Abstract

Introduction

User engagement in mental health service design is heralded as integral to health systems quality and performance, but does engagement improve health outcomes? This article describes the CORE study protocol, a novel stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial (SWCRCT) to improve psychosocial recovery outcomes for people with severe mental illness.

Methods

An SWCRCT with a nested process evaluation will be conducted over nearly 4 years in Victoria, Australia. 11 teams from four mental health service providers will be randomly allocated to one of three dates 9 months apart to start the intervention. The intervention, a modified version of Mental Health Experience Co-Design (MH ECO), will be delivered to 30 service users, 30 carers and 10 staff in each cluster. Outcome data will be collected at baseline (6 months) and at completion of each intervention wave. The primary outcome is improvement in recovery score using the 24-item Revised Recovery Assessment Scale for service users. Secondary outcomes are improvements to user and carer mental health and well-being using the shortened 8-item version of the WHOQOL Quality of Life scale (EUROHIS), changes to staff attitudes using the 19-item Staff Attitudes to Recovery Scale and recovery orientation of services using the 36-item Recovery Self Assessment Scale (provider version). Intervention and usual care periods will be compared using a linear mixed effects model for continuous outcomes and a generalised linear mixed effects model for binary outcomes. Participants will be analysed in the group that the cluster was assigned to at each time point.

Ethics and dissemination

The University of Melbourne, Human Research Ethics Committee (1340299.3) and the Federal and State Departments of Health Committees (Project 20/2014) granted ethics approval. Baseline data results will be reported in 2015 and outcomes data in 2017.

Trial registration number

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12614000457640.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PSYCHIATRY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to implement a stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial design to identify if an Experience Based Co-Design (EBCD) intervention designed to change recovery orientation of services improves psychosocial recovery outcomes in people with serious mental illnesses.

With the stepped wedge design, all clusters will ultimately receive the intervention while those waiting for the intervention to commence act as controls.

Data will be collected from a cohort of service users from the community mental health setting about recovery experience and intervention effects over time.

System changes due to a major reform of service delivery models may impact on staff continuity and users’ perceptions of service experiences, which may affect outcomes and participation.

The stepped wedge design means that some clusters wait for a long period before starting the intervention, which may increase dropout rates and decrease motivation for participation.

The study cannot include people who do not speak English well due to translation, lack of appropriate culturally specific recovery measures and resource constraints.

Introduction

Background and rationale

User participation in mental health planning and service design is recognised as an important component of system improvements aligned with user needs and patient-centred care. In the published literature, the terms service users, patients, clients and consumers are used interchangeably to refer to recipients of healthcare services, while the term carer/s refers to family or friends; the term ‘user’ is applied in this article as an umbrella term for these related concepts. User participation has expanded beyond surveying people to gather feedback about services to now include meaningful partnerships facilitated through co-learning, active collaboration, shared power and decision-making in healthcare, all of which are encapsulated in the term ‘engagement’.1 2 Engagement has come to be seen as an integral element to improve quality of care experiences and Experience Based Co-Design (EBCD) has emerged as fitting for this task.

EBCD utilises participatory action research methods and is informed by design thinking to identify users’ positive and negative experiences of services.3 4 Design thinking centres on the principles of good design: the functionality (fit for purpose performance); the safety (good engineering and reliability) and the usability (the interaction with the aesthetics) of a system or service.3 EBCD is premised on developing deep understanding of how users perceive and experience the look, feel, processes and structures of services, all the aspects of organisations that users interact with. These interaction points are termed ‘touch points’. This is followed by a process of sharing commonly identified touch points with staff and users, and through a participatory action method bringing everyone together to co-design solutions, especially around the negative touch points. This is followed by the implementation of the changes, a phase called co-design.3 5 6

EBCD extends the current healthcare system focus on design of procedures and structured practices to the design of services based on human experience.5 Engaging users in co-designing organisational changes premised on their experiences is said to result in better quality of care and system performance; this is achieved through illuminating individual's subjective and personal feelings at different points in the care pathway, which in turn is said to result in improvements to health outcomes.7 At present, though, there is little evidence from completed EBCD studies as to whether better quality of care, system performance and improved user experience do result in changes to individual health outcomes.8–10 To date, no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted of EBCD to determine this or explore its potential as a method for building user-designed recovery-oriented mental health systems.

EBCD evidence at present is largely from qualitative evaluations of quality of care improvement initiatives in Alzheimer's and breast and lung cancer care in Australia, New Zealand (NZ) and the UK.11–14 Recently, an accelerated form of EBCD was tested in intensive care and lung cancer services in the UK.15–17 EBCD was implemented in Australian New South Wales (NSW) hospital emergency departments in response to quality and safety issues. Qualitative evaluation of the NSW programme suggested improved patient/user experiences and staff work practices.18–20 There is a current co-design initiative underway in a Victorian Hospital Emergency Department in Australia.21 In the mental health setting, however, EBCD appears only to have been implemented in local, staff-driven quality improvement initiatives in the inpatient setting. These local initiatives indicate good results; for example, complaints were said to be reduced by 80% over 14 months, and staff attitudes to how patients experience services changed.22 Rigorous evaluation of the appropriateness and effectiveness of EBCD in the mental health setting for improving user experience with a focus on improving recovery outcomes has yet to be conducted.

Other methods of user involvement in the community mental health setting have been tested in RCTs, but they have not been co-design or service improvement focused.23–32 In mental health, there is an emphasis on system improvement which is recovery-oriented and coupled with the delivery of evidence-based mental health services. This focus is articulated in policies from the UK,33 34 Canada,35 the USA,36 Australia37–42 and NZ.43 Yet, clearly articulating the components of recovery-oriented service and how these result in health outcomes is difficult. Part of this challenge is linked with how recovery is contemporarily described. There is recognition that user-defined recovery is different from symptom reduction and functional improvements characteristic of earlier concepts of clinical recovery.44 Recovery is articulated as an ongoing, subjective process unique to each individual which encompasses social, psychological, cultural and spiritual dimensions.45 EBCD with its focus on capturing individuals’ subjective experiences of services may then offer a method to facilitate changes in mental health services that are premised on user-driven perspectives of recovery-oriented services.46–48 Determining if this betterment of experience then translates to improved psychosocial recovery outcomes is critical for informing system design and evidence-based mental healthcare. The CORE study will be a world first stepped wedge cluster RCT to test if an EBCD method improves psychosocial recovery outcomes for people affected by mental illness in the community mental health setting.49–51

This article describes the CORE study protocol. The protocol adheres to the SPIRIT 2013 guidelines.52 Guidelines for the development and reporting of stepped wedge designs are currently in formation and not due for release until 2017.53 Planning for the CORE study began in June 2013, services were recruited in early 2014 and recruitment of users and carers was initiated later in 2014. Data collection of outcome measures will be completed in 2017. The study was funded during June 2013 to June 2017.

Objectives

Our hypothesis is that an EBCD intervention aimed at making community mental health services recovery-orientated will result in improved psychosocial recovery outcomes for people affected by mental illness. In addition, it is hypothesised that this will improve carers’ mental health and well-being, and change staff attitudes to recovery and the recovery orientation of services.

