Abstract

Sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein (SLMAP) is a tail-anchored protein involved in fundamental cellular processes, such as myoblast fusion, cell cycle progression, and chromosomal inheritance. Further, SLMAP misexpression is associated with endothelial dysfunctions in diabetes and cancer. SLMAP is part of the conserved striatin-interacting phosphatase and kinase (STRIPAK) complex required for specific signaling pathways in yeasts, filamentous fungi, insects, and mammals. In filamentous fungi, STRIPAK was initially discovered in Sordaria macrospora, a model system for fungal differentiation. Here, we functionally characterize the STRIPAK subunit PRO45, a homolog of human SLMAP. We show that PRO45 is required for sexual propagation and cell-to-cell fusion and that its forkhead-associated (FHA) domain is essential for these processes. Protein-protein interaction studies revealed that PRO45 binds to STRIPAK subunits PRO11 and SmMOB3, which are also required for sexual propagation. Superresolution structured-illumination microscopy (SIM) further established that PRO45 localizes to the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria. SIM also showed that localization to the nuclear envelope requires STRIPAK subunits PRO11 and PRO22, whereas for mitochondria it does not. Taken together, our study provides important insights into fundamental roles of the fungal SLMAP homolog PRO45 and suggests STRIPAK-related and STRIPAK-unrelated functions.

INTRODUCTION

Membrane recruitment of protein complexes, cell signaling modules, and enzymes is a critical step for many cellular functions. The family of tail-anchored proteins is recognized for anchoring proteins and vesicles to specific membranes, such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the outer mitochondrial membrane (1), and tail-anchored proteins are characterized by a C-terminal single transmembrane domain, which is posttranslationally inserted into membranes (2, 3).

Sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein (SLMAP) is a tail-anchored protein first identified in myocardiac cells (4). In mammals, this protein is known to be involved in myoblast fusion during embryonic development, excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes, and cell cycle progression (5–8). Furthermore, SLMAP was identified to be a disease gene for Brugada syndrome, a cardiac channelopathy (9). The functional diversity of SLMAP is dependent on alternative splicing, leading to at least four different isoforms of the protein (4, 6, 7, 10). Importantly, gene expression analyses have implicated SLMAP misexpression with endothelial dysfunctions in diabetes, chromosomal aberrations, and cancer (11–14), and currently, SLMAP is the target of lectin-based treatment of drug-resistant cancer cells (15).

SLMAP is conserved from yeasts to humans, and characterized fungal SLMAP homologs include Neurospora crassa HAM-4 (hyphal anastomosis 4), Saccharomyces cerevisiae Far9p (factor arrest 9p) and Far10p, as well as Schizosaccharomyces pombe Csc1p (component of SIP complex 1p) (16–18). HAM-4 is essential for vegetative cell fusion, whereas Far9p and Far10p are required for pheromone-induced cell cycle arrest during yeast mating and Csc1p acts in cytokinesis. Interestingly, in a genome-wide screen for vacuolar protein sorting (vps)-deficient mutants, Far9p was also identified to be Vps64p and vacuolar morphology was altered in N. crassa ham-4 mutants, indicating a role for SLMAP homologs in organelle morphology in fungi (18, 19).

Recently, SLMAP has been identified to be an accessory protein to the human striatin-interacting phosphatase and kinase (STRIPAK) complex, a large multiprotein complex assembled around a core of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) subunits (20). In addition to PP2A structural (PP2AA) and catalytic (PP2Ac) subunits, human STRIPAK complex contains striatins (regulatory PP2AB‴ subunits), striatin-interacting proteins 1 and 2 (STRIP1/2), monopolar spindle-one-binder (MOB) proteins, germinal center kinase III (GCKIII) protein kinases, and cerebral cavernous malformation protein3 (CCM3). This core STRIPAK complex is able to assemble in a mutually exclusive way with other accessory proteins, like SLMAP and the suppressor of IκB kinaseε (SIKE) or a cortactin-binding protein 2 family member (CTTNBP2 or CTTNBP2NL) (21). The high diversity of STRIPAK and STRIPAK-like complexes makes estimation of the molecular weight of the complex difficult. Human STRIPAK was found to play a role in Golgi apparatus polarization and is involved in mitosis by tethering Golgi vesicles to centrosomes and the nuclear membrane in a cell cycle-specific manner (22, 23).

STRIPAK-equivalent complexes have been found in a number of diverse organisms from yeasts to humans. The Drosophila melanogaster dSTRIPAK (Drosophila STRIPAK) complex is a negative regulator of the Hippo signaling pathway (24). The S. cerevisiae Far complex plays a role in cell cycle arrest during mating as well as acts in an antagonistic fashion toward TORC2 (target of rapamycin complex 2) signaling (17, 25). The S. pombe SIP (SIN [septation initiation network] inhibitory PP2A) complex is required for the coordination of mitosis and cytokinesis by inhibiting SIN (16). The N. crassa STRIPAK complex controls nuclear accumulation of the MAK1 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and regulates chemotropic interactions between conidial germlings (26). Moreover, in the fungal model organism Sordaria macrospora (27–29), the STRIPAK complex is required for cell fusion and sexual reproduction, namely, the formation of multicellular fruiting bodies (30). Discrete STRIPAK components have been characterized in other filamentous fungi, e.g., Aspergillus nidulans, Fusarium graminearum, Magnaporthe oryzae, and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (31–34); however, a description of the STRIPAK complex in these fungi is still lacking.

S. macrospora STRIPAK consists of PP2AA, PP2Ac1, striatin homolog PRO11, STRIP homolog PRO22, and the MOB protein SmMOB3. Strikingly, a mutant lacking the striatin homolog PRO11 can be complemented by mouse striatin cDNA (35), thereby highlighting the suitability of S. macrospora for studying the molecular function of STRIPAK components. Finally, defects in multicellular differentiation can easily be observed in S. macrospora, since the fungus forms complex three-dimensional fruiting bodies (perithecia) within 7 days without the need of a mating partner, and early developmental structures (coiled hyphae termed ascogonia and spherical immature fruiting bodies termed protoperithecia) are not masked by any asexual spores (27).

The aim of this study was to functionally characterize PRO45, the SLMAP homolog from S. macrospora, and provide insights into its role within the fungal STRIPAK complex. Protein-protein interaction studies indeed showed that PRO45 is part of fungal STRIPAK. We further established superresolution structured-illumination microscopy (SIM) for S. macrospora to distinctly demonstrate that PRO45 cellular localization is dependent on STRIPAK integrity. Here, we provide evidence that the SLMAP homolog PRO45 plays a fundamental role in fungal development and might have STRIPAK-related and STRIPAK-unrelated functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

All S. macrospora strains used in this study (Table 1) were grown under standard conditions and transformed with recombinant plasmids as described previously (36, 37), with the following modifications. Fernbach flasks containing liquid complex medium (CM) were inoculated with S. macrospora strains and incubated for 3 days. The cell wall was degraded using 0.05 g/ml VinoTaste Pro enzyme (Novozymes, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), 0.015 g/ml caylase (Cayla, Toulouse, France), and 27 U of chitinase (ASA Spezialenzyme GmbH, Wolfenbüttel, Germany). Transformation was performed using 15 to 20 μg of circular (ectopic integration) or linearized (homologous integration) plasmid DNA.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype and phenotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| S91327 | Wild type, fertile | Culture collectionb |

| S84595 | Spore color mutant fus (fus1-1), fertile | Culture collectionb |

| S96888 | Δku70, recipient strain for homologous recombination | 45 |

| N161 | Single-spore isolate, sterile, Δpro45::Hphr | This study |

| R7329 | Single-spore isolate, sterile, Δpro45::Hphr fus | This study |

| N401 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of p45-CTAP into N161, fertile, Δpro45 gpd(p)::pro45::ctap::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| N506, N508 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of pEGFP-45 into N161, fertile, Δpro45 gpd(p)::egfp::pro45::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| N861 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of pEGFP-45 and pDsREDKDEL into N161, fertile, Δpro45 gpd(p)::egfp::pro45::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat gpd(p)::Spro41::DsRED::KDEL::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| N883 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of pEGFP-45 and pRH2B into N161, fertile, Δpro45 gpd(p)::egfp::pro45::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat gpd(p)::hh2b::tdTomato::trpC(t) trpC(p)::hph | This study |

| N1032 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of p45ΔFHA-TAP into N161, sterile, Δpro45 gpd(p)::pro45ΔFHA::ctap::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| N1111 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of p45ΔTM-EGFP into N161, fertile, Δpro45 gpd(p)::pro45ΔTM::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| S5.7 | Single-spore isolate, sterile, Δpro11::Hphr | 30 |

| S56 | Single-spore isolate, sterile, Δpro22::Hphr | 30 |

| S106172 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of pDS23 into S91327, fertile, gpd(p)::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| S123155 | Single-spore isolate, ectopic integration of pEGFP-45 into S56, sterile, Δpro22 gpd(p)::egfp::pro45::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| T104.4 | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of p45-EGFP and pHA11 into S91327, fertile, gpd(p)::pro45::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat ccg1(p)::HA::pro11 trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| T105.2 | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of p45-EGFP and pFLAGMob3 into S91327, fertile, gpd(p)::pro45::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat ccg1(p)::3×FLAG::Smmob3 trpC(p)::hph | This study |

| T1201-A | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of pHA11 into S91327, fertile, ccg1(p)::ha::pro11 trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| T1202-A2 | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of pFLAGMob3 into S91327, fertile, ccg1(p)::3×FLAG::Smmob3 trpC(p)::hph | This study |

| T131-D5 | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of p45-EGFP into S91327, fertile, gpd(p)::pro45::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| T133-E6 | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of p45-EGFP and pHA11 into S91327, fertile, gpd(p)::pro45::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat ccg1(p)::ha::pro11 trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| T135-B2 | Primary transformant, ectopic integration of pEGFP-45 into S5.7, sterile, Δpro11 gpd(p)::egfp::pro45::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

hph, hygromycin resistance gene; nat, nourseothricin resistance gene.

