Abstract

Objective:

Till date, several studies have compared angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in terms of delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy. But the superiority of one drug class over the other remains unsettled. This study has retrospectively compared the effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in diabetic nephropathy. The study aims to compare ACE inhibitors and ARBs in terms of delaying or preventing the progression of diabetic nephropathy, association between blood pressure (B.P) and urinary albumin and also B.P and serum creatinine with ACE inhibitor and ARB, know the percentage of hyperkalemia in patients of diabetic nephropathy receiving ACE inhibitor or ARB.

Settings and Design:

A total of 134 patients diagnosed with diabetic nephropathy during the years 2001–2010 and having a complete follow-up were studied, out of which 99 were on ARB (63 patients of Losartan and 36 of Telmisartan) and 35 on ACE inhibitor (Ramipril).

Subjects and Methods:

There was at least 1-month of interval between each observation made and also between the date of treatment started and the first reading that is, the observation of the 1st month. In total, three readings were taken that is, of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd month after the treatment started. Comparison of the 1st and 3rd month after the treatment started was done. Mean ± standard deviation, Paired t-test, and Chi-square were used for the analysis of the data.

Results:

The results reflect that ARBs (Losartan and Telmisartan) when compared to ACE inhibitor (Ramipril) are more effective in terms of delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy and also in providing renoprotection. Also, ARBs have the property of simultaneously decreasing the systolic B.P and albuminuria when compared to ACE inhibitor (Ramipril).

Conclusions:

Angiotensin receptor blockers are more renoprotective than ACE inhibitors and also provide better cardioprotection.

KEY WORDS: Angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, diabetes, diabetic nephropathy

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy or nephropatia diabetica is a progressive kidney disease caused by angiopathy of the capillaries in the renal glomeruli. It is characterized by nephrotic syndrome and diffuse glomerulosclerosis. It is also known as Kimmelstiel–Wilson syndrome or nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis or intercapillary glomerulonephritis. It is due to longstanding diabetes mellitus however not all persons with diabetes develop this condition.

Diabetic nephropathy characterized by persistent albuminuria is the single leading cause of end-stage renal disease. In the last few years, a number of intermediations using renin-angiotensin blocking drugs have been demonstrated to slow the progression of renal disease. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are currently recommended by clinical guidelines for the treatment of albuminuria in diabetic nephropathy. In patients with type 1diabetes, hypertension and any degree of albuminuria ACE inhibitors delay the progression of nephropathy,[1] whereas in majority of the cases of the patients of type 2 diabetes, hypertension and renal insufficiency (defined as serum creatinine above 1.5 mg/dl) only ARBs delay the progression of nephropathy. There are no formal comparisons or substantial differences available between ACE inhibitors and ARBs to establish a superiority of one drug class over the other in terms of renal protection. In addition, the quantity of head to head comparisons is insufficient to draw a firm conclusion. Hence, this study attempts to compare the effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs retrospectively.

Objectives

The main objectives of this study was to compare ACE inhibitors and ARBs in terms of delaying or preventing the progression of diabetic nephropathy, to know the association between blood pressure (B.P) and urinary albumin and also between B.P and serum creatinine with ACE inhibitor and ARB, to know the percentage of hyperkalemia in patients of diabetic nephropathy after taking ACE inhibitor or ARB.

Subjects and Methods

Design and Methods

This was a retrospective study, and the sample was collected from Gujarat Kidney Foundation, Ahmedabad, which consisted of 134 patients of diabetic nephropathy. The collected data consisted of patients diagnosed with diabetic nephropathy during the years 2001–2010 with complete follow-up. Out of 134 patients, 99 patients were on ARBs (Losartan and Telmisartan) and 35 patients were on ACE inhibitor (Ramipril). A criterion for the selection of the patients of diabetic nephropathy was the diagnosis made by the doctor and then reported in the case papers of the patient. There was at least 1-month of interval between each observation made and also between the date of treatment started and the first reading that is, the observation of the 1st month. In total, three readings were taken that is, of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd month after the treatment started. Readings of the parameters such as B.P, urinary albumin, serum creatinine and serum potassium were taken into consideration.

