Abstract

Aim:

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been practiced in India for thousands of years. The aim of this study was to determine the extent of use, perception and attitude of doctors and patients utilizing the same healthcare facility.

Methods:

This study was conducted among 200 doctors working at a tertiary care teaching Hospital, India and 403 patients attending the same, to determine the extent of usage, attitude and perception toward CAM.

Results:

The use of CAM was more among doctors (58%) when compared with the patients (28%). Among doctors, those who had utilized CAM themselves, recommended CAM as a therapy to their patients (52%) and enquired about its use from patients (37%) to a greater extent. CAM was used concomitantly with allopathic medicine by 60% patients. Very few patients (7%) were asked by their doctors about CAM use, and only 19% patients voluntarily informed their doctors about the CAM they were using. Most patients who used CAM felt it to be more effective, safer, less costly and easily available in comparison to allopathic medicines.

Conclusion:

CAM is used commonly by both doctors and patients. There is a lack of communication between doctors and patients regarding CAM, which may be improved by sensitization of doctors and inclusion of CAM in the medical curriculum

KEY WORDS: Attitude, complementary and alternative medicine, doctors and patients, perception

Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been defined as a group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices and products that are presently not considered to be a part of conventional medicine.[1] CAM is being increasingly used by people all over the world.[2,3,4]

In a systematic review of use of CAM in the world, a total of 47 publications were reviewed containing 51 reports from 49 surveys conducted in 15 (out of a possible 196) countries. The surveys indicated that CAM was frequently used and that prevalence estimates varied widely between the 15 countries; the prevalence of all types of CAM use ranged from 9.8% to 76%.[5] There was consistent evidence that adults were more frequent users of CAM than children; and that national estimates of CAM use were highest in East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Malaysia. In developing countries, the World Health Organization reports that approximately 80% of the world populations rely on traditional medicines mainly of herbal sources, in their primary healthcare.[6] Surveys on the use of CAM among doctors have shown variation in physicians’ beliefs and practices with respect to CAM.[7,8,9,10,11] Many doctors view CAM therapies as not part of legitimate medical practice. Although many have a positive attitude towards CAM, they discourage CAM therapies among patients because of their lack of knowledge about the safety and efficacy of CAM treatments.[9,10]

India is the birth place of one of the oldest systems of medicines, Ayurveda, which had its origin around 2000 years back. Ayurveda, Yoga, Siddha and Unani and Homeopathy are recognized in India as the Indian systems of medicines.[11] Despite the recognition by the Government of India and easy availability of CAM including the Indian systems of medicine in India, CAM is still not a part of the conventional medical curriculum in majority of medical colleges in India. As a result the medical graduate may lack awareness about CAM. Although CAM has been practiced in India for thousands of years, there is limited literature available on the extent of use, attitude and perception of patients utilizing CAM services and none among doctors in India. Since practitioners of modern medicines may have to encounter patients using CAM, it would be useful to know their attitude and perception towards CAM.

Hence, we conducted this study to assess the extent of use of CAM among doctors and patients utilizing the same allopathic healthcare facility (a teaching, tertiary care, government hospital) and to examine their perception and attitude towards CAM.

Methods

The study was conducted among 200 doctors of Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, India and 403 patients attending the Outpatient Department of the same hospital. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee and informed consent was obtained from the subjects. The hospital where the study was conducted is a government teaching hospital in North India having a large patient base. Patients both from Delhi and neighboring States attend the hospital's Out Patient's Department (OPD). They include both urban and rural patients. The doctors included in the study were both resident doctors and senior consultants working in the hospital. The same data collector interviewed all the patients and doctors to maintain uniformity of data collection. The instrument for data collection was a pretested, semi-structured, validated questionnaire developed by the researchers and made separately for doctors and patients. The proformas were divided into two parts. The first part included questions regarding the demographic status. The second part had questions pertaining to the perception and attitude towards CAM and its utilization by the study subjects that is, doctors and patients. CAM was defined as all the systems of medicines other than allopathy. These included the Indian systems of medicines Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, Yoga, Homeopathy and others shown in table. The list of CAM utilized in India was provided at the end of the proforma for easy recall. Space was provided for participants to indicate use of other therapies that were not listed.