Methods

Design

The CORE study is a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial with a nested process evaluation. The nested process evaluation will be explained in a separate publication. A cluster randomised design was selected because the EBCD intervention (explained later) is an organisational/service level intervention which requires a high proportion of staff, users and carers in community mental health services to participate in all the elements; therefore, it was not possible to randomise individuals within a cluster to the different starting dates for the EDCB intervention.54 The stepped wedge design overcomes the logistical constraint of not being able to deliver the intervention concurrently to all clusters. Using a stepped wedge design also enables all participating clusters to ultimately receive the EBCD intervention, which is an advantage when working with a vulnerable population group where it is not ethical to withhold an intervention that is perceived to be beneficial.54–56 Other designs such as a parallel cluster randomised trial were not feasible because sufficient study power could not be achieved to detect the desired effect size with the proposed number of clusters. It was not possible to increase the number of clusters because of practical, cost and logistical constraints.

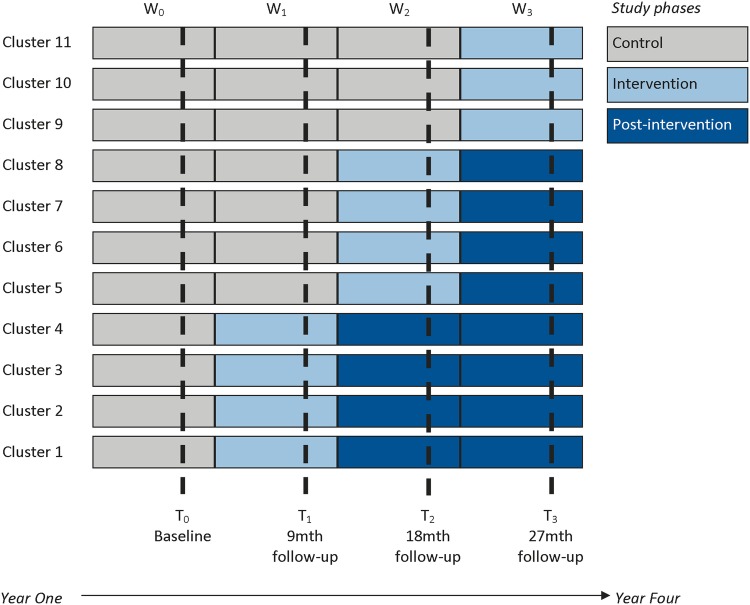

The CORE trial will take almost 4 years to complete. The EBCD intervention will be delivered in three waves to 11 clusters (teams) from four community mental health services in Victoria, Australia, as shown in figure 1. Recruitment of individuals and baseline data collection will occur in wave 0. When baseline data are collected, four teams will be randomly allocated to start the intervention at the beginning of wave 1, four in wave 2 and three in wave 3. The clusters not in receipt of the intervention at each wave act as a control.55 56 Data will be collected at the cluster and individual level at four time points: baseline (6 months) and at the end of the three waves following the completion of the EBCD intervention (see figure 1). The duration of each wave will be 9 months, 7 months for the delivery and implementation of the EBCD intervention and 2 months to collect the follow-up data.

Figure 1.

A stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial in the community mental health setting.

Soon after recruitment of individuals was initiated and study research staff met with service teams on site, there were a few practical and feasibility issues identified that led to the following modifications to the study protocol. These modifications were made before randomly allocating the clusters to the three waves.

At the beginning, recruitment of users and carers was slow; thus, the time frame for recruitment of participants and baseline measurement was extended from an originally proposed 3–6 months to ensure that we reach our target sample size.

The intervention has been modified, so that the information gathering stage takes 12 weeks instead of 20 weeks as per the original protocol (the justifications for this are explained in the intervention section).

In the original proposal, we proposed randomising six clusters from three mental health service providers. Some clusters were formed by combining teams that serviced the same geographical catchment areas to avoid contamination and to ensure that a sufficient number of users were available in each cluster for recruitment. However, after visiting the teams on site, we identified teams that were located some 20–100 km apart but were functioning as discrete teams. This raised a logistical issue around the feasibility of delivering the intervention in vast geographical areas. In particular, widely dispersed service users and carers would be unlikely to actually attend face-to-face meetings linked with the intervention. Thus, the three providers that consisted of two geographically diverse service teams (clusters) were split to form three clusters. Thus, the number of clusters increased from six to nine, that is, three for each service provider.

In addition, to allow for dropout of clusters, we recruited a fourth community mental health service provider with two service teams to supplement the existing three community mental health service providers. During the recruitment process of individuals, it became apparent that there was a risk that some teams may drop out of the study, particularly those that were struggling to identify and recruit sufficient individuals to meet sample size targets.

The remainder of the protocol has been updated to reflect the modifications made to the stepped wedge design where the number of clusters was increased from 6 to 11 and the recruitment period was extended from 3 to 6 months.

Accounting for service user characteristics in the design

The service user groups at community mental health services are characterised as having enduring psychosocial disabilities and long-term impairments from mental illnesses. Conditions range from bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis, chronic depression and anxiety to obsessive compulsive disorders and other personality disorders. The fluctuating nature of mental illnesses means that the majority of service users are likely to be in contact with service teams for long periods of time and this will result in CORE participants being present as service users at multiple follow-up time points. However, it is also anticipated that some users may recover and be discharged from services as they no longer meet the eligibility criteria to receive services or they move away from the area or join a new service.

To address the issue of mobility of users in and out of the services and attrition over the study duration, the CORE study will consist of overlapping samples of individuals that may be measured at one or more subsequent waves.57 58 Individuals (users, carers or staff) will be sampled from each cluster and followed up at each time point (cohort design). Individuals will also be recruited at the beginning of subsequent waves and followed up to refresh the sample and offset attrition over time, particularly as the study is of nearly 4 years duration.57 59

In using the cohort design for individuals, selection bias may be minimised because individuals are recruited prior to randomisation and we can gather richer information than cross-sectional samples. However, a cohort design may introduce bias if there is differential loss to follow-up at each wave and across clusters. Service users may move in and out of the community mental health teams (cluster), and may even move to other teams (who may or may not be enrolled in the trial). Furthermore, with a cohort design, there is a chance that individuals may not attend the mental health service after the intervention has been implemented, hence potentially diluting the intervention effect.

Owing to practical difficulties and high costs, it will not be possible to recruit successive cross-sectional samples of individuals for this study. One reason is that the population is extremely difficult to reach. The recruitment of the individuals requires a combination of dedicated research assistants visiting the Mental Health Community Support Services (MHCSS) to directly offer information and face-to-face recruitment for individuals. In addition, recruitment is dependent on staff in the team clusters generating awareness about the study by giving service users a purposefully designed study postcard. Both methods are costly and time-consuming. Given that the size of the 11 teams (clusters) may range between 60 and 350 service users, there is also a higher chance that individuals are more likely to be sampled more than once, particularly in the smaller clusters if repeated cross-sectional sampling is adopted.

