Abstract

Purpose

In search of reliable biologic markers to predict the risk of normal tissue damage by radio(chemo)therapy before treatment, we investigated the association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the transforming growth factor 1 (TGFβ1) gene and risk of radiation pneumonitis (RP) in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Patients and Methods

Using 164 available genomic DNA samples from patients with NSCLC treated with definitive radio(chemo)therapy, we genotyped three SNPs of the TGFβ1 gene (rs1800469:C-509T, rs1800471:G915C, and rs1982073:T869C) by polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism method. We used Kaplan-Meier cumulative probability to assess the risk of grade ≥ 3 RP and Cox proportional hazards analyses to evaluate the effect of TGFβ1 genotypes on such risk.

Results

There were 90 men and 74 women in the study, with median age of 63 years. Radiation doses ranging from 60 to 70 Gy (median = 63 Gy) in 30 to 58 fractions were given to 158 patients (96.3%) and platinum-based chemotherapy to 147 (89.6%). Grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 RP were observed in 74 (45.1%) and 36 patients (22.0%), respectively. Multivariate analysis found CT/CC genotypes of TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C to be associated with a statistically significantly lower risk of RP grades ≥ 2 (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.489; 95% CI, 0.227 to 0.861; P = .013) and grades ≥ 3 (HR = 0.390; 95% CI, 0.197 to .774; P = 0.007), respectively, compared with the TT genotype, after adjustment for Karnofsky performance status, smoking status, pulmonary function, and dosimetric parameters.

Conclusion

Our results showed that CT/CC genotypes of TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C gene were associated with lower risk of RP in patients with NSCLC treated with definitive radio(chemo)therapy and thus may serve as a reliable predictor of RP.

INTRODUCTION

Studies by us1,2 and others1,3–6 showed that radiation dose distribution to normal lung during non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) radiotherapy affects radiation pneumonitis (RP) risk. These studies identified associations between mean lung dose (MLD) and lung volume exposed to doses exceeding a threshold (VDose), such as V20, and the RP incidence. Dosimetric parameters can be determined before radiotherapy and incorporated into normal-tissue complication models to guide plan modification for individual patients.7,8 Recently, we found smoking status to be predictive of RP risk, independent of dosimetric effects.9–10 However, only a percentage of patients in whom normal lung is exposed to a certain dose and volume of irradiation develop RP even after stratifying for smoking status,10 suggesting that patient genetic makeup may play a critical role in individual's response to radiotherapy and RP development. Because there are no reliable biologic factors to predict RP risk, standard radiation doses are limited by the most sensitive patients' tolerance.

Because inflammatory cytokines are involved in RP, there have been significant research efforts to identify specific cytokines as risk-predicting biomarkers. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) is one of the most extensively studied cytokines. Animal and human studies suggest a particularly important role of TGFβ1 in the development of radiation lung injury.11–14 TGFβ1 can trigger a wide diversity of responses, depending on the genetic makeup and environment of the target cells.15 Dysregulation of the TGFβ pathway and mutations in the genes encoding for TGFβ, its receptor, or the associated intracellular signaling molecules are important in the pathogenesis of many diseases.15–17

Plasma values of TGFβ1 are often elevated during radiotherapy in patients who developed RP.11,18,19 However, reports on the predictive value of TGFβ1 for RP risk are inconsistent.4,12,20,21 Some researchers reported that the return of plasma TGFβ1 levels to normal after radiotherapy accurately predicted that patients would not develop RP,11 but others failed to confirm this finding.19,20,22,23 Additionally, there is concern that TGFβ1 can be produced by both tumor and normal tissues, and numerous factors, including improper handling of blood samples or inadequate centrifugation conditions, can falsely increase the calculated level of circulating TGFβ1.24 Furthermore, measuring TGFβ1 at 4 weeks after radiation starts would provide information only after the damage to normal lung had been done, which seriously limits this approach for risk prediction.

The plasma concentration of TGFβ1 is predominantly under genetic control,25 and recent studies demonstrate a strong association between polymorphisms in the TGFβ1 gene and skin fibrosis in patients with breast cancer and gynecologic cancers after radiotherapy.26–28 Our study investigates whether differences in TGFβ1 genotypes are associated with RP differences in patients with NSCLC who receive definitive radio(chemo)therapy and whether genotyping of TGFβ1 could predict RP risk before radiotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

We identified 164 patient DNA samples available from a data set of 576 NSCLC patients who were treated with definitive radiation at our institution between 1999 and 2005. The median total radiation dose was 63 Gy (range, 50.4 to 84.0 Gy) at 1.2 to 2 Gy/fraction (35% [n = 58] of patients had 1.2 Gy/fraction twice a day to 69.6 Gy/58 fractions); 96.3% of patients received 60 to 70 Gy, and 89.6% (n = 147) of patients received platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy. Therapies received by this cohort included induction chemotherapy followed by radiation (n = 15), induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy and radiation (n = 48), and upfront concurrent chemotherapy and radiation without induction treatment (n = 84). Seventeen patients were treated with radiation only. The details of the radiation treatment planning, follow-up schedule and tests, guideline for RP scoring, and dosimetric data analysis were described in our previous publications.1,9 This investigation was approved by The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board. We complied with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

Genotyping Methods

A leukocyte cell pellet was obtained from the buffy coat by centrifugation of 1 mL of whole blood and used for DNA extraction. A Qiagen DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to obtain genomic DNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA purity and concentration were determined by spectrophotometric measurement of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm, respectively.

