Abstract

Objectives

There is a controversy about the impact of economic crisis on suicide rates in Greece. We analysed recent suicide data to identify who has been most affected and the relationships to economic and labour market indicators.

Setting

Greece.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Age-specific and sex-specific suicide rates in Greece for the period 2003–2012 were calculated using data provided by the Hellenic Statistical Authority. We performed a join-point analysis to identify discontinuities in suicide trends between 2003 and 2010, prior to austerity, and in 2011–2012, during the period of austerity. Regression models were used to assess relationships between unemployment, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and suicide rates for the entire period by age and sex.

Results

The mean suicide rate overall rose by 35% between 2010 and 2012, from 3.37 to 4.56/100 000 population. The suicide mortality rate for men increased from 5.75 (2003–2010) to 7.43/100 000 (2011–2012; p<0.01). Among women, the suicide rate also rose, albeit less markedly, from 1.17 to 1.55 (p=0.03). When differentiated by age group, suicide mortality increased among both sexes in the age groups 20–59 and >60 years. We found that each additional percentage point of unemployment was associated with a 0.19/100 000 population rise in suicides (95% CI 0.11 to 0.26) among working age men.

Conclusions

We found a clear increase in suicides among persons of working age, coinciding with austerity measures. These findings corroborate concerns that increased suicide risk in Greece is a health hazard associated with austerity measures.

Keywords: suicides, Greece, austerity, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study includes the most recent official data, covering the years 2011 and 2012, permitting a preliminary assessment of the effect of radical austerity on suicide rates.

We quantitatively assess the association between changes in unemployment on age-specific and sex-specific suicide rates in Greece.

As individual-level data were unavailable, we used aggregate data with the limitations of all ecological studies.

Introduction

The economic crisis has hit Greece especially hard. As it attempted to refinance its already high debt burden, detailed examination raised questions about its economic data.1 Concerns that it might have to default on its debt led to a series of bailout packages from the European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund (the troika). However, these came at a price as Greece was forced to implement severe austerity starting in 2010.The government was required to cut spending by €28 billion in 2010–2011, with a further €13 billion in 2012–2014. Overall, this was equivalent to almost 32% of Greece's 2012 Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The first three austerity packages, in 2010, included cuts to public sector jobs and salaries and to pensions, increases in indirect taxes and privatisation of state-owned industries. As a result, the Greek economy shrank by almost a quarter between 2008 and 2012 and unemployment nearly doubled, from 12.7% in 2010 to 24.3% in 2012. By February 2012, 20 000 additional Greeks had been rendered homeless and 20% of shops in the historic centre of Athens were empty.2 It was estimated that almost 1 in 10 of the population of greater Athens was visiting a soup kitchen daily.3

Research on the health consequences of this crisis has stimulated much controversy. Early research pointing to an increase in suicides4 and suicide attempts5 was dismissed by critics who argued that it was premature to reach a conclusion and anyway, given Greece's historically low suicide rate, the numbers were too low to reach a definitive conclusion. In addition, other studies have reported a range of adverse health consequences associated with austerity in Greece, including major depression, drastic reductions in spending on mental health and shortages of medicines.6–9

Research suggesting adverse health consequences from the economic crisis in Greece has been criticised on a variety of grounds.10 11 One is the problem of attributing the findings definitively to the crisis, although, throughout this time, leading journalists were cataloguing problems being faced by those living in Greece, with accounts that bore out the story being told by the data.12 13 Another concern relates to the quality of data. However, a detailed examination of the quality of data on suicide assessed data from all 31 European Economic Area countries using the ratio of codes for suicide and undetermined cause (Tenth Revision International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes X60-X84 and Y10-Y34, respectively), concluding that Greece was 1 of only 12 countries to meet the quality benchmark.14 The process of death registration in Greece is similar to that in other European countries. A certificate of the fact and cause of death must be issued by a doctor. The death must then be registered, using the deceased’s identification papers and the medical death certificate, at the local Civil Registration Office (Ληξιαρχείο) within 3 days, when a civil registry death certificate is issued following review by the local Examining Magistrate. Where there are no unusual circumstances, the family is given permission for burial. However, if the Examining Magistrate is not satisfied, an autopsy may be required, along with further investigations and interviews with witnesses.