Engagement model underpinning trial design

Informing the trial design is a model of engagement and translation based on the combination of a knowledge transfer model and relational ethical theories. The model has the ultimate goal of building knowledge and shared understanding of the research question, maintaining partnerships and relationships and preparing sites for trial implementation through translation of research systems and structures into practice.60 In addition, such a model incorporates some of the strategies that have been identified as important in addressing mobility issues in trials.58 Engagement activities will include study posters being distributed to access points in local communities near to mental health services, regular scheduled phone calls to key contacts within teams to provide study updates, meetings with service provider organisations to document the policy and service delivery context, conversations with staff about recruitment strategies for users to increase reach and participation in all clusters, a purposefully designed study blog with fortnightly updates to keep staff engaged, newsletters to user and carer participants three times a year and implementation and maintenances strategies for the intervention with staff.61

Study setting and target population

MHCSS providers are located in metropolitan, outer metropolitan and regional areas across Victoria, Australia. In 2010–2011, it was estimated that some 14 000 people in Victoria received services from mental health community support agencies.62 Since the government implemented a new model of delivery, there are now 14 main providers of services in distinct geographical catchments that cross over 2–3 and up to 7 local municipal boundaries. It is well documented that people experiencing mental illness and their carers are difficult to recruit and to retain in research studies.63–68 With this in mind and the aim of CORE to optimise recovery orientation, the study began with the recruitment of the mental health service provider organisations in early 2014 before identifying clusters (teams) within these for participation (explained in the recruitment section).

The primary focus of MHCSS is to provide daily living, social and community support to people living with mental illnesses. Data from 2010 indicated that most people who receive services have between one and four complex factors which include: social isolation, activities of daily living, issues related to unresolved trauma, treatment-resistant symptoms, extensive time to maintain levels of functionality with little improvement in functionality over time, chronic physical health problems, difficulty complying with medications, problems with intellectual disability/cognition, alcohol use, illicit drug use.62 MHCSS provides support across these complex areas; however, staff do not provide clinical assessments and clinical care to individuals.

Services are delivered by community health centres and secular and non-secular non-government community organisations. Services are staffed by a mix of professionals with training in community nursing, social work, occupational therapy and case work. Teams vary in size but typically include 8–15 members (part-time or full-time equivalent) who deliver case management and outreach services to anywhere from 60 to 350 service users in a specified geographical catchment area. The model of service delivery is based on the completion of a comprehensive assessment of service user and carer/family needs (housing, social or other support needs). This assessment forms the basis of a user-directed recovery plan which covers an individual's daily living skills, physical health, housing, relationships, social connections, education, training and employment and parenting or family needs. Carers may be involved in the development of a recovery plan where appropriate.62

Eligibility for receiving services is set out by the Victorian State government in Australia, the funding body authority responsible for MHCSS. These criteria include the age group of 16–65 years, disability attributable to a psychiatric condition (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis, major depression, severe anxiety, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress), impairment that is permanent and results in substantially reduced psychosocial functioning for communication, social interaction, learning, self-care, self-management and impairment that affects the ability for social and economic participation.62

Participant eligibility criteria

Eligible participants for the study are service users receiving care from the participating MHCSS teams including carers of those service users and staff members of those teams. Carers are defined as family members or other persons identified as being in a caring relationship with a person experiencing serious mental illness. To be eligible to participate, all service users and carers will need to understand spoken English as there is limited funding for translation of materials or provision of interpreters including the issue of measures not being validated in languages other than English. Levels of understanding of the requirements for research participation will be determined by the completion of a two-stage consent process. Testing and retesting for understanding is recommended in the literature discussing the issues of informed consent for people with mental illness (explained further in the recruitment section).69

Intervention

The intervention to be delivered is a modified version of Mental Health Experience Based Co-design (MH ECO). MH ECO implements a complex research methodology that applies the theory and practice of EBCD in the mental health setting.49 MH ECO was developed by the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council (VMIAC) and TANDEM representing Victorian mental health carers (formerly the Victorian Mental Health Carers Network) and piloted in former Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation Support Services (now called MHCSS).

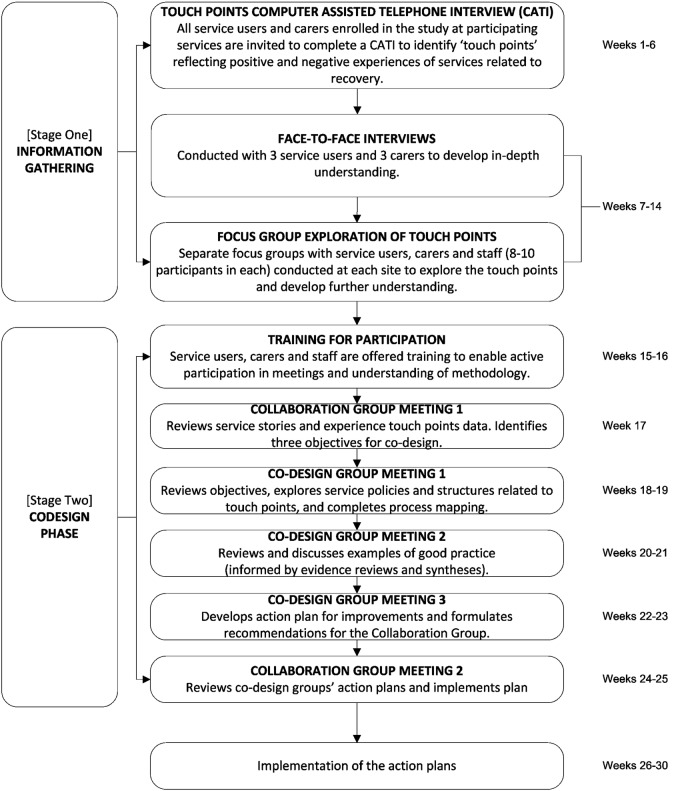

The evaluation of the pilot of MH ECO with young people and adults experiencing serious mental illness indicated positive benefits for staff, users and carers.70 Figure 2 shows the two stages to MH ECO: the information gathering (12 weeks) and the co-design (14 weeks) as modified for delivery in the CORE trial. All 30 users and 30 carers will be invited to participate in all elements of the intervention, but it is not compulsory that everyone participate in every component. The main modification in MH ECO for CORE was shortening the length of the intervention to 26 weeks instead of the original 40 weeks in the earlier MH ECO work (this is explained below). Online supplementary appendix 1 details the programme logic and anticipated outcomes from the intervention.

Figure 2.

Modified Mental Health Experience Co-Design (MH ECO) intervention for the CORE trial.

Stage 1: information gathering

Information gathering is about developing an understanding of how users experience services and identifying the positive and negative touch points for co-design. In MH ECO, this is achieved by all recruited users and carers, who are in the clusters allocated to the intervention wave, being invited to complete a 30 min Computer Assisted Telephone Interview about service experiences; this is called the Touch Points CATI (TP-CATI). The TP-CATI occurs in weeks 1–6 and is comprised of a mix of closed and open ended questions (no more than 20 in total). The closed question responses will be counted to determine the top three positive and top three negatively shared experiences and open-ended responses will be analysed by two members of the investigator team reading responses and identifying the common themes to emerge.

The touch points will be explored further in face-to-face interviews with three users and three carers (1–2 h in length) from each cluster. Interview data will be used to compile service stories which will be used in focus groups held separately with 8–10 staff, 8–10 users and 8–10 carers (up to 2 h in length) in each cluster to explore the touch points in more depth. Sampling for the interviews and the focus groups will take account of gender and illnesses represented to ensure that a wide range of views are collected. The interviews and focus groups occur during weeks 7–14.

