Abstract

AIM: To evaluate/isolate cancer stem cells (CSCs) from tissue or cell lines according to various definitions and cell surface markers.

METHODS: Lectin microarray analysis was conducted on CSC-like fractions of the human pancreatic cancer cell line Panc1 by establishing anti-cancer drug-resistant cells. Changes in glycan structure of CSC-like cells were also investigated in sphere-forming cells as well as in CSC fractions obtained from overexpression of CD24 and CD44.

RESULTS: Several types of fucosylation were increased under these conditions, and the expression of fucosylation regulatory genes such as fucosyltransferases, GDP-fucose synthetic enzymes, and GDP-fucose transporters were dramatically enhanced in CSC-like cells. These changes were significant in gemcitabine-resistant cells and sphere cells of a human pancreatic cancer cell line, Panc1. However, downregulation of cellular fucosylation by knockdown of the GDP-fucose transporter did not alter gemcitabine resistance, indicating that increased cellular fucosylation is a result of CSC-like transformation.

CONCLUSION: Fucosylation might be a biomarker of CSC-like cells in pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Anti-cancer drug resistance, Cancer stem cells, Fucosylation, Glycosylation, Pancreatic cancer, Sphere formation

Core tip: Fucosylation is one of the most important glycosylation events involved in cancer and inflammation. In the present study, we investigated oligosaccharide modifications in pancreatic cancer cancer stem cell (CSC)-like cells. Using several models of CSC-like cells, we found that fucosylation is a common type of glycosylation change in pancreatic cancer CSC-like cells. CSCs are known to be preferentially resistant to many current therapies, including various chemotherapeutic agents and radiation treatment. Our present study suggests that the identification of fucosylated glycoproteins derived from pancreatic cancer cells could lead to novel biomarker development for anticancer drug resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Increasing evidence indicates that many tumors are composed of significant functionally and morphologically heterogeneous cells. Tumor initiation and selected growth are driven by a small subset of cancer stem cells (CSCs) or tumor-initiating cells that give rise to a large population of differentiated progeny, and comprise the bulk of tumors[1,2]. Several lines of research indicate that CSCs are preferentially resistant to many current therapies, including various chemotherapeutic agents and radiation treatment[3,4]. Therapeutic strategies that effectively target CSCs could significantly impact patient survival. Recent progress in CSC research includes advances in isolation methods, markers, and biologic functions of CSCs. CSCs exhibit the following general biologic characteristics: slow and asymmetric growth, anti-cancer drug resistance, increased tumorigenicity in immunodeficient mice, and sphere formation.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with an overall five-year survival rate of only 1%-4%, and a median survival period of 4-6 mo[5,6]. It is usually diagnosed at a late stage with metastasis and is resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. CSCs of pancreatic cancer were reported to appear at the chronic pancreatitis stage, and the detection of CSCs at this stage can help overcome pancreatic cancer completely[7].

Glycans are branched oligosaccharide moieties that often become attached to proteins and lipids, and are then structurally and functionally modified. Because glycan structures differ among cell types, glycans can considered as the characteristic face of the cell. Recently, we reported that sialylated glycans are useful markers for CSC-like cells in hepatoma cell lines[8]. CSC-like fractions, isolated using a combination of CD133 antibody and Sambucus sieboldiana agglutinin lectin, showed higher tumorigenicity in athymic mice, greater spheroid formation ability, and resistance to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment[8]. Therefore, it appears that sialylation is a characteristic glycan modification for CSC-like cells of hepatoma cells. The biologic functions of oligosaccharides, however, differ in various cancer types. For example, although increased N-glycan branching by N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V plays a pivotal role in cancer metastasis and high expression is associated with poor prognosis in some cancers[9-11], it is a favorable prognosis marker in other cancers[12]. Thus, characteristic glycan structures for CSC-like cells could differ among various cancer types.

In the present study, we performed lectin microarray analysis on CSC-like fractions of the human pancreatic cancer cell line Panc1 by establishing anti-cancer drug-resistant cells in order to examine the characteristic glycan structures of CSC-like cells in pancreatic cancers. Changes in glycan structure of CSC-like cells were also investigated in sphere-forming cells as well as in CSC fractions obtained from overexpression of CD24 and CD44, which are conventional CSC markers for pancreatic cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Pancreatic cancer cell lines, Panc1, MIA PaCa-2, PSN-1, Capan-1, and BxPC-3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, United States). A pancreatic cancer cell line, PK59 was purchased from RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). All cell lines except Capan-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in humidified air. Capan-1 cell line was cultivated with Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Gibco of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) supplemented with 20% FBS and the same antibiotics. To establish gemcitabine-resistant Panc1 cells, the cells were treated step-wise with 1-200 ng/mL gemcitabine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 mo, and the resulting gemcitabine-resistant Panc1 cells were named Panc1-RG. Parental Panc1 cells were also cultured for the same period without gemcitabine, and designated as Panc1-P. In the case of short-term gemcitabine treatment in five pancreatic cancer cell lines (PK59, MIA PaCa-2, PSN-1, Capan-1, and BxPC-3), the cells were incubated with IC50 gemcitabine (in the case of PK59, 1 μg/mL) for 2 d.

Lectin microarray

Total patterns of oligosaccharide structures in Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells were investigated using evanescent-field fluorescence-assisted lectin microarray. Forty-five kinds of lectin were immobilized on a glass slide in triplicate. This procedure has been previously described in detail by Kuno et al[13].

