Abstract

Release of the free fatty acid arachidonic acid (AA) by cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) and its subsequent metabolism by the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes produces a broad panel of eicosanoids including prostaglandins (PGs). This study sought to investigate the roles of these mediators in experimental models of inflammation and inflammation-associated intestinal tumorigenesis. Using the dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) model of experimental colitis, we first investigated how a global reduction in eicosanoid production would impact intestinal injury by utilizing cPLA2 knockout mice. cPLA2 deletion enhanced colonic injury, reflected by increased mucosal ulceration and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Increased disease severity was associated with a significant reduction in the levels of several eicosanoid metabolites, including PGE2. We further assessed the precise role of PGE2 synthesis on mucosal injury and repair by utilizing mice with a genetic deletion of microsomal PGE synthase-1 (mPGES-1), the terminal synthase in the formation of inducible PGE2. DSS exposure caused more extensive acute injury as well as impaired recovery in knockout mice compared to wild-type littermates. Increased intestinal damage was associated with both reduced PGE2 levels as well as altered levels of other eicosanoids including PGD2. To determine whether this metabolic redirection impacted inflammation-associated intestinal tumorigenesis, ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice were exposed to DSS. DSS administration caused a reduction in the number of intestinal polyps only in ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice. These results demonstrate the importance of the balance of prostaglandins produced in the intestinal tract for maintaining intestinal homeostasis and impacting tumor development.

Keywords: Prostaglandins, Colitis, Tumorigenesis, Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, Cytosolic phosphlipase A2, Intestine

1. Introduction

Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) is the rate-limiting enzyme in the generation of arachidonic acid (AA) from membrane phospholipids. Following its inducible release, AA is metabolized by lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes producing a large panel of eicosanoids including leukotrienes, HETEs and prostaglandins (PGs). More specifically, AA metabolized by COX produces PGH2 which is subsequently acted upon by specific PG synthases to generate a number of PG metabolites [1]. PGs can protect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through maintenance of mucosal integrity, promotion of wound healing and limiting the inflammatory response [2-7]. Increased PG production occurs within the GI mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in experimental models of IBD, which may be an adaptive response to promote healing [5, 8-14]. In fact, administration of COX inhibitors exacerbates IBD symptoms, further supporting a protective role for PGs [15-22]. Additionally, in mouse studies, genetic deletion of COX-1, COX-2 or microsomal PGE synthase-1 (mPGES-1) results in greater susceptibility to chemically-induced colitis [23-25]. However, the effects of the deletion of these and other key lipid-producing enzymes on the production of metabolites other than PGE2 during intestinal inflammation and how they may contribute to disease pathogenesis, has not been explored.

PGs can also modulate intestinal tumorigenesis. For example, PGE2 is clearly associated with tumor promotion in experimental models while PGD2 can be tumor suppressive [26-29]. Specifically, PGE2 has been shown to enhance cell proliferation through effects on the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway, inhibit apoptosis through Bcl-2 and NF-kB and promote angiogenesis through induction of vascular endothelial growth factor [7]. However, the role of PGs in inflammation-associated intestinal tumorigenesis is less clear. Ishikawa and Herschman reported that neither COX-1 nor COX-2 are critical to the formation of colonic tumors in the azoxymethane (AOM)/dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) model of colitis-associated cancer [30]. In contrast, other groups have shown that pharmacological inhibition of COX-2 suppresses inflammation-associated colon tumorigenesis while exogenous administration of PGE2 had the opposite effect [31, 32].

In the following study, we have examined the requirement for PGs in the maintenance and repair of the intestinal epithelium following chemical-induced mucosal injury. Using the DSS injury model, we compared the extent of intestinal injury in mice with a genetic disruption of PG synthesis occurring at several key enzymatic steps in the AA synthetic cascade; namely, genetic deletion of cPLA2, the rate-limiting step in the release of AA from membrane phospholipid stores, and mPGES-1, the terminal synthase in the formation of PGE2. We report that the ability to maintain sufficient quantities of PGE2 is necessary for dampening the extent of acute DSS-induced inflammation within the intestinal mucosa and that loss of PGE2 is associated with altered levels of other eicosanoids. Interestingly, genetic deletion of mPGES-1 protected against inflammation-associated intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice. These results demonstrate the pathophysiological effects of altered PG balance in the GI tract.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Generation of mutant mice

Generation of the cPLA2−/− mouse line has been described previously [33]. Briefly, targeted inactivation of the cPLA2α (Pla2g4) gene was achieved by introduction of a neomycin resistance gene into exon 10, beginning with codon 187. The original knockout line was generated on a C57Bl/6J-129/Sv (B6-129) chimeric background. Mice were subsequently backcrossed >10 generations onto a pure BALB/c background. BALB/c cPLA2+/− heterozygous mice were then intercrossed to generate knockout mice for the following study. Wild-type mice used in this study were littermates of the homozygous null mice.

mPGES-1−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were provided by Merck-Frosst Canada, Ltd. The generation of this mouse line has been described previously [34]. C57BL/6 mPGES-1+/− mice were intercrossed to generate mPGES-1−/− and mPGES-1+/+ mice for the studies described. ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− compound mutant mice were created by crossing mPGES-1−/− females with ApcMin/+ male mice.

2.2. Induction of acute colitis

In Study 1, equal numbers of male and female 6-8 week-old cPLA2+/+ (n=20) and cPLA2−/− (n=20) mice were administered 3% DSS (MP Biomedical, Irvine, CA) in drinking water for 7 days. An additional group of cPLA2+/+ (n=10) and cPLA2−/− (n=10) mice received plain drinking water for 7 days. At sacrifice, spleen weights were recorded. Colons were excised, flushed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), formalin-fixed and Swiss-rolled for histological analysis. The percent of ulcerated colonic tissue was determined in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections and was calculated as the length of ulcerated tissue as a percent of the entire length of colon. Analysis was performed in a blinded manner. In Study 2, cPLA2+/+ (n=15) and cPLA2−/− (n=15) mice were administered 3% DSS in drinking water for 4 or 7 days or given plain drinking water for 7 days. At each time point, 5 mice of each genotype were sacrificed and colon tissue was snap frozen for subsequent analyses of cytokine expression and PG levels as described below. In Study 3, cPLA2+/+ (n=20) and cPLA2−/− (n=20) mice were administered 3% DSS in drinking water for 7 days, followed by plain water for an additional 7 days. Body weights were recorded daily and all mice were sacrificed on day 14.