Modifications of the information gathering phase of MH ECO for CORE

For CORE, the TP-CATI has been modified from the original telephone interview conducted in the MH ECO pilot from 40 questions that took participants between 45 min and 1.5 h to 20 that will take 30 min. Information gathering will be shortened from a 5-month to 3-month phase for two reasons. First, the sample will already be recruited and users and carers will be expecting contact from the study to complete the service experience questions. Second, international trends within the published literature indicate the importance of accelerated forms of EBCD, so that change issues can be identified and solutions can be co-designed and implemented more efficiently.15 This is an important consideration in the context of people with serious mental illness and their carers where motivation to stay in the intervention may be impacted on by a lengthy intervention phase.

Another modification from the MH ECO pilot is that trained research assistants working from the CATI room facilities at The University of Melbourne will administer the TP-CATI with users and carers rather than an external telephone consulting company. The TP-CATI responses will be entered verbatim into a purpose-built data management system for analysis. Focus groups and interviews will be scheduled by University research staff and facilitated by co-investigators from VMIAC and TANDEM (WW and RC) including two additionally trained intervention facilitators. Interviews and focus groups will be audio recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription company ready for analysis.

Stage 2: co-design phase

The co-design phase will be led by RC and WW with additionally trained facilitators. Facilitation will always include one lead facilitator accompanied by a newly trained facilitator. The facilitators will use techniques from the design sciences to facilitate the co-development of solutions. These techniques include journey mapping through storyboarding and co-designed solutions using prototype development.

Co-design starts with the establishment of a collaboration (one group) and co-design group/s (up to three if three clear touch points are identified). Prior to these groups meeting, the lead facilitators (RC and WW) deliver two 1-day training sessions to staff, service users and carers to resource and support participation in groups and to outline what to expect from participation in group processes; training occurs during weeks 15–16. This is followed by the first meeting of the collaboration group (weeks 17–18) and then subsequent co-design group meetings (weeks 19–24). The collaboration group will meet again in weeks 25–26 to review and implement action plans.

The collaboration and co-design group membership will be different. Collaboration group membership will ideally comprise of eight people in total (one senior manager, one quality manager, two consumers, two carers and two staff members from service teams) and will meet two times (2 h per meeting). The primary role of the collaboration group is to set out some preliminary objectives for co-design groups and to implement the action plan from the co-design group/s.

Each co-design group will ideally comprise of six people (one service manager, two consumers, two carers and one service team member). They meet three times (2 h per meeting): meeting 1 is a review of existing service processes and the identification of areas for improvement related to the touch point in question; meeting 2 is a review of good practice examples and discussion of ideas for action plans; meeting 3 is the development and finalisation of an action plan for implementation to address the touch point. Good practice examples offered in meeting 2 will be informed by evidence reviews completed by the University research team.

Modifications to the MH ECO co-design stage

In the original MH ECO model, a third collaboration group meeting was held 12 weeks later as a monitoring meeting to review the barriers and facilitators to action plan implementation. The CORE study will not include a third collaboration group due to the time constraints and need to complete follow-up measures. In addition, the existing nested process evaluation is designed to capture information about emerging barriers and facilitators to change implementation.

Fidelity checklists for ensuring all elements of the co-design processes have been created for WW and RC to complete, plus an external research evaluator (independent of the intervention) will cross-check these against audio files of sessions to check for fidelity. Independent observations of a random selection of the intervention components (focus groups, interviews, collaboration and co-design groups) across clusters and waves have been scheduled as part of the nested process evaluation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is improvement in psychosocial recovery for individuals measured within 9 months from the beginning of each intervention wave. To determine the most acceptable measures for service users, a small pilot of three potential primary outcome measures was completed with 40 people identified through a consumer organisation supporting people with mental illness. Service users completed combinations of either the 24-item Recovery Assessment Scale Revised (RAS-R)71–73 and the 26-item Maryland Assessment of Recovery in People With Serious Mental Illness (MARS)74 (17 people in total), or the RAS-R and person in recovery version of the 36-item Recovery Self Assessment Scale (RSA)75 (13 people in total). Measures were completed in written form for one group and over the telephone for another to ensure that both completion modes were acceptable and feasible. The pilot identified the 24-item RAS-R as easy to understand and quick to answer; the average completion time was 13–18 min, and it was feasible for written or telephone administration.76 RAS-R was also determined to be a good measure because it has been used in mental health outpatient settings and in peer-run programmes and is one of the few measures available that has been developed from user descriptions of the recovery process.45 It has been validated in an Australian population of people with severe mental illness.72

RAS-R uses a five-point rating scale from 1=‘Strongly Disagree’ to 5=‘Strongly Agree’. Responses can be calculated as a total score ranging from 24 to 120 with higher scores indicating greater recovery. The RAS-R has five domains related to recovery: (1) personal confidence and hope (9 items; range 9–45), (2) willingness to ask for help (3 items; range 3–15), (3) goal and success orientation (5 items; 5–25), (4) reliance on others (4 items; range 4–20) and (5) no domination by symptoms (3 items; range 3–15). A higher rating within each domain indicates recovery progress. At present, there are limited data available on what a clinically significant change is from scales such as RAS-R. Our pilot data indicated that the mean for total RAS-R scores from 17 service users of this measure was 88 (SD=13; range 58–104), which followed a similar pattern to baseline data reported in clinical trials that have used this measure; this has been taken into account in the sample size calculations.25

Secondary outcomes are changes to service users and carers’ mental health and well-being and changes to staff attitudes to recovery and recovery orientation of services. User and carer mental health and well-being will be assessed using the EUROHIS-QOL Eight-Item Index derived from the WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life scale.71 77 78 The index is composed of eight items which cover overall quality of life, general health, energy, daily life activities, esteem, relationships, finances and home.77 78 Each item has a five-point Likert scale and the overall quality of life is calculated by summing the eight items, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Staff attitudes to recovery and recovery orientation in services will be measured using the Staff Attitudes to Recovery Scale (STARS) 19-item questionnaire79 and the provider version of the 36-item RSA.75 Higher scores on the STARS and RSA scales indicate improved staff attitudes to recovery and greater recovery orientation of the mental health services, respectively.

Participant timeline

Sample size

Thirty individuals from nine clusters at each of the four waves (one for baseline and at each follow-up time)will be sufficient to detect an effect size of 0.35 of 1 SD for psychosocial recovery measured at nine monthly intervals between the intervention and usual care waves with at least 80% power (table 2). Sample size was based on the primary outcome of psychosocial recovery score with the following assumptions: intracluster correlation for the outcome of 0.1 and significance of α 5% for a two-sided test, probability that each individual will remain at the site at each wave (0, 0.2 and 0.6) and within-participant correlation of individuals that contributed to at least two consecutive waves (0.2 and 0.7). The sample size was further inflated by including an additional two clusters from a fourth service to allow for loss of clusters (teams) over the duration of the study.

Table 2.