Culture collection, Lehrstuhl für Allgemeine und Molekulare Botanik, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

Cloning was performed in S. cerevisiae strain PJ69-4A using the homologous recombination system described previously (38, 39). Yeast cells were transformed by electroporation according to the method of Becker and Lundblad (40) in a Multiporator electroporation system (Eppendorf, Wesseling-Berzdorf, Germany) at 1.5 kV. Transformants were selected by screening for uracil prototrophy. For DNA isolation, yeast cell walls were broken with glass beads (0.5 mm diameter), followed by DNA extraction with an E.Z.N.A. plasmid miniprep kit I (Peqlab Biotechnologie GmbH, Erlangen, Germany).

For documentation of vegetative growth rates, S. macrospora strains were grown on corn meal-malt fructification medium (BMM) for 2 days, and standard inocula were transferred to synthetic Westergaard's (SWG) medium (41), where the growth distance was determined for 2 consecutive days. Perithecium formation was determined after 7 days of growth on BMM using 10 regions of 37 mm2 from 2 plates per strain.

Construction of plasmids.

All plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. pDS16 was generated by insertion of an hph cassette (1.4-kb EcoRI fragment of pDrivehph) (42) between a 5′ and 3′ region of S. macrospora SMAC_01224 in pRS426 (43). Flanking regions were amplified using primers SMACG_01224_5F-fw/SMACG_01224_5F-rv (5′) and SMACG_01224_3F-fw/SMACG_01224_3F-rv (3′).

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| p45-CTAP | pro45 cDNA fused to a C-terminal TAP tag in pDS22, gpd(p)::pro45::ctap::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| p45-EGFP | pro45 cDNA in pDS23 gpd(p)::pro45::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| p45ΔFHA-TAP | pro45 cDNA (deletion of bp 682–855) fused to a C-terminal TAP tag in pDS22, gpd(p)::pro45ΔFHA::ctap::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| p45ΔTM-EGFP | pro45 cDNA (deletion of bp 2302–2370) in pDS23, gpd(p)::pro45ΔTM::egfp::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| pDrivehph | Hygromycin resistance cassette consisting of the hph gene from Escherichia coli and the trpC promoter from Aspergillus nidulans in pDrive | 42 |

| pDS16 | hph gene with 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of SMAC_01224 (pro45) in pRS426 pro45_5′::trpC(p)::hph::pro45_3′ trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| pDS22 | C-terminal TAP tag in pRSnat, gpd(p)::ctap::trpC(t) trpc(p)::nat | Nowrousian, unpublished |

| pDS23 | egfp in pRSnat, gpd(p)::egfp::trpC(t) trpc(p)::nat | 44 |

| pDsREDKDEL | DsRed fused with the N-terminal signal sequence for cotranslational insertion into the ER from pro41 and the C-terminal ER retention signal KDEL, gpd(p)::Spro41::DsRED::KDEL::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | 41 |

| pEGFP-45 | pro45 cDNA in pDS23, gpd(p)::egfp::pro45::trpC(t) trpC(p)::nat | This study |

| pFLAGMob3 | Smmob3 cDNA fused to an N-terminal 3× FLAG tag in pRShyg, ccg1(p)::3×FLAG::Smmob3 trpC(p) Hphr | 30 |

| pHA11 | pro11 cDNA fused to an N-terminal HA tag in pRSnat, ccg1(p)::HA::pro11 trpC(p)::nat | 30 |

| pRH2B | Histone H2B fused to TdTomato, gpd(p)::hh2b::tdTomato::trpC(t) trpC(p)::hph | I. Teichert and U. Kück, unpublished data |

| pRS426 | URA3 Hphr | 43 |

| pRSnat | pRS426 derivative, URA3 Natr | 77 |

Hphr, hygromycin resistant; Natr, nourseothricin resistant.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′– 3′) |

|---|---|

| 45_start-fw | ATGACGGCTGTCGCGAATC |

| 1224KOvp1neu | GAGGTAAGAGCAAGCTTGTC |

| 1224KOvp2neu | GTACCAATGGCAAGATACGC |

| 1224KOvp3 | GACGACGACGAATTGGATCG |

| 1757 | AGCTGACATCGACACCAACG |

| 45_CTAP-bw | AAATTCTTTTTCCATCTTCTCTTTTCGTTCTTCGCCTGCGGCTGCCACCC |

| 45_CTAP-fw | CTTCATCGCAGCTTGACTAACAGCTACATGACGGCTGTCGCGAATCCC |

| 45_CtermGFP-bw | CAGCTCCTCGCCCTTGCTCACCATGTTCTTCGCCTGCGGCTGCCACCC |

| 45_int-bw | GCTTGGCATTTCGCATTTCC |

| 45_int-bw-2 | GGTCGCTCGGTGATTCCTC |

| 45_int-fw | CCCTGTCACGACTGAACATATTG |

| 45_int-fw-2 | CGCCAGAAAATCGCGAGTC |

| 45_int-fw-3 | CAGCCGCAGGCGAAGAAC |

| 45_NtermGFP-fw | CTCTCGGCATGGACGAGCTGTACAAGATGACGGCTGTCGCGAATCCCC |

| 45ΔFHA_CTAP-bw | CGTGGGGTTCCGACTCGCGATTTTCTGGCGAAATGTCGGGGTAAAAGG |

| 45ΔTM_CEGFP-bw | CTCACCATGTTCTTCGCCTGCGGCTGGGCCTGTATCAACGCACGATCCTG |

| 45ΔTM_NEGFP-bw | GTTAAGTGGATCTAGTTCTTCGCCTGCGGCTGGGCCTGTATCAACGCACGATC |

| hph1MN | CGATGGCTGTGTAGAAGTACTCGC |

| hph2_2010-bw | GCCTCCAGAAGAAGATGTTG |

| hph2MN | ATCCGCCTGGACGACTAAACCAA |

| SMACG_01224_3F-rv | GCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGCCCGTAACTTTCCATACGTAAATACC |

| SMACG_01224_3F-fw | GCCCAAAAATGCTCCTTCAATATCAGTTGCCAGTCTCTGTCTTTCTCATACCACA |

| SMACG_01224_5F-rv | CGAGGGCAAAGGAATAGGGTTCCGTTGAGGGTTCTCTTGAGATTGTTCCTTTGC |

| SMACG_01224_5F-fw | GTAACGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACGATCCAGATCTTCCATCTCAACAAG |

For the construction of tandem affinity purification (TAP) vectors, fragments were amplified by primers 45_CTAP-fw and 45_int-bw and primers 45_int-fw and 45_CTAP-bw and transformed into yeast with BglII-linearized pDS22 (M. Nowrousian, unpublished data). For the construction of p45ΔFHA-TAP, the amplicons obtained with primers 45_int-fw/45ΔFHA_CTAP-bw and 45_int-fw-2/45_int-bw-2 were transformed into ClaI-linearized p45-CTAP.

For construction of green fluorescent protein (GFP) vectors, PCR fragments were amplified with primers 45_NtermGFP-fw/45_int-bw and 45_int-fw/45_CtermGFP-bw and cotransformed into yeast with either SpeI-linearized (N-terminal fusion) or BglII-linearized (C-terminal fusion) pDS23 (44), resulting in plasmids pEGFP-45 and p45-EGFP, respectively. For the construction of a truncated version of PRO45 lacking the C-terminal transmembrane domain, the amplicons obtained with primers 45_int-fw/45ΔTM_CEGFP-bw and 45_int-fw-3/1757 were transformed into yeast together with NotI-hydrolyzed pEGFP-45, resulting in plasmid p45ΔTM-EGFP.

Generation of a pro45 deletion strain.

To generate pro45 deletion (Δpro45) strains by homologous recombination, the 4.9-kb pro45 deletion cassette of pDS16 was transformed into S. macrospora Δku70 strain S96888 (45). Ascospore isolates, in which the pro45 open reading frame was replaced by the hph cassette and which had the wild-type (N161) or the fus (R7329) genetic background, were obtained as described previously by crosses to the fus spore color mutant (45). Strains were analyzed by PCR using primer pairs 1224KOvp1neu/hph1MN, 1224KOvp2neu/hph2MN, and 1224KOvp1neu/1224KOvp3 for the validation of the 5′flanking region, the 3′ flanking region, and the wild-type control, respectively. Southern blotting and hybridization were performed according to standard techniques (46). A 1,012-bp (bp 891 to 1903) pro45 fragment was generated by the digestion of p45-CTAP with SacI, labeled with 32P, and used as the DNA probe to detect pro45, whereas a 616-bp hph fragment was generated by PCR using the primer pair hph1MN/hph2_2010-bw and used to detect the hph cassette.

Light and fluorescence microscopy.

Light and fluorescence microscopic investigations were carried out with an AxioImager.M1 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using an XBO 75 xenon lamp (LEJ, Jena, Germany) for fluorescence excitation. For detection of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and detection of DsRED and MitoTracker orange CMTMRos fluorescence, Chroma filter sets (Chroma Technology Corp., Bellows Falls, VT, USA) 49002 (excitation filter HQ470/40, emission filter HQ525/50, beam splitter T495LPXR) and 49008 (excitation filter HQ560/40, emission filter ET630/75m, beam splitter T585lp), respectively, were used. For detection of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX, Chroma filter set 31000v2 (excitation filter D350/50, emission filter D460/50, beam splitter 400dclp) was used. Images were captured with a Photometrix Cool SnapHQ camera (Roper Scientific, Martinsried, Germany) and analyzed with MetaMorph software (version 7.7.0.0; Universal Imaging, Bedford Hills, NY, USA).