We searched the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Genome Program geneSNPs database and related literature to identify all functional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the TGFβ1 gene with a minor allele frequency more than 0.05 in a white population.29 We selected three genotype SNPs of the TGFβ1 gene that met at least two of three criteria:1 a minor allele frequency of at least 5%,2 location in the promoter untranslated region or coding region of the gene, and3 previous reports of an association with lung or other cancers. We genotyped the SNPs of the TGFβ1 gene: rs1800469:C-509T, rs1800471:G915C, and rs1982073:T869C by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) restriction fragment-length polymorphism method. PCR-based assays were used to amplify the fragments that contained TGFβ1 polymorphisms. The primers were designed to create new restriction sites and used to amplify the target fragments of TGFβ1 rs1800469, rs1800471, and rs1982073, respectively. The sequences of the primers used for the genotyping assays were as follows: 5′-GTC GCA GGG TGT TGA GT GAC AG-3′ and 5′-AGG GGG CAA CAG GAC ACC TTA-3′ for rs1800469, 5′-TAC TGG TGC TGA CGC CGG GCC-3′ and 5′-CTT GGA CAG GAT CTG GCC GCG G-3′ for rs1800471, and 5′-CTC CGG GCT GCG GCT GCA GC-3′ and 5′-GGC CTC GAT GCG CTT CCG CTT CA-3′ for rs1982073. The PCR profile consisted of an initial melting step of 95°C for 5 minutes, 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 minutes. These primers generated PCR products of 123 base pairs (bp), 116 bp, and 136 bp that were digested by the AflII, ApaI, and PvuII (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), respectively, to identify genotypes for the rs1800469 promoter C509T, TGFβ1 rs1800471 exon1 G915C(Arg25Pro), and rs1982073 exon1 T869C(Leu10Pro), respectively. The PCR generated 101-bp and 22-bp fragments of the rs1800469 T allele, 95-bp and 21-bp fragments of the rs1800471 C allele, and 117-bp and 19-bp fragments of the rs1982073 T allele. The genotyping assays of 10% of the samples were repeated, and the results were 100% concordant.

Statistical Analysis

The end points (ie, development of RP grade ≥ 2 or grade ≥ 3) were assessed and scored using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0.30 The times to end points development were calculated from radiotherapy start; patients not experiencing the end point were censored at the last follow-up.

Patients were grouped according to their genotypes. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and CI to evaluate the influence of genotypes on RP risk. In addition, multivariate Cox regression was performed to adjust for other covariates. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to estimate the cumulative RP probability. Likelihood ratio tests were performed for each multivariate Cox regression to assess the goodness-of-fit. A P value of .05 or less was considered statistically significant in a two-sided t test.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

