Significance

Many free-living and parasitic nematode (roundworm) species use pheromones called ascarosides to control their development and behavior. The molecular mechanisms by which environmental factors influence pheromone composition are unknown. The side chains of the ascarosides are derived from long-chain fatty acids that are shortened through β-oxidation cycles. In this manuscript, we show that three acyl-CoA oxidases, which catalyze the first step in the β-oxidation cycles, form specific homo- and heterodimers with different side-chain length preferences. Stressful conditions induce the expression of specific acyl-CoA oxidases, resulting in corresponding changes in pheromone composition. Thus, our work demonstrates how environmental conditions can influence the chemical message that nematodes communicate to other roundworms in the population.

Keywords: dauer, pheromone, ascaroside, beta-oxidation, acyl-CoA oxidase

Abstract

Caenorhabditis elegans uses ascaroside pheromones to induce development of the stress-resistant dauer larval stage and to coordinate various behaviors. Peroxisomal β-oxidation cycles are required for the biosynthesis of the fatty acid-derived side chains of the ascarosides. Here we show that three acyl-CoA oxidases, which catalyze the first step in these β-oxidation cycles, form different protein homo- and heterodimers with distinct substrate preferences. Mutations in the acyl-CoA oxidase genes acox-1, -2, and -3 led to specific defects in ascaroside production. When the acyl-CoA oxidases were expressed alone or in pairs and purified, the resulting acyl-CoA oxidase homo- and heterodimers displayed different side-chain length preferences in an in vitro activity assay. Specifically, an ACOX-1 homodimer controls the production of ascarosides with side chains with nine or fewer carbons, an ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer controls the production of those with side chains with seven or fewer carbons, and an ACOX-2 homodimer controls the production of those with ω-side chains with less than five carbons. Our results support a biosynthetic model in which β-oxidation enzymes act directly on the CoA-thioesters of ascaroside biosynthetic precursors. Furthermore, we identify environmental conditions, including high temperature and low food availability, that induce the expression of acox-2 and/or acox-3 and lead to corresponding changes in ascaroside production. Thus, our work uncovers an important mechanism by which C. elegans increases the production of the most potent dauer pheromones, those with the shortest side chains, under specific environmental conditions.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans secretes the ascarosides, structurally diverse derivatives of the 3,6-dideoxy-l-sugar ascarylose, as chemical signals to control its development and behavior. Under favorable growth conditions, C. elegans progresses from the egg through four larval stages (L1–L4) to the reproductive adult. At high nematode population densities, however, specific ascarosides, which are together known as the dauer pheromone, trigger entry into a specialized L3 larval stage called the dauer (Fig. 1A) (1–5). Dauers have a thickened cuticle, do not feed, derive energy from fat stores, and up-regulate stress-resistance pathways (6). Certain ascarosides also influence behaviors, including male attraction to hermaphrodites, hermaphrodite attraction to males, avoidance, and aggregation (7–12). C. elegans senses the ascarosides using several classes of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are expressed in specific chemosensory neurons (13, 14). The dauer pheromone ascarosides induce dauer formation by downregulating the insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and TGF-β pathways, which control not only dauer development but also metabolism and lifespan in C. elegans (15).

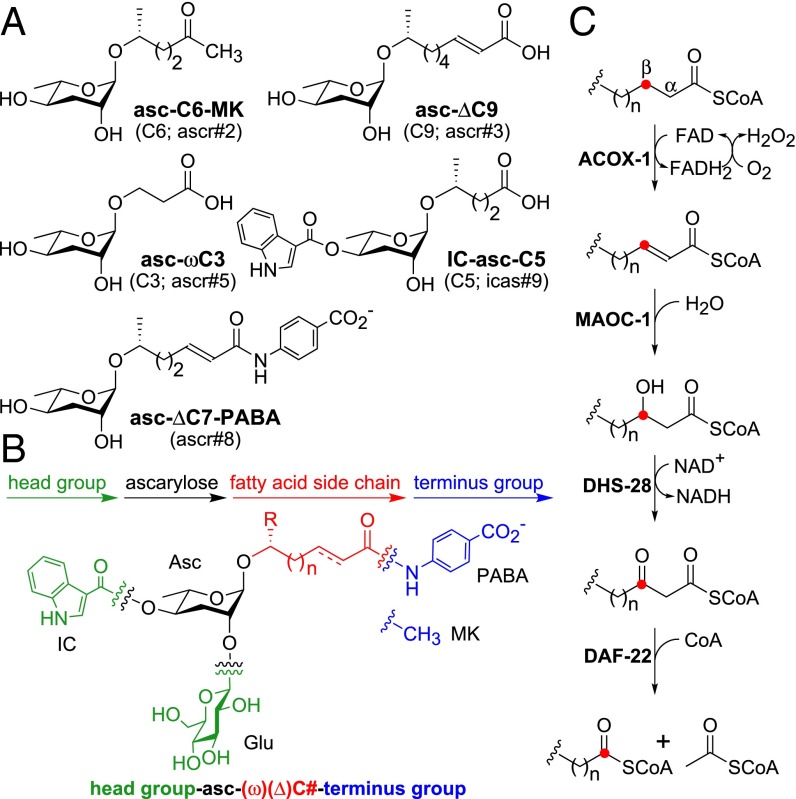

Fig. 1.