To analyze hyphal fusion, strains were inoculated on minimal medium containing soluble starch (MMS) on top of a layer of cellophane (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). After incubation for 2 days, hyphal fusion was analyzed by light microscopy (47). Furthermore, microscopy was used to determine sexual development and the fluorescence of selected strains on BMM-covered slides (48).

To determine differences in sexual development, strains were grown for 2, 4, and 7 days, and at each time point, the most advanced stages were detected. For fluorescence microscopy, strains were grown for 2 days on BMM-covered slides. For visualization of nuclei, mitochondria, and the ER, hyphae were stained with 50 μg/ml DAPI (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), 100 μM MitoTracker orange CMTMRos (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), and 100 μM ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), respectively.

Formation of perithecia was documented using a stereomicroscope (Stemi 2000-C; Zeiss) equipped with a digital camera (AxioCamERc 5s; Zeiss). Recorded images were processed with MetaMorph, Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe Illustrator CS4 software.

Superresolution SIM.

Strains were grown for 2 days on BMM-covered slides, and fixation was performed with a 0.2% formaldehyde solution for 5 min, followed by a washing step with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Staining was performed as described above.

Structured-illumination microscopy (SIM) images were taken with an ELYRA S.1 microscope (63× [numerical aperture, 1.4] oil-immersion objective; CellObserver SD; Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with the software ZEN 2010 D (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). For image acquisition, 5 grid rotations were used with average values for 2 being used. Beam splitter settings were as follows: for GFP (488), bandpass (BP) 495 nm to 550 nm and longpass (LP) 750 nm; for DsRED and MitoTracker orange CMTMRos (568), BP 570 nm to 620 nm and LP 750 nm; for DAPI and ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX (405), BP 420 nm to 480 nm and LP 750 nm. For SIM calculations with fluorescent hyphae, the following manual settings were used: noise filter, −3; super resolution frequency weighting, 1.0; and for sectioning, zero order, 100/first order, 75/second order, 75. Recorded images were processed with ZEN 2010 D, Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe Illustrator CS4 software.

Tandem affinity purification and MS.

Tandem affinity purification of PRO45-TAP and PRO45ΔFHA-TAP, tryptic digestion of proteins, and multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) (49, 50) analysis were performed as described previously (30) using an Orbitrap Velos ion trap mass spectrometer coupled to an Accela quaternary ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Proteome Discoverer (version 1.2) software was used for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data interpretation, and data were searched against those in the S. macrospora database (smacrosporapep_v4_110909) with tryptic peptides, a mass accuracy of 10 ppm, a fragment ion tolerance of 0.8 Da, and oxidation of methionine as a variable modification, with 4 missed cleavage sites being allowed. All accepted results had a high peptide confidence with a score of 10.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Plasmid p45-EGFP was cotransformed with pFLAGMob3 and pHA11 (30) into the S. macrospora wild-type strain S91327, resulting in hygromycin- and nourseothricin-resistant strains T105.2, T104.4, and T133-E6 (Table 1). Additionally, pDS23 (44) was cotransformed with pHA11 and pFLAGMob3 to generate T1201-A and T1202-A2, respectively, which served as control strains.

Purification of FLAG- and GFP-tagged proteins was performed using an anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and GFP-Trap GFP-binding protein (Chromotek, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany), whereas hemagglutinin (HA) purification was performed using an anti-HA antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), which was subsequently recovered by protein A-Sepharose (Amersham GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Crude protein extracts and immunopurified complexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and immunodetection with anti-FLAG (anti-FLAG M2; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), anti-GFP (Living Colors JL-8; TaKaRa Bio Europe/Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France), and anti-HA (monoclonal anti-HA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) antibodies in combination with an anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Cell Signaling). Signal detection was performed using an Immun-Star WesternC (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) or SuperSignal West Femto (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) chemiluminescent solution on a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany).

RESULTS

A pro45 deletion strain is sterile and shows a defect in hyphal fusion.

Recently, a homolog of the human STRIPAK complex was identified in S. macrospora (30). This fungal complex consists of the striatin homolog PRO11, the STRIP1/2 homolog PRO22, SmMOB3, and PP2A subunits. STRIPAK complexes from different systems contain further accessory components; among them is SLMAP, which interacts with distinct STRIPAK subunits and links STRIPAK subcomplexes to the nuclear envelope (22, 51).

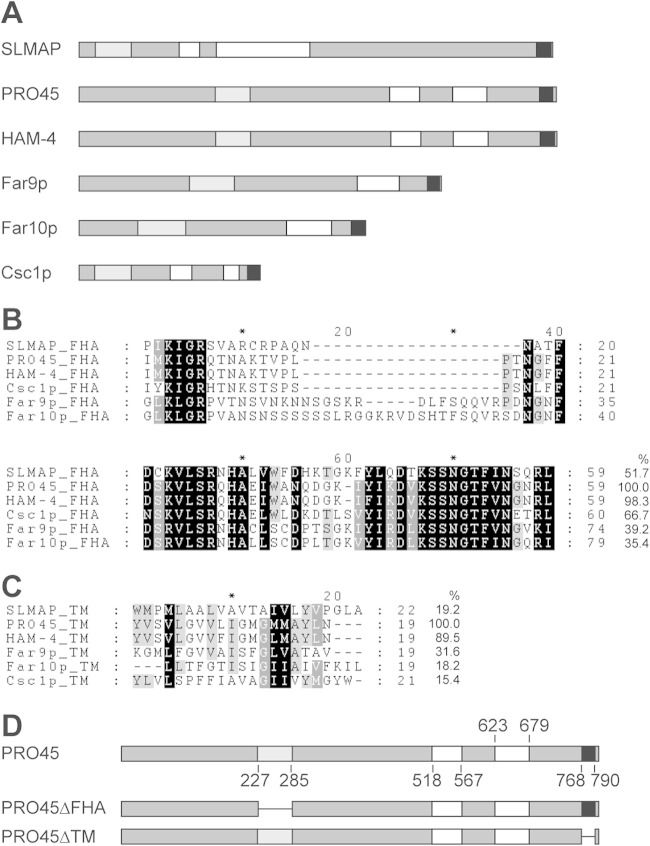

We used BLAST (52) to search for an S. macrospora homolog of SLMAP (gi⃓109731644) and identified SMAC_01224, which we termed PRO45 due to the phenotype of the mutant, as described below. Reciprocal BLAST analysis confirmed that PRO45 is an ortholog of SLMAP. Further, PRO45 shows the same domain organization as SLMAP and other fungal SLMAP homologs, such as N. crassa HAM-4 and S. cerevisiae Far9p/Far10p, with a forkhead-associated (FHA) domain, two coiled-coil domains, and a C-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain typical for tail-anchored proteins (Fig. 1A). The FHA domain is a phosphoprotein-binding domain that specifically recognizes phosphothreonine residues, whereas coiled-coil domains contain α helices that are wound around each other and that mediate protein-protein interactions (53, 54). PRO45 consists of 796 amino acids and shows 10.9% and 92.5% overall amino acid sequence identity to human SLMAP and N. crassa HAM-4, respectively. The amino acid sequence identity between S. macrospora and human SLMAP is increased within conserved domains, as shown by the amino acid sequence alignments of the FHA and TM domains (Fig. 1B and C). Here, the amino acid sequence identity was 51.7% and 19.2% for the FHA and the TM domains, respectively.

FIG 1.

SLMAP homologs. (A) Domain structure of SLMAP and fungal homologs. Proteins are depicted as medium gray bars. Light gray, white, and black bars, FHA, coiled-coil, and TM domains, respectively. Domains were analyzed by the use of the ELM (75) and TMPred (76) programs. (B, C) Amino acid alignment of FHA (B) and TM domains (C) from the indicated SLMAP homologs. Amino acid sequence identities (in percent) are given at the end of the alignments in relation to the S. macrospora PRO45 amino acid sequence. SLMAP, human SLMAP (GenBank accession number AAI14628.1); PRO45, S. macrospora PRO45 (GenBank accession number CCC07657.1); HAM-4, N. crassa HAM-4 (GenBank accession number EAA34844.2); Csc1p, S. pombe Csc1p (GenBank accession number NP_595762.1); Far9p, S. cerevisiae Far9p (GenBank accession number NP_010486.3), Far10p, S. cerevisiae Far10p (GenBank accession number EGA73760.1). (D) Domain structure of S. macrospora PRO45 derivatives PRO45ΔFHA and PRO45ΔTM. Numbers give the amino acid positions of the domains depicted in panel A.

To functionally characterize PRO45, we generated a pro45 deletion strain by homologous recombination of a pro45 deletion cassette using a nonhomologous end-joining-deficient Δku70 strain as a host (45). Ascospore isolates that carried the hph marker cassette instead of pro45 and that were devoid of the ku70 background were obtained from crosses of primary transformants to a fus spore color mutant (55). Two randomly selected ascospore isolates, N161 (Δpro45) and R7329 (Δpro45/fus), were subjected to Southern analysis, confirming the deletion of the pro45 gene (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Vegetative growth was strongly reduced in the mutant compared to that in the wild type, and this defect was restored by transformation with the full-length gene (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material).

