Abstract

Background

Whether right ventricular (RV) dysfunction affects clinical outcome after CABG with or without SVR is still unknown. Thus, the aim of the study was to assess the impact of RV dysfunction on clinical outcome in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with or without surgical ventricular reconstruction (SVR).

Methods and Results

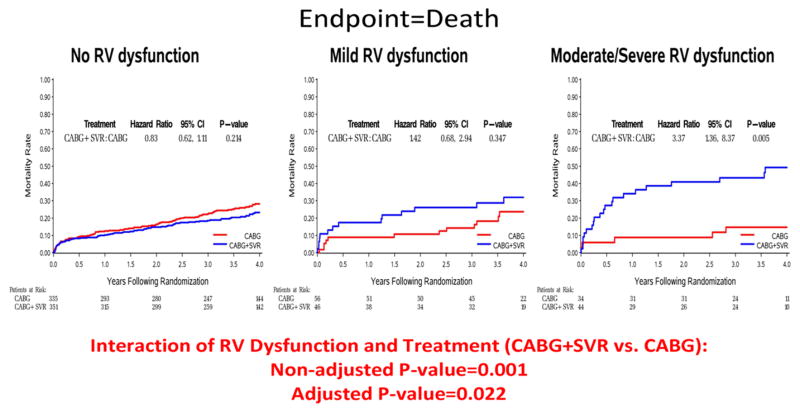

Of 1,000 STICH patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) ≤35% and anterior dysfunction randomized to undergo CABG or CABG + SVR, baseline RV function could be assessed by echocardiography in 866 patients. Patients were followed for a median of 48 months. All-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization was the primary endpoint, and all-cause mortality alone was a secondary endpoint. RV dysfunction was mild in 102 (12%) patients and moderate or severe in 78 (9%) patients. Moderate to severe RV dysfunction was associated with larger LV, lower EF, more severe mitral regurgitation, higher filling pressure, and higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure (all p<0.0001) compared to normal or mildly reduced RV function. A significant interaction between RV dysfunction and treatment allocation was observed. Patients with moderate or severe RV dysfunction who received CABG + SVR had significantly worse outcomes compared to patients who received CABG alone on both the primary (HR=1.86; CI=1.06–3.26; p=0.028) and the secondary endpoint (HR=3.37; CI=1.36–8.37; p=0.005). After adjusting for all other prognostic clinical factors, the interaction remained significant with respect to all-cause mortality (p=0.022).

Conclusion

Adding SVR to CABG may worsen long-term survival in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with moderate to severe RV dysfunction, which reflects advanced LV remodeling.

Keywords: Right ventricular function, echocardiography, SVR, CABG, ischemic cardiomyopathy

Introduction

In patients with heart failure (HF), right ventricular (RV) systolic dysfunction has been associated with decreased exercise capacity (1, 2) and a poor clinical outcome (3–7) when compared to patients who have preserved RV function. However, the small numbers of patients described in previous studies of RV dysfunction severely limit an assessment of the prevalence of RV dysfunction in patients with HF. Moreover, the clinical implications of RV dysfunction in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who undergo coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) with or without surgical ventricular reconstruction (SVR) have not been clearly defined. The Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) trial (8) provides a unique opportunity to assess the importance of RV dysfunction in the above clinical situation. In the STICH trial, the Echocardiography Core Laboratory (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) provided a baseline echocardiographic evaluation of structural, functional, and hemodynamic parameters of both LV and RV. The STICH trial tested two clinically unresolved and relevant hypotheses in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and reduced LV ejection fraction (EF). The SVR hypothesis (Hypothesis 2) of STICH randomized 1,000 patients with anteroapical dysfunction to CABG with SVR versus CABG alone, to test the hypothesis that in patients with LVEF ≤ 35%, CAD amenable to CABG and anterior LV dysfunction, adding SVR improves survival free of subsequent hospitalization for cardiac cause in comparison to CABG alone (8). The concept and technique of surgical ventricular restoration has been well described by Dor et al (9). The primary outcome of this population has been already reported by Jones et al (10) and the description of clinical characteristics by Zembala et al (11). Hypothesis 2 patients were followed for a median of 48 months. Only 4 of the 1000 patients withdrew consent for follow up and 6 patients were lost to follow up.

The present study sought to examine the prevalence of RV dysfunction in those 1,000 patients to determine the relationship between RV dysfunction and other parameters of cardiac structure and function measured by echocardiography. We also examined the interaction of RV dysfunction with treatment on short-term and long-term survival in these patients.

