Abstract

Background

In animal studies, iron deficiency during pregnancy has been linked to increased offspring cardiovascular risk. No previous population studies have measured arterial stiffness early in life to examine its association with maternal iron status.

Objective

This study aimed to examine the association between maternal iron status in early pregnancy with infant brachio-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV).

Methods

The Baby VIP (Baby's Vascular Health and Iron in Pregnancy) study is a UK-based birth cohort which recruited 362 women after delivery from the Leeds Teaching Hospitals postnatal wards. Ferritin and transferrin receptor levels were measured in maternal serum samples previously obtained in the first trimester. Infant brachio-femoral PWV was measured during a home visit at 2–6 weeks.

Results

Iron depletion (ferritin <15 µg/l) was detected in 79 (23%) women in early pregnancy. Infant PWV (mean = 6.7 m/s, SD = 1.3, n = 284) was neither associated with maternal ferritin (adjusted change per 10 µg/l = 0.02, 95% CI: −0.01, 0.1), nor with iron depletion (adjusted change = −0.2, 95% CI: −0.6, 0.2). No evidence of association was observed between maternal serum transferrin receptor level and its ratio to ferritin with infant PWV. Maternal anaemia (<11 g/dl) at <20 weeks’ gestation was associated with a 1.0-m/s increase in infant PWV (adjusted 95% CI: 0.1, 1.9).

Conclusion

This is the largest study to date which has assessed peripheral PWV as a measure of arterial stiffness in infants. There was no evidence of an association between markers of maternal iron status early in pregnancy and infant PWV.

Key Words: Vascular stiffness, Iron, Pregnancy, Infant, Micronutrients, Anaemia

Introduction

Arterial stiffness in adults has been shown to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular events [1], It has also been linked with childhood indicators of cardiovascular risk [2, 3]. Increased arterial stiffness leads to faster return of the reflected pulse wave from peripheral sites to the left ventricle, and hence suboptimal ventricular-arterial interaction [4], Measurement of pulse wave velocity (PWV) is accepted as the most simple, convenient and reproducible method to determine arterial stiffness over the life course [1]. PWV is determined by dividing the distance of the pulse travel between two sites by the transit time, and is inversely related to arterial distensibility [4].

Iron deficiency (ID) is the leading single nutrient deficiency in the world. Maternal ID anaemia has been linked to risk of low birth weight, preterm delivery and infant ID anaemia [5]. There is experimental evidence supporting the involvement of maternal ID in the programming of adult hypertension and obesity. In pregnant rats, ID results in increased risk of offspring obesity and hypertension [6]. Postulated mechanisms include increased placental cytokine and tumour necrosis factor levels, and altered metabolism of mediators of cell function and metals such as copper [7]. ID can also induce changes in placental structure including decreased capillary length and surface area and increased placental vascularisation, and may interfere with fetal kidney development and nephron number [8].

Few studies have examined the relationship between maternal nutritional exposures and childhood arterial stiffness [9, 10, 11]. To our knowledge, there are no population studies assessing such relationships with neonatal or infant arterial stiffness. However, it has been shown that PWV measurements can be reliably ascertained in newborns with good reproducibility [12, 13].

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between maternal iron status early in pregnancy with offspring arterial stiffness at 2–6 weeks of life.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