Ascaroside pheromones and β-oxidation enzymes implicated in their biosynthesis. (A) Dauer-inducing ascaroside pheromones. (B) Modular structure of the ascarosides. The ascarosides can be named according to the number of carbons in their side chains using the following rubric: head group-asc-(ω)(Δ)C#-terminus group. Head groups can be attached via the 4′-hydroxyl of ascarylose (e.g., indole-3-carbonyl group) or the 2′-hydroxyl of ascarylose (e.g., glucosyl group). Modifications to the terminus of the side chain include para-aminobenzoic acid and methylketone. R = H for the ω-ascarosides and R = CH3 for the (ω-1)-ascarosides. (C) The β-oxidation enzymes implicated in ascaroside biosynthesis. The red dot tracks the position of the β-carbon during the β-oxidation cycle.

All ascarosides have a simple, modular structure with a fatty acid-derived side chain (Fig. 1B). The fatty acid side chain is attached to the ascarylose sugar at either its penultimate (ω-1) or terminal (ω) carbon, and is sometimes unsaturated (Δ) at the α-β position. The ascarosides can be named according to the number of carbons in their side chains using the following rubric: head group-asc-(ω)(Δ)C#-terminus group (16). Head groups attached to the ascarylose sugar include the indole-3-carbonyl (IC) and glucosyl (Glu) modifications, and terminus groups on the fatty acid terminus include the methylketone (MK) and para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) modifications (Fig. 1B). The dauer pheromone consists of at least five ascarosides, asc-C6-MK (C6; ascr#2), asc-ΔC9 (C9; ascr#3), asc-ωC3 (C3; ascr#5), IC-asc-C5 (C5; icas#9), and asc-ΔC7-PABA (ascr#8) (Fig. 1A) (2–5). Of the dauer pheromone ascarosides, only asc-ωC3 has a side chain that is attached to the ascarylose sugar at its ω-carbon [as opposed to its (ω-1)-carbon]. Intriguingly, this ascaroside works synergistically with the others to induce dauer formation (3), and targets a unique class of GPCRs (13, 14).