Doctor Survey

The proforma for physicians had questions about their age, sex, designation, utilization of CAM, type of CAM used, indication of CAM usage, outcome of CAM treatment, whether they recommended CAM to their patients or referred them to CAM practitioners, whether they asked their patients about usage of CAM and the importance CAM sensitization to medical students and fellow practitioners. Questions on the awareness regarding sources of information about herbal medicines, any drug interactions between allopathic and herbal medicines, knowledge about ongoing clinical trials on herbal medicines were also included.

Patient Survey

Patient's demographic section had questions on age, sex, residence, diet (vegetarian and nonvegetarian), any addiction habit (alcohol, smoking, drugs) and religion. Questions in the patient's proforma included the reason for CAM use, how soon CAM was used after onset of illness, whether or not CAM was used with allopathic medicines and any side-effects observed during the use of CAM. Furthermore, the questionnaire ascertained whether they informed their medical practitioner of the CAM they were using. They were also asked about the source of their CAM awareness, who advised use of CAM and their reasons for making such choices.

Statistical Analysis

Results of both doctors and patients were analyzed separately. They were categorized as CAM utilizing and CAM nonutilizing groups. These groups were compared for any difference in demographic variables affecting CAM utilization, using the Chi-square test. The attitude and perception regarding CAM were also compared between CAM utilizing and CAM nonutilizing doctors, using the Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered as significant. The statistical analysis was conducted using Epi-info version 3.3.2.

Results

Demographics

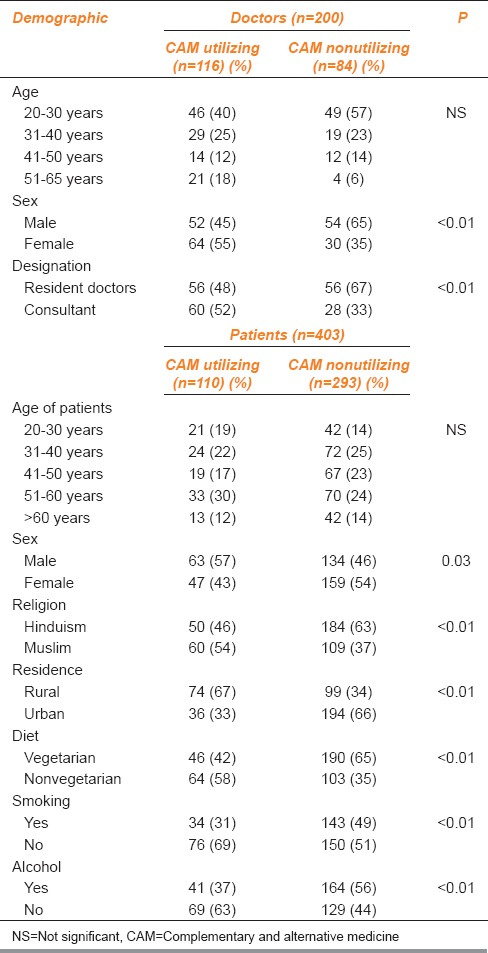

Out of 200 doctors who had been surveyed, 58% (116) utilized CAM therapies. Among the CAM users, majority were female consultants aged more than 50 years. A total of 403 patients participated in the survey and 28% (110) amongst them were utilizing or had utilized CAM. Of them majority were males (57%) and in the age group of 51–60 years (26%). CAM use was significantly more among Muslim patients (54%), patients who had a nonvegetarian diet (58.5%), nonsmokers and teetotalers. The demographic details of doctors and patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The influence of demographic factors on the use of CAM in doctors and patients