A recent extensive review of the deteriorating health situation in Greece argued that the dismissal of the available research met the criteria for denialism.15

The controversy about suicides has arguably been surprising, given the large body of evidence, both from previous economic crises and from other countries during the current crisis, suggesting that an increase would be expected in a country facing problems on the scale of those in Greece. Yet it is possible that Greece is in some way different. Unfortunately, there is a considerable time lag in obtaining mortality data and the most up-to-date published analysis only includes official data for 2010 and unofficial estimates for 2011,8 although the first austerity package was implemented in the final months of 2010. However, preliminary reports suggest that there has been an increase in absolute numbers of suicides and suicide rates in Greece during the economic crisis.15 In this study, we analyse more recent data, examining who has been most affected and the association with economic and labour market indicators.

Methods

We calculated the age-specific suicide rate, defined as suicide or self-inflicted injury or poisoning (ICD-9 E950-958) in Greece for the period 2003–2012 based on data provided by the Hellenic Statistical Authority. Since the first austerity measures were implemented in the final months of 2010, we compared the suicide rates in the preausterity period of 2003–2010 to the rate in 2011–2012.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney test was used for the comparison of suicide rates. Three age groups were examined, corresponding approximately to participation in the labour force in Greece (0–19; 20–59, ≥60 years). Unemployment and GDP data for the same period were obtained from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Stat Extracts. The Greek unemployment data are derived from the Quarterly Labour Force Survey which, consistent with practice throughout the OECD, defines unemployment as persons aged 15 to 74 years who (1) were seeking employment either as employees or as self-employed, during the previous 4 weeks preceding the reference week, (2) were available to start working within the 2 weeks, if work was found, and (3) had taken active steps in a specific recent period to seek employment (ie, applied to employers, asked friends or relatives, or inserted or answered advertisements in newspapers, etc.). Persons not working but who had already found a job, which will start later, that is, within a period of at most 3 months, are considered as unemployed.16

This analysis focused on men and women of working age (15–64 years). Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were used to assess any relationship between suicide rates, unemployment and GDP (2003–2012).These statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.21.0 software. In addition, to quantify the unemployment-suicide association, we performed pre/postcomparison, adjusting for time trends using regression discontinuity analysis in STATA).

Results

Trends in Greek suicides by period, age and sex

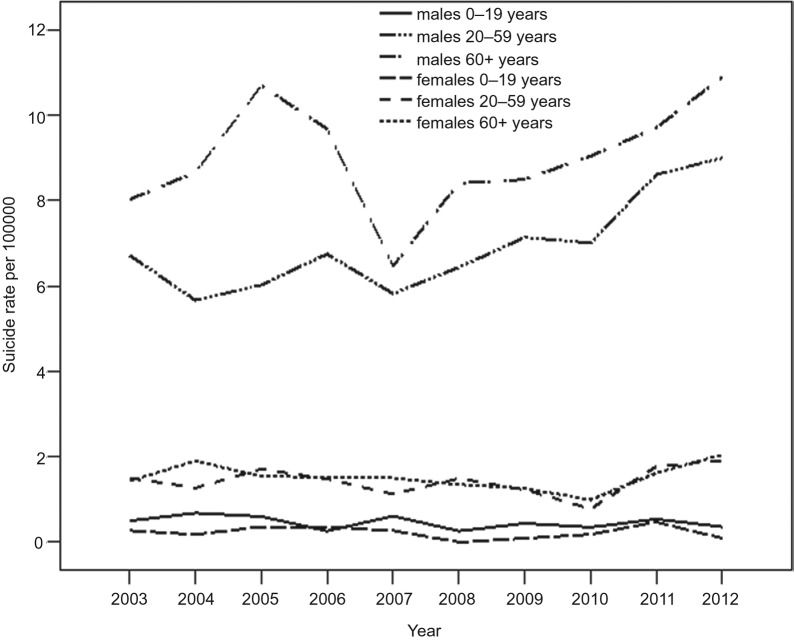

The suicide rate overall rose by 35% between 2010 and 2012, from 3.37 to 4.56/100 000 population (table 1). Figure 1 shows trends by sex and age group. In all age groups, suicides are consistently higher among men than women. There was a clear change in suicide trends after 2010 for both men and women of working age and older women. The situation for older men is less obvious, given the major fluctuations earlier in the decade. By 2012, rates for the two older groups, and for both sexes, were at their highest values for a decade.