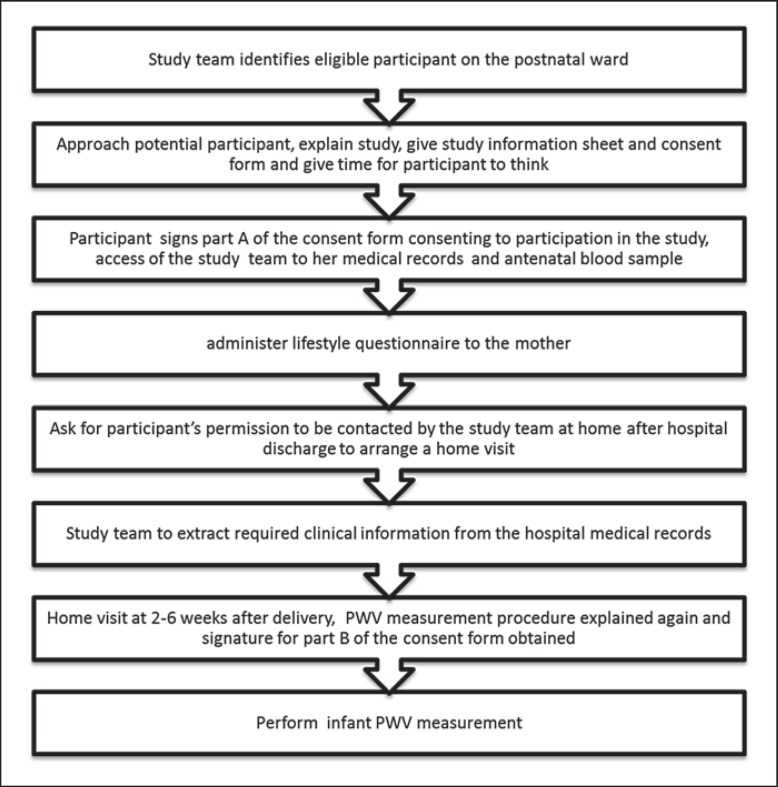

The Baby VIP (Baby's Vascular Health and Iron in Pregnancy) study is a birth cohort study. It comprises women aged ≥18 years who gave birth at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust Maternity Unit at a gestational age of ≥34 weeks between February 2012 and January 2013. The participants were recruited from the postnatal wards after delivery. Those who agreed to take part were asked if the research team could contact them after they were discharged home to arrange a home visit within 6 weeks. Figure 1 illustrates the participant flowchart. Ethical approval was obtained from the South Yorkshire Committee of the NHS National Research Ethics Service (11/YH/0064). All procedures were in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration as revised in 1983.

Fig. 1.

Participant flowchart.

Outcome Measurement

Brachio-femoral PWV (bfPWV) was measured using the Vicorder device (Skidmore Medical), which uses an oscillometric technique. This kit provides a non-invasive method of measuring PWV, and is thought to be relatively independent of operator skills [14]. Two infant-size cuffs were used. The arm cuff was wrapped around the bare skin of the baby's arm, with the mid cuff point halfway between the shoulder and the elbow. The leg cuff was wrapped around the bare skin of the baby's ipsilateral thigh with the mid cuff point halfway between the groin and the knee. Using a tape measure, the distance was measured in centimetres between the two marked points in a straight line while keeping the baby's thigh straight, with the tape kept on the internal side of the arm alongside the trunk. The pressure applied was 35 mm Hg for both the arm and the leg. The pulse recording at the two arterial sites was obtained simultaneously. Transit time was measured as the time delay between the feet of the proximal and the distal pulse waves. A minimum of two PWV readings was obtained from each baby. If they were more than 0.3 m/s different, a third reading was obtained. The average of all available readings for each baby was used in the analyses.

Exposure Measurement

Serum ferritin (sF) is the most widely used biomarker in the assessment of iron status. The ratio of serum transferrin receptor (sTfR) to sF (R/F) is considered the gold standard marker of iron status [15], and has been used to assess iron status in pregnant populations [16]. Maternal serum samples of 348 women, previously stored during the first trimester of pregnancy as part of routine antenatal care, were analysed. sF was measured using ELISA (Demeditic, Kiel, Germany). 10 µl of plasma were treated with a sandwich ELISA method, using fluorometric measurements and calibrated using standards supplied by the manufacturer. Quality controls were included as appropriate. The WHO cutoff of 15 µg/l in sF was used to indicate depleted iron stores [17].

sTfR assays were performed using a commercially available kit based on a polyclonal antibody in a sandwich enzyme immunoassay format (DTFR1; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn., USA). This yielded sTfR levels in nmol/l units. The values were converted to µg/l using a molecular weight of sTfR of 75,000 Da (R&D technical data sheet). The R/F ratio was obtained by dividing sTfR over sF (µg/l:µg/l). This was logged to obtain normal distribution.