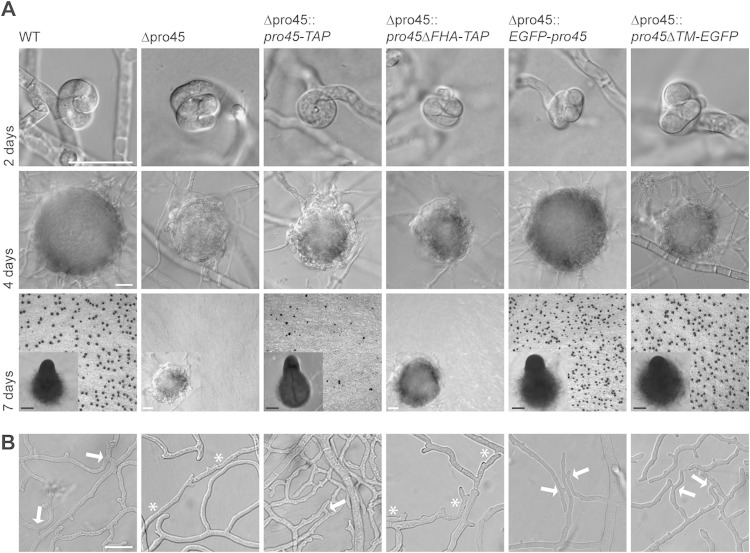

All Sordaria STRIPAK components characterized so far are involved in sexual development, i.e., the formation of sexual fruiting bodies (perithecia) (35, 56, 57). We therefore analyzed the pro45 deletion strain for defects in the sexual cycle. Sexual development starts with the formation of a hyphal coil (ascogonium) 2 days after inoculation. At day 4, enveloping hyphae have covered the ascogonium, thereby forming melanized spherical structures (protoperithecia) that develop further into mature, pear-shaped perithecia. As can be seen from Fig. 2A, the wild type forms ascogonia, protoperithecia, and mature perithecia within the expected time frame on BMM fructification medium. In contrast, the Δpro45 mutant forms only protoperithecia that do not develop any further. To verify that the observed defect is due to deletion of the pro45 gene, we ectopically integrated wild-type pro45 gene copies into the Δpro45 mutant. Since whole transcriptome shotgun sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis showed that pro45 transcript levels were very low (58), we expressed pro45 from the Aspergillus nidulans gpd promoter (59). Two different translational fusions of PRO45 with a tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag (pro45-TAP) and a GFP tag (EGFP-pro45) were able to complement the sexual developmental defect of the Δpro45 mutant (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). The observed sexual phenotype for S. macrospora Δpro45 is the most severe developmental phenotype described so far for a fungal SLMAP mutant and clearly differs from the phenotype of an N. crassa ham-4 mutant that is still able to complete the sexual cycle (18).

FIG 2.

Microscopic investigation of sexual development and hyphal fusion in the wild type (WT) as well as in the Δpro45 mutant and different transformants. (A) Strains were grown for 7 days on BMM-covered glass slides (48), and sexual structures were analyzed after 2, 4, and 7 days to document the development of ascogonia, protoperithecia, and mature perithecia, respectively. When possible, macroscopic images of mature perithecia growing on solid BMM plates were taken (7 days, insets). Bars, 20 μm (white) and 100 μm (black). (B) Subperipheral regions 5 to 10 mm from the colony edges were investigated for hyphal fusion. Arrows, hyphal fusion events; asterisks, hyphal contacts without fusion. Bar, 20 μm.

Many mutants impaired in sexual development are also impaired in vegetative hyphal fusion and vice versa, although this correlation is not strict (e.g., see references 27 and 60 to 62). Mutants lacking Sordaria STRIPAK components PRO11, PRO22, and SmMOB3 are also impaired in vegetative hyphal fusion (30, 56). We thus assessed hyphal fusion in the Δpro45 mutant and complemented strains. Like the other STRIPAK mutants, the Δpro45 mutant is unable to undergo hyphal fusion, although hyphae frequently grow side by side (Fig. 2B, asterisks). In contrast, wild-type and Δpro45 strains harboring an ectopically integrated pro45-TAP or EGFP-pro45 gene are able to undergo hyphal fusion, which is indicated by fusion bridges between hyphae (Fig. 2B, arrows). The aforementioned phenotypes for the Δpro45 mutant, namely, a defect in sexual development and hyphal fusion, have also been described for the S. macrospora Δpro11, Δpro22 (30), and ΔSmmob3 STRIPAK mutants (56) and point to a role for PRO45 in the fungal STRIPAK complex.

As mentioned earlier, in silico analysis identified an FHA domain, two coiled-coil domains, and a C-terminal TM domain in PRO45. To functionally analyze these domains, we generated mutated PRO45 versions lacking either the C-terminal TM domain (PRO45ΔTM-EGFP) or the N-terminal FHA domain (PRO45ΔFHA-TAP; Fig. 1D) and expressed them in the Δpro45 mutant as a host strain. Strains carrying the PRO45ΔTM-EGFP version were indistinguishable from the wild type with respect to fruiting body formation and hyphal fusion (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). In contrast, PRO45ΔFHA-TAP was unable to restore sexual development and hyphal fusion in the pro45 deletion strain, while a TAP-tagged full-length PRO45 fusion was able to (Fig. 2). Thus, the FHA domain plays a fundamental role in overall PRO45 function, whereas the TM domain is dispensable for hyphal fusion and sexual development.

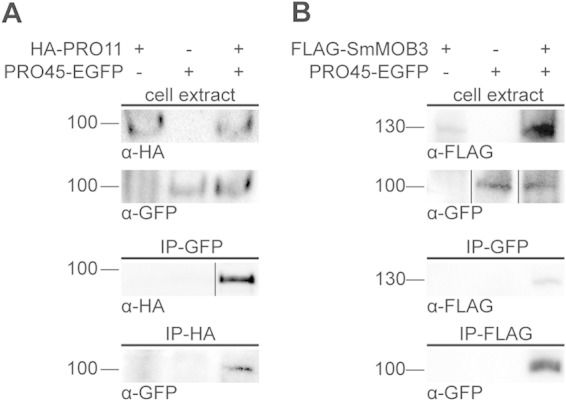

PRO45 interacts with STRIPAK components PRO11 and SmMOB3.

Our incentive to study the PRO45 protein was to establish it as an additional component of the S. macrospora STRIPAK complex. Therefore, we performed TAP followed by MS with a strain carrying a PRO45-TAP protein in the Δpro45 mutant background. This strain is able to form perithecia and to undergo hyphal fusion, proving the functionality of the TAP fusion construct (Fig. 2).

TAP-MS was carried out three times, and all detected proteins are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All three TAP-MS analyses with PRO45 as the bait yielded large amounts of the bait protein (234 spectral counts), as well as peptides from previously identified S. macrospora STRIPAK components PRO11 (164 spectral counts) and SmMOB3 (22 spectral counts) (Table 4). The S. macrospora STRIPAK complex contains further subunits, PRO22, PP2AA, and PP2Ac (30). However, these STRIPAK subunits were not detected in our TAP-MS experiments. We performed coimmunoprecipitation to confirm the interactions between PRO45 and PRO11 as well as SmMOB3 (Fig. 3). For this experiment, we used S. macrospora strains carrying GFP-tagged PRO45 and either HA-tagged PRO11 or FLAG-tagged SmMOB3, as well as control strains carrying only one tagged protein. Using these tagged versions, we verified the interaction of PRO45 with PRO11 (Fig. 3A) and PRO45 with SmMOB3 (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 4.

STRIPAK components detected by TAP-MS with PRO45 derivatives as the bait

| S. macrospora locus tag | Spectral count (peptide count) |

STRIPAK componenta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRO45 MS1 | PRO45 MS2 | PRO45 MS3 | Sum for PRO45 MS1 to MS3 | PRO45ΔFHA | ||

| SMAC_00877 | 3 (3) | 16 (4) | 3 (3) | 22 | 8 (4) | SmMOB3/MOB-3/MOB3 |

| SMAC_01224 | 18 (4) | 206 (17) | 10 (7) | 234 | 48 (20) | PRO45/HAM-4/SLMAP |

| SMAC_08794 | 23 (9) | 134 (19) | 7 (7) | 164 | 42 (16) | PRO11/HAM-3/striatin |

The designations for S. macrospora/N. crassa/human proteins are presented.

FIG 3.

PRO45 interacts with PRO11 and SmMOB3. Strains carrying GFP-tagged PRO45, HA-tagged PRO11, or FLAG-tagged MOB3, as indicated, were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-HA, anti-FLAG, and anti-GFP antibodies. Subsequent Western analysis detected epitope-tagged proteins. (A) Interaction of PRO45 and PRO11. For immunoprecipitation with GFP (IP-GFP), data from two different experiments are shown. (B) Interaction of PRO45 and SmMOB3. GFP was detected in cell extracts in two different experiments with different chemiluminescence solutions. Numbers to the left of the blots are molecular masses (in kilodaltons).

We further assessed whether the FHA domain, which is crucial for PRO45 function, mediates protein-protein interaction within STRIPAK. Therefore, TAP-MS was performed with sterile strain N1032 carrying a PRO45ΔFHA-TAP fusion protein in the Δpro45 mutant background (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). TAP-MS established that both PRO11 and SmMOB3 were still detectable with reasonable spectral counts (Table 4). This result suggests that the FHA domain, which is supposed to mediate phosphoprotein interactions, is dispensable for the interaction of PRO45 with PRO11 and SmMOB3.

PRO45 localizes to the nuclear envelope, ER, and mitochondria.