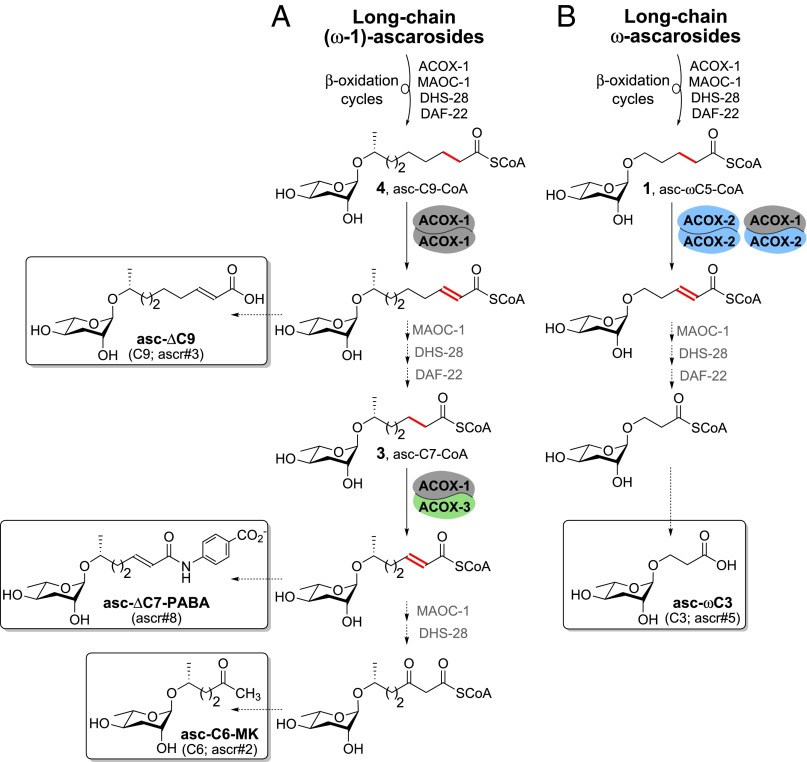

Biosynthesis of the side chains of the ascarosides requires peroxisomal β-oxidation cycles that shorten the side chains by two carbons per cycle (11, 17–19). Four peroxisomal enzymes, an acyl-CoA oxidase (ACOX-1), enoyl-CoA hydratase (MAOC-1), (3R)-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (DHS-28), and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (DAF-22), have been implicated in the β-oxidation cycles for ascaroside biosynthesis (Fig. 1C) (11, 17–19). These enzymes are homologous to mammalian peroxisomal enzymes that process very long chain fatty acids, branched-chain fatty acids, and bile acid intermediates (20). Worms with mutations in maoc-1, dhs-28, or daf-22 do not produce any of the short-chain, dauer-inducing ascarosides, but instead accumulate ascarosides with long-chain side chains, stalled at different steps in the β-oxidation process (11, 17). This phenotype suggests the following three models for the role of β-oxidation in ascaroside biosynthesis: (i) β-Oxidation shortens long-chain ω/(ω-1)-ascarosides to short-chain ω/(ω-1)-ascarosides; (ii) β-oxidation shortens long-chain ω/(ω-1)-hydroxylated fatty acids to short-chain ω/(ω-1)-hydroxylated fatty acids, which are then attached to the ascarylose sugar; or (iii) β-oxidation shortens long-chain fatty acids to short-chain fatty acids, which are then ω/(ω-1)-hydroxylated and attached to the ascarylose sugar (Fig. S1). Worms with mutations in acox-1 have a less severe phenotype; they produce very little asc-ωC3, asc-C5, asc-ΔC7, and asc-ΔC9 and, instead, accumulate asc-ωC5 and asc-C9, implicating ACOX-1 in the β-oxidation of both ω- and (ω-1)-ascarosides (11). This result suggests that fatty acid side-chain hydroxylation precedes β-oxidation during the biosynthetic process and that the third model is not correct.

Ascaroside production has been shown to be influenced by a variety of factors, including developmental stage (21), temperature (3, 19), and sex (8), although interpretation of these results is often complicated by the fact that they were obtained by changing multiple variables at the same time (21) or by using long-term, mixed-larval stage cultures (3, 19). Starvation has been suggested to increase the ratio of asc-ΔC9 to asc-ωC3 in long-term, mixed-stage cultures (11). On the other hand, starved L1 larvae, in comparison with those that are fed, have been shown to secrete a higher ratio of ascarosides with shorter, 5-carbon side chains to those with longer, 9-carbon side chains (12).

Here we show that specific acyl-CoA oxidases enable C. elegans to modulate the composition of the ascaroside pheromones that it produces under different environmental conditions. Specifically, an ACOX-1 homodimer acts on the CoA-thioester of an ascaroside with a 9-carbon (ω-1)-side chain, an ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer acts on one with a 7-carbon (ω-1)-side chain, and an ACOX-2 homodimer acts on one with a 5-carbon ω-side chain. Using quantitative (q)RT-PCR, we show that acox-2 and acox-3, which act as gatekeepers for the production of shorter-chain ascarosides, are regulated by changes in temperature and food availability, leading to corresponding changes in ascaroside production. Studies of the ascaroside biosynthetic pathway and how it is modulated by different factors to control pheromone production will shed light on chemical communication in the C. elegans model system, as well as in other free-living and parasitic nematode species, which also use ascarosides as pheromones (22, 23).

Results

Role of the ACOX-1 Homodimer in Ascaroside Biosynthesis.

