Abstract

Background:

It is unclear whether more timely cancer diagnosis brings favourable outcomes, with much of the previous evidence, in some cancers, being equivocal. We set out to determine whether there is an association between time to diagnosis, treatment and clinical outcomes, across all cancers for symptomatic presentations.

Methods:

Systematic review of the literature and narrative synthesis.

Results:

We included 177 articles reporting 209 studies. These studies varied in study design, the time intervals assessed and the outcomes reported. Study quality was variable, with a small number of higher-quality studies. Heterogeneity precluded definitive findings. The cancers with more reports of an association between shorter times to diagnosis and more favourable outcomes were breast, colorectal, head and neck, testicular and melanoma.

Conclusions:

This is the first review encompassing many cancer types, and we have demonstrated those cancers in which more evidence of an association between shorter times to diagnosis and more favourable outcomes exists, and where it is lacking. We believe that it is reasonable to assume that efforts to expedite the diagnosis of symptomatic cancer are likely to have benefits for patients in terms of improved survival, earlier-stage diagnosis and improved quality of life, although these benefits vary between cancers.

Keywords: systematic review, diagnosis, delays, survival, stage

Symptomatic diagnosis of cancer is important and has been the subject of considerable innovation and intervention in recent years to achieve timelier and earlier-stage diagnosis (Emery et al, 2014); the English National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative has made a major contribution to this effort (Richards and Hiom, 2009; Richards, 2009a). We know that patients value timely diagnostic workup, and that later stage at diagnosis is one of the contributory factors to poor cancer outcomes (Richards, 2009b). However, it is less clear whether more timely cancer diagnosis brings favourable outcomes. Systematic reviews in breast cancer reported that delays of 3–6 months were associated with lower survival (Richards et al, 1999), and in colorectal cancer it was concluded that there were no associations between diagnostic delays and survival and stage (Ramos et al, 2007, 2008; Thompson et al, 2010). Other reviews have been published for gynaecological cancers (Menczer, 2000), bladder (Fahmy et al, 2006), testicular (Bell et al, 2006), lung (Jensen et al, 2002; Olsson et al, 2009), paediatric cancers (Brasme et al, 2012a, 2012b) and head and neck cancers (Goy et al, 2009; Seoane et al, 2012), all with equivocal findings. No review to date has undertaken this work in a range of different cancer types.

Longer time to diagnosis may be detrimental in several ways: a more advanced stage at diagnosis, poorer survival, greater disease-related and treatment-related morbidity and adverse psychological adjustment. Conversely, harm may be caused by earlier detection of cancers without improving survival (lead-time), and detection of slow-growing tumours not needing treatment (over-diagnosis) (Esserman et al, 2013). A scoping review, undertaken before the review reported here, showed that observational studies in many cancers reported no association or an inverse relationship between longer diagnostic times and better outcomes (Neal, 2009). We therefore undertook a systematic review of the literature aiming to determine whether there is an association between time to diagnosis, treatment and clinical outcomes, across all cancers for symptomatic presentations only.

Materials and methods

We undertook a systematic review in two phases. The original review was conducted in 2008–10, and the literature from inception of databases to February 2010 was searched; the update was conducted in 2013–14, and the literature from February 2010 to November 2013 was searched. The original review did not include breast or colorectal cancer (because of prior systematic reviews); however, these were included in the update (as we knew of more papers published in these cancers). The review adhered to principles of good practice (Egger et al, 2001; NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2001). Reporting is in line with the PRISMA recommendations (Moher et al, 2009).

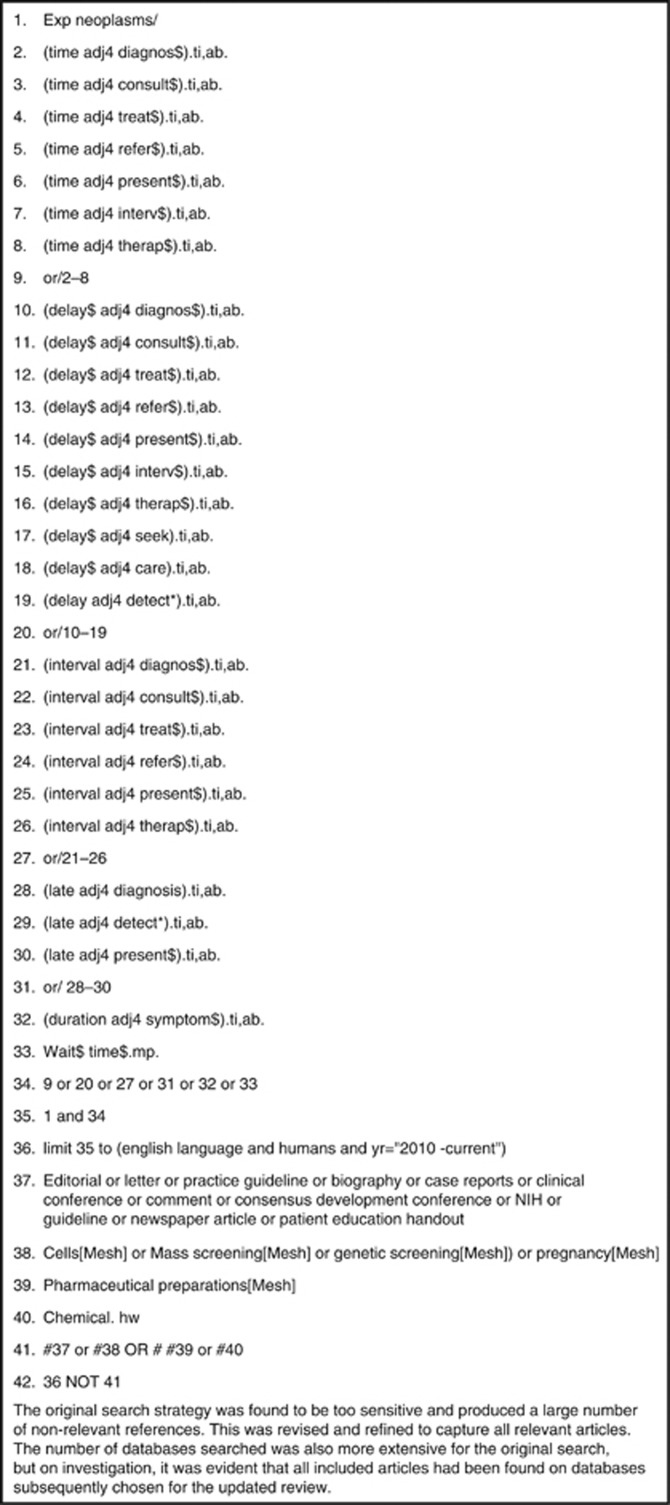

A search strategy was developed for Medline (Figure 1) and adapted for other search sources. A range of bibliographic databases were searched for relevant studies. These were as follows:

MEDLINE, MEDLINE in-process, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsychINFO

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Health Technology Assessment Database, NHS Economic Evaluation database.

Figure 1.

Search strategy (medline).

Reference lists of studies included in this and previous reviews were hand-searched for relevant studies.

One reviewer screened the titles and abstracts of all records for relevance, and assessed potentially relevant records for inclusion. A second reviewer checked the decisions; disagreements were resolved by discussion or, if necessary, by a third reviewer. A study or analysis was included in the review if it:

Reported patients with symptomatic diagnosis of primary cancer (screen- and biomarker-detected cancers were excluded).

Primarily aimed to determine the association of at least one time interval to diagnosis or treatment (patient, primary care, secondary care or a combination), allowing assessment against accepted definitions (Weller et al, 2012). The outcomes of interest were any measure of survival or mortality; any description of stage, including extent or severity of disease at diagnosis and response to treatment; or quality of life.

Was available as full text in English.

Data extraction for all included studies was done by one researcher and checked by another. We extracted data relating to the following:

Characteristics of included studies: study aim, population, location, setting, definitions of time intervals, data collection methods used and outcome measures.

Clinical outcomes: included the measure of association, associations of intervals with outcomes and reported interpretation.

