectrofluorimeter (Photon Technology International, Santa Clara, CA). An excitation wavelength of 290 nm was employed, and the emission spectrum was collected from 280 nm to 530 nm [23].

2.9. Repeated freeze-thawing of thin-film freeze-dried vaccine powder

The dried powders of TT vaccine, Engerix-B, and OVA-adsorbed Alhydrogel® were subjected to three cycles of freezing (−20°C for 8 h) and thawing (4°C for 16 h), reconstituted, and analyzed for particle size distribution. As controls, fresh liquid vaccines were also subjected to the same three cycles of freezing-and-thawing and examined similarly.

2.10. Animal studies

All animal studies were carried out following the National Research Council guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas at Austin. Female BALB/c mice, 6–8 weeks of age, were from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA). Mice (n = 5) were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) or the TT vaccine, freshly prepared or reconstituted from TFFD powder. For the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel), mice were immunized on days 0, 14 and 28 with 5 µg, 10 µg, or 20 µg of OVA per mouse. As controls, mice were injected with sterile PBS or OVA alone (10 µg) dissolved in PBS. For the TT vaccine, mice were immunized on days 0, 14, and 28, and the dose of TT was 3.75 Lf (flocculation units) of tetanus toxoid per mouse per injection. Sterile PBS and TT vaccine freshly diluted with 2% trehalose were used as controls. Sixteen days after the third dose, mice were bled for antibody assay. Total anti-OVA IgG levels in serum samples were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously [24]. Anti-TT IgG levels were determined using a mouse Anti-Tetanus Toxoid IgG ELISA Kit.

2.11. Tetanus toxin binding inhibition test (ToBI-test)

The ToBI-test is an in vitro assay validated to determine the activity of anti-tetanus toxoid antiserum in vaccination studies and was adapted [25–27]. Briefly, flat bottom microplates (Corning Costar, NY, NY) (PI) were blocked for 90 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 250 µl/well PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-BSA). After washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), mouse serum samples diluted 2-fold serially in Peptone diluent (i.e., 1 % peptone, 0.5% NaCl, 0.5% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20) were added into the wells (duplicate in 100 µl, starting at 1:200 dilution). Wells, in which serum samples were not added, were used as the 100% binding signal in calculating the percent binding. Subsequently, 100 µl tetanus toxoid (0.65 µg/ml diluted in 1% peptone and 0.5% Tween 20) was added into all wells. Wells without tetanus toxoid were also included as a control. These microplates were then incubated overnight. A parallel series of plates (Maxisorp® Nunc,Thermo Scientific) (P2) were coated with 2 IU/ml of purified polyclonal horse anti-tetanus serum (NIBSC 60/013, diluted in PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) and incubated overnight. The next day, these plates were blocked for 90 min with 200 µl per well of PBS-BSA. After washing with PBS-T, 100 µl of serum-toxoid mixtures in the P1 microplates were transferred to the wells in the P2 microplates and incubated for 90 min. After a third washing step, 100 µl guinea pig anti-tetanus IgG (NIBSC 10/132) was added to the wells (1:200 dilution in PBS-BSA) and incubated for 90 min. After washing with PBS-T, 100 µl of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:2000-dilution was added and incubated for 60 min. The 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) Liquid Substrate System for ELISA (100 µl, Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated in the dark for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 µl of 2N H2SO4, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The percentage of binding (of tetanus toxoid to the polyclonal horse anti-tetanus antiserum coated in P2 microplates) was reported as the OD450 values of the samples as a percentage of the OD450 values in wells with zero percent of inhibition (i.e., tetanus toxoid that was not mixed with any mouse antiserum samples).

2.12. Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using analysis of variance followed by Fischer’s protected least significant difference procedure. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 (two-tail) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thin-film freeze-drying of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide

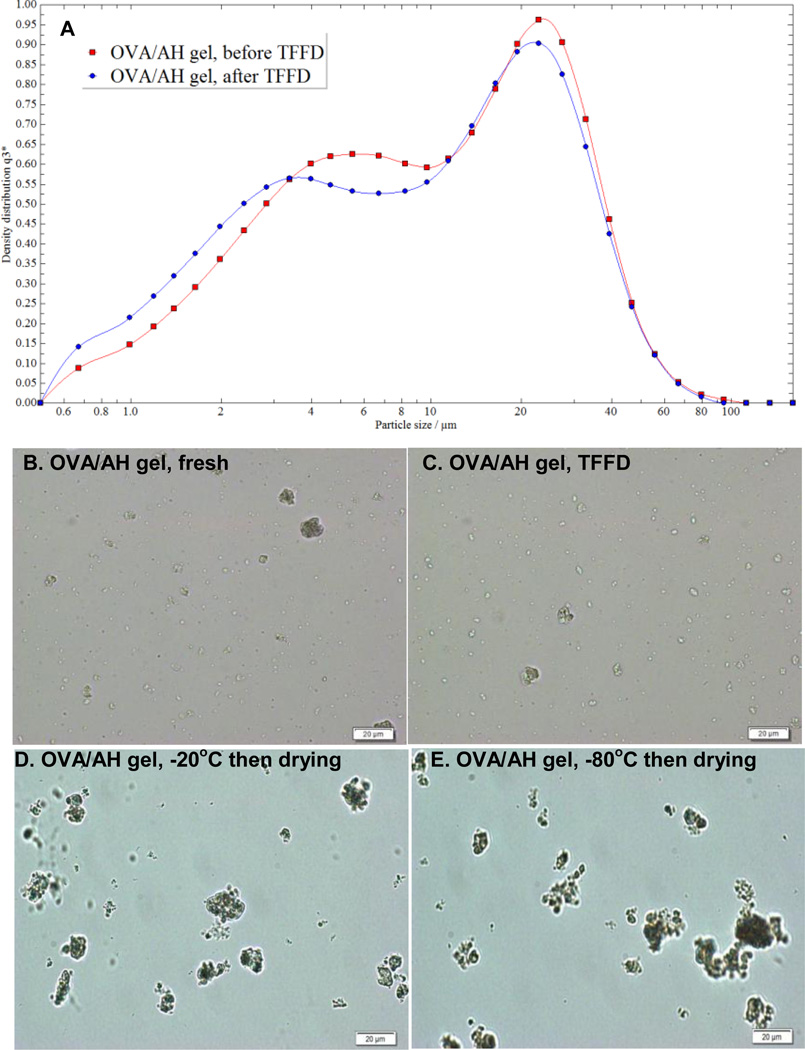

In order to test whether the TFFD can be used to lyophilize an aluminum hydroxide-adjuvanted, protein-based vaccine, OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was suspended in 2% (w/v) of trehalose and subjected to TFFD. A white powder was formed, which can be readily reconstituted with water, PBS, or normal saline with no or only minimal agitation. The moisture content in the powder was 1–3%. The size of the particles in the reconstituted OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was 9.7 ± 2.5 µm, which is not different from the size of the particles in freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension (9.4 ± 1.7 µm) (Fig. 1A), demonstrating that the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension can be successfully lyophilized into a dry powder form using TFFD without significantly affecting the size of the particles in the vaccine. The microscopic images in Figs. 1B–C also show that subjecting the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide to TFFD and reconstitution did not cause significant aggregation. In contrast, when the same OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension was frozen by placing it on a −80°C or −20°C shelf before lyophilization, significant aggregations were detected (Figs. 1D–E). Zapata et al. reported that aluminum hydroxide gel could form aggregates ranged from 65 to 160 µm after just one freeze-thaw cycle at −24°C [7]. It is thought that the particle coagulation/aggregation is due to the large water crystals formed during the slow freezing process, which bring aluminum hydroxide particles close enough to overcome repulsive forces and cause aggregation, and the original aluminum hydroxide suspension could not be reproduced upon coagulation [10]. By increasing the freezing rate, only smaller ice crystals are formed as a result of a greater rate of nucleation, which are not strong enough to overcome the repulsive forces between particles, and particle aggregation is prevented consequently [10]. In the TFF process, a solution or suspension is spread out on a cryogenic substrate to form a thin film in less than one second (cooling rate, ~100 K/s) [17], which may explain why there was not significant aggregation after the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was subjected to TFFD (and reconstitution). As mentioned early, it was reported previously that higher cooling/freezing rate helps minimize aggregation/agglomeration of vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts during freeze-drying [10, 15].

