Abstract

Objectives

About 100 000 people present to hospitals each year in England with an epileptic seizure. How they are managed is unknown; thus, the National Audit of Seizure management in Hospitals (NASH) set out to assess prior care, management of the acute event and follow-up of these patients. This paper describes the data from the second audit conducted in 2013.

Setting

154 emergency departments (EDs) across the UK.

Participants

Data from 4544 attendances (median age of 45 years, 57% men) showed that 61% had a prior diagnosis of epilepsy, 12% other neurological problems and 22% were first seizure cases. Each ED identified 30 consecutive adult cases presenting due to a seizure.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Details were recorded of the patient's prior care, management at hospital and onward referral to neurological specialists onto an online database. Descriptive results are reported at national level.

Results

Of those with epilepsy, 498 (18%) were on no antiepileptic drug therapy and 1330 (48%) were on monotherapy. Assessments were often incomplete and witness histories were sought in only 759 (75%) of first seizure patients, 58% were seen by a senior doctor and 57% were admitted. For first seizure patients, advice on further seizure management was given to 264 (27%) and only 55% were referred to a neurologist or epilepsy specialist. For each variable, there was wide variability among sites that was not explicable. For the sites who partook in both audits, there was a trend towards better care in 2013, but this was small and dwarfed by the intersite variability.

Conclusions

These results have parallels with the Sentinel Audit of Stroke performed a decade earlier. There is wide intersite variability in care covering the entire care pathway, and a need for better organised and accessible care for these patients.

Keywords: AUDIT, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, seizure, care pathways

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This audit consisted of an unselected population from most hospital emergency departments across the UK.

The number of patients is large, and the difference between well and poor performing sites of such a magnitude that it is unlikely chance is an explanation.

Opportunities for improving the care provided to these patients are clear and substantial.

As with any audit data, we could only record what was written in the patient records. However, for example, not having a temperature recorded would suggest that it was not considered important; a principle enshrined in the legal system.

The steering group had input from clinical staff (including neurologists, emergency and acute physicians, general practitioners and specialist nurses), patient charities and commissioners.

Introduction

Epilepsy is common with a prevalence of around 0.5% and a lifetime incidence of 3–5%.1 Appropriate drugs, either singly or in combination, can prevent seizures in most people with epilepsy,2 3 while for those with treatment refractory epilepsy, strategies can be put in place to better manage seizures in the community to avoid hospital attendance. Yet there are some 40 000 epilepsy-related admissions to English hospitals per annum (1.4% of all emergency medical admissions), and an estimated 60 000 more attendances at emergency departments (ED). This suggests suboptimal control for many patients, as well as inadequate strategies to manage acute seizures in the community. There is clear evidence that seizure control is the largest determinant of quality of life for people with epilepsy4 and failure to control seizures will, therefore, come at a significant cost to the individual, the health service and wider society. While epidemiological studies and clinical trials demonstrate that around 70% of patients can enter a seizure remission with optimum treatment, evidence suggests that only 50% of UK patients achieve seizure control.5

A review in 2004 estimated the total annual cost of epilepsy to the UK at €1.5 billion,6 but little is known about the organisation and delivery of adult epilepsy care. This considerable knowledge gap makes it difficult to develop a coherent strategic plan for epilepsy services.

While there have been no previous national audits of adult epilepsy care in the UK, both the sentinel audit of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy7 and a confidential enquiry into maternal deaths8 highlighted inadequacies in the provision of care. The Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) in 20009 surveyed 2400 people with epilepsy and 500 epilepsy specialists. Their report highlighted problems with access, equity and co-ordination of care, which is a recurring theme in the UK. The Department of Health acknowledged the report but made no specific recommendations aside from stating that “Some of CSAG's recommendations will need consideration at local level to see whether they represent an appropriate way forward.” No resources followed and nor was there a strategy to monitor developments.

National audits of other common conditions, for example, myocardial infarction,10 stroke,11 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)12 and others have been influential over the last decade in helping services identify deficiencies, improve care and, consequently, improve outcomes. Issues addressed have included the way services are structured and the detailed processes of care. Few of the recommendations have been new, but the audit process provided a stimulus for hospitals to achieve change that had previously eluded them.