In Study 1, equal numbers of male and female 6-8 week-old mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− (n=10) mice were administered 3% DSS in drinking water for 7 days. An additional group of mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− (n=10) mice received plain drinking water for 7 days. At sacrifice, spleen weights were recorded. Colons were excised, flushed with PBS, formalin-fixed and Swiss-rolled for histological analysis. The percent of ulcerated tissue was determined as described above. In Study 2, mPGES-1+/+ (n=15) and mPGES-1−/− (n=15) mice were administered 3% DSS in drinking water for 4 or 7 days or given plain drinking water for 7 days. At each time point, 5 mice of each genotype were sacrificed, and colon tissue was prepared for analyses of TNF expression and PG levels as described below. In Study 3, mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− (n=7) mice were administered 2% DSS in drinking water for 7 days, followed by plain water for 5 days. Body weights were recorded daily and all mice were sacrificed at day 12. A separate group of mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− (n=8) mice were given 2% DSS for 7 days then sacrificed. At sacrifice, colons were excised, Swiss-rolled and formalin-fixed for histological analysis. The percent of ulcerated tissue was determined in H&E-stained sections as described above. In Study 4, mPGES-1+/+ (n=6) and mPGES-1−/− (n=12) mice were administered 3% DSS in drinking water for 7 days, followed by plain water for 14 days. Body weights and mortality were recorded on a daily basis and all mice were sacrificed at day 21. Results for Study 4 are shown in the Supplementary Table 1.

2.3. Administration of DSS to ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice

Five-week old ApcMin/+ (n=16) and ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− (n=9) littermates on a C57BL/6 background were administered 2% DSS in drinking water for one week. After one week, DSS was replaced with plain drinking water for an additional four weeks until sacrifice. This course of treatment has been previously used with ApcMin/+ mice [35]. Age-matched ApcMin/+ (n=12) and ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− (n=9) littermate control mice received plain drinking water for the entire experimental period. Mice were weighed daily during DSS administration and then weekly during the five-week recovery period. At sacrifice, colons and small intestines were flushed with ice-cold PBS then formalin-fixed. For polyp enumeration, whole-tissue mounts were stained with 0.2% methylene blue and polyps were counted under a dissecting microscope. Representative images showing the identification of colon and small intestinal tumors are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. After macroscopic examination, tissues were Swiss-rolled, paraffin-embedded and tumor morphology was evaluated by a board-certified pathologist after H&E staining.

All mice used in these studies were housed in a ventilated, temperature-controlled (23°±°C), AAALAC–approved facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and were allowed access to Purina laboratory rodent chow 5001 (Purina, St. Louis, MO) and water ad libitum. All experiments were conducted according to the Institutional Guidelines for Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under an ethical protocol approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Connecticut Health Center.

2.4. Isolation of colonic lamina propria and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

mPGES-1+/+ and mPGES-1−/− mice were administered 3% DSS in drinking water or plain water for 7 days (n=3/group) then sacrificed. To isolate cells from the lamina propria (LP), colons were removed and flushed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, slit open longitudinally and cut into1-cm pieces. Tissues were placed into a solution containing Ca/Mg-free balanced salt solution (BSS) with 1mM Hepes, 2.5mM NaHCO3, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.15mg/ml dithioerythreitol and stirred at 37° C. Tissue pieces were then transferred to a solution containing BSS, 1.3mM EDTA, 1X HGPG and stirred at 37° C to remove the epithelium. The remaining tissue was placed into RPMI media containing 10% FBS, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 1x HGPG antibiotics, 100units/ml collagenase, 0.1mg/ml Dnase I and stirred at 37° C. Released cells were collected through a cell strainer and resuspended in 44% Percoll, which was underlayed with 67% Percoll and centrifuged to collect relevant cells for FACS analysis. Isolated cells were resuspended in staining buffer consisting of BSS, 3% FBS, and 0.1% sodium azide. Non-specific binding was blocked by the addition of anti-Fc mAb followed by incubation with GR1-PE (1:200; eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Flow cytometry was conducted on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with data analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). The fold change in Gr1-positive cells was determined by comparing the percent of Gr-1 positive cells out of the total number of cells isolated from the LP in control vs. DSS-exposed mice from each genotype.

2.5. Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from colons using Trizol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Two μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Superscript III RT (Invitrogen). Expression of TNF and IL-1β were determined by QRT–PCR using an ABI 7500 real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosciences, Foster city, CA). QRT–PCR reactions were performed in duplicate in 20μl volumes using 1μl 20x TaqMan Assay-on-Demand for TNF (ID=Mm00443258_m1) and IL-1β (ID=Mm00434228_m1). HPRT (ID=Mm00446968_m1) was used as an endogenous control gene to normalize expression. The cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. All qRT–PCR reactions were performed with a no template control and a positively expressed sample was used for generating the standard curve.

2.6. Eicosanoid Measurements

Colons and small intestines were homogenized in ice-cold phosphate buffer (2M KCl, 0.5M K2PO4) followed by 2 volumes of methanol added to the homogenates. Internal standards [d4]PGE2, [d4]TXB2, [d4]LTB4 and [d8]5–HETE (2ng each) were then added to each sample. Samples were centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 min. Supernatants were diluted with water to adjust the final methanol concentration below 15% and samples were extracted using solid-phase extraction cartridges (Strata C18–E, 100 mg/ml, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) pre-conditioned with 1ml of methanol and 1ml of water. The eluate (1ml of methanol) was dried down and solubilized in 40μl HPLC solvent A (8.3mM acetic acid buffered to pH 5.7 with ammonium hydroxide) plus 20μl HPLC solvent B (acetonitrile/methanol 65:35, v/v). An aliquot of each sample (25μl) was injected onto a C-18 HPLC column (Gemini 150 × 2 mm, 5 μm, Phenomenex) and eluted at a flow-rate of 200μl/min with a linear gradient from 45% to 98% of HPLC solvent B, which was increased from 45% to 75% in 12 min, to 98% in 2 min, and held at 98% for 11 min. The preconditioning of the solid-phase extraction cartridge essentially follows manufacturer's suggestions and has been previously published by our group [36, 37]. The HPLC system was directly interfaced into the electrospray source of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex API 3000, PE–Sciex, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada) where mass spectrometric analysis was performed in the negative ion mode using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) of the specific transitions (m/z).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were deparaffinized and incubated with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min at room temperature. Sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in sodium citrate and blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-APC or anti–β-catenin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Sections were washed and blocked in 10% goat serum then incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were washed and incubated with avidin-biotin complex reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by signal detection with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine solution (Vector Laboratories). Tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA and two-tailed, unpaired t-tests were performed to determine statistical significance by the probability of difference between means as indicated in the legends to each figure. A p-value equal to or less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values in the figures or written within the text are expressed as the means, plus or minus standard error of the mean (± SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Genetic deletion of cPLA2 enhances DSS-induced colonic injury