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Utilization Patterns

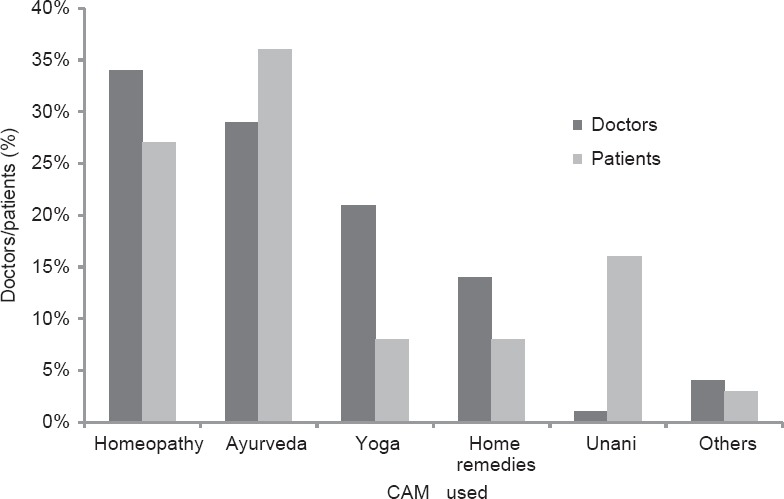

Amongst the doctors Homeopathy (34%) was the most commonly utilized CAM, followed by Ayurveda (29%), Yoga (21%), Home remedies (14%), Unani (1%) and others (4%). With the patients Ayurveda (36%) was the most common CAM used, followed by Homeopathy (27%), Unani (16%), Yoga (8%), Home remedies (8%) and others. The percentage total may exceed 100% as more than one choice was mentioned by the respondents in some cases. A greater percentage of the patients were using the Unani system of medicine than the doctors (16% vs. 1%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Utilization pattern of complementary and alternative medicine among doctors and patients

The indications for using CAM were different with doctors and patients. The most common indications for CAM usage among the doctors were low back ache (32%), arthritis (27%), bronchial asthma (21%), common cold (18%) baldness (16%) and other ailments (5%). The most common reasons for using CAM in patients were fever (38%), skin ailments (28%), constipation (20%), arthritis (16%), gastritis (12%), and other ailments (4%). The percentage total may exceed 100% as more than one indication was mentioned by the respondents. Majority of the patients (51%) used CAM immediately on getting unwell. CAM was used alone by 40% of the patients while 60% of the patients used CAM together with allopathic medicine.

Perception about Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Doctors

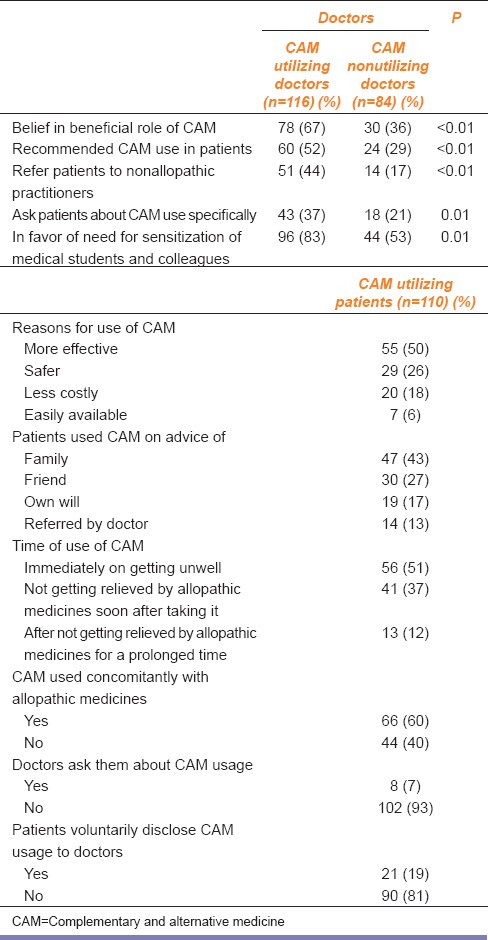

Significant differences were noted between the CAM utilizing doctors and the nonutilizing doctors regarding their attitude and perception toward CAM [Table 2]. Fifty percent of the doctors, who used CAM, felt better after using it. Doctors, who used CAM had a belief in the beneficial role of CAM (67%), recommended CAM as a therapy to patients to a greater extent (52%), referred their patients to CAM practitioners (44%), asked patients about CAM use (37%) and favored sensitization of medical students and fellow colleagues about CAM, more significantly in comparison to doctors who did not use CAM (P < 0.01) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Attitude and perception about CAM amongst doctors and patients

In general, both the groups had low awareness regarding the sources of information about herbal medicines. Only 17% of CAM utilizing doctors and 15% of CAM nonutilizing doctors could correctly name a source of information about herbal medicine. Knowledge about herb-drug interaction between CAM utilizing doctors (11%) and CAM nonutilizing doctors (9%) was also low. Most commonly mentioned herb-drug interactions by doctors were between gingko biloba-anticoagulants, ginger-antiplatelet and garlic-antidiabetic medications. Awareness about ongoing clinical trials of herbal medicines ranged from 3% amongst CAM nonusers to 6% amongst CAM users. The three most commonly mentioned clinical trials of herbal medicines by doctors were effect of garlic on hepatic cirrhosis, effect of turmeric on diabetes and turmeric on mouth ulcer.