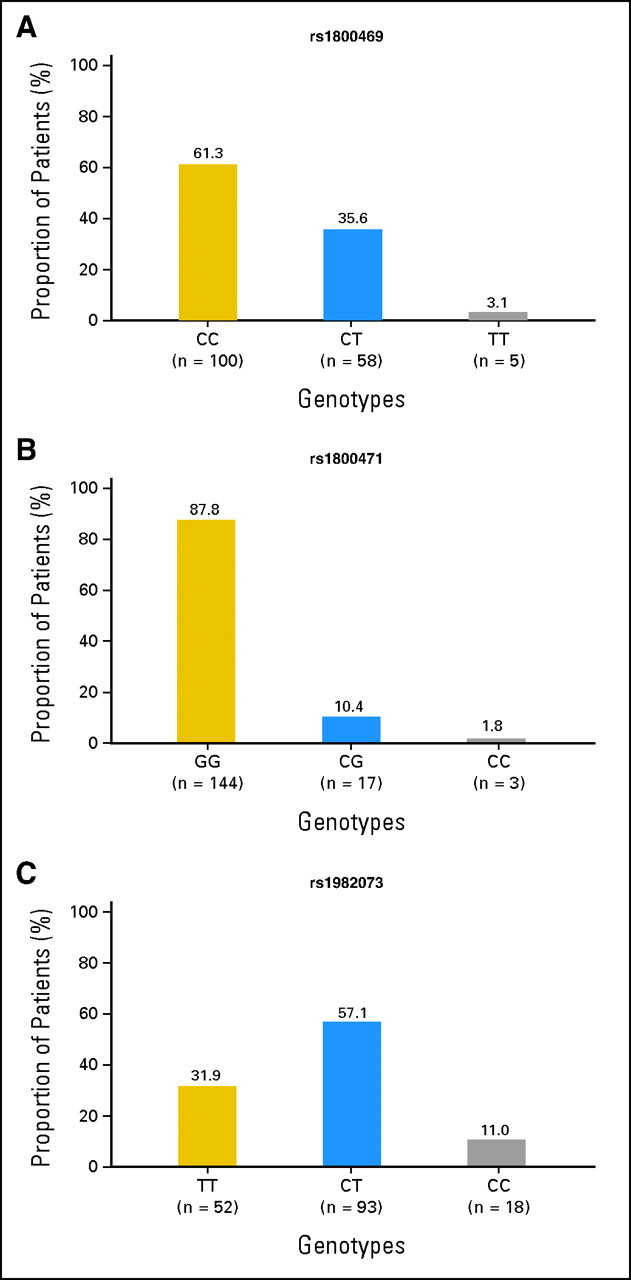

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the 164 patients. There were 90 men and 74 women, with median age of 63 years (range, 35 to 83 years). Among them, 77.4% were white, 81.1% had stage III disease, 89.6% were treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and 96.3% received radiation doses between 60 and 70 Gy (median, 63 Gy; range, 54 to 84 Gy) with once (1.8-2 Gy/fraction) or twice a day (1.2 Gy/fraction to 69.6 Gy in 58 patients) fractionations. The median MLD was 21 Gy (range, 3 to 37 Gy), and the median V20 was 35% (range, 3% to 63%). Figure 1 shows genotype distribution within the rs1800469:C-509T, rs1800471:G915C, and rs1982073:T869C SNPs of the TGFβ1 gene. The rs1800469:C-509T consisted of CC genotype in 61.3% and CT or TT (CT/TT) genotypes in 35.6% and 3.1% of (n = 163) patients, respectively. The rs1800471:G915C consisted of GG genotype in 87.8% and of CG or CC (CG/CC) genotypes in 10.4% and only 1.8% of patients (n = 164), respectively. The rs1982073:T869C consisted of TT genotype in 31.9% and of CT or CC (CT/CC) genotypes in 57.1% and 11.0% of patients (n = 163), respectively. The frequency in distributions of these TGFβ1 genotypes did not differ by sex, age, race, histology, smoking status, use of chemotherapy, MLD, V20, or tumor radiation dose.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 164)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 90 | 54.9 |

| Female | 74 | 45.1 |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 63 | |

| Range | 35-83 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 127 | 77.4 |

| Black | 27 | 16.5 |

| Other | 10 | 6.1 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 16 | 9.8 |

| II | 9 | 5.5 |

| III | 133 | 81.1 |

| IV | 6 | 3.6 |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell | 52 | 31.7 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 57 | 34.8 |

| NSCLC, NOS | 55 | 33.5 |

| KPS | ||

| 90-100 | 41 | 25.0 |

| 80 | 98 | 59.8 |

| < 80 | 25 | 15.2 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 38 | 23.2 |

| Former | 110 | 67.0 |

| Never | 16 | 9.8 |

| Treatment | ||

| C + RT | 15 | 9.1 |

| C + CRT | 48 | 29.3 |

| CRT | 84 | 51.2 |

| RT | 17 | 10.4 |

| Radiation dose, Gy | ||

| Median | 63 | |

| Range | 54-83 | |

| MLD, n = 154, Gy | ||

| Median | 21 | |

| Range | 3-37 | |

| V20, n = 148, % | ||

| Median | 35 | |

| Range | 3-63 | |

| DLCO-Hb, n = 130, mL/min/mm Hg | ||

| Median | 15.14 | |

| Range | 3.60-31.74 | |

| FEV1, n = 137, L | ||

| Median | 1.96 | |

| Range | 0.56-4.62 | |

Abbreviations: NSCLC, NOS, non–small-cell lung carcinoma, not otherwise specified; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; C, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; CRT, concurrent chemoradiation; MLD, mean lung dose; V20, volume of normal lung receiving 20 Gy or more radiation; DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide of the lung; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Fig 1.

The incidences and distributions of transforming growth factor 1 (TGFβ1) polymorphisms. (A) TGFβ1 rs1800469:C-509T; (B) TGFβ1 rs1800471:G915C; (C) TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C. CC in rs1800469:C-509T, GG in rs1800471:G915C, and TT in rs1982073:T869C are common genotypes.

Radiation Pneumonitis and TGFβ1 SNPs and Genotypes

The median follow-up time for RP of any grade after radio(chemo)therapy was 21 months (range, 1 to 97 months). Table 2 shows the associations between patient-, tumor-, therapy-related characteristics and RP grade ≥ 3 by univariate and multivariate analyses. Karnofsky performance status (KPS) and radiation dosimetric factors had statistically significant associations with RP. Patients with KPS ≤ 80 had a higher RP risk compared with those with KPS more than 80 (P = .010). MLD and V20 were also strongly associated with RP risk, consistent with our previous publications.1,9 However, neither baseline pulmonary function nor smoking status was associated with RP risk in this population.

Table 2.

Associations Between Patient-, Tumor-, and Therapy-Related Characteristics and Grade ≥ 3 Radiation Pneumonitis

| Parameter | Univariate Analysis |

Multivariate Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Male | 0.486 | 0.239 to 0.990 | .047 | 1.180 | 0.361 to 3.875 | .785 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| < 65 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 0.948 | 0.489 to 1.839 | .476 | 1.029 | 0.409 to 2.587 | .952 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Black | 0.889 | 0.346 to 2.336 | .828 | 0.829 | 0.257 to 2.675 | .829 |

| Other | 1.993 | 0.697 to 5.698 | .198 | 2.620 | 0.568 to 12.080 | .217 |

| KPS | ||||||

| 80 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| < 80 | 1.301 | 0.587 to 2.884 | .518 | 1.293 | 0.326 to 5.133 | .714 |

| 90-100 | 0.256 | 0.077 to 0.849 | .026 | 0.066 | 0.008 to 0.534 | .011 |

| Stage | ||||||

| III, IV | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| I, II | 1.109 | 0.461 to 2.664 | .818 | 0.723 | 0.351 to 1.491 | .380 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| NSCLC, NOS | 0.782 | 0.329 to 1.855 | .576 | 1.650 | 0.522 to 5.209 | .394 |

| Squamous cell | 1.533 | 0.717 to 3.276 | .270 | 1.443 | 0.505 to 4.121 | .494 |