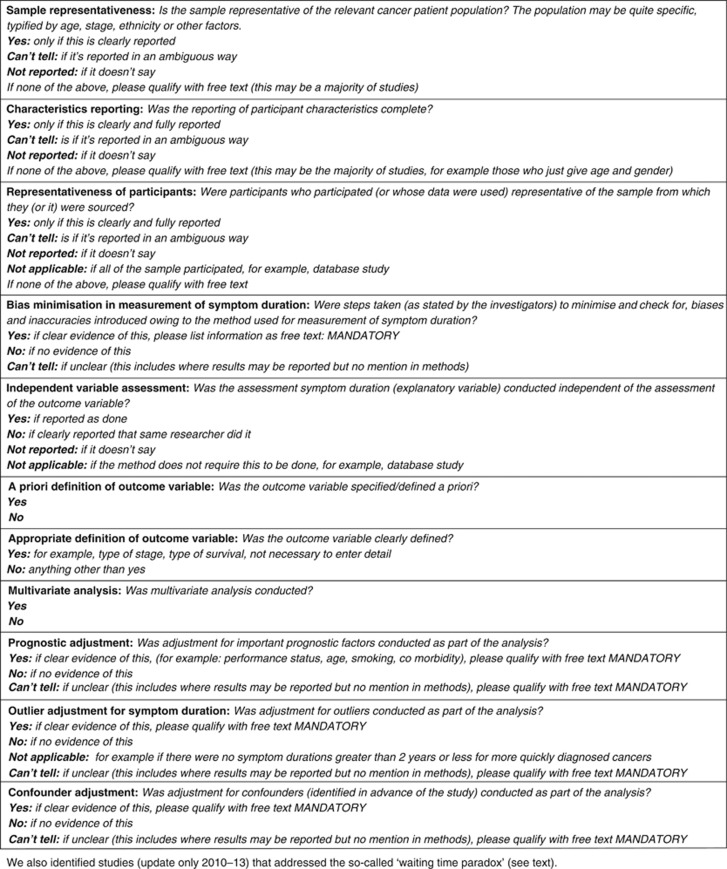

Bias assessment: we envisaged at the outset that there would be considerable variation between included studies in terms of study design, and that many may be of poor quality (Neal, 2009). We therefore considered that the assessment of methodological quality was especially important. However, at that time, there were no widely accepted checklists for checking the quality of prognostic studies, and there was little empirical evidence to support the importance of individual criteria, or study features, in affecting the reliability of study findings (Altman, 2001). Hence, we decided against the use of quality scoring, and to use a checklist instead of a scale. Judgements on the risk of bias were made according to a number of domains, using a generic list of questions within each domain (Figure 2), based primarily on a framework for assessing prognostic studies (Altman, 2001). For the updated review, and being aware of more recent literature on assessing the quality of prognostic studies, we decided to keep the original questions, as they were in line with the new Quality in Prognosis Studies tool (Hayden et al, 2006, 2013). In addition, in the update, we identified studies that addressed the so-called ‘waiting time paradox' (Crawford et al, 2002), which were likely to be of higher analytical quality. These were defined as follows: ‘articles that undertake an analysis or sub-analysis that specifically includes or excludes patients who are either diagnosed very quickly (e.g., within 4–8 weeks, although this will vary between cancers), or have very poor outcomes (e.g., deaths within a short time after diagnosis, e.g., within 4–8 weeks).' Agreement on inclusion in this subset of articles was done by two members of the study team. This is the ‘paradox' caused by the inclusion of patients with aggressive disease who invariably present early and have poor outcomes as a result of the aggressive disease, and is a form of confounding by indication.

Clinical outcomes: the measure of association, associations of intervals with outcomes and interpretation.

Figure 2.

Bias assessment tool.

We planned to undertake meta-analysis if there were sufficient homogenous studies reporting a similar outcome measure and the same interval for an individual cancer. Narrative synthesis was undertaken otherwise.

Results

Study selection

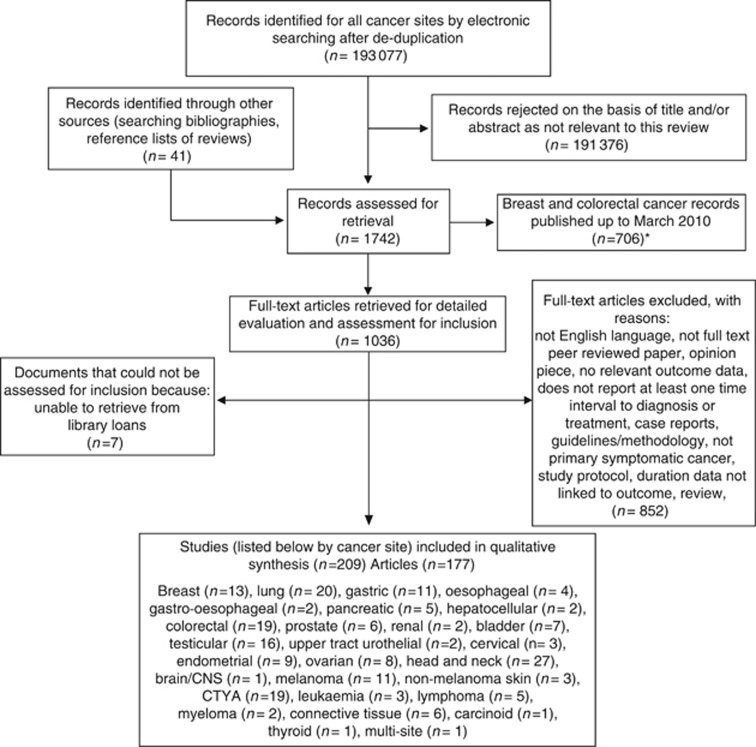

The number of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, included and reasons for exclusion are shown in Figure 3. Of the 1036 records identified for full-text review, 177 articles, reporting 209 studies, met the inclusion criteria and entered the narrative synthesis. A number of the articles reported data on more than one cancer, or more than one interval.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram. *Of those breast and colorectal cancer records published up to March 2010 (n=706) assessed for retrieval, 330 were retrieved and assessed for inclusion but were not included in the evaluation, as systematic reviews on these cancers had been recently published. The follow-up review, covering the period March 2010 to October 2013, included both breast and colorectal cancers in the qualitative synthesis.

Data collection in the included studies

Definition of time intervals

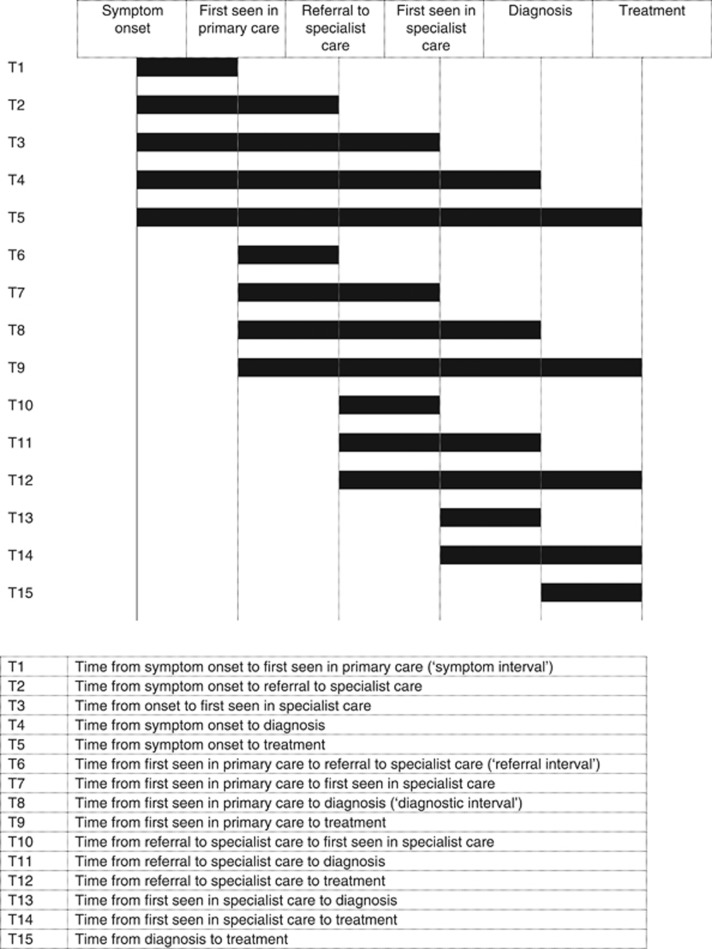

There were 15 different intervals reported in the included studies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Definitions of time interval.

Clinical and psychological outcomes

Data collection for the outcome measures was predominantly retrospective review of medical records (using a variety of the following: clinical, pathological, histological and imaging) and cancer registries.

Patient questionnaires were used for studies with psychological outcomes. Most studies used various measures of survival (or mortality) and/or stage as outcome measures.

Bias assessment

The bias assessment demonstrates the mixed quality of the studies (Supplementary Online Material). On a positive note, the characteristics and representativeness of the samples were reported in most articles, the definitions and appropriateness of time intervals were well reported and many studies undertook multivariable analysis. However, the representativeness of the samples was not reported in many articles, and few studies undertook confounder adjustment, prognostic adjustment or attempted bias minimisation. Only seven of the articles made an attempt to address the waiting time paradox (Tørring et al, 2011, 2012, 2013; Brasme et al, 2012a, 2012b; Elit et al, 2013; Gobbi et al, 2013; Pruitt et al, 2013). Hence, most studies failed to address the premise of confounding by indication–that is, the relationship between the diagnostic pathway (and hence the time interval) and prognosis.

