Abstract

Background

Higher serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D] levels are associated with decreased colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence. In this retrospective study of stage IV CRC patients, we evaluate whether 25(OH)D levels at diagnosis correlate with survival.

Methods

Stored sera from carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) measurements obtained between February 2005 and March 2006 were screened. The first 250 patients with CEA ±30 days of stage IV CRC diagnosis were included. Serum 25(OH)D levels were determined and categorized as adequate ≥30 ng/mL, or deficient <30 ng/mL. Multivariable Cox regression models controlling for albumin and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status were used to investigate whether higher 25(OH)D levels were associated with prolonged survival.

Results

A total of 207 patients (83%) were vitamin D-deficient (median, 21 ng/mL), with deficiencies significantly more likely among non-Hispanic black patients (P=0.009). Higher levels were associated with prolonged survival in categorical variable analysis: adequate vs deficient, hazard ratio 0.61, 95% CI 0.38–0.98, P=0.041.

Conclusions

A majority of newly diagnosed stage IV CRC patients are vitamin D-deficient. Our data suggest that higher 25(OH)D levels are associated with better overall survival. Clinical trials to determine whether aggressive vitamin D repletion would improve outcomes for vitamin D-deficient CRC patients are warranted.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Vitamin D, Epidemiological

Introduction

Vitamin D insufficiency is now seen as pandemic. An estimated 40–80% of people in the United States have serum vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL (1), a threshold felt by many investigators to be appropriate for skeletal health (2–4). The Institute of Medicine defines vitamin D adequacy as ≥20 ng/mL for normal healthy individuals (5), however it can be argued that higher levels are indicated in the presence of chronic disease or for those at risk of musculoskeletal complications of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency (6). Furthermore, vitamin D deficiency is more common among elderly patients (7) and African Americans (8), two groups at high risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality.

There is evidence that vitamin D levels (7,9–14) and possibly vitamin D receptor polymorphism (15–20) may play a predictive if not therapeutic role in improved survival for patients with CRC. The protective effects of vitamin D result from its role as a nuclear transcription factor that regulates cell growth (21,22), differentiation (23,24), apoptosis (25), and a wide range of cellular mechanisms crucial to the development and progression of cancer (23).

While there is some consensus as to what optimal serum vitamin D levels are for bone health (4,6,26,27), there are no clear guidelines as to what levels are optimal for patients already diagnosed with cancer or who are undergoing cancer therapy. Meta-analysis of vitamin D levels in association with colon cancer shows a 50% lower risk of CRC with serum vitamin D levels ≥33 ng/mL (28), providing some insight into cancer prevention guidelines regarding serum vitamin D status. The pooled odds ratio (OR) for highest versus lowest quintile was 0.49 [P < 0.0001, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.35–0.68]. Evaluations in breast cancer patients have demonstrated statistically significant improvements in survival with serum levels of 40 ng/mL (29,30) and improved tumor characteristics with enhanced serum vitamin D levels (31).

Evidence suggests that vitamin D levels are frequently deficient in patients who are diagnosed with CRC (32,33). Other preliminary evidence suggests that the degree of vitamin D deficiency has prognostic significance, with a greater degree of deficiency correlating with poorer overall survival (12,34,35) and one report showing selective survival benefit with improved serum vitamin D levels in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy (36).

To further characterize the vitamin D status of advanced CRC patients at the time of diagnosis and determine whether enhanced vitamin D status is predictive of outcomes, we determined serum vitamin D levels in patients newly diagnosed with stage IV CRC and compared their vitamin D status with survival.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

Starting in 1974 Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) began an extensive bank of frozen sera on all patients for whom tumor markers are ordered. For this study, stored sera from carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) measurements in patients with stage IV CRC were screened for study inclusion. A sample size of 250 was chosen for convenience. Patients were initially identified by their ICD-9 codes for rectal cancer and for colon cancer, excluding patients with appendiceal cancer. Patients identified for inclusion were cross-referenced for nodal and secondary visceral metastases. Survival data was ascertained on all potential patients through the cancer death registry. In order to capture those patients with unusually long survival, we began screening in March 2006 and worked sequentially backwards until there were 250 serial samples available. The first 250 patients with CEA drawn ±30 days of stage IV CRC diagnosis and for whom survival data were available were included in this analysis. The final study population was initially diagnosed with stage IV CRC between February 2005 and March 2006.

