Abstract

Background:

Oral mucosa is often affected by many diseases including mucocutaneous disorders. The diagnoses of these disorders are primarily based on history, clinical features, and histopathology. For the past few years’ immunofluorescence techniques emerged as an important tool to study the pathogenesis and in the diagnosis of oral mucocutaneous and vesiculobullous disorders. The present study was designed to carry out retrospective and prospective analysis of oral mucocutaneous lesions to elucidate the clinicopathologic features and its immunofluorescence findings.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 70 subjects with oral mucocutaneous lesions were retrieved from the oral pathology files of Tamil Nadu Govt. Dental College and their clinical features were evaluated, and the histopathology was also evaluated with the help of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. For the prospective study, biopsy from 12 subjects with oral mucocutaneous lesions was subjected to routine histopathological examination and DIF to evaluate the consistency of the methods.

Results:

In the retrospective analysis of 70 subjects with oral mucocutaneous lesions in relation to clinical features and histopathology, most of the findings were similar to the previous studies except for few criteria like male predilection in lichen planus and mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) and more prevalence of pemphigus vulgaris than MMP (2:1). In the prospective analysis of 12 subjects, the histopathological diagnosis was consistent with DIF study in 66% of cases.

Conclusion:

The diagnostic efficiency of oral mucocutaneous lesions can be improved by modern tools like DIF studies in addition to traditional methods like clinical and histopathology.

Keywords: Histopathology, immunofluorescence, mucocutaneous lesions, oral

Introduction

Oral mucosa is often affected by many diseases including mucocutaneous disorders. The diagnoses of these disorders are primarily based on history, clinical features, and histopathology. The oral mucocutaneous lesions cause diagnostic problems, as these lesions resemble each other, and routine tissue biopsies may only offer a diagnosis of non-specific inflammation.1

For the past few years, immunofluorescence techniques emerged as an important tool in detecting the pathogenesis and diagnosis of oral mucocutaneous lesions (and vesiculobullous disorders). Two types of immunofluorescence techniques that commonly followed are direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF).

In some diseases, IIF studies have revealed circulating autoantibodies2,3 whereas DIF studies have revealed immunoglobulins, complement components and other protein substances within the affected tissue.4 These circulating and tissue-bound substances may have a role in the immunopathogenesis of these diseases. In addition detection of these immune reactive substances by DIF aids in the diagnosis of many skin and mucosal diseases.1 The presence of characteristic fluorescent patterns in DIF can definitely establish the diagnosis of pemphigus and pemphigoid and strongly indicate the likelihood of lichen planus (LP) and lupus erythematosus. The absence of these fluorescent patterns rules out these conditions, thereby strengthening the diagnosis of other oral mucosal diseases. The results of DIF are sufficiently useful in the diagnosis of chronic ulcerative diseases of the oral mucosa.1

Based on these facts, a prospective study of oral mucocutaneous lesions was designed to evaluate the consistency of the histopathology with DIF. A retrospective analysis of the prevalence of oral mucocutaneous lesions namely oral LP (OLP), discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), and mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) were also studied with regards to demographic details and histopathological features (hematoxylin and eosin stained sections) that are characteristic of each disease were evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Twenty consecutive subjects in each of OLP, DLE, PV, and ten consecutive subject of MMP (total 70 subjects) were retrieved from the oral pathology files of Tamil Nadu Govt. Dental College and reviewed for salient features including age, gender, and intraoral site of the lesion. Hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stained sections of all the 70 subjects were reviewed, and the histopathological patterns were evaluated (retrospective study).

Twelve subjects with chronic or recurrent ulcerative or erosive or vesiculobullous diseases of the oral mucosa were included for the prospective study. Biopsy specimens were taken from the perilesional area in all the 12 subjects. Specimens were examined by routine histopathological methods (H and E) and DIF. Specimens for DIF study were quickly washed in normal saline and stored immediately in Michel’s media and transported to the laboratory.

Results

Retrospective evaluation

The retrospective study comprised of 70 subjects - 20 subjects in each of OLP, DLE, and PV and 10 subjects of MMP. The following significant results were derived (Table 1).

Table 1.