Methods

Study Population and Patient Selection

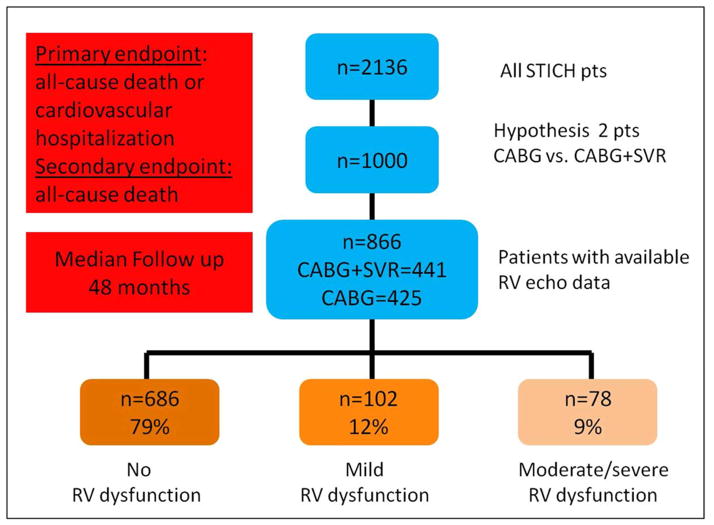

Among the 2,136 patients enrolled into the STICH trial with an LVEF ≤ 35% and CAD amenable to CABG, 1,000 patients with anteroapical dysfunction for which adding an SVR operation to CABG was reasonable but not required were randomized to CABG vs. CABG +SVR. Of the 1000 patients enrolled, 866 patients had a baseline echocardiogram rated as fair to excellent quality (excellent for textbook quality, good for clear definition of RV walls from multiple views, and fair for good definition of RV walls from limited views) for qualitative assessment of RV function by the Echocardiography Core Laboratory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chart Illustrating the Design of STICH Patient Selection for RV Function Analysis

SVR-surgical ventricular reconstruction, CABG-Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

Echocardiography Study

Baseline echocardiography was obtained within 3 months prior to enrollment by clinical sites and sent to the Echocardiography Core Laboratory where each study was initially analyzed by a research sonographer blinded to randomized treatment assignment and clinical outcomes using American Society of Echocardiography guidelines (12) and with a second over-read by a physician. Details of the methodology used for echocardiographic analysis have been previously published (13).

RV Function Assessment

RV function was assessed prospectively by visual interpretation and categorized as normal, mild, moderate or severe dysfunction. The appreciation of the overall mechanical function of the RV was mainly based on the extent of RV free wall segmental motion, wall thickening, RV cavity size, and subjective assessment of RV area change (normal >50%, mild 30–50%, moderate 20–30%, and severe <20 % from diastole to systole) RV assessment was derived from the parasternal long axis, apical 4-chamber, and subcostal views. This assessment was based on visual assessment by an experienced Echocardiography Core Laboratory physician (14).

Once the results of the impact of RV function by visual assessment was known, 40 patients in each group, normal, mild and moderate dysfunction, and all 21 patients with severe RV dysfunction were sent for blinded post-hoc calculation of RV fractional area change. RV fractional area change was calculated from apical four chamber views as [(RV end diastolic area – RV end systolic area)/ RV end diastolic area] by a research sonographer without any knowledge of patient’s clinical or other echocardiography data.

Statistics

Clinical and echocardiographice characteristics were described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Due to the limited number of patients with moderate and severe RV dysfunction these two groups have been combined and analyzed as one moderate/severe subgroup. Comparisons of patients across 3 different levels of RV dysfunction (i.e., normal, mild, or moderate/severe) were performed using Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis of variance on continuous and ordinal variables. Group comparisons of nominal categorical variables were performed using the conventional chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test. The prognostic effect of RV dysfunction on the short-term endpoint of death within 30 days after surgery was tested using the logistic regression model. The effects of the 3 levels of RV dysfunction on the long-term endpoints of (a) death or cardiovascular hospitalization, and (b) all-cause mortality as well as relative risks were assessed using the Cox regression model. Event-rate estimates in each RV dysfunction group for each long-term endpoint were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The logistic regression model and Cox regression model were also used to assess the interaction of RV dysfunction and treatment (CABG vs. CABG + SVR). Testing of the independent prognostic effect of RV dysfunction and that of the interactive effect of RV dysfunction and treatment were performed after adjusting for LVEF and other key prognostic factors identified from previous modeling analyses of the STICH SVR hypothesis patient data.

Results

Patients

The study patients (n=866) consisted of 739 men (85%) and 127 women (15%) with a mean age of 62 ± 10 years randomized to CABG alone (n=425) and to CABG + SVR (n=441) (Figure 1). At baseline, patients with moderate to severe RV dysfunction had more advanced HF, a higher percentage with atrial fibrillation, a lower percentage with prior myocardial infarction, higher levels of creatinine and BUN, required more diuretic therapy, and walked shorter distances in the 6-minute walk test (Table1).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of the Analyzed Cohort of Patients (N=866) Categorized by RV Dysfunction Status

| Clinical and Laboratory Variables | Total Cohort N=866 |

No RV Dysfunction N=686 |

Mild RV Dysfunction N=102 |

Moderate/ Severe RV Dysfunction N=78 |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | 61.6±9.8 | 61.9±9.7 | 60.2±10.2 | 60.7±10.6 | 0.246 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 27.4±4.4 | 27.6±4.3 | 27.2±4.9 | 26.6±5.2 | 0.159 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 289 (33.4) | 218 (31.8) | 41 (40.2) | 30 (38.5) | 0.148 |

| Chronic renal insufficency n (%) | 73 (8.4) | 53 (7.7) | 10 (9.8) | 10 (12.8) | 0.270 |

