Abstract

Background and Objectives

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is responsible for devastating nosocomial infections among severely burn patients. Class C of cephalosporinase (AmpC-β-lactamases) is important cause of multiple β-lactam resistance in P. aeruginosa. The aim of this study was to detect the AmpC-β-lactamases producing isolates among carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolated from burn patient.

Material and Methods

a total of 100 isolates of carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolates from different burn patients were investigated. Three phenotypic methods were selected for identification of the AmpC-β-lactamases producing isolates.

Results

Fifty four isolates were AmpC producer as detected by AmpC disk test. Seventeen isolates were identified as AmpC producer using combined disk method. Fifty two isolates showed a twofold or threefold dilution difference between the minimum inhibitory concentration of imipenem or ceftazidime and the minimum inhibitory concentration of imipenem or ceftazidime plus cloxacillin. One isolate was identified as AmpC producer using three methods. Three isolates produced AmpC as detected by both AmpC disk test and combined disk methods and 19 isolates were found as AmpC producer using both AmpC disk test and minimum inhibitory concentration methods. Six isolates were AmpC producer as shown by the MICs of both imipenem and ceftazidime.

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, AmpC- β-lactamase looks to be the main mechanism of resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to cephalosporins and carbapenems in the study hospital.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, β-lactam resistance, AmpC-β-lactamases

INTRODUCTION

β-lactamases enzyme are one of the major mechanism of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in many Gram negative bacilli such as Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomona aeruginosa (1,2). AmpC-β-lactamases are the main causes of resistance to β-lactams antibiotics such as extended spectrum cephalosporins, cephamycins, monobactams and carbapenems. Two features differentiate AmpC-β-lactamases from other β-lactamases such as Extended-Spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs): their resistance to ESBLs inhibitors such as clavulanate and their ability to hydolyze cephamycins such as cefoxitin and cefotetan (4,5). P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium that is responsible for severe nosocomial infections among patients with severe burns (3). AmpC in P. aeroginosa usually are encoded by the chromosomal genes and expressed constitutively at a low level (4). Mutations in ampC may lead to overproduction of AmpC-β-lactamases by some P. aeroginosa isolates (4). AmpC overproduction not only causes resistance to cephalosporins, cephamycin and monobactams but also is responsible for resistance to carbapenems (1,4). P. aeruginosa has emerged as important pathogen in Iran as in other countries, which presents serious challenges for hospital infection control practitioners and clinicians treating infected patients (6,7). There are several reports on the prevalence of MBLs and ESBLs among P. aeruginosa isolates in Iran, but the prevalence of AmpC overproduction isolates is unknown (8-10). The aim of this study was to detect the AmpC-β-lactamases producer isolates among carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolated from burn patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

We collected 100 nonconsecutive and non-duplicate of carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolates from different burn patients admitted at Shahid Motahari Burn Hospital in Tehran during 2011 and 2012. The isolates were identified by their cultural characteristics and reactions to standard biochemical tests.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The β-lactam antibiotic resistance pattern of isolates was determined by using disk diffusion method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines (11). The antibiotics were meropenem (MEM) (10μg), imipenem (IMI) (10μg), ertapenem (ETP) (10μg), cefotaxime (CTX) (30μg), ceftazidime (CAZ) (30μg), cefepime (CPM) (30μg) and cefoxitin (FOX) (30μg). All antibiotic disks were prepared form MAST Corporation (UK). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeroginosa ATCC 27853 and Klebsiella pneumoniae 700603 were used as a quality control strain for antimicrobial susceptibility test.

Detection of AmpC phenotype by phenylboronic acid

Detection of AmpC producer isolates by phenylboronic was performed as described by Song et al. (12). Briefly, disks cefoxitin (FOX, 30μg), cefotaxime (CTX, 30μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30μg) and cefepime (CPM, 30μg) alone and in combination with 400 μg phenylboronic acid (BA) were placed on the inoculated surface of the Mueller Hinton agar plate. Then the plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in ambient air. An increase of ≥5 mm in zone diameter of FOX, CAZ, CTX and CPM tested in combination with BA versus FOX, CAZ, CTX and CPM were considered as AmpC positive.