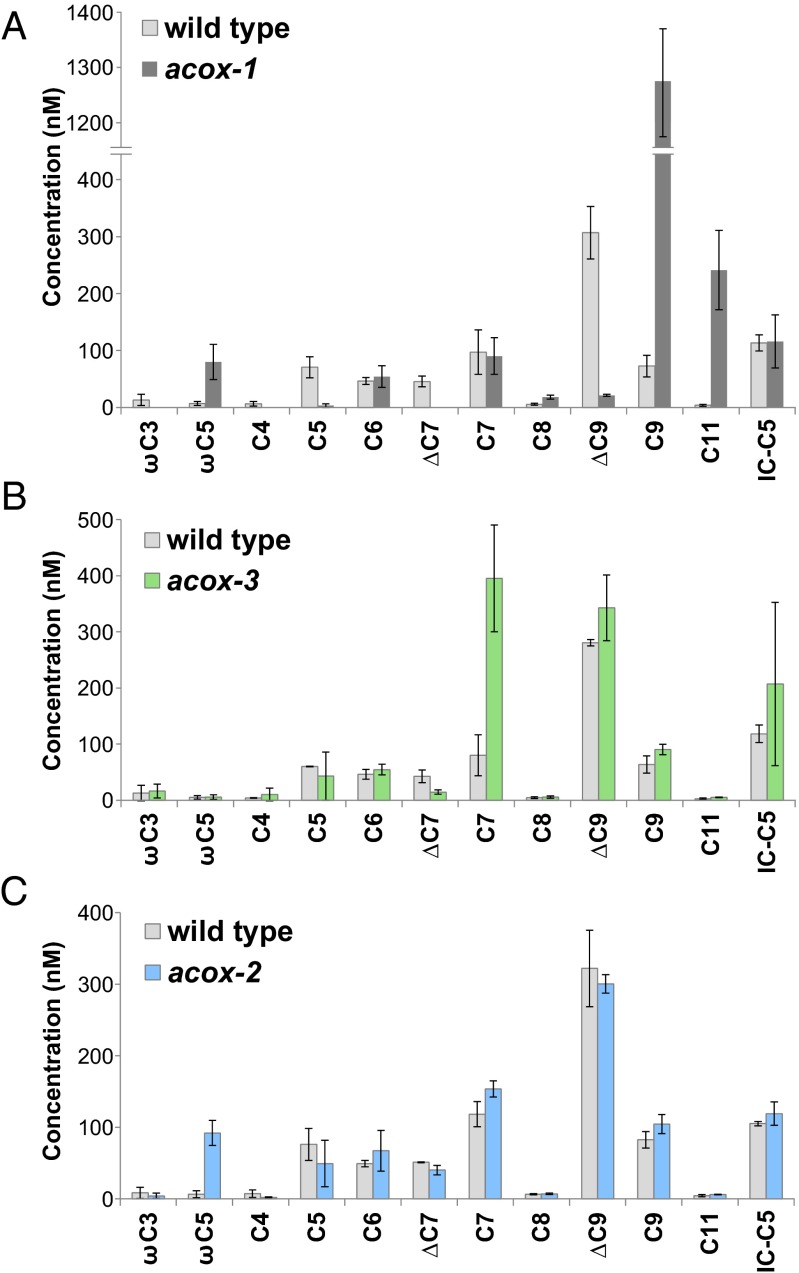

BLAST analysis of ACOX-1 indicated the existence of several homologs in C. elegans (Fig. S2). To characterize the role of acyl-CoA oxidases in ascaroside production, we cultivated mixed-stage cultures of wild-type (N2) worms, available deletion mutants of acox-1 and acox-3 (F08A8.3), as well as a recently isolated acox-2 (F08A8.2) nonsense mutant (24). The ascarosides secreted by these mutants were then analyzed by LC-MS/MS in precursor scanning mode, monitoring for the product ion m/z 73.0 (11, 16). The mutants displayed distinct defects in ascaroside biosynthesis (Fig. 2). Similar to as shown by von Reuss et al. (11), the acox-1 mutant produces an increased amount of asc-C9 and a reduced amount of asc-ΔC9 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that ACOX-1 is required in the first step of the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 9-carbon (ω-1)-side chain to a 7-carbon (ω-1)-side chain. The mutant produces a similar amount of asc-C7 as wild type but no asc-ΔC7 and very little asc-C5, suggesting that ACOX-1 is required for the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 7-carbon (ω-1)-side chain to a 5-carbon (ω-1)-side chain. The mutant produces an increased amount of asc-ωC5 and virtually no asc-ωC3, suggesting that ACOX-1 is also required in the cycle that processes a 5-carbon ω-side chain to a 3-carbon ω-side chain. In addition, the acox-1 mutant produces a reduced amount of asc-C6-MK, as determined by LC-MS (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

LC-MS/MS analysis of the ascarosides produced by acyl-CoA oxidase mutants. The ascarosides produced by the acox-1 deletion mutant (A), acox-3 deletion mutant (B), and acox-2 nonsense mutant (C). Data represent the average of at least two experiments ± SD.

