Abstract

Changes in histone post-translational modifications are associated with epigenetic states that define distinct patterns of gene expression. It remains unclear whether epigenetic information can be transmitted through histone modifications independently of specific DNA sequence, DNA methylation, or RNAi. Here we show that, in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, ectopically induced domains of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me), a conserved marker of heterochromatin, are inherited through several mitotic and meiotic cell divisions after removal of the sequence-specific initiator. The putative JmjC domain H3K9 demethylase, Epel, and the chromodomain of the H3K9 methyltransferase, Clr4/Suv39h play opposing roles in maintaining silent H3K9me domains. These results demonstrate how a direct ‘read-write’ mechanism involving Clr4 propagates histone modifications and allows histones to act as carriers of epigenetic information.

An individual cell can give rise to progeny with distinct patterns of gene expression and phenotypes without change in its DNA sequence. In eukaryotic cells, a major mechanism that gives rise to such phenotypic or epigenetic states involves changes in histone post-translational modifications and chromatin structure (1, 2). The basic unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which is composed of 147 bp of DNA wrapped twice around an octamer composed of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (3). The highly conserved basic amino termini, and to a lesser extent the globular domains, of histones contain a variety of post-translational modifications that affect nucleosome stability or provide binding sites for effectors that activate or repress transcription (4–8).

It has been known for nearly four decades that during DNA replication parental histones are retained and randomly distributed to newly synthesized daughter DNA strands (9–12). It was therefore logical to propose that combinations of histone modifications, sometimes referred to as a “histone code,” are responsible for epigenetic memory of gene expression patterns (13, 14). However, previous attempts to separate sequence-specific establishment from maintenance have failed to provide unambiguous support for a purely histone-based inheritance mechanism in systems that display stable epigenetic expression states (2, 15, 16). Most notably, silencers, DNA sequences that mediate the establishment of hypoacetylated domains of silent chromatin in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, are continuously required for maintenance of the silent state (17,18). Similarly, the Drosophila Polycomb Response Element (PRE), which acts analogously to the yeast silencer, is continuously required for maintenance of domains of H3K27 methylation and reporter gene silencing (19, 20). The question therefore remains as to whether histones can act as carriers of epigenetic information in the absence of any input from the underlying DNA sequence.

The fission yeast Schizosac-charomyces pombe contains extensive domains of heterochromatin at its pericen-tromeric DNA repeats, subtelo-meric regions, and the silent mating type loci (21). These domains share many features of heterochromatin in multicellular eukaryotes such as H3K9 methylation, which is catalyzed by the human Suv39h homolog Clr4, association with HP1 proteins (Swi6 and Chp2), and histone hypoacetylation. Furthermore, S. pombe heterochromatin displays epigenetic inheritance properties in which cells containing a reporter gene inserted within heterochromatin display variegating reporter gene expression (22). The ON and OFF states of such reporter genes can be stably transmitted in cis through both mitotic and meiotic cell divisions (23, 24). However, since these observations of epigenetic inheritance were made at native sequences, contributions arising from sequence specific elements that stabilize heterochromatin could not be ruled out (2). To determine whether heterochromatin maintenance can be separated from the sequences that initiate its establishment, we developed a system for inducible heterochromatin establishment in S. pombe by fusion of the Clr4 methyltransferase catalytic domain to the bacterial tetracycline repressor (TetR) protein. This allowed us to establish an extended heterochromatic domain and study its initiator-independent maintenance by either tetracycline-mediated release of TetR-Clr4 from DNA or after deletion of the TetR module. Our results indicate that domains of H3K9 methylation can be inherited for >50 generations in the absence of sequence specific recruitment, and define central roles for the putative demethylase, Epel in the erasure of H3K9 methylation and the chromodomain of the Clr4 methyltransferase in its maintenance.

Inducible establishment of heterochromatin

Silent chromatin domains can be established by ectopic recruitment of histone modifying enzymes to chromatin via fusion with heterologous DNA-binding proteins (25, 26). In order to create an inducible system for heterochromatin formation, we fused a Clr4 protein lacking its amino terminal chromodomain (required for binding to methylated his-tone H3K9) while retaining its enzymatic methyltransferase activity to the bacterial TetR protein (designated TetR-Clr4-I for TetR-Clr4-Initiator) (Fig. 1A). The TetR DNA binding domain facilitates protein targeting to a locus that harbors its cognate DNA binding sequence and this recruitment activity is abrogated by the addition of tetracycline (TetRoff system) (27). We generated cells in which TetR-Clr4-I replaced the wild type Clr4 (TetR-clr4-I) or cells in which wild type Clr4 was intact and TetR-Clr4-I was inserted at another locus (TetR-clr4-T, clr4+). Comparisons between strains with or without clr4+ allowed us to evaluate the contribution of the Clr4 chromodomain to establishment and/or maintenance. To generate a reporter locus, we replaced the eu-chromatic ura4+ locus with an ade6+ gene containing 10 tetracycline operators immediately upstream of the promoter (10XtetO-ade6+) (Fig. 1A). ade6+ provides a convenient visual reporter as its silencing results in formation of red or pink colonies upon growth on medium with limiting adenine concentrations (22).

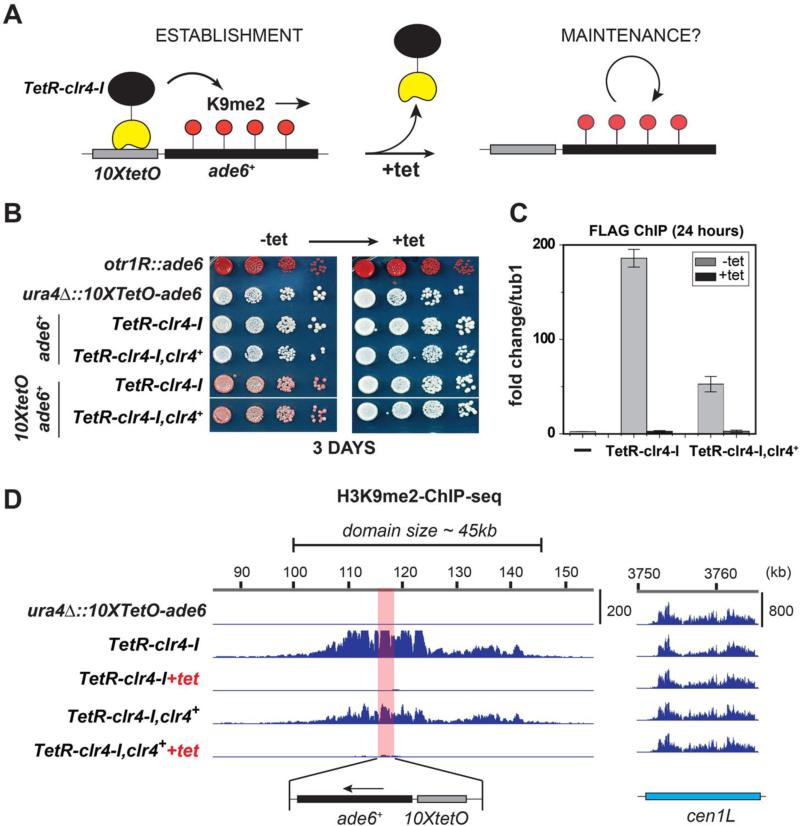

Fig. 1. Ectopic heterochromatin is lost after sequence-specific establishment upon tetracycline addition.