The patients included in the study were known cases of hypertension and diabetic nephropathy and having a follow-up of 3 months or more. The patients were >18 years of age and a B.P >140/90 mm Hg (JNC-VII classification is taken as a reference), taking either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB or taking drugs in which ACE inhibitors or ARBs were combined with some other molecules.

Those patients taking both ACE inhibitor and ARB,[2] who were <18 years of age with a B.P <140/90 mm Hg were excluded from the study.

Results are described as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The central limit theorem states that if the sample size is >50, all distributions tend to be normal. Paired t-test has been used to compare the differences in the mean albumin levels as well as in the mean serum creatinine levels between the 1st and the 3rd month after the treatment started and a P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The Chi-square test has been applied to test whether there is a significant association of urinary albumin, as well as serum creatinine with B.P.

Results

At the start of the treatment, the mean age was 59.97 ± 12.62 and out of 134 patients, 54 patients were female and 80 patients were male.

For the analysis of the data, B.P was classified according to JNC-VII report on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high B.P (JNC-VII).[3]

Also, urinary albumin, serum creatinine, and serum potassium levels, which were used for the analysis, were classified.

All the patients considered for the study had albuminuria and it was graded in the patients report as: Grade 0 was considered nil, grade 1 as mild, grade 2 as moderate, grade 3 as heavy, grade 4 as severe. Macroalbuminuria as such is defined as a urinary albumin excretion of >300 mg/24 h.[4]

Serum creatinine levels up to 1.6 mg/dl in men and 1.4 mg/dl in female was considered normal.[5]

Analysis of the data also required categorizing serum potassium levels. A range of 3.5–5.0 mEq/L was considered normal while levels between 2.5 and 3.5 were considered as mild hypokalemia and <2.5 was considered as severe hypokalemia. On the other hand, levels more between 5.0 and 6.5 mEq/L was considered as hyperkalemia, levels >6.5 mEq/L was considered as severe hyperkalemia.

One of the main objectives of the study is to compare ACE inhibitors and ARBs in terms of delaying or preventing the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Progression of diabetic nephropathy can be well judged by the urinary albumin levels.[6] Hence, when mean ± SD as well as Paired t-test was used for the same, the results obtained were as follows.

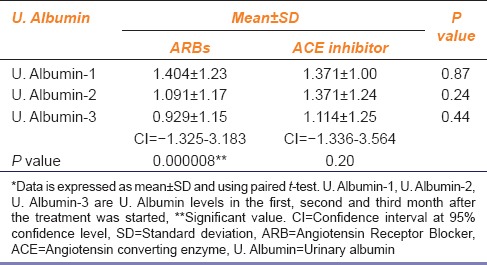

It is evident from the Table 1 that, there is a considerable difference in the values of mean ± SD of the urinary albumin readings of the 1st and the 3rd month after starting ARB. While, on the other hand, the difference of the same in the ACE inhibitor group is quite less. Also, when Paired t-test was used, the only reading that came significant (P = 0.000008 as P < 0.05 was considered significant) was that obtained from the 1st and 3rd month observations of urinary albumin after taking ARB. Also, the confidence interval at 95% confidence level for ARB in the 3rd month after the treatment started was −1.325 to 3.183 which was narrower than the confidence interval (−1.336 to 3.564) for ACE inhibitor indicating a higher variation in case of ACE inhibitors. This suggests that ARBs more effectively reduced albuminuria as compared to ACE inhibitors.

Table 1.