Fig. 1. TFFD of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (OVA-AH gel).

(A) Particle size distribution curves before and after the vaccine, with 2% (w/v) of trehalose, was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution.

(B–E) Representative microscopic images of OVA-AH gel with 2% trehalose (w/v) before (B) and after lyophilization and reconstitution (C–E). In C–E, the method of freezing was TFF, shelf-freezing at −20°C, and shelf-freezing at −80°C, respectively.

3.2. Thin-film freeze-drying of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide in various concentrations of trehalose

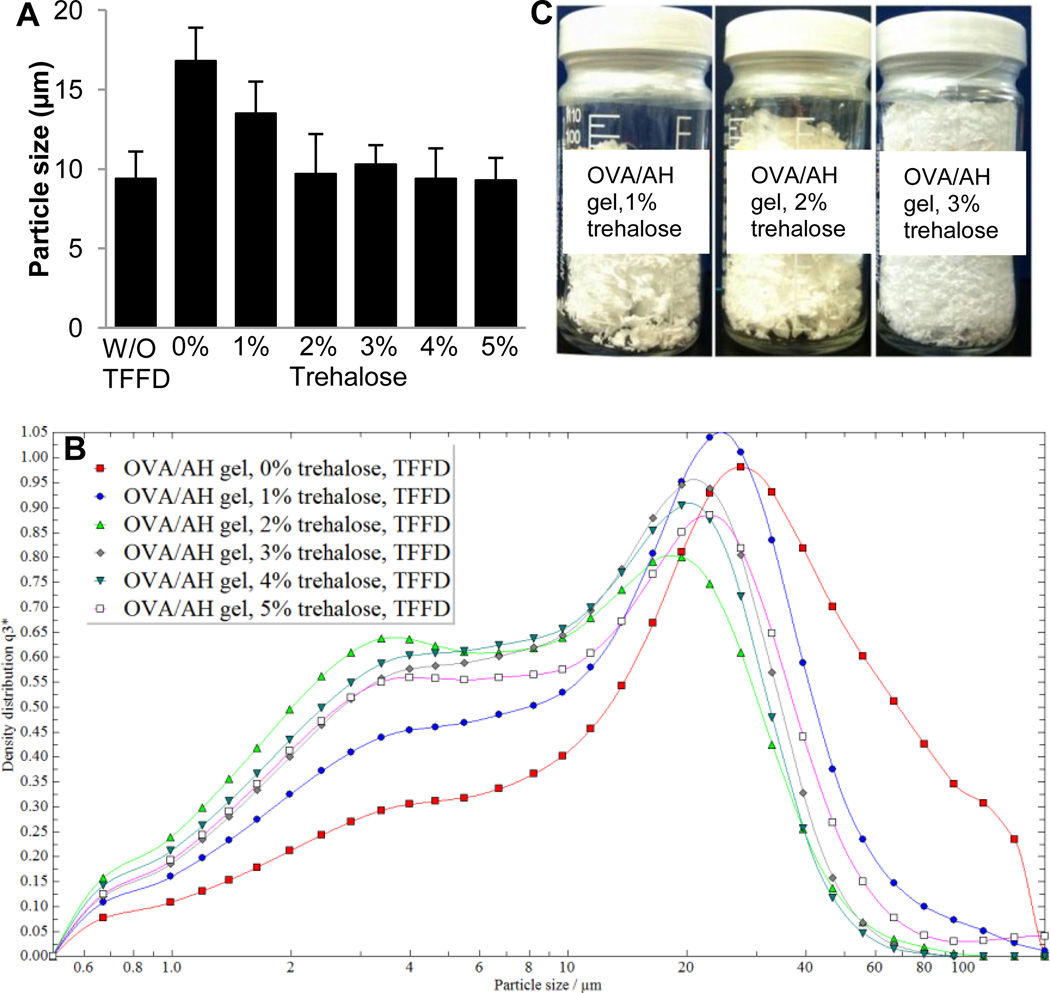

Certain sugars, such as trehalose, mannitol, dextran, and sucrose, have been shown to be effective in maintaining protein activity and stabilize aluminum salts in vaccine formulations during freezing process [13, 28, 29]. Trehalose forms fragile glass during freezing, resulting in an increase on the viscosity, which limits the mobility of protein molecules or aluminum salt particles, and thus prevents coagulation [28, 30]. The formation of glass also resulted in a trehalose-containing phase with maximum concentration that prevents the non-ice concentration or pH-induced aggregation of aluminum salts during freezing [28]. The effect of the concentration of trehalose on spray freeze-drying vaccines that contain aluminum hydroxide or aluminum phosphate was previously studied, and it was concluded that 5–20% (w/v) of trehalose is necessary to successfully spray freeze-dry vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts [16]. To determine the minimal concentration of trehalose needed to successfully lyophilize vaccine after TFF, OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) suspended in various concentrations of trehalose (i.e., 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, 5%, w/v) was subjected to TFFD. As shown in Fig. 2A, when the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension was subjected to TFFD in the absence of trehalose, the mean size of particles after reconstitution was significantly larger than that in the freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide suspension, indicating that a cryoprotectant such as trehalose is needed to successfully convert the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide into a powder by TFFD. Trehalose at 1% (w/v) was not sufficient (Fig. 2A), but 2% of trehalose was enough to help successfully convert the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide into a dry powder following TFFD, without causing particle aggregation (Fig. 2A). Shown in Fig. 2B are the particle size distribution curves of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide containing various percentages of trehalose after subjected to TFFD and reconstitution, and the representative images of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide that were subjected to TFFD with 1%, 2%, and 3% (w/v) of trehalose, respectively, are shown in Fig. 2C. In the present study, trehalose alone was used during the TFFD process. It is expected that other cryoprotectants such as sucrose, glycine and other amino acids, and polymers such as polyvinylpyrrolidone will also help prevent aggregation during the TFFD process. For example, in a previous study, Alum-HBsAg vaccine was suspended in mannitol, glycine, and dextran before spray freeze-drying [10]. The concentration of trehalose needed to successfully thin-film freeze-dry OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was only 2% (w/v) (Figs. 2A–B). Trehalose at concentrations of 7.5% or above was generally used when spray freeze-drying vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts [14–16]. Clausi et al. actually spray freeze-dried model lysozyme vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide or aluminum phosphate in 2% (w/v) of trehalose [15]. The particle size of the lysozyme vaccines increased slightly following spray freeze-drying and reconstitution, as compared to the untreated liquid lysozyme vaccines [15]. Interestingly, in the model lysozyme vaccines prepared, only 10% of the lysozymes were bound to aluminum salts, and spray freeze-drying helped increase the percent of lysozymes that adsorbed to aluminum salts [15].