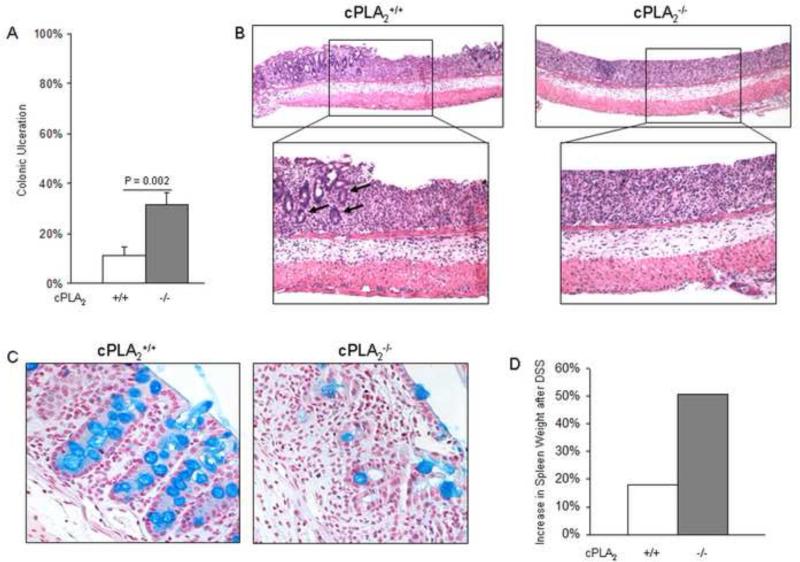

cPLA2 controls the release of AA from intracellular organelle membranes. Therefore we used mice with a genetic deletion of cPLA2 to evaluate how global suppression of eicosanoid formation might affect intestinal injury. To test this, we administered 3% DSS in drinking water to cPLA2+/+ and cPLA2−/− mice and determined the extent of acute intestinal injury. The colonic mucosa exhibited more extensive ulceration in the cPLA2−/− compared to cPLA2+/+ mice after 7 days of DSS exposure (31.3% ± 4.9% vs. 11.4% ± 3.1%; P = 0.002), indicating that disruption of AA release renders mice more susceptible to colonic injury (Fig. 1A). Histological examination of the ulcerated areas showed loss of colonic crypt architecture regardless of cPLA2 genotype. The damage, however, was more extensive in the cPLA2−/− colons (Fig. 1B). The presence of goblet cells was also determined in tissues from DSS-treated mice using Alcian blue staining. As shown in Figure 1C, mucin staining was reduced to a greater extent in the colons of the cPLA2−/− mice, a direct result of the reduced frequency of goblet cells. As an additional indicator of disease severity, spleen weights were measured after 7 days of DSS exposure. As shown in Figure 1D, spleens had a greater increase in weight in the cPLA2−/− mice compared to the wild-type controls (51% vs. 18%, respectively). Under control conditions, no ulcers were observed in either genotype nor was there any difference in spleen weight between wild-type and knockout mice (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that genetic deletion of cPLA2 sensitizes mice to acute DSS-induced injury.

Fig. 1.

Genetic deletion of cPLA2 enhances DSS-induced colitis. (A) 3% DSS was administered in drinking water to cPLA2+/+ (n=20) and cPLA2−/− (n=20) littermates for 7 days then sacrificed and the percentage of colonic ulceration was quantified in H&E-stained slides as described under Materials and Methods for each mouse and reported as an average. The p-value was determined by an unpaired t-test. (B) Representative H&E staining of colonic ulcerations from 7-day DSS exposed cPLA2+/+ and cPLA2−/− mice (40X; 100X). Remaining crypts within ulcerated areas from cPLA2+/+ colons are indicated by arrows in the higher magnification image. (C) Representative images of Alcian blue-stained colons from the same mice shown in panel A (100X). (D) Spleen weights were measured before and after 7 days of DSS administration in both genotypes and the percent increase after DSS was calculated. (E and F) 3% DSS was administered for 4 or 7 days or plain drinking water was administered for 7 days to cPLA2+/+ and cPLA2−/− littermates and the expression of TNF and IL-1β was determined in colons by qRT-PCR for each group (n=4-5/group). *p<0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t-tests comparing cytokine expression between genotypes at the same time point of DSS exposure as indicated. (G) 3% DSS was administered in drinking water to cPLA2+/+ (n=20) and cPLA2−/− (n=20) littermates for 7 days followed by 7 days of plain water. Mice were weighed daily and weight change was reported as a percent relative to day 0. Data in all panels are means ± SEM.

To further investigate underlying mechanisms by which cPLA2 status may affect disease severity, cPLA2+/+ and cPLA2−/− mice were administered 3% DSS for 4 or 7 days or given plain drinking water for 7 days and colon tissue was isolated to determine the expression of two pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF and IL-1β. As shown in Figure 1E and F, cPLA2 deletion resulted in a significantly higher expression of TNF (2.8 ± 1.1 vs. 0.5 ± 0.1; P = 0.05) and IL-1β (0.7 ± 0.1 vs. 0.4 ± 0.1; P = 0.03) after 4 days of DSS exposure as compared to WT mice. To examine the effect of cPLA2 deletion on the recovery phase immediately following DSS-induced injury, mice were given 3% DSS for seven days followed by seven days of plain drinking water, and body weight change was evaluated. As shown in Figure 1G, although DSS exposure caused a more pronounced loss in body weight in cPLA2−/− mice during the seven days of DSS treatment, the recovery rate was unaffected by genotype.

3.2. cPLA2−/− mice have impaired colonic eicosanoid production

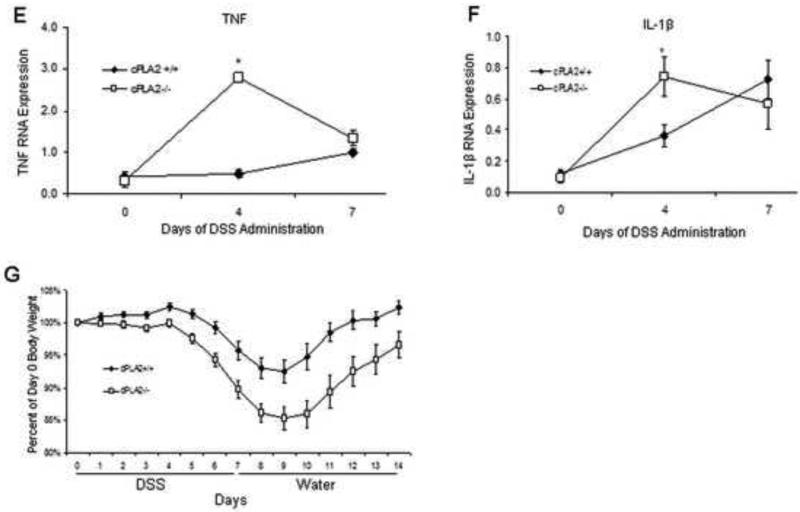

Given the importance of cPLA2 in regulating the synthesis of AA-derived eicosanoids, we next determined whether the more extensive mucosal injury in the KO mice might be associated with impaired formation of bioactive lipids. To test this possibility, WT and KO mice were given DSS (3%) for up to 7 days and colonic metabolite levels were measured. As shown in Figure 2 (A-H), DSS exposure to WT mice increased the levels of several metabolites to a varying extent at either 4 or 7 days. In the KO mice however, this increase was attenuated for PGE2, PGD2, 6-keto-PGF1α, PGF2α, TXB2 and 15-HETE at one or both time points with a similar trend for other metabolites. No leukotrienes were detected in colons from mice of either genotype.

Fig. 2.

