Elucidation of the mechanisms of assembly of subcellular structures is often an elusive goal. The large number of component parts and the intricate ways in which they interact make experimental analysis a significant challenge and, in particular, frustrate attempts at traditional reductionist analysis. Frequently, key insights come from thoughtful cell biological observations that identify the most important steps in assembly. In the best cases, not only do these observations provide critical clues to old problems, but they also generate novel areas of investigation. An example of a finding that does both of these things comes from the work of van Ooij et al. (36a), published in this issue, who used careful cell biological analysis to uncover a novel dimension of the process by which bacterial spores assemble their external armor plating. These authors found that the deposition of external proteins on the spore surface is unexpectedly dynamic, pointing towards as-yet-unknown regulatory mechanisms controlling spore formation.

SPORE FUNDAMENTALS

Bacterial spores are marvels of nature. They are formed by bacilli and clostridia in response to starvation during an approximately 8-h developmental process, called sporulation, that is controlled by a complex cascade of cellular events (29). The result is a dormant, highly resistant cell that can endure almost any stress that nature has to offer. Spores can persist in the dormant state for very long and perhaps even geological time scales (28, 37). Nonetheless, the spore is not insensitive to its surroundings. Rather, it is continuously poised to react to the reintroduction of even minute amounts of nutrients to the milieu. The result is the almost immediate conversion of the spore back to an actively growing cell, a process known as germination.

These remarkable properties have motivated intensive study of spore formation and resistance since the first published description of spores in 1874 (21). With the advent of molecular approaches and, subsequently, advanced cell biological approaches, spore formation has become a well-developed model for elucidating fundamental mechanisms of development and cellular assembly (34). It is in the context of the assembly of the outermost spore structures that van Ooij et al. have made their contribution.

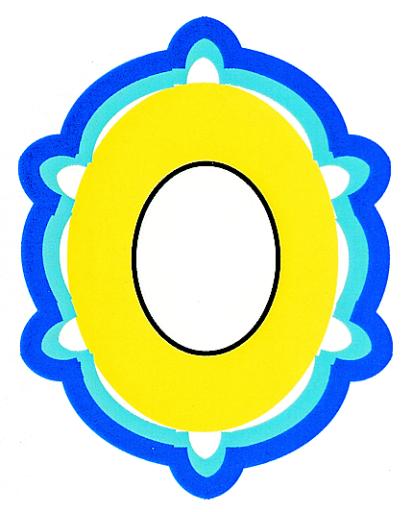

To appreciate these findings, a brief review of Bacillus subtilis spore ultrastructure is needed. All Bacillus spores have a common architecture (1, 18) (Fig. 1). At the center is the core, a relatively dry compartment that houses the spore DNA. Surrounding this is a membrane (called the inner membrane) and then a thick layer of peptidoglycan called the cortex. The cortex, in turn, is encased in a complex protein shell called the coat, which is the focus of this discussion. (An additional membrane set, the outer membrane, may also be present between the cortex and coat [9], and it is not illustrated in Fig. 1.) The coat has critical roles in protecting the spore from a variety of toxic molecules (6, 25, 32, 33, 39, 40) and in facilitating germination (1, 3, 4, 9). The coat is very likely to have additional functions as well, including the ability to act as an elastic material (7, 10) and the ability to perform enzymatic reactions (14, 15, 19, 24, 26).

FIG. 1.

Diagram of a B. subtilis spore in cross section. The outer and inner coat layers are indicated by dark blue and light blue, respectively. The thick yellow layer is the cortex, which surrounds the inner membrane, indicated by a black line. At the center is the core, which is white.

A COMPLEX ASSEMBLY PROCESS

We also need to consider how the spore is built. Early in sporulation, the starving cell's cytoplasm is divided by a specialized septum into large and small compartments, known as the mother cell and the forespore, respectively (29) (Fig. 2A). Following this, the rim of the septum, where it meets the mother cell envelope, migrates in the direction of the forespore so as to pinch off a protoplast. Coat proteins, which are synthesized in the mother cell cytoplasm, are deposited first on the mother cell side of the septum and later on the engulfed forespore surface.

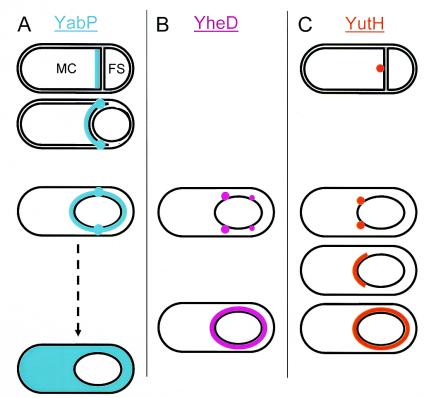

FIG. 2.