| Hypertension n (%) | 502 (58.0) | 402 (58.6) | 59 (57.8) | 41 (52.6) | 0.592 |

| Atrial fibrillation n (%) | 98 (11.3) | 65 (9.5) | 17 (16.7) | 16 (20.5) | 0.003 |

| Prior MI n (%) | 754 (87.1) | 611 (89.1) | 87 (85.3) | 56 (71.8) | ≤0.001 |

| Diuretics (loop/thiazide) n (%) | 511 (59.0) | 382 (55.7) | 65 (63.7) | 64 (82.1) | ≤0.001 |

| Diuretics (K+ sparing) n (%) | 325 (37.5) | 236 (34.4) | 48 (47.1) | 41 (52.6) | 0.001 |

| Statin n (%) | 668 (77.1) | 544 (79.3) | 73 (71.6) | 51 (65.4) | 0.008 |

| Beta blocker n (%) | 745 (86.0) | 603 (87.9) | 77 (75.5) | 65 (83.3) | 0.003 |

| Aspirin n (%) | 663 (76.6) | 540 (78.7) | 68 (66.7) | 55 (70.5) | 0.012 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1±0.4 | 1.1±0.3 | 1.2±0.7 | 1.3±0.5 | 0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 28.6±20.1 | 26.7±16.5 | 31.6±27.0 | 38.8±29.7 | 0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 120.7±17.7 | 121.7±17.7 | 117.9±17.0 | 115.1±16.8 | 0.001 |

| NYHA class III n (%) | 373 (43.1) | 282 (41.1) | 51 (50.0) | 40 (51.3) | ≤0.001 |

| NYHA class IV n (%) | 46 (5.3) | 26 (3.8) | 4 (3.9) | 16 (20.5) | ≤0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72.5±13.3 | 71.6±12.9 | 75.8±16.2 | 75.8±11.7 | ≤0.001 |

| 6-min walk distance (m) | 347.2±120.5 | 351.8±116.5 | 355.8±124.9 | 285.4±137.2 | 0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BUN, blood-urine-nitrogen; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RV, right ventricular

P-differences between RV dysfunction groups

Prevalence of RV Dysfunction and Its Association

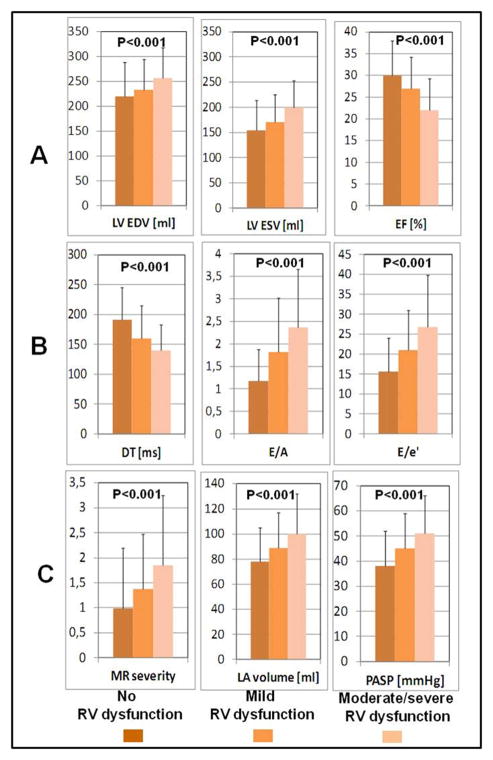

RV function was normal in 686 patients (79%), mildly reduced in 102 patients (12%), and moderately to severely reduced in 78 patients (9%) (Figure 1). Of the patients sent for post-hoc analyses of RV fractional area change, measurements could only reliably be performed in 20 normal patients, 25 wth mild RV dysfunction, 22 with moderate RV dysfunction, and16 with severe dysfunction. RV fractional area change was 50.1± 9.1, 34.6± 5.5, 27.5± 4.9, and 17.6± 3.7 %, respectively (p < 0.001). Two-dimensional, Doppler, and tissue Doppler echocardiography data in the 3 groups of patients defined by RV function as 1) normal; 2) mild; and 3) moderate to severe dysfunction are shown in Table 2. Both LV end diastolic and LV end systolic volumes increased progressively with increasing RV dysfunction (Table 2, Figure 2). In parallel, LVEF was progressively reduced with worsening of RV dysfunction. All LV diastolic function and filling parameters (E/A ratio, deceleration time, E/e, and LA volume index) were progressively worse with more severe RV dysfunction indicating higher LV filling pressure with worsening RV dysfunction. Mitral regurgitation was more severe and Doppler derived pulmonary artery systolic pressure was higher in patients with moderate to severe RV dysfunction compared to the patients with normal RV function or mild dysfunction (Table 2, Figure 3).

Table 2.