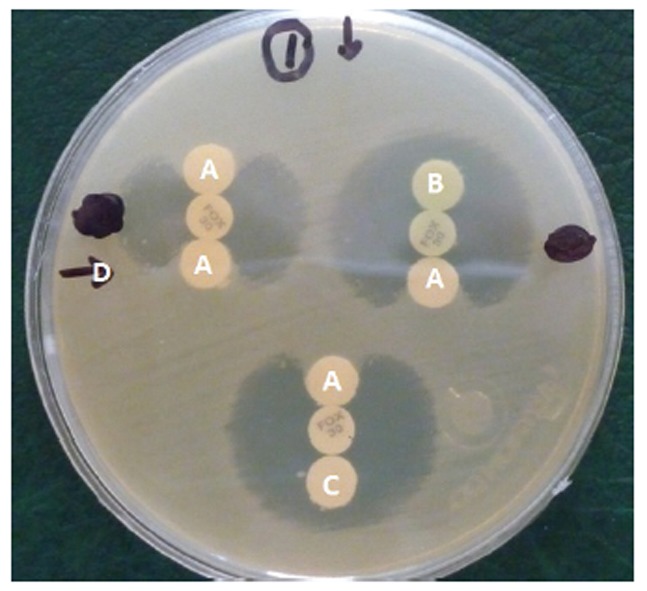

Detection of AmpC phenotype with the AmpC disk test

The AmpC disk test was performed as described by Black et al. (13). In brief, the surface of a Mueller-Hinton agar plate was inoculated with a lawn of the cefoxitin (FOX) susceptible (E. coli ATCC 25922) according to the standard disk diffusion method. A FOX (30μg) disk was placed on the bacterial lawn on the surface of the Mueller-Hinton agar and flanked by two blank disks, each containing 20 μl of a 1:1 mixture of saline and 100X Tris-EDTA solution. Colonies of the test strain and control strains were applied to blank disks (Fig.1). Flattening or indentation of the growth inhibition zone of the FOX disk at the side of blank disks containing the test strain indicated the release of AmpC-β-lactamase.

Fig. 1.

AmpC Disk Test.

A; Positive test,

B; Negative test,

C; Negative control (P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853),

D, Lawn culture (E. coli ATCC 25922).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis were carried out using SPSS 15 statistical software.

Detection of AmpC overproduction

AmpC overproduction confirmed according was to the method described by Rodriguez-Martinez et al. (7). The isolates were considering as AmpC overproducer when there was at least a twofold dilution difference between the MICs of imipenem (IMI) or ceftazidime (CAZ) and the MICs of IMI or CAZ plus cloxacillin (COL).