SLMAP has been described to be targeted to different membrane systems, including the sarcolemma, the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and the endoplasmic reticulum, as well as the outer mitochondrial membrane (4, 7, 22, 63). To assess the localization of PRO45 in S. macrospora, we generated a translational fusion of PRO45 to an N-terminal GFP tag and showed its functionality by complementation of the Δpro45 mutant phenotype (Fig. 2). Initial microscopic analysis with EGFP-PRO45 suggested that the protein localizes to a membrane. To scrutinize PRO45 localization at a higher resolution beyond the Abbe diffraction limit, we employed superresolution SIM. We chose SIM since it allows doubling of the resolution of a conventional wide-field (WF) fluorescence image by a combination of spatially structured illumination and computational three-dimensional reconstruction, using conventional fluorophores and dyes (64).

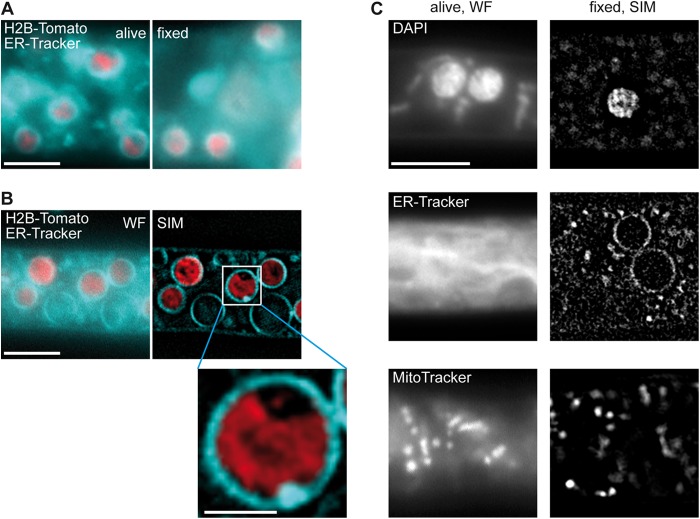

Due to the longer acquisition times required when using SIM in comparison to those required when using conventional fluorescence microscopy, we had to fix fungal samples. To confirm that our microscopic studies did not provide artificial localization data, we first tested the effect of fixation and SIM computational reconstruction. For this purpose, we used N883, a strain carrying histone H2B labeled with tdTomato, and stained ER membranes with ER-Tracker. After fixation, no artifacts were observed at the membrane and nuclear signals in WF images (Fig. 4A). By comparison of WF and reconstructed (SIM) images, it appeared that computational reconstruction did not lead to artifacts in localization but led to a highly refined membrane structure (Fig. 4B). We further tested organelle markers for usage in SIM (Fig. 4C). Nucleus, ER, and mitochondrial labeling with DAPI, ER-Tracker, and MitoTracker, respectively, revealed that SIM is a highly suitable superresolution microscopy method for filamentous fungi.

FIG 4.

Establishment of superresolution SIM for S. macrospora. (A) Hyphae of S. macrospora N883 carrying a tdTomato-tagged histone 2B (H2B) were stained with ER-Tracker. Unfixed cells (left) were compared to cells fixed with 0.2% formaldehyde (right). Bar, 5 μm. (B) To determine the effect of Fourier transformation, strain N883 was stained with ER-Tracker and micrographs were taken before (WF) and after (SIM) computational reconstruction. Bars, 5 μm and 1 μm (inset). (C) Dyes for different organelles were tested for use in SIM. Bar, 5 μm.

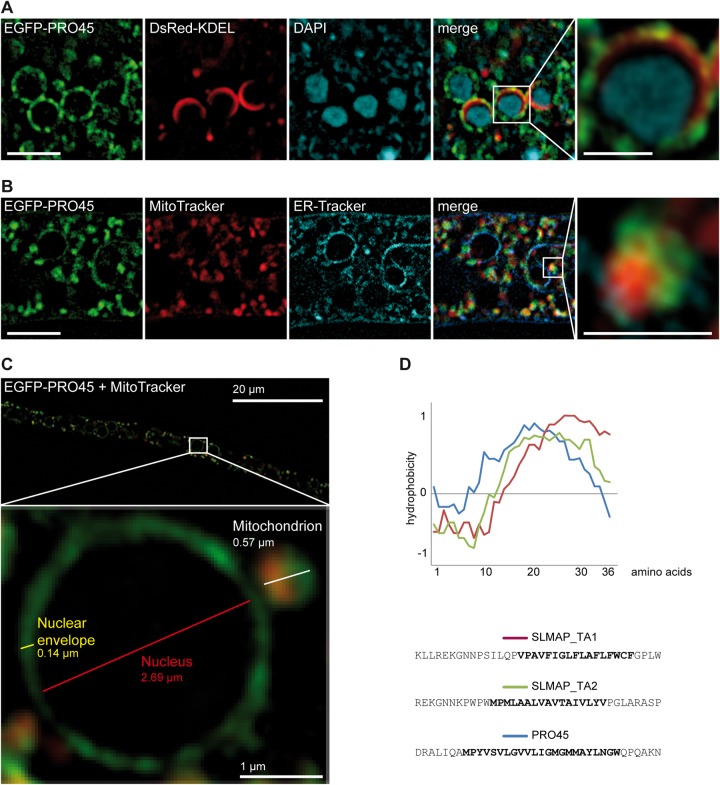

The SIM images demonstrated that PRO45 localizes to ring-like structures and to patches. Colocalization of EGFP-PRO45 with ER-targeted DsRed (DsRed-KDEL) (41) and simultaneous DAPI staining revealed an association of PRO45 with the ER, mainly to patches at the nuclear envelope (Fig. 5A). This is consistent with previously published data from N. crassa (26). However, some of the PRO45 patches did not colocalize with the ER marker DsRed-KDEL. Colocalization of EGFP-PRO45 with MitoTracker showed that non-ER fluorescent patches were closely associated with mitochondria (Fig. 5B). To assess the association of PRO45 with mitochondria and a possible connection between PRO45-containing ER and mitochondrial structures more closely, we analyzed strain N506 carrying EGFP-PRO45 labeled with MitoTracker. Figure 5C shows PRO45 localization in this strain at a high resolution. Clearly, PRO45 simultaneously localizes to the nuclear envelope and to closely attached mitochondria.

FIG 5.

Localization of PRO45 by SIM. (A) Strain N861(pEGFP-45, pDsREDKDEL) was stained with DAPI, indicating localization of PRO45 to the nuclear envelope. (B) Strain N506(pEGFP-45) was costained with MitoTracker and ER-Tracker, revealing the simultaneous association of PRO45 with the nuclear envelope and mitochondria. Bars, 5 μm (A and B) and 1 μm (insets). (C) Association of EGFP-PRO45 with the ER, the nuclear envelope, and mitochondria at high resolution in strain N506. Note the close association of the mitochondrion with the nuclear envelope. (D) Hydrophobicity of tail anchors (TA) of human SLMAP isoforms and S. macrospora PRO45. The graph represents the hydrophobicity of the last 36 amino acids of each protein, including the transmembrane domains (boldface sequences) and the very C-terminal amino acids. SLMAP_TA1 and SLMAP_TA2 represent two alternative splice isoforms of SLMAP showing different subcellular localizations to the ER (SLMAP_TA1) and to both the ER and mitochondria (SLMAP_TA2) (63). Hydrophobicity was calculated using the Eisenberg normalized scale with a window size of 9; the relative weight for window edges was 100.

The localization of PRO45 to mitochondria prompted us to look for differences in mitochondrial structure in the wild type and the Δpro45 mutant. However, MitoTracker staining revealed no differences between the two strains, showing filamentous and fragmented mitochondria at the colony periphery and colony interior, respectively (Fig. 6, top two rows). In SIM images, mitochondria mostly appear to be fragmented, which might be due to fixation or to the usage of slim optical sections for reconstruction. To assess whether PRO45 colocalizes only with fragmented, possibly stressed mitochondria or also colocalizes with filamentous mitochondria at the colony periphery, we stained hyphae of a strain carrying EGFP-PRO45 with MitoTracker. As shown in Fig. 6 (bottom two rows), WF images show that PRO45 colocalizes with both morphotypes of mitochondria. Human PRO45 homolog SLMAP also localizes to ER structures, primarily the nuclear envelope, and to mitochondria, and this is due to different tail anchor domains generated by alternative splicing (22, 63). However, pro45 does not possess an intronic sequence in the vicinity of the TM-coding region. Further, no evidence of alternative splicing of the single intron was found in RNA-seq data from a previous analysis (58). Hydrophobic profiling of the PRO45 tail anchor revealed that it is highly similar to SLMAP tail anchor 2, which targets SLMAP to both ER structures and mitochondria (Fig. 5D) (63). These data are consistent with our microscopic observations.

FIG 6.

Mitochondrial morphology in the wild-type and the pro45 deletion and complemented strains. Hyphae of the wild type (WT), the Δpro45 mutant, and strain N508 (Δpro45::EGFP-PRO45) were stained with MitoTracker. Mitochondrial morphology and mitochondrial localization of PRO45 were assessed at the colony periphery (filamentous mitochondria) and the colony interior (fragmented mitochondria). DIC, differential inference contrast. Bar, 5 μm.

PRO45 localization to the ER and nuclear envelope requires STRIPAK subunits PRO11 and PRO22.