Maternal haemoglobin (Hb) values were extracted from the antenatal care records and/or the hospital electronic results server. A cutoff of 11 g/dl in Hb was used to indicate anaemia at ≤20 weeks’ gestation, and 10.5 g/dl to indicate anaemia beyond 20 weeks’ gestation, following the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines [18].

Covariable Assessment

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) was derived using the GeoConvert tool utilising the UK census data (geoconvert.mimas.ac.uk). Birth weight, gestational age, parity, maternal height, weight, ethnicity, smoking, pregnancy complications (pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes), blood pressure measurements and intake of iron supplements were extracted from the clinical records. Infant heart rate was recorded by the Vicorder device with each PWV measurement.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 11 (2009; College Station, Tex., USA). Customised birth weight centile was calculated taking into account gestational age, maternal height, maternal pre-pregnancy or booking weight, ethnicity, parity, and neonatal sex [19]. Univariable analysis was performed using an independent sample t test, one-way analysis of variance or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical variables.

Multiple linear regression was performed with PWV as the main outcome, and indicators of maternal iron status as predictors. The models were adjusted for baby covariables at birth (customised birth weight centile) and at measurement (age, position, measurement side, arousal state and type of feeding), and maternal covariables including age, smoking status, the presence of gestational diabetes or pre-eclampsia, blood pressure at booking and at 36 weeks’ gestation, and IMD deprivation score. Sensitivity analyses were performed taking into account the intake of iron supplements during pregnancy and infant heart rate at the time of PWV measurements.

Sample Size Calculation

For a difference of 0.3 m/s in PWV between iron-deficient and non-iron-deficient mothers, using a mean of 4.7 m/s, a standard deviation (SD) of 0.6 m/s and a prevalence of ID of 20%, a sample size of 265 mother-baby pairs was required to achieve 90% power with p = 0.05 [12],

Results

We recruited 362 mother-baby pairs, with 284 (79%) babies going on to have PWV measurements at home. Mean infant bfPWV was 6.7 m/s (SD = 1.3). The mean difference in PWV between the first and the second measurement was −0.02 m/s (95% CI: −0.16, 0.11, Bland-Altman limits of agreements: −2.3 to 2.2 m/s). The with-in-subject coefficient of variation was 1.3% and the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.6 (95% CI: 0.5–0.7). The difference between the first and second PWV measurement was 0.3 m/s or less in 31% and 0.5 m/s or less in 49% of the babies. Mean baby age at the time of measurement was 25 days (SD = 6). Table 1 describes infant PWV in relation to measurement conditions and baby characteristics. The baby being asleep was, on average, associated with a 0.9-m/s reduction in infant bfPWV (95% CI: 0.5, 1.3). Table 2 describes the characteristics of participants with or without PWV measurements.

Table 1.

Infant bfPWV in relation to measurement conditions and infant characteristics in the Baby VIP study

| Infant bfPWV, m/s |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mean | SD | p | |

| Sleeping status | <0.001a | |||

| Asleep | 48 | 5.9 | 1.1 | |

| Awake | 239 | 6.8 | 1.3 | |

| Position during measurement | <0.001b | |||

| In mother's arms | 121 | 6.5 | 1.3 | |

| Feeding in mother's arms | 101 | 7.2 | 1.2 | |

| In cot/on sofa or floor | 61 | 6.1 | 1.1 | |

| Measurement side | 0.2a | |||

| Right | 98 | 6.8 | 1.4 | |

| Left | 181 | 6.6 | 1.2 | |

| Baby's age | 0.7a | |||

| <28 days | 206 | 6.6 | 1.3 | |

| ≥28 days | 77 | 6.7 | 1.4 | |

| Type of feeding | 0.06b | |||

| Breast | 122 | 6.9 | 1.4 | |

| Bottled | 109 | 6.5 | 1.3 | |

| Mixed | 53 | 6.4 | 1.2 | |

Independent samples t test.