Twelve years on from the CSAG report, the National Audit of Seizure management in Hospitals (NASH) set out to describe and understand the organisation of epilepsy care and had two cycles of data collection, the first in 2011 and the second in 2013. NASH aims to describe the variations in care delivered; and thus, set out options and opportunities for improving care. This paper reports on the clinical data for 4544 seizure-related attendances from 154 hospitals in 2013.

Methods

NASH was coordinated from the University of Liverpool and overseen by a multidisciplinary steering committee consisting of representatives from neurology, emergency medicine, a patient charity and each of the nations comprising the UK (see acknowledgements section). We decided to focus on patients presenting to ED, who were either admitted or discharged, as this would provide an index point and an opportunity to identify first seizure and new epilepsy cases as well as established cases with uncontrolled seizures. We aimed to collect information about acute, prior and onward care to identify where current service provision could be improved across the whole patient pathway.

Two separate proformas were developed; the clinical proforma captured the clinical care pathway for individual patients, while the organisational proforma assessed the facilities and staffing available. The questions were based on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines2 3 augmented by the practical experience of the steering committee, particularly in the area of care delivery. The clinical proforma was divided into sections covering the care antecedent to the presenting seizure, the care at hospital (in the ED and on medical wards), and the future plans for the patient. In each section, recognising the constraints on data collectors, a limited range of items was collected.

The two proformas were piloted with duplicate collections from 60 patients across 10 sites, and the questions amended and refined to reduce ambiguities and inconsistencies. This paper reports on the data from the clinical proforma.

One hundred and sixty-five UK trusts with an ED were approached and each site was asked to identify up to 30 consecutive adult patients who presented at the ED from 1 January 2013 with an episode thought to have been a seizure (the following ICD10 codes were used as an indication of potential seizure: G40.0, G40.1, G40.2, G40.3, G40.4, G40.5, G40.6, G40.7, G40.8, G40.9, G41.0. G41.1, G41.2, G41.8, G41.9, R56.1 and R56.8), and where the seizure was the primary reason for their admission/attendance.

Data were entered anonymously into a bespoke web-based audit system. Online help was available for the majority of questions. Data entry took place from June to September 2013, when follow-up information should have been available. If an individual attended more than once, each attendance was treated as a separate event.

Results are shown as the percentage for all patients, and give then the median and IQR of site performance. We allowed for the widest interpretation of care delivery so that, for example, contact with any one of the neurologist, epilepsy specialist nurse, general practitioner with special interest in epilepsy, paediatric neurologist, learning disability psychiatrist or paediatrician, would constitute contact with epilepsy services.

Results

Patient characteristics

One hundred and fifty-four sites took part representing 132 trusts (80% of those who were approached), and 101 of these sites also took part in the first iteration of NASH. There were no systematic differences in hospital size, type or geographical distribution associated with participation in either round. In the first round of data collection, clinical data were collected on 3755 patients (median age 44 years (IQR 29–60); 57% men). In total 82% (3077/3755) of the clinical proformas were completed by doctors, 11% (413/3755) by nurses, and 7% (264/3755) by audit staff or other health professionals. In the second round of data collection, clinical data were collected on 4544 patients (median age 45 years (IQR 31–56); 57% men).

The patient characteristics of those included and the results recorded were very similar for the two audit rounds. There was a small trend towards better values in round two, which was small in the context of the wide variability described among sites. We present the data for the second round of NASH and supply the first round as online supplementary tables S1–S3. Less than 2% of data for any variable were missing—a level that could not explain the variability between sites or the very significant deficiencies in care delivery—no further corrections were applied.

Patients were divided into the following three categories:

Those recorded as having known epilepsy prior to attendance (n=2759; 61%);

Those known to have had previous seizures or blackouts, but not a diagnosis of epilepsy (n=767; 12%);

Those with likely first seizures and no previous seizures or blackouts or diagnosis of epilepsy (n=1011; 22%).