Study characteristics

Of the 177 articles included, there were a total of 401 760 participants, with a range of 13 to 147 682 in individual study size (Supplementary Online Material). There were 88 European studies with 23 from the UK, 9 from Italy, 8 from Spain, 8 from the Netherlands, 7 from Denmark, 7 from Finland, 5 from France, 5 from Norway, 3 from Switzerland, 3 from Sweden, 3 from Germany, 2 from Poland and 1 each from Austria, Belgium, Romania, Greece and joint UK/Denmark. There were 18 studies from Asia, with 5 from India, 4 from Japan, 4 from China, 2 from Hong Kong, 2 from Malaysia and 1 from South Korea. There were 59 studies from the Americas, with 47 studies from the USA, 8 from Canada and 4 from Brazil. In addition, there were three from Turkey, two from Israel, two from Australia, one each from New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Libya, South Africa and one unspecified.

148 were based in specialist care 148 (106 single site, 38 multisite and 4 unspecified), 21 were population based, 3 were set in primary care, 3 database studies, 1 used hospital cancer registry data and 1 was unspecified. Study design varied hugely, and it included prospective and retrospective cohort studies, reviews of medical records, database analyses, patient surveys and interviews. The majority of the studies had retrospective designs.

Synthesis of main findings

The results of individual studies are presented in Supplementary Online Material. No meta-analyses were possible. The results are reported cancer by cancer. Studies are grouped under ‘children teenagers and young adults' where they reported at least a significant proportion of participants aged <25 years.

Summaries for each cancer are reported in Table 1. Studies that reported ‘positive' associations (i.e., where there was evidence of shorter intervals being associated with more favourable outcomes) are presented first, followed by studies that reported no associations, followed by those that reported ‘negative' associations (i.e., where there was evidence of shorter intervals being associated with less favourable outcomes). In each section, studies reporting survival outcomes (or mortality, but for simplicity just referred to as survival in the table) are presented before those reporting stage and other outcomes. A brief narrative for each cancer is provided below.

Table 1. Summary results from narrative synthesis, by cancer.

| Positive association | No association | Negative association |

|---|---|---|

|

Breast | ||

| Survival Diagnostic interval (Tørring et al, 2013) Treatment interval (Yun et al, 2012; Smith et al, 2013) | Survival Treatment interval (Brazda et al, 2010; McLaughlin et al, 2012; Eastman et al, 2013; Mujar et al, 2013; Redaniel et al, 2013; Sue et al, 2013) | None reported |

| Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Ermiah et al, 2012; Warner et al, 2012) | Stage Treatment interval (Wright et al, 2010; Wagner et al, 2011) | |

| Other outcomes Treatment interval and risk of recurrence (Eastman et al, 2013) | ||

|

Lung | ||

| Survival Diagnostic interval (Tørring et al, 2013) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Maguire et al, 1994) | Survival Symptom onset to treatment (Annakkaya et al, 2007) Patient interval (Loh et al, 2006) Diagnostic interval (Loh et al 2006; Pita-Fernandez et al, 2007; Skaug et al, 2011) Treatment interval (Diaconescu et al, 2011; Yun et al, 2012) Symptom onset to being seen in specialist care (Garcia-Barcala, 2012) | Survival Patient interval (Radzikowska et al, 2012) Treatment interval (Gonzalez-Barcala et al, 2010) |

| Stage Symptom onset to treatment (Christensen et al, 1997) Treatment interval (Brocken et al, 2012; Murai et al, 2012) | Stage Patient interval (Yilmaz et al, 2008; Tokuda et al, 2009) Diagnostic interval(Pita-Fernandez et al, 2007; Yilmaz et al, 2008) | Stage Diagnostic interval (Gould et al, 2008) Treatment interval (Salomaa et al, 2005) Symptom onset to treatment (Myrdal et al, 2004) Referral interval (Neal, 2007) First seen in secondary care to diagnosis (Brocken et al, 2012) |

| Other outcomes Symptom onset to diagnosis and quality of life (Mohan et al, 2006) | ||

|

Gastric | ||

| None reported | Survival Treatment interval (Yun et al, 2012) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Maguire et al, 1994; Martin et al, 1997; Windham et al, 2002; Arvanitakis et al, 2006) Patient interval (Lim et al, 1974) Primary care interval (Lim et al, 1974) | Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Maconi et al, 2003) Patient interval (Ziliotto et al, 1987) |

| Stage Diagnostic interval (Fernandez et al, 2002) Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | Stage Diagnostic interval (Haugstvedt et al, 1991) | |

|

Oesophageal | ||

| Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Martin et al, 1997) | Stage Diagnostic interval (Fernandez et al, 2002) Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | Stage Symptom onset to treatment (Wang et al, 2008) |

|

Gastro-oesophageal | ||

| Survival None reported | Survival Referral interval (Sharpe et al, 2010) | None reported |

| Other outcomes Treatment interval and morbidity and in-hospital mortality (Grotenhuis et al, 2010) | ||

|

Pancreatic | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Gobbi et al, 2013) Symptom onset to referral (Raptis et al, 2010) | Survival Treatment interval (Yun et al, 2012) | None reported |

| Stage Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | ||

| Other outcomes Diagnostic interval and resectability (McLean et al, 2013) | ||

|

Hepatocellular | ||

| Survival Treatment interval (Singal et al, 2013) | None reported | |

| Stage Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | ||

|

Colorectal | ||

| Survival Diagnostic interval (Tørring et al, 2011, 2012, 2013) Treatment interval (Gort et al, 2010–colon only; Yun et al, 2012–rectal only) | Survival Diagnostic interval (Pruitt et al, 2013) Referral interval (Zafar et al, 2011; Currie et al, 2012) Symptom onset to treatment (Thompson et al, 2011) First presentation to diagnosis (Singh et al, 2012) Treatment interval (Roland et al, 2013) | |

| Stage Treatment interval (Guzman-Laura et al, 2011) colon Referral interval (Valentin-Lopez et al, 2012) | Stage Symptom onset to treatment (Terhaar sive Droste et al, 2010; Cerdan-Santacruz et al, 2011; Deng et al, 2012) Referral interval (Ramsay et al, 2012) Treatment interval (Van Hout et al, 2011) Symptom onset to treatment (Van Hout et al, 2011) Patient interval (Cerdan-Santacruz et al, 2011; Van Hout et al, 2011) | Stage Treatment interval (Guzman-Laura et al, 2011) rectal |

| Other outcomes Patient interval and satisfaction (Tomlinson et al, 2012) | ||

|

Prostate | ||

| Survival Diagnostic interval (Tørring et al, 2013) Diagnosis to treatment (O'Brien et al, 2011) | Survival Diagnosis to treatment (Korets et al, 2012; Sun et al, 2012) Referral interval (Neal et al, 2007) | None reported |

| Stage Diagnosis to treatment (Korets et al, 2012; Sun et al, 2012) Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | ||

|

Testicular | ||

| Survival Patient interval (Hanson et al, 1993) Diagnostic interval (Huyghe et al, 2007; Moul et al, 1990–non-seminoma only) Symptom onset to treatment (Prout and Griffin, 1984; Medical Research Council Working Party, Testicular Tumours, 1985) | Survival Patient interval (Fossa et al, 1981) Symptom onset to treatment (Dieckmann et al, 1987) Symptom onset to treatment Meffan et al, 1991) Diagnostic interval (Moul et al, 1990; Harding et al, 1995–seminoma only; Fossa et al, 1981) | None reported |

| Stage Symptom onset to treatment (Ware et al, 1980; Wishnow et al, 1990) Patient interval (Ware et al, 1980; Chilvers et al, 1989) Diagnostic interval (Bosl et al, 1981; Moul et al, 1990; Huyghe et al, 2007–non-seminoma only) Patient interval (Hanson et al, 1993) | Stage Symptom onset to treatment (Dieckmann et al, 1987) Symptom onset to treatment Meffan et al, 1991) Diagnostic interval (Harding et al, 1995) | |

| Other outcomes Diagnostic interval and chance of complete remission (Akdas et al, 1986); and response to treatment (Scher et al, 1983) | Other outcomes Symptom onset to treatment and relapse rate (Napier and Rustin, 2000) | |

|

Renal | ||

| None reported | Stage Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | Stage Symptom onset to treatment (Holmang and Johansson, 2006) |

|

Bladder | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Hollenbeck et al, 2010) Symptom onset to referral (Wallace et al, 2002) | Survival Treatment interval (Gulliford et al, 1991) Referral interval (Wallace et al, 2002) Symptom onset to treatment (Mommsen et al, 1983) | None reported |

| Stage Diagnostic interval (Liedberg et al, 2003) | Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Maguire et al, 1994) Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | |

|

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma | ||

| Survival Diagnosis to treatment (Waldert et al, 2010; Sundi et al, 2012) | None reported | |

| Stage Diagnosis to treatment (Waldert et al, 2010) | ||

|

Cervical | ||

| Survival Treatment interval (Umezu et al, 2012) | None reported | |

| Stage Patient interval (Fruchter and Boyce, 1981) | Stage Primary care interval (Fruchter and Boyce, 1981) Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | |

|

Endometrial | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Menczer et al, 1995) | Survival Referral to treatment interval (Crawford et al, 2002) Diagnosis to treatment interval (Elit et al, 2013) | |

| Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Fruchter and Boyce, 1981; Franceschi et al, 1983; Obermair et al, 1996) | Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Pirog et al, 1997) Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | |

| Other outcomes Symptom onset to treatment and quality of life and satisfaction (Robinson et al, 2012) | ||

|

Ovarian | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Nagle et al, 2011) Referral interval (Neal et al, 2007) | ||

| Stage Patient interval (Smith and Anderson, 1985; Tokuda et al, 2009) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Fruchter and Boyce, 1981; Menczer et al, 2009; Nagle et al, 2011) | Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Lurie et al, 2010) | |

| Other outcomes Symptom onset to treatment and quality of life and satisfaction (Robinson et al, 2012) | ||

|

Head and neck | ||

| Survival Patient interval (Koivunen et al, 2001–pharyngeal; Teppo and Alho, 2008–pharyngeal and laryngeal cancers (separately)) Diagnostic interval (Alho et al, 2006–head and neck unspecified; Teppo et al, 2003–laryngeal; Teppo and Alho, 2008–laryngeal) Symptom onset to treatment (Hansen et al, 2004–laryngeal) Treatment interval (Sidler et al, 2010–nasopharyngeal) | Survival Patient interval (Teppo et al, 2003–laryngeal; Teppo and Alho, 2008–tongue) Diagnostic interval (Seoane et al, 2010–oral; Teppo and Alho, 2008–pharyngeal and tongue (separately); Koivunen et al, 2001–pharyngeal) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Wildt et al, 1995–oral) Symptom onset to treatment (McGurk et al, 2005–head and neck unspecified) Treatment interval (Caudell et al, 2011–head and neck unspecified; Brouha et al, 2000–laryngeal) | None reported |

| Stage Patient interval (Kumar et al, 2001–oral; Brouha et al, 2005b–oral and pharyngeal cancer (separately); Lee et al, 1997–nasopharyngeal; Sheng et al, 2008–nasopharyngeal; Tromp et al, 2005–head and neck unspecified; Tokuda et al, 2009–head and neck unspecified; Tromp et al, 2005–head and neck unspecified) Diagnostic interval (Allison et al, 1998–aerodigestive tract; Al-Rajhi et al, 2009–nasopharyngeal) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Allison et al, 1998–aerodigestive tract; Al-Rajhi et al, 2009–nasopharyngeal) Symptom onset to referral (Pitchers and Martin, 2006–oropharyngeal) | Stage Patient interval (Allison et al, 1998–upper aerodigestive tract; Al-Rajhi et al, 2009–nasopharyngeal; Brouha et al, 2005a–laryngeal cancer; Wildt et al, 1995–oral; Teppo et al, 2009–vestibular schwannoma) Diagnostic interval (Teppo et al, 2009–vestibular schwannoma; Ho et al, 2004–oropharyngeal) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Miziara et al, 1998–laryngeal; Scott et al, 2005–oral) Symptom onset to referral (Vernham and Crowther, 1994 head and neck unspecified) Symptom onset to treatment (McGurk et al, 2005–head and neck unspecified) | |

| Other outcomes Diagnostic interval and risk of recurrence (Teppo et al, 2005–laryngeal) | Other outcomes Patient interval and risk of recurrence (Teppo et al, 2005–laryngeal) | |

|

Brain/CNS | ||

| Other outcomes Symptom onset to diagnosis and progressive neurological deterioration (Balasa et al, 2012) | None reported | None reported |

|

Melanoma | ||

| Survival Patient interval (Temoshok et al, 1984, Montella et al, 2002) Diagnostic interval (Temoshok et al, 1984; Metzger et al, 1998; Montella et al, 2002; Tørring et al, 2013) | None reported | |

| Stage Patient interval (Richards et al, 1999) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Helsing et al, 1997) | Stage Patient interval (Cassileth et al, 1982, Schmid-Wendtner et al, 2002; Carli et al, 2003; Baade et al, 2006) Diagnostic interval (Cassileth et al, 1982, Schmid-Wendtner et al, 2002; Baade et al, 2006) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Krige et al, 1991; Baade et al, 2006) | |

|

Non-melanoma skin | ||

| Stage Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | None reported | |

| Other outcomes Symptom onset and presentation to specialist care and increase in tumour size (Alam et al, 2011) | Other outcomes Symptom onset to treatment and larger lesions (Renzi et al, 2010) | |

|

CTYA | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Marwaha et al, 2010b–leukaemia; Ferrari et al, 2010–soft tissue sarcomas) First seen in specialist care to diagnosis (Marwaha et al, 2010a–leukaemia) | Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Kameda-Smith et al, 2013–soft tissue sarcomas; Sethi et al, 2013–posterior fossa tumours) Diagnostic interval (Lins et al, 2012–leukaemia; Crawford et al, 2009–primary spinal cord tumours) Patient interval (Yang et al, 2009 –osteosarcoma) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Brasme et al, 2012a, 2012b–medulloblastoma; Loh et al, 2012–paediatric solid tumours; Butros et al, 2002–retinoblastoma) | Survival Patient interval (Kukal et al, 2009–brain tumours) First symptom to treatment (Erwenne and Franco, 1989–retinoblastoma) |

| Stage Diagnostic interval (Wallach et al, 2006–retinoblastoma) | Stage Patient interval (Yang et al, 2009 –osteosarcoma; Simpson et al, 2005–Ewing's sarcoma) Symptom onset to diagnosis and eye loss (Butros et al, 2002–retinoblastoma) | Stage Diagnostic interval (Crawford et al, 2009–primary spinal cord tumours; Halperin et al, 2001–medulloblastoma; Bacci et al, 1999–Ewing's sarcoma) |

| Other outcomes Symptom onset to treatment and extra-ocular disease (Erwenne and Franco, 1989–retinoblastoma) | Other outcomes Patient interval and eye loss (Goddard and Kingston, 1999–retinoblastoma) Treatment interval and relapse rate (Wahl et al, 2012–leukaemia) | |

|

Leukaemia | ||

| None reported | Survival Diagnostic interval (Friese et al, 2011 (chronic lymphocytic)) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Prabhu et al, 1986 (chronic myeloid)) Treatment interval (Bertoli et al, 2013 (acute myeloid)) | None reported |

|

Lymphoma | ||

| None reported | Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Jacobi et al, 2008 (follicular); Maguire et al, 1994 (unspecified); Norum, 1995 (Hodgkin's)) | Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Kim et al, 1995; Foulc et al, 2003 (both Sezary syndrome)) |

|

Myeloma | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Kariyawasan et al, 2007) | None reported | None reported |

| Other outcomes Symptom onset to diagnosis and complications at diagnosis (Kariyawasan et al, 2007; Friese et al, 2009) | ||

|

Connective tissue | ||

| Survival Symptom onset to treatment (Ruka et al, 1988 (soft tissue sarcoma)) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Saithna et al, 2008 (soft tissue sarcoma)) Symptom onset to diagnosis (Nakamura et al, 2011 (soft tissue sarcoma)) | Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Rougraff et al, 2007 (soft tissue sarcoma); Wurtz et al, 1999 (osteosarcoma) | None reported |

| Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Bacci et al, 2002 (osteosarcoma)) | ||

|

Carcinoid | ||

| None reported | Survival Symptom onset to diagnosis (Toth-Fejel and Pommier, 2004) | None reported |

| Stage Symptom onset to diagnosis (Toth-Fejel and Pommier, 2004) | ||

|

Thyroid | ||

| None reported | Stage Patient interval (Tokuda et al, 2009) | None reported |

|

Multisite | ||

| Survival Diagnostic interval (Tørring et al, 2013 (breast, lung, colorectal, prostate and melanoma combined) | None reported | None reported |

For breast cancer, four studies reported positive associations, including one of the studies that addressed the waiting time paradox, and was able to demonstrate the effect of different diagnostic intervals on mortality (Tørring et al, 2013). The remainder reported no associations.

The lung studies had mixed findings, with similar numbers of studies reporting positive, negative and no associations, across a range of different time intervals. However, one of the studies reporting a positive association with mortality for diagnostic intervals addressed the waiting time paradox (Tørring et al, 2013).

For colorectal cancer, although many studies reported no associations, more studies reported a positive, rather than a negative, association. Indeed, four studies addressing the waiting time paradox were included, three of which reported a positive association (Tørring et al, 2011, 2012, 2013) and one a negative association (Pruitt et al, 2013). Of the upper gastrointestinal cancers, most studies reported no association, and more reported a negative, rather than a positive, association. For pancreatic cancer, two of the five studies reported a positive association, one of which addressed the waiting time paradox (Gobbi et al, 2013). The other three studies reported no association.