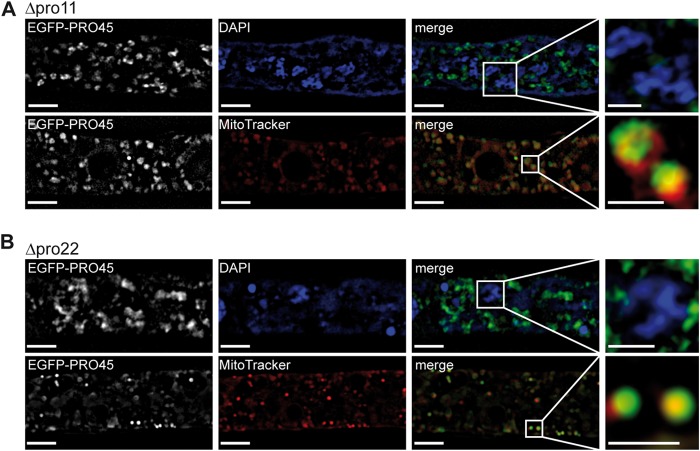

Recently, S. cerevisiae PRO45 homologs Far9p and Far10p were reported to remain at the nuclear envelope, even in the absence of all other Far complex components (51). However, in N. crassa, targeting of PRO45 homolog HAM-4 to the nuclear envelope depends on PRO11 homolog HAM-3 and PRO22 homolog HAM-2 (26). To assess PRO45 localization in mutants lacking the S. macrospora STRIPAK component PRO11 or PRO22, we transformed plasmids carrying EGFP-PRO45 into sterile Δpro11 and Δpro22 mutants (30).

SIM was performed using transformants (Table 1), and nuclei and mitochondria were stained with DAPI and MitoTracker, respectively (Fig. 7). Localization of EGFP-PRO45 in the Δpro11 mutant is shown in Fig. 7A. PRO45 was absent from the nuclear membrane in the Δpro11 mutant. However, mitochondrial localization of PRO45 was not affected in the pro11 deletion strain. This mitochondrial localization pattern was clearly different from the localization pattern of cytoplasmic GFP in SIM images (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Similar to the findings for the Δpro11 mutant, PRO45 localization to the nuclear envelope but not to mitochondria was lost in a Δpro22 background (Fig. 7B). Our data suggest that STRIPAK subunits PRO11 and PRO22 are required for nuclear envelope localization of PRO45 in S. macrospora, as described for N. crassa (26). Remarkably, the association of PRO45 with mitochondria was retained in the STRIPAK mutants. These data suggest that the mitochondrial association of PRO45 might be STRIPAK independent.

FIG 7.

Localization of PRO45 in Δpro11 and Δpro22 mutants by SIM. The Δpro11 and Δpro22 mutants were transformed with pEGFP-45 and stained with either DAPI or MitoTracker. (A) SIM shows that EGFP-PRO45 is absent from the nuclear envelope in the Δpro11 mutant but is still associated with mitochondria. (B) Similarly, PRO45 can be found only at the mitochondria and not at the nuclear envelope in the Δpro22 mutant. Bars, 5 μm and 1 μm (insets).

DISCUSSION

The STRIPAK complex is a highly conserved multiprotein complex containing phosphatases and kinases (21). Recently, a Sordaria STRIPAK complex that controls sexual development and cell fusion has been described (30). In this study, we showed that S. macrospora SLMAP homolog PRO45 is a component of this STRIPAK complex, plays a fundamental role in cell fusion and sexual propagation, and localizes to the ER and mitochondria.

The composition of STRIPAK complexes in different organisms seems to be diverse, with striatin, MOB3, PP2A scaffolding and catalytic subunits, and STRIP proteins being central components (21). For instance, SLMAP has been shown to be an accessory protein to human and N. crassa STRIPAK complexes but not to Drosophila dSTRIPAK (20, 24, 26). However, SLMAP homologs Far9p/Far10p of S. cerevisiae and Csc1p of S. pombe are integral components of the STRIPAK-equivalent Far and SIP complexes (16, 51). Using a TAP-MS approach, we showed that PRO45 is part of the S. macrospora STRIPAK complex and interacts with the striatin homolog PRO11 and SmMOB3. In N. crassa, SLMAP homolog HAM-4 coprecipitated all five STRIPAK components and was itself coprecipitated as prey by all five STRIPAK members (26), yet TAP-MS analysis with STRIP homolog PRO22 from S. macrospora did not yield any PRO45 peptides (30). However, this result may be due to the experimental approach that required two subsequent affinity purifications instead of the one-step purifications used for N. crassa (26). In human cells, interaction data were also dependent on the experimental approach. In FLAG-pulldown experiments, SLMAP was precipitated by striatins, MOB3, members of the GCKIII kinase family, PP2A subunits, and STRIP1. However, in TAP experiments, SLMAP reciprocally interacted only with MOB3 (20). Thus, the absence of other STRIPAK components in the PRO45 TAP-MS data does not necessarily mean that there is no complex formation of PRO45 with STRIPAK. In a previous study, for example, we found PRO22 to interact with PRO11, generating the link to PRO45 (Fig. 8). Thus, although the general composition of the STRIPAK complex and interactions between core components, i.e., PP2A scaffolding subunit PP2AA, PP2A catalytic subunit PP2Ac1, and PP2A regulatory subunit PRO11, seem to be conserved, interactions with accessory components may be species specific.

FIG 8.

Model of the S. macrospora STRIPAK complex. PRO45 and PRO22 associate STRIPAK components to the nuclear envelope, mitochondria, and other internal membrane systems (30), with PRO11 bridging both proteins. SmMOB3 interacts with both PRO45 and PRO11. Phosphatases and kinases in the fungal STRIPAK complex promote dephosphorylation and phosphorylation of target proteins, thereby regulating vegetative growth, hyphal fusion, and sexual propagation.

The function of SLMAPs in fungi seems to be diverse. The paralogs Far9p and Far10p of S. cerevisiae are both required for pheromone-mediated cell cycle arrest (17), and Far9p, also identified as Vps64p, has a defect in α-factor secretion (19). S. pombe Csc1p participates in SIN inactivation, and a csc1 deletion mutant shows septation defects (16). In N. crassa, HAM-4 is required for cell-to-cell fusion and, possibly, vacuolar morphology (18). In this study, we showed that S. macrospora Δpro45 has a severe developmental defect, in addition to the cell fusion phenotype. Like other pro mutants, the Δpro45 strain is unable to form perithecia. This is clearly different from the phenotype of an N. crassa Δham-4 strain that is fertile. However, slight developmental defects have been described, namely, a delay in protoperithecium formation and aberrant meiosis and ascospore formation in homozygous crosses (18).

Diverse domains have been annotated in SLMAP homologs; among them are the FHA domain, a phosphothreonine-specific protein binding motif. The FHA domain of mouse SLMAP has been found to be necessary, but not sufficient, for targeting of SLMAP to centrosomes (6). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms are still unknown. Results from this study show hyphal fusion deficiency and sterility in an S. macrospora strain with PRO45 from which FHA was deleted, as in the pro45 deletion strain. Interestingly, N. crassa ham-4 repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) mutants harboring a HAM-4 protein with a shortened FHA domain are self-fusion competent, whereas a ham-4 deletion mutant is not (18). In human cells, the FHA domain of SLMAP is required for binding mammalian Hippo homologs MST1 and MST2 (mammalian STE20-like kinases 1 and 2, respectively) (65). Taken together, these findings point to multiple important roles of the FHA domain in different developmental processes. However, at least in S. macrospora, these roles seem to be independent of the interaction of PRO45 with STRIPAK components PRO11 and SmMOB3 since both were copurified with PRO45ΔFHA-TAP.

Interestingly, the TM domain of PRO45 seems to have no developmental function. This is surprising, because the TA domain of tail anchor proteins, consisting of the C-terminal TM domain and the amino acids located at the very C terminus, is responsible for targeting these proteins to specific membranes (1–3). One explanation could be that we did not delete the complete TA but deleted only the TM domain of PRO45 and that the residual amino acids and/or PRO45 interaction partners are sufficient for targeting. Indeed, many mitochondrial proteins were identified in TAP-MS experiments with PRO45 as the bait (see Table S1 in the supplemental material); however, whether these candidates are true interaction partners remains to be elucidated.

In this study, we analyzed PRO45 localization by superresolution microscopy. Several superresolution microscopy methods have been developed, such as photoactivation localization microscopy (PALM), SIM, stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) (reviewed in reference 66). Although PALM, STED microscopy, and STORM give a higher optical resolution than SIM, they require photocontrollable fluorescent proteins. Thus, SIM is the only superresolution microscopy method that can be applied using conventional fluorescence proteins, such as GFP, and dyes (64). SIM has been applied in fungi, e.g., in the yeast S. cerevisiae, to analyze the ER-mitochondrion association in bud tips (67). However, as for the other superresolution methods, cells need to be fixed. Since fixation might lead to artifacts, localization data must be carefully rechecked by comparison with WF or confocal images. In this study, PRO45 localization to fragmented mitochondria by SIM could imply the binding of PRO45 only to stressed mitochondria; however, by WF microscopy, we showed colocalization with both fragmented and filamentous mitochondria (Fig. 6). Thus, here we report on the application of SIM for filamentous fungi and show that it is a highly convenient method to study the localization of a developmental protein with possible functions in organelle connections (see below).

A recurring theme is the function of SLMAP homologs as proteins that mediate membrane anchoring to and/or attachment of different membranes. Organelle contact sites have been described between, e.g., the inner nuclear membrane, ER, and vacuoles, between the ER and plasma membrane, and between the ER and mitochondria (reviewed in reference 68). Such associations are thought to facilitate communication between organelles as well as lipid and ion transfer. In the yeast S. cerevisiae, the ER-mitochondrion encounter structure (ERMES) complex localizes at ER-mitochondrion contact sites, tethering both organelles (69). ERMES, a homolog of which has not yet been identified in higher eukaryotes, was suggested to be involved in phospholipid exchange, calcium signaling, and mitochondrial physiology (70–72). Recently, ER-mitochondrion contact sites have been shown to play a role in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (73, 74).