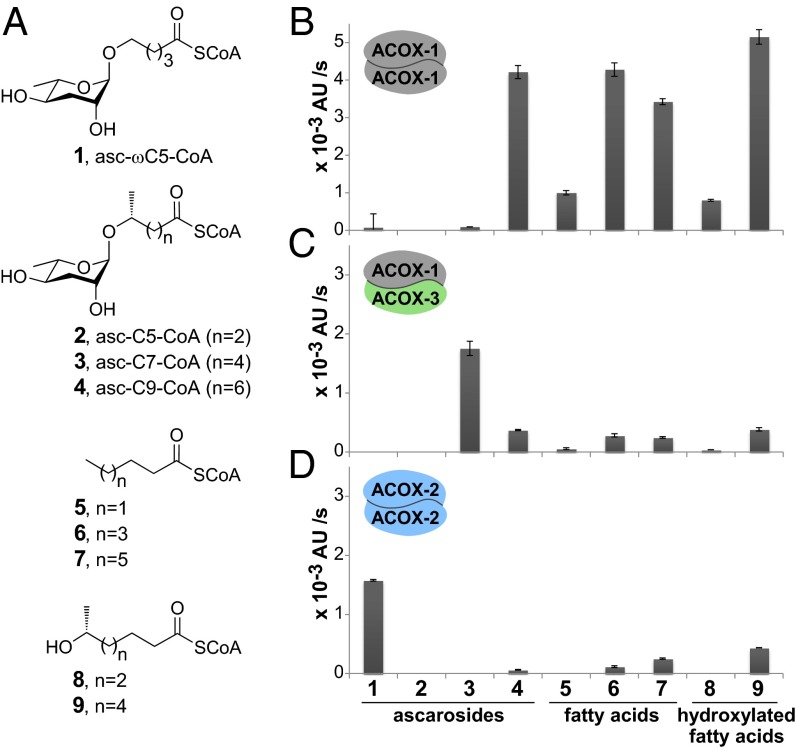

To investigate further the role of acox-1, we cloned the gene from a cDNA library, expressed it in Escherichia coli, and purified the protein for in vitro assays against synthetic substrates. Based on its retention time on a gel filtration column relative to protein standards, ACOX-1 was expressed as a homodimer. As the type(s) of substrates used by ACOX-1 has not been established, we synthesized CoA-thioesters of ascarosides (1–4), fatty acids (5–7), and hydroxylated fatty acids (8 and 9) of various carbon chain lengths (Fig. 3A). The CoA-thioesters of the ascarosides could be made by directly coupling the carboxylic acids of unprotected ascarosides with CoA with yields of 10–40%. The acyl-CoA oxidase activity of ACOX-1 against the different substrates was determined by monitoring H2O2 production using a coupled reaction catalyzed by peroxidase that generates a UV-active product (25). ACOX-1 demonstrated a broad substrate range against the CoA-thioesters of fatty acids and hydroxylated fatty acids (Fig. 3B), consistent with a general role for acox-1 in peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation. In terms of ascaroside substrates, ACOX-1 was specifically active toward asc-C9-CoA (4) (Fig. 3B). The kcat and Km of ACOX-1 against asc-C9-CoA (4) were of a similar order as those of mammalian acyl-CoA oxidases against fatty acyl-CoA substrates (26) (Table S1). Surprisingly, however, ACOX-1 was not active against any other ascaroside-based substrates, including asc-ωC5-CoA (1) or asc-C7-CoA (3), contrary to what might be expected from the LC-MS/MS data of the acox-1 mutant (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 3.

In vitro activity of acyl-CoA oxidase homo- and heterodimers. (A) Synthetic substrates, including CoA-thioesters of ascarosides, fatty acids, and hydroxylated fatty acids. (B–D) Activity of the ACOX-1 homodimer (B), ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer (C), and ACOX-2 homodimer (D) against the substrates, tested at 30 μM. Data represent the average of three experiments ± SD. AU, absorbance units.

Role of the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 Heterodimer in Ascaroside Biosynthesis.

In comparison with wild-type worms, the acox-3 deletion mutant produces an increased amount of asc-C7 and a reduced amount of asc-ΔC7 (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that ACOX-3 is involved in the first step of the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 7-carbon (ω-1)-side chain to a 5-carbon (ω-1)-side chain. The phenotype of the acox-3 mutant, however, is more subtle than that of the acox-1 mutant (compare Fig. 2 A and B), suggesting that ACOX-3 is not solely responsible for this step.

To investigate further the role of acox-3, we cloned the gene from a cDNA library and attempted to express it in E. coli to purify the protein for in vitro activity assays. However, we were not able to overexpress ACOX-3 in either a soluble or insoluble form, even after synthesizing a codon-optimized version of the gene, cloning it into various expression plasmids with either an N- or a C-terminal His tag, and repeatedly attempting to optimize expression conditions. Because the LC-MS/MS data of the acox-1 mutant indicated that ACOX-1 is required for the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 7-carbon (ω-1)-side chain to a 5-carbon (ω-1)-side chain, we speculated that ACOX-1 and ACOX-3 may work together and that coexpression of ACOX-1 with ACOX-3 in E. coli may be required for the expression of ACOX-3. The acox-1 and acox-3 genes were cloned such that ACOX-1 would be expressed without a tag and ACOX-3 would be expressed with a His tag. This coexpression system enabled expression and purification of an ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer. The two proteins appeared on an SDS/polyacrylamide gel as two bands of slightly different apparent molecular weight in an approximate 1:1 ratio, and their identities were verified through tryptic digestion of the proteins and mass spectrometry of the fragments (Fig. S4 A and B). To confirm the identities of the two bands, the acox-1 and acox-3 genes were recloned such that ACOX-1 would be expressed with a FLAG tag and ACOX-3 would be expressed with a His tag. Western blot of the heterodimer supported the identification of the two bands as ACOX-1 and ACOX-3 (Fig. S4C). Thus, our results provide strong evidence that the expression and/or stability of ACOX-3 is dependent on the formation of a complex with ACOX-1.