Two of the prostate studies reported a positive association for survival/mortality, one of which addressed the waiting time paradox (Tørring et al, 2013); the others reported no association. Two of the bladder studies reported a positive association; the others reported no association. For testicular cancer, 15 studies reported positive associations, and the remainder had no associations.

For gynaecological cancers, of the four studies examining cervix, one reported a positive association; the others reported no association. For endometrial and ovarian cancers, there were similar numbers of studies with positive, negative and no associations. One of the endometrial studies that reported a negative association addressed the waiting time paradox (Elit et al, 2013).

For head and neck cancers (pharyngeal, laryngeal, oral and others), there were a large number of studies and these were equally divided between those reporting a positive association and those reporting no association. No studies reported a negative association.

For melanoma, eight studies reported positive associations, one of which addressed the waiting time paradox (Tørring et al, 2013); the remainder reported no associations. For non-melanoma skin, two studies reported positive associations and one reported no association.

There were a large number of studies covering the various cancers in children, teenagers and young adults. The findings of these were very mixed, with the biggest group showing no associations, and smaller but similar number of studies reporting both positive and negative associations. One of the ‘no association' studies addressed the waiting time paradox (Brasme et al, 2012a, 2012b).

For lymphoma, three studies reported no association or a negative association. For leukaemia, the three studies reported no associations. There were only two studies in myeloma, although both of these reported positive outcomes. For the various connective tissue cancers, three studies each reported a positive association and no association. The other cancer groups (brain/central nervous system, carcinoid, hepatocellular, renal, thyroid, upper tract urothelial carcinoma and multisite) only had one or two included studies.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This review is unique in that it has assessed the literature for a range of different cancer types, and hence we are able to make recommendations for policy practice and research that are not limited to one cancer (or group of cancers). The number of included studies in this review has shown the importance of this question to patients, clinicians and researchers. However, even within specific cancer types, there is only moderate consensus as to the nature of any associations between various time intervals in the diagnostic process and clinical outcomes, with some studies showing no associations, some studies showing better outcomes with shorter time intervals and some the opposite. There are more reports of an association between times to diagnosis and outcomes for breast, colorectal, head and neck, testicular and melanoma, with reports from a smaller number of studies for pancreatic, prostate and bladder cancers. The time intervals in the studies varied, making it impossible to draw consensus as to which intervals may be more, or less, important. Moreover, the methodological quality of many of these papers is mixed, despite a recent consensus paper on design and reporting of such studies (Weller et al, 2012). There is some evidence from papers published more recently that address the waiting time paradox in their analyses (Tørring et al, 2011, 2012, 2013; Brasme et al, 2012a, 2012b; Elit et al, 2013, Gobbi et al, 2013, Pruitt et al, 2013), with most, but not all, of these reporting longer intervals being associated with poorer outcomes, particularly mortality. This is important and begins to provide more robust evidence about the relationship between time to diagnosis and outcomes.

Findings within the context of the literature

The previous cancer-specific reviews (Menczer, 2000; Jensen et al, 2002; Bell et al, 2006; Fahmy et al, 2006; Ramos et al, 2007, 2008; Goy et al, 2009; Olsson et al, 2009; Thompson et al, 2010; Brasme et al, 2012a, 2012b), with the exception of the breast cancer (Richards et al, 1999), and to a lesser extent head and neck (Seoane et al, 2012), have been largely equivocal, probably because of the poor quality of the included studies. Our findings are largely in keeping with these reviews, although we have provided much more evidence than previous reviews for testicular cancer (Bell et al, 2006) and head and neck cancers (Goy et al, 2009). We have also identified more recent and probably higher-quality papers providing better evidence for colorectal cancer than covered in previous reviews (Ramos et al, 2007, 2008; Thompson et al, 2010). We provide review findings for the first time for many cancers. We are also aware of further articles being published since the end date of our review. For example, one of these replicated the methods of one of the papers in our review (Tørring et al, 2011) on a sample of 958 colorectal cancers in Scotland, and reported that longer diagnostic intervals did not adversely affect cancer outcomes (Murchie et al, 2014). Another has reported that time to diagnosis in 436 Ewing tumours in France was not associated with metastasis, surgical outcome or survival (Brasme et al, 2014). One of our main findings, of the poor quality of reporting of time to diagnosis studies, replicates the findings of a recent paediatric systematic review (Launay et al, 2013).

Strengths and weaknesses

This is the largest and most comprehensive review in this field, and the first ‘all-cancer' systematic review. The huge heterogeneity in both the outcomes and the time intervals used, within each cancer site, precluded meta-analyses. Another systematic review has recently reported similar difficulty in comparisons between studies (Lethaby et al, 2013). As previously stated, the review only contains studies in colorectal and breast cancer for 2010–13, and only these studies identified during the second round of searches were assessed to determine whether their analyses addressed the waiting time paradox. Survival, or mortality, is the most objective outcomes for these studies. However, many of the included studies in the review reported stage, or some other proxy. This may explain why stage and survival outcomes differ. Stage categorisation also varied, and some of the studies may be affected by post-hoc upstaging. A further problem with the literature is that of confounding by indication. Symptoms of more advanced cancer are likely to present differently and be investigated more promptly, as are patients presenting with so-called ‘red-flag' symptoms. We were unable to assess for publication bias; indeed, if there was any publication bias, we cannot predict in which direction this would act.

Implications for policy, practice and research

Our main conclusion from this review is that we believe that it is reasonable to assume that efforts to expedite the diagnosis of symptomatic cancer are likely to have benefits for patients in terms of earlier-stage diagnosis, improved survival and improved quality of life. The amount of benefit varies between cancers; at present, there is more evidence for breast, colorectal, head and neck, testicular and melanoma, with evidence from a smaller number of studies for pancreatic, prostate and bladder cancers. There is either insufficient evidence or equivocal findings in the other cancers. The findings need replicating in using similar analytical methods, ideally also to address how much of a difference expedited diagnosis of different cancers would make on outcomes, and at which points in the diagnostic journey matters most. Until we have well-designed and well-analysed prospective studies to answer this question, it is difficult to determine the likely effect of interventions to reduce patient and diagnostic intervals on outcomes. This knowledge would inform the development of targeted intervention studies, to improve outcomes.

Hence, we recommend that policy, and clinicians, should continue the current emphasis on expediting symptomatic diagnosis, at least for most cancers. This can be achieved by clinicians having a high index of suspicion of cancer, the use of diagnostic technologies and rapid access to diagnostic investigations and fast-track pathways for assessment (Rubin et al, 2014). Finally, we recommend the need for more high-quality research in the area for a number of reasons. First, we suspect that many clinicians continue to believe that there are no associations between time and clinical outcomes.

A considerable number of studies fail to address basic issues of bias and thus equate the absence of evidence with evidence of absence. Second, it is likely that more timely diagnosis may have a greater or lesser impact between different cancers. This is important to ascertain, because it will inform policy and practice. We recommend, where possible, re-analysis of pooled (and similar) data from some of the studies included in this review, and new studies using linked data sets, across all cancers, such that similar analyses can be conducted between cancers. We also recommend that such studies should ideally focus on survival or mortality as the outcome, as this is the ‘gold-standard' outcome, although stage is also a valuable end point. There is also a dearth of studies reporting patient experience; we therefore recommend further work that examined the relationship between patient perceptions of ‘delay' and quality of life and psychological outcomes. Suggested key quality criteria for future studies are summarised in Box 1. Other work should focus on the organisation and function of health services, and subsequent time intervals and outcomes. Furthermore, we recommend that, wherever possible, this work should be conducted and reported in keeping within the recommendations of the Aarhus Statement (Weller et al, 2012).

Box 1. Key quality criteria for studies that examine the relationship between time intervals in cancer diagnosis and outcomes.

Good studies will report the definition of intervals in compliance with definitions in the Aarhus statement (Weller et al, 2012). The most common intervals reported are as follows:

Patient interval – the time from when bodily changes and/or first symptoms are noticed to presentation of this change or symptom to a health care professional

Diagnostic interval – the date from first presentation to a health care professional to diagnosis

Referral interval – the date from referral to specialist care to being seen in specialist care

Good studies will report key dates in the diagnostic journey in a standardised way, with a full description. This includes, for example, the following:

Dates when patients first notices bodily changes or symptoms and when they decide to seek help

Date of first presentation of potential cancer symptom – including how such symptoms were defined

Date of diagnosis – clear reporting of how this date was obtained and what date it actually represents (e.g., date of tissue diagnosis, date when patient informed)

Dates of referral / investigation – including definitions of which were included and why

Good studies will fully describe appropriate data collection methods for time intervals. These will vary by interval, and different approaches to data collection (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, medical records, database studies) will give different answers. Data collection from patients is preferred for studies measuring patient intervals. Precise details regarding data collection methods are preferred.Good studies will fully describe and justify outcome measures. Mortality or survival is preferred, but some measure of stage (or other measure of disease severity or treatment modality) is also a useful endpoint. Studies capturing patient experience and quality of life and psychological outcomes are also needed.