Baseline Echocardiographic Characteristics of the Analyzed Cohort of Patients (N=866) Categorized by RV Dysfunction Status

| Echo Variables | Total Cohort N=866 |

No RV Dysfunction N=686 |

Mild RV Dysfunction N=102 |

Moderate/ Severe RV Dysfunction N=78 |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDV (ml) | 225±69 | 220±68 | 234±69 | 256±68 | <0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 161±60 | 155±58 | 172±60 | 199±61 | <0.001 |

| LVED Index (ml/BSA) | 117±35 | 114±34 | 123±32 | 137±40 | <0.0001 |

| LVES Index (ml/BSA) | 84±31 | 80±30 | 90±29 | 107±35 | <0.0001 |

| EF (%) | 29±8 | 30±7 | 27±7 | 22±6 | <0.0001 |

| Sphericity Index | 1.49±0.19 | 1.50±0.19 | 1.47±0.18 | 1.45±0.16 | 0.063 |

| Global hypokinesis n (%) | 84 (9.7) | 62 (9.1) | 12 (11.8) | 10 (12.8) | 0.433 |

| Wall Motion Score Index | 2.22±0.33 | 2.18±0.33 | 2.32±0.30 | 2.44±0.24 | <0.001 |

| Inferior Basal WMSI | 2.08±0.80 | 2.02±0.81 | 2.21±0.75 | 2.43±0.70 | <0.001 |

| Apical WMSI | 2.87±0.45 | 2.88±0.46 | 2.85±0.34 | 2.90±0.42 | 0.489 |

| E DT (ms) | 184±54 | 192±53 | 161±45 | 140±40 | <0.001 |

| E/A | 1.33±0.91 | 1.17±0.75 | 1.82±1.08 | 2.36±1.28 | <0.001 |

| E/E′sep | 17±9 | 16±8 | 21±10 | 27±17 | <0.001 |

| E/E′lat | 14±10 | 13±8 | 16±11 | 20±21 | 0.059 |

| Diastolic filling pattern | 2.91±0.77 | 2.80±0.74 | 3.4±0.78 | 3.46±0.79 | <0.001 |

| MR Severity | 1.11±0.95 | 0.99±0.85 | 1.38±1.03 | 1.85±1.22 | <0.001 |

| LA volume (ml) | 82±29 | 78±27 | 89±30 | 101±30 | <0.001 |

| TRvelocity (m/s) | 2.83±0.55 | 2.73±0.50 | 2.97±0.57 | 3.12±0.63 | <0.001 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 42±15 | 39±14 | 45±14 | 52±16 | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume (ml) | 66±19 | 68±18 | 61±20 | 53±17 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac Output (ml) | 4519±1384 | 4634±1399 | 4236±1227 | 3699±1115 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac Index (ml) | 2334±708 | 2382±722 | 2253±602 | 1924±563 | ≤0.001 |

LVEDV-left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESV-left ventricular end systolic volume; MR-mitral regurgitation, WMSI-wall motion score index; TR-tricuspid regurgitation; PASP-pulmonary artery systolic pressure; EF-ejection fraction; BSA-body surface area; E-early diastolic velocity; E/A-early/late velocity ratio; LA-left atrium; E/E′-early mitral/annular velocity ratio; E/E′lat ratio; LVED-left ventricular end-diastolic ; LVES-left ventricular end-systolic; DT-deceleration time; RV-right ventricular

P-differences between RV dysfunction groups

Figure 2.

Associations between Degree of RV Dysfunction

A – LV remodeling expressed by LV EDV, LV ESV and LVEF; B – LV diastolic properties represented by DT, E/A, E/e′ (early mitral flow/early annular velocity ratio); and C – LA remodeling expressed by MR severity, LA volume and PASP (all differences among RV dysfunction subgroups are significant-non parametric-Kruskal-Wallis test)

LVEDV-left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESV-left ventricular end systolic volume; EF-ejection fraction;; DT-deceleration time ; E/A ratio; ; E/E′ ratio ; MR-mitral regurgitation; LA-left atrial., PASP-pulmonary artery systolic pressure; RV-right ventricular