The acyl-CoA oxidase activity of the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer was monitored against different substrates (Fig. 3 A and C). Remarkably, the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer was specifically active toward asc-C7-CoA (3) (Fig. 3C and Table S1). Unlike the ACOX-1 homodimer, the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer was not active against any fatty acid or hydroxylated fatty acid-type substrates. This substrate specificity provides the first, to our knowledge, direct evidence that the acyl-CoA oxidases and other enzymes involved in the β-oxidation cycles in the ascaroside biosynthetic pathway act directly on the CoA-thioesters of ascarosides, rather than on the CoA-thioesters of either fatty acids or hydroxylated fatty acids (that is, model 1 in Fig. S1). The substrate specificity of the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer is consistent with the LC-MS/MS ascaroside profiles of the acox-1 and acox-3 mutants, which both showed an increase in the ratio of asc-C7 to asc-ΔC7 relative to wild type. Thus, the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer plays a key role in the β-oxidation cycle that shortens a 7-carbon (ω-1)-ascaroside to a 5-carbon (ω-1)-ascaroside. Furthermore, both the acox-1 and acox-3 mutants show a reduced amount of asc-C6-MK as analyzed by LC-MS (Fig. S3). Thus, the biosynthesis of asc-C6-MK occurs downstream of the conversion of asc-C7-CoA (3) to asc-ΔC7-CoA catalyzed by the ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer.

Role of the ACOX-2 Homodimer and ACOX-1/ACOX-2 Heterodimer in Ascaroside Biosynthesis.

In comparison with wild-type worms, the acox-2 nonsense mutant produces an increased amount of asc-ωC5 and a reduced amount of asc-ωC3 (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that ACOX-2 plays a role in the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 5-carbon ω-side chain to a 3-carbon ω-side chain. To determine the substrate specificity of ACOX-2, we expressed ACOX-2 in E. coli and purified the protein for in vitro activity assays. The ACOX-2 homodimer was not active against any fatty acid or hydroxylated fatty acid-type substrates, but was active specifically toward asc-ωC5-CoA (1) (Fig. 3 A and D). Thus, the substrate specificity of the ACOX-2 homodimer is consistent with the LC-MS/MS ascaroside profile of the acox-2 mutant.

Because the LC-MS/MS data of the acox-1 mutant suggested that ACOX-1 plays a role in the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 5-carbon ω-side chain to a 3-carbon ω-side chain, we speculated that ACOX-1 might also form a heterodimer with ACOX-2. The acox-1 and acox-2 genes were cloned such that ACOX-1 would be expressed without a tag and ACOX-2 would be expressed with a His tag. This coexpression system suggested that ACOX-1 and ACOX-2 interact, as verified through tryptic digestion of the proteins and mass spectrometry of the fragments (Fig. S5 A and B). In terms of ascaroside substrates, the purified proteins were most active toward asc-ωC5-CoA (1) and showed a greater catalytic efficiency toward asc-ωC5-CoA (1) than did the ACOX-2 homodimer (Fig. 3D, Fig. S5C, and Table S1). To confirm the interaction between ACOX-1 and ACOX-2, the acox-1 and acox-2 genes were recloned such that ACOX-1 would be expressed with a FLAG tag and ACOX-2 would be expressed with a His tag. Western blot confirmed that ACOX-2 could pull down ACOX-1, although the protein purified is likely a mixture of ACOX-1/ACOX-2 heterodimers and ACOX-2 homodimers (Fig. S5D). Thus, an ACOX-2 homodimer, as well as possibly an ACOX-1/ACOX-2 heterodimer, plays an important role in the β-oxidation cycle that processes a 5-carbon ω-side chain to a 3-carbon ω-side chain to produce asc-ωC3.

Another possible explanation for the effect of the acox-1 deletion on asc-ωC3 biosynthesis is that the deletion influences the expression of acox-2, because the deletion is only 1.299 kb upstream of the start codon of acox-2. However, analysis of acox-2 expression in wild-type worms and in the acox-1 mutant using qRT-PCR showed that acox-2 expression is not strongly down-regulated in the mutant (Fig. S6). Thus, it is unlikely that the primary reason that the acox-1 mutant does not make any asc-ωC3 is simply because the deletion in this mutant interferes with acox-2 expression.