Fig. 2. TFFD of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide in various concentrations of trehalose.

(A–B). Particle sizes (A) and particle size distribution curves (B) of OVA-AH gel reconstituted from powders that were thin-film freeze-dried using various concentrations of trehalose (i.e., 0–5%, w/v).

(C). Representative images of the dried OVA-AH gel powders prepared with 1%, 2%, or 3% (w/v) trehalose, respectively.

3.3. Characterization of the thin-film freeze-dried powder of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide

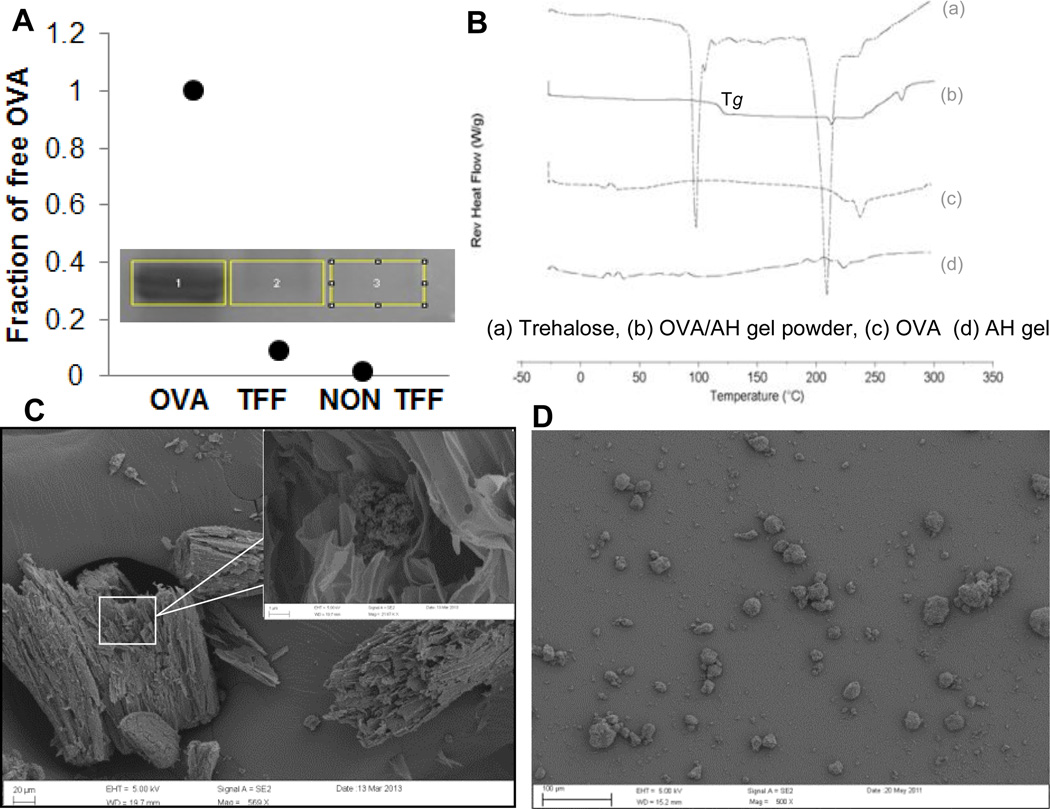

To understand the influence of the TFFD process on aluminum hydroxide-adjuvanted vaccines, several studies were conducted to characterize the dried powder of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide. The desorption of OVA from aluminum hydroxide particles (AH gel) after the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was subjected to TFFD was evaluated using SDS-PAGE. It is assumed that the intensity of the OVA band on the SDS-PAGE gel image is inversely correlated to the level of free, unbounded OVA in the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide preparation (Fig. 3A). At the OVA to aluminum weight ratio of 1:10, almost all OVA (~98.1%) were bound on the aluminum hydroxide (Fig. 3A, NON TFF). After the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution, the percent of OVA that remained adsorbed on the aluminum hydroxide was estimated to be 91.3% (Fig. 1A, TFF), suggesting that about 7% of (loosely bound) OVA was desorbed from aluminum hydroxide after the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution. The binding efficiency of the OVA to aluminum hydroxide before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution, as determined by measuring the amount of the OVA remained in the supernatant after the vaccine was subjected to centrifugation, was 50.8 ± 13.5% and 62.5 ± 8.6% (p = 0.36), respectively, which are lower than that determined using the SDS-PAGE electrophoresis mentioned above. When the centrifugation method was used, it is assumed that all OVA proteins adsorbed on aluminum hydroxide particles were precipitated after the centrifugation. When SDS-PAGE electrophoresis method was used, it is assumed that all OVA proteins that adsorbed on the aluminum hydroxide particles did not migrate out of the loading wells of the SDS-PAGE gel. The different assumptions may explain in part the different binding efficiency values obtained using those two methods. Nonetheless, it appears that subjected the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide to TFFD and reconstitution only caused minimum desorption of the OVA from the aluminum hydroxide. Finally, it is noted that in this study, sterile PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) was used to dissolve OVA and to prepare aluminum hydroxide (AH gel) suspension to minimize OVA denaturing. It was previously reported that pretreatment of aluminum hydroxide with selected concentrations of phosphate ions reduces the positive surface charge, which exists on the aluminum hydroxide at pH 7.4 [21]. The isoelectric point of OVA was reported to be around pH 4.55–4.88 [31]. Therefore, if PBS is replaced with other buffers that do not contain phosphate ions, the binding efficiency of the OVA to the aluminum hydroxide particles may increase and the ratio of the OVA to aluminum may need to be adjusted.

Fig. 3. Characterization of OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide powder prepared with TFFD.

(A). The binding efficiency of OVA to AH gel before and after TFFD (inset, OVA protein band in SDS-PAGE gel). The binding efficiency was measured after the OVA-adsorbed AH gel was subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis.

(B). DSC curves of OVA-adsorbed AH gel dry powder, OVA, trehalose, and aluminum hydroxide alone.

(C). A representative SEM image OVA-adsorbed AH gel dry powder.

(D). A representative SEM image of the freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed AH gel.

Modulated DSC was used to study the thermal properties of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide dry powder. The DSC thermogram of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide dry powder shows a glass transition temperature (Tg) of about 120°C (Fig. 3B), indicating that the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide particles suspended in trehalose solution may have formed a glass after they were subjected to TFFD [32]. The high Tg value of 120°C suggests that the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide dry powder is highly stable [33].

Shown in Fig. 3C is a representative SEM image of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide dry powder. It appears that the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide particles, which have a rough surface and irregular shape (Fig. 3D), are embedded in the bulk structure of the trehalose (Fig. 3C inset). It is likely that the trehalose surrounding the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide particles prevented the particles from interacting with one another during the freeze-drying process and prevented their aggregation.