Table 1.

Unemployment, GDP and suicides in Greece (2003–2012)

| Year | Unemployment (%) | GDP per capita (US$) | Suicide rate/ 100 000 | Suicides (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 9.7 | 17 494.40 | 3.40 | 375 |

| 2004 | 10.5 | 20 607.20 | 3.19 | 353 |

| 2005 | 9.9 | 21 620.70 | 3.60 | 400 |

| 2006 | 8.9 | 23 475.30 | 3.61 | 402 |

| 2007 | 8.3 | 27 288.30 | 2.93 | 328 |

| 2008 | 7.6 | 30 398.80 | 3.32 | 373 |

| 2009 | 9.5 | 28 451.90 | 3.47 | 391 |

| 2010 | 12.5 | 25 850.50 | 3.37 | 377 |

| 2011 | 17.7 | 25 630.80 | 4.28 | 477 |

| 2012 | 24.2 | 22 082.90 | 4.56 | 508 |

GDP, Gross Domestic Product.

Figure 1.

Suicide rates by sex and age group in Greece (2003–2012).

We then disaggregated suicide rates into the periods before and during Greece's austerity programme by age and sex. The mean suicide rate in Greece after 2010, when austerity began, was significantly higher than in the period 2003–2010 (4.42 vs 3.35/100 000 population, p<0.01). Rates increased significantly in both sexes. In particular, the suicide mortality rate for men increased from 5.75 (period 2003–2010) to 7.43/100 000 population (period 2011–2012; p<0.01). Among women, the suicide rate increased from 1.17 to 1.55, p=0.03.

The most affected age group was working men aged 20–59, in whom the suicide rate increased from 6.58 to 8.81/100 000 population (p<0.01). Among men aged >60, the suicide mortality rate increased from 8.58 (2003–2010) to 10.3 in 2011–2012, but this was not significant (p=0.053). By contrast, the suicide rate for men at ages 0–19 was stable at 0. 47 (2003–2010) and 0.45 (2011–2012). Among women at ages 20–59, we noted a significant increase in suicide mortality rate. In particular, the rate increased from 1.37 (2003–2010) to 1.84 (p=0.048). The suicide rate among older women (≥60) increased, again not statistically significantly, from 1.46 (2003–2010) to 1.83 (2011–2012). This was also observed for the age group 0–19 years.

Determinants of Greek suicide rates

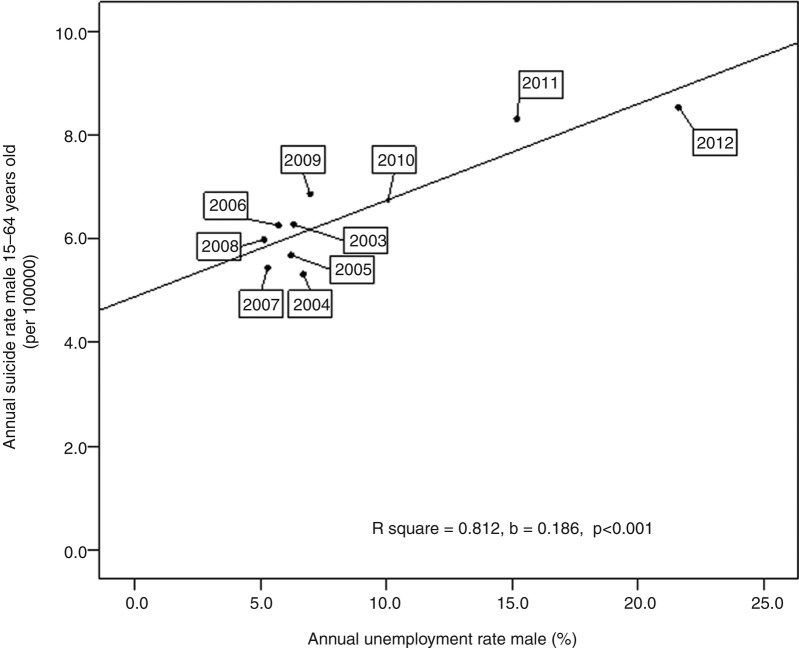

As shown in figure 2, we observed a significant association of male unemployment rates and suicide mortality among working age men 15–64 years (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.84, p<0.001) but not of female unemployment with suicides among women (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.56; p=0.09). There was no association between suicides in working age men or women and GDP.