A waiver of authorization application from the MSK Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board was obtained to access archived patient clinical data for the purpose of identifying patients’ frozen serum samples for the vitamin D analysis. All patients had previously signed consent for their sera to be frozen under a general research protocol approved by the MSK Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board.

Exposure Assessment

Serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D] analysis for all patients was determined using the radioimmunoassay procedure from DiaSorin Inc. (Stillwater, MN). As one of three methods, the others being high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, the DiaSorin assay is an established standard that can be used to quantitatively detect total vitamin D levels (37). To verify the sera stability for 25(OH)D levels, an initial 50 samples were analyzed. After demonstrating appropriate variability for levels in these samples, the remaining 200 samples were analyzed. Demographic data including concurrent risk factors for vitamin D deficiency such as age, ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI), as well as medication use and supplemental vitamin intake were obtained from patient charts. Additional factors known to influence CRC mortality including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG), number of metastatic sites, serum albumin, surgical resection, and type of chemotherapy received were also assessed.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed for patient demographics and clinical characteristics. Serum 25(OH)D levels were graded as deficient (<30 ng/mL) or adequate (≥30 ng/mL). There is debate regarding which specific serum cut points define adequacy (6), however these values are supported by the Endocrine Society for skeletal health (4). The serum 25(OH)D levels and patient characteristics are also displayed in quintiles to facilitate comparison with other published reports (12,29).

The association between vitamin D status and overall survival was assessed univariately and after adjustment for ECOG and albumin using a Cox survival regression model. Vitamin D was analyzed separately as a binary variable for adequate versus deficient levels (the primary analysis) and as a continuous variable per ng/mL. In an attempt to estimate optimal serum 25(OH)D levels in patients with CRC, we categorized values into groups by serum deciles and reported summary statistics of median survival.

We also investigated a differential effect that vitamin D may have on survival by chemotherapy type, by adding an interaction term with 25(OH)D level and receipt of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) chemotherapy. The significance of the interaction was investigated adjusting for albumin and ECOG, with no adjustment, vitamin D entered as a continuous variable, and vitamin D dichotomized at 30 ng/mL. We determined whether the addition of vitamin D improved the discrimination by comparing the Harrell’s C-index from a Cox model including ECOG and albumin with a model including ECOG, albumin, and vitamin D. The C-indices are corrected for optimism using bootstrap methods. We adjusted for albumin and ECOG status as predictors of survival and used linear regression to describe associations with other demographic variables. We tested univariate associations between 25(OH)D levels and race, BMI, age, and sex using linear regression. All analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Vitamin D Levels