One-way analysis of variance.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants in the Baby VIP study (n = 362) according to whether babies were followed up by home visits to measure PWV after hospital recruitment

| With PWV measurements |

Without PWV measurements |

pa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total n | mean ± SD/n (%)/median | 95% CI/IQR | total n | mean ± SD/n (%)/median | 95% CI/IQR | ||

| Gestational age, days | 284 | 277 ± 14 | 78 | 276.3 ± 14 | 0.5 | ||

| Birth weight, g | 284 | 3,339 ± 636 | 78 | 3,293 ± 621 | 0.6 | ||

| Maternal age at antenatal booking, years | 284 | 31.1 ± 5.5 | 78 | 28.6 ± 6.0 | 0.0007 | ||

| Maternal BMI at antenatal booking | 281 | 26.5 ± 6.1 | 77 | 25.3 ± 4.9 | 0.1 | ||

| IMD | 284 | 28.6 ± 19.1 | 78 | 32.7 ± 19.6 | 0.1 | ||

| Maternal Hb at ≤20 weeks’ gestation, g/dl | 263 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 66 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Maternal Hb at >20 weeks’ gestation, g/dl | 266 | 11.6 ± 1.0 | 71 | 11.4 ± 1.1 | 0.2 | ||

| First-trimester maternal sF, µg/l | 273 | 33.4 | 17.4–61.6 | 75 | 28.6 | 13.1–68.7 | 0.5 |

| First-trimester maternal sTfR, nmol/l | 273 | 13.1 | 10.4–16.1 | 75 | 12.3 | 10.1–16.1 | 0.6 |

| First-trimester maternal R/F ratio, µg/l | 273 | 27.5 | 15.3–61.9 | 75 | 32.0 | 14.0–72.9 | 0.6 |

| Primiparous | 284 | 144 (51) | 45, 57 | 78 | 29 (37) | 27, 49 | 0.03 |

| Male baby | 284 | 137 (48) | 42, 54 | 78 | 45 (58) | 47, 69 | 0.1 |

| Maternal White ethnicity | 284 | 220 (78) | 72, 82 | 78 | 68 (87) | 78, 94 | 0.1 |

| Maternal smoking at antenatal booking | 278 | 36 (13) | 9, 18 | 76 | 13 (17) | 9, 28 | 0.5 |

| Gestational diabetes | 284 | 5 (2) | 1, 4 | 78 | 1 (1) | 0, 7 | 0.1 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 284 | 3 (1.1) | 0,3.1 | 78 | 3 (3.9) | 1.0, 10.8 | 0.1 |

| Anaemia at ≤20 weeks’ gestation (<11 g/dl) | 263 | 10 (4) | 2, 7 | 66 | 6 (9) | 3, 19 | 0.1 |

| Anaemia at >20 weeks’ gestation (<10.5 g/dl) | 266 | 35 (13.2) | 9.3, 1.8 | 71 | 13 (18.3) | 10.1, 29.3 | 0.3 |

| Had taken iron supplements in pregnancy | 284 | 92 (32) | 27, 38 | 77 | 29 (38) | 27, 49 | 0.4 |

| Had taken multivitamin supplements in pregnancy | 284 | 157 (55) | 49, 61 | 77 | 32 (42) | 30, 53 | 0.03 |

Independent samples t test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical variables.

Median sF was 31.7 µg/l [interquartile range (IQR): 16.9–62.4]. 79 women (23%) women had depleted iron stores. The median sTfR was 12.8 nmol/l (IQR: 10.2–16.1). Mean maternal Hb was 12.6 g/dl and 11.6 g/dl (SD = 1.0) in the first and second halves of pregnancy, respectively. The prevalence of anaemia at ≥20 weeks’ (<11 g/dl) and >20 weeks’ gestation (<10.5 g/dl) was 5% (16/329) and 14% (48/337), respectively. Only half of the anaemic women in the first half (n = 8) and 45% of the anaemic women in the second half of pregnancy (n = 22) had a first trimester sF of less than 15 µg/l. 121 women (34%) took iron supplements during pregnancy: 8 (2%) started in the first trimester compared to 67 (19%) in the second and 46 (13%) in the third trimester.