RESULTS

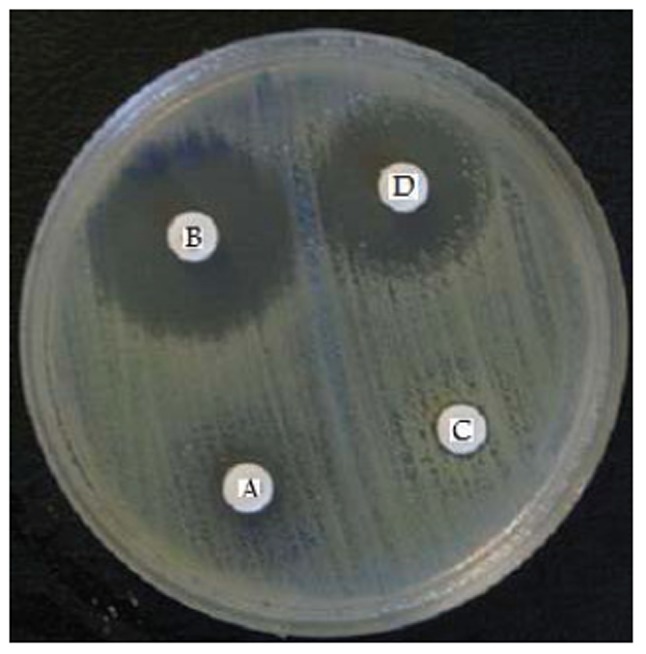

During the study, a total of 100 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa resistance to carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem or ertapenem) were collected from different burn patients who were admitted at Shahid Motahari Hospital of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Susceptibility results and MICs are shown in Table 1. Seventy carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa with MICs ≥32μg/ml for IMI were isolated from different patients. The MICs of CAZ against 70 isolates were ≥ 1024 μg/ml. Fifty two isolates showed a twofold or threefold dilution difference between the MICs of IMI or CAZ and the MICs of IMI or CAZ plus COL. MICs to imipenem and ceftazidime in AmpC overproduction isolates of P. aeruginosa with/without cloxacillin are shown in Table 2. The prevalence of AmpC-β-lactamases producers by three phenotypic methods is shown in Table 3. Fifty four isolates were recognized as AmpC producers in AmpC disk test (Fig. 1). Seventeen isolates showed AmpC-β-lactamases activity in combined disk method (Fig. 2). One isolate was identified as AmpC-β-lactamases producer using three methods. Three isolates were AmpC producer as shown by both AmpC disk test and combined disk methods and 19 isolates demostrated AmpC activity by both AmpC disk test and MIC methods. Six isolates were proved to be AmpC producer as determined by MICs of IMI and CAZ.

Table 1.

Susceptibility of clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa.

| Antibacterial agents | Susceptible (n) | Intermediately susceptible (n) | Resistant (n) | MIC50(μg/ml) | MIC90(μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMI | 0 | 0 | 100 | 64 | 64 |

| CAZ | 16 | 0 | 84 | 4096≤ | 4096≤ |

| MEM | 5 | 8 | 87 | ND | ND |

| ETP | 0 | 0 | 100 | ND | ND |

| CPM | 2 | 0 | 98 | ND | ND |

| CTX | 0 | 0 | 100 | ND | ND |

| FOX | 0 | 0 | 100 | ND | ND |

MEM: Meropenem, IMP: Imipenem, ETP: Ertapenem, CTX: Cefotaxime, CAZ: Ceftazidime, CPM: Cefepime, FOX: Cefoxitin.

ND: No determined.

Table 2.

MICs to imipenem and ceftazidime for AmpC overproduction isolates of P. aeruginosa whit/whitout cloxacillin.

| No. of Isolates | MIC (μg/ml) | No. of Isolates | MIC (μg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMI | IMI/CLO | CAZ | CAZ/COL | ||

| 19 | 64 | 16 | 5 | 4096 | 1024 |

| 5 | 128 | 32 | 2 | 2048 | 512 |

| 10 | 32 | 8 | 1 | 2048 | 256 |

| 3 | 64 | 8 | 1 | 1024 | 256 |

| 3 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 256 | 64 |

| 5 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 128 | 32 |

| ------- | ------- | ------- | 1 | 64 | 16 |

| ------- | ------- | ------- | 1 | 16 | 4 |

CAZ: ceftazidime, CAZ-CLO: ceftazidime-cloxacillin, IMI: imipenem, IMI-CLO: imipenem-cloxacillin.

Table 3.

Prevalence of AmpC phenotype by different methods in carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolates

| CTX+BA | CAZ+BA | CPM+BA | AmpC CAZ/COL | AmpC IMI/COL | AmpCdisk test | No. of Isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | + | - | - | - | 1 |

| - | - | + | - | - | + | 1 |

| - | + | + | - | + | - | 1 |

| - | + | + | - | - | + | 1 |

| + | - | + | - | - | + | 1 |

| - | + | + | - | + | + | 1 |

| - | + | - | + | + | - | 1 |

| - | + | - | - | + | - | 1 |

| + | + | + | + | - | - | 1 |

| + | + | + | - | - | - | 1 |

| + | - | - | - | + | - | 2 |

| - | - | - | + | + | - | 2 |

| - | - | - | + | + | + | 3 |

| - | - | - | + | - | + | 3 |

| - | - | - | + | - | - | 4 |

| - | - | + | - | + | - | 5 |

| - | - | - | - | + | - | 12 |

| - | - | - | - | + | + | 16 |

| - | - | - | - | - | + | 28 |

BA: Phenylboronic acid, CTX: Cefotaxime, CAZ: Ceftazidime, CPM: Cefepime, IMI: Imipenem, COL: Cloxacillin

Fig. 2.

AmpC-β-lactamase producing isolate:

A;Cefepime,

B; Cefepime + Phenylboronic acid(BA),

C; Ceftazidime,

D; Ceftazidime + BA.