Figure 2.

Suicide rate and unemployment among men aged 15–64 years in Greece (2003–2012).

To quantify the unemployment-suicide association (table 2), we observed that each 1 percentage point rise of unemployment rates in men aged 20–59 was associated with a 0.19/100 000 population rise in suicides (95% CI 0.11 to 0.26). Inclusion of unemployment as a dummy variable rendered the association with the austerity period insignificant (p=0.33), consistent with the possibility that unemployment was a significant mediating factor. On the basis of the observed 12 percentage point rise in unemployment during the austerity period, our statistical models estimate a 2.23/100 000 population rise attributable to job loss linked to austerity (95% CI 1.37 to 3.10), which largely accounts for the overall suicide increase in working-age men during this period.

Table 2.

Association of a 1 percentage point higher unemployment rate with suicide risk, per 100 000 population, by sex, 2003–2012

| Age group | Male unemployment | 95% CI | Female unemployment | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–19 | −0.004 | −0.03 to 0.02 | 0.02* | 0.004 to 0.04 |

| 20–59 | 0.19*** | 0.11 to 0.26 | 0.04 | −0.008 to 0.08 |

| 60+ | 0.14 | −0.02 to 0.30 | 0.04* | 0.0007 to 0.08 |

*p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

Discussion

The continuing delays in publishing mortality data mean that it will not, in the foreseeable future, be possible to bring the story of the economic crisis and suicide completely up to date, a failing that has important policy implications as it means that the Greek government and its creditors will inevitably prioritise measures to restructure the economy over those that might protect health.16 The disregard of health consequences of austerity was aided by the controversy over what the early data were saying, with known weaknesses in the data making it easy to dismiss any suggestion of emerging problems. However, with the data now available, it is possible to resolve the earlier controversy. There has been a clear increase in suicides among those of working age and older that coincides with the imposition of austerity, taking rates to levels not seen for a decade.

It is never possible, with an observational study, to establish causality. However, faced with the challenge of establishing the likelihood of a causal link between smoking and lung cancer, Bradford Hill established a set of criteria which, if met, made it more likely that an observed association is causal.17 Thus, the association is relatively strong, with a 34% increase in suicides among working age men. Our findings are consistent with what has been observed during the current crisis in almost all European countries, many of which actually saw a reversal of a long-term decline in suicides,18 19 and in the USA where a long-term upward trend accelerated.20 They are also consistent with research by other groups that has reported increases in suicidal ideation in Greece associated with austerity.21 22 The relationship is relatively specific, as death rates from many other causes have not increased and the effect is greatest in working age men, who were most affected by unemployment. The criterion of temporality is met, as the changes coincide with austerity, as expected. Given the data used, which precludes assessment of individual exposure to austerity, it is not possible to ascertain the presence of a biological gradient. The association is highly plausible, given the well-established association between economic shocks and suicide seen in many countries,23–25 and we examine this in more detail below. In this case, there is no meaningful way to examine coherence of epidemiological and laboratory findings or to undertake experiments. The criterion of analogy is met in that economic shocks have been shown, in the current crisis, to be associated not only with suicides but also a range of psychiatric disorders.26 Thus, to the extent that Bradford Hill's criteria apply to the observed association, they are consistent with a causal association.