Patients

More than half of the patients using CAM were advised by their family (43%) and friends (27%) to try the alternate treatment modality and only 13% were referred by doctors [Table 2]. Most patients used CAM as they perceived it to be more effective (50%) than conventional medicine. The other reasons for using CAM included less expensive and easy availability. Majority of patients (56%) who used CAM felt better after using it. Most of the patients used CAM immediately after getting unwell (51%) and many used it concomitantly with allopathic medicine (60%). The communication between the doctors and patients regarding CAM use was very poor. Most of the patients (93%) had not been asked by their doctors about any alternative therapies during the course of history taking in the OPD. Only 19% CAM utilizing patients voluntarily informed their doctors about the CAM they were using.

Discussion

Although India is the birth place of one of the oldest CAMs in existence, that is, Ayurveda and the Government of India has recognized Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Siddha and Unani and Homeopathy (AYUSH) as Indian systems of Medicine, there are very few published studies documenting the extent of use, attitude and perception towards CAM in the Indian population.[12,13,14] This is the first study documenting findings amongst the practitioners of allopathic medicine working in and the patients utilizing the same healthcare facility.

The overall extent of use of CAM was 38% when the results of doctors and patients were combined. This is lesser to the reported use of CAM from earlier studies in India and other countries.[2,3,4,12,13,14,15,16] A greater proportion of doctors utilized CAM in comparison to patients 58% versus 28%. This may indicate a more positive attitude of doctors toward CAM when compared to the patients. Another study by Furlow et al. 2008 had also found that doctors have a more positive attitude toward CAM as compared to the patients.[7] One of the possible reasons of higher usage and awareness of CAM among doctors could be their higher educational status in comparison to the patients. This finding is similar to another study where the usage CAM was found to be associated with level of education of users.[17] People having low levels of education were less likely to use CAM and the usage increased typically with higher educational levels.[13,14,15,16,17]

There were overall more males as doctors in the survey. But a greater number of female doctors used CAM in proportion to their male counterparts. In previous studies also, it was observed that amongst doctors, female doctors were more likely to believe in CAM than males.[7] Consultants were utilizing CAM more than resident doctors. This may be related to a change in attitude and perception with age and life's experiences. Also disillusionment with conventional medicine may set in with advancing age because of concerns about side-effects, lack of satisfaction and its failure to take a holistic approach.[18] In an earlier reported Indian study, 51% of the study population started CAM therapy following dissatisfaction with allopathic medicine particularly for chronic diseases.[14]

Most of the patients used CAM concomitantly with allopathic medicine as per advice by friends and family. This is similar to an earlier reported study where 78% of patients started CAM therapy on the advice of friends and family.[12] A significant association was found between CAM usage and nonvegetarian diet. Most of the patients who visit the hospital are residents of the adjoining areas where there is a predominance of Muslim population. In these areas there are many traditional healers and practitioners of CAM. This demographic distribution and easy availability of these therapies may account for the larger number of patients of this faith. This is similar to other studies where easy and cheap availability of CAM products were found to be major reasons for their use.[19]

The preferred CAM amongst doctors was Homeopathy followed by Ayurveda. Probably there is greater awareness of Homeopathy as a science and hence acceptability by doctors. Ayurveda is easily available and less costly in comparison to conventional medicine and may thus have been preferred by the patients. This finding is similar to earlier Indian studies where Ayurveda was most commonly used CAM among patients.[12,14] Since a considerable proportion of our patient population were Muslims this may account for the greater use of Unani medicine amongst the patients.