Power calculations to detect an effect size=0.35 of 1 SD between the intervention and usual care periods, assuming an intracluster correlation of 0.1 and alpha of 5% for a two-sided test for a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial with nine clusters and three steps

| Probability of remaining at the centre | Within-participant correlation | Sample cluster size | Power* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NA | 30 | 0.81 |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 30 | 0.82 |

| 0.2 | 0.7 | 30 | 0.86 |

| 0.6 | 0.2 | 30 | 0.86 |

| 0.6 | 0.7 | 30 | 0.94 |

*Power calculations based on 2000 simulations.

NA, not available.

At the time of determining the sample size, there was no sample size formula available for stepped wedge design with longitudinal follow-up of individuals.80 Thus, to determine the power for this study, a simulation study was conducted using a linear mixed effects model where treatment and time effects were assumed as fixed and individual and site effects as random. Whether individuals remained in the cluster at each wave was sampled from a binomial distribution with parameter p, the probability that an individual remained. When p=0, this is equivalent to having an independent sample of participants at each wave (ie, repeated cross-sectional samples). The study power was calculated as the proportion among all 2000 simulation runs of two-sided p values for the estimated fixed treatment effect that reached a nominal value of less than 0.05. Two thousand replications for each set of parameter combinations were sufficient to estimate the power with a margin of error of 1.75%, assuming that the true power was 80%. The simulations were run using R V.3.1.2.81

Table 2 shows that given a fixed sample cluster size, power was the smallest when it was assumed that samples at each time point were independent (ie, probability of remaining at the next wave was zero) and the study power increased as the probability of remaining at the site and within-cluster participant correlation increased.80 Note that the power calculations using the simulation study provided more conservative estimates of the power than the sample size calculations based on the formula provided by Hussey and Hughes.82 These differences may be due to different derivations of the estimated test statistic.

Recruitment

The MHCSS providers

Service providers were identified in early 2014 according to the geographical catchment area they serviced to aim for a spread across metropolitan, outer metropolitan and regional locations. Originally, seven providers were approached by the principal investigator (VJP). One hour face-to-face meetings were held with chief executive officers or senior managers to present the study and its aims. Four of the seven providers invited to the study declined to participate. Reasons included existing research demands, changes to staff, dealing with the implementation of a new model of service delivery at the service and user level and inability to provide a mail-out option for recruitment to service users. The remaining three agreed to take part with the view that clusters would be selected to participate in the intervention at a later date and staff would opt in to the co-design intervention via an online survey. To accommodate for the potential loss of any clusters during the trial, a fourth service provider was approached in December 2014 and agreed to participate. The same approach to recruitment of the service provider was used with a face-to-face meeting to explain the study purpose and aims. Two clusters were added from this service to allow for cluster dropout in the trial.

User and carer recruitment

The user and carer recruitment strategy will include an awareness raising phase where purposefully designed posters and postcards will be placed at participating sites and access points in the local community for 4 weeks prior to a service level mail-out. Artwork for the posters and postcards has been designed by users of art support groups for people living with mental illnesses purposefully selected from a regional area not participating in the study. Poster content is purely to generate awareness about the study while postcard content includes information about the two available models of participation: by telephone or attending a face-to-face study information and recruitment day. As a way of increasing reach and to identify if recruitment rates increase, the study has incorporated face-to-face study information days.83 These information days (referred to as study days herein) are based on a peer support worker (PSW) model combined with trained research assistants, so that PSWs are available to provide information, support and de-briefing to users, while RAs complete the enrolment and baseline survey. The study days include the provision of lunch and a short comedy routine delivered by WISE Stand Up for Mental Health trained performers (a recovery based programme teaching comedy to people with mental illnesses) to disrupt conventional notions of research as tedious and monotonous and demonstrate a recovery practice by people from the same community.84 The aim is to increase reach and, if successful, provide face-to-face study days to complete follow-up measures to retain participants given issues of retention with people living with serious mental illness in research studies.68 At the end of 4 weeks, invitation kits will be mailed out to service users and carers from participating clusters.

Enrolment and informed consent

Enrolment of participants will be completed by research assistants trained in working with people with mental illness and their carers using the purpose designed database. Enrolment processes for users and carers will include entering participant contact details, carer information where available, and completion of the consent process by agreeing or disagreeing with 10 statements read out by research assistant interviewers. The 10 statements will explain study requirements, as well as privacy and ethical obligations of the research team. This will be followed by a second stage consent process (explained earlier) which asks participants to answer three true/false statements to demonstrate their understanding of the nature and requirements of the research. These include: understanding that the study is about recovery and is not for treatment; understanding that being in the study will involve all staff, users and carers working together for the service improvement project (the intervention), understanding that participation is voluntary and that information is kept private. Users who are unable to provide information consent or who are unwell during times of telephone interview and/or face-to-face study day meetings will be placed on a wait list and reinvited to the study in a fortnight to ensure maximum participation options. Staff will be eligible to participate if they work within a participating MHCSS team. Staff consent to participation during face-to-face meetings and via the online staff survey.

Allocation and blinding

Eleven teams (clusters) from four services will be randomly allocated to three starting dates for the intervention (waves); four teams will be allocated to the first two waves and three teams to the last wave. The allocation sequence, stratified by a service provider, will be generated in Stata V.13.085 by a statistician blinded to the identity of the clusters and not involved in the assessment or intervention delivery (PC). The clusters (teams) and order in which they receive the intervention will be communicated to the trial coordinator (KG). The four clusters allocated to the first wave will be notified of intervention commencement after the initial baseline period is completed. The remaining clusters will be notified of their intervention commencement at the start of their allocated wave.

Thus, study participants and research staff will be blinded to the random allocation sequence during baseline recruitment and data collection. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it will not be possible to blind staff, service users and carers to the study arm status at each wave when the clusters have been allocated to the intervention arm. However, participants in the control arm at wave 1 will be blinded to whether they will receive the intervention at the second or third wave. Research interviewers collecting outcome data will remain blinded to who is in receipt of the intervention during the entire study period.

Data collection

Table 1 outlines the data collected at each time point for service users, carers and staff. Data collection in waves 1–3 will occur between the end of the intervention implementation and prior to the start date of the next intervention wave as depicted earlier in figure 1.

Table 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments

| Time points | Wave 0 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 months | 7–15 months | 16–24 months | 25–33 months | |

| Enrolment | ||||

| Eligibility screen | X | |||

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Baseline | X | |||

| Allocation | X | |||

| Study phase | ||||

| Clusters 9–11 | Control | Control | Control | Intervention |

| Clusters 5–8 | Control | Control | Intervention | Postintervention |

| Clusters 1–4 | Control | Intervention | Postintervention | Postintervention |

| Assessment | ||||

| Service users | ||||

| Demographics and clinical details | X | X | X | X |

| Recovery Assessment Scale Revised (RAS-R)71 | X | X | X | X |

| EUROHIS-QOL77 78 | X | X | X | X |

| Carers | ||||

| Demographics | X | X | X | X |

| Demographic and clinical details about the person they care for | X | X | X | X |

| EUROHIS-QOL77 78 | X | X | X | X |

| Staff | ||||

| Demographic and employment details | X | X | X | X |

| Recovery Self Assessment (RSA)75 | X | X | X | X |

| Staff Attitudes to Recovery Scale (STARS)79 | X | X | X | X |

| Data from external sources | ||||

| Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) data* | X | X | X | X |

| Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) data* | X | X | X | X |

| Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD)† | X | X | X | X |

| Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset (VAED)† | X | X | X | X |

| Victorian Mental Health Triage Dataset (using CMI/ODS information system)† | X | X | X | X |

*MBS and PBS information is routinely collection data from the Federal Government in Australia. MBS data provide information about when a medical service was received, the type of service, distance travelled to get to a service and how much out-of-pocket expenses were incurred for services. PBS data provide information on the type of medications prescribed, when they were prescribed, when they were collected, the distance travelled to collect medications and the costs of medications.