Our analysis provides preliminary evidence that increased suicide mortality in Greece is a health hazard associated with radical austerity, although there are several possible mechanisms by which austerity may act. Thus, further research is needed to disentangle the mechanisms involved. One plausible mechanism is that austerity heightens suicide risks directly, by creating job losses, especially among public sector workers, and by increasing economic insecurity. This rise in what has been described as ‘economic suicides’27 could reflect an acute response of the Greek population to the rapid and dramatic changes of socioeconomic conditions induced by austerity programmes. As noted above, consistent with prior studies, our study found that risks were concentrated in working age men. This finding recalls how a 39% increase was observed between 1989 and 1994 in Russian men during the implementation of the ‘shock therapy’ programmes, which similarly resulted in considerable increases in unemployment and economic suffering.28 In addition, recent epidemiological data from another South European country, Spain, described an 8% increase in the suicide rate associated with economic crisis,29 at a time when unemployment rose from 8% to 24%. Another possible mechanism that may exacerbate the situation is the reduction in the Greek health budget, with cuts to services.6 Research undertaken before the current crisis showed an association between regional variations in suicide in Greece and provision of mental health services.30

What are the implications for policy? First, these findings strengthen further the argument for undertaking a comprehensive health impact assessment of the austerity being imposed by the troika, consistent with the obligation under the European Treaties.31 Second, when faced with an economic crisis, there are choices as to how to respond. In the current crisis, European countries have responded quite differently.32 However, in some cases, including Greece, it is not the elected government that has decided the response but rather external actors that have imposed it.

Crucially, historical evidence shows that increases in suicides during hard economic times are not inevitable. Some countries have been able to break the link between suicide and job loss by establishing active labour market programmes, whereby those losing jobs are given hope, with opportunities such as retraining exchange of information, and support for those with disabilities.33 In particular, between 1990 and 1993, Finland experienced a fivefold increase in unemployment, from 3.2% to 16.6%, during which period suicide rates dropped steadily. A similar pattern of decreased suicide mortality has been observed in Sweden during 1991–1992.33 Both countries implemented active labour market programmes during economic downturns to help newly unemployed persons quickly find jobs. Thus, just as can be seen in the historical responses to other crises, such as famines in Ireland or Bengal, policies adopted by the authorities can mitigate the consequences of the crisis or exacerbate them.34 Unfortunately, during the present crisis in Europe, the latter seems to have prevailed.

Our study has some inevitable limitations. There is no source of individual level data that would allow us to examine this issue, so we could only use aggregate data. We were unable to examine mediating factors other than job loss, such as homelessness and personal debt, even though we expect, on the basis of data from other countries, that these will have an effect.25 26 The number of observations is small, which is an inevitable consequence of using annual data to examine an acute event. Finally, although as noted in the introduction that the quality of suicide data from Greece is believed to be better than in many other European countries, we cannot exclude the possibility of changes in recording during this period, such as an increased focus on suicide as a cause of death during a period of austerity. However, this would not apply to other deaths that have increased at the same time, such as infant mortality.35

Our study does, however, have some advantages. First, it includes official data for the years 2011 and 2012 and permits a preliminary assessment of the effect of radical austerity on suicide rates. Second, we provided a quantitative assessment of the possible impact of unemployment increase on suicide in Greece.

In conclusion, our study revealed increased suicide mortality during the Greek economic crisis, and also that unemployment was significantly correlated with suicide mortality, especially among working age men. Finally, despite the fact that suicide rate is a sensitive indicator of the health impact of economic crisis, other possible health hazards of economic crisis in Greece should be also investigated.

Footnotes

Contributors: GR collected the data and participated in statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript. DS participated in study design, statistical analysis and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. MM participated in study design, as well as the drafting and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. CH participated in study design, data analysis and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: DS is funded by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data on age-specific and sex-specific suicide rates are available by emailing GR.

References

- 1.Rauch B, Göttsche M, Brähler G et al. . Fact and fiction in EU-governmental economic data. German Econ Rev 2011;12:243–55. 10.1111/j.1468-0475.2011.00542.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hope K. Grim effects of austerity show on Greek streets. Financial Times 17 February 2012.

- 3.Henley J. Greece on the breadline: how leftovers became a meal. Guardian 14 March 2012.