Retrospective analysis showing the demographic and histopathological details.

OLP

Eleven males affected against 9 females (1:0:81). Fifth decade was predominantly involved - 30% (6 subjects). Youngest involved was 11 years, and oldest was 72 years, mean age - 42.05 years. Buccal mucosa was involved in 85% of the subject. Histopathologically, basal cell degeneration and subepithelial band of chronic inflammatory cells were seen in 100% of subjects.

PV

Seven males affected against 13 females, sixth decade was predominantly involved - 45% (9 subjects). Youngest individual was 33 years, and oldest was 78 years mean age - 52 years. Buccal mucosa was involved in 60% of subjects. Histopathologically, epithelium ulcerated in 40% of subjects, intact basal cells attached to connective tissue seen in 100% of subjects, acantholytic (Tzanck) cells seen in 85% of subjects and dense chronic inflammatory cells seen in the connective tissue in 55% subjects.

MMP

Seven males affected against 3 females (1:0.42) fifth and sixth decades were predominantly involved - 60% (6 subjects). Youngest individual was 33 years, and oldest was 70 years, mean age - 48 years. Gingiva was involved in 60% of subjects. Nikolsky’s sign positive in 40% of subjects. Histopathologically, subepithelial split was seen in 100% of the subjects, 40% showed inflammatory cells and red blood cells in the split, diffuse chronic inflammatory cells seen in the connective tissue in 90% of subjects and increased vascularity seen in 50% of subjects.

DLE

Five males affected against 15 females (1:3), third and fourth decades were predominantly involved - 45% (9 subjects). Youngest individual was 17 years, and oldest was 70 years mean age - 42 years. Lip was involved in 85% of subjects. Histopathologically, basal cell degeneration was seen in 80% and perivascular chronic inflammatory cells in 85% of subjects.

