Abstract

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a multi-system disease characterized by the formation of thromboembolic complications and/or pregnancy morbidity, and with persistently increased titers of antiphospholipid antibodies. We report the case of a 50-year-old, previously healthy man who presented with fever and new-onset, dull abdominal pain. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed segmental small bowel obstruction, for which an emergency laparotomy was performed. Histopathologic examination of resected tissues revealed multiple intestinal and mesenteric thromboses of small vessels. Laboratory tests for serum antiphospholipid (anticardiolipin IgM) and anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies were positive. Despite proactive implementation of anticoagulation, steroid, and antibiotic therapies, the patient’s condition rapidly deteriorated, and he died 22 d after admission. This case highlights that antiphospholipid syndrome should be suspected in patients with unexplainable ischemic bowel and intestinal necrosis presenting with insidious clinical features that may be secondary to the disease, as early diagnosis is critical to implement timely treatments in order to ameliorate the disease course.

Keywords: Anticardiolipin antibodies, Antiphospholipid syndrome, Intestinal necrosis, Mesenteric arteriolar thrombosis, Small bowel obstruction

Core tip: Antiphospholipid syndrome is a multi-organ disease characterized by the presence of thromboembolic complications and/or pregnancy morbidity, and with persistently increased titers of antiphospholipid antibodies. This case report demonstrates that antiphospholipid syndrome should be suspected for cases of unexplainable ischemic bowel and intestinal necrosis with insidious clinical features that may be secondary to the disease, as early diagnosis is critical to amelioration of the disease course.

INTRODUCTION

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by thrombotic microangiopathy, recurrent fetal loss, and moderate thrombocytopenia[1]. APS can affect any organ system, thus the manifestations vary greatly[2]. Hepatic manifestations, such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, small hepatic vein thrombosis, infarction (spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, intestine, etc.), ascites, esophageal perforation, and ischemic colitis, are often caused by vascular occlusion[1,3]. However, abdominal manifestations of APS are rare, representing only 1.5% of APS cases[3]. In this report, we describe an unusual case of segmental small bowel necrosis with insidious onset and atypical clinical features that may have been secondary to APS.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old, previously healthy man was admitted to our hospital due to fever, dull left lower quadrant pain, and vomiting that had persisted for four days. The fever had first developed three months earlier, reaching 39.0 °C, and was resolved with antibiotics. The patient worked as a driver and denied alcohol abuse and addiction to drugs, but had a 30-year history of cigarette smoking. He had no family history of autoimmune diseases.

Upon physical examination, the patient had a blood pressure of 210/62 mmHg, 124 beats/min pulse rate, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min, and body temperature of 38.6 °C. The abdomen was soft and mildly tender in the left lower abdomen without organomegaly or abnormal masses. Bowel sounds were hypoactive. There was no malar rash, livedo reticularis, or cardiac murmurs. Laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 22.1 × 109/L with 92% neutrophils, 127 g/L hemoglobin, and a platelet count of 52 × 109/L. His liver enzyme levels, creatinine, uric acid, amylase, lipase, electrolytes, coagulation tests, protein C, protein S and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory tests were within normal ranges.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed segmental dilated small bowel loops with wall thickening and contrast weakening, which indicated small bowel necrosis (Figure 1). No intestinal perforation or thrombosis was observed in the mesenteric arteries. The patient’s working diagnosis was thus considered as segmental small bowel obstruction and necrosis, and an emergency laparotomy was performed. The superior and inferior mesenteric and celiac arteries appeared normal and pulsatile, however, a 20 cm section of the small bowel that was 60 cm from the ligament of Treitz was entirely necrotic (Figure 2). The necrotic segment was resected, and an end-to-end anastomosis of the small bowel was performed. Histologic examination of resected tissues revealed extensive intestinal and mesenteric mucosal necrosis, congestion, and multiple small vessel thromboses (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen indicated segmental dilated small bowel loops with wall thickening and contrast weakening.