- 4.Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I et al. . Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011;378:1457–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61556-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Economou M, Madianos M, Theleritis C et al. . Increased suicidality amid economic crisis in Greece. Lancet 2011;378:1459 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61638-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kentikelenis A, Papanicolas I. Economic crisis, austerity and the Greek public health system. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:4–5. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karamanoli E. Greece's financial crisis dries up drug supply. Lancet 2012;379:302 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60129-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0265-4. Antonakakis N, Collins A. The impact of fiscal austerity on suicide: on the empirics of a modern Greek tragedy. Soc Sci Med 2014;112:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rachiotis G, Kourousis C, Kamilaraki M et al. . Medical supplies shortages and burnout among Greek Health Care workers during economic crisis: a pilot study. Int J Med Sci 2014;11:442–7. 10.7150/ijms.7933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liaropoulos L. Greek economic crisis: not a tragedy for health. BMJ 2012;345:e7988–8. 10.1136/bmj.e7988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polyzos N. Health and the financial crisis in Greece. Lancet 2012;379:1000 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60421-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelland K. Basic hygiene at risk in debt-stricken Greek hospitals. Reuters 2012. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2012/12/04/us-greece-austerity-disease-idUSBRE8B30NR20121204 (accessed 5 May 2014).

- 13.Daley S. Greeks reeling from health care cutbacks. The New York Times 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/27/world/europe/greeks-reeling-from-health-care-cutbacks.html (accessed 5 May 2014).

- 14.Varnik P, Sisask M, Varnik A et al. . Validity of suicide statistics in Europe in relation to undetermined deaths: developing the 2–20 benchmark. Inj Prev 2012;18:321–5. 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Reeves A et al. . Greece's health crisis: from austerity to denialism. Lancet 2014;383:748–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62291-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.OECD. Main economic indicators. Paris, 2014. http://stats.oecd.org/mei/default.asp?lang=e&subject=10&country=GRC [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A et al. . Suicides associated with the 2008–10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e5142 10.1136/bmj.e5142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Economic suicides in the Great Recession in Europe and North America. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:246–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves A, Stuckler D, McKee M et al. . Increase in state suicide rates in the USA during economic recession. Lancet 2012;380:1813–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61910-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Economou M, Madianos M, Peppou LE et al. . Suicidality and the economic crisis in Greece. Lancet 2012;380:337; author reply 37–8 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61244-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Economou M, Madianos M, Peppou LE et al. . Suicidal ideation and reported suicide attempts in Greece during the economic crisis. World Psychiatry 2013;12:53–9. 10.1002/wps.20016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maki N, Martikainen P. A register-based study on excess suicide mortality among unemployed men and women during different levels of unemployment in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:302–7. 10.1136/jech.2009.105908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milner A, Morrell S, LaMontagne AD. Economically inactive, unemployed and employed suicides in Australia by age and sex over a 10-year period: what was the impact of the 2007 economic recession? Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1500–7. 10.1093/ije/dyu148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coope C, Gunnell D, Hollingworth W et al. . Suicide and the 2008 economic recession: who is most at risk? Trends in suicide rates in England and Wales 2001–2011. Soc Sci Med 2014;117: 76–85. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gili M, Roca M, Basu S et al. . The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:103–8. 10.1093/eurpub/cks035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves A, McKee M, Gunnell D et al. . Economic shocks, resilience, and male suicides in the Great Recession: cross-national analysis of 20 EU countries. Eur J Public Health 2014. [Epub ahead of print 6 Oct 2014]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walberg P, McKee M, Shkolnikov V et al. . Economic change, crime, and mortality crisis in Russia: regional analysis. BMJ 1998;317:312–18. 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez Bernal JA, Gasparrini A, Artundo CM et al. . The effect of the late 2000s financial crisis on suicides in Spain: an interrupted time-series analysis. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:732–6. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giotakos O, Tsouvelas G, Kontaxakis V. [Suicide rates and mental health services in Greece]. Psychiatriki 2012;23:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKee M, Karanikolos M, Belcher P et al. . Austerity: a failed experiment on the people of Europe. Clin Med 2012;12:346–50. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-4-346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves A, Basu S, McKee M et al. . The political economy of austerity and healthcare: Cross-national analysis of expenditure changes in 27 European nations 1995–2011. Health Policy 2014;115:1–8. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M et al. . The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 2009;374:315–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sen A. Poverty and famines: an essay on entitlement and deprivation. Reprint with corrections. Oxford: Clarendon, 1981, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajmil L, Fernandez de Sanmamed MJ, Choonara I et al. . Impact of the 2008 economic and financial crisis on child health: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:6528–46. 10.3390/ijerph110606528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]