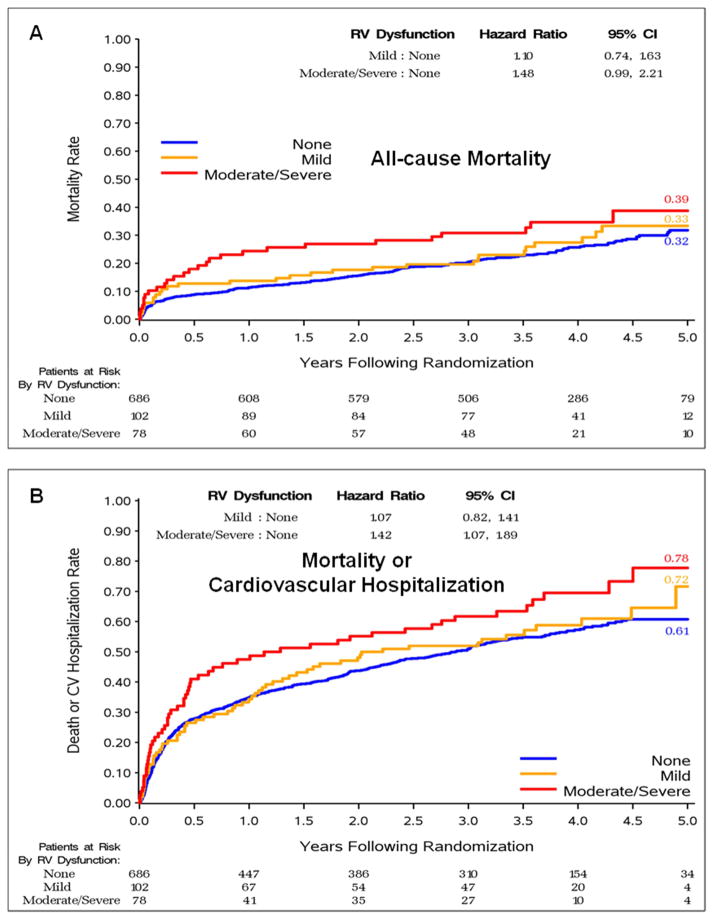

Figure 3.

Impact of the Coexisting RV Dysfunction on Long-term Outcome in the Analyzed Cohort of STICH Patients (n=866) – Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Event Rate by RV Dysfunction Status

RV-right ventricular

Prognostic Role of RV Dysfunction

The prognostic effect of RV dysfunction (independent of treatment) was significant for the short-term outcome of 30-day mortality (p=0.023) and for the long-term outcome of death or CV hospitalization (p=0.022). The relationship with long-term mortality did not achieve conventional significance (p=0.070) (Table 3). The nature of these relationships is illustrated with Kaplan-Meier estimates of event rates by degree of RV dysfunction (Figure 3), where the highest event rates (worst outcomes) are observed in the patients with moderate to severe RV dysfunction. However, the relationship of RV dysfunction with each of the clinical outcomes considered was no longer significant after adjusting for LVEF and even less so after adjusting for LVEF plus the other prognostic clinical and echo factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prognostic Significance of RV Dysfunction and the Interactive Effect of RV Dysfunction and Treatment – Univariate and Multivariable Assessments

| Endpoints | Main Effect of RV Dysfunction | Interaction of RV Dysfunction and Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-adjusted | Adjusted for LVEF | Adjusted for All Prognostic Clinical and Echo Factors1 | Non-adjusted | Adjusted for LVEF | Adjusted for All Prognostic Clinical and Echo Factors1 | |

| Death within 30 Days after Surgery2 (N=848, Events=45) | 0.023 | 0.164 | 0.672 | 0.096 | 0.152 | 0.131 |

| All-cause Death (N=866, Events=239) | 0.070 | 0.632 | 0.711 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.022 |

| Death or Cardiovascular Hospitalization (N=866, Events=506) | 0.022 | 0.281 | 0.838 | 0.013 | 0.041 | 0.302 |

Prognostic factors identified from previous modeling analyses were used as adjustment variables for the three different endpoints. Atrial flutter/fibrillation, age, mitral regurgitation, creatinine, hemoglobin, end-systolic volume index, and LVEF were included in the adjustment for all three endpoints. In addition to the factors listed above, previous MI, previous stroke, and NYHA heart failure class were included for both the death endpoint and the death or cardiovascular hospitalization endpoint. CCS angina class was also included in the model for death within 30 days after surgery. Diabetes and hyperlipidemia were also included in the death model. The ability to perform the 6-minute walk test was also included in the death or cardiovascular endpoint model.

Only patients who actually underwent surgery are included in the analysis of deaths within 30 days after surgery.

Bold values -p<0,05

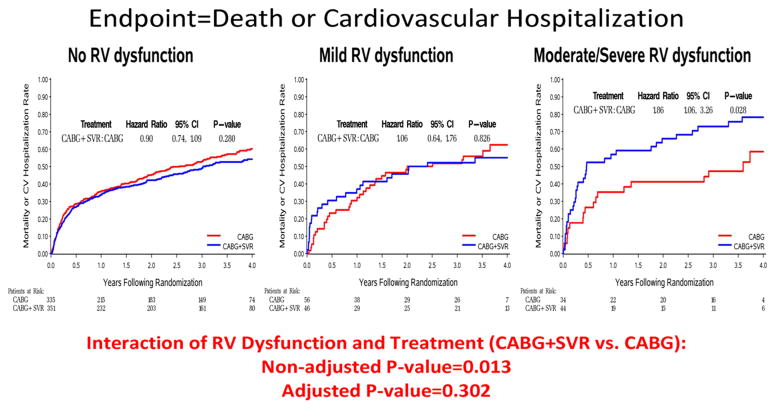

Impact of RV Dysfunction on the Treatment Effect of CABG vs. CABG + SVR

For patients with normal or mildly reduced RV function, the outcomes of CABG alone compared to CABG + SVR were not significantly different for either the primary (death or CV hospitalization) or the secondary (death) endpoints (Figures 4A and 4B). However, when RV function was moderately or severely reduced, there were significantly higher event rates for CABG + SVR compared to CABG alone for death or CV hospitalization (p=0.028) and also for death alone (p=0.005) (Figures 4A and 4B). There was a statistically significant interaction between RV dysfunction and treatment for the composite endpoint of death or CV hospitalization (p=0.013) and for death alone (p=0.001) due to the markedly higher incidence of clinical outcomes among the patients with moderate/severe RV dysfunction who received CABG + SVR. For the death endpoint, the interaction remained significant even after adjusting for all the other prognostic factors (p=0.022) (Table 3). There also was a worsening trend for CABG + SVR with respect to the short-term outcome of surgical death (30-day mortality). Thirty-day mortality among patients with moderately or severely reduced RV function was 5.9% in CABG alone and 13.6% in CABG + SVR, whereas the corresponding 30-day mortality rates among patients with no or mild RV dysfunction were 5.0% for CABG and 4.7% for CABG + SVR.