Figure 2.

Gross appearance of resected necrotic small bowel.

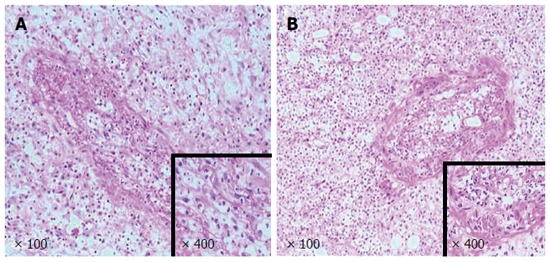

Figure 3.

Pathologic findings. Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed necrosis of the mucosae, congestion, and thrombosis of small vessels in the small bowel (A) and mesentery (B).

The patient was administered piperacillin and tazobactam postoperatively, and remained stable for six days after surgery. The hemogram improved with a leukocyte count of 9.9 × 109/L with 90.3% neutrophils, 103 g/L hemoglobin, and a platelet count of 128 × 109/L. However, the fever returned on day 10 after surgery, and further laboratory tests showed an increased leukocyte count of 27.3 × 109/L with 89.6% neutrophils, 96 g/L hemoglobin, and a platelet count of 121 × 109/L. The antibiotic treatment was supplemented with levofloxacin, and samples were sent to test for lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid antibodies. The patient’s fever was not reduced despite the addition of imipenem from day 14 through 17 after surgery. Results of the antibody tests indicated elevated IgM-anticardiolipin titers at 54 MPU (normal range: < 5 MPU) and anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies at 35 U/mL (positive > 15 U/mL), whereas the lupus anticoagulant was within the normal limit. Treatment with intravenous heparin and methylprednisolone was then given. However, on day 19 after the surgery, the patient developed a cough with expectoration, and a CT scan indicated severe pulmonary infection and hydropericardium (Figure 4). At this time, the blood tests showed a leukocyte count of 0.9 × 109/L with 36.2% neutrophils, 52 g/L hemoglobin, and a platelet count of 47 × 109/L; the sputum culture was positive for Acinetobacter baumannii. The patient was then transferred to the intensive care unit, but died of respiratory failure on day 22 after the surgery. No post-mortem examination was conducted.

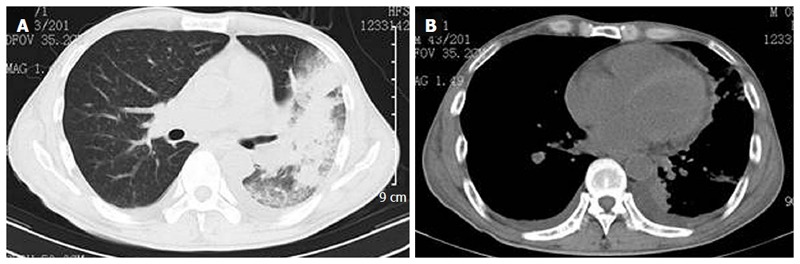

Figure 4.

Radiologic findings. Computed tomography showed characteristics of pulmonary infection (A) and hydropericardium (B).

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis for APS is based on the presence of at least one clinical and one laboratory criterion according to the Sapporo statement[4-7], and requires the presence of vascular thrombosis or fetal loss/premature birth associated with a positive lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin or anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies. For a positive diagnosis, laboratory tests must be verified after at least 12 wk. Catastrophic APS is the most severe form of the disease, for which the diagnostic criteria include multiple-organ system involvement, aggravation of manifestations within a week, small vessel occlusion in at least one organ or tissue, and presence of antiphospholipid antibodies[8]. As the patient in the case reported here did not survive past 12 wk, a definitive diagnosis of APS could not be obtained. However, the available clinical and laboratory evidence and the rapid progression of the patient’s condition indicate APS. Moreover, multiple organs were involved (small bowel, lung, and heart), indicating a fulminant form of APS. A biopsy was not obtained from the lung because of the patient’s rapid deterioration.