(A) Diagram of experimental scheme for TetR-Clr4-lnitiator (TetR-Clr4-l)-mediated H3K9 methylation at the ura4Δ::10XtetO-ade6+ locus. Tetracycline (tet) promotes the release of TetR-Clr4-l from tetO sites so that initiator-independent maintenance could be tested. (B) Test of ade6+ silencing on low-adenine medium in the absence (-tet) and presence (+tet) of tetracycline. Silencing of ade6+ results in formation of red colonies. Centromeric ade6+ (otrlR::ade6), the target locus alone (ura4Δ::10XtetO-ade6+), and ura4Δ::ade6+ cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChlP)-qPCR experiments assess the association of FLAG-tagged TetR-Clr4-l with the 10XtetO-ade6+ locus in the presence and absence of tetracycline. (−) indicates background ChIP signal from cells that did not express TetR-Clr4-l. In the presence of tetracycline, TetR-Clr4-l occupancy is close to background levels. (D) ChlP-seq experiments show that TetR-Clr4-l induces a de novo H3K9me2 domain that surrounds the tetO-ade6+ locus (highlighted in red) for ~20 kb on either side, in cells with or without c/r4+, which is lost 24 hours after tetracycline addition. H3K9me2 ChlP-qPCR data and H3K9me3 for samples in (D) are presented in fig. SI. Chromosome 3 (site of insertion of 10XtetO-ade6+) and chromosome 1 (centromere 1 left, cen1L) coordinates are shown above the tracks and read numbers (per million) are indicated on the right. H3K9me2 at DNA repeats of cen1L serves as an internal control for the ChlP-seq data.

As shown in Fig. 1B, cells containing the 10XtetO-ade6+ reporter in combination with the expression of the TetR-Clr4-I fusion protein, but not those containing the fusion protein alone or the reporter alone, formed pink colonies on low-adenine medium lacking tetracycline (-tet). Consistent with previous observations (26), silencing did not require clr4+, suggesting that the chromodomain of Clr4 was not required for de novo heterochromatin establishment (Fig. 1B), but depended on HP1 proteins (Swi6 and Chp2) and histone deacetylases (Clr3 and Sir2), which act downstream of H3K9 methylation (fig. S1A). Colonies grown in the absence of tetracycline were then plated on medium containing tetracycline (+tet) to determine whether the silent state could be maintained upon release of TetR-Clr4-I from DNA. Tetracycline-dependent release of TetR-Clr4-I from tetO sites resulted in loss of silencing as indicated by formation of white colonies (Fig. 1B, +tet). Chromatin immunoprecipi-tation (ChIP) experiments verified that tetracycline addition resulted in release of TetR-Clr4-I from the 10XtetO sites, as the TetR ChIP signal in the presence of tetracycline was near background levels similar to that observed for cells which lack TetR-Clr4-I (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, ChIP combined with high throughput sequencing (ChlP-seq) and ChlP-qPCR experiments showed that a 40 to 50 kb domain of H3K9 di- and tri-methylation (H3K9me2 and me3) encompassing the 10XtetO-ade6+ region was completely lost 24 hours (~10 cell divisions) after the addition of tetracycline to the growth medium (Fig. 1D and fig. SI, B to D). We obtained similar results with cells that carried a wild type copy of clr4+ in addition to TetR-clr4-I (Fig. 1D and fig. SID, lower 2 rows). These results demonstrate that a domain of H3K9 methylation and the associated silent state are reversed within 10 cell divisions after release of the sequence-specific initiator from DNA.

Inheritance uncoupled from sequence specific initiation

A minimal mechanistic requirement for inheritance of a domain containing H3K9me marks involves the recognition of pre-existing H3K9 methylated histones coupled to the modification of newly deposited histones. The loss of a ~45kb domain of H3K9 di-methylation after release of TetR-Clr4-I (Fig. 1D) may either be due to nucleosome exchange processes associated with transcription and chromatin remodeling or erasure of the methyl mark by a demethylase. Alternatively, the rapid decay of methylation in this domain may be facilitated by competition between the ectopic locus and native heterochromatic domains for a limiting pool of proteins that play critical roles in maintenance.