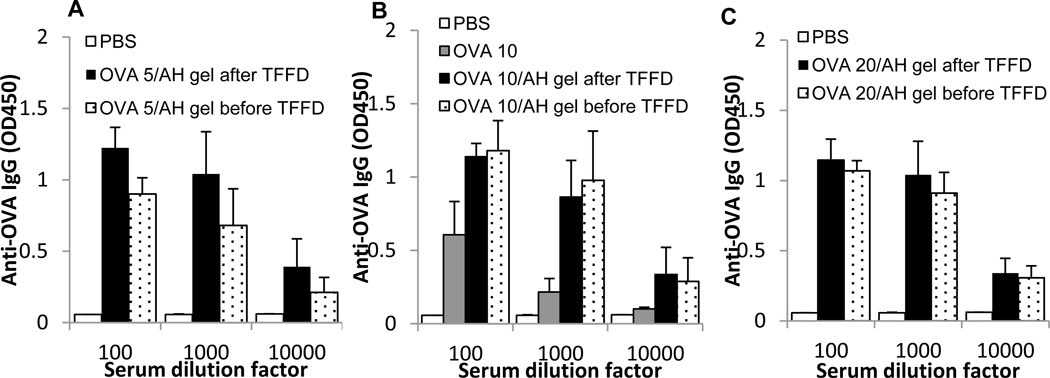

3.4. The immunogenicity of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide after thin-film freeze-drying

To test whether the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide after subjected to TFFD retained its immunogenicity, the anti-OVA immune responses induced by OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide, freshly prepared or reconstituted from TFFD powder, were evaluated in a mouse model. As shown in Fig. 4, the serum anti-OVA IgG levels in mice that were immunized with OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide following TFFD and reconstitution were not different from that in mice that were immunized with freshly prepared OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide, regardless of the dose of OVA antigen used (i.e., 5, 10, or 20 µg/mouse/injection). Clearly, the TFFD process not only avoided causing particle aggregation, but also preserved the immunogenicity of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide vaccine.

Fig. 4. Serum anti-OVA IgG levels in mice immunized with OVA-adsorbed aluminum hydroxide, before and after TFFD and reconstitution.

Female BALB/c mice (n = 5) were s.c. injected with OVA-adsorbed AH gel, before or after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution, on days 0, 14 and 28 with 5 µg (A), 10 µg (B), or 20 µg (C) of OVA per mouse. The ratio of OVA to aluminum was 1 to 10. Sterile PBS and OVA alone (10 µg) in PBS were used as controls. Total anti-OVA IgG levels in serum samples were measured 16 days after the third dose. Data shown are mean ± S.D.

3.5. Thin-film freeze-drying of OVA-adsorbed aluminum phosphate and OVA-adsorbed Alhydrogel®

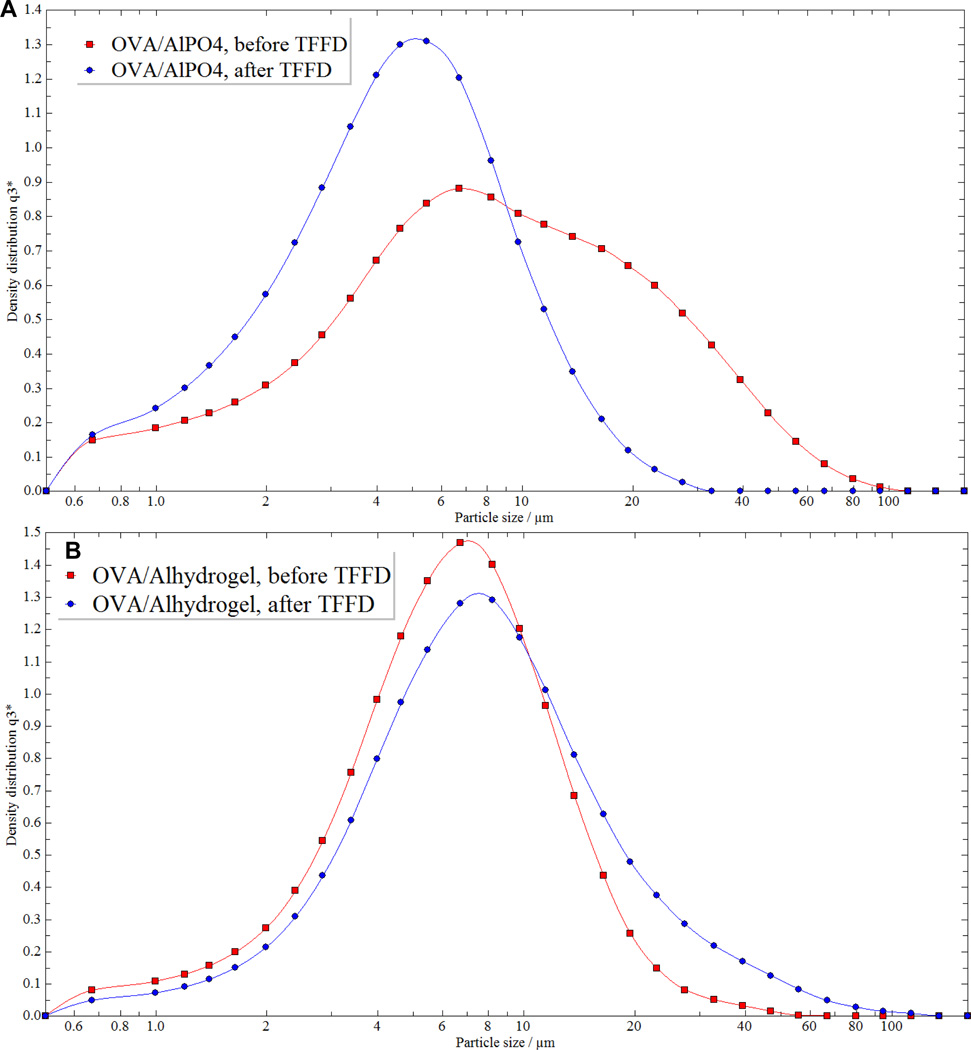

Both aluminum hydroxide and aluminum phosphate are commonly used in human vaccines. Therefore, the feasibility of using TFFD to dry a protein antigen adjuvanted with aluminum phosphate into a powder was also tested using OVA as a model antigen. Moreover, in the above studies, the aluminum hydroxide suspension (AH gel) was prepared in our own laboratories by dispersing dried aluminum hydroxide gel (USP grade) in water. Alhydrogel® (2%, w/v) is a commercially available aluminum hydroxide wet gel suspended in normal saline. Therefore, the feasibility of drying OVA-adsorbed Alhydrogel® using TFFD was also tested. Both OVA-adsorbed aluminum phosphate and OVA-adsorbed Alhydrogel® were successfully converted into powders using TFFD. Both dried samples appeared as light white-colored powder and were easily reconstituted in water with no or minimum agitation. The particle size distribution profiles of the OVA-adsorbed aluminum phosphate before and after subjected to TFFD and reconstitution are shown in Fig. 5A, and the particle size distribution profiles of the OVA-adsorbed Alhydrogel® before and after subjected to TFFD and reconstitution are shown in Fig. 5B. It is concluded that TFFD can be used to convert vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum phosphate or with the commercially available Alhydrogel® into dry powder without causing significant aggregation.

Fig. 5. TFFD of OVA adjuvanted with aluminum phosphate or Alhydrogel®.

Shown are representative particle size distribution curves of OVA-adsorbed aluminum phosphate (A) and OVA-adsorbed Alhydrogel® (B) before and after they were subjected to TFFD and reconstitution.