Bowel involvement is the second most frequently observed condition in APS with abdominal manifestation[9]. Although visceral ischemia occurs from arterial thrombosis in APS, only a few cases of intestinal ischemia have been described in detail[2,10-16]. Consequently, the incidence of ischemic bowel and infarction in APS is likely underestimated. Intestinal ischemia results from reduced flow in the superior and inferior mesenteric and celiac arteries, caused by emboli, atherosclerotic obstruction, thrombosis, or vasospasm. CT is considered a first-line investigation in APS patients with abdominal symptoms[17], which revealed no sign of thrombosis in the large vessels of our patient, but rather segmental small bowel obstruction and necrosis. An emergency laparotomy indicated that the underlying cause for the obstruction was thromboses in the small vessels of the intestine and mesentery, which is typical in cases of APS[18,19]. Moreover, other possible etiologies for thrombosis were excluded (Table 1).

Table 1.

Possible etiology for thrombosis

| Description | Cause |

| I. Injury of vascular endothelial cells | Mechanical (atherosclerosis), chemical (medication), or biologic (endotoxin) |

| II. Increase in platelet amount and activity | Thrombocytosis, injuries caused by mechanical, chemical, or immune factors |

| III. Increased blood coagulation | Pregnancy, advanced age, trauma, or tumor |

| IV. Decreased anticoagulant activity | Decreased antithrombin, protein C, S, or vitamin B12 deficiency, hyperhomocysteinemia |

| V. Decrease of fibrinolytic activities | Abnormality of plasminogen activator release or increased inhibition |

| VI. Abnormality of hemorheology | Hyperfibrinogenemia, hyperlipidemia, dehydration, or polycythemia |

Treatment of APS, which includes anticoagulants and corticosteroids, was administered to our patient at an advanced stage, and thus did not provide significant improvement. Recent expert recommendations suggest that plasma exchange should be initiated in patients with catastrophic APS who do not respond well to these treatments[20]. However, our patient’s circulatory condition precluded plasma exchange. The insidious onset of thrombosis combined with mild clinical symptoms delayed a diagnosis of APS[12,21], which may have facilitated further progression of vascular occlusion and organ involvement.

The presentation of venous or arterial intestinal thromboses can be non-specific, thus a high index of suspicion is needed for any signs of abdominal involvement in similar cases. In the case presented here, we believe that the dull abdominal pain and fever were due to bowel ischemia that was secondary to APS. Subsequently, the patient developed segmental small bowel necrosis, pulmonary infection, and hydropericardium. This case report highlights that a high level of suspicion for APS is required when patients present with unexplained abdominal pain and fever, as early diagnosis is critical to slow the course of the disease.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 50-year-old, previously healthy man, presented with fever, dull left lower quadrant pain, and vomiting that had persisted for four days.

Clinical diagnosis

The abdomen was soft and mildly tender in the left lower abdomen and bowel sounds were hypoactive.

Differential diagnosis

Appendicitis; gastrointestinal tumor; ileus.

Laboratory diagnosis

WBC, 22.1 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 127 g/L; platelet count, 52 × 109/L; liver enzyme level, creatinine, uric acid, amylase, lipase, electrolytes, coagulation tests and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory tests were within normal range.

Imaging diagnosis

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen indicated segmental dilated small bowel loops with wall thickening and contrast weakening.

Pathological diagnosis

Histologic examination of resected tissues revealed extensive intestinal and mesenteric mucosal necrosis, congestion, and multiple thromboses in the small vessels.

Treatment

The patient was treated with anticoagulation, steroids, and antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam, levofloxacin, and imipenem).

Related reports

Gastrointestinal manifestations are observed in only 1.5% of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) cases.

Term explanation

Acinetobacter baumannii is an emerging nosocomial pathogen that is responsible for infection outbreaks worldwide.