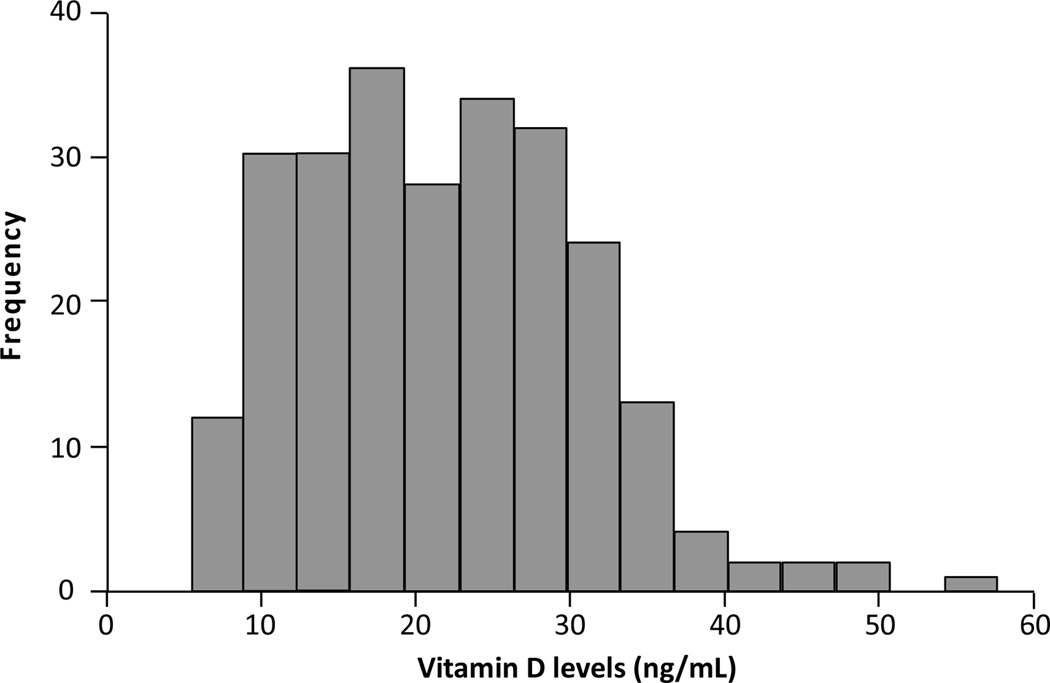

Patient characteristics for all 250 patients are summarized in Table 1. Median 25(OH)D was 21 ng/mL and 207 (83%) patients had levels <30 ng/mL. There were 43 (17%) patients with 25(OH)D ≥30 ng/mL and only 7 (3%) of 250 patients had serum levels >40 ng/mL. A histogram of vitamin D levels is given in Figure 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients diagnosed with mCRC, stratified by quintiles of vitamin D levels (n=50 each group)

| Characteristic | Overall N=250 |

Quintile 1 5.4 to 13.5 ng/mL |

Quintile 2 13.6 to 18.3 ng/mL |

Quintile 3 18.4 to 23.8 ng/mL |

Quintile 4 23.9 to 29.6 ng/mL |

Quintile 5 29.7 to 57.6 ng/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63 (52, 73) | 59 (48, 69) | 67 (51, 76) | 57 (49, 69) | 67 (55, 76) | 65 (55, 74) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (n=248) | 26 (23, 29) | 25 (24, 29) | 26 (23, 31) | 27 (25, 30) | 26 (22, 28) | 26 (22, 31) |

| Race | ||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 201 (80%) | 32 (64%) | 42 (84%) | 44 (88%) | 43 (86%) | 40 (80%) |

| White Hispanic | 13 (5%) | 5 (10%) | 2 (4%) | 0 | 3 (6%) | 3 (6%) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 16 (6%) | 9 (18%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) |

| Black Hispanic | 5 (2%) | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (6%) |

| Asian | 8 (3%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Other/Unknown | 7 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| ECOG score | ||||||

| 0 | 116 (46%) | 19 (38%) | 23 (46%) | 31 (62%) | 20 (40%) | 23 (46%) |

| 1 | 75 (30%) | 19 (38%) | 16 (32%) | 9 (18%) | 16 (32%) | 15 (30%) |

| 2 | 48 (19%) | 11 (22%) | 10 (20%) | 8 (16%) | 9 (18%) | 10 (20%) |

| 3 | 10 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (8%) | 2 (4%) |

| 4 | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Albumin, g/mL (n=241) | 3.8 (3.4, 4.2) | 3.5 (3.2, 3.8) | 3.9 (3.4, 4.2) | 3.9 (3.6, 4.3) | 3.8 (3.3, 4.1) | 4.0 (3.5, 4.3) |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 21 (15, 29) | — | — | — | — | — |

| 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL | 207 (83%) | — | — | — | — | — |

Data presented as median (interquartile range) or frequency (percentage). Some total percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding. 25(OH)D, serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer.

FIG. 1.

Histogram of vitamin D levels in patients newly diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer (n=250).

Association of Vitamin D Levels with Patient Characteristics

Non-Hispanic black patients were significantly more likely than others to have vitamin D deficiency (P = 0.009). 25(OH)D levels were not significantly associated with other basic demographic variables including age, sex, BMI values, or ECOG scores. Albumin levels tended to be higher with increasing levels of vitamin D.