3.6. Thin-film freeze-drying of a commercial veterinary tetanus toxoid vaccine, a human hepatitis B vaccine, and a human papillomavirus vaccine

In order to further validate the applicability of the TFFD in drying vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts, the tetanus toxoid concentrated, adjuvanted detoxified toxin, a veterinary TT vaccine, Engerix-B, a human hepatitis B vaccine, and Gardasil, a human papillomavirus vaccine, were subjected to TFFD.

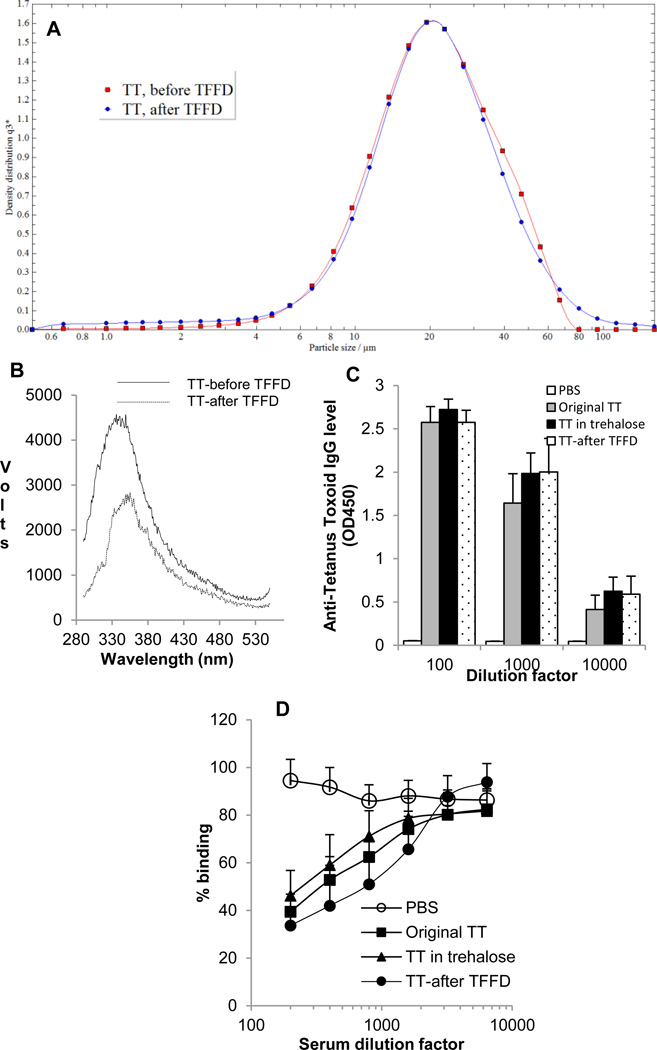

The TT vaccine was diluted, and trehalose was added to a final concentration of 2% (w/v) before the vaccine was subjected to TFFD. The particle size distribution profiles of the TT vaccine before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution are shown in Fig. 6A. The mean diameter of the particles in the original vaccine was 23.1 ± 2.1 µm, and the mean particle size the TT vaccine reconstituted from the TFFD powder was 18.4 ± 0.2 µm. Clearly, subjecting the TT vaccine to TFFD and reconstitution did not cause significant aggregation. Preliminary data also showed that subjected undiluted TT vaccine in the presence of 2% (w/v) of trehalose to TFFD and reconstitution did not cause particle aggregation as well (Thakkar & Cui, unpublished data).

Fig. 6. TFFD of tetanus toxoid vaccine.

(A). Representative particle size distribution curves of TT vaccine before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution.

(B). Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectra of TT vaccine before and after TFFD and reconstitution.

(C). Anti-tetanus toxin IgG levels in serum samples of mice immunized with TT vaccine before and after TFFD and reconstitution.

(D). Inhibition of the binding of tetanus toxoid (to polyclonal horse anti-tetanus antiserum by the antisera from immunized mice). Female BALB/c mice (n = 5) were s.c. injected with TT vaccine, before or after TFFD and reconstitution, on days 0, 14 and 28. Sterile PBS and original TT vaccine diluted in sterile PBS (original TT) or 2% trehalose (TT in trehalose) were used as controls. Mice were bled 16 days after the third dose.

To investigate whether the TFFD process significantly altered the structure of the tetanus toxoid protein, the intrinsic fluorescence spectra of the TT vaccine before and after it was subjected to TFFD were acquired and compared. As shown in Fig. 6B, the fluorescence spectrum of the TT vaccine after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution only shifted slightly right (about 20 nm) when compared to the freshly diluted TT vaccine. In addition, the fluorescence intensity of the TT vaccine following TFFD and reconstitution was also relatively lower. Freeze-drying is known to perturb the structure of proteins at any stage of the process, including freezing, drying, and reconstitution [14, 34, 35]. The TFFD may have slightly altered the structure of the detoxified tetanus toxoid. However, it is unclear how the TFFD increased the polarity of the environment surrounding the tryptophan residues in the detoxified tetanus toxoid to induce a slight right shift in the spectra. When the immunogenicity of the TT vaccine before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution was evaluated and compared in a mouse model, the anti-tetanus toxin IgG levels determined using toxoid-ELISA in all the immunized groups were not significantly different (Fig. 6C). For anti-TT antibody responses, specific IgG levels measured using the toxoid-ELISA do not correlate well with tetanus toxin-neutralizing activity determined using in vivo toxin neutralization assay in mice or guinea pigs [25]. However, it was shown that the ToBI-test is a reliable and precise alternative to the in vivo toxin neutralization assay, and there is a high degree of correlation between the ToBI-test and in vivo toxin neutralization assay [25]. Therefore, the sera from mice immunized with the TT vaccine before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution were evaluated using the ToBI-test and compared. As shown in Fig. 6D, subjecting the TT vaccine to TFFD and reconstitution did not significantly affect the ToBI-test results. Although an in vivo toxin neutralization assay may ultimately have to be carried out to assess the effect of the TFFD on the toxin-neutralizing activity of the antiserum induced by the vaccine, data in Figs. 6C–D are strongly indicative that the immunogenicity of the TT vaccine was not significantly decreased after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution.