Treatment prior to the seizure episode

Of those with a known diagnosis of epilepsy, 82% (2261/2759) were documented as taking antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment; 48% (1330/2759) were on monotherapy, and 34% (931/2759) were on two or more AEDs. Sodium valproate was the most commonly documented AED (34%; 935/22 759) of which 518 (55%) were on monotherapy (table 1). Only 18% (492/2759) were on carbamazepine (44%; n=218 monotherapy), 21% (581/2759) lamotrigine (40%; n=231 monotherapy), 22% (598/2759) levetiracetam (31%; n=186 monotherapy) and 10% (279/2759) phenytoin (33%; n=91 monotherapy).

Table 1.

Treatment prior to presentation (percentage of all patients and median (IQR) for hospital sites)

| Patients with diagnosis of epilepsy |

Patients with known blackouts or seizures, but no epilepsy |

Patients with neither prior epilepsy nor blackouts/seizures |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) n=2759 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | Mean (%) n=767 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | Mean (%) n=1011 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | |

| Two or more drugs as polytherapy | 33.7 | 33.3 | 23–46 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0–0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0–0 |

| Monotherapy | 48.2 | 47.8 | 38–60 | 17.3 | 12.5 | 0–25 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0–0 |

| No AEDs | 18.1 | 14.3 | 9–23 | 80.3 | 85.7 | 72–100 | 95.0 | 100.0 | 100–100 |

| Been seen by a neurological specialist in the previous 12 months | 37.1 | 38.3 | 21–53 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 0–43 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0–12 |

AED, antiepileptic drug.

In total 63% (1736/2759) of those with known epilepsy had no evidence of contact with an epilepsy specialist recorded in the year preceding their attendance, rising to over 67% (900/1330) of those on monotherapy and 77% (382/498) for those on none.

The intersite ranges of the proportion on polytherapy (0–75%) and having seen a specialist in the preceding year (0–100%) varied widely.

As would be expected, the pattern in the other groups was different. Of those documented with no prior epilepsy diagnosis, a few were on AED therapy but we were unable to retrospectively determine if this was because of error in the clinical documentation or because the drugs had been prescribed for a different indication.

Assessment on arrival

Table 2 shows a selection of the variables collected in the audit and demonstrates considerable variation in documented practice between sites for each of the subgroups. Glasgow Coma Scale score was recorded in the majority of cases, but other elements of the neurological examination were variably documented. Plantar reflex testing and fundal examination were much less commonly documented, suggesting variation in the thoroughness of the clinical examination undertaken. Recording an attempt to ascertain an eyewitness history was done in 69% (3123/4544) of cases and even routine measurements, such as temperature, were variably recorded. The results were similar when analysis was restricted to those admitted to wards compared with those discharged home from the ED.

Table 2.

A selection of the assessments made for patients presenting with seizure (percentage of all patients and median (IQR) for hospital sites)—a full list is available from http://www.nashstudy.org

| Patients with diagnosis of epilepsy |

Patients with known blackouts or seizures, but no epilepsy |

Patients with neither prior epilepsy nor blackouts/seizures |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) n=2759 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | Mean (%) n=767 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | Mean (%) n=1011 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score | 89.0 | 91.8 | 82–99 | 91.8 | 100.0 | 86–100 | 90.3 | 100.0 | 83–100 |

| Plantar reflex tested | 30.0 | 25.0 | 13–42 | 35.9 | 33.3 | 14–59 | 41.7 | 40.0 | 20–60 |

| Fundi examined | 12.6 | 4.9 | 0–12 | 15.6 | 0.0 | 0–25 | 18.5 | 0.0 | 0–25 |

| Eyewitness history taken or sought | 66.3 | 68.2 | 52–85 | 69.2 | 75.0 | 50–100 | 75.1 | 80.0 | 62–100 |

| Temperature | 92.1 | 94.4 | 86–100 | 93.9 | 100.0 | 100–100 | 91.4 | 100.0 | 88–100 |

| Review by a senior doctor in ED | 57.5 | 56.3 | 42–73 | 59.2 | 60.0 | 40–80 | 58.6 | 60.0 | 40–80 |

| Documentation of general alcohol intake | 37.2 | 36.6 | 21–48 | 53.8 | 50.0 | 33–75 | 48.0 | 40.0 | 25–67 |

ED, emergency department.