Effect of Environmental Conditions on Ascaroside Production and Acyl-CoA Oxidase Gene Expression.

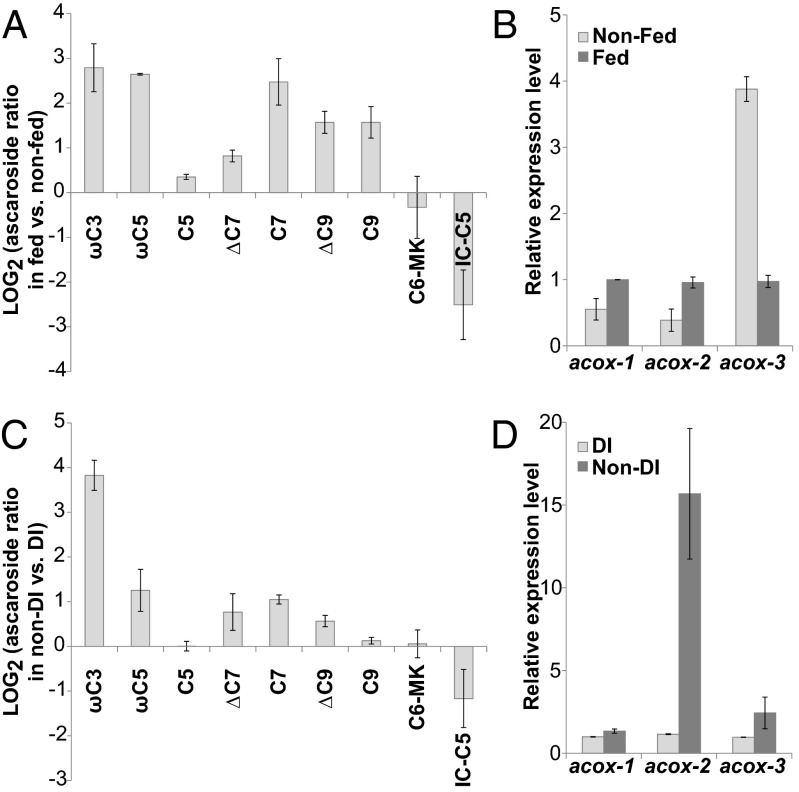

Our biochemical results suggested that ACOX-2 and ACOX-3 serve as specialized acyl-CoA oxidases that promote the biosynthesis of short-chain ω- and (ω-1)-ascarosides, respectively. Thus, we hypothesized that the expression of these proteins may be regulated by environmental conditions to enable the composition of the ascarosides produced by C. elegans to change in response to specific conditions, such as different temperatures and starvation. To investigate the effect of food availability, we grew synchronized cultures of wild-type worms to the L4 stage but gave the cultures minimal bacterial food (E. coli) such that once the worms reached the L4 stage, they were starving. At this point, the cultures were either fed or not fed additional bacterial food, and the culture medium and worms from the cultures were collected at 4 and 24 h. By performing this experiment over a relatively short period in synchronized adults, we attempted to minimize the indirect effect of food on ascaroside production due to the increased growth rate upon food addition. Acyl-CoA oxidase gene expression in the worms at 4 h was analyzed using qRT-PCR, and ascaroside secretion into the culture medium at 24 h was analyzed using LC-MS. Production of most ascarosides was increased in fed worms, as one might expect, because the fed worms presumably have a greater metabolic potential. However, production of shorter-chain (ω-1)-ascarosides, such as asc-ΔC7, asc-C5, and asc-C6-MK, was not increased in fed worms as much or not at all, and production of IC-asc-C5 was reduced (Fig. 4A). Correspondingly, the acox-3 gene was strongly down-regulated by food addition, suggesting a mechanism whereby the production of shorter-chain (ω-1)-ascarosides is suppressed by these conditions (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Ascaroside production (A and C) and expression levels of acyl-CoA oxidase genes (B and D) under different conditions. (A) Ratio of the ascarosides produced over a short time period (20 h) by fed versus nonfed L4 worms. (B) Expression of acox-1, -2, and -3 in fed versus nonfed L4 worms, 4 h after treatment. (C) Ratio of ascarosides produced by synchronized worms cultivated in non-DI versus DI conditions during the first 28 h of the time course (see Fig. S7 for the full dataset). (D) Expression of acox-1, -2, and -3 in synchronized worms cultivated in non-DI versus DI conditions at the 21-h time point. Data represent the average of two experiments ± SD.