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| Current | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Former | 1.642 | 0.678 to 3.977 | .272 | 2.037 | 0.645 to 6.435 | .225 |

| Never | 1.428 | 0.357 to 5.711 | .615 | 0.520 | 0.049 to 5.549 | .588 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 1.011 | 0.340 to 3.611 | .866 | 0.617 | 0.109 to 3.477 | .584 |

| CRT | ||||||

| Yes | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 1.404 | 0.660 to 2.985 | .378 | 1.735 | 0.414 to 7.270 | .451 |

| Radiation dose, Gy | ||||||

| 63-66 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| > 66 | 1.209 | 0.501 to 2.915 | .673 | 1.737 | 0.528 to 5.717 | .363 |

| < 63 | 0.787 | 0.376 to 1.648 | .526 | 0.327 | 0.095 to 1.124 | .076 |

| MLD, Gy* | ||||||

| < 15 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 15-25 | 3.118 | 1.074 to 9.052 | .037 | 4.324 | 1.349 to 73.157 | .024 |

| > 25 | 3.326 | 1.034 to 10.928 | .044 | 10.358 | 1.866 to 57.486 | .008 |

| V20 | ||||||

| < 30% | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 30-40% | 3.345 | 1.213 to 9.787 | .020 | 10.249 | 1.869 to 56.198 | .007 |

| > 40% | 3.589 | 1.323 to 9.732 | .012 | 9.006 | 2.185 to 37.132 | .002 |

| DLCO, mL/min/mm Hg | ||||||

| ≥ 15.14 | 1.00 | 1.000 | ||||

| < 15.14 | 0.693 | 0.318 to 1.510 | .356 | 0.623 | 0.195 to 1.991 | .425 |

| FEV1, L | ||||||

| ≥ 1.96 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| < 1.96 | 0.811 | 0.386 to 1.706 | .582 | 0.489 | 0.148 to 1.617 | .241 |

NOTE. Multivariate analyses were adjusted for all factors listed in Table.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; NSCLC, NOS, non–small-cell lung carcinoma, not otherwise specified; CRT, concurrent chemoradiation; MLD, mean lung dose; V20, volume of normal lung receiving 20 Gy or more radiation; DLCO, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide of the lung; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Either MLD or V20 was used in multivariate analyses, but not together.

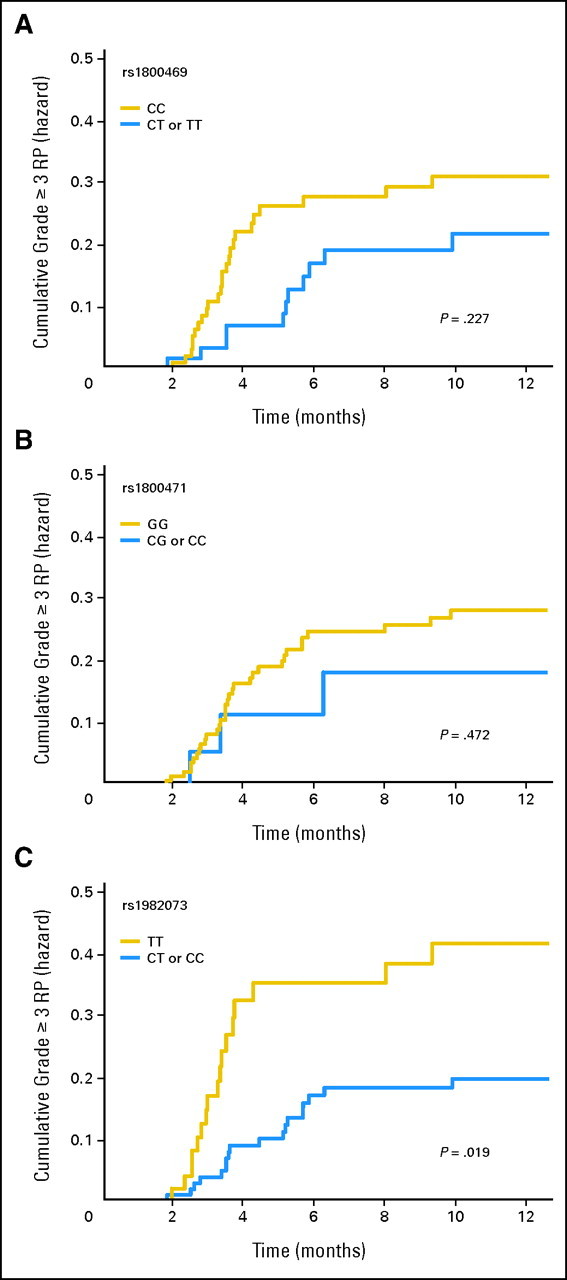

Tables 3 and 4 list the Kaplan-Meier incidences of grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 RP in patients with different TGFβ1 genotypes at 10 months from starting radiation. In general, RP developed more often in patients exhibiting CC in rs1800469:C-509T, GG in rs1800471:G915C, or TT in rs1982073:T869C genotypes, with grade ≥ 3 RP rates of 25.0%, 22.9%, and 32.7%, respectively, than in those having CT/TT in rs1800469:C-509T, CG/CC in rs1800471:G915C, and CT/CC in rs1982073:T869C genotypes, for which the incidences were 17.5%, 15.0%, and 16.2%, respectively. With respect to RP grade ≥ 2, the associations were statistically significant for rs1800469:C-509T and rs1982073:T869C SNPs (P = .022 and P = .013, respectively). However, for RP grade ≥ 3, the association was statistically significant only for rs1982073:T869C SNP (P = .007). In this group, RP developed in 32.7% of patients having TT genotype and in 16.2% of patients having CC/CT genotypes at 10 months after initiation of radiotherapy. Figure 2 plots the incidence of RP grade ≥ 3 as a function of time for each TGFβ1 genotype. Development of RP grade ≥ 3 seems to be delayed, and the incidence remained lower in the CT/TT in rs1800469:C-509T, CG/CC in rs1800471:G915C, and CT/CC in rs1982073:T869C genotypes; however, this was statistically significant only in patients with CT/CC genotype in rs1982073:T869C (P = .019; Fig 2C). The same analyses were performed for RP grade ≥ 2, and the results and conclusions were the same as for grade ≥ 3 RP (data not shown).