There was no evidence of association between infant bfPWV and maternal sF (adjusted change in PWV in m/s per 10-µg/l change in sF = 0.02, 95% CI: −0.01, 0.1, p = 0.3), nor with maternal iron depletion (adjusted change in PWV in m/s = −0.2, 95% CI: −0.6, 0.2, p = 0.3). No evidence of association was observed between maternal sTfR or log R/F with infant bfPWV. However, anaemic mothers in the first half of pregnancy (Hb <11 g/dl) had infants with higher PWV by 1.0 m/s on average (95% CI: 0.1, 1.8, p = 0.02; table 3).

Table 3.

Associations of infant bfPWV at 2–6 weeks with indicators of iron status during pregnancy in the Baby VIP study

| Predictor | Change in infant bfPWV (m/s) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unadjusted | 95% CI | p | adjusteda | adjusted 95% CI | p | n (multi-variable model) | |

| Maternal sF at 12 weeks’ gestation (per 10-µg/l change) | 0.02 | –0.01, 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.02 | –0.01, 0.1 | 0.3 | 261 |

| Maternal iron depletion at 12 weeks’ gestation (sF <15 µg/l) | –0.2 | –0.5, 0.3 | 0.4 | –0.2 | –0.6, 0.2 | 0.3 | 261 |

| Maternal sTfR at 12 weeks’ gestation (nmol/l) | 0.03 | –0.004, 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | –0.01, 0.04 | 0.3 | 261 |

| Maternal log R/F ratio at 12 weeks’ gestation (µg/l) | 0 | –0.1, 0.1 | 0.9 | 0 | –0.2, 0.1 | 0.5 | 261 |

| Maternal Hb at ≥20 weeks’ gestation (g/dl) | 0.1 | –0.1, 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | –0.1, 0.2 | 0.6 | 253 |

| Maternal Hb at >20 weeks’ gestation (g/dl) | 0.2 | –0.001, 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.2 | –0.004, 0.3 | 0.06 | 256 |

| Maternal anaemia at ≥20 weeks’ gestation (<11 g/dl) | 0.7 | –0.1, 1.6 | 0.08 | 1.0 | 0.1, 1.9 | 0.02 | 253 |

| Maternal anaemia at >20 weeks’ gestation (<10.5 g/dl) | –0.1 | –0.5, 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.01 | –0.5, 0.5 | 0.9 | 256 |

Adjusted for baby's age, PWV measurement circumstances (position, feeding, asleep or awake, side), maternal age, smoking, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, blood pressure at booking and 36 weeks’ gestation, deprivation score, and customised birth weight centile (takes into account maternal pre-pregnancy weight, height, ethnicity, parity, gestational age and baby's sex).

No association was observed between maternal intake of iron supplements at any stage in pregnancy and infant PWV (unadjusted change = −0.1, 95% CI: −0.5, 0.2). Adjusting for iron supplement intake did not alter the results of the models examining the association between maternal iron biomarkers with infant bfPWV, while it strengthened the association between maternal anaemia in early pregnancy and infant PWV (adjusted change = 1.2 m/s, 95% CI: 0.3, 2.1). Adjusting for infant heart rate attenuated the association between early pregnancy maternal anaemia and infant PWV (adjusted change = 0.4 m/s, 95% CI: −0.7, 1.4, p = 0.5).

Discussion

PWV, a potential marker of cardiovascular health later in life, was ascertained in 284 babies aged 2–6 weeks at home in the Baby VIP study. We found no association between maternal iron status biomarkers in early pregnancy and infant PWV. However, maternal anaemia in the first half of pregnancy was associated with increased infant PWV.

The elastic properties of arteries vary along the arterial tree, with more elastic proximal arteries and stiffer distal ones. The amplitude of the pressure wave is higher in peripheral arteries than in central arteries. This ‘amplification phenomenon’ is known to be more pronounced in younger subjects [1]. In adults, average brachio-ankle PWV is approximately 20% higher than carotid-femoral PWV [20]. These reasons may explain the relatively higher bfPWV average in our study compared to the average newborn aortic PWV reported elsewhere [12, 21]. Another explanation could also be the way the distance was assessed between the two arterial sites (in a straight line). This is likely to be shorter than the distance the pulse wave travels along the vessel.