U. Albumin levels with either ACE inhibitor or ARB

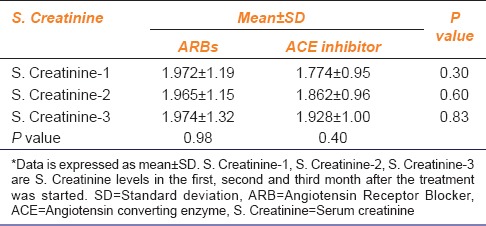

Besides albuminuria, the levels of serum creatinine are suggestive of renal function.[5,7] When mean ± SD values of the levels of serum creatinine in the 1st and 3rd month after starting ACE inhibitor or ARB were considered, an increase in the values was observed in the 3rd month compared to 1st month in ACE inhibitor group, whereas the values of mean ± SD of the 1st and 3rd month data of serum creatinine levels did not change in the ARB group [Table 2]. This means that ACE inhibitor actually increased the serum creatinine levels while on the other hand ARBs stabilized the same.

Table 2.

S. Creatinine levels after starting ACE inhibitor or ARB

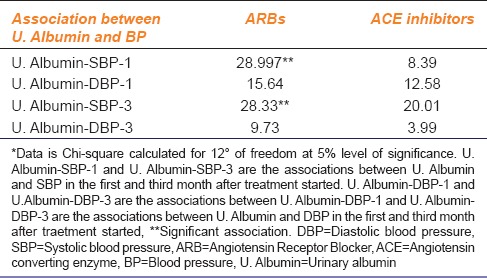

Several studies have reported that there is a strong association between B.P mainly systolic B.P and albuminuria[6] and similarly between B.P mainly systolic and serum creatinine levels.[5] Also, there is evidence that ACE inhibitors reduce albuminuria independent of B.P lowering while ARBs tend to lower both B.P and albuminuria. To test this property of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, Chi-square test was used in this study. When B.P and albuminuria were cross-tabulated according to the JNC-VII and albuminuria classification then, the association between systolic B.P and urinary albumin only under the ARB group was significant that is, 28.997 and 28.33 (critical value 21.026 at 12° of freedom) [Table 3]. For the analysis, only the readings of the 1st and 3rd month after starting the treatment were considered.

Table 3.

U. Albumin and BP in patients who received ARBs and ACE inhibitors

Table 3 also reflects that the results of Chi-square are not significant (critical value 21.026 at 12° of freedom) in the ACE inhibitor group. This means that ACE inhibitors may reduce albuminuria independent of B.P lowering. In the ARB group, the association between the systolic B.P and urinary albumin was significant, that is, 28.997 and 28.33 (critical value 21.026 at 12° of freedom). But, on the other hand, the results for the association between urinary albumin and diastolic pressure were not significant, that is, 15.64 and 9.73 (critical value 21.026 at 12° of freedom). This implies that ARBs reduce albuminuria along with systolic B.P lowering but not with diastolic B.P lowering.

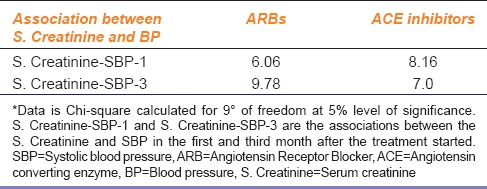

Similarly, Chi-square was used to test whether ACE inhibitors or ARBs affect both serum creatinine levels and B.P simultaneously or not. The results obtained can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

S. Creatinine and BP in patients receiving ARBs and ACE inhibitors

None of the results were significant (critical value 16.919 at 9° of freedom). Hence ARBs or ACE inhibitors do not have an effect on the B.P and serum creatinine levels simultaneously. This means that these two factors work independent of each other, and any change in one factor does not have any effect on the other factor.

Hyperkalemia is major side effect of the patients taking either ACE inhibitor or ARB. The potassium levels need to be closely monitored when the patient is on ACE inhibitor or ARB otherwise it can lead to serious complications. When serum potassium levels were evaluated, it was found that 21.2% of the patients started on ARB had hyperkalemia in the 1st month of treatment that raised to 25.3% in the 3rd month. On the other hand, 25.7% of the patients on ACE inhibitor had hyperkalemia in the 1st month of treatment which increased to 42.9% in the 3rd month. This clearly shows that patients taking ACE inhibitor are more prone to develop hyperkalemia as a side effect and their potassium levels need to be closely monitored.