Experiences and lessons

Unexplainable ischemic bowel and intestinal necrosis with insidious clinical features may be secondary to APS, and therefore a high level of suspicion is required, as early diagnosis may ameliorate the course of the disease.

Peer-review

This article suggests that APS should be suspected in cases presenting with unexplained abdominal symptoms, including ischemic bowel and intestinal necrosis.

Footnotes

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethical review committee of Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s relatives.

Conflict-of-interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: September 7, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Article in press: January 16, 2015

P- Reviewer: Ciccocioppo R, Watanabe T, Yen HH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmeyer C, Barrier A, Frazier A, Fulgencio JP, Lecomte I, Grateau G, Callard P. Diffuse large and small bowel necrosis in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1011–1014. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000230085.45674.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, Khamashta MA, Shoenfeld Y, Camps MT, Jacobsen S, Lakos G, Tincani A, Kontopoulou-Griva I, Galeazzi M, Meroni PL, Derksen RH, de Groot PG, Gromnica-Ihle E, Baleva M, Mosca M, Bombardieri S, Houssiau F, Gris JC, Quéré I, Hachulla E, Vasconcelos C, Roch B, Fernández-Nebro A, Boffa MC, Hughes GR, Ingelmo M; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019–1027. doi: 10.1002/art.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, Lockshin MD, Branch DW, Piette JC, Brey R, Derksen R, Harris EN, Hughes GR, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1309–1311. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1309::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, Derksen RH, DE Groot PG, Koike T, Meroni PL, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim W, Crowther MA, Eikelboom JW. Management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;295:1050–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, Greer IA, Greaves M; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, Erkan D, Boffa MC, Piette JC, Khamashta MA, Shoenfeld Y; Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Project Group. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12:530–534. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu394oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uthman I, Khamashta M. The abdominal manifestations of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1641–1647. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asherson RA, Mackworth-Young CG, Harris EN, Gharavi AE, Hughes GR. Multiple venous and arterial thromboses associated with the lupus anticoagulant and antibodies to cardiolipin in the absence of SLE. Rheumatol Int. 1985;5:91–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00270303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asherson RA, Morgan SH, Harris EN, Gharavi AE, Krausz T, Hughes GR. Arterial occlusion causing large bowel infarction--a reflection of clotting diathesis in SLE. Clin Rheumatol. 1986;5:102–106. doi: 10.1007/BF02030977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sánchez-Guerrero J, Reyes E, Alarcón-Segovia D. Primary antiphospholipid syndrome as a cause of intestinal infarction. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:623–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappell MS, Mikhail N, Gujral N. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage and intestinal ischemia associated with anticardiolipin antibodies. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1359–1364. doi: 10.1007/BF02093805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel YI, St John A, McHugh NJ. Antiphospholipid syndrome with proliferative vasculopathy and bowel infarction. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:108–110. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi BG, Jeon HS, Lee SO, Yoo WH, Lee ST, Ahn DS. Primary antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with abdominal angina and splenic infarction. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22:119–121. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson SC, Willis J, Wong RC. Ischemic colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and the lupus anticoagulant: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:257–260. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Si-Hoe CK, Thng CH, Chee SG, Teo EK, Chng HH. Abdominal computed tomography in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:284–289. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greisman SG, Thayaparan RS, Godwin TA, Lockshin MD. Occlusive vasculopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Association with anticardiolipin antibody. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, Lie JT, Burcoglu A, Lim K, Muñoz-Rodríguez FJ, Levy RA, Boué F, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Clinical and laboratory features of 50 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1998;77:195–207. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199805000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim W. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:675–680. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saji M, Nakajima A, Sendo W, Tanaka M, Koseki Y, Ichikawa N, Harigai M, Akama H, Taniguchi A, Terai C, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome with complete abdominal aorta occlusion and chondritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2001;11:159–161. doi: 10.3109/s101650170030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]