Table 3.

Associations Between TGFβ1 Genotypes and Grade ≥ 2 Radiation Pneumonitis

| Polymorphisms and Genotypes | No. of Events | No. Total | Univariate Analysis |

Multivariate Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||

| TGFβ1 rs1800469:C-509T | ||||||||

| CC | 47 | 100 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| CT or TT | 27 | 63 | 0.883 | 0.549 to 1.421 | .609 | 0.633 | 0.427 to 0.937 | .022 |

| TGFβ1 rs1800471:G915C | ||||||||

| GG | 65 | 144 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| CG or CC | 9 | 20 | 0.993 | 0.494 to 1.994 | .984 | 1.125 | 0.510 to 2.482 | .771 |

| TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C | ||||||||

| TT | 30 | 52 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| CT or CC | 44 | 111 | 0.568 | 0.356 to 0.905 | .017 | 0.489 | 0.227 to 0.861 | .013 |

NOTE. Multivariate analyses in this table were adjusted for Karnofsky performance status, mean lung dose, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, and smoking status. Similar results were obtained when multivariate analyses were adjusted for all the factors listed in Table 1 (data not shown).

Abbreviations: TGFβ1, transforming growth factor 1; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 4.

Associations Between TGFβ1 Genotypes and Grade ≥ 3 Radiation Pneumonitis

| Polymorphism and Genotype | No. of Events | No. Total | Univariate Analysis |

Multivariate Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||

| TGFβ1 rs1800469:C-509T | ||||||||

| CC | 25 | 100 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| CT or TT | 11 | 63 | 0.648 | 0.319 to 1.318 | .231 | 0.526 | 0.254 to 1.091 | .085 |

| TGFβ1 rs1800471:G915C | ||||||||

| GG | 33 | 144 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| CG or CC | 3 | 20 | 0.651 | 0.200 to 2.122 | .476 | 1.050 | 0.313 to 3.528 | .937 |

| TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C | ||||||||

| TT | 17 | 52 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| CT or CC | 18 | 111 | 0.445 | 0.229 to 0.864 | .017 | 0.390 | 0.197 to 0.774 | .007 |

NOTE. Multivariate analyses in this table were adjusted for Karnofsky performance status, mean lung dose, and smoking status. Similar results were obtained when multivariate analyses were adjusted for all the factors listed in Table 1 (data not shown).

Abbreviations: TGFβ1, transforming growth factor 1; HR, hazard ratio.

Fig 2.

Cumulative probability of radiation pneumonitis (RP) grades ≥ 3 as a function of time from the start of radiation therapy by genotypes. (A) TGFβ1 rs1800469:C-509T; (B) TGFβ1 rs1800471:G915C; (C) TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C. The TT genotype TGFβ1 rs1982073 T869C was associated with a statistically significant higher incidence of RP compared with other genotypes.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

Univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses of the data for grade ≥ 2 and grade ≥ 3 RP showed that CT/CC rs1982073:T869C genotypes were associated with a decreased risk of RP development (for grade ≥ 2 RP, HR = 0.568, 95% CI, 0.356 to 0.905, P = .017; for grade ≥ 3 RP, HR = 0.445, 95% CI, 0.229 to 0.864, P = .017, respectively; Tables 3 and 4). This effect was virtually unchanged after adjustment for KPS, smoking status, forced expiratory volume in 1 second and V20, or MLD by multivariate analysis (for grade ≥ 2 RP, HR = 0.489, 95% CI, 0.227 to 0.861, P = .013; for grade ≥ 3 RP, HR = 0.390, 95% CI, 0.197 to 0.774, P = 0.007), suggesting that the association between cumulative RP incidence rate and rs1982073:T869C SNP is an independent factor (Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore, we performed multivariate analyses with adjustment for all the patient-, tumor-, and therapy-related characteristics listed in Table 1 and obtained similar results for RP grades ≥ 2 and grades ≥ 3 (data not shown).