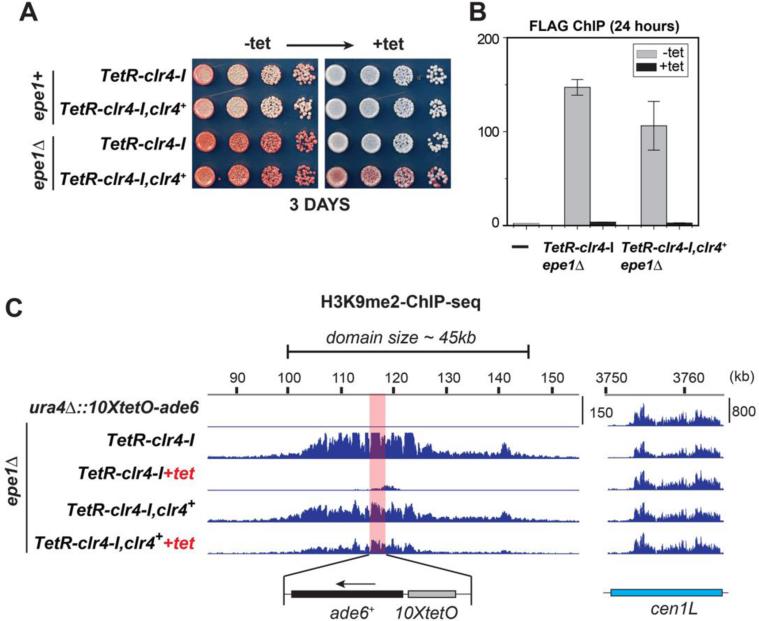

In order to test these different scenarios, we constructed TetR-clr4-I, 10XtetO-ade6+ cells (with or without clr4+) that carried deletions for genes involved in various chromatin maintenance pathways (28–30). The deletion of epe1+, which encodes a putative histone H3K9 demethylase (30), did not affect the establishment of silencing as indicated by the appearance of red colonies on -tet medium for both TetR-clr4-I, epe1Δ cells and TetR-clr4-I, clr4+, epe1Δ cells (Fig. 2A, left side). In contrast to epe1+ cells, epelΔ cells formed red, white, and sectored colonies in the presence of tetracycline indicating that the silent state was maintained after release of the initiator and this phenotype was observed only in the case of cells which also contained a wild type copy of clr4+ (Fig. 2A, right side, compare last 2 rows with first 2 rows). ChIP experiments verified that tetracycline addition promoted the release of TetR-Clr4-I from tetO sites (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the colony color silencing assays, ChlP-seq and ChlP-qPCR experiments also indicated that the large domain of H3K9 di- and tri-methylation surrounding the 10XtetO-ade6+ locus was lost in TetR-clr4-I, epelΔ cells but was maintained in TetR-clr4-I, clr4+, epelΔ cells (Fig. 2C and fig. S2, A to C) 24 hours after the addition of tetracycline. Within this domain, the expression of several other transcription units was silenced on –tet medium and this silencing was maintained for several hours after tetracycline addition (fig. S3).

Fig. 2. Deletion of epel+ allows maintenance of heterochromatin after release of TetR-Clr4-l.

(A) Color silencing assays showing that in TetR-clr4-l, clr4+, epelΔ cells silencing is maintained on +tet medium. (B) ChIP experiments showing that TetR-Clr4-l is released from tetO sites in +tet medium. (C) ChlP-seq experiments showing that in epelΔ cells H3K9me2 is maintained 24 hours after tetracycline addition in a clr4+-dependent manner. H3K9me2 ChlP-qPCR and H3K9me3 ChlP-seq data for samples in (C) and (D) are presented in fig. S2. Error bars represent standard deviations. Chromosome 3 (site of insertion of 10XtetO-ade6+) and chromosome 1 (centromere 1 left, cen1L) coordinates are shown above the tracks and read numbers (per million) are indicated on the right. H3K9me2 at DNA repeats of cen1L serves as an internal control for the ChlP-seq data.

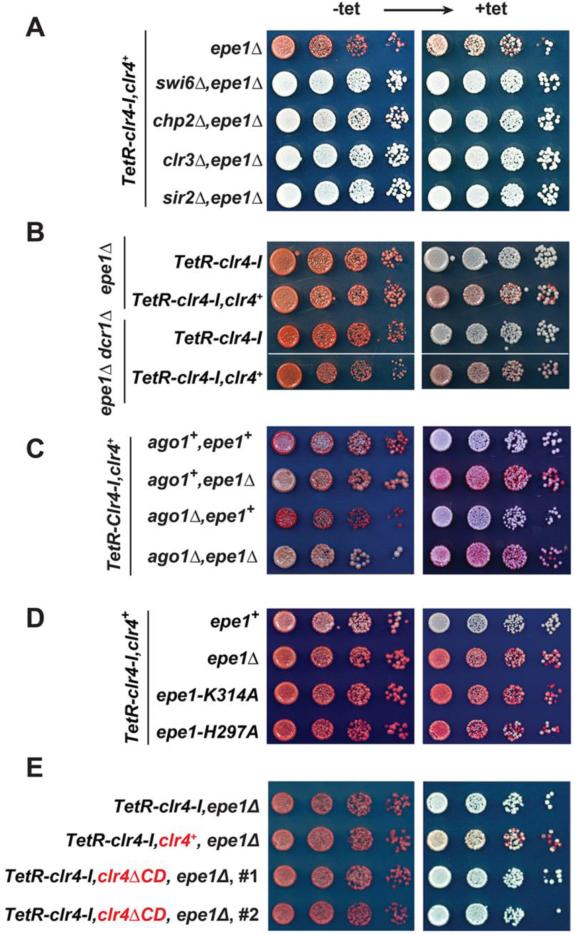

Maintenance of the silent state in epelΔ cells required the HP1 proteins (Swi6 and Chp2), and the Clr3 and Sir2 histone deacetylases (Fig. 3A) but not the Dicer ribonuclease (Dcri) or the Argonuate protein (Agol) (Fig. 3, B and C). Thus, maintenance requires the machinery that acts downstream of H3K9 methylation, but occurs independently of an RNAi-based mechanism. Consistent with the idea that Epel acts as a demethylase, the replacement of epe1+ with alleles containing active site mutations (epel-K314A and epel-H297A) (30, 31) displayed a maintenance phenotype similar to its deletion (epelΔ) (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, consistent with a requirement for the chromodomain of clr4+ in maintenance (Fig. 2A), the replacement of clr4+ with a clr4-IΔ allele (which lacks the chromodomain) resulted in the formation of only white colonies on +tet medium (Fig. 3E). Therefore, rather than differences in clr4+ dosage, the appearance of red/sectored colonies depends on the presence of Clr4 with an intact chormodomain.

Fig. 3. Requirements for maintenance of the initiator-independent silent state.

(A) Establishment and maintenance require HP1 proteins (Swi6 and Chp2) and HDACs (Clr3 and Sir2). (B) Maintenance of ectopic silencing in epelΔ cells does not require Dicer (Deri) as indicated by the growth of red, dcrlΔ cells on +tet medium. (C) Maintenance of ectopic silencing in epelΔ cells does not require Argonaute (Agol) as indicated by the growth of red, agolΔ cells on +tet medium. (D) Either deleting epel (epelΔ) or mutations in its active site (epel-K314A or epel-H297A) allow maintenance of the off state after release of the TetR-Clr4-I initiator. (E) Replacement of clr4+ with clr4ΔCD, encoding Clr4 lacking the chromodomain, abolishes initiator-independent silencing.

In an attempt to identify other features of chromatin that could be important for maintenance, we deleted two genes that are associated with transcription, mst2+, which encodes a histone acetyltransferase (32), and set1+, which encodes a histone H3K4 methyltransferase (33). In both cases we observed stronger than wild-type establishment (-tet) and weak maintenance (+tet) effects (fig. S4, A and D). While there were no obvious effects on colony color after 3 days of growth on tetracycline-containing medium, we observed clear persistence of H3K9 methylation coupled with the release of TerR-Clr4-I in mst2Δ cells 24 hours after addition of tetracycline (fig. S4, B and C). We then tested whether destabilizing endogenous heterochromatic regions could release factors that affect maintenance by deleting pozl+, a DNA-binding protein required for heterochromatin formation at telomeres (34), or dcrl+, which is required for RNAi-dependent heterochromatin formation at centromeres (35) (fig. S5). In these mutants, effects on colony color were absent (dcrlΔ, fig. S5A) or subtle (pozlΔ, fig. S5D), but we clearly observed persistence of H3K9 methylation after 24 hours after release of TetR-Clr4-I in both deletion backgrounds (fig. S5, B, C, E, and F).