In this study, we localized PRO45 to the ER and mitochondria. These and other data led to the hypothesis that the association of different organelles may be one function of STRIPAK. S. cerevisiae Far9p and Far10p are responsible for anchoring the Far complex at the ER (51). Human SLMAP has been described to localize to the sarcolemma and the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and it was proposed that homodimerization of differently localized SLMAPs mediates excitation-contraction coupling in mouse myocardia (8). Human SLMAP was also implicated in Golgi apparatus-centrosome connections (22). Similar to mammalian systems, PRO45 might function as a membrane organizer, bridging two organelles, the nuclear envelope and the outer mitochondrial membrane, to mediate signaling. This membrane bridging may also be required to target different STRIPAK subcomplexes to different cellular locations or to mediate STRIPAK-related and STRIPAK-unrelated functions of PRO45 in the same cell (Fig. 8). Of course, mitochondrial localization might also hint to a role in mitochondrial respiration; however, we excluded the possibility of such a function for PRO45 by high-resolution respirometry of the deletion mutant (S. Nordzieke, A. Hamann, H. D. Osiewacz, and I. Teichert, unpublished results).

Similar to the findings for N. crassa (26), localization of PRO45 to the nuclear envelope was absent in STRIPAK Δpro11 and Δpro22 mutants. Further data from N. crassa indicate that localization of STRIPAK components to the nuclear envelope may not even be sufficient to direct cell communication and cell differentiation (26). There, STRIPAK has been shown to be required for the nuclear accumulation of MAP kinase MAK1; however, MAK1 nuclear accumulation does not seem to be required for STRIPAK-related functions in cell-to-cell communication. It can be hypothesized that a correctly assembled STRIPAK complex tethers PRO45 to the ER, while the localization of PRO45 to mitochondria might be STRIPAK independent. STRIPAK-independent functions of distinct STRIPAK subunits have been described for other systems (reviewed in reference 21), and one example is the function of S. macrospora PRO22, but not other STRIPAK subunits, in ascogonial septation (57). However, PRO45 might still need interaction with STRIPAK to carry out its function at mitochondria. The analysis of STRIPAK complexes from both the animal and fungal kingdoms clearly reveals that STRIPAK composition and function are diverse. In fact, Frost et al. (22) referred to these functional differences as a “repurposing” of STRIPAK complexes. Scrutinizing the composition and regulation of different STRIPAK subcomplexes with distinct functions will be one of the major tasks for future studies.

In summary, we have characterized PRO45 as a STRIPAK-associated protein and, by establishing SIM, showed its localization at high resolution. Importantly, both fungal PRO45 and mammalian SLMAP are required for cell-to-cell fusion, underlining their high degree of functional conservation. It is therefore of major interest to further scrutinize different STRIPAK subcomplexes and to decipher the various roles of PRO45 in a fungal model system, a system that is highly suitable for unraveling underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms of key eukaryotic cellular processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bonn, Germany) to U.K. (PAK489, KU517/11-2).