Patterns of localization of coat protein-GFP fusions during spore formation. Spore formation proceeds from top to bottom. The cells in a row are at approximately equivalent stages. (A) YabP-GFP. Early in spore formation, immediately after the septum appears, YabP-GFP (blue) localizes to the mother cell side of the septum (top cell). Mother cell (MC) and forespore (FS) compartments are indicated. As forespore engulfment continues (next cell down), foci (blue dots) appear at the leading edge of the septum. In fully engulfed forespores, the foci are located on either side of the short axis of the forespore (next cell down). YabP-GFP is delocalized prior to mother cell lysis (bottom cell). (B) YheD-GFP. After engulfment, four foci (pink) are present, on either side of the short axis of the forespore, suggesting that there are two rings (upper cell). The sizes of the dots indicate relative levels of fluorescence. These rings become a contiguous shell (lower cell). (C) YutH-GFP. A focus (orange) is present after septum formation (top cell). This focus becomes a ring after forespore engulfment (next cell down) and then a cap at the mother cell pole (next cell down). Finally, the cap becomes a complete shell (bottom cell).

Initial interest in the coat as a model system for macromolecular assembly was motivated in large part by its morphological complexity (1, 38). In B. subtilis, thin-section electron microscopy has revealed multiple layers in the coat, which are organized into two major sets: the lightly staining inner coat, which has distinctive fine lamellae, and a darkly staining outer coat, whose sublayers are relatively coarse. Analysis of the coat surface by scanning electron microscopy (5, 8) and atomic force microscopy (7) has shown that the predominant features are ridges, most of which run along the long axis of the spore. Not surprisingly, the coat is biochemically complex. It is composed largely of protein (22) and is comprised of as many as 60 polypeptide species (23, 24), most of which are unique to the bacilli and clostridia. From studies of about 30 of the B. subtilis coat proteins, a preliminary model of coat assembly has emerged (9, 11, 17, 36). This model reveals the importance of a subset of coat proteins that guide the deposition of coat proteins from the mother cell cytoplasm into the appropriate coat layers, as well as direct the appearance of the ridges on the coat surface (7). One of these morphogenetic proteins (SpoIVA [12, 31, 35]) attaches the coat to the underlying spore surface; another (CotE [41]) is responsible for nucleating the formation of the outer layer. From cell biological analyses, it is clear that in many if not most cases, each species of coat protein ultimately forms a shell around the forespore or, in some cases, an incomplete shell, resulting in what appear to be caps at the forespore poles (12, 13). The interconnections between coat proteins are also becoming better understood. We now know the identities of several directly interacting coat proteins (16, 42) and two of the coat proteins on the surface (20, 27). Overall, the model defines the major morphological steps in coat formation, identifies a significant part of the complex network of coat protein interactions, and pinpoints coat proteins with pivotal roles in assembly.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

As satisfying as the model is, it tells only part of the story. For example, it gives little insight into the precise sequence of events that occur during the deposition of any given coat protein. Detailed descriptions of these steps are essential, as it is at this level that we will ultimately understand the molecular interactions that drive coat assembly. van Ooij et al. used meticulous light microscopic examination and genetic manipulation to address this deficit. They built strains bearing fusions of the recently identified coat proteins YabP, YheD, and YutH (13) to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and monitored their assembly into the coat over time by using fluorescence microscopy. The striking result is that these proteins do not coalesce into shells in one step. Instead, and quite unexpectedly, the localization pattern of each protein is distinct and dynamic. YabP-GFP, which is synthesized just after the cell divides into mother cell and forespore compartments, localizes to the septum (Fig. 2A). As septum migration proceeds, however, relatively intense foci of fluorescence, in addition to the layer of fluorescence at the septum, appear at the leading edge of the engulfing septum, where it meets the mother cell. After engulfment is complete, the two foci reside opposite each other, along the short axis of the forespore. This suggests the presence of a ring, which appears as two dots when it is viewed in projection. The hypothesis that the two foci are part of a ring of fluorescence in three dimensions was confirmed by deconvolution methods. In addition to this ring, a shell of fluorescence encircling the spore appears at this stage. Formation of the shell, but not formation of the ring, depends on a coat protein encoded by a gene immediately upstream of yabP, called YabQ (2). Intriguingly, YabP-GFP is lost from the forespore prior to release from the mother cell.