Figure 4.

Figure 4A. Interaction of RV Dysfunction and Treatment Allocation – Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Event Rate by Treatment Group and LV Dysfunction Groups

SVR-surgical ventricular reconstruction, CABG-coronary artery bypass grafting; RV-right ventricular

Figure 4B. Interaction of RV Dysfunction and Treatment Allocation – Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Event Rate by Treatment Group and LV Dysfunction Groups

SVR-surgical ventricular reconstruction, CABG-coronary artery bypass grafting; RV-right ventricular

Discussion

Prevalence of RV Dysfunction and Its Association with LV Remodeling in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

This is the largest study to evaluate the prevalence and determinants of RV dysfunction in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. In the STICH population, 21% of patients had some degree of RV dysfunction and 9% had moderate or severe dysfunction. Progressively more advanced LV remodeling (larger LV volumes, lower EF, and more severe mitral regurgitation) and worse LV hemodynamic profiles were associated with increasing RV dysfunction. LV systolic and diastolic function parameters, as well as severity of mitral regurgitation, were progressively worse with increasing severity of RV systolic dysfunction..

Mechanisms of RV Dysfunction in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

Several potential underlying mechanisms may explain why progressive RV dysfunction is often accompanied by increasing LV dysfunction (15). RV dysfunction may reflect primary left ventricular, left atrial, or mitral valve pathology (16,17) mediated through direct RV compression and the mechanism of RV/LV interdependence or through increased pulmonary pressures and RV after load due to LV dysfunction (18,19). Alternatively, both ventricles might be affected by the same underlying pathological process (CAD) (20). However, the fact that pulmonary artery systolic pressure was found to increase progressively with worsening of RV systolic function suggests that RV dysfunction is related to functional and hemodynamic abnormalities of the LV. This notion is also supported by a recent study of Verhaert (21). Although many studies have shown that RV dysfunction is a predictor for a poor clinical outcome in patients with HF and reduced LVEF(22), our study is one of the first to demonstrate a relationship between the degree of LV remodelling and the severity of RV dysfunction. The RV is increasingly being recognized as a potential therapeutic target in patients with chronic HF (23). Although not studied extensively, ACE inhibitors (24) and beta-blockers (25) appear to improve RV function. Specific therapies targeted indirectly at RV dysfunction in chronic HF have provided disappointing results (26). Data from Verhaert, et al. suggest that RV function may improve when LV abnormalities are treated (21).

RV Dysfunction and SVR

The long-term outcome of the patients who received CABG + SVR in STICH was adversely affected when RV function was at least moderately reduced at baseline. The abrupt reduction in LV size and volume may have increased diastolic stiffness and aggravated diastolic function and filling pressure, especially when LV filling pressure was already markedly elevated at baseline in patients with RV dysfunction. Contrary to the initial belief, we have demonstrated that SVR appears to have a greater benefit in patients with an early stage of ischemic cardiomyopathy and less benefit, or even harm, in the patients with a more advanced cardiomyopathy and a larger LV (27). The worse outcome of SVR in the setting of advanced RV dysfunction confirms the earlier report of worse outcome of SVR in patients with a larger LV and more reduced EF associated with RV dysfunction.

RV Function Assessment

Many indicators of RV contractility have been proposed (RVEF, RVFAC, TAPSE, strain, strain rate, RVPMI, dP/dT max, RV wall motion analysis, tricuspid annular systolic velocity, maximal RV elastance, Tei index (17), but there is no recognized gold standard imaging modality or parameter for assessment of RV function (28–32). Among the numerous quantitative RV parameters studied by Verhaert, et al., only RV systolic strain was predictive of clinical outcome (21). De Groote at al showed radionuclide RVEF but not TAPSE to be the independent predictor of cardiac survival (22). TAPSE, RV Tei index, RVFAC, and tricuspid systolic annulus velocity were not predictive of long-term outcome (33), however in SAVE trial RVFAC has been shown an independent predictor of mortality and the development of heart failure in patients with known LV dysfunction (34). Although the optimal method of assessment of RV function is not yet clear (35), the visually and qualitatively assessed RV function utilized in our study performed well as it related to outcome.