Complementary and alternative medicine was used by doctors mainly for chronic conditions, as has been reported in another study also.[15] Among the patients, CAM was also used for less serious conditions. A study on CAM use in the US showed that one third of the respondents used CAM for nonserious medical conditions.[3] Majority of the patients used CAM concomitantly with allopathic medicine. These results are similar to the study on the Indian population at Chatsworth, South Africa where people were observed to use CAM and allopathic medicine concomitantly.[16]

The patients preferred to use CAM as they perceived it to be better, economical, safer and easily available. Majority of the patients had not been asked by their doctors about any alternative therapies during the course of history taking in the OPD. This could be because of lack of awareness on the doctor's part about CAM. Another reason could be the acute shortage of time for adequate history taking. The hospital gets thousands of patients daily in the OPD and doctors are under tremendous pressure to see and manage them. The voluntary reporting about CAM use from the patient's side to the doctor was also considerably low in this study (19%). Earlier Indian studies reported even lower reporting of CAM usage by patients to their physicians 3.8–13%.[12,14] Our study result also correlates with a UK study published in 2004 where 92% patients did not disclose the use of herbal medicine to their doctors.[20] Possible explanations for poor communication between doctors and patients could be that the doctors themselves do not address this topic and the patients may not think it necessary or be fearful of the doctor's reactions.[21,22] CAM is also perceived as a safe therapy by most people. The self-use of CAM and limited disclosure by the patients of alternative therapies could result in delays in starting conventional treatment, wrong diagnosis and interference with the mechanism of action of a prescribed allopathic medicine.[7] Not asking patients whether they are using any other therapy may also result in drug interactions and unforeseen side effects.[20]

More than half of the doctors used CAM therapies and 67% believed in their beneficial role. Meta-analysis of literature, as well as individual national surveys indicate that there is a significant interest in CAM among doctors from varying sub specialties.[23,24] Although majority of doctors used CAM therapy, only 44% referred patients for CAM. These observations are similar to those observed in a random sample of doctors in California who demonstrated an overall positive attitude towards CAM but 61% found themselves discouraging CAM therapies to their patients.[9] Similarly at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester a survey revealed that although most of the doctors agreed that CAM therapies held promise for the treatment of disease, most were not comfortable in counseling patients about CAM treatment.[25] Lack of knowledge of sources of information about CAM specifically herbal medicine was observed, as only 15% of doctors using CAM were aware of a source of information about herbal medicine.

A possible reason for this could be that the doctors feel they don’t have sufficient knowledge to suggest use of CAM to their patients. Although their awareness about CAM may permit them to use CAM for their own personal problems. Lack of knowledge among doctors has been a well cited reason in many studies for not to use or recommend CAM to patients.[8,9,25]

Majority of doctors recommended that CAM should be incorporated into the medical undergraduate curriculum. This is similar to other studies where doctors felt that evidence based CAM should be part of medical curriculum.[26] It is important that CAM be taught in medical colleges to sensitize and increase awareness about CAM, both efficacy and safety. This is especially important for India, as the Government is Opening more Health Centers for Indian systems of medicine, in many cases in the same health facility as the allopathic center to promote for a holistic health care approach. Hence, the need for sensitization of medical students to other systems of medicine is extremely urgent. Teaching of integrative medicine in the curriculum may be a way to bring about the changes.[27,28]

The need to introduce CAM sensitization in medical profession education has been recognized in the United States of America and Europe. Sixty-four percent of US medical schools and 73% of US Pharmacy schools offer CAM courses as part of their curriculum.[29] In Europe 40% of medical departments and 72% of health sciences departments offer CAM related courses.[30] Sensitization of medical graduates to CAM would enable them to understand the principles and basis of alternative medical therapies, their advantages and disadvantages. This will also enable them to think that there may be other therapeutic options available for patients outside their own science. This may benefit the patient in the long run. Sensitization of medical graduates to CAM does not imply that they would prescribe CAM therapies, only that they would be in a better position to understand the CAM therapies the patients are using, refer the patients to CAM and look for possible drug interactions. In addition, since CAM is already being practiced and used, other issues regarding regulations in quality control and prescribing of alternative systems of medicine by practitioners of other systems (allopathy by AYUSH practitioners and CAM by allopathy practitioners) need to be established. This is to ensure patient safety, as all systems of medicine whether allopathy or CAM, have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Limitations of the Study

We used different questionnaires for doctors and patients. Many questions were asked specifically to doctors or patients, this was because we were not comparing differences in attitudes between doctors and patients. Our aim was to assess extent of use, attitude and perception of both doctors and patients.

