Abstract

Blastocystis hominis is a common intestinal parasite found in humans living in poor sanitary conditions, living in tropical and subtropical climates, exposed to infected animals, or consuming contaminated food or water. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of B. hominis in Polish military personnel returning from peacekeeping missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. In total, 1,826 stool samples were examined. Gastrointestinal parasites were detected in 17% of the soldiers. The examined stool samples most frequently contained vacuolar forms of B. hominis (15.3%) and cysts of Entamoeba coli (1.0%) or Giardia lamblia (0.7%). In 97.1% of stool samples from infected soldiers, we observed less than five developmental forms of B. hominis in the field of view (40×). The parasite infections in soldiers were diagnosed in the autumn and the spring. There was no statistical correlation between age and B. hominis infection. Our results show that peacekeeping missions in countries with tropical or subtropical climates could be associated with risk for parasitic diseases, including blastocystosis.

Introduction

Blastocystis hominis (Brumpt, 1912) is a unicellular protozoan found in the large intestine in humans.1 It is currently the predominant parasite found in human stool samples, with a higher prevalence in developing countries (50–60%) than developed countries (about 10% or less).1,2 Highly polymorphic and consisting of many morphological forms, including vacuolar, non-vacuolar, granular, amoeboid, and cyst forms, B. hominis can be transmitted as a cyst by the fecal–oral route, particularly in poor hygienic conditions.1,3 It can be found both in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed individuals; for example, Abdel-Hameed and Hassanin4 found this parasite in 73.1% of immunocompetent patients and 26.9% of immunocompromised patients.

The epidemiology, life cycle, and pathogenesis of B. hominis are still poorly known.5 Although this protozoan is a non-pathogenic commensal, both in vivo and in vitro studies have shown its pathogenic power.6,7 In symptomatic patients, the clinical consequences of B. hominis infection include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, flatulence, weight loss, and acute or chronic diarrhea.8,9

In recent years, armed conflicts have been relatively frequent, especially in areas of the Middle East, during which peacekeepers are being exposed to multiple risks to their health and life, including gastrointestinal protozoan infections.10 The occurrence of parasitic diseases in soldiers is closely related to the epidemiological and sanitary/hygienic situation of the region where the troops are stationed. Likewise, B. hominis infection is associated with poor sanitation levels, tropical and subtropical climates, exposure to animals, and consumption of contaminated food or water. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of B. hominis and other infections of protozoan parasites in soldiers returning from Middle Eastern peacekeeping missions.

Materials and Methods

We examined stool samples from 913 Polish soldiers participating in peacekeeping missions, particularly in Afghanistan and Iraq, in 2008–2010. Stool samples were collected and investigated by direct smear examination two times: one time before leaving and one time after returning. The soldiers were divided into six age groups: ages 16–20 (A1; n = 17), 21–30 (A2; n = 530), 31–40, (A3; n = 316), 41–50 (A4; n = 47), 51–60 (A5; n = 2), and 61–70 years old (A6; n = 1). The research was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin (KB-0012/58/12).

All stool samples from the soldiers were examined for intestinal parasites by Lugol iodine and formalin-ethyl acetate concentration according to the work by Garcia.6 These preparations were examined under both low-power (10×) and high-dry (40×) objectives. The results obtained were analyzed statistically using Statistica 9.0 software (StatSoft Inc.).

Results

Gastrointestinal parasites were observed in 17% of the military personnel returning from peacekeeping missions. The stool samples most frequently contained vacuolar forms of B. hominis (15.3%) and cysts of Entamoeba coli (1.0%) and Giardia lamblia (0.7%). The majority of the B. hominis infections (99.3%) were not accompanied by other parasitic infections. Only one soldier had both B. hominis and E. coli cysts (0.1%). Data are presented in Table 1. We found no correlation between age and the prevalence of infection.

Table 1.

The prevalence of Blastocystis hominis infection in soldiers returning from missions in each age group

| Age group | Prevalence of B. hominis | |

|---|---|---|

| n | Percent | |

| A1 (16–20 years; n = 17) | 3 | 17.6 |

| A2 (21–30 years; n = 530) | 67 | 12.6 |

| A3 (31–40 years; n = 316) | 61 | 19.3 |

| A4 (41–50 years; n = 47) | 8 | 17.0 |

| A5 (51–60 years; n = 2) | 0 | 0 |

| A6 (61–70 years; n = 1) | 1 | 100.0 |

| Total | 140 | 15.3 |

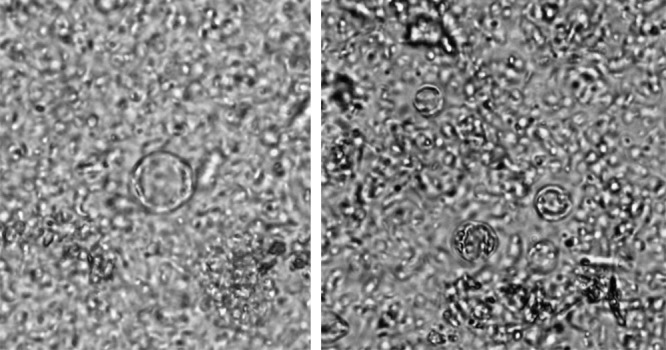

In 136 (97.1%) stool samples from the infected soldiers, less than five morphological forms of B. hominis were observed in the field of view (40×), whereas 4 (2.9%) of the stool samples contained five or more forms (Figure 1). Most of the infected soldiers were diagnosed in the fall (54.3%) and spring (24.3%). In winter and summer testing, the percentages of infected soldiers with B. hominis were lower: 9.3% and 12.1%, respectively.

Figure 1.

The vacuolar form Blastocystis hominis in stool (40× magnification).