Genetic deletion of cPLA2 diminishes colonic eicosanoid production. (A-H) 3% DSS was administered for 4 or 7 days or plain drinking water was administered for 7 days to cPLA2+/+ and cPLA2−/− mice and eicosanoid levels were measured in the colons using LC/MS (n=4/group). Data are means ± SEM and a p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t-tests comparing eicosanoid levels between genotypes at the same time point as indicated.

3.3. Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 results in greater susceptibility to DSS-induced colonic injury

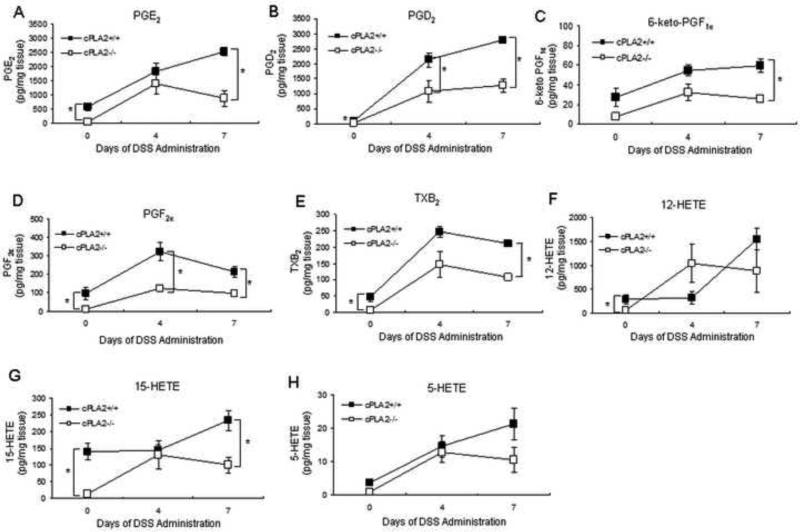

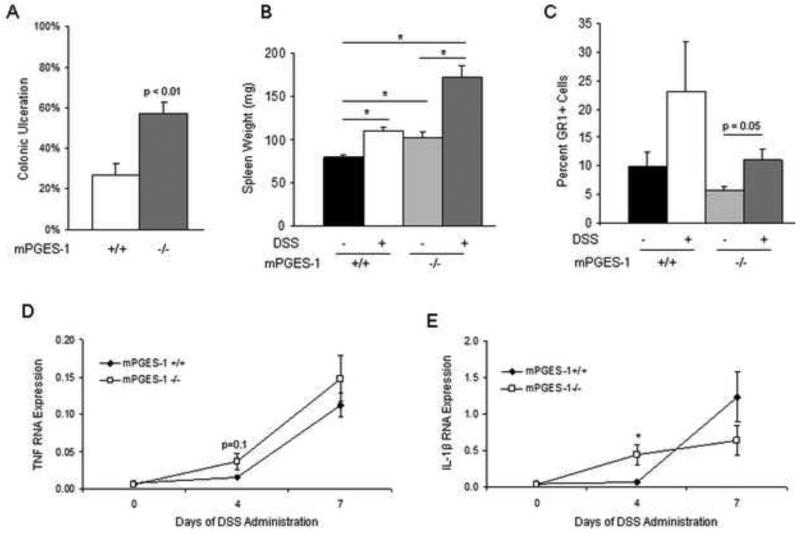

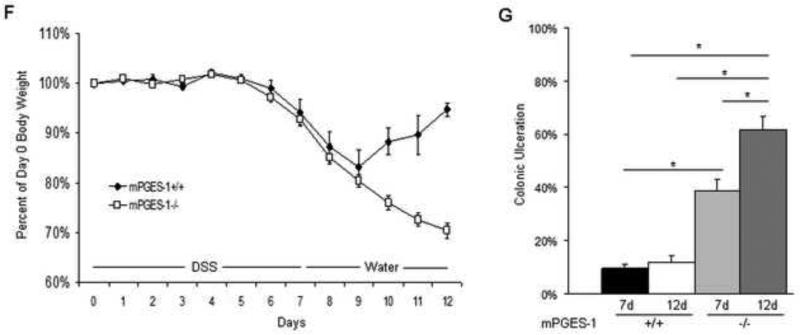

As described above, the majority of eicosanoid metabolites were reduced in the colons of cPLA2−/− mice (Fig. 2). However, given the important role of PGE2 in the maintenance of the intestinal mucosa [23], the following study was undertaken to evaluate its specific contribution to mucosal injury and repair. Mice with a genetic deletion of mPGES-1 (mPGES-1−/−), the terminal synthase for inducible PGE2 formation, and WT littermates were administered 3% DSS in the drinking water and disease severity was evaluated. As shown in Figure 3A, following 7 days of DSS treatment, mPGES-1 deletion enhanced acute colonic injury with ulcerated areas covering up to 60% of the length of the large intestine compared to more limited ulceration (~30%) in the WT mice. No ulcers were observed in untreated mPGES-1−/− mice. Additionally, mPGES-1−/− mice had a modestly greater increase in spleen weight compared to WT mice after DSS exposure (Fig. 3B). To gain further insight into the direct role of PGE2 on acute epithelial damage, the effects of mPGES-1 genotype on myeloid cell influx into the colonic LP after DSS administration was examined by FACS analysis. The Gr-1 positive cell population (a marker for neutrophils and macrophages) before and after DSS treatment in both genotypes was measured. As shown in Figure 3C, mPGES-1−/− mice had a significant increase in the percent of Gr-1 positive cells following DSS treatment. To further examine the inflammatory response, quantification of TNF and IL-1β expression was carried out and revealed a greater increase four days following DSS exposure in the PGES-1−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 3D and E). Examination of the small intestines after 7 days of DSS administration showed the presence of ulcerations mainly in the mucosa above the Peyer's patches (Supplementary Figure 2). A larger percentage of Peyer's patches had ulcerations above them in the knockout mice (7/9 vs. 3/9; p=0.069; n=4-5mice/group).

Fig. 3.

Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 is associated with more severe DSS-induced injury and impaired recovery. (A) 3% DSS was administered in drinking water to mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− (n=10) littermates for 7 days and the percentage of colonic ulceration was quantified in H&E-stained slides for each mouse and reported as an average. The p value was determined by an unpaired t-test. (B) Spleen weights were measured before and after 7 days of DSS administration in both genotypes. (C) The percent of GR-1 positive cells was quantified in the colonic LP isolated from mPGES-1+/+ and mPGES-1−/− mice under control conditions and after seven days of DSS administration (n=3/group). (D and E) Relative expression of TNF (D) and IL-1 β (E) was determined by qRT-PCR in the colons of control or 4 or 7 day DSS-exposed mPGES-1+/+ and mPGES-1−/− mice (n=4/group). (F) 2% DSS was administered in drinking water to mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− littermates (n=7) for 7 days, followed by plain drinking water for an additional 5 days. Weight change was reported as a percent change from day 0. (G) The extent of colonic ulceration was determined in H&E sections of colons from the same mice described in (F) and a separate group of mPGES-1+/+ (n=10) and mPGES-1−/− (n=8) littermates given 2% DSS for 7 days. Data represent the means ± SEM. *p<0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t-test as indicated.