DISCUSSION

In this study, AmpC disk test method identified 54 isolates as AmpC producer and combined disk method identified 17 isolates as AmpC producer. This result shows a probable activation of one of the efflux pumps system and impermeability, or both, against β-lactam antibiotics which causes falsely negative results in AmpC-β-lactamase detections in combined disk method. Resistance to cefoxitin is suggestive of an AmpC enzyme, but it is not specific since cefoxitin resistance can also be produced by certain carbapenemases and a few class A β -lactamases and by decreased levels of production of outer membrane porins (1). AmpC-β-lactamase not only cause hydrolysis and resistance to broad spectrum cephalosporins, aztreonam and cephamycins, but also cause hydrolysis of carbapenems and increase resistance to these antibiotics. Carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa due to AmpC overproduction have been reported in many countries (7,14). Lee and Rodriguez et al., reported that AmpC-β-lactamase causes an increase of MIC to carbapenems, aztreonam and cephalosporins among 47% and 87% clinical P. aeruginosa isolates, respectively (7,14). They reported that 51% of carbapenem-resistant clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa in their study overproduced AmpC-β-lactamase (15). In the present study, MICs of IMI and CAZ among 52 isolates reduced after adding cloxacillin, suggesting that the main mechanism associated with susceptibility reduction or resistance to imipenem was probably overexpression of AmpC and could therefore play an additive role in susceptibility reduction or resistance to imipenem. However, literatures suggested that AmpC-β-lactamase alone does not responsible for carbapenem resistant but could certainly increase the minimum inhibitory concentrations to β-lactamas antibiotics such as carbapenems and usually coupled with other mechanism specially loss of OprD porin (4, 16). It seems that the mechanisms leading to carbapenem resistance in Iran are more complex and are very likely multifactorial, involving overproduction of AmpC or Metallo-β-Lactamases (8-10). The simultaneous presence of these mechanisms of resistance causes an overlap and concealing of their resistance rates and therefore the interpretation of the phenotype appointing the relevant methods would be difficult. It also causes the increase of MICs in comparison with beta-lactam antibiotics resulting in a defeat of the remedy of infections with β-lactam antibiotics (1,5).

In conclusion, results of this study, showed that AmpC-β-lactamases are responsible for decreasing the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to different classes of β-lactam antibiotics in this region of Iran. A phenotypic test alone can not detect AmpC-β-lactamase-producing isolates. It highlights the necessity of different phenotypic methods for identification of AmpC-β-lactamase producing isolates among P. aeruginosa strains.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences & Health Services, Grant 19204/30-4-91.

References

- 1.Jacoby GA. AmpC beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:161–82. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson KS. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase, AmpC, and Carbapenemase issues. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1019–25. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00219-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tredget EE, Shankowsky HA, Rennie R, Burrell RE, Logsetty S. Pseudomonas infections in the thermally injured patient. Burns. 2004;30:3–26. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;24:582–610. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundin S. Hidden Beta-Lactamases in the Enterobacteriaceae - dropping the extra disks for detection, Part II. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 2009;31:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jabalameli F, Mirsalehian A, Sotoudeh N, Jabalameli L, Aligholi M, Khoramian B, Taherikalani M, Emaneini M, et al. Multiple-locus variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) fingerprinting (MLVF) and antibacterial resistance profiles of extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa among burnt patients in Tehran. Burns. 2011;37:1202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Martinez M, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4783–87. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00574-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khosravi AD, Mihani F. Detection of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients in Ahwaz, Iran. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60:125–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahar MA, Jamali S, Samadikuchaksaraei A. Imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains carry metallo-beta-lactamase gene bla(VIM) in a level I Iranian burn hospital. Burns. 2010;36:826–30. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirsalehian A, Feizabadi M, Nakhjavani FA, Jabalameli F, Goli H, Kalantari N. Detection of VEB-1, OXA-10 and PER-1 genotypes in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients. Burns. 2010;36:70–4. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Twenty- First Inform Suppl, M100-S21. 2011;31 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song W, Hoon Jeong S, Kim JS, Kim HS, Shin DH, Roh KH, et al. Use of boronic acid disk methods to detect the combined expression of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-Lactamase and extended-sprctrum β-Lactamase in clinical isolates off Klebsiella Spp.,Salmonella Spp., and Proteus mirabilis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57:315–18. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black JA, Smith Moland E, Thomson KS. AmpC disk test for detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-Lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae lacking chromosomal AmpC β-Lactamases. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3110–3113. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3110-3113.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Ko KS. OprD mutations and inactivation, expression of efflux pumps and AmpC, and metallo-β-lactamases in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from South Korea. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez O, Juan C, Cercenado E, Navarro F, Bouza E, Coll P, et al. Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Spanish hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4329–4335. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00810-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poole K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2011;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]