The ability of PWV measured very early in life to predict later cardiovascular health is unknown. Although there was no evidence of association with maternal iron status, this does not exclude the possibility that the latter may be linked to offspring cardiovascular indicators in adulthood. Therefore, long-term follow-up of a birth cohort with information on maternal iron status in pregnancy is required.

We found an association between early pregnancy maternal anaemia and infant arterial stiffness. Anaemia could reflect the extreme of the ID spectrum; however, only half of the anaemic women had sF <15 µg/l. Another study by the authors found no evidence of association between early pregnancy maternal Hb and offspring PWV at 10 years [22]. Maternal anaemia may have a true effect on infant arterial function, which may subside later in life. Alternatively, the observed association could be due to residual confounding by other causes of maternal poor health.

In a sensitivity analysis, we adjusted for infant heart rate in the association between maternal anaemia and infant PWV. This can improve the precision of the estimate if heart rate is strongly linked to the outcome. However, it cannot be considered a true confounder as it cannot affect maternal anaemia. Therefore, it was not included in the main model. Some studies have found heart rate to have a significant effect on arterial stiffness, while others have not [23, 24, 25, 26]. Infant heart rate could potentially be a mediator in the relationship between maternal anaemia and infant PWV if it is postulated that anaemic mothers are more likely to give birth to anaemic babies. However in this study, although infant heart rate was inversely associated with PWV, it was not associated with maternal anaemia (data not shown).

Our study assessed the exposure of interest prospectively, as the maternal serum samples were collected in the first trimester of pregnancy. We used the best available measure for iron status – the R/F ratio which relates directly to total body iron stores [15]. We assessed PWV, an innovative measure of cardiovascular health which causes less distress than measuring blood pressure in neonates/young infants, on a relatively large study population compared to other studies which have assessed PWV in this age group [12, 21]. Information on maternal Hb and iron supplements was ascertained objectively from the medical records, rather than by self-reporting.

A potential source of error in measuring PWV is the use of more distal conduit sites as a surrogate for less accessible central arteries [4]. However, the forearm circulation is where blood pressure is commonly measured, and lower limb arteries are commonly altered by atherosclerosis [1]. Estimating the actual distance between the recording sites using surface measurements could also be a source of error. The shorter the distance, the greater the absolute error in determining transit time [1]. However, our PWV data spread corresponds well with most other studies. Furthermore, any errors in measuring the distance between the arterial sites would be non-differential as the researcher was blind to the exposure. A further limitation is that we did not record infant blood pressure in this study.

This study demonstrates that infant arterial stiffness can be assessed using non-invasive techniques in population studies. Further research is needed to investigate the relationship between maternal nutrition during pregnancy and PWV in the child and adult offspring using a prospective study design to investigate the potential pathways underlying the developmental origins of cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to all study participants. Our thanks go to Angela Wray, Julie Grindey and Viv Dolby for data collection; Antony Hales, Russel Booth, Ruth Owen and Christine Kennedy for facilitating laboratory analysis, and Stephen Greenwald for advice on PWV measurement. Source of funding: N.A.A. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship (WT87789). H.J.M. and H.E.H. are supported by the Scottish Government Rural and Environmental Services (RESAS). N.A.B.S. is supported by Cerebra.