We next determined the influence of inducible mPGES-1 activity on the recovery phase following acute intestinal injury. To investigate this, 2% DSS was given to mPGES-1+/+ and mPGES-1−/− mice for 7 days, followed by plain drinking water for 5 days. The percent of DSS was reduced in this experiment to limit the toxicity associated with higher concentrations in the mPGES-1−/− mice (Supplementary Table 1). As shown in Figure 3F, both mPGES-1−/− and mPGES-1+/+ mice exhibited progressive weight loss from days 4 through 9. While the mPGES-1+/+ mice began to recover by day 9, the mPGES-1−/− mice continued to lose weight over the next 5 days, suggesting either more extensive damage or delayed repair to the colonic mucosa. We next investigated the potential mechanism by which mPGES-1−/− mice had an inability to recover from DSS-induced injury by comparing the extent of mucosal injury in both mPGES-1 genotypes during the recovery phase after DSS exposure. Five days after removing DSS (“12d”), ulcers within the mPGES-1−/− colons continued to expand (up to 20%), while the extent of ulceration in WT mice remained the same (Fig. 3G). These data demonstrate that inducible PGE2 formation within the colon protects against acute injury as well as enhances recovery.

3.4. mPGES-1−/− mice have an altered colonic eicosanoid profile

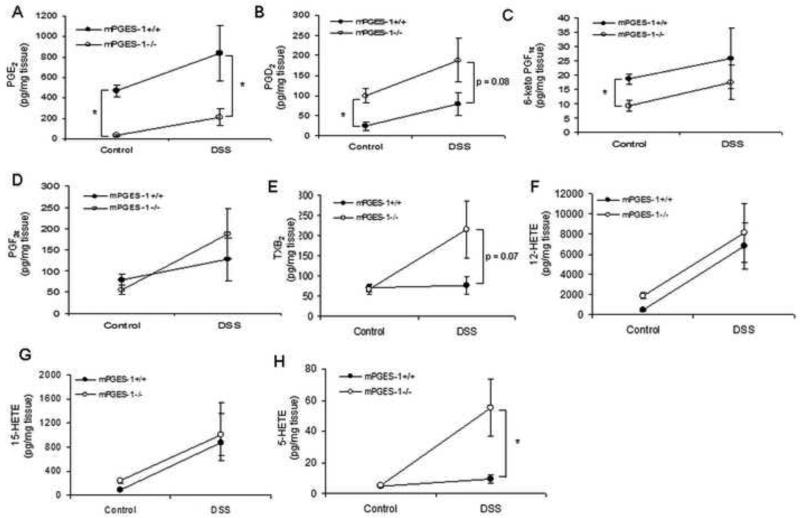

To confirm that genetic deletion of mPGES-1 specifically abrogates PGE2 formation within the colon and how that may affect the levels of other metabolites, a panel of eicosanoids were measured by LC/MS after administration of 3% DSS or plain drinking water for 7 days. As expected, PGE2 levels were reduced in the colon of the mPGES-1−/− mice, regardless of treatment (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, we observed a compensatory increase in the levels of PGD2 in mPGES-1−/− mice regardless of treatment as well as increases in TXB2 and 5-HETE only after DSS exposure, without major differences in other eicosanoids (Fig. 4B-H).

Fig. 4.

Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 alters colonic eicosanoid levels. (A-H) 3% DSS or plain drinking water was administered to mPGES-1+/+ and mPGES-1−/− (n = 4-5/group) for 7 days and eicosanoid levels were measured in the colons using LC/MS. Data are means ± SEM and a p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t-tests comparing eicosanoid levels between genotypes at the same time point as indicated.

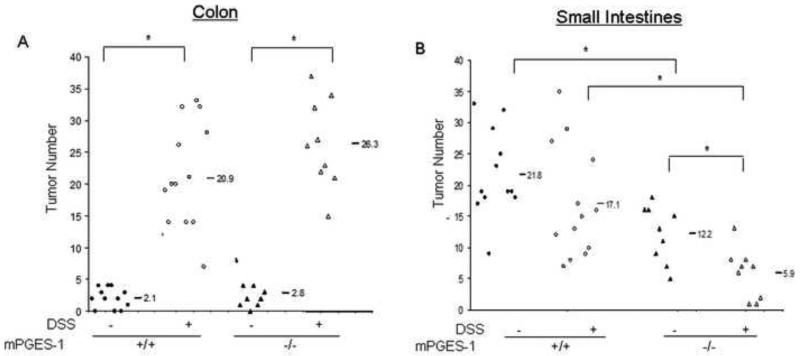

3.5. mPGES-1 deletion affords partial protection against DSS-induced tumor formation in ApcMin/+ mice