Lectin blotting and Western blotting

Cells were harvested from culture dishes in PBS. After precipitation by centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, cells were suspended in TNE buffer [10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 1% NP40, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA] containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and then placed on ice for 30 min to allow for solubilization. Samples were centrifuged at 20000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were collected. Cell lysates were quantitated using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ten micrograms of total cellular protein were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions, and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States). After blocking with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin overnight at 4 °C, the membrane was incubated with biotinylated Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL; J-Oil Mills, Tokyo, Japan) or Aspergillus oryzae lectin (AOL; unbiotinylated [Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan], biotinylated with the Biotin Labeling Kit-NH2, [DOJINDO Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan]). The membrane was washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 7.4) and incubated with diluted avidin-peroxidase conjugates (ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, United States). Signals were detected using RX-U X-ray film (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the ReliaPrep RNA Cell Miniprep System (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, United States). The RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically, and samples were then stored at -80 °C until use. RNA samples (500 ng) were reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT), dNTPs, and RNaseOUT (Invitrogen of Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cDNA was then diluted five-fold and specific PCR product amplification was performed with SYBR Premix Ex TaqII (TAKARA Bio, Shiga, Japan). Primers were used at 625 nmol/L each in a 20-μL reaction volume. The cycle parameters were: denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, and 40 cycles composed of 15-s denaturation at 95 °C, 10-s annealing at 59 °C, and 25-s polymerization at 72 °C. Total RNA from each sample was analyzed in triplicate for each target RNA in separate wells. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a Mx3000P Real-Time QPCR System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Primer sequences used in this study are provided in Table 1. Expression levels of the genes of interest were normalized to ribosomal protein L4 and calculated based on the ΔΔCT method[14]. The results are expressed relative to those of Panc1-P as control.

Table 1.

Primer and shRNA sequences for the genes examined in the present study

| Genes | Analysis | 5'-Sequence-3' |

| FUT1 | RT-PCR | F: AGACTTTGCCCTGCTCACAC |

| R: TGAAGTTGGCCAGGTAGACAG | ||

| FUT2 | RT-PCR | F: CAGATGCCTTTCTCCTTTCC |

| R: ACTCCCACATGGCTTGAATC | ||

| FUT3 | RT-PCR | F: CTGGATCTGGTTCAACTTGG |

| R: CGGTAGGACATGGTGAGATTG | ||

| FUT4 | RT-PCR | F: GGGTTTGGATGAACTTCGAG |

| R: AGCCATAAGGCACAAAGACG | ||

| FUT8 | RT-PCR | F: ATCCTGATGCCTCTGCAAAC |

| R: GGGTTGGTGAGCATAAATGG | ||

| GMDS | RT-PCR | F: TGGAGGCTATGTGGTTGATG |

| R: CAAATTCCCGGACACTATGG | ||

| FX | RT-PCR | F: ACACGTCATCCATCTTGCTG |

| R: AGGACGTTGTCGTTCATGTG | ||

| SLC35C1 | RT-PCR | F: GGTGTGGCCTTCTACAATGTG |

| R: ATGATGATACCGCAGGTGAG | ||

| HNF4α | RT-PCR | F: CATCTTCTTTGACCCAGATGC |

| R: CGTTGATGTAGTCCTCCAAGC | ||

| IL-6 | RT-PCR | F: ATGCAATAACCACCCCTGAC |

| R: GCGCAGAATGAGATGAGTTG | ||

| RPL4 | RT-PCR | F: GACTTAACACACGAGGAGATGC |

| R: GCATGCTGTGCACATTTAGG | ||

| FUT1 | shRNA | GGTAATCAGATGGGACAGTAT |

| Negative control | shRNA | GGAATCTCATTCGATGCATAC |

| SLC35C1 | shRNA | CUACUUAUAGACCCAAUCATT |

| Negative control | shRNA | UCUUAAUCGCGUAUAAGGCTT |

Sphere formation assay

Panc1 and PSN-1 cells were seeded on 10 cm culture dishes (AGC Techno Glass, Tokyo, Japan) and cultured in serum-free medium consisting of DMEM⁄F-12 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, United States), B27 (Invitrogen), 5 μg/mL insulin, and 2.75 μg/mL transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich). Sphere cells were passaged every 3 d. Sphere cells cultured for 6 d were collected and analyzed. Sphere cell-forming ability was calculated with the BZ Analyzer II software equipped with fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Briefly, 5 × 105 pancreatic cancer cells were seeded in 60 mm culture dishes and after 3 d culture, the area of the formed sphere colonies were estimated in each cell line.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested with PBS containing 0.5 mmol/L EDTA and fixed with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) for 20 min on ice. The cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled AAL, Pholiota squarrosa lectin (PhoSL, J-Oil Mills), or Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA-l, J-Oil Mills) for lectin flow cytometry analyses. To investigate the expression of CSC markers, Panc1 cells were incubated with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human CD24 (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Germany) and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human CD44 (BD Biosciences) in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 20 min on ice. Isotype-matched mouse IgG (BD Biosciences) was used as a control. Cells were washed three times with PBS, and flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer operated with CellQuestPro software version 5.2, (BD Biosciences). Ten thousand events were acquired in each sample. For FACS cell sorting, 5-10 × 106 living cells were stained with anti-human CD24 and CD44 antibodies, and then sorted using FACSAria II (BD Biosciences). Doublet cells were eliminated using FSC-A/FSC-H and SSC-A/SSC-H. Dead cells were also excluded by gating staining with 7-amino-actinomycin D (BD Biosciences).

RNA interference

For FUT1 knockdown, an expression vector carrying small hairpin RNA (shRNA) against human FUT1 was purchased from Qiagen (Venlo, Limburg, Netherlands), and transfected into Panc1-RG cells with NEON Transfection System (Invitrogen). At 24 h, the medium was changed to complete medium with Hygromycin B (Invitrogen) at 500 μg/mL for selection. To knock down the GDP-fucose transporter gene, Panc1-RG cells were transfected with shRNA against SLC35C1 via retroviral introduction. Small interfering oligonucleotides specific for SLC35C1 were designed using an online design tool (Takara Bio). The oligonucleotides were annealed and then ligated into the BamHI/ClaI sites of the pSINsi-hU6 DNA vector (Takara Bio). Retroviral supernatant was obtained by transfection into human embryonic kidney 293T cells, using a Retrovirus Packaging Kit Ampho (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Panc1-RG cells were infected with the viral supernatant, and the cells were then selected with 5 μg/mL puromycin for 2-3 wk to obtain stable transfectant cells.