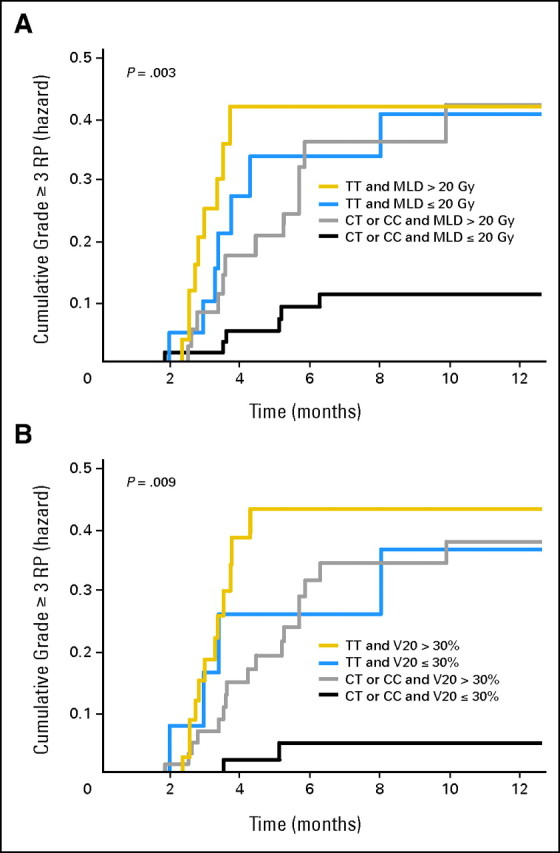

Dosimetric Factors

Figure 3A shows the cumulative RP grade ≥ 3 probability as a function of time according to genotype and MLD. Patients with CT/CC genotypes in rs1982073:T869C who received an MLD ≤ 20 Gy had a lower RP incidence than patients with an MLD ≤ 20 Gy with TT genotypes in rs1982073:T869C (P = .003). We also analyzed the cumulative RP grade ≥ 3 probability as a function of time according to genotypes and V20 (Fig 3B). Patients with CT/CC genotypes in rs1982073:T869C who had V20 ≤ 30% of their normal lung volume had a lower incidence of RP grade ≥ 3 than patients with a V20 ≤ 30% with TT genotype in rs1982073 (P = .009). However, this difference was not significant in patients who received MLD more than 20 Gy (Fig 3A) or V20 more than 30% (Fig 3B), suggesting that the effect of the dosimetric parameters on RP grade ≥ 3 was independent of genetic predisposition. The same analyses were performed for RP grade ≥ 2, and the results and conclusions remain unchanged (data not shown).

Fig 3.

The effects of single nucleotide polymorphism at TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C and dosimetric parameters on the cumulative incidence of radiation pneumonitis (RP) grades ≥ 3. (A) Patients with the (CT or CC) genotypes of TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C and mean lung dose (MLD) ≤ 20 Gy had a statistically significant lower incidence of RP grades ≥ 3 compared with TT genotype. (B) Patients with the (CT or CC) genotypes of TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C and volume of normal lung receiving 20 Gy or more radiation (V20) ≤ 30% had a statistically significant lower incidence of RP grades ≥ 3 compared with TT genotype. This association between TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C and RP grades ≥ 3 is independent of the MLD or V20.

DISCUSSION

The data from our study demonstrated that patients having rs1800469:C-509T, rs1800471:G915C, and rs1982073:T869C alleles of the TGFβ1 gene had a lower RP probability after radiotherapy for NSCLC, and significantly so with rs1982073:T869C. The association between CT/CC genotypes in rs1982073:T869C gene and lower RP risk was independent of V20 and MLD. We were able to identify a group of patients with the lowest RP risk (CT/CC genotype in rs1982073:T869C, and MLD < 20 Gy or V20 < 30%). Because this information could be obtained before the radiation initiation, this test could be used, in addition to radiation dosimetric factors, as a predictive biomarker to prescribe personalized radio(chemo)therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that CT/CC genotypes of rs1982073:T869C predict a lower RP risk in patients with lung cancer.

TGFβ1 is a multifunctional growth factor with many different effects on cell proliferation, tissue differentiation, inflammation, and fibrosis.31,32 TGFβ1 possesses a highly polymorphic extensive regulatory region that likely impacts the pathogenesis of numerous TGFβ1-related diseases through altered TGFβ1 expression as a result of the polymorphisms.33 Comprehensive examination of the function and diversity of the TGFβ1 promoter region and exon 1 (−2,665 to +423) have demonstrated that the TGFβ1 alleles are clustered into three phylogenetic groups based on the common functional SNPs c.−1347C>T (commonly known as C-509T) and c.+29T>C (commonly known as T869C), suggesting three phenotypic groups.33 The common TGFβ1 promoter SNP c.−1347C>T (rs1800469:C-509T) has been linked to a nearly two-fold difference in plasma levels of TGFβ1 among individuals and also with the risk, progression, and outcome of numerous diseases. Therefore, it has been suggested that the molecular mechanism for the difference in TGFβ1 plasma levels linked to −1347C is due to transcriptional suppression by activator protein 1 binding to −1347C.33 SNPs in the TGFβ1 gene are associated with otosclerosis,34 Alzheimer's disease,35 renal allograft rejection,36 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,37,38 lung cancer,36 colorectal neoplasia,39 and invasive breast cancer.40

An animal study reported a dose-dependent induction of TGFβ1 in the lung tissue of fibrosis-prone mice after radiation41; soluble TGFβ1 type II receptor gene therapy reduced the level of active TGFβ1 in tissue, consequently ameliorating acute radiation-induced lung injury.13 Anscher et al11 reported that a normal plasma level of TGFβ1 by the end of radiotherapy was more common in patients without RP. A return of the plasma TGFβ1 to its normal level accurately identified patients who would not develop RP.11,42 Changes in plasma TGFβ1 levels during radiotherapy were found to be useful in identifying patients at low risk for complications after radiation up to 86.4 Gy.4 Furthermore, a decrease in plasma TGFβ1 concentration to that of less than the pretreatment value during radiotherapy in patients without pulmonary complications supports the use of TGFβ1 as a predictive biomarker.22 However, De Jaeger et al20 did not find an association between increased levels of TGFβ1 and symptomatic RP, although the TGFβ1 level at the end of radiotherapy was significantly associated with the MLD and the preradiotherapy level.