Just under 60% (2636/4544) of the patients were seen by a doctor with more than 5 years of experience, and this was similar whether the patient had known epilepsy or was a first presentation, and whether the patient was admitted to hospital or discharged directly (59.2%; n=1539 vs 56.5%; n=1091).

Management of patients

There was very wide variability in the use of investigations between hospitals (table 3).

Table 3.

A selection of the investigations and actions recorded for patients presenting with seizure (percentage of all patients and median (IQR) for hospital sites; excludes 40 patients who died in hospital)

| Patients with diagnosis of epilepsy |

Patients with known blackouts or seizures, but no epilepsy |

Patients with neither prior epilepsy nor blackouts/seizures |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) n=2759 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | Mean (%) n=767 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | Mean (%) n=1011 | Site median (%) n=154 | IQR by site | |

| ECG | 68.6 | 69.6 | 57–83 | 79.3 | 85.7 | 67–100 | 86.8 | 100.0 | 80–100 |

| Either CT or MRI | 22.4 | 19.0 | 10–31 | 32.9 | 33.3 | 13–56 | 55.8 | 54.5 | 33–78 |

| Admission | 55.8 | 50.0 | 38–82 | 51.6 | 50.0 | 28–94 | 65.0 | 66.7 | 43–100 |

| Management of future seizures discussed with the patient or carers | 28.0 | 18.6 | 10–38 | 26.8 | 20.0 | 0–39 | 26.7 | 20.0 | 0–43 |

| Any epilepsy specialist referral as an outpatient | 43.6 | 42.9 | 27–59 | 59.0 | 60.0 | 41–80 | 54.9 | 54.5 | 38–75 |

| Seen by epilepsy specialist at/in the hospital | 21.6 | 18.2 | 9–33 | 18.9 | 12.5 | 0–33 | 19.1 | 10.0 | 0–25 |

| Either or both of the two rows above | 48.8 | 50.0 | 30–67 | 63.3 | 66.7 | 44–83 | 60.6 | 62.5 | 43–80 |

Even NICE guideline recommended investigations, such as an ECG,2 13 were documented in only 86.8% (878/1011) with a range from 0% to 100% of patients who presented after suffering their first suspected seizure.

Our audit did not set out to make a judgement as to when admission was necessary, but the proportions admitted to hospital ranged from 0% to 100%, and the documentation of advice given to patients was also very variable. For example, less than 30% (1235/4487; range 0–100%) in any category had formal advice documented about what to do should further seizures occur. Of those with a first seizure presentation, only 35% (273/785) had documented evidence when they were asked about driving (range 0–100%).

Just over half of the patients had documented evidence that they were either seen by a neurologist in the episode or referred on to be seen later by a neurologist or epilepsy specialist. For those with a first seizure, this figure was 61% (599/988) (IQR 22–71), despite current NICE guidance2 13 that first seizure patients should be seen by an epilepsy specialist within 2 weeks.