†State government emergency (VEMD) and admitted episodes (VAED) data sets provide information about when, where or how an individual was injured or became unwell, how urgent care needs were, the type of care that was received in hospital and length of time in the hospital, how people were cared for once discharged, place of residence, whether the person had a carer, if health insurance was used in hospital, background information about languages spoken and where someone was born. The State government mental health triage data set provides information on where an individual accessed a mental health service, who referred them and why, how urgent the care was and the type of care that was received, place of residence at the time and background information about the languages someone may speak.

The enrolment and baseline survey has been tested with 10 users of mental health services and takes on average 30 min to complete by telephone or face to face. Services users and carers will be able to complete surveys by telephone or face to face; both modes of completion were provided as a way to offer maximum and flexible participation options to people and both the RAS-R and EUROHIS scales have been previously administered in both modes in research studies.76 78 The database allocates a code to participants to conceal personal information when data are aggregated and analysed.

Demographic questions will be completed by users and carers at each data collection time point; they are completed by a research assistant and directly entered into the purpose-built database. Information will include age, gender, education, employment and sources of income. Service users will be asked if they have ever been given a name for their condition, length of time experiencing this condition, who gave them the name for the condition, visits to hospitals and why they access the mental health support service. The research team purposefully included the wording ‘name’ of a condition rather than a diagnosis to identify the ways that users and carers describe the mental health conditions. Carers will be asked how long they have cared for the person and if the mental health support service they are connected with has ever made contact and engaged them in service planning or care planning. Staff, service users and carers will all be asked the Family and Friend Test (FFT) single question to measure quality of service experience.86

Consent will also be sought from service users to access routinely collected government data about health services visits (Medicare Benefits Scheme), medication prescriptions (Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme), emergency department (Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset) and hospital visits (Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset), distance travelled to access services and obtain medication and hospitalisation information (reason for attending, length of stay, place of residence at the time) and triage information data (Mental health triage minimum dataset). The data available from these routinely collected data sets are explained in the footnote of table 1. The purpose of these data is to reduce the burden of questions being asked of users and the recall errors of self-report about medications and health services use. These data will be considered in conjunction with outcomes data to develop a detailed understanding of health service and medication use over time including understanding if intervention participation or survey completion is affected by rates of hospitalisation.

Staff will complete an online survey with open-ended questions using Qualtrics survey software (V.2013),87 to collect information at each data collection point about training, recovery programmes occurring at services and engagement of service users and carers in services including the STARS and RSA.75 79

The concurrent nested process evaluation will use quantitative and qualitative data collected to identify contextual (organisational and environmental) factors that affect the intervention. The process evaluation has been organised using the RE-AIM framework as a guide.88 89 The evaluation will examine the reach (representativeness of participants in the study and the intervention), effectiveness (the impact of the intervention on the study outcomes), adoption (proportion and representative of those who participated in each intervention), implementation (fidelity to the implementation of the intervention) and maintenance of the intervention (the extent to which co-design becomes embedded in sites).88–91 The detail of the framework and questions are to be provided in a separate published protocol for the nested process evaluation. Data management protocols can be provided from the University Ethics Approval applications if requested.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise the characteristics of staff, service users and carers. The participants will be analysed in the group that the cluster was assigned to at each time point. A linear mixed effects model will be used to compare the intervention and usual care periods for continuous outcomes and generalised linear mixed effects model for binary outcomes. The model will include intervention status and time as fixed effects and site and individuals as random effects. Where appropriate, organisational and individual factors strongly correlated with the outcome will also be included as fixed effects in the model. These may include: recovery orientation of services and staff attitudes to recovery at baseline, age, gender, education level, work status, quality of life, medication and hospitalisation. The estimated intervention effect will be reported as the mean outcome difference for continuous outcomes and OR for binary outcomes between intervention and control periods, assuming a constant treatment effect over time. The estimated intervention effects will be reported with 95% CIs and p values. A secondary analysis will investigate an interaction effect between intervention and time.55 56 Costs of the delivery of the intervention will be recorded but no economic evaluation will be undertaken. An intention-to-treat analysis strategy will be used.92 Every effort will be made to minimise missing outcome data at each wave and reasons individuals are lost to follow-up will be recorded. Sensitivity analyses will be conducted to assess the robustness of the missing data assumption made in the primary analysis. A detailed analysis plan will be developed for secondary and sensitivity analyses. Analysis will be conducted using Stata statistical software V.13.85

Data monitoring

An advisory and data monitoring committee (ADMC) has been established for the study and a Charter prepared the following guidance from the Data Monitoring and Outcomes Study Group (DAMOCLES).93 The role of the ADMC is to advise investigators regarding the implementation, maintenance and monitoring of the overall conduct of the trial; safeguard the interests of trial participants, assess the safety of the interventions during the trial and address any adverse events in particular harmful events; provide advice and feedback on qualitative elements and the nested process evaluation for the trial (the ADMC Charter has been provided as an online supplementary file number 1). Membership consists of nine international and national experts engaged in research across EBCD, recovery, psychiatry and serious mental illness, complex interventions, RCTs and statistics. The ADMC will meet twice per year to discuss progress and trial conduct. This includes discussion of any serious adverse events. In CORE, the ADMC will not apply the stopping rules and interim analysis as per a clinical trial because (A) the intervention is not therapeutic and (B) the stepped wedge design does not allow for interim analysis since all clusters will not have received the intervention. It is expected that the ADMC will monitor the trial for any serious adverse events related to the intervention and make recommendations to the team on actions related to these which will be reported as required to the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University. Definitions of serious or other adverse events are provided within the ADMC Charter (see online supplementary file 1). Since the intervention has been developed by the lead service user and carer agency, it is believed that the likelihood for the need to discontinue the intervention will be extremely minimal. Membership for the committee is provided in online supplementary file 1.

Ethics and dissemination

The CORE study involves working with vulnerable participants who experience serious mental illness and their carers. To ensure that the needs of these communities are met, the research team has lead investigators from service user and carer agencies who actively contribute to the design, development and implementation of the intervention. Contextual data collected through the model of engagement and translation in earlier parts of the study planning and recruitment of MHCSS providers have been used to inform particular strategies for recruitment, retention and ensuring that implementation of the intervention is as successful as possible. The government departments at Federal and State levels responsible for routine data collection on health service use, pharmaceutical use, hospital admissions and triage have granted ethics approval for participants to consent to access their data (Project 20/2014). Baseline data will be presented in 2015 and trial outcomes in 2017 and published in scientific journals. Only investigators and approved researchers added by ethics approval will have access to the final trial data set. Dissemination will include delivery of conference papers, study updates for staff and the research community via an online blog site, newsletters for users and carers three times per year and knowledge transfer to government and the wider community through presentations, policy briefs and media releases where appropriate. Any protocol amendments will be reported to the responsible University and government ethics committee as trial sponsor and provided to the journal in which this protocol is to be published. Ethics procedures include measures for addressing any unintended harms for intervention participants post-trial by coordination of access to support services and follow-up by professional care workers.