We thank Regina Ricke and Susanne Schlewinski for excellent technical assistance and Gabriele Frenssen-Schenkel for help with graphical work. We thank C. Klämbt (Münster, Germany) for providing the Zeiss ELYRA S.1 system. We acknowledge Daniel Schindler and Christoph Krisp for experimental help.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00241-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wattenberg B, Lithgow T. 2001. Targeting of C-terminal (tail)-anchored proteins: understanding how cytoplasmic activities are anchored to intracellular membranes. Traffic 2:66–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgese N, Brambillasca S, Colombo S. 2007. How tails guide tail-anchored proteins to their destinations. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgese N, Fasana E. 2011. Targeting pathways of C-tail-anchored proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:937–946. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wigle JT, Demchyshyn L, Pratt MA, Staines WA, Salih M, Tuana BS. 1997. Molecular cloning, expression, and chromosomal assignment of sarcolemmal-associated proteins. A family of acidic amphipathic alpha-helical proteins associated with the membrane. J Biol Chem 272:32384–32394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzzo RM, Salih M, Moore ED, Tuana BS. 2005. Molecular properties of cardiac tail-anchored membrane protein SLMAP are consistent with structural role in arrangement of excitation-contraction coupling apparatus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288:H1810–H1819. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01015.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzzo RM, Sevinc S, Salih M, Tuana BS. 2004. A novel isoform of sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein (SLMAP) is a component of the microtubule organizing centre. J Cell Sci 117:2271–2281. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzzo RM, Wigle J, Salih M, Moore ED, Tuana BS. 2004. Regulated expression and temporal induction of the tail-anchored sarcolemmal-membrane-associated protein is critical for myoblast fusion. Biochem J 381:599–608. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nader M, Westendorp B, Hawari O, Salih M, Stewart AF, Leenen FH, Tuana BS. 2012. Tail-anchored membrane protein SLMAP is a novel regulator of cardiac function at the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302:H1138–H1145. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00872.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa T, Sato A, Marcou CA, Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ, Crotti L, Schwartz PJ, On YK, Park JE, Nakamura K, Hiraoka M, Nakazawa K, Sakurada H, Arimura T, Makita N, Kimura A. 2012. A novel disease gene for Brugada syndrome: sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein gene mutations impair intracellular trafficking of hNav1.5. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 5:1098–1107. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.969972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wielowieyski PA, Sevinc S, Guzzo R, Salih M, Wigle JT, Tuana BS. 2000. Alternative splicing, expression, and genomic structure of the 3′ region of the gene encoding the sarcolemmal-associated proteins (SLAPs) defines a novel class of coiled-coil tail-anchored membrane proteins. J Biol Chem 275:38474–38481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck AH, Lee CH, Witten DM, Gleason BC, Edris B, Espinosa I, Zhu S, Li R, Montgomery KD, Marinelli RJ, Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Jablons DM, Rubin BP, Fletcher CD, West RB, van de Rijn M. 2010. Discovery of molecular subtypes in leiomyosarcoma through integrative molecular profiling. Oncogene 29:845–854. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding H, Howarth AG, Pannirselvam M, Anderson TJ, Severson DL, Wiehler WB, Triggle CR, Tuana BS. 2005. Endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes correlates with deregulated expression of the tail-anchored membrane protein SLMAP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289:H206–H211. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00037.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fellenberg J, Saehr H, Lehner B, Depeweg D. 2012. A microRNA signature differentiates between giant cell tumor derived neoplastic stromal cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Lett 321:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demicco EG, Boland GM, Brewer Savannah KJ, Lusby K, Young ED, Ingram D, Watson KL, Bailey M, Guo X, Hornick JL, van de Rijn M, Wang WL, Torres KE, Lev D, Lazar AJ. 30 May 2014. Progressive loss of myogenic differentiation in leiomyosarcoma has prognostic value. Histopathology. doi: 10.1111/his.12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen K, Yang X, Wu L, Yu M, Li X, Li N, Wang S, Li G. 2013. Pinellia pedatisecta agglutinin targets drug resistant K562/ADR leukemia cells through binding with sarcolemmal membrane associated protein and enhancing macrophage phagocytosis. PLoS One 8:e74363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh NS, Shao N, McLean JR, Sevugan M, Ren L, Chew TG, Bimbo A, Sharma R, Tang X, Gould KL, Balasubramanian MK. 2011. SIN-inhibitory phosphatase complex promotes Cdc11p dephosphorylation and propagates SIN asymmetry in fission yeast. Curr Biol 21:1968–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemp HA, Sprague GF Jr. 2003. Far3 and five interacting proteins prevent premature recovery from pheromone arrest in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 23:1750–1763. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1750-1763.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonin AR, Rasmussen CG, Yang M, Glass NL. 2010. Genes encoding a striatin-like protein (ham-3) and a forkhead associated protein (ham-4) are required for hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol 47:855–868. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonangelino CJ, Chavez EM, Bonifacino JS. 2002. Genomic screen for vacuolar protein sorting genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 13:2486–2501. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goudreault M, D'Ambrosio LM, Kean MJ, Mullin MJ, Larsen BG, Sanchez A, Chaudhry S, Chen GI, Sicheri F, Nesvizhskii AI, Aebersold R, Raught B, Gingras AC. 2009. A PP2A phosphatase high density interaction network identifies a novel striatin-interacting phosphatase and kinase complex linked to the cerebral cavernous malformation 3 (CCM3) protein. Mol Cell Proteomics 8:157–171. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800266-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang J, Pallas DC. 2014. STRIPAK complexes: structure, biological function, and involvement in human diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 47:118–148. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frost A, Elgort MG, Brandman O, Ives C, Collins SR, Miller-Vedam L, Weibezahn J, Hein MY, Poser I, Mann M, Hyman AA, Weissman JS. 2012. Functional repurposing revealed by comparing S. pombe and S. cerevisiae genetic interactions. Cell 149:1339–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kean MJ, Ceccarelli DF, Goudreault M, Sanches M, Tate S, Larsen B, Gibson LC, Derry WB, Scott IC, Pelletier L, Baillie GS, Sicheri F, Gingras AC. 2011. Structure-function analysis of core STRIPAK proteins: a signaling complex implicated in Golgi polarization. J Biol Chem 286:25065–25075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ribeiro PS, Josue F, Wepf A, Wehr MC, Rinner O, Kelly G, Tapon N, Gstaiger M. 2010. Combined functional genomic and proteomic approaches identify a PP2A complex as a negative regulator of Hippo signaling. Mol Cell 39:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pracheil T, Thornton J, Liu Z. 2012. TORC2 signaling is antagonized by protein phosphatase 2A and the Far complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 190:1325–1339. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.138305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dettmann A, Heilig Y, Ludwig S, Schmitt K, Illgen J, Fleissner A, Valerius O, Seiler S. 2013. HAM-2 and HAM-3 are central for the assembly of the Neurospora STRIPAK complex at the nuclear envelope and regulate nuclear accumulation of the MAP kinase MAK-1 in a MAK-2-dependent manner. Mol Microbiol 90:796–812. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engh I, Nowrousian M, Kück U. 2010. Sordaria macrospora, a model organism to study fungal cellular development. Eur J Cell Biol 89:864–872. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kück U, Pöggeler S, Nowrousian M, Nolting N, Engh I. 2009. Sordaria macrospora, a model system for fungal development, p 17–39. In Anke T. (ed), The Mycota XV. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teichert I, Nowrousian M, Pöggeler S, Kück U. 2014. The filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora as a genetic model to study fruiting body development. Adv Genet 87:199–244. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800149-3.00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bloemendal S, Bernhards Y, Bartho K, Dettmann A, Voigt O, Teichert I, Seiler S, Wolters DA, Pöggeler S, Kück U. 2012. A homolog of the human STRIPAK complex controls sexual development in fungi. Mol Microbiol 84:310–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du Y, Shi Y, Yang J, Chen X, Xue M, Zhou W, Peng YL. 2013. A serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP2A catalytic subunit is essential for asexual development and plant infection in Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr Genet 59:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00294-012-0385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erental A, Harel A, Yarden O. 2007. Type 2A phosphoprotein phosphatase is required for asexual development and pathogenesis of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:944–954. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shim WB, Sagaram US, Choi YE, So J, Wilkinson HH, Lee YW. 2006. FSR1 is essential for virulence and female fertility in Fusarium verticillioides and F. graminearum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:725–733. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang CL, Shim WB, Shaw BD. 2010. Aspergillus nidulans striatin (StrA) mediates sexual development and localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum. Fungal Genet Biol 47:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pöggeler S, Kück U. 2004. A WD40 repeat protein regulates fungal cell differentiation and can be replaced functionally by the mammalian homologue striatin. Eukaryot Cell 3:232–240. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.1.232-240.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engh I, Nowrousian M, Kück U. 2007. Regulation of melanin biosynthesis via the dihydroxynaphthalene pathway is dependent on sexual development in the ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. FEMS Microbiol Lett 275:62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walz M, Kück U. 1995. Transformation of Sordaria macrospora to hygromycin B resistance: characterization of transformants by electrophoretic karyotyping and tetrad analysis. Curr Genet 29:88–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00313198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colot HV, Park G, Turner GE, Ringelberg C, Crew CM, Litvinkova L, Weiss RL, Borkovich KA, Dunlap JC. 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:10352–10357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker DM, Lundblad V. 2001. Introduction of DNA into yeast cells. Curr Protoc Mol Biol Chapter 13:Unit 13.7. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1307s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nowrousian M, Frank S, Koers S, Strauch P, Weitner T, Ringelberg C, Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, Kück U. 2007. The novel ER membrane protein PRO41 is essential for sexual development in the filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora. Mol Microbiol 64:923–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nowrousian M, Cebula P. 2005. The gene for a lectin-like protein is transcriptionally activated during sexual development, but is not essential for fruiting body formation in the filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora. BMC Microbiol 5:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P. 1992. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schindler D, Nowrousian M. 2014. The polyketide synthase gene pks4 is essential for sexual development and regulates fruiting body morphology in Sordaria macrospora. Fungal Genet Biol 68:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pöggeler S, Kück U. 2006. Highly efficient generation of signal transduction knockout mutants using a fungal strain deficient in the mammalian ku70 ortholog. Gene 378:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rech C, Engh I, Kück U. 2007. Detection of hyphal fusion in filamentous fungi using differently fluorescence-labeled histones. Curr Genet 52:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engh I, Würtz C, Witzel-Schlömp K, Zhang HY, Hoff B, Nowrousian M, Rottensteiner H, Kück U. 2007. The WW domain protein PRO40 is required for fungal fertility and associates with Woronin bodies. Eukaryot Cell 6:831–843. doi: 10.1128/EC.00269-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR III. 2001. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol 19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolters DA, Washburn MP, Yates JR III. 2001. An automated multidimensional protein identification technology for shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem 73:5683–5690. doi: 10.1021/ac010617e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pracheil T, Liu Z. 2013. Tiered assembly of the yeast Far3-7-8-9-10-11 complex at the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 288:16986–16997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahajan A, Yuan C, Lee H, Chen ES, Wu PY, Tsai MD. 2008. Structure and function of the phosphothreonine-specific FHA domain. Sci Signal 1:re12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.151re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walshaw J, Woolfson DN. 2001. Socket: a program for identifying and analysing coiled-coil motifs within protein structures. J Mol Biol 307:1427–1450. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nowrousian M, Teichert I, Masloff S, Kück U. 2012. Whole-genome sequencing of Sordaria macrospora mutants identifies developmental genes. G3 (Bethesda) 2:261–270. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernhards Y, Pöggeler S. 2011. The phocein homologue SmMOB3 is essential for vegetative cell fusion and sexual development in the filamentous ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Curr Genet 57:133–149. doi: 10.1007/s00294-010-0333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bloemendal S, Lord KM, Rech C, Hoff B, Engh I, Read ND, Kück U. 2010. A mutant defective in sexual development produces aseptate ascogonia. Eukaryot Cell 9:1856–1866. doi: 10.1128/EC.00186-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teichert I, Wolff G, Kück U, Nowrousian M. 2012. Combining laser microdissection and RNA-seq to chart the transcriptional landscape of fungal development. BMC Genomics 13:511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Punt PJ, Kramer C, Kuyvenhoven A, Pouwels PH, van den Hondel CA. 1992. An upstream activating sequence from the Aspergillus nidulans gpdA gene. Gene 120:67–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90010-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lichius A, Lord KM. 2014. Chemoattractive mechanisms in filamentous fungi. Open Mycol J 8:28–57. doi: 10.2174/1874437001408010028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fu C, Iyer P, Herkal A, Abdullah J, Stout A, Free SJ. 2011. Identification and characterization of genes required for cell-to-cell fusion in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 10:1100–1109. doi: 10.1128/EC.05003-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leeder AC, Jonkers W, Li J Y, Glass NL. 2013. Early colony establishment in Neurospora crassa requires a MAP kinase regulatory network. Genetics 195:883–898. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.156984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Byers JT, Guzzo RM, Salih M, Tuana BS. 2009. Hydrophobic profiles of the tail anchors in SLMAP dictate subcellular targeting. BMC Cell Biol 10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gustafsson MG, Shao L, Carlton PM, Wang CJ, Golubovskaya IN, Cande WZ, Agard DA, Sedat JW. 2008. Three-dimensional resolution doubling in wide-field fluorescence microscopy by structured illumination. Biophys J 94:4957–4970. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Couzens AL, Knight JD, Kean MJ, Teo G, Weiss A, Dunham WH, Lin ZY, Bagshaw RD, Sicheri F, Pawson T, Wrana JL, Choi H, Gingras AC. 2013. Protein interaction network of the mammalian Hippo pathway reveals mechanisms of kinase-phosphatase interactions. Sci Signal 6:rs15. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galbraith CG, Galbraith JA. 2011. Super-resolution microscopy at a glance. J Cell Sci 124:1607–1611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Swayne TC, Zhou C, Boldogh IR, Charalel JK, McFaline-Figueroa JR, Thoms S, Yang C, Leung G, McInnes J, Erdmann R, Pon LA. 2011. Role for cER and Mmr1p in anchorage of mitochondria at sites of polarized surface growth in budding yeast. Curr Biol 21:1994–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elbaz Y, Schuldiner M. 2011. Staying in touch: the molecular era of organelle contact sites. Trends Biochem Sci 36:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, Walter P. 2009. An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science 325:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kornmann B, Walter P. 2010. ERMES-mediated ER-mitochondria contacts: molecular hubs for the regulation of mitochondrial biology. J Cell Sci 123:1389–1393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.058636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michel AH, Kornmann B. 2012. The ERMES complex and ER-mitochondria connections. Biochem Soc Trans 40:445–450. doi: 10.1042/BST20110758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rowland AA, Voeltz GK. 2012. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts: function of the junction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13:607–625. doi: 10.1038/nrm3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stoica R, De Vos KJ, Paillusson S, Mueller S, Sancho RM, Lau KF, Vizcay-Barrena G, Lin WL, Xu YF, Lewis J, Dickson DW, Petrucelli L, Mitchell JC, Shaw CE, Miller CC. 2014. ER-mitochondria associations are regulated by the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and are disrupted by ALS/FTD-associated TDP-43. Nat Commun 5:3996. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schon EA, Area-Gomez E. 2010. Is Alzheimer's disease a disorder of mitochondria-associated membranes? J Alzheimers Dis 20(Suppl 2):S281–S292. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dinkel H, Van Roey K, Michael S, Davey NE, Weatheritt RJ, Born D, Speck T, Krüger D, Grebnev G, Kuban M, Strumillo M, Uyar B, Budd A, Altenberg B, Seiler M, Chemes LB, Glavina J, Sanchez IE, Diella F, Gibson TJ. 2014. The eukaryotic linear motif resource ELM: 10 years and counting. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D259–D266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. TMbase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler 374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klix V, Nowrousian M, Ringelberg C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Pöggeler S. 2010. Functional characterization of MAT1-1-specific mating-type genes in the homothallic ascomycete Sordaria macrospora provides new insights into essential and nonessential sexual regulators. Eukaryot Cell 9:894–905. doi: 10.1128/EC.00019-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.