Cell survival assay

Cell growth was assessed by the WST-8 assay (2-[2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl]-3-[4-nitrophenyl]-5-[2,4-disulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 10 μL of WST-8 reagent was added to the cells in each well and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. After incubation, sample absorbance was determined using an iMark Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan) at 450 nm.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for interleukin-6

Panc1 cells [Panc1-P, Panc1-RG, monolayer cells (same as Panc1-P), and sphere cells] were seeded at a density of 2.4 × 105 cells/60 mm culture dish, and cultivated in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin or in sphere conditioned medium (described in sphere formation assay). After 48 h, the supernatants were collected and interleukin (IL)-6 levels were quantified using Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay system (SRL Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The IL-6 concentrations were normalized to cell number at the time of collection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP Pro 10.0 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The results are expressed as mean ± SD. Groups of data were compared by the Wilcoxon test for non-parametric data. Differences were considered statistically significant for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Gemcitabine-resistant Panc1-RG cells are enriched with CSC-like cells

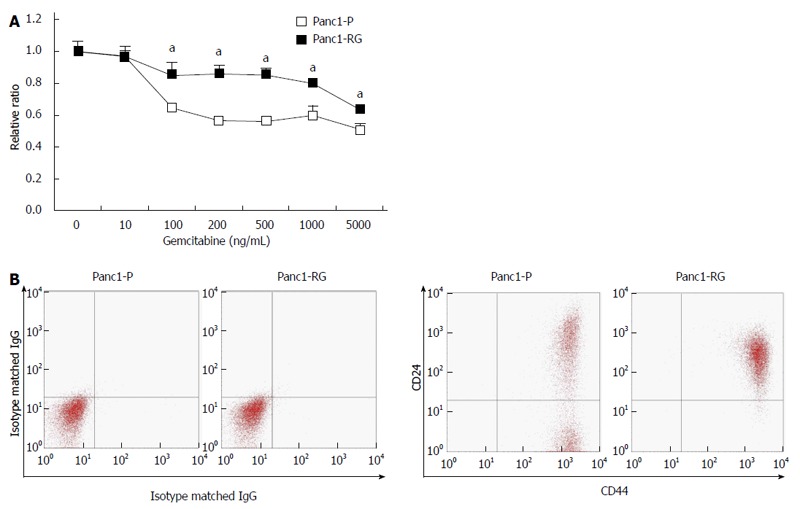

By exposing Panc1 cells stepwise to increasing gemcitabine concentrations over 5 mo, we established gemcitabine-resistant Panc1 cells, (Panc1-RG). Panc1-RG cells were 37.5-fold more resistant to gemcitabine treatment compared with Panc1-P cells [Figure 1A; 25% inhibitory concentration (IC25) values: 80 and 3000 ng/mL for Panc1-P and Panc1-RG, respectively]. Next, we performed flow cytometry analysis to investigate whether CSC markers for pancreatic cancer are increased on the Panc1-RG cell surface. In general, CD24 and CD44 are often used as cell surface markers of pancreatic CSC fractions. As expected, Panc1-RG cells exhibited an increased population of CD24+/CD44+ cells (98.30%) compared with Panc1-P cells (56.40%; Figure 1B). These results indicate that CSC-like cells are enriched in Panc1-RG cells following long-term gemcitabine treatment.

Figure 1.

Cancer stem cells are enriched in established gemcitabine-resistant cells. A: Panc1-RG cells were established by long-term step-wise gemcitabine treatment. WST assay showed that Panc1-RG cells exhibited gemcitabine resistance compared with Panc1-P cells; B: Flow cytometric analysis showing a higher ratio of CD24+/CD44+ cells in Panc1-RG cells compared with Panc1-P cells. All results are expressed as mean ± SD; aP < 0.05 vs Panc1-P cells.