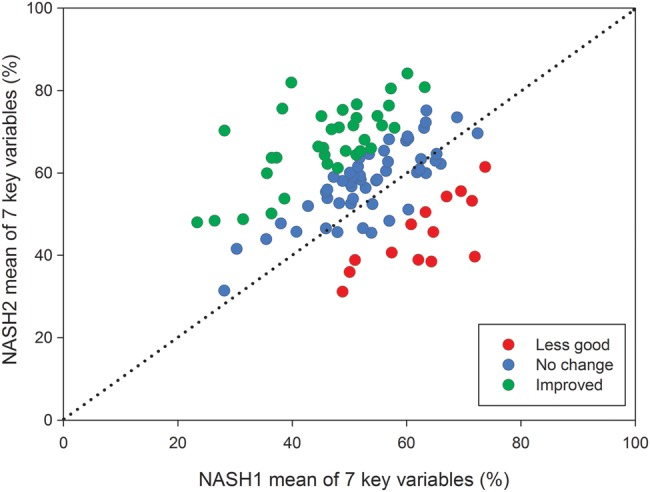

One hundred and one sites took part in both rounds of the audit. When comparing means for individual variables, with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, differences were inconsistent and within the range of chance. However, by amalgamating seven variables (chosen at the time of the first audit as key illustrators across the pathway) there was a small but statistically significant improvement (mean 52.1–59.5, p<0.01), which is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of NASH1 and NASH2 data for 101 hospital sites that took part in both audit rounds: mean values of seven key variables (temperature taken in the emergency department; eyewitness statement taken or sought; plantars examined; ECG performed; the patient had some neurological input during their attendance, or was referred to a neurologist as an outpatient; discussion around driving took place with the patient; known epilepsy patients who were sent home on at least one antiepileptic drug).

Discussion

This is the first national adult epilepsy audit in the UK and probably worldwide. It has gone through two cycles of data collection and the fact that results for 2011 and 2013 are almost identical provides some assurance that the methods are robust. The methods mirror those adopted for other national audits (eg, stroke,11 COPD12), using a specific event to identify and examine each case. A seizure is likely to be similarly understood across the country; it may signal the onset of new epilepsy, be due to another illness (eg, alcohol withdrawal), or be a marker that control has failed in a patient with known epilepsy. Hospitals were asked to record sequential cases presenting to the ED and so there should have been no selection bias. Some clerical errors are inevitable within audit studies, but while this makes it more difficult to interpret data with the small numbers at local level, it does not invalidate the broad national picture.

The audit proforma were developed with expert medical and patient input, and the questionnaires tested to confirm robust repeatability of data collection. Like the stroke audit, most data were returned by doctors and the κ statistic was similar.14 A retrospective audit can only record what was written in the notes and while there is a medicolegal principle that ‘not recorded’ implies ‘not done’, an unknown proportion of the recorded variation will be due to differences in documentation and the availability of relevant information to those undertaking data extraction. National guidelines2 13 had relatively few specific recommendations for the management of seizures acutely, but many of the variables might be considered obvious (eg, recording of temperature, seeking an eyewitness view of the episode given that patients cannot describe their own seizure, or advice about driving). Since this project began, NICE15 has produced quality standards, and seven of the nine relate to aspects covered by NASH and were perhaps influenced by the first round of data collection.

Nevertheless, participation from 154 sites, and about three-quarters of trusts with EDs, was most encouraging for a condition that does not feature on any national priority list and makes it probable that the results are generalisable.

We divided patients into three groups, one of which is a cohort of patients where the diagnosis of epilepsy was not clear from the audited record. We report them as a separate group to avoid contaminating the other groups, because we cannot retrospectively add to the diagnosis. Given such uncertainty, one might speculate that they would have required more detailed attention, but this was not the case.

Care before the event

Of the emergency attendees with a prior diagnosis of epilepsy, just over one-third had evidence of having seen an epilepsy specialist in the previous year. Even allowing for under-recording, it seems that a significant proportion of patients with active epilepsy are not being seen within specialist services. This represents a missed opportunity to improve seizure control and thereby, avoid acute hospital attendance and admission. It is likely that many ED attendances can be avoided through improved community and outpatient services, and through better management of acute seizures in the community. Nearly two-thirds of patients with known epilepsy were documented as being on either no therapy or monotherapy, so it seems likely there are additional treatment possibilities that could have prevented many of these seizures.

Focal epilepsy is the most common epilepsy type, most likely to be refractory and often not best treated with sodium valproate. Yet sodium valproate was the most commonly prescribed AED. This may reflect outdated practice and demonstrates another area where specialist input may benefit patients and prevent seizure occurrence.

Refractory disease usually necessitates polytherapy, which requires up-to-date knowledge of the rapidly expanding treatment options. A breakthrough seizure in a previously well-controlled patient has huge potential consequences for them and we had, therefore, expected most patients on polytherapy to have a record of specialist supervision. The relatively low proportion of known epilepsy patients who had documented evidence of being seen in the previous year fits with the CSAG report,9 suggesting that access to ongoing care may be lacking and we recommend that clinical commissioners use this report as an opportunity to review the available services and access arrangements.