Study Limitations

In our study, moderate to severe RV dysfunction was found in only 9% of the study patients. This may underestimate the true prevalence of the degree of RV dysfunction since patients with significant RV dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension might have been excluded by study investigators or surgeons because of a perceived high risk for an operation. The evaluation of RV function that we used was a visual assessment. It is difficult to categorize visual assessment, and our classification may not be easily translated to other laboratories. However, differentiation of severe RV dysfunction from normal function is relatively easy by visual assessment. More difficult is to determine mild and moderate RV dysfunction. However, we believe that our observations are clinically relevant as this visual method is the most practical technique in “real life” practice in almost all echocardiography laboratories. Although the visual assessment of RV function in our study was shown to correlate well with RV fractional area change, fractional area change was measured after the completion of the trial and once the study results with visual assessment were known. This limitation notwithstanding, the measurements of RV fractional area change were performed by blinded readers. Also, as a significant proportion of patients could not have RV fractional area change reliably calculated, it may be that visual assessment, the measure used in this study is the most widely applicable technique for evaluation of RV function in the general population of patients such as those in the STICH trial.

Conclusions

In patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, RV dysfunction is associated with more advanced LV remodeling, and hemodynamic abnormalities (larger LV volumes, lower EF, higher filling pressure, and more severe MR). The interaction between RV dysfunction and treatment is significant for mortality after carefully adjusting for other prognostic clinical and echo factors. When baseline RV function is moderately to severely reduced, the addition of SVR to CABG appears to worsen long-term survival compared to the use of CABG alone.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Vanessa Moore for her continuous support and invaluable assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

Funding sources

The Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland: U01HL69015, U01HL69013, and U01HL69010