Prospective evaluation

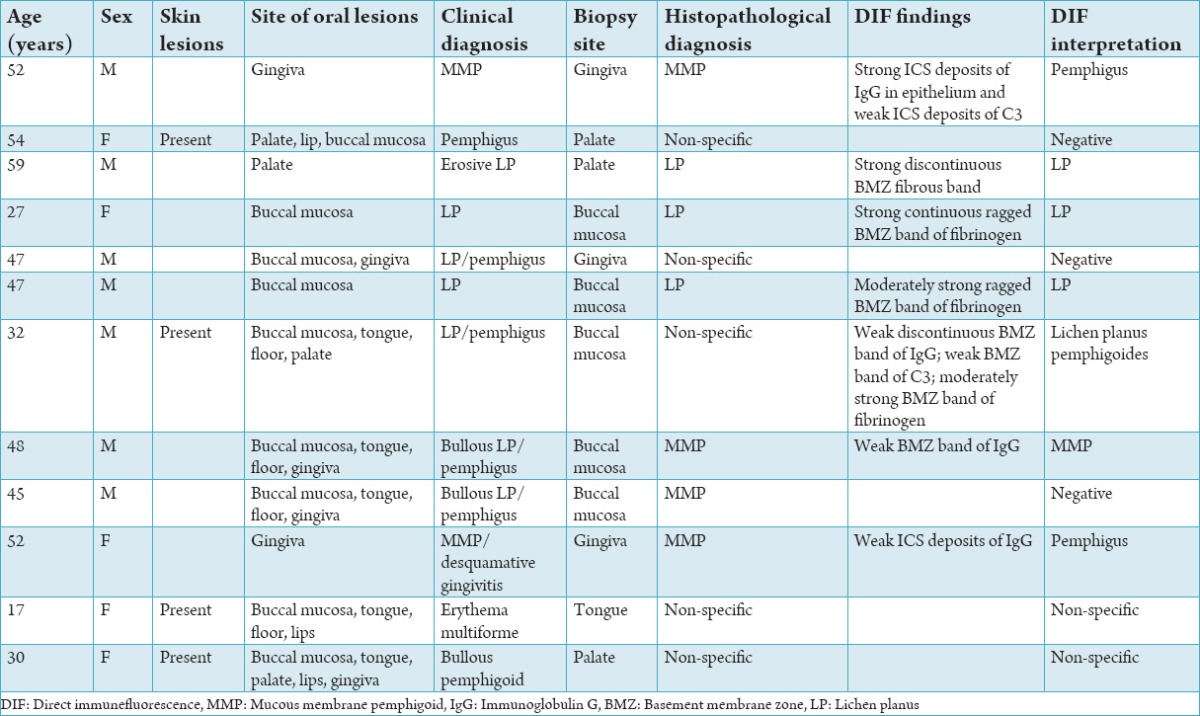

12 cases of oral mucocutaneous lesions were subjected to routine histopathological and DIF analysis. Histopathology showed 3 cases of LP, 4 cases of MMP and 5 cases were diagnosed as non-specific chronic inflammatory lesions. In DIF study - 5 subjects were negative. 3 were reported as OLP (Figure 1), 2 were interpreted as PV (Figure 2) and 1 each of MMP (Figure 3) and LP pemphigoides (Figure 4). Histopathological diagnosis consistent with DIF in 8 cases (66%) (3 OLP, 1 MMP and 4 non-specific inflammation).

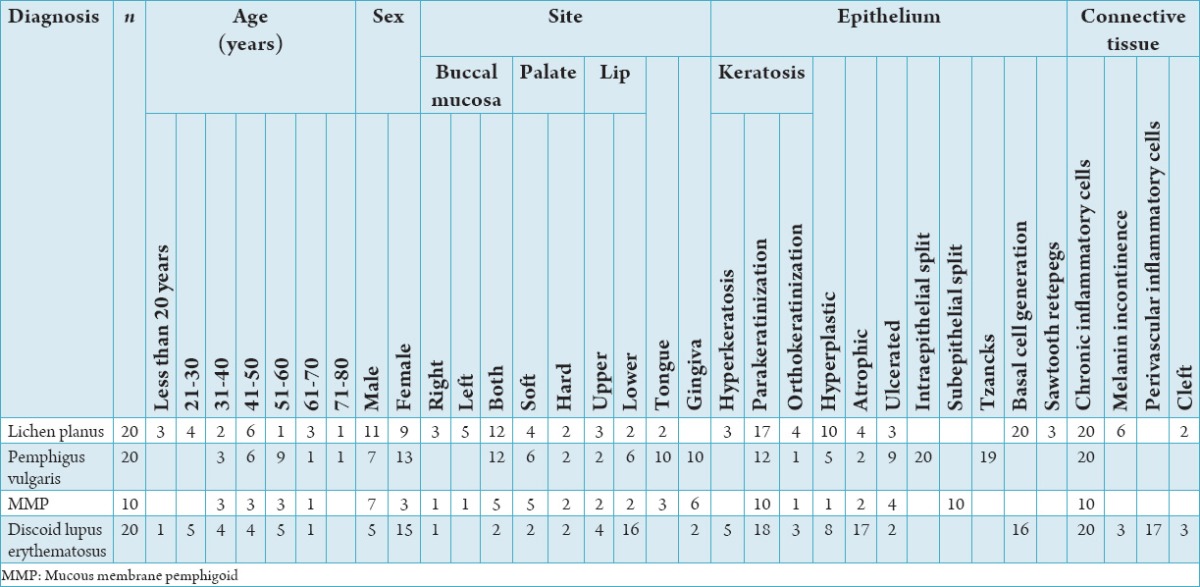

Figure 1.

(Lichen planus), (a) Hyperkeratosis, basal cell degeneration of epithelium along with subepithelial band of chronic inflammatory cells (H and E, ×10), (b) direct immunofluorescence showing fibrin deposition along the basement membrane zone.

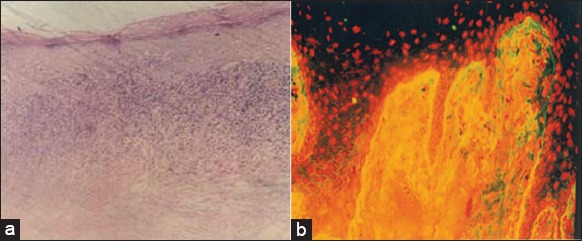

Figure 2.