Discussion/conclusion

A stepped wedge design has some advantages and limitations for implementing this kind of trial in such a complex setting. The advantages are that all participants will ultimately receive the intervention and the delivery of the intervention can be staggered to manage the practical and logistical constraints that would come with the delivery of the intervention concurrently in 11 clusters. The staggered implementation of the intervention also allows for time effects to be taken into account on the outcome measures; this provides much greater depth of analysis than a pre-post design. The limitation of the stepped wedge design is that some clusters will wait a long time to receive the intervention, and in populations such as those experiencing severe mental illness, this could result in reduced motivation to continue participation and make contact difficult because of hospitalisation or people moving in and out of services.58 For this reason, the CORE study team has developed and implemented the model of engagement to underpin the trial. The engagement model serves multiple purposes. It seeks to: build enduring relationships with all staff, service users and carers to last the length of the trial; communicate trial requirements to staff to encourage stronger implementation and hence embedding of the intervention into the setting; and to keep service users and carers engaged during the wait periods for the intervention.

The longitudinal design offers a major strength for developing better insights into recovery outcomes over time for people affected by serious mental illness in the community mental health setting. With the current emphasis in mental health policy on developing recovery orientation in services, it is critical to understanding the components from user perspectives that are important in facilitating recovery experiences and how these may result in individual recovery outcomes.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the authors listed, the CORE study is dependent on the commitment provided by the Mental Health Community Support Services partners in the project and the staff, service users and carers of these services. The study acknowledges the ongoing work of the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council (VMIAC) and TANDEM representing Victorian mental health carers in their development of the original Mental Health Experience Co-design methodology (MH ECO).

Footnotes

Funding: The CORE study is funded by the Mental Illness Research Fund and the Psychiatric Illness and Intellectual Disability Donations Trust Fund (MIRF 28). The Mental Illness Research Fund aims to support collaborative research into mental illness that may lead to better treatment and recovery outcomes for Victorians with mental illness and their families and carers.

Contributors: VJP conceived the study in conjunction with staff located in community mental health services. LR contributed to the theoretical model of engagement and translation. PC and TS led the calculation of the sample size and quantitative components of the protocol. All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript, providing written comments on drafts and approving the final version. The trial sponsor is The University of Melbourne, which is responsible for ethical conduct and ensuring that data storage and management procedures are adhered to.

Ethics approval: The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC No.: 1340299.3) has approved this study. The Federal Government Department of Health has approved the collection of Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data and the State Government of Victoria has approved the collection of hospital admission and triage data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Carman K, Dardess P, Maurer M et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter A, Locock L, Ziebland S et al. Collecting data on patient experience is not enough: they must be used to improve care. BMJ 2014;348:g2225 10.1136/bmj.g2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bate P, Robert G. Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: the concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. Oxford: Radcliffe, 2007:224. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert G. Participatory action research: using experience-based co-design to improve the quality of healthcare services. In: Ziebland S, Coulter A, Calabrese JD, Locock L eds. Understanding and using health experiences: improving patient care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:307–10. 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bate P, Robert G. Toward more user-centric OD: lessons from the field of experience-based design and a case study. J Appl Behav Sci 2007;43:41–66. 10.1177/0021886306297014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd H, McKernon S, Mullin B et al. Improving healthcare through the use of co-design. J N Z Med Assoc 2012;125:76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browne G, Hemsley M. Consumer participation in mental health in Australia: what progress is being made? Australas Psychiatry 2008;16:446–9. 10.1080/10398560802357063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg S, Rosen A. It's raining mental health commissions: prospects and pitfalls in driving mental health reform. Australas Psychiatry 2012;20:85–90. 10.1177/1039856212436435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowen S, McSeveny K, Lockley E et al. How was it for you? Experiences of participatory design in the UK health service. CoDesign 2013;9:230–46. 10.1080/15710882.2013.846384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan L, Szebeko D. Co-designing for dementia: the Alzheimer 100 project. Australasi Med J 2009;1:185–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsianakas V, Maben J, Wiseman T et al. Using patients’ experiences to identify priorities for quality improvement in breast cancer care: patient narratives, surveys or both? BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:271–81. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsianakas V, Robert G, Maben J et al. Implementing patient-centred cancer care: using experience-based co-design to improve patient experience in breast and lung cancer services. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2639–47. 10.1007/s00520-012-1470-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiseman T, Tsianakas V, Maben J et al. Improving breast and lung cancer services in hospital using experience based co-design (EBCD). BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011;1:A9–A10. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000020.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locock L, Robert G, Boaz A et al. Testing accelerated experience-based co-design: a qualitative study of using a national archive of patient experience narrative interviews to promote rapid patient-centred service improvement. Health Serv Deliv Res 2014;2:1–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locock L, Robert G, Boaz A et al. Using a national archive of patient experience narratives to promote local patient-centered quality improvement: an ethnographic process evaluation of ‘accelerated’ experience-based co-design. J Health Serv Res Policy 2014;19:200–7. 10.1177/1355819614531565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tollyfield R. Facilitating an accelerated experience-based co-design project. Br J Nurs 2014;23:134–9. 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.3.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piper D, Iedema R, Gray J et al. Utilizing experience-based co-design to improve the experience of patients accessing emergency departments in New South Wales public hospitals: an evaluation study. Health Serv Manage Res 2012;25:162–72. 10.1177/0951484812474247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iedema R, Merrick E, Piper D et al. Codesigning as a discursive practice in emergency health services: the architecture of deliberation. J Appl Behav Sci 2010;46:73–91. 10.1177/0021886309357544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient-centred care: improving quality and safety through partnerships with patients and consumers/Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Darlinghurst, NSW: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrubba M, Melder A. Consumer co-design in the emergency department: a systematic review Melbourne Australia. Centre for Clinical Effectiveness Monash Innovation and Quality Monash Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The King's Fund. Experience Based Co-Design Toolkit. United Kingdom: The King's Fund, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spaniol L, Koehler M, Hutchinson D. The recovery workbook: practical coping and empowerment strategies for people with psychiatric disabilities. Revised ed 2009.