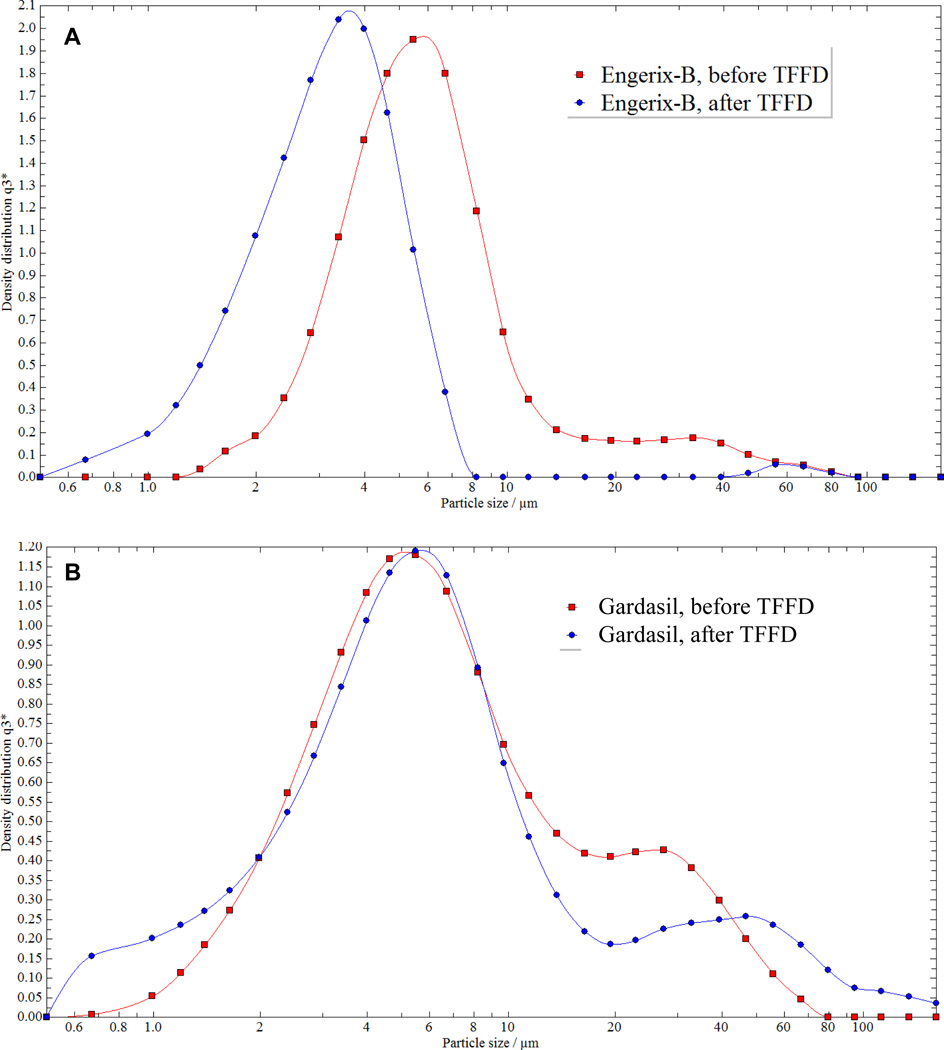

Engerix-B vaccine is a human hepatitis B vaccine, which contains human HBsAg adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (HBsAg to aluminum ratio, 1:25, w/w). To further test the applicability of the TFFD process in drying commercially available vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts, trehalose powder was added directly into the Engerix-B vaccine to a final concentration of 2% (w/v) without further dilution, and the formulation was then subjected to TFFD. Shown in Fig. 7A are representative particle size distribution profiles of the Engerix-B vaccine before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution. The particle size of the Engerix-B after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution was 3.29 ± 0.15 µm, and particle size of the fresh Engerix-B vaccine was 5.64 ± 0.01 µm. Gardasil is a human papillomavirus quadrivalent vaccine that contains L1 proteins from HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 adjuvanted with amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate (total L1 proteins to aluminum ratio, 1:1.875, w/w). It was diluted 10-fold (with a final trehalose concentration of 2% (w/v)) and then subjected to TFFD. Shown in Fig. 7B are representative particle size distribution curves of the Gardasil before and after it was subjected to TFFD and reconstitution. Clearly, subjecting human Engerix-B vaccine or Gardasil vaccine to TFFD and reconstitution did not cause any significant aggregation. Therefore, it is likely that the TFFD method can be used as a platform technology to convert vaccines that contain aluminum salts into dry powder.

Fig. 7. TFFD of Engerix-B and Gardasil.

Shown are representative particle size distribution curves of Engerix-B (A) or Gardasil (B) before and after they were subjected to TFFD and reconstitution. Engerix-B was subjected to TFFD in 2% of trehalose without further dilution. Gardasil was diluted 10-fold and then subjected to TFFD in 2% of trehalose.

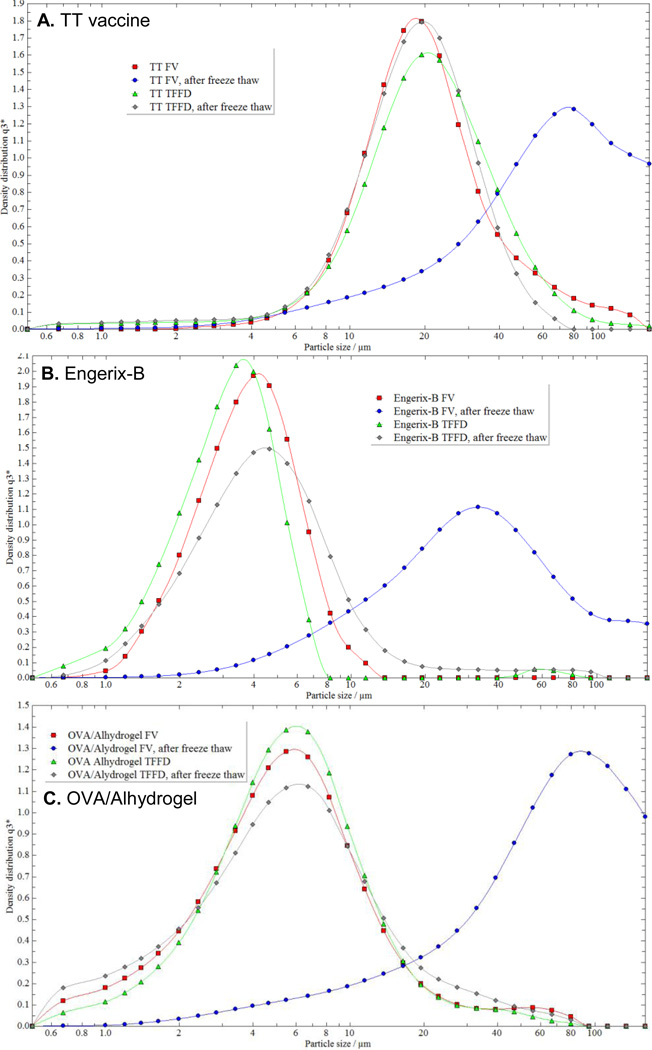

3.7. Stability of vaccine dry powder after repeated freezing-and-thawing

To test whether vaccines that are converted to dry powder using TFFD are still sensitive to inadvertent freezing (and thawing), dried powders of TT vaccine, Engerix-B vaccine, and OVA-adjuvanted Alhydrogel® (OVA/Alhydrogel®) were subjected to three cycles of freezing-and-thawing and then reconstituted. As controls, fresh vaccines that were not subjected to TFFD were also subjected to the same freezing-and-thawing cycles. As shown in Fig. 8, repeated freezing-and-thawing of all three vaccines in liquid suspension caused significant aggregations, whereas subjecting the dried powders of the same vaccines to the same freezing-and-thawing cycles did not cause any significant aggregation. Unlike liquid vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts, the same vaccines that are converted to dry powders using the TFFD are no longer sensitive to freezing conditions. Therefore, converting a vaccine that contains an aluminum salt as adjuvant from liquid to dry powder using TFFD is expected to help avoid the loss of vaccines resulted from unintentionally exposing the vaccine to freezing temperatures during transport or storage [5, 6]. Experiments to evaluate and compare the immune responses induced by thin-film freeze-dried vaccine powder before and after the powder is subjected to multiple cycles of freezing-and-thawing and then reconstitution are currently under way.

Fig. 8. Freezing-and-thawing of vaccine dry powder.