Discussion

Till date, several studies have compared ACE inhibitors and ARBs in terms of delaying or preventing the progression of diabetic nephropathy. However, the superiority of one drug class over the other remains unsettled.

There is overwhelming evidence from the controlled clinical trials that ACE inhibitors are more beneficial when used in type 1 diabetic patients[1] and ARBs in type 2 diabetic patients.[8,9,10] But this outcome also remains unresolved. Several studies have demonstrated that ARBs are effective in the prevention of renal injury.[11,12] For the treatment of early nephropathy in hypertension, The American Diabetes Association recommends both ACE inhibitors and ARBs to delay the progression of microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria and overt nephropathy.[13] However, in the Microalbuminuria, Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation, Ramipril reduced the risk of developing overt proteinuria from microalbuminuria by 24% compared with placebo.[10]

In this study, results imply that ARBs are more effective in delaying the progression of proteinuria and in turn, diabetic nephropathy. There is a considerable difference in the values of mean ± SD of the urinary albumin readings of the 1st and the 3rd month after starting ARB [Table 1]. While, on the other hand, the difference of the same in the ACE inhibitor group is quite less. Here, the results of the 1st and 3rd month are considered because the results are more specific and clear. Also when Paired t-test was used, the only reading that came significant (P = 0.000008 as P < 0.05 is considered significant) was that obtained from the 1st and 3rd month observations of urinary albumin after taking ARB. Also, the confidence interval at 95% confidence level for ARB in the 3rd month after the treatment started was −1.325 to 3.183, which was narrower than the confidence interval (−1.336 to 3.654) for ACE inhibitor indicating a higher variation in case of ACE inhibitor. This clearly suggests that ARBs more effectively reduce albuminuria in patients of diabetic nephropathy with hypertension.

Also, the levels of serum creatinine are an indicator of renal function.[7] Some studies suggest that ARBs and ACE inhibitors do not reduce the risk of doubling of serum creatinine and slowing the decline in GFR when compared with other antihypertensive agents.[14] But some studies have also shown that ARBs as well as ACE inhibitors tend to reduce the risk of doubling of serum creatinine levels.[15,16]

In this study, the results concerning the levels of serum creatinine in relation to ARBs or ACE inhibitors are a combination of the above two statements. The mean ± SD values of the 1st and the 3rd month data after starting ARB do no change [Table 2]. On the contrary, the mean ± SD values of the 1st and 3rd month data of serum creatinine levels after starting ACE inhibitors noticeably increases. This suggests that ACE inhibitors cause an increase in the serum creatinine levels while ARBs stabilize the same thus, improving the renal function and delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy.

Apart from albumin and creatinine levels, B.P also plays an important role in delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Brenner postulated a causal relationship between the glomerular hypertension occurring at the beginning of the disease and glomerular damage in diabetic nephropathy[6,17,18] and this was then confirmed by a number of studies. A number of clinical trials suggest that when antihypertensives ARBs and ACE inhibitors are used there is an added renoprotective effect beyond their action on B.P. Also, there is evidence that ACE inhibitors reduce albuminuria independent of B.P lowering. In a meta-analysis regression of 100 studies, Kasiske et al. found that ACE inhibitors reduced the level of proteinuria and slowed the rate of decline in renal function regardless of changes in B.P.[19] On the other hand, ARBs reduce albuminuria along with a reduction in B.P. But this simultaneous effect on the B.P is more on the systolic B.P. Also, systolic B.P is more important than diastolic B.P according to the seventh report of the JNC on prevention, detection evaluation and treatment of high B.P.[3]

In this study, when B.P and albuminuria were cross-tabulated according to the JNC-VII and albuminuria classification and Chi-square test was used, the association between systolic B.P and urinary albumin under the ARB group was significant that is, 28.997 and 28.33 (critical value 21.026 at 12° of freedom). For the analysis, only the readings of the 1st and 3rd month after starting the treatment were considered. This result reflects that ARBs reduce mainly systolic B.P along with a reduction in albuminuria. There is no significant effect of ARBs on diastolic B.P in association with albuminuria. Also from the Table 3, it can be seen that the results of Chi-square are not significant (critical value 21.026 at 12° of freedom) in the ACE inhibitor group. This means that ACE inhibitors reduce albuminuria independent of B.P lowering.