Abbreviations

- LV

left ventricle

- RV

right ventricle

- EF

ejection fraction

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- HF

heart failure

- LA

left atrium

- SVR

surgical ventricular reconstruction

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CV

cardiovascular

- PASP

pulmonary artery systolic pressure

- ACE-inhibitor

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- PDE5-inhibitor

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor

- RV MPI

right ventricular myocardial performance index

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Racine is a consultant for Forest Laboratories Canada Inc. and a member of the Speakers Bureau of Servier Canada Inc.;.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baker BJ, Wilen MM, Boyd CM, Dinh H, Franciosa JA. Relation of right ventricular ejection fraction to exercise capacity in chronic left ventricular failure. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:596–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Salvo TG, Mathier M, Semigran MJ, Dec GW. Preserved right ventricular ejection fraction predicts exercise capacity and survival in advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1143–53. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00511-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Groote P, Millaire A, Foucher-Hossein C, Nugue O, Marchandise X, Ducloux G. Lablanche JMRight ventricular ejection fraction is an independent predictor of survival in patients with moderate heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:948–54. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polak JF, Holman BL, Wynne J, Colucci WS. Right ventricular ejection fraction: an indicator of increased mortality in patients with congestive heart failure associated with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2:217–24. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavazzi A, Berzuini C, Campana C, Inserra C, Ponzetta M, Sebastiani R, Ghio S, Recusani F. Value of right ventricular ejection fraction in predicting short-term prognosis of patients with severe chronic heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16:774–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghio S, Gavazzi A, Campana C, Inserra C, Klersy C, Sebastiani R, Arbustini E, Recusani F, Tavazzi L. Independent and additive prognostic value of right ventricular systolic function and pulmonary artery pressure in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:183–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghio S, Recusani F, Klersy C, Sebastiani R, Laudisa ML, Campana C, Gavazzi A, Tavazzi L. Prognostic usefulness of the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion in patients with congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:837–842. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00877-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, O’Connor CM, Oh JK, Bonow RO, Pohost GM, Feldman AM, Mark DB, Panza JA, Sopko G, Rouleau JL, Jones RH. The rationale and design of the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1540–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.05.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dor V, DiDonato M, Sabatier M, Montiglio F, Civaia F RESTORE Group. Left ventricular reconstruction by endoventricular circular patch plasty repair: a 17-year experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;13:435–47. doi: 10.1053/stcs.2001.29966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones RH, Velazquez EJ, Michler RE, Sopko G, Oh JK, O’Connor CM, Hill JA, Menicanti L, Sadowski Z, Desvigne-Nickens P, Rouleau JL, Lee KL. Coronary bypass surgery with or without surgical ventricular reconstruction.; STICH Hypothesis 2 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1705–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zembala M, Michler RE, Rynkiewicz A, Huynh T, She L, Lubiszewska B, Hill JA, Jandova R, Dagenais F, Peterson ED, Jones RH. Clinical characteristics of patients undergoing surgical ventricular reconstruction by choice and by randomization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:499–507l. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas PS, DeCara JM, Devereux RB, Duckworth S, Gardin JM, Jaber WA, Morehead AJ, Oh JK, Picard MH, Solomon SD, Wei K, Weissman NJ. Echocardiographic imaging in clinical trials: American Society of Echocardiography Standards for echocardiography core laboratories: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:755–65. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh JK, Pellikka PA, Panza JA, Biernat J, Attisano T, Manahan BG, Wiste HJ, Lin G, Lee K, Miller FA, Jr, Stevens S, Sopko G, She L, Velazquez EJ. Core lab analysis of baseline echocardiographic studies in the STICH trial and recommendation for use of echocardiography in future clinical trials. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake D, Gupta R, Lloyd SG, Gupta H. Right ventricular function assessment: comparison of geometric and visual method response to short-axis slice summation method. Echocardiography. 2007;24:1013–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, Barst RJ, McGoon MD, Meldrum DR, Dupuis J, Long CS, Rubin LJ, Smart FW, Suzuki YJ, Gladwin M, Denholm EM, Gail DB. Right ventricular function and failure. Report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114:1883–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dini FL, Conti U, Fontanive P, Andreini D, Banti S, Braccini L, De Tommasi SM. Right ventricular dysfunction is a major predictor of outcome in patients with moderate to severe mitral regurgitation and left ventricular dysfunction. Am Heart J. 2007;154:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddad F, Hunt SA, Rosenthal DN, Murphy DJ. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, Part I: Anatomy, physiology, aging, and functional assessment of the right ventricle. Circulation. 2008;117:1436–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damman K, Navis G, Smilde TD, Voors AA, van der Bij W, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Decreased cardiac output, venous congestion and the association with renal impairment in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maekawa E, Inomata T, Watanabe I. Prognostic significance of right ventricular dimension on acute decompensation in left sided heart failure. Int Heart J. 2011;52:119–26. doi: 10.1536/ihj.52.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra RK, Devereux RB, Cohen BE, Whooley MA, Schiller NB. Prediction of heart failure and adverse cardiovascular events in outpatients with coronary artery disease using mitral E/A ratio in conjunction with e-wave deceleration time: the heart and soul study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:1134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhaert D, Mullens W, Borowski A, Popović ZB, Curtin RJ, Thomas JD, Tang WH. Right ventricular response to intensive medical therapy in advanced decompensated heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:340–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.900134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Groote P, Fertin M, Goéminne C, Petyt G, Peyrot S, Foucher-Hossein C, Mouquet F, Bauters C, Lamblin N. Right ventricular systolic function for risk stratification in patients with stable left ventricular systolic dysfunction: comparison of radionuclide angiography to echo Doppler parameters. Eur Heart J. 2012 Nov;33(21):2672–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavazzi A, Ghio S, Scelsi L, Campana C, Klersy C, Serio A, Raineri C, Tavazzi L. Response of the right ventricle to acute pulmonary vasodilatation predicts the outcome in patients with advanced heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Am Heart J. 2003;145:310–6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Packer M, Lee WH, Medina N, Yushak M. Hemodynamic and clinical significance of the pulmonary vascular response to long-term captopril therapy in patients with severe chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;6:635–45. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quaife RA, Christian PE, Gilbert EM, Datz FL, Volkman K, Bristow MR. Effects of carvedilol on right ventricular function in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:247–50. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00874-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, Semigran MJ, Lee KL, Lewis G, LeWinter MM, Rouleau JL, Bull DA, Mann DL, Deswal A, Stevenson LW, Givertz MM, Ofili EO, O’Connor CM, Felker GM, Goldsmith SR, Bart BA, McNulty SE, Ibarra JC, Lin G, Oh JK, Patel MR, Kim RJ, Tracy RP, Velazquez EJ, Anstrom KJ, Hernandez AF, Mascette AM, Braunwald E. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. RELAX Trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1268–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh JK, Velazquez EJ, Menicanti L, Pohost GM, Bonow RO, Lin G, Hellkamp AS, Ferrazzi P, Wos S, Rao V, Berman D, Bochenek A, Cherniavsky A, Rogowski J, Rouleau JL, Lee KL. Influence of baseline left ventricular function on the clinical outcome of surgical ventricular reconstruction in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:39–47. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meluzin J, Spinarová L, Hude P, Krejcí J, Dusek L, Vítovec J, Panovsky R. Combined right ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction represents a strong determinant of poor prognosis in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2005;105:164–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer P, Desai RV, Mujib M, Feller MA, Adamopoulos C, Banach M, Lainscak M, Aban I, White M, Aronow WS, Deedwania P, Iskandrian AE, Ahmed A. Right ventricular ejection fraction < 20% is an independent predictor of mortality but not of hospitalization in older systolic heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155:120–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giovanardi P, Tincani E, Rossi R, Agnoletto V, Bondi M, Modena MGl. Right ventricular function predicts cardiovascular events in outpatients with stable cardiovascular diseases: preliminary results. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7:251–6. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bangalore S, Yao SS, Chaudhry FA. Role of right ventricular wall motion abnormalities in risk stratification and prognosis of patients referred for stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Nov 13;50(20):1981–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Mauro M, Calafiore AM, Penco M, Romano S, Di Giammmarco G, Gallina S. Mitral valve repair for dilated cardiomyopathy: predictive role of right ventricular dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2007 Oct;28(20):2510–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itagaki Sh, Hosseinian L, Varghese R. Right ventricular failure after cardiac surgery: management strategies. Semin Thoracic Surg. 2012;24:188–94. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zornoff LA, Skali H, Pfeffer MA, St John Sutton M, Rouleau JL, Lamas GA, Plappert T, Rouleau JR, Moyé LA, Lewis SJ, Braunwald E, Solomon SD. SAVE Investigators Right ventricular dysfunction and risk of heart failure and mortality after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 May 1;39(9):1450–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: A report from the ASE endorsed by the EAE, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]