Identification of characteristic glycan structure in Panc1-RG cells

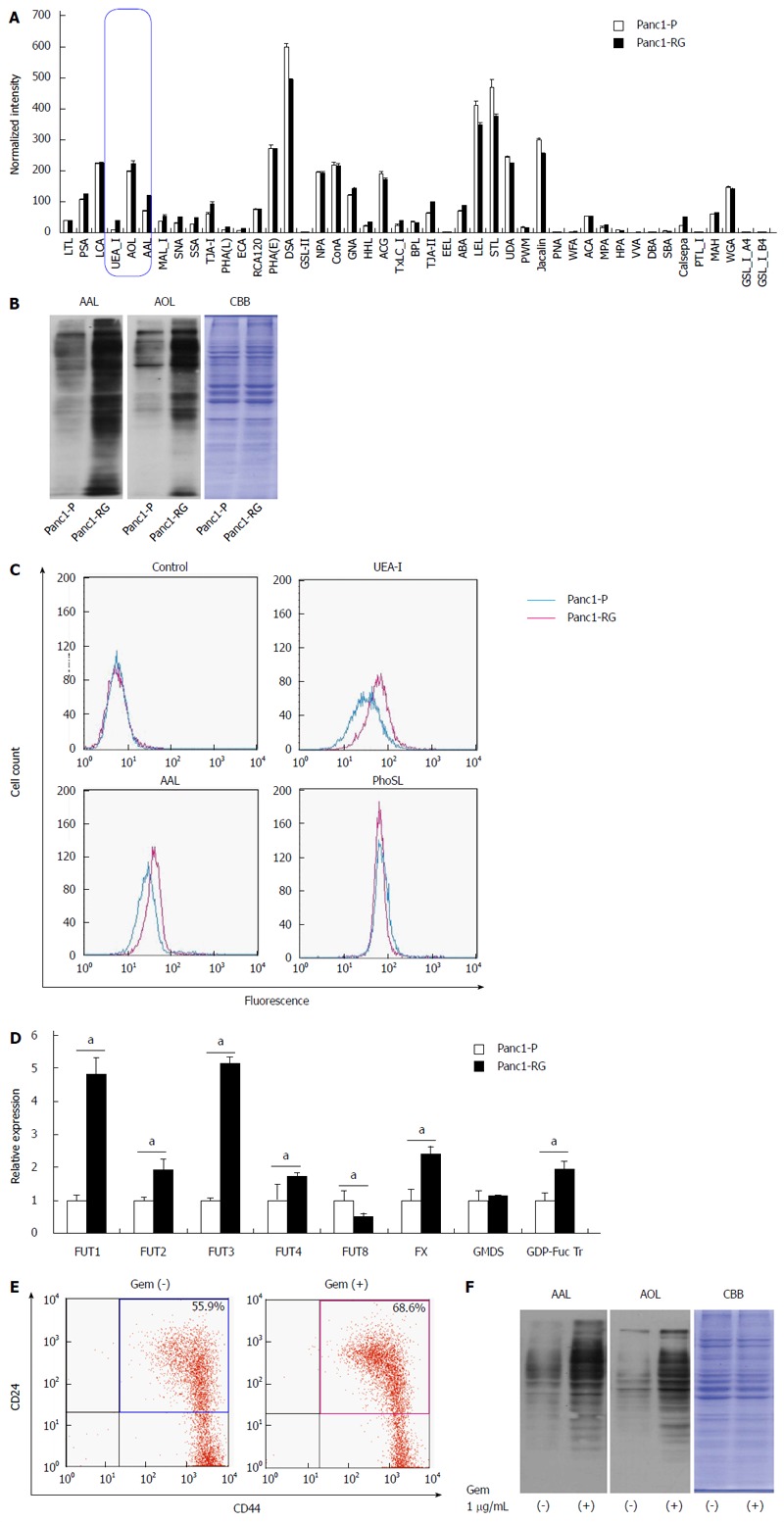

To determine glycan structures unique to Panc1-RG cells, lectin microarray analysis was performed (Figure 2A). Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells exhibited several differences in lectin binding; in particular, three fucosylated glycan-recognizing lectins (UEA-I, AAL, AOL) showed substantially higher intensities in Panc1-RG than in Panc1-P cells. UEA-I specifically recognizes α1,2-fucosylation, AAL recognizes all types of fucosylation such as α1,2, α1,3/α1,4 and α1,6 linkages, and AOL recognizes α1,2- and α1,6-fucosylation[15]. Lectin blot analyses using AAL or AOL also revealed increased cellular fucosylation in Panc1-RG cells (Figure 2B). Furthermore, flow cytometric analysis showed increased cell surface expression of fucosylated proteins recognized by UEA-I and AAL lectins, but not PhoSL lectin, which recognizes α1,6-fucosylated glycans[16]. These results indicate an increase in α1,2- and α1,3-/α1,4-fucosylation, but not in α1,6-fucosylation, in Panc1-RG cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Fucosylation is enhanced in gemcitabine-treated pancreatic cancer cells. A: Differential glycan profiles of Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells were analyzed by lectin microarray. The fluorescence intensity of each lectin was normalized to the intensity of wheat germ agglutinin; B: Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) or Aspergillus oryzae lectin (AOL) lectin blot of Panc1-P and Panc1-RG. Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining confirms equal protein loading among lanes; C: Cell-surface fucosylated glycoproteins in Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells were assessed by flow cytometry using Ulex europaeus agglutinin (UEA)-I, AAL, and Pholiota squarrosa lectin (PhoSL) lectins; D: Fucosylation-related gene expression, determined by real-time reverse transcription PCR in Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells, and expressed relative to that of Panc1-P cells; E: Flow cytometric analysis represented gemcitabine treatment increased the ratio of CD24+/CD44+ cells in PK59 cells; F: AAL or AOL lectin blot of PK59 cells with (+) or without (-) gemcitabine treatment. All results are expressed as mean ± SD; aP < 0.05 vs Panc1-P cells.

To investigate the role of various regulatory factors in the increased fucosylation, we compared the mRNA expression levels of GDP-mannose-4,6-dehydratase, FX, GDP-fucose transporter (GDP-Fuc Tr), fucosyltransferase (FUT) 1, FUT2, FUT3, FUT4, and FUT8 between Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells by real-time RT-PCR analysis (Figure 2D). FUT1, FUT2, FUT3, FUT4, FX, and GDP-Fuc Tr expression levels in Panc1-RG cells were significantly higher than those in Panc1-P cells (Ps < 0.05). These results corroborate the results of lectin blot analysis and lectin flow cytometry, as FUT1 and FUT3 catalyze the formation of α1,2 and α1,3/α1,4 linkages, respectively. Moreover, FX and GDP-Fuc Tr increase the amount of GDP-Fuc substrate in the Golgi apparatus.

We established Panc1-RG cells for long-term gemcitabine treatment and this cell line contained more CSC like cells than Panc1-P. However, Hermann et al[17] showed short-term gemcitabine treatment also works in CSC-like cells concentration. Therefore, we analyzed the fucosylation status in other cell lines such as PK59, MIA PaCa-2, PSN-1, Capan-1, and BxPC-3, which were treated with gemcitabine for a short time. Expectedly, we found that short-term gemcitabine treatment also caused concentration of CSC-like cells and enhanced fucosylation in mutliple cell lines. Representative results in PK59 cells are shown in Figure 2E and F.