Similarly, serum creatinine levels and B.P were cross-tabulated and Chi-square was used to know whether there is any association between the two variables or not. But the results as indicated in Table 4 are insignificant meaning that there was no association between B.P and serum creatinine levels.

There are several adverse effects associated with ACE inhibitors and ARBs. One of the major side effects associated with both these classes of drugs is hyperkalemia. The increase in serum potassium levels can occur due to both the classes of the drugs. But some researchers believe that the incidence of hyperkalemia in patients taking ARBs is less as that compared to ACE inhibitors. The result of this study concerning the serum potassium levels also supports the above belief because on analysis of data the rise in the incidence of hyperkalemia was much more among the patients taking ACE inhibitor.

Conclusion

The results reflect that ARBs (Losartan and Telmisartan) when compared to ACE inhibitor (Ramipril) are more effective in terms of delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy and also in providing renoprotection. Also, ARBs have the property of simultaneously decreasing the systolic B.P and albuminuria when compared to ACE inhibitor (Ramipril) which is equally cardioprotective when compared to ARBs but ACE inhibitor (Ramipril) do not simultaneously decrease the progression of diabetic nephropathy at the same rate as when compared to ARBs (Losartan and telmisartan), thus ARBs proving more effective in cases of diabetic nephropathy with hypertension.

Acknowledgment

Our sincere gratitude to Dr. Niraj Pandit Professors, Department of Community Medicine, Sumandeep Vidyapeeth, for helping us in the statistical analysis of this project.

This research would not have seen the light of the day, had it not been for two eminent doctors of Gujarat Kidney foundation- Dr. Sonal Dalal and Dr. Himanshu Patel who whole-heartedly permitted us to collect data for our research. Our gratitude to them is immense.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD The Collaborative Study Group. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1456–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Ontarget Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–46. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basi S, Fesler P, Mimran A, Lewis JB. Microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes and hypertension: A marker, treatment target, or innocent bystander? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S194–201. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coresh J, Wei GL, McQuillan G, Brancati FL, Levey AS, Jones C, et al. Prevalence of high blood pressure and elevated serum creatinine level in the United States: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988-1994) Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1207–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luño J, Garcia de Vinuesa S, Gomez-Campdera F, Lorenzo I, Valderrábano F. Effects of antihypertensive therapy on progression of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;68:S112–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Levey AS. Serum creatinine as marker of kidney function in South Asians: A study of reduced GFR in adults in Pakistan. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1413–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P Irbesartan in Patients with Type Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:870–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravid M, Brosh D, Levi Z, Bar-Dayan Y, Ravid D, Rachmani R. Use of enalapril to attenuate decline in renal function in normotensive, normoalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:982–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_part_1-199806150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: Results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Lancet. 2000;355:253–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Albarrán O, Gómez O, Ruiz E, Vieitez P, García-Robles R. Role of systolic blood pressureon the progression of kidney damage in an experimental model of type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension (Zucker rats) Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:979–85. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossing P, Parving HH, de Zeeuw D. Renoprotection by blocking the RAAS in diabetic nephropathy – fact or fiction? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2354–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molitch ME, DeFronzo RA, Franz MJ, Keane WF, Mogensen CE, Parving HH, et al. Diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S94–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casas JP, Chua W, Loukogeorgakis S, Vallance P, Smeeth L, Hingorani AD, et al. Effect of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005;366:2026–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia) Lancet. 1997;349:1857–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenner BM. Hemodynamically mediated glomerular injury and the progressive nature of kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1983;23:647–55. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hostetter TH, Troy JL, Brenner BM. Glomerular hemodynamics in experimental diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 1981;19:410–5. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasiske BL, Kalil RS, Ma JZ, Liao M, Keane WF. Effect of antihypertensive therapy on the kidney in patients with diabetes: A meta-regression analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:129–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]