The sites of metastatic disease and treatment characteristics are given in Table 2. The majority of patients had only 1 site of disease at diagnosis (n = 203, 81%). The most common site of metastatic disease was the liver (67%), followed by peritoneum (21%), lung (19%), large bowel (8%), small bowel (4%), and pleura (2%). Almost one-half of patients (42%) received oxaliplatin-based regimens as their first-line chemotherapy, and only 19% received irinotecan-based regimens. Among patients who received either oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based first-line regimens, nearly half (47%) also received bevacizumab.

TABLE 2.

Sites of metastatic disease and first-line chemotherapy regimens (n=250)

| Number of metastatic sites at diagnosisa | |

| 1 | 203 (81%) |

| 2 | 43 (17%) |

| 3 | 3 (1%) |

| 4 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Sites of metastatic disease at diagnosisb | |

| Liver | 168 (67%) |

| Peritoneum | 53 (21%) |

| Lung | 48 (19%) |

| Large bowel | 19 (8%) |

| Small bowel | 10 (4%) |

| Pleura | 4 (2%) |

| First-line chemotherapy regimena | |

| FOLFOXc | 46 (18%) |

| FOLFOX-B | 45 (18%) |

| FOLFIRI-B | 19 (8%) |

| Floxuridine | 16 (6%) |

| FOLFIRIc | 16 (6%) |

| Other | 55 (22%) |

| None | 53 (21%) |

| Basis of first-line chemotherapy regimen | |

| Oxaliplatin alone | 55 (22%) |

| Oxaliplatin + bevacizumab | 48 (19%) |

| Irinotecan alone | 23 (9%) |

| Irinotecan + bevacizumab | 22 (9%) |

| Bevacizumab alone | 4 (2%) |

| Irinotecan + oxaliplatin | 2 (1%) |

Total percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Patients with >1 site of metastatic disease are counted once for each site.

Infusional or bolus 5-fluorouracil (5FU).

FOLFOX: 5FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-B adds bevacizumab).

FOLFIRI: 5FU, leucovorin, irinotecan (FOLFIRI-B adds bevacizumab).

Vitamin D Levels and Outcomes

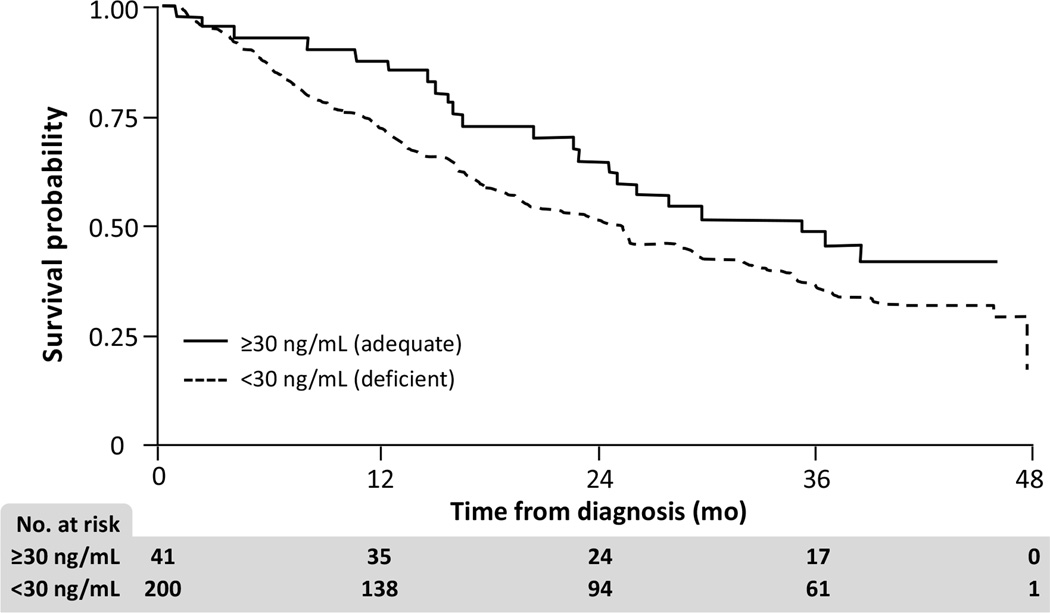

The multivariable survival analysis excluded 9 patients without data on albumin. Among the 241 patients included in the survival analysis, there were 153 deaths. Median follow-up for those still alive at the end of the study was 41 months. Results of Cox regression are given in Table 3. Kaplan-Meier survival probabilities stratified by 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL versus ≥30 ng/mL are given in Figure 2.