Good studies will use a design that addresses bias and confounding (including confounding by indication); this includes measures to address the waiting time paradox.

Acknowledgments

The original study and the update were funded by Cancer Research UK (grants C8350/A8870 and C8350/A17915, through EDAG–Early Diagnosis Advisory Group). RDN also receives funding from Public Health Wales and Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board. We thank other members of the ABC-DEEP consortium who did not contribute directly to this review but gave valuable advice throughout the study. We also thank others who contributed to the original review. We also thank staff at Cancer Research UK for their support and feedback throughout the review. Last, we thank Emma Kennerley for administrative support. We acknowledge that two of the co-authors (RDN and MLT) were also authors of papers included in the review. These papers were independently assessed by other members of the research team. The updated review is registered with PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014006301).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary Material

References

- Akdas A, Kirkali Z, Remzi D. The role of delay in stage Iii testicular tumors. Int Urol Nephrol. 1986;18:181–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02082606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M, Goldberg LH, Silapunt S, Gardner ES, Strom SS, Rademaker AW, Margolis DJ. Delayed treatment and continued growth of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alho O, Teppo H, Mantyselka P, Kantola S. Head and neck cancer in primary care: presenting symptoms and the effect of delayed diagnosis of cancer cases. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174:779–784. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P, Franco E, Black M, Feine J. The role of professional diagnostic delays in the prognosis of upper aerodigestive tract carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(97)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rajhi N, El-Sebaie M, Khafaga Y, Al-Zahrani A, Mohamed G, Al-Amro A. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Saudi Arabia: clinical presentation and diagnostic delay. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:1301–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG.2001Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables Systematic Reviews in Health Care: meta-analysis in ContextEgger M, Smith GD, Altman DG (eds)2nd edBMJ Books: London [Google Scholar]

- Annakkaya A, Arbak P, Balbay O, Bilgin C, Erbas M, Bulut I. Effect of symptom-to-treatment interval on prognosis in lung cancer. Tumori. 2007;93:61–67. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis C, Nikopoulos A, Giannoulis E, Theoharidis A, Georgilas V, Fotiou H, Tourkantonis A. The impact of early or late diagnosis on patient survival in gastric cancer in Greece. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;39:355–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baade P, English D, Youl P, McPherson M, Elwood J, Aitken J. The relationship between melanoma thickness and time to diagnosis in a large population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1422–1427. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.11.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci G, Di Fiore M, Rimondini S, Baldini N. Delayed diagnosis and tumor stage in Ewing's sarcoma. Oncol Rep. 1999;6:465–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci G, Ferrari S, Longhi A, Forni C, Zavatta M, Versari M, Smith K. High-grade osteosarcoma of the extremity: differences between localized and metastatic tumors at presentation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:27–30. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasa AF, Gherasim DN, Gherman B. Clinical evolution of primary intramedullary tumors in adults. Rom J Neurol. 2012;11:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bell D, Morash C, Dranitsaris G, Izawa J, Short T, Klotz LH, Fleshner N. Does prolonging the time to testicular cancer surgery impact long-term cancer control: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Urol. 2006;13:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoli S, Berard E, Huguet F, Huynh A, Tavitian S, Vergez F, Dobbelstein S, Dastugue N, Mansat-De Mas V, Delabesse E, Duchayne E, Demur C, Sarry A, Lauwers-Cances V, Laurent G, Attal M, Recher C. Time from diagnosis to intensive chemotherapy initiation does not adversely impact the outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:2618–2626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-454553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosl G. J, Vogelzang N, Goldman A, Fraley E, Lange P, Levitt S, Kennedy B. Impact of delay in diagnosis on clinical stage of testicular cancer. Lancet. 1981;2:970–972. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasme JF, Chalumeau M, Oberlin O, Valteau-Couanet GasparN. Time to diagnosis of Ewing tumours in children and adolescents is not associated with metastasis or survival: a prospective multi-center study of 436 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1935–1940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.8058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasme JF, Grill J, Doz F, Lacour B, Valteau-Couanet D, Gaillard S, Delalande O, Aghakhani N, Puget S, Chalumeau M. Long time to diagnosis of medulloblastoma in children is not associated with decreased survival or with worse neurological outcome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasme JF, Morfouace M, Grill J, Martinot A, Amalberti R, Bons-Letouzey C, Chalumeau M. Delays in the diagnosis of paediatric cancers a systematic review and comparison with expert testimony in lawsuits. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e445–e459. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazda A, Estroff J, Euhus D, Leitch AM, Huth J, Andrews V, Moldrem A, Rao R. Delays in time to treatment and survival impact in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17 (Suppl 3:291–296. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocken P, Kiers Berni AB, Looijen-Salamon MG, Dekhuijzen PNR, Smits-van der Graaf C, Peters-Bax L, de Geus-Oei L, van der Heijden HFM. Timeliness of lung cancer diagnosis and treatment in a rapid outpatient diagnostic program with combined 18FDG-PET and contrast enhanced CT scanning. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouha X, Op De Coul B, Terhaard C, Hordijk G. Does waiting time for radiotherapy affect local control of T1N0M0 glottic laryngeal carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:215–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouha X, Tromp D, de Leeuw J, Hordijk G, Winnubst J. Laryngeal cancer patients: analysis of patient delay at different tumor stages. Head Neck. 2005;27:289–295. doi: 10.1002/hed.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouha X, Tromp D, Hordijk G, Winnubst J, de Leeuw J. Oral and pharyngeal cancer: analysis of patient delay at different tumor stages. Head Neck. 2005;27:939–945. doi: 10.1002/hed.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butros L, Abramson D, Dunkel I. Delayed diagnosis of retinoblastoma: analysis of degree, cause, and potential consequences. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E45. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli P, De Giorgi V, Palli D, Maurichi A, Mulas P, Orlandi C, Imberti G, Stanganelli I, Soma P, Dioguardi D, Catricalá C, Betti R, Cecchi R, Bottoni U, Bonci A, Scalvenzi M, Giannotti B. Dermatologist detection and skin self-examination are associated with thinner melanomas results from a survey of the italian multidisciplinary group on melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:607–612. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassileth B, Clark W, Heiberger R, March V, Tenaglia A. Relationship between patients early recognition of melanoma and depth of invasion. Cancer. 1982;49:198–200. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820101)49:1<198::aid-cncr2820490138>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudell J, Locher J, Bonner J. Diagnosis-to-treatment interval and control of locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:282–285. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdan-Santacruz C, Cano-Valderrama O, Cardenas-Crespo S, Torres-Garcia A, Cerdan-Miguel J. Colorectal cancer and its delayed diagnosis: have we improved in the past 25 years. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:458–463. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000900004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers C, Saunders M, Bliss J, Nicholls J, Horwich A. Influence of delay in diagnosis on prognosis in testicular teratoma. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:126–128. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen E, Harvald T, Jendresen M, Aggestrup S, Petterson G. The impact of delayed diagnosis of lung cancer on the stage at the time of operation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12:880–884. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(97)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Zaninovic A, Santi M, Rushing EJ, Olsen CH, Keating RF, Vezina G, Kadom N, Packer RJ. Primary spinal cord tumors of childhood: effects of clinical presentation, radiographic features, and pathology on survival. J Neurooncol. 2009;95:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9925-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford S, Davis J, Siddiqui N, de Caestecker L, Gillis C, Hole D, Penney G. The waiting time paradox: Population based retrospective study of treatment delay and survival of women with endometrial cancer in Scotland. Br Med J. 2002;325:196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie A, Evans J, Smith N, Brown G, Abulafi A, Swift R. The impact of the two-week wait referral pathway on rectal cancer survival. Colorectal Dis. 2012;4:848–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, An W, Gao J, Yin J, Cai Q, Yang M, Hong S, Fu X, Yu E, Xu X, Zhu W, Li Z. Factors influencing diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a hospital-based survey in china. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaconescu R, Lafond C, Whittom R. Treatment delays in non-small cell lung cancer and their prognostic implications. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1254–1259. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318217b623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann K, Becker T, Bauer H. Testicular tumors: presentation and role of diagnostic delay. Urol Int. 1987;42:241–247. doi: 10.1159/000281948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman A, Tammaro Y, Moldrem A, Andrews V, Huth J, Euhus D, Leitch M, Rao R. Outcomes of delays in time to treatment in triple negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1880–1885. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2835-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG.(eds) (2001Systematic Reviews in Health Care: meta-analysis in Context2nd ednBMJ Books: London [Google Scholar]