These results indicate that a domain of H3K9 di-methylation and its associated silent state can be maintained through mitotic cell divisions in the absence of sequence-specific initiation. The decay rate of this epigenetic state is primarily influenced by the erasure of the methylation mark by the putative demethylase Epel and to a lesser extent by pathways that promote transcription or heterochromatin assembly at endogenous loci. We note that the efficiency of maintenance does not correlate with the strength of the initial silenced state (establishment) indicating that perturbations to each pathway results in the release or recruitment of subsets of proteins that make different contributions to establishment and/or maintenance of heterochromatin.

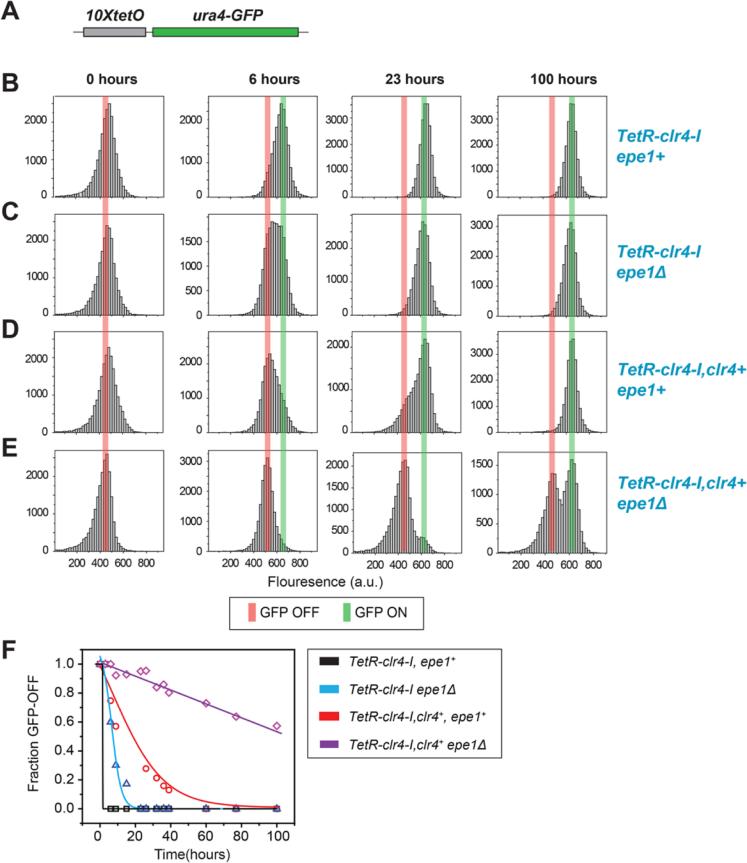

Since the different deletions essentially altered the rate of decay of ectopic H3K9 methylation, we hypothesized that epigenetic maintenance at the ectopic locus might also exist in wild type cells over the time scales of a few cell divisions. To observe the decay of silent chromatin with higher time resolution, we generated cells in which a GFP reporter was silenced by TetR-Clr4-I. We modified the endogenous ura4+ gene to encode a Ura4-GFP fusion protein. In addition, we inserted the same 10XtetO sites used in the earlier experiments immediately upstream of a 114bp fragment of the ura4+ promoter (Fig. 4A). As determined by FACS analysis, 10XtetO-ura4-GFP was silenced in a TetR-Clr4-I-dependent manner in the presence or absence of clr4+. To assess decay rates, we transferred cells that were grown in medium lacking tetracycline (GFP OFF cells), to medium containing tetracycline and harvested samples at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 23, 26, 32, 36, 39, 50, 60, 77, and 100 hours for FACS analysis. FACS data for a subset of these time points are presented in Fig. 4, B to E, and the results for all time points are plotted in Fig. 4F. In general, upon tetracycline addition, the pattern of silencing of the 10XtetO-ura4-GFP reporter in either epelΔ or epelA over the time scale of ~2 days was consistent with the 10XtetO-ade6+ silencing results (Fig. 4, B and C). With the higher time resolution and sensitivity of detecting pheno-typic expression states, we found that the OFF state persists in ~10% of the TetR-clr4-I, clr4+, epeT cells for up to 40 hours (~20 cell divisions) after transfer to tetracycline-containing medium (Fig. 4, D and F), while cells containing TetR-clr4-I, clr4+, epelΔ, displayed the most stable maintenance patterns with ~60% of the cells maintaining the OFF state even after 100 hours of growth (~50 cell divisions) in tetracycline containing medium (Fig. 4E). These observations indicate that epigenetic maintenance was not unique to epelΔ cells and that its detection was normally masked by the rapid erasure of H3K9me marks by Epe1. While the decay rate for cells containing TetR-clr4-I, epe+ was rapid (<6 hours), the deletion of Epel even in this background resulted in a slower decay rate (Fig. 4E). We observed the GFP OFF state in TetR-clr4-I, epelΔ cells lacking clr4+, 6 hours after transfer to tetracycline medium with a complete shift to the ON state occurring only at about 23 hours after transfer (Fig. 4C). In these cells, upon elimination of Epel, the decay rate is likely defined primarily by the dilution of modified histones, which may maintain epigenetic states for a few generations in the absence of Clr4-mediated re-establishment.

Fig. 4. Kinetics of decay of the silent state after release of TetR-Clr4-l using a GFP reporter gene reveals epigenetic maintenance in epel+ cells.

(A) Schematic diagram of the 10XtetO-ura4-GFP locus. (B to E) FACS analysis of GFP expression in the indicated strains at 0, 6, 23, and 100 hours after tetracycline addition shows the time evolution of the distribution of GFP-OFF cells. (F) Data for time points between 0 and 100 hours after addition of tetracycline were plotted to display the fraction of GFP-OFF cells as a function of time. Dose response curve fitting was used as a guide.