(Pemphigus vulgaris) (a) Supra basal cleft with Tzanck cells and intact basal layer (H and E, ×40), (b) direct immunofluorescence showing intercellular space deposition of immunoglobulin G in the epithelium.

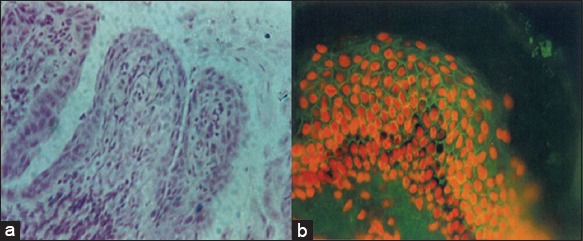

Figure 3.

(Mucous membrane pemphigoid) (a) Subepithelial cleft between epithelium and connective tissue (H and E, ×10), (b) direct immunofluorescence showing smooth, linear, and continuous band of C3 deposit along the basement membrane zone.

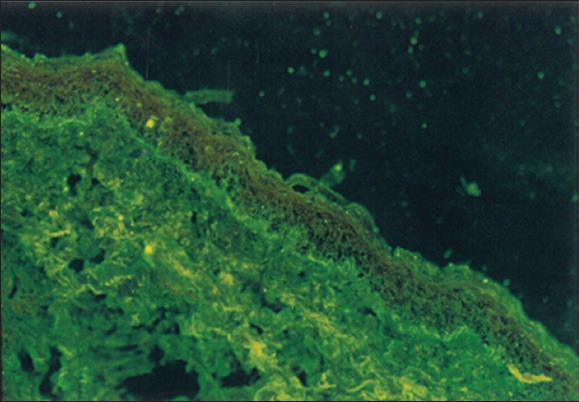

Figure 4.

(Lichen planus pemphigoides) direct immunofluorescence showing linear deposit of C3 along the basement membrane zone.

The histopathological diagnosis and DIF study were not consistent in four subjects in which one case diagnosed histopathologically as non-specific chronic inflammatory lesion showed positivity for LP pemphigoides in DIF. Among the other three cases, one diagnosed histopathologically as MMP was negative in DIF and two cases which were diagnosed as MMP histopathologically were found to show positivity for PV in DIF (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prospective analysis showing the histopathological correlation with the immunofluorescence findings.

Discussion

Mucocutaneous disorders (LP, DLE, PV, and MMP) usually present themselves as chronic recurring ulcerations or vesiculobullous lesions, causing patients to seek diagnosis and treatment. Though histopathology remains the gold standard for the diagnosis, in the past few year immunofluorescent techniques emerged as a valuable tool in the diagnosis of ulcerative and vesiculobullous – mucocutaneous disorders.1

LP is predominantly a disease of the middle-aged and elderly with age ranging between 30 and 70 years.5 In the present study also, 65% of the patients were in the same age groups. LP affects both the sexes, although occasionally some survey have suggested a male predominance, majority suggested a female predilection.6,7

The slight male predilection in the present study (M: F=1:0.81) may be due to the small sample size. Similar to the most of the studies in the literature,5 the present study also showed buccal mucosal predominance. Similar to most of the studies,6 histopathology of the present study also showed hyperorthokeratosis, basal all degeneration, and subepithelial band of chronic inflammatory cells in 60%, 100%, and 100% of the subjects, respectively.

DLE is a disease commonly seen in the third and fourth decades. It is also considerably more common in women than men.6,8 The present study also showed most of the subjects in the third and fourth decades (45%) with a male:female ratio of 1:3.

As with the other studies,8,9 lip is the most common site of involvement in the present study (85%). A survey of literature showed that DLE lesions are characterized by hyperkeratosis, basal cell degeneration, perivasular lymphocytic infiltrate, and band like inflammatory cells in the lamina propria.10

The present study also showed basal cell degeneration, subepithelial band of chronic inflammatory cells, and perivascular chronic inflammation in 80%, 55%, and 85%, of the subjects, respectively. Epithelial atrophy alternating with hyperplasia showed a high diagnostic value for DLE against LP.10 This feature was seen in 35% subjects of the present study.