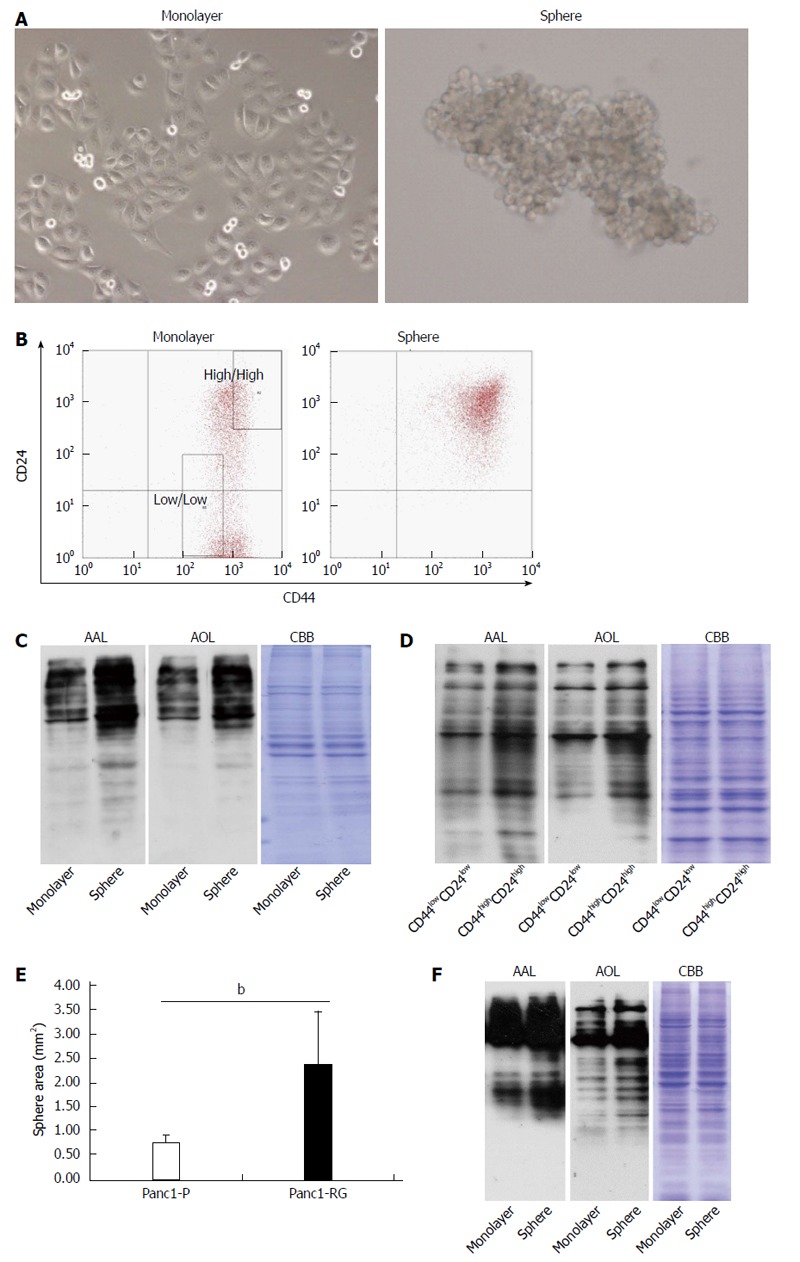

Sphere-forming cells and CD24high/CD44high cancer stem-like cells from Panc1-P showed high expression of fucosylated glycans

Because numerous studies demonstrated that the formation of spheres in serum-free medium is one of the characteristics of CSCs[17,18], Panc1-P cells were cultured under stem cell-selective conditions. After 6 d, Panc1 cells aggregated into floating spheroid clusters (Figure 3A). To examine CD24 and CD44 expression in sphere and monolayer cells, we performed flow cytometry analysis. A larger CD24+/CD44+ population was observed in sphere cells (97.13%) compared with monolayer cells (54.93%). Subsequently, we performed western blot analysis using AAL or AOL lectins to examine whether fucosylated glycans were increased in sphere cells. Increased binding to both lectins was observed in sphere cells as compared with monolayer cells (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the expression pattern of fucosylation regulatory genes in sphere cells was similar to that seen in Panc1-RG cells (data not shown). It is already known that CSC markers for pancreatic cancer, such as CD24 and CD44, regulate cellular behavior[19,20]. To evaluate the relationship between the extent of fucosylation and CD24 and CD44 expression, we further studied cellular fucosylation in the CD24high/CD44high fraction, and compared this with the CD24low/CD44low fraction. The region of each fraction is indicated in the Figure 3B “monolayer”. The CD24high/CD44high fraction exhibited higher cellular fucosylation than the CD24low/CD44low fraction (Figure 3D). These results indicate increased fucosylation in cancer stem-like phenotype cells.

Figure 3.

Fucosylation is enhanced in cancer stem cell-like cells fractions of pancreatic cancer cells. A: Phase-contrast images of monolayer (left panel) and sphere cells (right panel) derived from Panc1 cells; B: Results of flow cytometric analysis in monolayer and sphere Panc1 cells using CD24 and CD44 antibodies. CD24+/CD44+ cells were increased in sphere cells compared with monolayer cells; C: Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) or Aspergillus oryzae lectin (AOL) lectin blot of monolayer and sphere Panc1 cells; D: AAL or AOL lectin blot of CD24high/CD44high or CD24low/CD44low Panc1 cells obtained by cell sorting. Each region is indicated as a square field in (B); E: Comparison of sphere cell-forming ability between Panc1-P and Panc1-RG; F: AAL or AOL lectin blot of monolayer and PSN-1 cells. Results are expressed as mean ± SD; bP < 0.01 vs Panc1-P cells. CBB: Coomassie brilliant blue.

Panc1-RG cells contained more CSC like cells than parental Panc1-P cells (Figure 1B). This observation suggests that Panc1-RG forms more sphere colonies than Panc1-P. To clarify this possibility in Panc1-RG, we performed sphere-forming assay using Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells. We found sphere formation was significantly increased in Panc1-RG compared with in Panc1-P (P < 0.01) (Figure 3E).