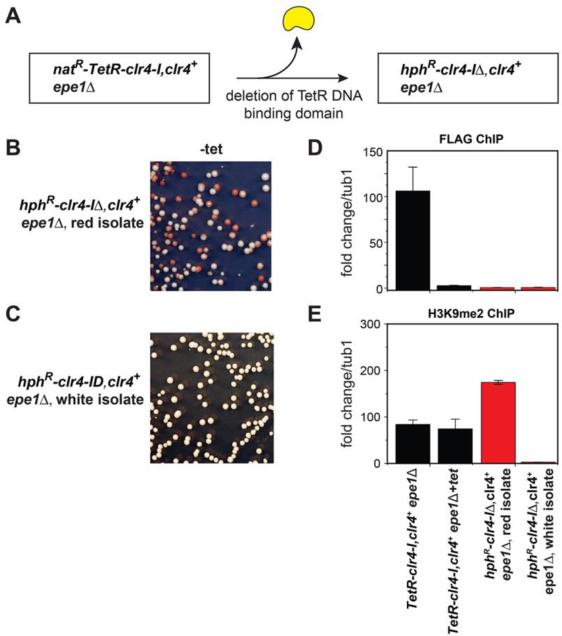

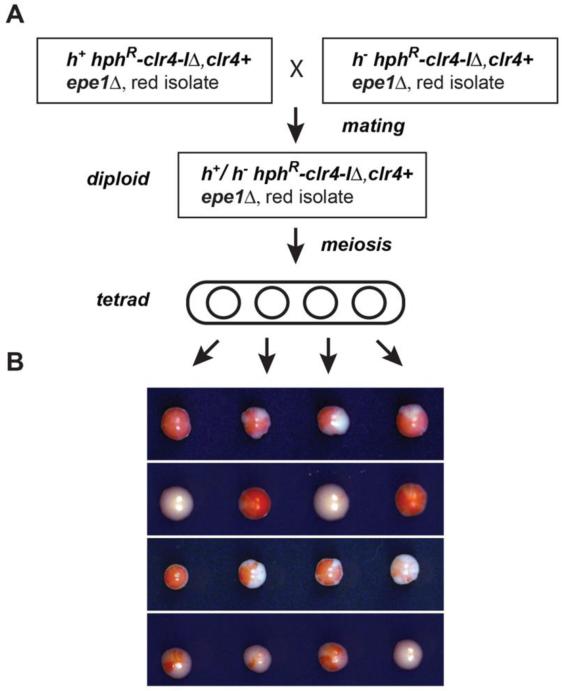

It may be argued that maintenance of H3K9 methylation and the silent state in the initiator-based experiments might arise from low affinity binding of TetR-Clr4-I to DNA in the presence of tetracycline (27). We sought to unequivocally rule out any role for sequence-specific initiation in the inheritance we observed by using homologous recombination to replace TetR-clr4-I with clr4-lΔ which harbors a deletion of the TetR DNA binding domain (Fig. 5A). Following transformation to replace TetR-clr4-T with clr4-lΔ and plating on selective low-adenine medium (Fig. 5A and Fig. 5 legend), we obtained red, sectored as well as white colonies, which were tested and confirmed for the replacement event by allele-specific PCR (fig. S6). The isolation of red clr4-lΔ, epelΔ cells confirmed that the silent state could be maintained in the complete absence of sequence-dependent Clr4 recruitment to DNA. Furthermore, the plating of red clr4-lΔ, epelΔ cells on low-adenine medium produced both red and white colonies (Fig. 5B), while plating of white clr4-lΔ, epelΔ isolates produced only white colonies (Fig. 5C). In the absence of the initiator and no other means of re-establishment, the loss of the silent state was an irreversible event (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the deletion of the TetR domain, ChIP experiments showed a complete loss of the TetR occupancy signal at the 10XtetO-ade6+ locus (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, we detected high levels of H3K9 di- methylation at the 10XtetO-ade6+ locus in red but not white isolates (Fig. 5E). We conclude that, once assembled, silent chromatin and histone H3K9 methylation at the l0XtetO-ade6+ locus can be maintained in the complete absence of the sequence-specific recruitment. To determine whether the initiator-independent silent state could also be inherited through meiosis, we crossed red haploid cells of opposite mating type, which lacked the TetR DNA binding domain (clr4-lΔ, clr4+, epelΔ), to obtain diploid cells (Fig. 6A). These diploid cells were then sporulated and following tetrad dissection, the resulting haploid progeny were plated on low-adenine medium. As shown in Fig. 6B, the resulting haploid cells formed mostly red or sectored colonies, indicating that the silent state was also inherited through meiotic cell divisions.

Fig. 5. Silencing and H3K9 methylation are maintained after deletion of the TetR DNA binding domain.

(A) Diagram showing the experimental scheme for conversion of TetR-clr4-l to clr4-IΔ, which lacks recruitment activity because it can no longer bind to tetO sites. The isolation of sectored and red clr4-IΔ cells demonstrates maintenance in the complete absence of the TetR DNA binding domain (B), while white clr4-IΔ colonies indicate irreversible loss of silencing (C). (D) ChlP-qPCR experiments show that FLAG-tagged TetR-Clr4 signal could be detected at tetO sites in clr4-IΔ cells. (E) ChlP-qPCR experiments show elevated levels of H3K9 methylation in silent clr4-IΔ cells (red isolates) but background levels of methylation in ade6+ expressing (white) clr4-IΔ cells. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Fig. 6. Inheritance of initiator-independent silencing through meiotic cell divisions.

(A) Scheme for mating of silent (red) ade6+ haploid cells of the indicated genotypes in which the TetR-Clr4l was deleted. After sporulation of the resulting diploid cells, tetrads were dissected and the haploid meiotic progeny were plated on low adenine-medium (B). Results of four tetrad dissections are presented and show inheritance and variegation of the silent state.