Three recent studies demonstrated that the polymorphisms in the TGFβ1 gene strongly associated with normal tissue toxicity in patients with breast and gynecologic cancer after radiotherapy.26–28 For example, Quarmby et al28 found that the patients with −509TT or 869CC genotypes were between seven and 15 times more likely to develop severe fibrosis. Goitopoulos et al43 found that patients with homozygotes (TT) for the TGFβ1 509T allele had a 15-fold increase in fibrosis risk after radiotherapy compared with the CC homozygotes, and a strong linkage between the C-509T and Leu10Pro polymorphisms was reported.28,44,45 However, these results have been controversial. Andreassen et al26,46 first reported a possible association between selected SNPs and the risk of subcutaneous fibrosis in 41 Danish patients with breast cancer patients treated with postmastectomy radiotherapy and 26 patients with early-stage breast cancer after breast conservation treatment. However, a confirmatory study of 120 patients by the same group failed to demonstrate any association between the risk of radiation-induced subcutaneous fibrosis and SNPs in TGFβ1, x-ray repair cross-complementing gene (XRCC) 1, XRCC3, manganese superoxide dismutase gene-2, and ataxia telangiectasia mutated genes after postmastectomy radiotherapy.47 Understanding the combined effect of these genes on patient response to radiotherapy may shed some light on the predictive value of these genetic factors.

In our study, the distributions of TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C and rs1800469:C-509T genotypes in the patients of all ethnicities with lung cancer were similar to those reported in white patients in general.48 We used severe RP as the end point and found that only rs1982073:T869C was associated with a statistically significant reduced risk, although the other two SNPs were also associated with a nonsignificantly lower RP hazard. Because the patients in this analysis were treated consistently, it is unlikely that the differences in RP risk detected by TGFβ1 genotypes were due to such confounding factors. Of particular interest were the highly significant differences in RP risk according to the genotypes of rs1982073:T869C when patients were stratified according to MLD and V20. This observation implies that genetic factors may have played a greater role in influencing individual patient susceptibility when either relatively low doses were delivered or that a more limited volume of lung was exposed to high doses of radiation. This would seem to suggest that once the dose or volume is relatively large, the dosimetric factors would likely override inherent radiosensitivity as a result of the polymorphisms as investigated in this study. This has important implications for the role of genetic factors as we move increasingly to more conformal radiotherapy in which normal tissues receive lower doses and smaller volumes of tissues are exposed to higher doses than those from more conventional radiotherapy.

Our goal was to identify biomarkers that predict RP risk for patients with NSCLC before radiation starts. The results from this study demonstrated that TGFβ1 rs1982073:T869C was associated with a lower RP risk in patients with NSCLC treated with definitive radiotherapy, suggesting the possibility of using these biomarkers as predictive factors. We also need to understand the effect of these SNPs on disease outcomes. Furthermore, we need to validate our results, and we are planning to do so in a cohort of patients who received treatment more recently at our institution. Finally, although it was not the intent of this study, we need to investigate the CT/CC genotypes' mechanism in reducing RP risk and its interaction with other factors in the normal-tissue risk prediction models.

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Xianglin Yuan, Zhongxing Liao, James D. Cox, Luka Milas, Qingyi Wei

Financial support: Zhongxing Liao, Ritsuko Komaki, James D. Cox, Luka Milas, Qingyi Wei

Administrative support: Zhongxing Liao, Mary Martel, Ritsuko Komaki, James D. Cox, Qingyi Wei

Provision of study materials or patients: Zhongxing Liao, Susan L. Tucker, Li Mao, Xin Shelley Wang, Mary Martel, Ritsuko Komaki, James D. Cox, Qingyi Wei

Collection and assembly of data: Xianglin Yuan, Zhongxing Liao, Zhensheng Liu, Susan Tucker

Data analysis and interpretation: Xianglin Yuan, Zhongxing Liao, Li-E Wang, Susan L. Tucker, Luka Milas, Qingyi Wei

Manuscript writing: Xianglin Yuan, Zhongxing Liao, Luka Milas, Qingyi Wei, Susan Tucker

Final approval of manuscript: Xianglin Yuan, Zhongxing Liao, Susan L. Tucker, Mary Martel, Luka Milas, Qingyi Wei