Shown are representative particle size distribution curves of TT vaccine (A), Engerix-B (B), and OVA adjuvanted with Alhydrogel® (OVA/Alhydrogel) (C), before and after the thin-film freeze-dried powders were subjected to 3 cycles of freezing-and-thawing and then reconstitution (i.e., TFFD vs. TFFD, after freeze-thaw). As controls, the particle size distribution curve of the respective fresh vaccines (i.e., FV) and the fresh vaccines after subjected to 3 cycles of freezing-and-thawing (i.e., FV, after freeze-thaw) are also included.

Various methods, including spray drying [10], spray freeze-drying [10, 14–16], and standard tray freeze-drying, have been tested to convert vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts from liquid suspension to dry powder[14–16, 36]. However, data in the literature do not show that those methods truly preserved the particle size and the immunogenicity of the vaccines [10, 14–16]. They are rather methods of preparing immunologically-active aluminum salt-adjuvanted dry vaccines, albeit with increased particle size and/or reduced immunogenicity [16]. The thin-film freeze-drying method used in the present study represents a method that converts vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts from a liquid suspension to a dry powder without causing particle aggregation or damage to the immunogenicity of the vaccines. In TFF process, liquid droplets fall from a given height above a cryogenically cooled metal surface [17]. Upon impact, the droplets spread out into thin films of 100–400 µm that froze on a time scale of 70–1,000 ms, which corresponding to a cooling rate of about 100 K/s [17, 37–42]. The rapid cooling/freezing explains why the particle size (distribution) and the immunogenicity of vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts were not significantly changed after they are subjected to TFFD and reconstitution, as it was reported that fast freezing can minimize particle coagulation and thus maximizing the immunogenicity of vaccines adjuvanted with aluminum salts [10, 15, 16]. However, in the previously reported spray freeze-drying method, when atomized vaccine droplets were dropped above liquid nitrogen, they traveled through the cold gas above the cryogenic liquid nitrogen and completely froze at an estimated cooling rate of about 106 K/s after contacting the liquid nitrogen [43]. In other words, the cooling rate during spray freezing is in theory much higher than during the TFF process. It is thus surprising that in previous reports, aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines after subjected to spray freeze-drying and reconstitution did not maintain their particle size and/or immunogenicity [10, 14–16].

Besides cooling rate, low aluminum salt concentration and high excipient levels are also indicated as two important parameters that help minimize vaccine aggregation and maximize the immunogenicity of vaccines during spray freeze-drying [10, 15]. In the present study, the concentrations of the aluminum hydroxide in the vaccine formulations we prepared ranged from 0.09% to ~1% (w/v). The concentration of aluminum in the Engerix-B was ~0.5 mg/ml, 0.045 mg/ml in the diluted Gardasil (the concentration of aluminum in the TT vaccine is unknown). It was found that trehalose as a single excipient at 2% (w/v) was sufficient to help maintain the particle size (distribution) and immunogenicity of those vaccines during the TFFD and reconstitution processes. In previous spray freeze-drying studies, the aluminum hydroxide concentration was 0.2% (w/v) [14–16] or 0.6% (w/v) [10]. Aluminum hydroxide at a final concentration of 3% (w/v) was also tested, but the immunogenicity of the resultant powder after reconstitution was significantly decreased (i.e., 10-fold weaker than that of the original liquid vaccine) [10]. The concentration of trehalose as a single excipient was 7.5% (w/v) or above [14– 16], and in Maa et al.’s study, the excipient was comprised of mannitol, dextran, and glycine [10]. Yet, the particle size and/or immunogenicity of the vaccines changed after they were subjected to spray freeze-drying and reconstitution [10, 14–16].

Therefore, it is true that fast cooling rates, low aluminum salt concentrations, and high excipient levels are critical factors/parameters in minimizing vaccine aggregation and maximizing the immunogenicity of vaccines during freeze-drying. However, other factor(s) may also play an important role in maintaining the particle size and immunogenicity of aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines during freeze-drying and reconstitution. For example, the antigens used in the freeze-drying process may be critical. Lysozyme, alkaline phosphatase, BoNT/E, BoNT/C, and HBsAg were used previously in spray freeze-drying studies [10, 14–16]. In the present study, OVA and tetanus toxoid (in a veterinary TT vaccine) were used predominately. HBsAg is the antigen in the Engerix-B vaccine, and L1 proteins of multiple HPV strains are the antigens in Gardasil, although the immunogenicity of the Engerix-B and Gardasil after subjected to TFFD and reconstitution was not tested yet. More importantly, however, it is known that during spray freeze-drying, the large gas-liquid interface in the spraying step causes protein aggregations [43–45]. The TFF process freezes liquid droplets that are dropped on the cryogenically cooled metal surface in relatively lower cooling rates, but the much smaller area of the air-liquid interface of the falling droplets and the spread film, in comparison to the atomized droplets in spray freeze-drying [17], may have contributed to the ability of the TFFD process to convert liquid aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccine to dried powder without causing significant change in the particle size and immunogenicity of the vaccines.

4. Conclusion

Vaccines that are adjuvanted with aluminum salts can be successfully converted from liquid suspension into dry powder by thin-film freeze-drying using a relatively low concentration of trehalose (2%, w/v) as an excipient, without causing particle aggregation or decrease in the immunogenicity of the vaccines. In addition, the dry vaccine powder did not aggregate after repeated freezing-and-thawing. It is expected that this thin-film freeze-drying method can be used to formulate new vaccines, or to reformulate existing vaccines, that are adjuvanted with aluminum salts into dry vaccine powder.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant (Al105789 to ZC) and a University of Texas Transform Seed Fund (to ZC and ROW). The authors would like to thank Dr. Hugh Smyth at the UT-Austin for kindly allowing us to use the Sympatec Helos laser diffraction instrument available in his lab.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hem SL, Hogenesch H. Relationship between physical and chemical properties of aluminum-containing adjuvants and immunopotentiation. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2007;6:685–698. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero Mendez IZ, Shi Y, HogenEsch H, Hem SL. Potentiation of the immune response to non-adsorbed antigens by aluminum-containing adjuvants. Vaccine. 2007;25:825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm093830.htm.