Inheritance of H3K9me at native heterochromatin

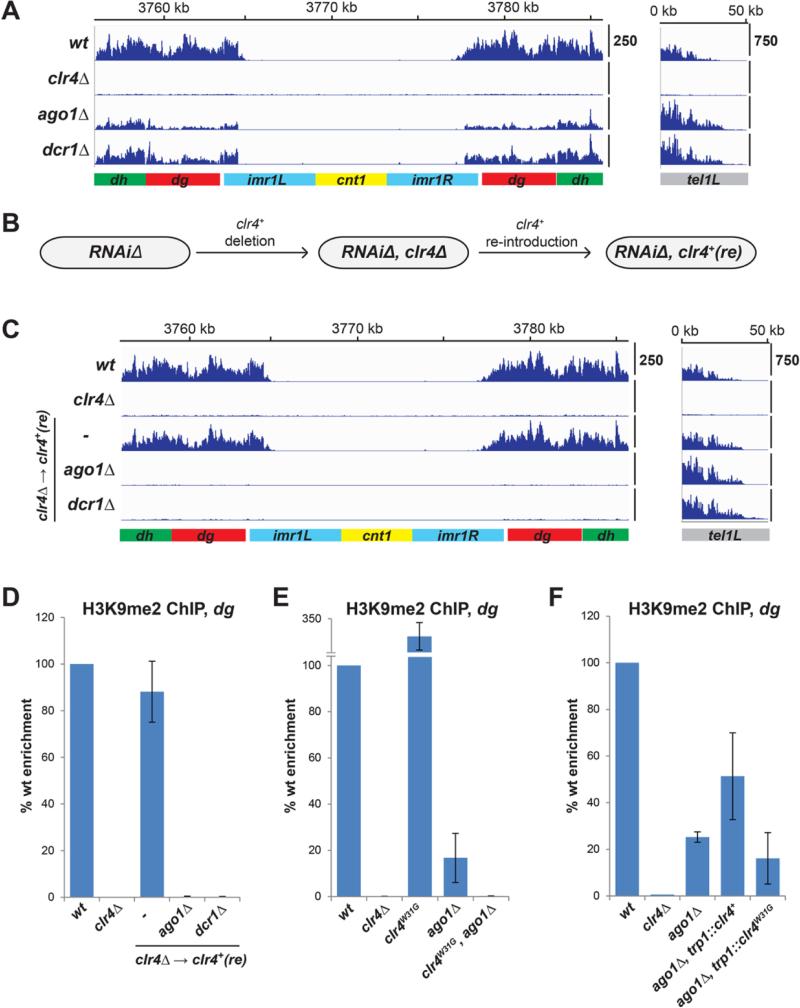

We next determined the extent to which epigenetic maintenance mechanisms akin to what is observed for the ectopic locus might also operate at native S. pombe pericentromeric repeats. Although RNAi is required for silencing of reporter genes that are inserted within pericentromeric repeat regions, deletion of RNAi components does not entirely eliminate H3K9 methylation and silencing (36, 37) (Fig. 7A). Residual H3K9 methylation in RNAi deletions might arise from either epigenetic maintenance mechanisms or weak RNAi-independent establishment signals within centromeres (38). To test for the presence of RNAi-independent signals which may operate at pericentromeric repeats, we determined whether H3K9 methylation could be established de novo at the repeats in cells with deletions of RNAi factors dcr1+ or agol+. To perform this experiment, we reintroduced clr4+ into clr4Δ, clr4Δ agolΔ, or clr4Δ dcrlΔ cells (Fig. 7B) and quantified H3K9 di-methylation levels using ChlP-seq and ChlP-qPCR. As shown in Fig. 7C, the reintroduction of clr4+ into clr4Δ cells fully restored H3K9 di-methylation at the pericentromeric dg and dh repeats of chromosome 1. In contrast, clr4+ reintroduction into clr4Δ agolΔ or clr4Δ dcrlΔ double mutant cells failed to promote any H3K9 di-methylation (Fig. 7, C and D). These results show that RNAi is the primary mechanism for sequence specific establishment of pericentromeric H3K9me domains and suggests that the H3K9me observed at these repeats after deletion of RNAi components results from epigenetic maintenance.

Fig. 7. RNAi-independent H3K9 methylation at pericentromeric repeats is epigenetically inherited.

(A) ChlP-seq experiments showing the persistence of residual histone H3K9me2 at the pericentromeric dg and dh repeats of chromosome 1 in agolΔ and dcrlΔ cells. Libraries were sequenced on the lllumina HiSeq2500 platform and normalized to read per million (y axis). Chromosome coordinates are indicated above the plots. (B) Scheme for the reintroduction of clr4+ into RNAiΔ, clr4Δ cells to test the requirement for RNAi in H3K9me establishment. clr4+ was reintroduced to the native locus to avoid overexpression. (C) ChlP-seq experiments showing that the re-introduction of clr4+ into clr4Δ cells, but not clr4Δ agolA or clr4Δ dcrlΔ cells, restores H3K9me2 at the pericentromeric repeats of chromosome 1 (left). Reads for H3K9me2 at the telomeres of chromosome 1 (telLl) on the right side show that, unlike the centromeres, establishment of telomeric H3K9me does not require RNAi. (D) ChlP-qPCR experiments verify that RNAi is required for the reestablishment of H3K9me2 at the pericentromeric dg repeats. (E) ChlP-qPCR experiments show that a mutation in the chromodomain of Clr4 (clr4W31G) abolishes the maintenance of H3K9me2 at dg repeats. (F) ChlP-qPCR experiments show that an additional copy of wild type clr4+, but not clr4W31G, boosts residual H3K9me2 levels at dg. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Our ectopic heterochromatin experiments established a role for the chromodomain of Clr4 in epigenetic inheritance of H3K9me (Figs. 2 to 5). Consistent with the hypothesis that RNAi-independent H3K9me at pericentromeric repeats is maintained by epigenetic mechanisms, residual H3K9me at the centromeric dg repeats was abolished in agolΔ clr4-W31G double mutant cells (Fig. 7E). Clr4-W31G contains a mutation in the chromodomain that attenuates binding to H3K9me (39). The complete loss of H3K9me in agolΔ clr4-W31G double mutant cells therefore suggests that the residual H3K9me marks are maintained by a mechanism that involves direct chromodomain-dependent recruitment of Clr4 to pre-existing marks. In further support of this hypothesis, the introduction of an additional copy of wild type clr4+, but not the clr4-W31G mutant, into agolΔ cells boosted the residual H3K9 methylation levels by about 3-fold (Fig. 5F). Together, these results support a direct “read-write” mechanism in which Clr4 binds to pre-existing H3K9 methylated nucleosomes and catalyzes the methylation of H3K9 on newly deposited nucleosomes to maintain heterochromatin independently of the initial signals that induced methylation. It is noteworthy that, in RNAi mutant cells, deletions of epel+, mst2+ and poz1+ boost H3K9me levels and restore silencing to varying degrees at the pericentromeric repeats (28–30). Furthermore, consistent with its role in H3K9me inheritance, the chromodomain of Clr4 is also required for the RNAi-independent spreading of H3K9me at the mating type locus (40). Our results suggest that the epigenetic maintenance of H3K9 methylation, rather than alternative establishment pathways, is primarily responsible for RNAi-independent silencing in these deletion backgrounds.

Discussion

Our findings on mitotic and meiotic inheritance of H3K9 methylation and silent chromatin in the absence of sequence-specific recruitment, and without requirement for a small RNA positive-feedback loop associated with RNAi, or other known modification systems such as DNA CpG methylation, strongly suggest that histones modified by H3K9 methylation can act as carriers of epigenetic information. This conclusion is supported by (1) our demonstration that deletion of the fission yeast putative histone H3K9 demethylase, epel+, stabilizes the epigenetic OFF state and allows its transmission through >50 cell divisions, and (2) the requirement for the Clr4 methyltransferase chromodomain, a domain that recognizes di- and tri-methylated H3K9, suggesting a direct read-write mechanism for this mode of epigenetic inheritance.

Several recent studies have described the transgenera-tional inheritance of environmentally-induced changes in gene expression from parent to offspring (41). The mechanism of this transgenerational inheritance has not been fully defined but appears to occur via both small RNA-dependent and -independent pathways. In C. elegans, plants, fission yeast, and possibly other systems, the transmission of histone modification patterns is often coupled to small RNA generation and/or CpG DNA methylation (42–44). The latter pathways can form positive feedback loops that help maintain histone modification patterns (2, 45). This coupling of positive feedback loops would increase the rate of reestablishment of silent domains and thus counteract the erasure activity of enzymes such as Epel or mechanisms that increase the rate of histone turnover.