- 24.Barbic S, Krupa T, Armstrong I. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a modified recovery workbook Program: preliminary findings. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:491–7. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook J, Copeland M, Floyd C et al. A randomized controlled trial of effects of wellness recovery action planning on depression, anxiety, and recovery. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:541–7. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukui S, Starnino V, Susana M et al. Effect of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) participation on psychiatric symptoms, sense of hope, and recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2011;34:214–22. 10.2975/34.3.2011.214.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunn E, Rogers S, Dori S et al. Results of an innovative university-based recovery education program for adults with psychiatric disabilities. Adm Policy Ment Health 2008;35:357–69. 10.1007/s10488-008-0176-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Bendall S, Lederman R et al. On the HORYZON: moderated online social therapy for long-term recovery in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2013;143:143–9. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloyd-Evans B, Mayo-Wilson E, Harrison B et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:39 10.1186/1471-244X-14-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinman M, George P, Dougherty R et al. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 2014;65:429–41. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson EL, House AO. Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. BMJ 2002;325:1265 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penn DL, Uzenoff SR, Perkins D et al. A pilot investigation of the Graduated Recovery Intervention Program (GRIP) for first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2011;125:247–56. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DoH. Closing the gap: priorities for essential change in mental health. London: Crown, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centre for Mental Health, Department of Health, Mind, NHS Confederation Mental Health Network, Rethink Mental Illness, Turning Point. No Health Without Mental Health: implementation framework. London: Mental Health Strategy Branch, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MHCC. Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary, Canada: Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.New Freedom Commission on Health. Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.COAG. The roadmap for National Mental Health Reform 2012–2022. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.DoHA. A national framework for recovery-oriented mental health services: policy and theory. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Australian Health Ministers. 4th National Mental Health Plan—an agenda for collaborative government action in mental health 2009–2014. Canberra: Australian Government, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mental Health Consumer Outcomes Task Force. Mental health statement of rights and responsibilities. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Community Services and Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Australian Government. Implementation guidelines for non-government community services. Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Australian Government. Implementation guidelines for public mental health services and private hospitals. Commonwealth of Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.New Zealand Ministry of Health. Rising to the challenge. The Mental Health and Addiction Service Development Plan 2012–2017. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson L, Roe D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: one strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. J Ment Health 2007;16:459–70. 10.1080/09638230701482394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andresen R, Caputi P, Oades L. Do clinical outcome measures assess consumer-defined recovery? Psychiatry Res 2010;177:309–17. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drake R. Recovery and severe mental illness: description and analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kidd S, Kenny A, McKinstry C. From experience to action in recovery-oriented mental health practice: a first person inquiry. Action Research, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fairhurst K, Weavell W. Co-designing mental health services—providers, consumers and carers working together. Aust J Psychosoc Rehabil 2011;54:54–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paton N, Callander R, Cavill M et al. Collaborative quality improvement: consumers, carers and mental health service providers working together in service co-design. Australas Psychiatry 2013;21:78–9. 10.1177/1039856212465347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Callander R, Ning L, Crowley A et al. Consumers and carers as partners in mental health research: reflections on the experience of two project teams in Victoria, Australia. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2011;20:263–73. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials 2013. 2013-01-09 09:40:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Hemming K, Girling A, Haines T et al. Protocol: Consort extension to stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial 2014.

- 54.Mdege ND, Man MS, Taylor CA et al. Systematic review of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials shows that design is particularly used to evaluate interventions during routine implementation. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:936–48. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A et al. An epistemology of patient safety research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 2. Study design. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:163–9. 10.1136/qshc.2007.023648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:54 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feldman H, McKinlay S. Cohort versus cross-sectional design in large field trials: precision, sample size, and a unifying model. Stat Med 1994;13:61–78. 10.1002/sim.4780130108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vuchinich S, Flay B, Aber F et al. Person mobility in the design and analysis of cluster-randomized cohort prevention trials. Preventative Sci 2012;13:300–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirano K, Imbens G, Ridder G et al. Combining panel data sets with attrition and refreshment samples. Econometrica 2001;69:1645–59. 10.1111/1468-0262.00260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clavier C, SénéChal Y, Vibert S et al. A theory-based model of translation practices in public health participatory research. Sociol Health Illn 2012;34:791–805. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palmer V, Gunn J, Herrman H et al. Getting to the CORE of the links between engagement, experience and recovery outcomes. New Paradigm 2015:41–5. [Google Scholar]

- 62.DoH. Reforming community support services for people with a mental illness: reform framework for Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and Support Services. Victoria: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Furimsky I, Cheung AH, Dewa CS et al. Strategies to enhance patient recruitment and retention in research involving patients with a first episode of mental illness. Contemp Clin Trials 2008;29:862–6. 10.1016/j.cct.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zullino D, Conus P, Borgeat F et al. Readiness to participate in psychiatric research. Can J Psychiatry 2003;48:480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Senturia YD, McNiff Mortimer K, Baker D et al. Successful techniques for retention of study participants in an inner-city population. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:544–54. 10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00032-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Candilis PJ, Geppert CM, Fletcher KE et al. Willingness of subjects with thought disorder to participate in research. Schizophr Bull 2006;32:159–65. 10.1093/schbul/sbj016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schäfer I, Burns T, Fleischhacker WW et al. Attitudes of patients with schizophrenia and depression to psychiatric research: a study in seven European countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2011;46:159–65. 10.1007/s00127-010-0181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morse EV, Simon PM, Besch CL et al. Issues of recruitment, retention, and compliance in community-based clinical trials with traditionally underserved populations. Appl Nurs Res 1995;8:8–14. 10.1016/S0897-1897(95)80240-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Poythress NG. Obtaining informed consent for research: a model for use with participants who are mentally ill. J Law Med Ethics 2002;30:367 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2002.tb00405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goodrick D, Bhagwandas R. Evaluation of Mental Health Experience Co-Design. Melbourne, Victoria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corrigan PW, Salzer M, Ralph RO et al. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:1035–41. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McNaught M, Caputi P, Oades LG et al. Testing the validity of the recovery assessment scale using an Australian sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2007;41:450–7. 10.1080/00048670701264792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lusczakoski K, Olmos-Gallo PA, McKinney CJ et al. Measuring recovery related outcomes: a psychometric investigation of the recovery markers inventory. Community Ment Health J 2014;50:896–902. 10.1007/s10597-014-9728-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Drapalski AL, Medoff D, Unick GJ et al. Assessing recovery of people with serious mental illness: development of a new scale. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:48–53. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Connell M, Tondora J, Croog G et al. From rhetoric to routine: assessing perceptions of recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2005;28:378–86. 10.2975/28.2005.378.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell-Orde T, Chamberlin J, Carpenter J et al. Measuring the promise: a compendium of recovery measures, volume II. Cambridge: Human Services Research Institute, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 77.da Rocha NS, Power MJ, Bushnell DM et al. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-Item Index: comparative psychometric properties to its parent WHOQOL-BREF. Value Health 2012;15:449–57. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schmidt S, Mühlan H, Power M. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:420–8. 10.1093/eurpub/cki155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crowe T, Deane F, Oades L et al. Effectiveness of a collaborative recovery training program in Australia in promoting positive views about recovery. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:1497–500. 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Woertman W, de Hoop E, Moerbeek M et al. Stepped wedge designs could reduce the required sample size in cluster randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:752–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014.

- 82.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bower P, Brueton V, Gamble C et al. Interventions to improve recruitment and retention in clinical trials: a survey and workshop to assess current practice and future priorities. Trials 2014;15:399 10.1186/1745-6215-15-399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Granirer D. Stand up for mental health. Vancouver, Canada: David Granirer, 2014. http://standupformentalhealth.com/ (accessed 18 Sept 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 85.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013.

- 86.Picker Institute. Friends and Family Test Resources. Oxford, UK: Picker Institute Europe, 2012. http://www.pickereurope.org/fft-resources/ (accessed 15 Aug 2014).

- 87.Qualtrics. Qualtrics Software Version 2013 of the Qualtrics Research Suite. Provo, UT: Qualtrics, 2005.