Next, we investigated whether or not sphere formation enhances cellular fucosylation in other pancreatic cancer cell lines (PK59, MIA PaCa-2, PSN-1, Capan-1, and BxPC-3). Among these cell lines, sphere formation was observed only in PSN-1 cells, and we confirmed fucosylation was increased in sphere formation of PSN-1 cells (Figure 3F).

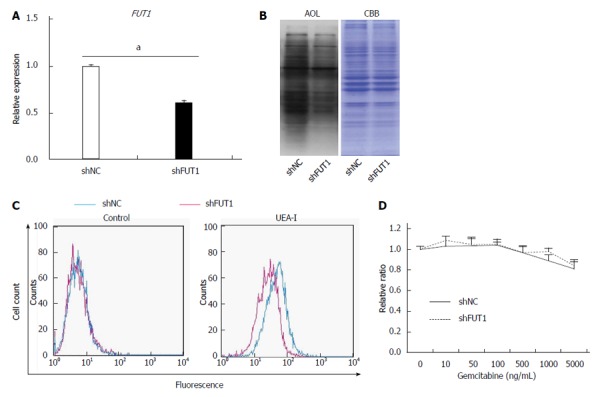

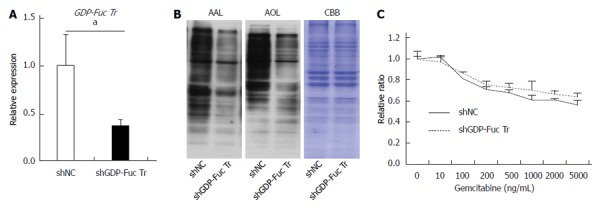

Fucosylation does not directly contribute to gemcitabine resistance

Previously, Cordel et al[21] reported that FUT1 is associated with 5-FU resistance in rat colon cancer cells. To examine whether or not α1,2-fucosylation by FUT1 is involved in gemcitabine resistance in Panc1 cells, shRNA against FUT1 was transfected into Panc1-RG cells and stable transfectants were selected with hygromycin B. The shFUT1 transfectants exhibited an approximately 30% decrease in FUT1 mRNA expression compared with the shRNA-negative control (Figure 4A). α1,2-fucosylation levels were lower in shFUT1-transfected Panc1-RG cells, as evidenced by AOL lectin blot as well as UEA-I flow cytometry (Figure 4B and C). However, there was no change in gemcitabine resistance among these cells (Figure 4D). Next, to investigate whether total cellular fucosylation is directly involved in gemcitabine resistance, GDP-Fuc Tr, a key regulator of cellular fucosylation, was knocked down in Panc1-RG cells[22]. The shRNA transfectants showed significantly decreased GDP-Fuc Tr mRNA expression compared to negative control (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A). Cellular fucosylation also decreased dramatically in shRNA transfectant cells, as evidenced by lectin blot analyses using AAL or AOL lectins (Figure 5B). However, decreased fucosylation had no effect on gemcitabine sensitivity (Figure 5C). In other words, cellular fucosylation does not directly contribute to gemcitabine resistance in Panc1 cells; increased fucosylation is merely a marker for CSC-like cells in pancreatic cancer.

Figure 4.

FUT1 knockdown in Panc1-RG cells does not alter gemcitabine resistance. A: Expression of fucosyltransferase (FUT)1 mRNA in Panc1-RG cells stably expressing small hairpin (sh)RNA; B: Aspergillus oryzae lectin (AOL) blot of shNC- or shFUT1-expressing Panc1-RG cells; C: Flow cytometric analysis using Ulex europaeus agglutinin (UEA)-I; D: WST assay results of transfectant cells treated with various gemcitabine concentrations. Results are expressed as mean ± SD; aP < 0.05 vs shNC. CBB: Coomassie brilliant blue; NC: Negative control.

Figure 5.

GDP-fucose transporter gene knockdown does not affect gemcitabine resistance in Panc1-RG cells. A: Expression of GDP-fucose transporter (GDP-Fuc Tr) mRNA in small hairpin (sh)RNA-expressing Panc1-RG cells; B: Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) or Aspergillus oryzae lectin (AOL) blots for shRNA transfectant cells; C: WST assay results for cells treated with various gemcitabine concentrations. Results are expressed as mean ± SD; aP < 0.05 vs shNC. CBB: Coomassie brilliant blue; NC: Negative control.

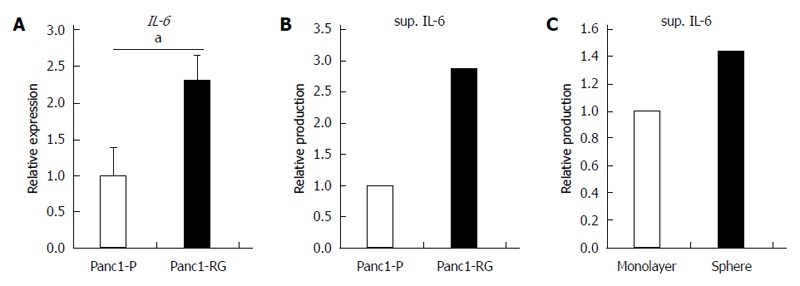

Panc1-RG cells secreted higher levels of IL-6, compared to Panc1-P cells

In this study, we found that fucosylation was increased under several CSC-like cell transformation conditions. Some bioactive substances are related to the increased fucosylation in CSC-like cells. Previously, we reported that IL-6 treatment of human hepatoma cell lines increased fucosylation with a marked increase in fucosylation regulatory genes[23]. Therefore, we also investigated the IL-6 production between Panc1-P and Panc1-RG cells in this study. Expression of IL-6 mRNA was significantly higher in Panc1-RG than that in Panc1-P (P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). The concentration of IL-6 in conditioned media from Panc1-RG cultures was also substantially higher than that from Panc1-P (Figure 6B). In addition, the concentration of IL-6 in conditioned media from sphere Panc1-P cells was also higher than those from monolayer Panc1-P cells (Figure 6C). These results indicate that both anti-cancer drug resistance and sphere formation enhanced IL-6 production in Panc1-P cells.