- Elit L, O'Leary E, Pond G, Seow H. Impact of wait times on survival for women with uterine cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;51:67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery J, Shaw K, Williams B, Maaza D, Fallon-Ferguson J, Varlow M, Trevena L. The role of primary care in early detection and follow-up of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermiah E, Abdalla F, Buhmeida A, Larbesh E, Pyrhonen S, Collan Y. Diagnosis delay in Libyan female breast cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:452. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwenne CM, Franco EL. Age and lateness of referral as determinants of extra-ocular retinoblastoma. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1989;10:179–184. doi: 10.3109/13816818909009874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer. An opportunity for improvement. JAMA. 2013;310:797–798. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy NM, Mahmud S, Aprikian AG. Delay in the surgical treatment of bladder cancer and survival: systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1176–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E, Porta M, Malats N, Belloc J, Gallén M. Symptom-to-diagnosis interval and survival in cancers of the digestive tract. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2434–2440. doi: 10.1023/a:1020535304670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A, Miceli R, Casanova M, Meazza C, Favini F, Luksch R, Catania S, Fiore M, Morosi C, Mariani L. The symptom interval in children and adolescents with soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2010;116:177–183. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossa DF, Klepp O, Elgio RF, Eliassen G, Melsom H, Urnes T, Wang M. The effect of patient's and doctor's delay in patients with malignant germ cell tumours. Int J Androl. 1981;4:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1981.tb00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulc P, N'Guyen JM, Dréno B. Prognostic factors in Sezary syndrome: a study of 28 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1152–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi S, La Vecchia C, Gallus G, Decarli A, Colombo E, Mangioni C, Tognoni G. Delayed diagnosis of endometrial cancer in Italy. Cancer. 1983;51 (6:1176–1178. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830315)51:6<1176::aid-cncr2820510634>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese CR, Abel GA, Magazu LS, Neville BA, Richardson LC, Earle CC. Diagnostic delay and complications for older adults with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:392–400. doi: 10.1080/10428190902741471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese CR, Earle CC, Magazu LS, Brown JR, Neville BA, Hevelone ND, Richardson LC, Abel GA. Timeliness and quality of diagnostic care for medicare recipients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2011;117:1470–1477. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruchter RG, Boyce J. Delays in diagnosis and stage of disease in gynecologic cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 1981;4:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi PG, Bergonzi M, Comelli M, Villano L, Pozzoli D, Vanoli A, Dionigi P. The prognostic role of time to diagnosis and presenting symptoms in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard AG, Kingston JE. Delay in diagnosis of retinoblastoma: Risk factors and treatment outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1320–1323. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.12.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, Garcia-Prim JM, Alvarez-Dobano JM, Moldes-Rodriguez M, Garcia-Sanz MT, Pose-Reino A, Valdes-Cuadrado L. Effect of delays on survival in patients with lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12:836–842. doi: 10.1007/s12094-010-0606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gort M, Otter R, Plukker JTM, Broekhuis M, Klazinga NS. Actionable indicators for short and long term outcomes in rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1808–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MK, Ghaus SJ, Olsson JK, Schultz EM. Timeliness of care in veterans with non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2008;133:1167–1173. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goy J, Hall SF, Feldman-Stewart D, Groome P. Diagnostic delay and disease stage in head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:889–898. doi: 10.1002/lary.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhuis BA, van Hagen P, Wijnhoven BPL, Spaander MCW, Tilanus HW, van Lanschot JJB. Delay in diagnostic workup and treatment of esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:476–483. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford MC, Petruckevitch A, Burney PG. Survival with bladder cancer, evaluation of delay in treatment, type of surgeon, and modality of treatment. Br Med J. 1991;303:437–440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6800.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Laura KP, Bolibar RI, Alepuz MT, Gonzalez D, Martin M. Impact on the care and time to tumor stage of a program of rapid diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:13–19. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin EC, Watson DM, George SL. Duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis is related inversely to presenting disease stage in children with medulloblastoma. Cancer. 2001;91:1444–1450. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010415)91:8<1444::aid-cncr1151>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen O, Larsen S, Bastholt L, Godballe C, Jørgensen KE. Duration of symptoms: impact on outcome of radiotherapy in glottic cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PR, Belitsky P, Millard OH, Lannon SG. Prognostic factors in metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumours. Can J Surg. 1993;36:537–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding M, Paul J, Kaye SB. Does delayed diagnosis or scrotal incision affect outcome for men with non-seminomatous germ cell tumours. Br J Urol. 1995;76:491–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugstvedt TK, Viste A, Eide GE, Soreide O. Patient and physician treatment delay in patients with stomach cancer in Norway is it important. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:611–619. doi: 10.3109/00365529109043635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:427–437. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JA, van der Windt D, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsing P, Faye R, Langmark F. Cutaneous malignant melanoma. Correlation between tumor characteristics and diagnostic delay in Norwegian patients. Eur J Dermatol. 1997;7:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Ho T, Zahurak M, Koch WM. Prognostic significance of presentation-to-diagnosis interval in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:45–51. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Ye Z, Hollingsworth JM, Skolarus TA, Kim SP, Montie JE, Lee CT, Wood DP, Miller DC. Delays in diagnosis and bladder cancer mortality. Cancer. 2010;116:5235–5242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmang S, Johansson SL. Impact of diagnostic and treatment delay on survival in patients with renal pelvic and ureteral cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40:479–484. doi: 10.1080/00365590600864093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyghe E, Muller A, Mieusset R, Bujan L, Bachaud JM, Chevreau C, Plante P, Thonneau P. Impact of diagnostic delay in testis cancer: results of a large population-based study. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1710–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi N, Rogers TB, Peterson BA. Prognostic factors in follicular lymphoma: a single institution study. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:185–193. doi: 10.3892/or.20.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AR, Mainz J, Overgaard J. Impact of delay on diagnosis and treatment of primary lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2002;41:147–152. doi: 10.1080/028418602753669517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda-Smith MM, White MAJ, George EJS, Brown JIM. Time to diagnosis of paediatric posterior fossa tumours: an 11-year West of Scotland experience 2000-2011. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27:364–369. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.741731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariyawasan CC, Hughes DA, Jayatillake MM, Mehta AB. Multiple myeloma: causes and consequences of delay in diagnosis. QJM. 2007;100:635–640. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Bishop K, Varghese A, Hoppe RT. Prognostic factors in erythrodermic mycosis fungoides and the sezary syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen P, Rantala N, Hyrynkangas K, Jokinen K, Alho OP. The impact of patient and professional diagnostic delays on survival in pharyngeal cancer. Cancer. 2001;92:2885–2891. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011201)92:11<2885::aid-cncr10119>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korets R, Seager CM, Pitman MS, Hruby GW, Benson MC, McKiernan JM. Effect of delaying surgery on radical prostatectomy outcomes: a contemporary analysis. Br J Urol Int. 2012;110:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krige JE, Isaacs S, Hudson DA, King HS, Strover RM, Johnson CA. Delay in the diagnosis of cutaneous malignant melanoma. A prospective study in 250 patients. Cancer. 1991;68:2064–2068. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911101)68:9<2064::aid-cncr2820680937>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukal K, Dobrovoljac M, Boltshauser E, Ammann RA, Grotzer MA. Does diagnostic delay result in decreased survival in paediatric brain tumours. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Heller RF, Pandey U, Tewari V, Bala N, Oanh KT. Delay in presentation of oral cancer: a multifactor analytical study. Natl Med J India. 2001;14:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay E, Morfouace M, Deneux-Tharaux C, Gras le-Guen C, Ravaud P, Chalumeau M. Quality of reporting of studies evaluating time to diagnosis: a systematic review in paediatrics. Arch Dis Child. 2013;99:244–250. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AWM, Foo W, Law SC, Poon YF, Sze WM, O SK, Tung SY, Lau WH. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma–presenting symptoms and duration before diagnosis. Hong Kong Med J. 1997;3:355–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lethaby CD, Picton S, Kinsey SE, Phillips R, van Laar M, Feltbower RG. A systematic review of time to diagnosis in children and young adults with cancer. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:349–355. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedberg F, Anderson H, Månsson A, Månsson W. Diagnostic delay and prognosis in invasive bladder cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37:396–400. doi: 10.1080/00365590310006246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim BS, Dennis CR, Gardner B, Newman J. Analysis of survival versus patient and doctor delay of treatment in gastrointestinal cancer. Am J Surg. 1974;127:210–214. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(74)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lins MM, Amorim M, Vilela P, Viana M, Ribeiro RC, Pedrosa A, Lucena-Silva N, Howard SC, Pedrosa F. Delayed diagnosis of leukemia and association with morbid-mortality in children in Pernambuco, Brazil. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e271–e276. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182580bea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh AHP, Aung L, Ha C, Tan A-M, Quah TC, Chui C-H. Diagnostic delay in pediatric solid tumors: a population based study on determinants and impact on outcomes. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:561–565. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh LC, Chan LY, Tan RY, Govindaraju S, Ratnavelu K, Kumar S, Raman S, Vijayasingham P, Thayaparan T. Time delay and its effect on survival in Malaysian patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma. Malays J Med Sci. 2006;13:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie G, Wilkens LR, Thompson PJ, Matsuno RK, Carney ME, Goodman MT. Symptom presentation in invasive ovarian carcinoma by tumor histological type and grade in a multiethnic population: a case analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maconi G, Kurihara H, Panizzo V, Russo A, Cristaldi M, Marrelli D, Roviello F, de Manzoni G, Di Leo A, Morgagni P, Bechi P, Bianchi Porro G, Taschieri AM. Gastric cancer in young patients with no alarm symptoms: focus on delay in diagnosis, stage of neoplasm and survival. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1249–1255. doi: 10.1080/00365520310006360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire A, Porta M, Malats N, Gallén M, Piñol JL, Fernandez E. Cancer survival and the duration of symptoms–an analysis of possible forms of the risk-function. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:785–792. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin IG, Young S, Sue-Ling H, Johnston D. Delays in the diagnosis of oesophagogastric cancer: a consecutive case series. Br Med J. 1997;314:467–470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7079.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha RK, Kulkarni KP, Bansal D, Trehan A. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia masquerading as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: diagnostic pitfall and association with survival. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:249–254. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha RK, Kulkarni KP, Bansal D, Trehan A. Pattern of mortality in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: experience from a single center in northern India. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:366–369. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e0d036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk MC, Chan C, Jones J, O'regan E, Sherriff M. Delay in diagnosis and its effect on outcome in head and neck cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JM, Anderson RT, Ferketich AK, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R, Paskett ED. Effect on survival of longer intervals between confirmed diagnosis and treatment initiation among low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4493–4500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.39.7695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SR, Karsanji D, Wilson J, Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Pasieka J, Ball C, Bathe OF. The effect of wait times on oncological outcomes from periampullary adenocarcinomas. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:853–858. doi: 10.1002/jso.23338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research Council Work Party, Testicular Tumours Prognostic factors in advanced non-seminomatous germ-cell testicular tumours results of a multicenter study. Lancet. 1985;1:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffan PJ, Delahunt B, Nacey JN. The value of early diagnosis in the treatment of patients with testicular cancer. NZ Med J. 1991;104:393–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menczer J. Diagnosis and treatment delay in gynecological malignancies: does it affect outcome. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2000;10:89–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2000.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menczer J, Chetrit A, Sadetzki S. The effect of symptom duration in epithelial ovarian cancer on prognostic factors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:797–801. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menczer J, Krissi H, Chetrit A, Gaynor J, Lerner L, Ben-Baruch G, Modan B. The effect of diagnosis and treatment delay on prognostic factors and survival in endometrial carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:774–778. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger S, Ellwanger U, Stroebel W, Schiebel U, Rassner G, Fierlbeck G. Extent and consequences of physician delay in the diagnosis of acral melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1998;8:181–186. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199804000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miziara ID, Cahali MB, Murakami MS, Figueiredo LA, Guimaraes JR. Cancer of the larynx: correlation of clinical characteristics, site of origin, stage, histology and diagnostic delay. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 1998;119:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan A, Mohan C, Bhutani M, Pathak AK, Pal H, Das C, Guleria R. Quality of life in newly diagnosed patients with lung cancer in a developing country: is it important. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15:293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mommsen S, Aagaard J, Sell A. Presenting symptoms, treatment delay and survival in bladder cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1983;17:163–167. doi: 10.3109/00365598309180162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montella M, Crispo A, Grimaldi M, De Marco MR, Ascierto PA, Parasole R, Melucci MT, Silvestro P, Fabbrocini G. An assessment of factors related to tumor thickness and delay in diagnosis of melanoma in Southern Italy. Prev Med. 2002;35:271–277. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moul JW, Paulson DF, Dodge RK, Walther PJ. Delay in diagnosis and survival in testicular cancer: Impact of effective therapy and changes during 18 years. J Urol. 1990;143:520–523. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujar M, Dahlui M, Yip CH, Taib NA. Delays in time to primary treatment after a diagnosis of breast cancer: does it impact survival. Prev Med. 2013;56:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai T, Shibamoto Y, Baba F, Hashizume C, Mori Y, Ayakawa S, Kawai T, Takemoto S, Sugie C, Ogino H. Progression of non-small-cell lung cancer during the interval before stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:463–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie P, Raja EA, Brewster DH, Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Robertson R, Samuel L, Gray N, Lee AJ. Time from presentation in primary care to treatment of symptomatic colorectal cancer: effect on disease stage and survival. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:461–469. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal G, Lambe M, Hillerdal G, Lamberg K, Agustsson T, Ståhle E. Effect of delays on prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 2004;59:45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle CM, Francis JE, Nelson AE, Zorbas H, Luxford K, de Fazio A, Fereday S, Bowtell DD, Green AC, Webb PM. Reducing time to diagnosis does not improve outcomes for women with symptomatic ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2253–2258. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Matsumine A, Matsubara T, Asanuma K, Uchida A, Sudo A. The symptom-to-diagnosis delay in soft tissue sarcoma influence the overall survival and the development of distant metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:771–775. doi: 10.1002/jso.22006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier MP, Rustin GJ. Diagnostic delay and risk of relapse in patients with stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumour followed on active surveillance. Br J Urol Int. 2000;86:486–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal RD. Do diagnostic delays in cancer matter. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S9–S12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal RD, Allgar VL, Ali N, Leese B, Heywood P, Proctor G, Evans J. Stage, survival and delays in lung, colorectal, prostate and ovarian cancer: comparison between diagnostic routes. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:212–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2001Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews2nd ednNHS CRD, University of York: York, UK [Google Scholar]