A previous study used a small molecule dimerization strategy to show that ectopically-induced domains of H3K9 methylation at the Oct4 locus in murine fibroblasts can be maintained after the removal of the small molecule inducer by a mechanism that is reinforced by CpG DNA methylation (46). However, unlike the experiments presented here, the use of the Oct4 locus, which is normally packaged into heterochromatin in fibroblasts (46), precludes any conclusions about sequence-independent inheritance as contributions from locus-specific sequence elements that normally silence Oct4 in differentiated cells cannot be ruled out. It therefore remains to be determined whether H3K9 methylation can be inherited independently of specific DNA sequences or modulation of H3K9 demethylase activity in mammalian cells. Also, in fission yeast, a previous study reported that ectopic heterochromatin-dependent silencing of an ade6+ allele induced by a centromeric DNA fragment is maintained in an RNAi-dependent manner after excision of the centromeric DNA fragment (47), suggesting that a small RNA amplification loop may somehow be established at the ade6+ locus which helps maintain the silent state. However, these findings contradict other studies, which have demonstrated that silencing of ura4+ alleles by the generation of small RNA from a hairpin could not be maintained in the absence of the inducing hairpin (48, 49). Our findings indicate that even in the absence of coupling to other positive feedback loops, or sequence-dependent initiation signals, H3K9 methylation defines a silent state that can be epige-netically inherited (fig. S7). Maintenance of the OFF state is likely determined by the balance between the rate of H3K9 methylation by the Clr4 reader-writer module and the loss rate due to demethylation by an Epel-dependent mechanism, transcription-coupled nucleosome exchange, and dilution of histones during DNA replication.