Care at hospital

We also recorded considerable variation in the documented care received by seizure patients in hospital, both in the ED and for those subsequently admitted to a hospital bed. The fact that some hospitals are able to document high standards of care for almost all patients demonstrates what can be achieved and should act as encouragement to those in the lower quartiles. Guidelines2 3 stress the importance of a witness history, yet attempts to achieve this are variably documented in the ED and hospital notes.

We would strongly recommend that acute hospitals review their processes and documentation in the light of these findings, and seek ways to improve performance so that the overall degree of variation is reduced.

Care after hospital

The same pattern of a low–median documented performance and wide interhospital variability applies to the use of investigations, giving of patient advice and onward referral for expert neurological input, and we recommend that the reasons for this be explored and addressed within each healthcare community. Almost all hospitals have several neurology clinics weekly (either from their own staff or from visiting specialists), but seizure patients do not seem to be reaching these clinics. Possible reasons could be a failure to refer, barriers to referral (for instance, intrahospital referral not being allowed), a lack of suitable services or a combination of these. This should be examined and remedied at local level. It is unlikely that any other clinicians will be taking on the specialist management.

What may this mean?

This audit shows considerable variation in the documented care of patients with seizures attending hospital. Similar variability has been reported from a recent national paediatric epilepsy audit in the UK.16 It is important to emphasise that this variation was identified across the whole patient pathway and indicates that if community care were better, many of these episodes could have been prevented. Therefore, alongside improvements in hospital care, entire healthcare communities need to work with their commissioners to identify how best to improve services for this patient group in their area.

Some hospitals performed very well in the audit—showing that all the audited items are recordable and collectable. One major challenge is that most adult epilepsy expertise exists in adult neurology centres of excellence and in many district hospitals, there is only a visiting service without an epilepsy ‘champion’ to promote a local service. Epilepsy care can lose out to cancer, cardiac disease and other chronic conditions if there are no physicians present to argue for it.

Seizures have enormous consequences for patients, and can lead to problems with their driving and employment status, together with general quality of life and well-being. In addition, there is a large financial burden on the NHS. If more patients got to see epilepsy specialists and had appropriate treatment regimes, then apart from the benefits to the patients, fewer admissions and fewer ED attendances would bring about large savings. Evidence from Ireland suggests that a few simple measures can contribute significant cost savings in epilepsy care without compromising safety.17

Typically, epileptic seizures present to secondary care where specialists are based in tertiary units and day-to-day care is provided in primary care. UK commissioning of neurological conditions has struggled to set standards that favour the patient wherever they are in the system. The new NICE quality standards15 may be a first step, but it is clear there are missed opportunities at all levels of care to reduce variation. This is an important challenge for clinical commissioners and healthcare providers, with an opportunity to reduce the 40 000 seizure-related admissions that occur each year into English hospitals.

The very wide variability between sites in this study and the lack of change over 2 years is comparable to the results of the first two rounds of the stroke audit in 1998.18 At that time, stroke was considered an overlooked condition, and this has progressively improved following the introduction of guidelines and national audits that helped raise the profile. Since then, with the strong support of clinicians, patient organisations and others, stroke care and outcomes have improved.19 A key thread to this improvement journey has been the establishment of stroke physicians, that is, specialists based in and immediately available to the acute service.