Conclusions

Complementary and alternative medicine is being used commonly both by doctors and patients and often concomitantly with allopathic medicines. There is inadequate doctor-patient communication about concomitant usage of CAM with allopathic medicine. Revision in medical curriculum is urgently needed to incorporate sensitization of medical graduates toward CAM so as to enable them to better understand the implications of the use of CAM by their patients. This will also help in optimization of holistic healthcare in the country.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the help given by Dr. Pooja Chatley in preparation of the protocol and Dr. Nitin Kaushik and Anshul Gupta for collecting data. Dr. Jugal Kishore provided us with statistical assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health. What is complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)? [Last cited on 2009 Aug 03]. Available from: http://www.nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/

- 2.Fisher P, Ward A. Complementary medicine in Europe. BMJ. 1994;309:107–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6947.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. Prevalence and cost of alternative medicine in Australia. Lancet. 1996;347:569–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: A systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:924–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan K. Some aspects of toxic contaminants in herbal medicines. Chemosphere. 2003;52:1361–71. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furlow ML, Patel DA, Sen A, Liu JR. Physician and patient attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine in obstetrics and gynecology. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milden SP, Stokols D. Physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding complementary and alternative medicine. Behav Med. 2004;30:73–82. doi: 10.3200/BMED.30.2.73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahner-Roedler DL, Vincent A, Elkin PL, Loehrer LL, Cha SS, Bauer BA. Physicians’ attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine and their knowledge of specific therapies: A survey at an academic medical center. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3:495–501. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer BA. Herbal therapy: What a clinician needs to know to counsel patients effectively. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:835–41. doi: 10.4065/75.8.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. [Last cited on 2009 Aug 09]. Available from: http://www.indianmedicine.nic.in/

- 12.Zaman T, Agarwal S, Handa R. Complementary and alternative medicine use in rheumatoid arthritis: An audit of patients visiting a tertiary care centre. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar D, Bajaj S, Mehrotra R. Knowledge, attitude and practice of complementary and alternative medicines for diabetes. Public Health. 2006;120:705–11. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta M, Shafiq N, Kumari S, Pandhi P. Patterns and perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among leukaemia patients visiting haematology clinic of a north Indian tertiary care hospital. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:671–6. doi: 10.1002/pds.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewith GT, Hyland M, Gray SF. Attitudes to and use of complementary medicine among physicians in the United Kingdom. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:167–72. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh V, Raidoo DM, Harries CS. The prevalence, patterns of usage and people's attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among the Indian community in Chatsworth, South Africa. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997-2002. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11:42–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dilhuydy JM. Patients’ attraction to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): A reality which physicians can neither ignore nor deny. Bull Cancer. 2003;90:623–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith L, Ernst E, Ewings P, Myers P, Smith C. Co-ingestion of herbal medicines and warfarin. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:439–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuzzolin L, Zaffani S, Murgia V, Gangemi M, Meneghelli G, Chiamenti G, et al. Patterns and perceptions of complementary/alternative medicine among paediatricians and patients’ mothers: A review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:820–7. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickers KA, Jolly KB, Greenfield SM. Herbal medicine: Women's views, knowledge and interaction with doctors: A qualitative study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:40. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: A review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fountain-Polley S, Kawai G, Goldstein A, Ninan T. Knowledge and exposure to complementary and alternative medicine in paediatric doctors: A questionnaire survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Astin JA, Marie A, Pelletier KR, Hansen E, Haskell WL. A review of the incorporation of complementary and alternative medicine by mainstream physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2303–10. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.21.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jump J, Yarbrough L, Kilpatrick S, Cable T. Physicians’ attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine-expanding medical horizons. A report to the National Institutes of Health on alternative medical systems and practices in the United States (NIH Publication 94-066) Integr Med. 1998;1:149–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghassemi J. Finding the evidence in CAM: A student's perspective. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:395–7. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owen DK, Lewith G, Stephens CR. Can doctors respond to patients’ increasing interest in complementary and alternative medicine? BMJ. 2001;322:154–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7279.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutta AP, Daftary MN, Egba PA, Kang H. State of CAM education in U.S. schools of pharmacy: Results of a national survey. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2003;43:81–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varga O, Márton S, Molnár P. Status of complementary and alternative medicine in European medical schools. Forsch Komplementmed. 2006;13:41–5. doi: 10.1159/000090216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]