Even more striking than the localization of YabQ is the localization of YheD. After forespore engulfment, YheD-GFP localizes to four foci that appear to correspond to two rings that are parallel to, but on either side of, the short axis of the forespore (Fig. 2B). The mother cell pole-proximal foci are brighter than the foci towards the forespore pole. Later, a contiguous shell surrounding the forespore appears, and the rings are lost. The final fusion that was examined, YutH-GFP, shows yet a third distinct pattern of localization. Early in sporulation, a sole focus appears at the septum (Fig. 2C). After engulfment, two foci at the extreme mother cell pole of the forespore appear, suggesting that there is a ring at this polar location. Soon after this, the ring becomes a cap. Finally, a shell covering most of the forespore forms.

These remarkable patterns of localization raise a number of intriguing questions. First, what mechanisms guide the dynamic deposition of these proteins? Although as-yet-unidentified proteins are likely to be involved in the initial localization of at least some coat proteins (30) (and, in the case of YabP, were specifically shown to be involved by van Ooij et al.), there is still the question of how any protein can distinguish one location on the forespore surface from another location. Perhaps the process of forespore engulfment is in some manner intrinsically asymmetric, leaving behind telltale markers of position that are recognized by coat proteins. Regardless of how coat proteins initially target to specific locations on the forespore surface, it seems that different mechanisms guide the formation of rings that appear after initial deposition. The latter events may be the result of the intrinsic properties of the proteins in question, as well as the overall dynamics of coat assembly.

A second question is the purpose, if any, of the dynamic aspect of coat assembly characterized by van Ooij et al. One possibility is that the properties of the coat would be fundamentally different if the coat proteins were not assembled in these patterns. Alternatively, these patterns may not so much be critical to the final functioning of the coat but rather may form part of a process that coordinates the simultaneous assembly of a large number coat proteins and prevents deposition of one coat protein species from interfering with deposition of another coat protein species. In any event, it is clear that an additional set of rules needs to be elucidated if we are to fully understand how the spore builds its outer shells. Like the early electron microscopy studies that identified the coat layers and analyses of the coat surface that showed the presence of ridges, the observations of van Ooij et al. uncover yet another layer of regulation of assembly that demands molecular characterization. As a model for macromolecular assembly, the coat is still full of surprises.

Acknowledgments

I thank Jean Greenberg, David Keating, and Maike Müller for helpful suggestions.

Work in my laboratory is supported by grants GM53989 and AI53365 from the NIH.