- 4.Kristensen D, Chen D, Cummings R. Vaccine stabilization: research, commercialization, and potential impact. Vaccine. 2011;29:7122–7124. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthias DM, Robertson J, Garrison MM, Newland S, Nelson C. Freezing temperatures in the vaccine cold chain: a systematic literature review. Vaccine. 2007;25:3980–3986. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lydon P, Zipursky S, Tevi-Benissan C, Djingarey MH, Gbedonou P, Youssouf BO, Zaffran M. Economic benefits of keeping vaccines at ambient temperature during mass vaccination: the case of meningitis A vaccine in Chad. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014;92:86–92. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.123471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapata MI, Feldkamp JR, Peck GE, White JL, Hem SL. Mechanism of freeze-thaw instability of aluminum hydroxycarbonate and magnesium hydroxide gels. J. Pharm. Sci. 1984;73:3–8. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600730103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisal S, Wawde G, Salvankar S, Lade S, Kadam S. Vacuum foam drying for preservation of LaSota virus: effect of additives. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2006;7:60. doi: 10.1208/pt070360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen D, Kapre S, Goel A, Suresh K, Beri S, Hickling J, Jensen J, Lal M, Preaud JM, Laforce M, Kristensen D. Thermostable formulations of a hepatitis B vaccine and a meningitis A polysaccharide conjugate vaccine produced by a spray drying method. Vaccine. 2010;28:5093–5099. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maa YF, Zhao L, Payne LG, Chen D. Stabilization of alum-adjuvanted vaccine dry powder formulations: mechanism and application. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003;92:319–332. doi: 10.1002/jps.10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Z, Johnston KP, Williams RO., 3rd Spray freezing into liquid versus spray-freeze drying: influence of atomization on protein aggregation and biological activity. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;27:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D, Kristensen D. Opportunities and challenges of developing thermostable vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2009;8:547–557. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overhoff KA, Johnston KP, Tam J, Engstrom J, Willams RO., III Use of thin film freezing to enable drug delivery; a review. J Drug Del. Sci. Tech. 2009;19:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clausi AL, Morin A, Carpenter JF, Randolph TW. Influence of protein conformation and adjuvant aggregation on the effectiveness of aluminum hydroxide adjuvant in a model alkaline phosphatase vaccine. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009;98:114–121. doi: 10.1002/jps.21433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clausi A, Cummiskey J, Merkley S, Carpenter JF, Braun LJ, Randolph TW. Influence of particle size and antigen binding on effectiveness of aluminum salt adjuvants in a model lysozyme vaccine. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008;97:5252–5262. doi: 10.1002/jps.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randolph TW, Clausi A, Carpenter JF, Schwartz DK. In: Method of preparing an immunologically-active adjuvant-bound dried vaccine composition. W.I.P. Organization, editor. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engstrom JD, Lai ES, Ludher BS, Chen B, Milner TE, Williams RO, 3rd, Kitto GB, Johnston KP. Formation of stable submicron protein particles by thin film freezing. Pharm. Res. 2008;25:1334–1346. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang M, Li H, Lang B, O'Donnell K, Zhang H, Wang Z, Dong Y, Wu C, Williams RO., 3rd Formulation and delivery of improved amorphous fenofibrate solid dispersions prepared by thin film freezing. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012;82:534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watts AB, Wang YB, Johnston KP, Williams RO., 3rd Respirable low-density microparticles formed in situ from aerosolized brittle matrices. Pharm. Res. 2013;30:813–825. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0922-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Aldayel AM, Cui Z. Aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles show a stronger vaccine adjuvant activity than traditional aluminum hydroxide microparticles. J. Control. Release. 2014;173:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinella JV, Jr, White JL, Hem SL. Treatment of aluminium hydroxide adjuvant to optimize the adsorption of basic proteins. Vaccine. 1996;14:298–300. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leach WT, Simpson DT, Val TN, Anuta EC, Yu Z, Williams RO, 3rd, Johnston KP. Uniform encapsulation of stable protein nanoparticles produced by spray freezing for the reduction of burst release. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005;94:56–69. doi: 10.1002/jps.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang G, Joshi SB, Peek LJ, Brandau DT, Huang J, Ferriter MS, Woodley WD, Ford BM, Mar KD, Mikszta JA, Hwang CR, Ulrich R, Harvey NG, Middaugh CR, Sullivan VJ. Anthrax vaccine powder formulations for nasal mucosal delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;95:80–96. doi: 10.1002/jps.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloat BR, Sandoval MA, Hau AM, He Y, Cui Z. Strong antibody responses induced by protein antigens conjugated onto the surface of lecithin-based nanoparticles. J. Control. Release. 2010;141:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendriksen CF, vd Gun JW, Nagel J, Kreeftenberg JG. The toxin binding inhibition test as a reliable in vitro alternative to the toxin neutralization test in mice for the estimation of tetanus antitoxin in human sera. J. Biol. Stand. 1988;16:287–297. doi: 10.1016/0092-1157(88)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coombes L, Tierney R, Rigsby P, Sesardic D, Stickings P. In vitro antigen ELISA for quality control of tetanus vaccines. Biologicals. 2012;40:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendriksen CF, van der Gun JW, Marsman FR, Kreeftenberg JG. The use of the in vitro toxin binding inhibition (ToBI) test for the estimation of the potency of tetanus toxoid. Biologicals. 1991;19:23–29. doi: 10.1016/1045-1056(91)90020-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clausi AL, Merkley SA, Carpenter JF, Randolph TW. Inhibition of aggregation of aluminum hydroxide adjuvant during freezing and drying. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008;97:2049–2061. doi: 10.1002/jps.21143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff L, Flemming J, Schnitz R, Groger K, Muller-Goymann C. Protection of aluminum hydroxide during lyophilization as an adjuvant for freeze-dried vaccines. Colloid. Surface. 2008;330:116–126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W. Lyophilization and development of solid protein pharmaceuticals. Int. J. Pharm. 2000;203:1–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith ERB. The effect of variations in ionic strength on the apparent isoelectric point of egg albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1935;108:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crowe LM, Reid DS, Crowe JH. Is trehalose special for preserving dry biomaterials? Biophys. J. 1996;71:2087–2093. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79407-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buitink J, Van den Dris IJ, Hoekstra FA, Alberda M, Hemminga MA. High critical temperature above Tg may contribute to the stability of biological systems. Biophys. J. 2000;79:1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76365-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arakawa T, Prestrelski SJ, Kenney WC, Carpenter JF. Factors affecting short-term and long-term stabilities of proteins. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2001;46:307–326. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter JF, Pikal MJ, Chang BS, Randolph TW. Rational design of stable lyophilized protein formulations: some practical advice. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:969–975. doi: 10.1023/a:1012180707283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassett KJ, Cousins MC, Rabia LA, Chadwick CM, O'Hara JM, Nandi P, Brey RN, Mantis NJ, Carpenter JF, Randolph TW. Stabilization of a recombinant ricin toxin A subunit vaccine through lyophilization. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;85:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukai J, Ozaki T, Asami H, Miyatake O. Numerical Simulation of Liquid Droplet Solidification on Substrates. J. Chem. Eng. Japan. 2000;33:630–637. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett T, Poulikakos D. Splat-quench solidification: estimating the maximum spreading of a droplet impacting a solid surface. J. Mater. Sci. 1993;28:963–970. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Wang XY, Zheng LL, Jiang XY. Studies of splat morphology and rapid solidification during thermal spraying. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2001;44:4579–4592. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasandideh-Fard M, Bhola R, Chandra S, Mostaghimi J. Deposition of tin droplets on a steel plate: simulations and experiments. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 1998;41:2929–2945. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasandideh-Fard M, Chandra S, Mostaghimi J. A three-dimensional model of droplet impact and solidification. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2002;45:2229–2242. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madejski J. Solidification of droplets on a cold surface. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 1976;19:1009–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang ZH, Baust JG. Ultra-rapid freezing by spraying/plunging: pre-cooling in the cold gaseous layer. J. Microsc. 1991;161:435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1991.tb03101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb SD, Golledge SL, Cleland JL, Carpenter JF, Randolph TW. Surface adsorption of recombinant human interferon-gamma in lyophilized and spray-lyophilized formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002;91:1474–1487. doi: 10.1002/jps.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engstrom JD, Simpson DT, Cloonan C, Lai ES, Williams RO, 3rd, Barrie Kitto G, Johnston KP. Stable high surface area lactate dehydrogenase particles produced by spray freezing into liquid nitrogen. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007;65:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]