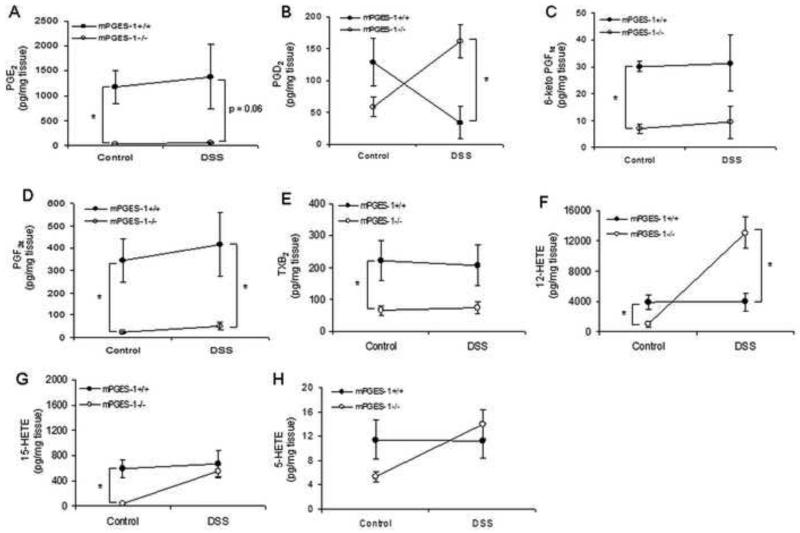

DSS has been used to enhance colon polyp formation in ApcMin/+ mice [35, 38]. In the following study, we determined whether the enhanced acute inflammation caused by mPGES-1 deletion and/or compensatory increase in other eicosanoids might ultimately impact upon the formation of intestinal polyps. Using an established protocol [35], five-week old ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− compound mutant mice were given 2% DSS for one week and then sacrificed four weeks later to evaluate tumor burden. As expected, body weight loss was more pronounced in the ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice upon DSS administration (Supplementary Figure 3) and both genotypes experienced rectal bleeding consistent with colitis. As shown in Figure 5A, DSS administration caused an approximately 10-fold increase in the number of colon tumors regardless of mPGES-1 genotype. In addition, DSS exposure caused a change in tumor morphology from the typically flat adenomas to a more pedunculated adenoma demonstrating high-grade dysplasia, which was unaffected by genotype. No evidence of tumor invasion was observed in any of the experimental groups. As predicted by our previous study[27], genetic deletion of mPGES-1 conferred protection against polyp development in the small intestines under control conditions. As shown in Figure 5B, polyp formation in the untreated ApcMin/+ mice was significantly reduced (21.8 ± 2.0 to 12.2 ± 1.5; P = 0.002) by mPGES-1 deletion. Interestingly, while DSS exposure had no significant effect on intestinal polyp number in ApcMin/+ mice, polyps were significantly reduced in the ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice (12.2 ± 1.5 to 5.9 ± 1.3, P = 0.006) after DSS administration (Fig. 5B). Histological examination of small intestinal polyps showed morphology of tubular adenomas in all groups (Supplementary Figure 4). Given that we observed a compensatory increase in PGD2 and other eicosanoids in the colons of mPGES-1−/− mice and that PGD2 has been shown to suppress intestinal tumorigenesis 28, we hypothesized that altered metabolite production in the small intestines of ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice may have contributed to the reduced tumor burden observed after DSS exposure. In order to test this idea, we utilized the mPGES-1−/− and wild-type mice described earlier in this study to measure the eicosanoid profile in the small intestines before and after 7 days of DSS exposure, as a surrogate for what changes might occur in the ApcMin/+ mice. We first measured PGE2 levels in the small intestines and confirmed that KO mice had reduced levels under control conditions as well as after 7 days of DSS exposure (Fig. 6A). Similar to what was observed in the colons of the mPGES-1−/− mice, PGD2 levels in the small intestines were markedly increased compared to wild-type littermates after DSS exposure (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, we also observed a compensatory increase in 12-HETE upon DSS administration and reduced levels of other COX-2 derived metabolites under either condition (Fig. 6). These data indicate that an altered eicosanoid profile in the small intestines as a result of mPGES-1 deletion, may suppress tumorigenesis in this model. Given that PGE2 can regulate β-catenin we tested whether mPGES-1 status impacted upon its nuclear localization or the presence of APC in polyp tissue. IHC analysis revealed that β-catenin localized to the nucleus and APC was lost in small intestinal polyps regardless of genotype (Supplementary Figure 4). We speculate that nuclear localization still occurred in the knockout mice because of the enhanced levels of PGD2 and possibly other eicosanoids found in these mice. PGD2 has been shown to increase β-catenin levels in another model of colitis-associated intestinal tumorigenesis [39].

Fig. 5.

DSS exposure reduces the number of small intestinal polyps in ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice. ApcMin/+ (n=14) and ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− (n=9) mice were given DSS for 1 week followed by 4 weeks of plain drinking water or plain water only for 5 weeks (ApcMin/+ (n=12)) (ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− (n=9)). The average number of polyps was enumerated in methylene blue-stained of whole mounts of colons (A) or small intestines (B). Each data point represents an individual mouse and the numbers indicate the mean value for each group. *p<0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t-test as indicated.

Fig. 6.

Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 alters small intestinal eicosanoid levels. (A-H) 3% DSS or plain drinking water was administered to mPGES-1+/+ and mPGES-1−/− (n = 4-5/group) for 7 days and eicosanoid levels were measured in the small intestines using LC/MS. Data are means ± SEM and a p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired t-tests comparing eicosanoid levels between genotypes at the same time point as indicated.

4. Discussion

IBD is associated with cyclical increases in PGs within the intestinal mucosa, mediated by the coordinated actions of enzymes within the AA cascade [9, 12, 14]. However, the role of PG metabolites at different stages of IBD pathogenesis and inflammation-associated tumorigenesis has not been fully clarified. In this study, we examined the requirement for PGs in the maintenance and repair of the intestinal epithelium following chemical-induced mucosal injury as well their role in inflammation-associated intestinal tumorigenesis.

PGs are important in maintaining GI homeostasis by contributing to the maintenance of mucosal integrity and limiting the inflammatory response [2, 7]. In the first phase of this study, we tested how the global reduction of eicosanoids impacts DSS-induced colonic injury by utilizing mice with a genetic deletion of cPLA2. Important to the goals of the present study, we have previously shown that the absence of cPLA2 causes a global reduction in AA metabolites within the intestinal tract, including but not limited to PGE2 [40]. Acute disease severity was markedly enhanced by the absence of cPLA2, associated with increased colonic ulceration, pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and exaggerated weight loss (Fig. 1). Although only the role of cPLA2 was examined in this study we cannot rule out the potential importance of other PLA2s including iPLA2 which has been shown to generate AA and impact upon cellular processes [41]. This concept is supported by the incomplete reduction of certain eicosanoids in the colons of cPLA2−/− mice in this study (Fig. 2).

In order to directly test the role of PGE2 on DSS-induced colonic injury, we utilized mice with a genetic deletion of mPGES-1, the terminal synthase for inducible PGE2 formation [42]. Consistent with the findings in cPLA2−/− mice, mPGES-1−/− mice sustained much more extensive mucosal injury compared to WT mice following DSS exposure (Fig. 3), which was associated with reduced PGE2 formation (Fig. 4A). In line with our findings, Morteau et al. and Ishikawa et al. showed that genetic deletion of COX-2, the inducible enzyme that converts AA to PGH2, resulted in greater susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis, associated with impaired PGE2 production [24, 25]. A subsequent study performed in mPGES-1−/− mice showed greater susceptibility to acute DSS-induced injury, indicating a specific protective role for PGE2 [23]. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that metabolic redirection of PGH2 as a result of mPGES-1 deletion may shift the metabolic balance of prostaglandin species, possibly contributing to the observed phenotype [43-46]. This possibility is highlighted by the observation that the basal levels of PGD2 were significantly higher (2.5-fold) in the colons of mPGES-1−/− mice compared to WT mice as well as having a trend for this effect after DSS exposure, suggesting metabolic redirection from the COX-2 metabolite, PGH2 (Fig. 4B). Previous studies utilizing mPGES-1−/− mice have also reported increased PGD2 production [47, 48]. Although there is evidence that exogenous PGE2 administration can attenuate DSS-induced damage [49], the effects of PGD2 treatment is unknown. We also examined levels of HETEs given that they have been shown to impact upon the inflammatory process [50] and 5-HETE in particular has been found to be elevated in mucosal biopsies from colitis patients[51]. Interestingly, 5-HETE was increased in the colons of mPGES-1−/− mice following DSS administration, an effect not observed in wild-type mice. It is interesting to note that this increase was observed only for 5-HETE and not for 12- or 15 HETE. We speculate that this resulted from loss of PGE2 in the knockout mice and a subsequent inability to elevate cyclic AMP, a mediator known to phosphorylate 5-lipoxygenase and enhance its activity [52]. Cyclic AMP does not act on 12- or 15-lipoxygenase in this manner, thus resulting in specific enhancement of 5-HETE.