PV predominantly seen between third and seventh decades and females were commonly involved. In the present study also 96% of the subjects were between third and seventh decades and female to male ratio was 1:0.53. As with the majority of the studies6,8,11 in the present study also buccal mucosa was affected in 60% of the subjects. The formation of bulla is entirely intraepithelial just above the basal layer,8 Tzanck cells and intact basal cells attached to connective tissue were seen in 80%, 85%, and 100% of the subjects, respectively. These findings were in accordance with other studies. In contrast to other studies,8,11 present study showed dense chronic inflammatory cells infiltrate in 55% of subjects.

MMP usually affects older persons (fifth-eighth decade), females are commonly involved (F:M: 2:1)6 In the present study also 70% of the patients were in the age group of fifth to eighth decades. More number of males (70%) affected in the present study may be attributed to the small sample size. Gingiva is the most common site of involvement followed by buccal mucosa.8,12

In the present study also gingiva was involved in 60% of subjects and buccal mucosa was also equally involved. The sub epithelial split and diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate were seen in 100% and 90% of the subjects, this is in accordance with the previous studies.8,12

In our prospective study of 12 subjects of oral mucosal lesions by DIF, 5 were negative, 3 were LP, 2 were PV, and one each of MMP and LP pemphigoides. Histopathological diagnosis was consistent with DIF in 66% of subjects, and this was in accordance with the previous studies by Daniels and Carmen.1 Histopathological and DIF results were similar in 3 cases of OLP, and one case of MMP and 4 subjects which were found to be non-specific inflammation were also found to be negative in DIF study.

Negative results in DIF will help us to rule out those diseases which produces specific fluorescent patterns and thereby strengthening the diagnosis of other oral mucosal lesions.

Though in some cases histopathology is not consistent with DIF both were able to offer diagnosis in 2/3 of the subjects. Early diagnosis of MMP is important since the prevalence of concurrent eye lesions is greater with oral lesions. DIF is more specific and sensitive than histopathology and electron microscopy in diagnosing MMP.13-15 Immunofluorescence analysis is also a helpful tool in monitoring therapeutic responses of these lesions by analyzing the lesion specific autoantibodies.16

Conclusion

Although the histopathology remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of most of the diseases, it is inferred from this study that not all lesions are amenable to a definitive diagnosis. Due to the accuracy of DLF study in diagnosing diseases, its report is taken as the final diagnosis, which ascertains the course and prognosis of the disease. However, the consistency of the DLF in this study cannot be substantiated due to the limited sample size which is attributed to cost effectiveness of the DLF technique.

Acknowledgments

The primary author would like to acknowledge the valuable inputs by KA Annasamy and A Vathsala and also would like to thank A Panneerselvam, A Alaguselvam, P Kunthavai, A Girija, Dr. S Shanthy, P Chandrabanu and P Sathya in preparing the manuscript and proofreading.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Source of Support: Nil

References

- 1.Daniels TE, Quadra-White C. Direct immunofluorescence in oral mucosal disease: A diagnostic analysis of 130 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;51(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutner EH, Chrozelski TP, Kumar V Immunopathology of Skin. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6):803–22. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dayan S, Simmons RK, Ahmed AR. Contemporary issues in the diagnosis of oral pemphigoid: A selective review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88(4):424–30. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallaoglu N. Oral lichenplanus - A review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38(4):370–7. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen C, Neville B, Damm D, Bouquot J Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 1st ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scully C, el-Kom M. Lichen planus: Review and update on pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14(6):431–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM Text Book of Oral Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ Oral Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiødt M. Oral discoid lupus erythematosus. III. A histopathologic study of sixty-six patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:281–93. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinberg MA, Insler MS, Campen RB. Mucocutaneous features of autoimmune blistering diseases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84(5):517–34. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming TE, Korman NJ. Cicatricial pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(4):571–91. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.107248. quiz 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eschle-Meniconi ME, Ahmad SR, Foster CS. Mucous membrane pemphigoid: An update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2005;16(5):303–7. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000179802.04101.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel E, Thorne JE. Recent advances in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19(4):292–7. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328302cc61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan LS. Ocular and oral mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid) Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(1):34–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knudson RM, Kalaaji AN, Bruce AJ. The management of mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(3):268–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]