References

- 1.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lm J-A, Lee J-W, Shim J-Y, Lee H-R, Lee D-C. Association between brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyai N, Arita M, Miyashita K, Morioka I, Takeda S. The influence of obesity and metabolic risk variables on brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in healthy adolescents. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:444–450. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung Y-F. Arterial stiffness in the young: assessment, determinants, and implications. Korean Circ J. 2010;40:153–162. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2010.40.4.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholl TO. Iron status during pregnancy: setting the stage for mother and infant. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1218S–1222S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambling L, Dunford S, Wallace D, Zuur G, Solanky N, Kaila S, McArdle H. Iron deficiency during pregnancy affects postnatal blood pressure in the rat. J Physiol. 2003;552:603–610. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.051383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gambling L, Danzeisen R, Fosset C, Andersen HS, Dunford S, Srai SKS, McArdle HJ. Iron and copper interactions in development and the effect on pregnancy outcome. J Nutr. 2003;133:1554S–1556S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1554S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gambling L, McArdle HJ. Iron, copper and fetal development. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:553–562. doi: 10.1079/pns2004385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larnkjaer A, Christensen JH, Michaelsen KF, Lauritzen L. Maternal fish oil supplementation during lactation does not affect blood pressure, pulse wave velocity, or heart rate variability in 2.5-y-old children. J Nutr. 2006;136:1539–1544. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinra S, Sarma K, Ghagoorunissa, Mendu V, Ravikumar R, Mohan V, Wilkinson I, Cockroft J, Davey Smith G, Ben-Shlomo Y. Effect of integration of supplemental nutrition with public health programmes in pregnancy and early childhood on cardiovascular risk in rural Indian adolescents: long term follow-up of Hyderabad nutritional trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morley R, Dwyer T, Hynes KL, Cochrane J, Ponsonby AL, Parkington HC, Carlin JB. Maternal alcohol intake and offspring pulse wave velocity. Neonatology. 2010;97:204–211. doi: 10.1159/000252973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koudsi A, Oldroyd J, McElduff P, Banerjee M, Vyas A, Cruickshank JK. Maternal and neonatal influences on and reproducibility of neonatal aortic pulse wave velocity. Hypertension. 2007;49:225–231. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000250434.73119.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S, Chetty S, Lowenthal A, Evans JM, Vu C, Stauffer KJ, Lyell D, Selamet Tierney ES. Feasibility of neonatal pulse wave velocity and association with maternal hemoglobin A1c. Neonatology. 2014;107:20–26. doi: 10.1159/000366467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Leeuwen-Segarceanu EM, Tromp WF, Bos WJW, Vogels OJM, Groothoff JW, van der Lee JH. Comparison of two instruments measuring carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity: Vicorder versus sphygmocor. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1687. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833a8b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmermann M. Methods to assess iron and iodine status. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:S2–S9. doi: 10.1017/S000711450800679X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mei Z, Cogswell ME, Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Cusick SE, Lacher DA, Grummer-Strawn LM. Assessment of iron status in us pregnant women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999-2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1312–1320. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.007195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serum Ferritin Concentrations for the Assessment of Iron Status and Iron Deficiency in Populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.NICE: Antenatal Care: Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardosi J. Customised fetal growth standards: rationale and clinical application. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28:33–40. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka H, Munakata M, Kawano Y, Ohishi M, Shoji T, Sugawara J, Tomiyama H, Yamashina A, Yasuda H, Sawayama T. Comparison between carotid-femoral and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity as measures of arterial stiffness. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2022–2027. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832e94e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alhashemi H, Colen T, Hirose A, Alrajaa N, Jain V, Savard W, Stickland M, Davidge S, Hornberger L. Exploring the relationship between increased arterial stiffness and myocardial hypertrophy in infants of diabetic mothers. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:S96–S97. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alwan NA, Cade JE, Greenwood DC, Deanfield J, Lawlor DA. Associations of maternal iron intake and hemoglobin in pregnancy with offspring vascular phenotypes and adiposity at age 10: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan I, Butlin M, Liu YY, Ng K, Avolio AP. Heart rate dependence of aortic pulse wave velocity at different arterial pressures in rats. Hypertension. 2012;60:528–533. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albaladejo P, Copie X, Boutouyrie P, Laloux B, Déclère AD, Smulyan H, Bénétos A. Heart rate, arterial stiffness, and wave reflections in paced patients. Hypertension. 2001;38:949–952. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stefanadis C, Dernellis J, Vavuranakis M, Tsiamis E, Vlachopoulos C, Konstantinos Toutouzas, Diamandopoulos L, Pitsavos C, Toutouzas P. Effects of ventricular pacing-induced tachycardia on aortic mechanics in man. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;39:506–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lantelme P, Mestre C, Lievre M, Gressard A, Milon H. Heart rate: an important confounder of pulse wave velocity assessment. Hypertension. 2002;39:1083–1087. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000019132.41066.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]