In light of the enhanced intestinal inflammation induced by DSS in the mPGES-1−/− mice, we sought to determine how this background of increased inflammation might impact upon intestinal tumorigenesis. As predicted by our previous study [27], genetic deletion of mPGES-1 conferred protection to the small intestine in untreated ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 5B). However, no effect was seen on colonic tumor burden, which may have resulted from the lack of incidence of colon tumors in ApcMin/+ mice thus not allowing the effect of PGE2 loss to be observed in this organ site. Although DSS exposure had no effect on polyp number in the small intestines of ApcMin/+ mice, ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice had a significant reduction in the number of polyps following DSS administration (Fig. 5B). In the colon, however, mPGES-1 status had no effect on polyp numbers in APCMin/+ mice, regardless of DSS treatment (Fig. 5A). In a previous study published by Tanaka et al., DSS administration to ApcMin/+ mice was shown to increase polyp burden in the distal region of the small intestines whereas in other regions of the gut a reduced burden was observed [35]. Our results show that DSS exposure did not alter polyp burden in the small intestines, a discrepancy that may be explained by differences in microbiota or housing conditions in the two studies. Only a limited number of studies have directly examined the role of PGs in inflammation-associated intestinal tumorigenesis. In one study published by Ishikawa et al. [30], genetic deletion of COX-1 or COX-2 had no effect on tumor development in the AOM/DSS model, although COX-2 deletion did protect against tumor formation induced by repeated injections with AOM alone. It is possible that the increased colonic inflammation known to occur in COX-1 or COX-2 nullizygous mice after exposure to DSS [24, 25] counteracts any growth suppressing effects on tumors as a result of the loss of COX enzymes. Importantly, this point is supported by another study showing that administration of the COX inhibitor nimesulide suppressed adenoma formation only after completing AOM/DSS exposure [32]. Our results show no protection against DSS-induced colon tumor formation in mice with a genetic deletion of mPGES-1 which may be a result of the extensive inflammation that occurs in this organ site, masking any beneficial effects of mPGES-1 deletion (Supplementary Figure 5). However, in the small intestines where DSS-induced inflammation is less robust (Supplementary Figures 2 and 5), the effects of PGE2 loss on tumor burden were readily observed. DSS has been previously shown to induce markedly more inflammation in the colon compared to the small intestines [53, 54]. The reduction in tumors in the small intestines of ApcMin/+:mPGES-1−/− mice may have resulted from a compensatory increase in PGD2 in the small intestines upon DSS exposure, an effect that was not seen in WT mice (Fig. 6B). In fact, the tumor suppressive role of PGD2 has been highlighted by a study carried out by Park et al., in which genetic deletion of hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase in ApcMin/+ mice resulted in increased intestinal polyps [28]. Conversely, the same study showed that over-expression of the human form of the enzyme suppressed polyp burden[28]. Surprisingly, we also observed reduced levels of certain other PG metabolites in the mPGES-1−/− mice including PGF2α and TXB2, effects that may have contributed to the reduced tumor burden in the ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 6) [46, 55].

In summary, this study demonstrates an important role for AA metabolism in the maintenance of gastrointestinal homeostasis by showing that disruption in certain key enzymes renders mice more susceptible to experimental colitis. Furthermore, demonstration of the importance of PG metabolite balance during inflammation and inflammation-associated tumorigenesis shows how potential agents that could selectively target the production of specific PGs may impact upon the production of other metabolites and have physiological consequences.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Genetic deletion of cPLA2 resulted in more severe acute murine experimental colitis