- Norum J. The effect of diagnostic delay in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:2707–2710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermair AE, Hanzal E, Schreiner-Frech I, Buxbaum P, Bancher-Todesca D, Thoma M, Kurz C, Vavra N, Gitsch G, Sevelda P. Influence of delayed diagnosis on established prognostic factors in endometrial cancer. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:947–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien D, Loeb S, Carvalhal GF, McGuire BB, Kan D, Hofer MD, Casey JT, Helfand BT, Catalona WJ. Delay of surgery in men with low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;185:2143–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson JK, Schultz EM, Gould MK. Timeliness of care in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review. Thorax. 2009;64:749–756. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.109330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirog EC, Heller DS, Westhoff C. Endometrial adenocarcinoma–Lack of correlation between treatment delay and tumor stage. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67:303–308. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pita-Fernandez S, Montero-Martinez C, Pértega-Diaz S, Verea-Hernando H. Relationship between delayed diagnosis and the degree of invasion and survival in lung cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;56:820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers M, Martin C. Delay in referral of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma to secondary care correlates with a more advanced stage at presentation, and is associated with poorer survival. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:955–958. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu M, Kochupillai V, Sharma S, Ramachandran P, Sundaram KR, Bijlani L, Ahuja RK. Prognostic assessment of various parameters in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 1986;58:1357–1360. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860915)58:6<1357::aid-cncr2820580629>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout GR, Griffin PP. Testicular tumors: delay in diagnosis and influence on survival. Am Fam Physician. 1984;29:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt SL, Harzke AJ, Davidson NO, Schootman M. Do diagnostic and treatment delays for colorectal cancer increase risk of death. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:961–977. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radzikowska E, Roszkowski-Sliz K, Glaz P. The impact of timeliness of care on survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2012;80:422–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Campillo C, Llobera J, Aguiló A. Relationship of diagnostic and therapeutic delay with survival in colorectal cancer: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2467–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Llobera J, Ruiz A. Lack of association between diagnostic and therapeutic delay and stage of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay G, MacKay C, Nanthakumaran S, Craig WL, McAdam TK, Loudon MA. Urgency of referral and its impact on outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e375–e377. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raptis DA, Fessas C, Belasyse-Smith P, Kurzawinski TR. Clinical presentation and waiting time targets do not affect prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Surgeon. 2010;8:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaniel MT, Martin RM, Cawthorn S, Wade J, Jeffreys M. The association of waiting times from diagnosis to surgery with survival in women with localised breast cancer in England. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:42–49. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi C, Mastroeni S, Passarelli F, Mannooranparampil TJ, Caggiati A, Potenza C, Pasquini P. Factors associated with large cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MA, Grob JJ, Avril MF, Delaunay M, Thirion X, Wolkenstein P, Souteyrand P, Dreno B, Bonerandi JJ, Dalac S, Machet L, Guillaume JC, Chevrant-Breton J, Vilmer C, Aubin F, Guillot B, Beylot-Barry M, Lok C, Raison-Peyron N, Chemaly P. Melanoma and tumor thickness: challenges of early diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:269–274. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MA. The National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative in England: assembling the evidence. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S1–S4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MA. The size of the prize for earlier diagnosis of cancer in England. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S125–S129. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MA, Hiom S. Diagnosing cancer earlier: evidence for a national awareness and early diagnosis initiative. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S1–S129. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KM, Christensen KB, Ottesen B, Krasnik A. Diagnostic delay, quality of life and patient satisfaction among women diagnosed with endometrial or ovarian cancer: a nationwide Danish study. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1519–1525. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]