Figure 6.

Increased interleukin-6 production in anti-cancer drug-resistance and sphere-forming cells. A: Expression of interleukin (IL)-6 mRNA was measured by real-time reverse transcription PCR in Panc1-P and Panc1-RG; B: The concentration of IL-6 in conditioned media from Panc1-P or Panc1-RG cultures was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA); C: The concentration of IL-6 in conditioned media from monolayer or sphere-forming Panc1-P cells was measured by ELISA. All results are expressed as mean ± SD; aP < 0.05 vs Panc1-P cells.

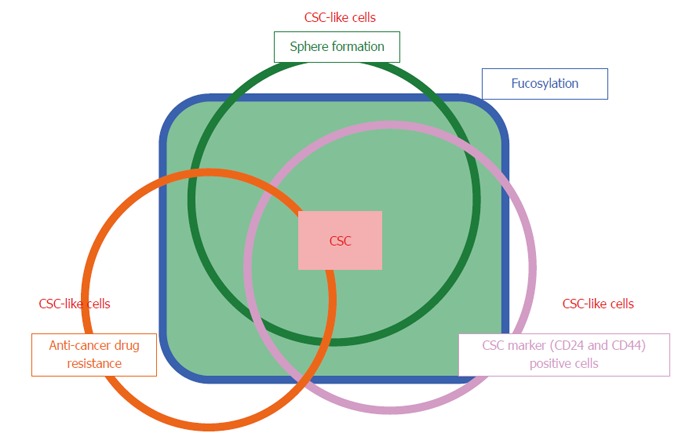

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that fucosylation is a common glycosylation marker for three cancer stem cell-like phenotypes: gemcitabine-resistant cells, sphere-forming cells, and CD24high/CD44high CSC fractions. Specifically, gemcitabine-resistant cells and sphere-forming cells exhibited very similar fucosylation patterns. In our present study, the fucosylation patterns varied, likely dependent on the differing conditions of cells in culture. The protein expression patterns were also different in each condition. Although α1-2- and α1-3/1-4-fucosylation increased, α1-6-fucosylation did not change upon downregulation of FUT8 expression and upregulation of FX and GDP-Fuc Tr genes. These results suggest that CSC-like cells, similar to sphere-forming cells, were condensed during long-term exposure to gemcitabine. Induced pluripotent cells and embryonic stem cells have been shown to exhibit increased α1-2-fucosylation and decreased α1-6-fucosylation[24]. Although α1-6-fucosylation was unchanged in Panc1-RG cells compared with Panc1-P cells, FUT8 knockdown in Panc1-RG cells decreased α1-6-fucosylation, accompanied by a slight enhancement in gemcitabine resistance (data not shown).

Next, we investigated whether other types of fucosylation are directly involved in gemcitabine resistance. Downregulation of α1-2-fucosylation in Panc1-RG cells using shFUT1 RNA did not alter gemcitabine resistance. This result is inconsistent with the observation that FUT1 is involved in 5-FU resistance in rat colon cancer cell lines[21]. This might be due to differences between cancer cell lines and/or anti-cancer agents. Our insufficient FUT1 knockdown efficiency, in spite of repeated attempts, might have caused the discrepancy in gemcitabine resistance. Therefore, we focused on GDP-Fuc Tr, the most important regulatory factor for all types of fucosylation[22].

GDP-Fuc Tr was reduced to approximately 1/4 of its original expression level; this resulted in a dramatic decrease in total cellular fucosylation, but no change in gemcitabine resistance. This indicates that fucosylation does not directly contribute to gemcitabine resistance, and might be merely a marker for pancreatic cancer CSC-like cells. The molecular mechanisms underlying increased fucosylation in Panc1-RG cells remain unknown. Recently, Lauc et al[25] reported that hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)1α and its downstream molecule HNF4α are master transcription factors controlling cellular fucosylation. High HNF4α mRNA expression was observed in Panc1-RG cells compared with Panc1-P cells (data not shown). IL-6 production in pancreatic cancer has been associated with cancer aggressiveness and poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer[26,27]. We previously reported that treatment of human hepatoma cell lines with IL-6 caused a marked increase in fucosylation regulatory genes[23]. Interestingly, secreted IL-6 levels as well as IL-6 mRNA levels were significantly higher in Panc1-RG cells than in Panc1-P cells. These results strongly suggest that long-term stimulation with high-dose IL-6 induces increasing fucosylation in Panc1-RG cells. Yamada et al[28] showed that IL-6 is involved in resistance to anticancer drugs. These findings suggest that IL-6 plays pivotal and independent roles in increased cellular fucosylation and gemcitabine resistance. Taken together, increased cellular fucosylation is a common glycan change in three CSC-like phenotypes in pancreatic cancer (Figure 7), and the identification of fucosylated glycoproteins derived from pancreatic cancer cells could lead to novel biomarker development for anticancer drug resistance.

Figure 7.

Overview of the relationship between fucosylation and three types of cancer stem cell-like cells. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a limited fraction of cancer cells, which show asymmetric and slow growth, anti-cancer drug resistance, and sphere formation. CSC-like cells are differentiated from and have similar biologic characteristics of CSCs. Fucosylation is common type of glycosylation in the CSC-like phenotype of pancreatic cancer under various conditions.

COMMENTS

Background

Fucosylation is one of the most important glycosylation events involved in cancer and inflammation.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In the present study, authors investigated oligosaccharide modifications in pancreatic cancer cancer stem cell (CSC)-like cells. Using several models of CSC-like cells, they found that fucosylation is a common type of glycosylation change in pancreatic cancer CSC-like cells.