cPLA2−/− mice have reduced levels of eicosanoids as compared to wild-type mice

Loss of mPGES-1 in mice resulted in more severe colitis and impaired recovery

mPGES-1−/− mice have altered eicosanoid levels compared to wild-types

DSS administration to APCMin/+;mPGES-1−/− mice reduced intestinal tumor burden

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01CA114635 to DWR].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stack E, DuBois RN. Regulation of cyclo-oxygenase-2. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;(15):787–800. doi: 10.1053/bega.2001.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dey I, Lejeune M, Chadee K. Prostaglandin E2 receptor distribution and function in the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;(149):611–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrer R, Moreno JJ. Role of eicosanoids on intestinal epithelial homeostasis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;(80):431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halter F, Tarnawski AS, Schmassmann A, Peskar BM. Cyclooxygenase 2-implications on maintenance of gastric mucosal integrity and ulcer healing: controversial issues and perspectives. Gut. 2001;(49):443–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenson WF. Prostaglandins and epithelial response to injury. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;(23):107–10. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3280143cb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace JL, Devchand PR. Emerging roles for cyclooxygenase-2 in gastrointestinal mucosal defense. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;(145):275–82.. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Mann JR, DuBois RN. The role of prostaglandins and other eicosanoids in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 2005;(128):1445–61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melgar S, Drmotova M, Rehnstrom E, Jansson L, Michaelsson E. Local production of chemokines and prostaglandin E2 in the acute, chronic and recovery phase of murine experimental colitis. Cytokine. 2006;(35):275–83.. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raab Y, Sundberg C, Hallgren R, Knutson L, Gerdin B. Mucosal synthesis and release of prostaglandin E2 from activated eosinophils and macrophages in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;(90):614–20.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rampton DS, Hawkey CJ. Prostaglandins and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1984;(25):1399–413. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.12.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharon P, Ligumsky M, Rachmilewitz D, Zor U. Role of prostaglandins in ulcerative colitis. Enhanced production during active disease and inhibition by sulfasalazine. Gastroenterology. 1978;(75):638–40.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiercinska-Drapalo A, Flisiak R, Prokopowicz D. Effects of ulcerative colitis activity on plasma and mucosal prostaglandin E2 concentration. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 1999;(58):159–65.. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(99)00032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita S. Studies on changes of colonic mucosal PGE2 levels and tissue localization in experimental colitis. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1993;(28):224–35.. doi: 10.1007/BF02779224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zifroni A, Treves AJ, Sachar DB, Rachmilewitz D. Prostanoid synthesis by cultured intestinal epithelial and mononuclear cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1983;(24):659–64.. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.7.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg DJ, Zhang J, Weinstock JV, Ismail HF, Earle KA, Alila H, et al. Rapid development of colitis in NSAID-treated IL-10-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;(123):1527–42. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.1231527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonner GF. Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with use of celecoxib. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;(96):1306–8.. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cipolla G, Crema F, Sacco S, Moro E, de Ponti F, Frigo G. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and inflammatory bowel disease: current perspectives. Pharmacol Res. 2002;(46):1–6.. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(02)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gornet JM, Hassani Z, Modiglian R, Lemann M. Exacerbation of Crohn's colitis with severe colonic hemorrhage in a patient on rofecoxib. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;(97):3209–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kefalakes H, Stylianides TJ, Amanakis G, Kolios G. Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: myth or reality? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;(65):963–70.. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0719-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurahara K, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Honda K, Yao T, Fujishima M. Clinical and endoscopic features of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced colonic ulcerations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;(96):473–80.. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuter BK, Asfaha S, Buret A, Sharkey KA, Wallace JL. Exacerbation of inflammation-associated colonic injury in rat through inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest. 1996;(98):2076–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI119013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh VP, Patil CS, Jain NK, Kulkarni SK. Aggravation of inflammatory bowel disease by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in rats. Pharmacology. 2004;(72):77–84.. doi: 10.1159/000079135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara S, Kamei D, Sasaki Y, Tanemoto A, Nakatani Y, Murakami M. Prostaglandin E synthases: Understanding their pathophysiological roles through mouse genetic models. Biochimie. 2010;(92):651–9.. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa TO, Oshima M, Herschman HR. Cox-2 deletion in myeloid and endothelial cells, but not in epithelial cells, exacerbates murine colitis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;(32):417–26.. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morteau O, Morham SG, Sellon R, Dieleman LA, Langenbach R, Smithies O, et al. Impaired mucosal defense to acute colonic injury in mice lacking cyclooxygenase-1 or cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest. 2000;(105):469–78.. doi: 10.1172/JCI6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakanishi M, Menoret A, Tanaka T, Miyamoto S, Montrose DC, Vella AT, et al. Selective PGE(2) suppression inhibits colon carcinogenesis and modifies local mucosal immunity. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;(4):1198–208. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi M, Montrose DC, Clark P, Nambiar PR, Belinsky GS, Claffey KP, et al. Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;(68):3251–9.. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JM, Kanaoka Y, Eguchi N, Aritake K, Grujic S, Materi AM, et al. Hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase suppresses intestinal adenomas in ApcMin/+ mice. Cancer Res. 2007;(67):881–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinha P, Clements VK, Fulton AM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;(67):4507–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishikawa TO, Herschman HR. Tumor formation in a mouse model of colitis-associated colon cancer does not require COX-1 or COX-2 expression. Carcinogenesis. 2010;(31):729–36.. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez Y, Sotolongo J, Breglio K, Conduah D, Chen A, Xu R, et al. The role of prostaglandin E2 (PGE 2) in toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated colitis-associated neoplasia. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;(10):82. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohno H, Suzuki R, Sugie S, Tanaka T. Suppression of colitis-related mouse colon carcinogenesis by a COX-2 inhibitor and PPAR ligands. BMC Cancer. 2005;(5):46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonventre JV, Huang Z, Taheri MR, O'Leary E, Li E, Moskowitz MA, et al. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature. 1997;(390):622–5.. doi: 10.1038/37635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uematsu S, Matsumoto M, Takeda K, Akira S. Lipopolysaccharide-dependent prostaglandin E(2) production is regulated by the glutathione-dependent prostaglandin E(2) synthase gene induced by the Toll-like receptor 4/MyD88/NF IL6 pathway. J Immunol. 2002;(168):5811–6.. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka T, Kohno H, Suzuki R, Hata K, Sugie S, Niho N, et al. Dextran sodium sulfate strongly promotes colorectal carcinogenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice: inflammatory stimuli by dextran sodium sulfate results in development of multiple colonic neoplasms. Int J Cancer. 2006;(118):25–34.. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gijon MA, Zarini S, Murphy RC. Biosynthesis of eicosanoids and transcellular metabolism of leukotrienes in murine bone marrow cells. J Lipid Res. 2007;(48):716–25.. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600508-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarini S, Gijon MA, Ransome AE, Murphy RC, Sala A. Transcellular biosynthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes in vivo during mouse peritoneal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;(106):8296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903851106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper HS, Everley L, Chang WC, Pfeiffer G, Lee B, Murthy S, et al. The role of mutant Apc in the development of dysplasia and cancer in the mouse model of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;(121):1407–16. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zamuner SR, Bak AW, Devchand PR, Wallace JL. Predisposition to colorectal cancer in rats with resolved colitis: role of cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin d2. Am J Pathol. 2005;(167):1293–300. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montrose DC, Kadaveru K, Ilsley JN, Root SH, Rajan TV, Ramesh M, et al. cPLA2 is protective against COX inhibitor-induced intestinal damage. Toxicol Sci. 2010;(117):122–32.. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez T, Moreno JJ. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2 through arachidonic acid mobilization is involved in Caco-2 cell growth. J Cell Physiol. 2002;(193):293–8.. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park JY, Pillinger MH, Abramson SB. Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and secretion: the role of PGE2 synthases. Clin Immunol. 2006;119:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins D, Hogan AM, Skelly MM, Baird AW, Winter DC. Cyclic AMP-mediated chloride secretion is induced by prostaglandin F2alpha in human isolated colon. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;(158):1771–6.. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duffield-Lillico AJ, Boyle JO, Zhou XK, Ghosh A, Butala GS, Subbaramaiah K, et al. Levels of prostaglandin E metabolite and leukotriene E(4) are increased in the urine of smokers: evidence that celecoxib shunts arachidonic acid into the 5-lipoxygenase pathway. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;(2):322–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qualtrough D, Kaidi A, Chell S, Jabbour HN, Williams AC, Paraskeva C. Prostaglandin F(2alpha) stimulates motility and invasion in colorectal tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2007;(121):734–40.. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai CS, Luo SF, Ning CC, Lin CL, Jiang MC, Liao CF. Acetylsalicylic acid regulates MMP-2 activity and inhibits colorectal invasion of murine B16F0 melanoma cells in C57BL/6J mice: effects of prostaglandin F(2)alpha. Biomed Pharmacother. 2009;(63):522–7.. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.07.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elander N, Ungerback J, Olsson H, Uematsu S, Akira S, Soderkvist P. Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 accelerates intestinal tumorigenesis in APC(Min/+) mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;(372):249–53.. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monrad SU, Kojima F, Kapoor M, Kuan EL, Sarkar S, Randolph GJ, et al. Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 abolishes PGE2 production in murine dendritic cells and alters the cytokine profile, but does not affect maturation or migration. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;(84):113–21.. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tessner TG, Cohn SM, Schloemann S, Stenson WF. Prostaglandins prevent decreased epithelial cell proliferation associated with dextran sodium sulfate injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 1998;(115):874–82.. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moreno JJ. New aspects of the role of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids in cell growth and cancer development. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;(77):1–10.. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masoodi M, Pearl DS, Eiden M, Shute JK, Brown JF, Calder PC, et al. Altered colonic mucosal Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA) derived lipid mediators in ulcerative colitis: new insight into relationship with disease activity and pathophysiology. PLoS One. 2013;(8):e76532.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo M, Jones SM, Flamand N, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Phosphorylation by protein kinase a inhibits nuclear import of 5-lipoxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2005;(280):40609–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iizasa H, Genda N, Kitano T, Tomita M, Nishihara K, Hayashi M, et al. Altered expression and function of P-glycoprotein in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. J Pharm Sci. 2003;(92):569–76.. doi: 10.1002/jps.10326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawauchi S, Nakamura T, Miki I, Inoue J, Hamaguchi T, Tanahashi T, et al. Downregulation of CYP3A and P-glycoprotein in the secondary inflammatory response of mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis and its contribution to cyclosporine A blood concentrations. J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;(124):180–91.. doi: 10.1254/jphs.13141fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacoby RF, Marshall DJ, Newton MA, Novakovic K, Tutsch K, Cole CE, et al. Chemoprevention of spontaneous intestinal adenomas in the Apc Min mouse model by the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug piroxicam. Cancer Res. 1996;(56):710–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.