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang S, Liao Z, Wei X, et al. Analysis of clinical and dosimetric factors associated with treatment-related pneumonitis (TRP) in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with concurrent chemotherapy and three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1399–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yom SS, Liao Z, Liu HH, et al. Initial evaluation of treatment-related pneumonitis in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham M, Purdy J, Emami B, et al. Clinical dose-volume histogram analysis for pneumonitis after 3D treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kong FM, Hayman JA, Griffith KA, et al. Final toxicity results of a radiation-dose escalation study in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Predictors for radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martel MK, Ten Haken RK, Hazuka MB, et al. Dose-volume histogram and 3-D treatment planning evaluation of patients with pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;28:575–581. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schallenkamp JM, Miller RC, Brinkmann DH, et al. Incidence of radiation pneumonitis after thoracic irradiation: Dose-volume correlates. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Bentzen SM, et al. Radiation dose prescription for non-small-cell lung cancer according to normal tissue dose constraints: An in silico clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Boersma L, et al. Individualized radical radiotherapy of non-small-cell lung cancer based on normal tissue dose constraints: A feasibility study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1394–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin H, Tucker S, Liu H, et al. Dose-volume thresholds and smoking status for the risk of treatment-related pneumonitis in inoperable non-small cell lung cancer treated with definitive radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.09.009. epub ahead of print on October 18, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker S, Liu H, Liao Z, et al. Analysis of radiation pneumonitis risk using a generalized lyman model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anscher MS, Kong FM, Andrews K, et al. Plasma transforming growth factor beta1 as a predictor of radiation pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anscher MS, Kong FM, Marks LB, et al. Changes in plasma transforming growth factor beta during radiotherapy and the risk of symptomatic radiation-induced pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabbani ZN, Anscher MS, Zhang X, et al. Soluble TGFbeta type II receptor gene therapy ameliorates acute radiation-induced pulmonary injury in rats. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao L, Sheldon K, Chen M, et al. The predictive role of plasma TGFbeta1 during radiation therapy for radiation-induced lung toxicity deserves further study in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massagué J. How cells read TGFbeta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li MO, Flavell RA. TGFbeta: A master of all T cell trades. Cell. 2008;134:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anscher MS, Garst J, Marks LB, et al. Assessing the ability of the antiangiogenic and anticytokine agent thalidomide to modulate radiation-induced lung injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barthelemy-Brichant N, Bosquee L, Cataldo D, et al. Increased IL-6 and TGFbeta1 concentrations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid associated with thoracic radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:758–767. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)01614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Jaeger K, Seppenwoolde Y, Kampinga HH, et al. Significance of plasma transforming growth factor-beta levels in radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1378–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Jaeger K, Seppenwoolde Y, Lebesque JV, et al. In response to Drs. Anscher and Kong. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novakova-Jiresova A, Van Gameren MM, Coppes RP, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta plasma dynamics and post-irradiation lung injury in lung cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans ES, Kocak Z, Zhou SM, et al. Does transforming growth factor-beta1 predict for radiation-induced pneumonitis in patients treated for lung cancer? Cytokine. 2006;35:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong F, Ao X, Wang L, et al. The use of blood biomarkers to predict radiation lung toxicity: A potential strategy to individualize thoracic radiation therapy. Cancer Control. 2008;15:140–150. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grainger DJ, Heathcote K, Chiano M, et al. Genetic control of the circulating concentration of transforming growth factor type beta1. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:93–97. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreassen CN, Alsner J, Overgaard J, et al. TGFB1 polymorphisms are associated with risk of late normal tissue complications in the breast after radiotherapy for early breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Ruyck K, Van Eijkeren M, Claes K, et al. TGFbeta1 polymorphisms and late clinical radiosensitivity in patients treated for gynecologic tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quarmby S, Fakhoury H, Levine E, et al. Association of transforming growth factor beta-1 single nucleotide polymorphisms with radiation-induced damage to normal tissues in breast cancer patients. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Program NS. National Institute of Environmental Health Science Genome Project, 2008. http://egp.gs.washington.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Letterio JJ, Roberts AB. Regulation of immune responses by TGFbeta. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Transforming growth factor-beta: Multiple actions and potential clinical applications. JAMA. 1989;262:938–941. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.7.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah R, Hurley CK, Posch PE. A molecular mechanism for the differential regulation of TGFbeta1 expression due to the common SNP-509C-T (c.−1347C>T) Hum Genet. 2006;120:461–469. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thys M, Schrauwen I, Vanderstraeten K, et al. The coding polymorphism T263I in TGFbeta1 is associated with otosclerosis in two independent populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2021–2030. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickson MR, Perry RT, Wiener H, et al. Association studies of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;139B:38–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JY, Park MH, Park H, et al. TNF-alpha and TGFbeta1 gene polymorphisms and renal allograft rejection in Koreans. Tissue Antigens. 2004;64:660–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Celedón JC, Lange C, Raby BA, et al. The transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGFB1) gene is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1649–1656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su ZG, Wen FQ, Feng YL, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 gene polymorphisms associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Chinese population. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:714–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saltzman BS, Yamamoto JF, Decker R, et al. Association of genetic variation in the transforming growth factor beta-1 gene with serum levels and risk of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1236–1244. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunning AM, Ellis PD, McBride S, et al. A transforming growth factor beta1 signal peptide variant increases secretion in vitro and is associated with increased incidence of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2610–2615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rube CE, Uthe D, Schmid KW, et al. Dose-dependent induction of transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) in the lung tissue of fibrosis-prone mice after thoracic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu X, Huang H, Bentel G, et al. Predicting the risk of symptomatic radiation-induced lung injury using both the physical and biologic parameters V(30) and transforming growth factor beta. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:899–908. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giotopoulos G, Symonds RP, Foweraker K, et al. The late radiotherapy normal tissue injury phenotypes of telangiectasia, fibrosis and atrophy in breast cancer patients have distinct genotype-dependent causes. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angèle S, Romestaing P, Moullan N, et al. ATMHaplotypes and cellular response to DNA damage: Association with breast cancer risk and clinical radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8717–8725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Severin DM, Leong T, Cassidy B, et al. Novel DNA sequence variants in the hHR21 DNA repair gene in radiosensitive cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreassen CN, Alsner J, Overgaard M, et al. Prediction of normal tissue radiosensitivity from polymorphisms in candidate genes. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andreassen CN, Alsner J, Overgaard M, et al. Risk of radiation-induced subcutaneous fibrosis in relation to single nucleotide polymorphisms in TGFB1, SOD2, XRCC1, XRCC3, APEX and ATM–a study based on DNA from formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue samples. Int J Radiat Biol. 2006;82:577–586. doi: 10.1080/09553000600876637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buraczynska M, Baranowicz-Gaszczyk I, Borowicz E, et al. TGFbeta1 and TSC-22 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. Nephron Physiol. 2007;106:69–75. doi: 10.1159/000104874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]