A Royal College of Physicians report20 has suggested that the specialty of ‘acute neurology’ ought to be present in every hospital and these data support that recommendation. As well as potentially creating a more efficient seizure management process, this could bring benefits for other acute neurological conditions. If the improvement in readmission rates within a year (45% down to 8.9%) achieved in an Irish study17 were replicated, about 9000 admissions per annum could be avoided, benefitting hard-pressed emergency services and more importantly, people with epilepsy. Commissioning for such change will not be easy and will challenge long-established neurology structures and will have to be done without harming the expertise in those centres. However, perhaps the guiding principle is that the expertise is needed where the patients are and that means within the secondary sector.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the substantial contribution from the data collectors in 154 hospitals and the steering group in this work without whom nothing would have been possible. The steering group is comprised of Duncan Appelbe (University of Liverpool), Richard Appleton (Alder Hey Children's Hospital), Karen Scott (University of Liverpool), Adrian Boyle (College of Emergency Medicine), John Craig (Belfast Health and Social Care Trust), Colin Dunkley (Epilepsy 12), Graham Faulkner (Epilepsy Society), Mel Goodwin (Epilepsy Nurses Association), Jane Hanna (SUDEP Action), Paul Jarman (ABN), Jamie Kirkham (University of Liverpool), John Paul Leach (Southern General Hospital), Stephen Nash (College of Emergency Medicine), Angie Pullen (Epilepsy Action), Greg Rogers (RCGP Clinical Champion for Epilepsy Care) and Phil Smith (University Hospital of Wales and ILAE).

Footnotes

Contributors: AGM and MGP had the idea, then planned and conducted the study with PAD. JJK and PAD extracted the study data and performed statistical analysis. All authors assisted in formulation of the audit questions (together with the study steering group), contributed to and developed the final manuscript.

Competing interests: AGM has been reimbursed for giving lectures for Sanfoi and UCB Pharma Ltd.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Further figures from both audits are in the St. Elsewhere's reports available for download from http://www.nashstudy.org.uk

References

- 1.Hauser WA, Hesdorffer DC. Epilepsy: frequency, causes and consequences. New York: Demos Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. NICE clinical guideline 137. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults: A national clinical guideline Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 2003.

- 4.Baker GA, Jacoby A, Buck D et al. . Quality of life of people with epilepsy: a European study. Epilepsia 1997;38:353–62. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran NF, Poole K, Bell G et al. . Epilepsy in the United Kingdom: seizure frequency and severity, anti-epileptic drug utilization and impact on life in 1652 people with epilepsy. Seizure 2004;13:425–33. 10.1016/j.seizure.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugliatti M, Beghi E, Forsgren L et al. . Estimating the cost of epilepsy in Europe: a review with economic modelling. Epilepsia 2007;48:2224–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna NJ, Black M, Sander JW et al. . The National Sentinel Clinical Audit of Epilepsy-Related Death: Epilepsy—death in the shadows. The Stationery Office, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis G, ed. Why mothers die 2002–2002: the sixth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London: RCOG Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.CSAG. Services for patients with epilepsy. London: Department of Health, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birkhead JS, Walker L, Pearson M et al. . Improving care for patients with acute coronary syndromes: initial results from the National Audit of Myocardial Infarction Project (MINAP). Heart 2004;90:1004–9. 10.1136/hrt.2004.034470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudd AG, Hoffman A, Down C et al. . Access to stroke care in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: the effect of age, gender and weekend admission. Age Ageing 2007;36:247–55. 10.1093/ageing/afm007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price LC, Lowe D, Hosker HS et al. . UK National COPD Audit 2003: impact of hospital resources and organisation of care on patient outcome following admission for acute COPD exacerbation. Thorax 2006;61:837–42. 10.1136/thx.2005.049940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Transient loss of consciousness (“blackouts”) management in adults and young people. NICE clinical guideline 109. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gompertz PH, Irwin P, Morris R et al. . Reliability and validity of the Intercollegiate Stroke Audit Package. J Eval Clin Pract 2001;7:1–11. 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Quality standard for the epilepsies in adults. NICE quality standard 26. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epilepsy 12 National Report. RCPCH 2012.

- 17.Iyer PM, McNamara PH, Fitzgerald M et al. . A seizure care pathway in the emergency department: preliminary quality and safety improvements. Epilepsy Res Treat 2012;2012:7 10.1155/2012/273175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudd AG, Irwin P, Rutledge Z et al. . The National Sentinel Audit for Stroke: a tool for raising standards of care. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1999;33:460–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudd AG, Hoffman A, Irwin P et al. . Stroke units: research and reality. Results from the National Sentinel Audit of Stroke. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:7–12. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royal College of Physicians. Local adult neurology services for the next decade. Report of a working party London: RCP, 2011. [Google Scholar]