TABLE 3.

Association between vitamin D and survival in patients diagnosed with mCRC (n=241)a

| Vitamin D | Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysisb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Adequate vs deficient | 0.70 | 0.45, 1.10 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.38, 0.98 | 0.041 |

| Continuous per ng/mL | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.036 | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.076 |

Cox proportional hazards regression. Vitamin D analyzed separately as a binary variable for adequate vs deficient levels, and as a continuous variable per ng/mL.

Nine patients excluded due to lack of albumin data.

Adjusted for albumin and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer.

FIG. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival probabilities, stratified by vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL and ≥30 ng/mL (n=241).

On multivariable analysis controlling for ECOG and albumin, we observed borderline results for the association between vitamin D and survival. When vitamin D was entered as a binary variable for adequate versus deficient levels, the independent P-value was 0.041 [hazard ratio (HR) 0.61], suggesting that adequate 25(OH)D levels correspond to prolonged survival (95% CI 0.38–0.98). The statistical significance did not hold when vitamin D was entered as a continuous variable: independent P-value 0.076 (HR 0.98 per ng/mL; 95% CI 0.96–1.00). The concordance index of the base model (ECOG, albumin) was 0.648, and was not enhanced by the addition of vitamin D when entered as a continuous or binary variable.

We investigated whether survival differed based on vitamin D levels and chemotherapy type together by testing the significance of this interaction in the Cox model. We did not find evidence that survival differed by chemotherapy type and vitamin D levels when analyzed jointly.

Median survival times across 25(OH)D levels categorized by serum deciles are shown in Table 4. There was a 7-month median survival difference between those with serum levels ≥30 mg/mL (35 months) and those with levels of 20–29 ng/mL (28 months). Those with baseline 25(OH)D levels of 10–19 ng/mL had a median survival of 22 months.

TABLE 4.

Median survival across serum vitamin D deciles in 241 evaluable patients

| 25(Oh)D Level, ng/mL | n | Median survival |

|---|---|---|

| <10 | 24 | 13 months |

| 10–19 | 82 | 22 months |

| 20–29 | 94 | 28 months |

| ≥30 | 41 | 35 months |

For a typical patient (ECOG score 0; albumin 3.8 g/mL corresponding to median levels), the predicted 2-year survival probability was 65% for a patient with 25(OH)D levels of 28.5 (corresponding to the 75th percentile) and 58% for a patient with levels of 15.0 (corresponding to the 25th percentile); this corresponds to an absolute difference in 2-year survival of 7%.

Discussion

The vast majority of patients with newly diagnosed stage IV CRC have low 25(OH)D levels at the time of cancer diagnosis. Serum levels <30 ng/mL were found in 207 (83%) of our patient samples. Only 7 (3%) of 250 patients had levels >40 ng/mL. Dividing serum D levels into deciles by ng/mL value indicates progressively longer survival with increasing serum D levels, suggesting levels ≥30 ng/mL are optimal (Table 4).

Although there was no demonstrated association between increasing BMI and vitamin D insufficiency similar to another study result (36), the range of BMI values in our population was narrow, and this finding also contrasts with other studies that do report an association (12,29). In addition, a recent large case series of patients with various cancers significantly associated every 1 kg/m2 BMI increase with a 0.42 ng/mL decline in serum 25(OH)D levels. In CRC patients for every 1 kg/m2 BMI increase, declines in serum 25(OH)D levels were even greater (0.46 ng/mL) (38).

Our finding that black non-Hispanic patients had significantly lower serum 25(OH)D levels is corroborated by a large population study that indicates vitamin D deficiency contributes to excess mortality from CRC among African-Americans (39). Those with lower serum albumin levels also indicated a tendency toward lower vitamin D levels.