Discussion

In this study, 15% of the stool samples from the soldiers returning from peacekeeping missions in Afghanistan and Iraq contained vacuolar forms of B. hominis, and around 1% each of the stool samples contained E. coli or G. lamblia cysts. By comparison, Buczynski and others,10 who studied the Multinational Corps personnel stationed in Lebanon, reported infections with Trichuris trichiura (17%), Ancylostoma duodenale (16%), G. lamblia (15%), and Ascaris lumbricoides (9%).

A similar prevalence of B. hominis infection to this study had been found in Thai soldiers (15%) in one study,11 whereas a higher prevalence of B. hominis infection had been observed in stool samples in 37%12 of Thai soldiers in another study and 44%13 of military personnel as well as 36%14 of the local population of Honduras. The difference in prevalence of B. hominis infections between these populations may be caused by the different diagnostic methods used7 as well as the soldiers being stationed in different areas under different sanitary conditions.

In some studies the prevalence of B. hominis infection was higher in children than adults.15–17 However, in this study, we found no statistically significant relationship between age and B. hominis infection.

In the literature, when stool samples contained less than five forms of B. hominis in the field of view (40×), patients usually experienced no symptoms.18 In our study, most of the soldiers showed no gastric symptoms, which could have been caused by low parasitemia.

The occurrence of parasitic diseases in peacekeeping missions is closely related to the epidemiological and sanitary–hygienic situation of the region where the troops are stationed. This study shows that parasitic infection acquired through the fecal–oral route from contaminated water and food is still a significant problem among military personnel. Despite the prevalence of parasitic infections among the peacekeepers being low, mostly because of the effective preventative health program, peacekeeping missions in countries with tropical or subtropical climates are still associated with the risk of parasitic protozoan diseases, including blastocystosis.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Aleksandra Duda, Danuta Kosik-Bogacka, Natalia Lanocha-Arendarczyk, and Lidia Kołodziejczyk, Department of Biology and Medical Parasitology, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland, E-mails: aleksandra_duda@interia.pl, kodan@pum.edu.pl, nlanocha@pum.edu.pl, and lkolo@pum.edu.pl. Aleksandra Lanocha, Clinic of Haematology, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland, E-mail: aleksandra.lanocha@o2.pl.

References

- 1.Stenzel DJ, Boreham PF. Blastocystis hominis revisited. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:563–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jantermtor S, Pinlaor P, Sawadpanich K, Pinlaor S, Sangka A, Wilailuckana C, Wongsena W, Yoshikawa H. Subtype identification of Blastocystis spp. isolated from patients in a major hospital in northeastern Thailand. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:1781–1786. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle PW, Helgason MM, Mathias RG, Proctor EM. Epidemiology and pathogenicity of Blastocystis hominis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:116–121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.1.116-121.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Hameed DM, Hassanin OM. Proteaese activity of Blastocystis hominis subtype 3 in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotez P. The other intestinal protozoa: enteric infections caused by Blastocystis hominis, Entamoeba coli, and Dientamoeba fragilis. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2000;11:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia LS. Intestinal protozoa: Amebae. In: Garcia LS, editor. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2007. pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts T, Barratt J, Harkness J, Ellis J, Stark D. Comparison of microscopy, culture, and conventional polymerase chain reaction for detection of Blastocystis sp. in clinical stool samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:308–312. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taşova Y, Sahin B, Koltaş S, Paydaş S. Clinical significance and frequency of Blastocystis hominis in Turkish patients with hematological malignancy. Acta Med Okayama. 2000;54:133–136. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rene BA, Stensvold CR, Badsberg JH, Nielsen HV. Subtype analysis of Blastocystis isolates from Blastocystis cyst excreting patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:588–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buczynski A, Korzeniewski K, Bzdega I, Jerominko A. Infectious diseases among persons from catchment area of the hospital of the United Nations interim force in Lebanon, from 1993 to 2000. Przegl Epidemiol. 2004;58:303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leelayoova S, Siripattanapipong S, Naaglor T, Taamasri P, Mungthin M. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in military personnel and military dogs, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:S53–S59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leelayoova S, Rangsin R, Taamasri P, Naaglor T, Thathaisong U, Mungthin M. Evidence of waterborne transmission of Blastocystis hominis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:658–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taamasri P, Leelayoova S, Rangsin R, Naaglor T, Ketupanya A, Mungthin M. Prevalence of Blastocystis hominis carriage in Thai army personnel based in Chonburi, Thailand. Mil Med. 2002;167:643–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwa BH, Aviles R, Tucker MS, Sanchez JA, Isaza MG, Nash BN, Price DL, DeBaldo AC, Stockton MB, Fennell EM. Surveillance for enteric parasites among U.S. military personnel and civilian staff on Joint Task Force Base-Bravo in Soto Cano, Honduras and the local population in Comayagua and La Paz, Honduras. Mil Med. 2004;169:903–908. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.11.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nimri LF. Evidence of an epidemic of Blastocystis hominis infections in preschool children in northern Jordan. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2706–2708. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2706-2708.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martín-Sanchez AM, Canut-Blasco A, Rodríguez-Hernandez J, Montes-Martínez I, García-Rodríguez JA. Epidemiology and clinical significance of Blastocystis hominis in different population groups in Salamanca (Spain) Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8:553–559. doi: 10.1007/BF00146376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angelov I, Lukanov T, Tsvetkova N, Petkova V, Nicoloff G. Clinical, immunological and parasitological parallels in patients with blastocystosis. J of IMAB. 2008;1:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan DJ, Raucher BG, McKitrick JC. Association of Blastocystis hominis with signs and symptoms of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:548–550. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.4.548-550.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]