Applications

CSCs are known to be preferentially resistant to many current therapies, including various chemotherapeutic agents and radiation treatment. The present study suggests that the identification of fucosylated glycoproteins derived from pancreatic cancer cells could lead to novel biomarker development for anticancer drug resistance.

Peer-review

The manuscript reported an interesting finding that fucosylation is a common oligosaccharide modification in pancreatic cancer CSC-like cells, and increased cellular fucosylation is correlated with drug (such as gemcitabine) resistance. Therefore, the identification of fucosylated glycoproteins derived from pancreatic cancer cells could lead to novel biomarker development for anticancer drug resistance. Overall, the experiments were well done and properly interpreted.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A; No. 21249038) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and partially supported as a research program of the Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P-Direct), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: August 4, 2014

First decision: August 27, 2014

Article in press: December 1, 2014

P- Reviewer: Bazhin AV, Li CY S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ailles LE, Weissman IL. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4741–4751. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim GP, Sargent DJ, Mahoney MR, Rowland KM, Philip PA, Mitchell E, Mathews AP, Fitch TR, Goldberg RM, Alberts SR, et al. Phase III noninferiority trial comparing irinotecan with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma previously treated with fluorouracil: N9841. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2848–2854. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell PJ, Yachida S, Mudie LJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, Stebbings LA, Morsberger LA, Latimer C, McLaren S, Lin ML, et al. The patterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature09460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moriwaki K, Okudo K, Haraguchi N, Takeishi S, Sawaki H, Narimatsu H, Tanemura M, Ishii H, Mori M, Miyoshi E. Combination use of anti-CD133 antibody and SSA lectin can effectively enrich cells with high tumorigenicity. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1164–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murata K, Miyoshi E, Kameyama M, Ishikawa O, Kabuto T, Sasaki Y, Hiratsuka M, Ohigashi H, Ishiguro S, Ito S, et al. Expression of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V in colorectal cancer correlates with metastasis and poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1772–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui SF, Pawelek J, Handerson T, Lin CY, Dickson RB, Rimm DL, Camp RL. Coexpression of beta1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V glycoprotein substrates defines aggressive breast cancers with poor outcome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2517–2523. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto E, Ino K, Miyoshi E, Shibata K, Takahashi N, Kajiyama H, Nawa A, Nomura S, Nagasaka T, Kikkawa F. Expression of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V in endometrial cancer correlates with poor prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1538–1544. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dosaka-Akita H, Miyoshi E, Suzuki O, Itoh T, Katoh H, Taniguchi N. Expression of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase v is associated with prognosis and histology in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1773–1779. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuno A, Uchiyama N, Koseki-Kuno S, Ebe Y, Takashima S, Yamada M, Hirabayashi J. Evanescent-field fluorescence-assisted lectin microarray: a new strategy for glycan profiling. Nat Methods. 2005;2:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nmeth803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumura K, Higashida K, Ishida H, Hata Y, Yamamoto K, Shigeta M, Mizuno-Horikawa Y, Wang X, Miyoshi E, Gu J, et al. Carbohydrate binding specificity of a fucose-specific lectin from Aspergillus oryzae: a novel probe for core fucose. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15700–15708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi Y, Tateno H, Dohra H, Moriwaki K, Miyoshi E, Hirabayashi J, Kawagishi H. A novel core fucose-specific lectin from the mushroom Pholiota squarrosa. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33973–33982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, Bruns CJ, Heeschen C. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang X, Zheng P, Tang J, Liu Y. CD24: from A to Z. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7:100–103. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagano O, Okazaki S, Saya H. Redox regulation in stem-like cancer cells by CD44 variant isoforms. Oncogene. 2013;32:5191–5198. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordel S, Goupille C, Hallouin F, Meflah K, Le Pendu J. Role for alpha1,2-fucosyltransferase and histo-blood group antigen H type 2 in resistance of rat colon carcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:142–148. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000101)85:1<142::aid-ijc24>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriwaki K, Noda K, Nakagawa T, Asahi M, Yoshihara H, Taniguchi N, Hayashi N, Miyoshi E. A high expression of GDP-fucose transporter in hepatocellular carcinoma is a key factor for increases in fucosylation. Glycobiology. 2007;17:1311–1320. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narisada M, Kawamoto S, Kuwamoto K, Moriwaki K, Nakagawa T, Matsumoto H, Asahi M, Koyama N, Miyoshi E. Identification of an inducible factor secreted by pancreatic cancer cell lines that stimulates the production of fucosylated haptoglobin in hepatoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:792–796. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tateno H, Toyota M, Saito S, Onuma Y, Ito Y, Hiemori K, Fukumura M, Matsushima A, Nakanishi M, Ohnuma K, et al. Glycome diagnosis of human induced pluripotent stem cells using lectin microarray. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:20345–20353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauc G, Essafi A, Huffman JE, Hayward C, Knežević A, Kattla JJ, Polašek O, Gornik O, Vitart V, Abrahams JL, et al. Genomics meets glycomics-the first GWAS study of human N-Glycome identifies HNF1α as a master regulator of plasma protein fucosylation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lesina M, Kurkowski MU, Ludes K, Rose-John S, Treiber M, Klöppel G, Yoshimura A, Reindl W, Sipos B, Akira S, et al. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitsunaga S, Ikeda M, Shimizu S, Ohno I, Furuse J, Inagaki M, Higashi S, Kato H, Terao K, Ochiai A. Serum levels of IL-6 and IL-1β can predict the efficacy of gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2063–2069. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada D, Kobayashi S, Wada H, Kawamoto K, Marubashi S, Eguchi H, Ishii H, Nagano H, Doki Y, Mori M. Role of crosstalk between interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance in biliary tract cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1725–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]