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson, A. I., and P. Fitz-James. 1976. Structure and morphogenesis of the bacterial spore coat. Bacteriol. Rev. 40:360-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai, K., H. Takamatsu, M. Iwano, T. Kodama, K. Watabe, and N. Ogasawara. 2001. The Bacillus subtilis yabQ gene is essential for formation of the spore cortex. Microbiology 147:919-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagyan, I., and P. Setlow. 2002. Localization of the cortex lytic enzyme CwlJ in spores of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:1219-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behravan, J., H. Chirakkal, A. Masson, and A. Moir. 2000. Mutations in the gerP locus of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus cereus affect access of germinants to their targets in spores. J. Bacteriol. 182:1987-1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley, D. E., and J. G. Franklin. 1958. Electron microscope survey of the surface configuration of spores of the genus Bacillus. J. Bacteriol. 76:618-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabrera-Martinez, R. M., B. Setlow, and P. Setlow. 2002. Studies on the mechanisms of the sporicidal action of ortho- phthalaldehyde. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:675-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chada, V. G., E. A. Sanstad, R. Wang, and A. Driks. 2003. Morphogenesis of Bacillus spore surfaces. J. Bacteriol. 185:6255-6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comas-Riu, J., and J. Vives-Rego. 2002. Cytometric monitoring of growth, sporogenesis and spore cell sorting in Paenibacillus polymyxa (formerly Bacillus polymyxa). J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:475-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driks, A. 1999. The Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driks, A. 2003. The dynamic spore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:3007-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Driks, A. 2002. Proteins of the spore core and coat, p. 527-536. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Driks, A., S. Roels, B. Beall, C. P. J. Moran, and R. Losick. 1994. Subcellular localization of proteins involved in the assembly of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 8:234-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichenberger, P., S. T. Jensen, E. M. Conlon, C. van Ooij, J. Silvaggi, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, M. Fujita, S. Ben-Yehuda, P. Stragier, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2003. The σE regulon and the identification of additional sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 327:945-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enguita, F. J., D. Marcal, L. O. Martins, R. Grenha, A. O. Henriques, P. F. Lindley, and M. A. Carrondo. 2004. Substrate and dioxygen binding to the endospore coat laccase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:23472-23476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enguita, F. J., P. M. Matias, L. O. Martins, D. Placido, A. O. Henriques, and M. A. Carrondo. 2002. Spore-coat laccase CotA from Bacillus subtilis: crystallization and preliminary X-ray characterization by the MAD method. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58:1490-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henriques, A. O., B. W. Beall, K. Roland, and C. P. J. Moran. 1995. Characterization of cotJ, a sigma E-controlled operon affecting the polypeptide composition of the coat of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 177:3394-3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henriques, A. O., and C. P. Moran, Jr. 2000. Structure and assembly of the bacterial endospore coat. Methods 20:95-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt, S. C., and E. R. Leadbetter. 1969. Comparative ultrastructure of selected aerobic spore-forming bacteria: a freeze-etching study. Bacteriol. Rev. 33:346-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hullo, M. F., I. Moszer, A. Danchin, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 2001. CotA of Bacillus subtilis is a copper-dependent laccase. J. Bacteriol. 183:5426-5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isticato, R., G. Cangiano, H. T. Tran, A. Ciabattini, D. Medaglini, M. R. Oggioni, M. De Felice, G. Pozzi, and E. Ricca. 2001. Surface display of recombinant proteins on Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 183:6294-6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch, R. 1876. The etiology of anthrax, based on the life history of Bacillus anthracis. Beitr. Biol. Pflanz. 2:277-310. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornberg, A., J. A. Spudich, D. L. Nelson, and M. Deutscher. 1968. Origin of proteins in sporulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 37:51-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwana, R., Y. Kasahara, M. Fujibayashi, H. Takamatsu, N. Ogasawara, and K. Watabe. 2002. Proteomics characterization of novel spore proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 148:3971-3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai, E.-M., N. D. Phadke, M. T. Kachman, R. Giorno, S. Vazquez, J. A. Vazquez, J. R. Maddock, and A. Driks. 2003. Proteomic analysis of the spore coats of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 185:1443-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loshon, C. A., E. Melly, B. Setlow, and P. Setlow. 2001. Analysis of the killing of spores of Bacillus subtilis by a new disinfectant, Sterilox. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:1051-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins, L. O., C. M. Soares, M. M. Pereira, M. Teixeira, T. Costa, G. H. Jones, and A. O. Henriques. 2002. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a highly stable bacterial laccase that occurs as a structural component of the Bacillus subtilis endospore coat. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18849-18859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauriello, E. M., H. Duc le, R. Isticato, G. Cangiano, H. A. Hong, M. De Felice, E. Ricca, and S. M. Cutting. 2004. Display of heterologous antigens on the Bacillus subtilis spore coat using CotC as a fusion partner. Vaccine 22:1177-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson, W. L., N. Munakata, G. Horneck, H. J. Melosh, and P. Setlow. 2000. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:548-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piggot, P., and R. Losick. 2002. Sporulation genes and intercompartmental regulation, p. 483-517. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 30.Price, K. D., and R. Losick. 1999. A four-dimensional view of assembly of a morphogenetic protein during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:781-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roels, S., A. Driks, and R. Losick. 1992. Characterization of spoIVA, a sporulation gene involved in coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:575-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setlow, P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:550-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shapiro, M. P., B. Setlow, and P. Setlow. 2004. Killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by a modified Fenton reagent containing CuCl2 and ascorbic acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2535-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonenshein, A. L., J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.). 2002. Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 35.Stevens, C. M., R. Daniel, N. Illing, and J. Errington. 1992. Characterization of a sporulation gene, spoIVA, involved in spore coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:586-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takamatsu, H., and K. Watabe. 2002. Assembly and genetics of spore protective structures. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:434-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.van Ooij, C., P. Eichenberger, and R. Losick. 2004. Dynamic patterns of subcellular protein localization during spore coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:4441-4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vreeland, R. H., W. D. Rosenzweig, and D. W. Powers. 2000. Isolation of a 250 million-year-old halotolerant bacterium from a primary salt crystal. Nature 407:897-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warth, A. D., D. F. Ohye, and W. G. Murrell. 1963. The composition and structure of bacterial spores. J. Cell Biol. 16:579-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young, S. B., and P. Setlow. 2004. Mechanisms of killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by Decon and Oxone, two general decontaminants for biological agents. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96:289-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young, S. B., and P. Setlow. 2003. Mechanisms of killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by hypochlorite and chlorine dioxide. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:54-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng, L., W. P. Donovan, P. C. Fitz-James, and R. Losick. 1988. Gene encoding a morphogenic protein required in the assembly of the outer coat of the Bacillus subtilis endospore. Genes Dev. 2:1047-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zilhao, R., M. Serrano, R. Isticato, E. Ricca, C. P. Moran, Jr., and A. O. Henriques. 2004. Interactions among CotB, CotG, and CotH during assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol 186:1110-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]