Although demethylase activity for the S. pombe Epel protein has not yet been demonstrated in vitro, key residues required for demethylase activity in other Jumonji domain proteins are conserved in Epel and required for its in vivo effects on silencing (30, 50), and its effect on initiator-independent inheritance of heterochromatin (this study, Fig. 4C). In addition, a recent study showed that the activity of human PHF2, another member of the Jumonji domain protein family, is regulated by phosphorylation (51), raising the possibility that a post-translational modification or co-factor may be required for reconstitution of Epel demethylase activity. Regulation of histone demethylation activity may play a broad role in determining the reversibility of epigenetic states. Although it is unknown whether Epel activity or levels regulate epigenetic transitions in S. pombe, regulation of histone demethylase activity has been implicated in control of developmental transitions in multicellular eukaryotes. In mouse embryonic stem cells, the pluripotency transcription factor Oct4 activates the expression of Jumonji domain Jmjdla and Jmjd2c H3K9 deme-thylases and this activation appears to be important for stem cell self-renewal (52). An attractive possibility is that as epigenetic states become established during transition from pluripotency to the differentiated state, reduction in the expression of H3K9 demethylases helps stabilize the differentiated state (52). In another example, down-regulation of the amine oxidase family histone demethylase LSD1 during activation of individual olfactory receptor (OR) genes in the mammalian nose has been suggested to create an “epigenetic trap” that prevents the activation of additional OR genes (53). More generally, H3K9 demethylases may act as surveillance enzymes that prevent the formation of spurious H3K9 methylated domains, which may lead to epigenetic mutations and gene inactivation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Shetty for help with tetrad dissections, D. Shea for help in data processing, DN A 2.0 (Menlo Park, CA) for synthesis of the plasmid containing tetO binding sites, D. Landgraf for the gift of a yeast codon optimized GFP plasmid, T. Hattori and S. Koide for a gift of H3K9me3 recombinant antibody, and members of the Moazed lab for helpful discussions and comments, in particular, E. Egan, N. Iglesias, and J. Xiol for providing valuable experimental help and advice, and R. Behrouzi for advice and help with FACS analysis. The raw and processed ChlP-seq data are publicly available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE63304. This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (CDP-5025-14 to K.R.) and a grant from the NIH (GM072805 to D.M.). G.J. was supported partly by an NIH training grant (T32 GM007226). D.M. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trlthorax group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. Medline doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moazed D. Mechanisms for the Inheritance of chromatin states. Cell. 2011;146:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.013. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cfill.?011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251260. doi: 10.1038/38444. Medline doi:10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenuwein T, Allls CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. Medline doi:10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kouzarldes T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrelber SL, Bernstein BE. Signaling network model of chromatin. Cell. 2002;111:771–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01196-0. Medline doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rando OJ. Combinatorial complexity In chromatin structure and function: Revisiting the histone code. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 2012;22:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.013. Mexllina doi:10.1016/j.grie.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson V, Chalkley R. Separation of newly synthesized nucleohlstone by equilibrium centrlfugation in cesium chloride. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3952–3956. doi: 10.1021/bi00716a021. Medline doi:10.1021/bi00716a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sogo JM, Stahl H, Koller T, Knlppers R. Structure of replicating simian virus 40 mlnichromosomes. The replication fork, core histone segregation and terminal structures. J. Mot. Biol. 1986;189:189–204. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90390-6. Medline doi:10.1016/0022-2836(86)90390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radman-Livaja M, Verzljlbergen KF, Welner A, van Welsem T, Friedman N, Rando OJ, van Leeuwen F. Patterns and mechanisms of ancestral histone protein Inheritance In budding yeast. PLOS Biol. 2011;9:e1001075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001075. Medline doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Probst AV, Dunleavy E, Almouznl G. Epigenetic Inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:192–206. doi: 10.1038/nrm2640. Medline doi:10.1038/nrm2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strahl BD, Allls CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. Medline doi:10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner BM. Histone acetylatlon and an epigenetic code. BioEssays. 2000;22:836–845. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<836::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-X. Medline doi:10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<836::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ptashne M. On the use of the word ‘epigenetic’. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R233–R236. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.030. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cuh.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margueron R, Reinberg D. Chromatin structure and the Inheritance of epigenetic Information. Nat Rev. Genet. 2010;11:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrg2752. Medline doi:10.1038/nrg2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng TH, Gartenberg MR. Yeast heterochromatin Is a dynamic structure that requires silencers continuously. Genes Dev. 2000;14:452–463. Medline. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes SG, Broach JR. Silencers are required for Inheritance of the repressed state in yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1021–1032. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.1021. Medline doi:10.1101/gari.10.8.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengupta AK, Kuhrs A, Muller J. General transcriptional silencing by a Polycomb response element In Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:1959–1965. doi: 10.1242/dev.01084. Medline doi:10.1242/dev.01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busturia A, Wightman CD, Sakonju S. A silencer is required for maintenance of transcriptional repression throughout Drosophila development. Development. 1997;124:4343–4350. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4343. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buhler M, Gasser SM. Silent chromatin at the middle and ends: Lessons from yeasts. EMBOJ. 2009;28:2149–2161. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.185. Medline doi:10.1038/emhoj.2009.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allshlre RC, Javerzat JP, Redhead NJ, Cranston G. Position effect variegation at fission yeast centromeres. Cell. 1994;76:157–169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90180-5. Medline doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grewal SI, Klar AJ. Chromosomal inheritance of epigenetic states in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell. 1996;86:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80080-x. Medline doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80080-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakayama J, Klar AJ, Grewal SI. A chromodomain protein, Swi6, performs imprinting functions in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell. 2000;101:307317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80840-5. Medline doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chien CT, Buck S, Sternglanz R, Shore D. Targeting of SIR1 protein establishes transcriptional silencing at HM loci and telomeres in yeast. Cell. 1993;75:531–541. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90387-6. Medline doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagansky A, Folco HD, Almeida R, Pidoux AL, Boukaba A, Simmer F, Urano T, Hamilton GL, Allshire RC. Synthetic heterochromatin bypasses RNAi and centromeric repeats to establish functional centromeres. Science. 2009;324:1716–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1172026. Medline doi:10.1126/science.1172026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy BD, Wang Y, Niu L, Higuchi EC, Marguerat SB, Bahler J, Smith GR, Jia S. Elimination of a specific histone H3K14 acetyltransferase complex bypasses the RNAi pathway to regulate pericentric heterochromatin functions. Genes Dev. 2011;25:214–219. doi: 10.1101/gad.1993611. Medline doi:10.1101/gari.1993611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tadeo X, Wang J, Kallgren SP, Liu J, Reddy BD, Qiao F, Jia S. Elimination of shelterin components bypasses RNAi for pericentric heterochromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2489–2499. doi: 10.1101/gad.226118.113. Medline doi:10.1101/gad.226118.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trewick SC, Mine E, Antonelli R, Urano T, Allshire RC. The JmjC domain protein Epel prevents unregulated assembly and disassembly of heterochromatin. EMBO J. 2007;26:4670–4682. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601892. Medline doi:10.1038/sj.emhoj.7601892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. Medline doi:10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gómez EB, Espinosa JM, Forsburg SL. Schizosaccharomyces pombe mst2+ encodes a MYST family histone acetyltransferase that negatively regulates telomere silencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8887–8903. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.8887-8903.2005. Medline doi:10.1128/MCB.25.20.8887-8903.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roguev A, Schaft D, Shevchenko A, Aasland R, Shevchenko A, Stewart AF. High conservation of the Setl/Rad6 axis of histone 3 lysine 4 methylation in budding and fission yeasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:8487–8493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209562200. Medline doi:10.1074/jhc.M209562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyoshi T, Kanoh J, Saito M, Ishikawa F. Fission yeast Pot1-Tpp1 protects telomeres and regulates telomere length. Science. 2008;320:1341–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1154819. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volpe TA, Kidner C, Hall IM, Teng G, Grewal SI, Martienssen RA. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science. 2002;297:1833–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1074973. Medline doi:10.1126/science.1074973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadaie M, Iida T, Urano T, Nakayama J. A chromodomain protein, Chp1, is required for the establishment of heterochromatin in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2004;23:3825–3835. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600401. Medline doi:10.1038/sj.emhoj.7600401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halic M, Moazed D. Dicer-independent primal RNAs trigger RNAi and heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2010;140:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.019. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes-Turcu FE, Zhang K, Zofall M, Chen E, Grewal SI. Defects in RNA quality control factors reveal RNAi-independent nucleation of heterochromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:1132–1138. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2122. Medline doi:10.1038/nsmh.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2001;292:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. Medline doi:10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang K, Mosch K, Fischle W, Grewal SI. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:381–388. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1406. Medline doi:10.1038/nsmh.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heard E, Martienssen RA. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: Myths and mechanisms. Cell. 2014;157:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.045. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu SG, Pak J, Guang S, Maniar JM, Kennedy S, Fire A. Amplification of siRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans generates a transgenerational sequence-targeted histone H3 lysine 9 methylation footprint. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:157–164. doi: 10.1038/ng.1039. Medline doi:10.1038/ng.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong X, Du J, Hale CJ, Gallego-Bartolomé J, Feng S, Vashisht AA, Chory J, Wohlschlegel JA, Patel DJ, Jacobsen SE. Molecular mechanism of action of plant DRM de novo DNA methyltransferases. Cell. 2014;157:1050–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.056. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Motamedi MR, Verdel A, Colmenares SU, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell. 2004;119:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. Medline doi:10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hathaway NA, Bell O, Hodges C, Miller EL, Neel DS, Crabtree GR. Dynamics and memory of heterochromatin in living cells. Cell. 2012;149:1447–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.052. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wheeler BS, Ruderman BT, Willard HF, Scott KC. Uncoupling of genomic and epigenetic signals in the maintenance and inheritance of heterochromatin domains in fission yeast. Genetics. 2012;190:549–557. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137083. Medline doi:10.1534/genetics.H1.137083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iida T, Nakayama J, Moazed D. siRNA-mediated heterochromatin establishment requires HP1 and is associated with antisense transcription. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.003. Medline doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu R, Jih G, Iglesias N, Moazed D. Determinants of heterochromatic siRNA biogenesis and function. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:262–276. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.014. Medline doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Y, Whetstine JR. Dynamic regulation of histone lysine methylation by demethylases. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.010. Medline doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baba A, Ohtake F, Okuno Y, Yokota K, Okada M, Imai Y, Ni M, Meyer CA, Igarashi K, Kanno J, Brown M, Kato S. PKA-dependent regulation of the histone lysine demethylase complex PHF2-ARID5B. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:668–675. doi: 10.1038/ncb2228. Medline doi:10.1038/nch2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, George J, Ng HH. Jmjdla and Jmjd2c histone H3 Lys 9 demethylases regulate self-renewal in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2545–2557. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588207. Medline doi:10.1101/gari.1588207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lyons DB, Allen WE, Goh T, Tsai L, Barnea G, Lomvardas S. An epigenetic trap stabilizes singular olfactory receptor expression. Cell. 2013;154:325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.039. Medline doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, III, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. Medline doi:10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bahler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, III, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. Medline doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YFA292>3.0.CO:2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Egan ED, Braun CR, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Post-transcriptional regulation of meiotic genes by a nuclear RNA silencing complex. RNA. 2014;20:867–881. doi: 10.1261/rna.044479.114. Medline doi:10.1261/rna.044479.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hattori T, Taft JM, Swist KM, Luo H, Witt H, Slattery M, Koide A, Ruthenburg AJ, Krajewski K, Strahl BD, White KP, Farnham PJ, Zhao Y, Koide S. Recombinant antibodies to histone post-translational modifications. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:992–995. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2605. Medline doi:10.1038/nmeth.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.