Only 17% of our patients had adequate vitamin D levels. Lower 25(OH)D values demonstrated a consistent pattern of association with decreased survival, although achieving statistical significance varied based on the type of analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed survival differences between those with levels ≥30 ng/mL versus <30 ng/mL. Multivariate analyses showed vitamin D was significantly associated with survival as a categorical (P = 0.041) but not continuous variable (P = 0.076). Most of the patients had low serum vitamin D levels and very few had normal values; thus it is possible that a more balanced distribution over a much wider range of vitamin D values would show a survival benefit. Whether ongoing vitamin D supplementation to enhance serum 25(OH)D would improve survival in newly diagnosed CRC patients is unclear, and clinical trials designed to evaluate such outcomes are warranted to answer this question.

Previous studies have demonstrated improved survival in CRC patients with increased serum vitamin D levels (35), particularly for those with advanced disease (12) although this finding is not universal (36). The Intergroup Trial N9741 did not find an association for enhanced serum vitamin D status in survival, time to disease progression, or tumor response (36). However, when survival and vitamin D levels by chemotherapy regimen was analyzed, there were improved outcomes in patients randomized to the FOLFOX arm, while those randomized to irinotecan had worse survival. There is preclinical evidence that vitamin D may potentiate platinum-based chemotherapy regimens which could lead to improved clinical outcomes in patients with higher serum 25(OH)D levels (40–43). While our patients were not selected based on their chemotherapy regimen, 19% of our patients received irinotecan, compared with 22% in the N9741 trial, where worse outcomes were associated with enhanced serum vitamin D status. Our study did not demonstrate an interaction between survival, serum 25(OH)D levels, and chemotherapy regimen when vitamin D was tested as univariate, multivariate, continuous, or categorical variables.

Study limitations include accuracy of ECOG status, which was extracted from chart narratives for many patients. Secondly, patients with insufficient 25(OH)D levels did not receive vitamin D supplementation, so we are unable to confirm that enhancing their vitamin D status could improve outcomes. Most of the metastatic tumor locations in our study were liver metastases. Although we controlled for ECOG status and serum albumin levels in our analysis, it is possible there may be residual confounders not already identified.

For patients with stage IV CRC, these data suggest that higher vitamin D levels at diagnosis are associated with an improvement in survival. Even a small increase in survival advantage with enhanced serum vitamin D levels would be of important clinical significance. Considering the low economic cost and excellent safety profile of vitamin D supplementation, additional clinical evaluation is warranted using vitamin D supplementation in patients with advanced CRC to determine whether aggressive repletion would improve clinical outcomes in vitamin D-deficient CRC patients. Completing such a study may be challenging however, as government funding for large clinical trials is decreasing and there is no profit incentive for pharmaceutical companies to fund such a trial.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and a grant from the Gateway for Cancer Research Foundation.

Ingrid Haviland provided editorial support in the preparation and submission of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Martins D, Wolf M, Pan D, Zadshir A, Tareen N, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the United States: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1159–1165. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic and consequences for nonskeletal health: mechanisms of action. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JH, O'Keefe JH, Bell D, Hensrud DD, Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency an important, common, and easily treatable cardiovascular risk factor? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:342–357. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieg J, Sieg A, Dreyhaupt J, Schmidt-Gayk H. Insufficient vitamin D supply as a possible co-factor in colorectal carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2729–2733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Willett WC. Cancer incidence and mortality and vitamin D in black and white male health professionals. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2467–2472. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovannucci E. Vitamin D and cancer incidence in the Harvard cohorts. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannucci E. Epidemiology of vitamin D and colorectal cancer: casual or causal link? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, Grant WB, Mohr SB, et al. Vitamin D and prevention of colorectal cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, Feskanich D, Hollis BW, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2984–2991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu K, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Hollis BW, et al. A nested case control study of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1120–1129. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannucci E. Epidemiology of vitamin D and colorectal cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2013;13:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matusiak D, Murillo G, Carroll RE, Mehta RG, Benya RV. Expression of vitamin D receptor and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1{alpha}-hydroxylase in normal and malignant human colon. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2370–2376. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murtaugh MA, Sweeney C, Ma KN, Potter JD, Caan BJ, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, dietary promotion of insulin resistance, and colon and rectal cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:35–43. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slattery ML, Herrick J, Wolff RK, Caan BJ, Potter JD, et al. CDX2 VDR polymorphism and colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2752–2755. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kure S, Nosho K, Baba Y, Irahara N, Shima K, et al. Vitamin D receptor expression is associated with PIK3CA and KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2765–2772. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Touvier M, Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R, et al. Meta-analyses of vitamin D intake, 25-hydroxyvitamin D status, vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1003–1016. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muindi JR, Adjei AA, Wu ZR, Olson I, Huang H, et al. Serum vitamin D metabolites in colorectal cancer patients receiving cholecalciferol supplementation: correlation with polymorphisms in the vitamin D genes. Horm Cancer. 2013;4:242–250. doi: 10.1007/s12672-013-0139-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tangpricha V, Spina C, Yao M, Chen TC, Wolfe MM, et al. Vitamin D deficiency enhances the growth of MC-26 colon cancer xenografts in Balb/c mice. J Nutr. 2005;135:2350–2354. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holt PR, Arber N, Halmos B, Forde K, Kissileff H, et al. Colonic epithelial cell proliferation decreases with increasing levels of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:113–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan AV, Feldman D. Mechanisms of the anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions of vitamin D. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:311–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murillo G, Matusiak D, Benya RV, Mehta RG. Chemopreventive efficacy of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in colon cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Larriba MJ, Ordonez-Moran P, Palmer HG, Munoz A. Effects of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2669–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant WB, Holick MF. Benefits and requirements of vitamin D for optimal health: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:94–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heaney RP, Holick MF. Why the IOM recommendations for vitamin D are deficient. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:455–457. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, Grant WB, Mohr SB, et al. Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention: a quantitative meta analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Koo J, Hood N. Prognostic effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3757–3763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose AA, Elser C, Ennis M, Goodwin PJ. Blood levels of vitamin D and early stage breast cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141:331–339. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2713-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peppone LJ, Rickles AS, Janelsins MC, Insalaco MR, Skinner KA. The association between breast cancer prognostic indicators and serum 25-OH vitamin D levels. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2590–2599. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2297-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JE, Li H, Chan AT, Hollis BW, Lee IM, et al. Circulating levels of vitamin D and colon and rectal cancer: the Physicians' Health Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:735–743. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fakih MG, Trump DL, Johnson CS, Tian L, Muindi J, et al. Chemotherapy is linked to severe vitamin D deficiency in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0593-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giovannucci E. Epidemiological evidence for vitamin D and colorectal cancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(Suppl 2):V81–V85. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07s206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mezawa H, Sugiura T, Watanabe M, Norizoe C, Takahashi D, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and survival of patients with colorectal cancer: post-hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:347. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng K, Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Meyerhardt JA, Green EM, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: findings from Intergroup trial N9741. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1599–1606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arneson WL, Arneson DL. Current methods for routine clinical laboratory testing of Vitamin D levels. Lab Med. 2013;44:e38–e42. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vashi PG, Lammersfeld CA, Braun DP, Gupta D. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is inversely associated with body mass index in cancer. Nutr J. 2011;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiscella K, Winters P, Tancredi D, Hendren S, Franks P. Racial disparity in death from colorectal cancer: does vitamin D deficiency contribute? Cancer. 2011;117:1061–1069. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hershberger PA, McGuire TF, Yu WD, Zuhowski EG, Schellens JH, et al. Cisplatin potentiates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced apoptosis in association with increased mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK-1) expression. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Light BW, Yu WD, McElwain MC, Russell DM, Trump DL, et al. Potentiation of cisplatin antitumor activity using a vitamin D analogue in a murine squamous cell carcinoma model system. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3759–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffatt KA, Johannes WU, Miller GJ. Alpha,25dihydroxyvitamin D3 and platinum drugs act synergistically to inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milczarek M, Rosinska S, Psurski M, Maciejewska M, Kutner A, et al. Combined colonic cancer treatment with vitamin D analogs and irinotecan or oxaliplatin. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:433–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]