To determine the effect of dauer-inducing (DI) conditions on ascaroside production and acyl-CoA oxidase gene expression in early larval stage worms, we monitored pheromone production in cultures initiated with synchronized L1 larvae under either DI (high population density and low food) or non-DI (low population density and high food) conditions (Fig. S7). Although pheromone levels were monitored from the L2 to young adult stages, it should be noted that worms grown under non-DI conditions have an increased growth rate relative to worms grown under DI conditions, presumably giving them greater capacity to produce pheromones, especially at later time points. Analysis of an early time point (28 h) indicates that non-DI conditions strongly induced the production of the short-chain ω-ascaroside asc-ωC3 (Fig. 4C). Consistent with increased asc-ωC3 production under non-DI conditions, the acox-2 gene was very strongly up-regulated under these conditions relative to DI conditions (Fig. 4D). Given that in our hands asc-ωC3 is the most robust dauer pheromone component (3), it was surprising that asc-ωC3 was produced in higher amounts under non-DI conditions because, in general, C. elegans would presumably not need to enter dauer under these conditions. However, we speculate that perhaps asc-ωC3 enables dauer formation in the face of specific stressors despite the presence of food or otherwise favorable conditions. Indeed, unlike other dauer pheromone components, asc-ωC3 induces dauer, even when the dauer formation assay is performed using live (antibiotic-treated) food, rather than heat-killed food (Fig. S8).

To investigate the effect of temperature on ascaroside production and acyl-CoA oxidase gene expression, we grew cultures of wild-type worms from eggs to the young adult stage at either 20 °C or 25 °C. Once the worms reached the young adult stage, they were grown for an additional 24 h at the different temperatures. The production of most ascarosides increased at the higher temperature (Fig. S9A). The expression of acox-2 and -3 also increased at the higher temperature (Fig. S9B). Increased ascaroside production may contribute to the increased dauer formation seen in C. elegans at higher temperatures.

Discussion

The ascarosides represent a nuanced chemical language that C. elegans and many other species of nematodes use in communication. Depending on its larval stage, larval history, sex, temperature, and nutritional environment, C. elegans produces a different mixture of ascarosides to communicate different information to other individuals in the population and to improve the survival of conspecifics. Here we have shown that C. elegans uses specific acyl-CoA oxidase complexes to control the production of the short-chain ascarosides. Importantly, we show that an ACOX-1/ACOX-3 heterodimer catalyzes the first step in the β-oxidation cycle that shortens an ascaroside with a 7-carbon (ω-1)-side chain to one with a 5-carbon (ω-1)-side chain (Fig. 5). Thus, ACOX-3 is important for the biosynthesis of the shorter-chain (ω-1)-ascarosides, including the dauer pheromone asc-C6-MK. An ACOX-2 homodimer, as well as possibly an ACOX-1/ACOX-2 heterodimer, catalyzes the first step in the β-oxidation cycle that shortens an ascaroside with a 5-carbon ω-side chain to one with a 3-carbon ω-side chain (Fig. 5). Thus, ACOX-2 is important for the biosynthesis of the short-chain ω-ascarosides, including the robust dauer pheromone asc-ωC3, which acts synergistically with other ascarosides to induce dauer (3).

Fig. 5.

Model for the role of specific acyl-CoA oxidase homo- and heterodimers in the biosynthetic pathway of (ω-1)-ascarosides (A) and ω-ascarosides (B). Dauer pheromone ascarosides are boxed. Dotted arrows and enzymes that appear in gray indicate hypothetical steps and activities that have not yet been verified experimentally.

Consistent with the role of ACOX-3 in the production of short-chain (ω-1)-ascarosides, the expression of acox-3 and the production of short-chain (ω-1)-ascarosides (e.g., asc-ΔC7, asc-C5, and asc-C6-MK) are both suppressed in synchronized L4 larvae upon the addition of bacterial food. Consistent with the role of ACOX-2 in the production of short-chain ω-ascarosides, the expression of acox-2 and the production of asc-ωC3 are both increased in early larval stage worms grown in non-DI conditions. Our results show that acox-2 and -3 are transcriptionally up-regulated in adult worms that have been grown at higher temperatures. These results agree with expression profiling experiments that showed that acox-2 and -3 are up-regulated by a shift to higher temperatures (27). Up-regulation of acyl-CoA oxidase genes may contribute to increased pheromone production at higher temperatures.

It is somewhat counterintuitive that production of asc-ωC3, a potent dauer pheromone, would be increased under non-DI conditions. Indeed, this ascaroside targets GPCRs in the ASI neuron, which plays a direct role in inducing dauer (14). Unlike several other dauer pheromone components, asc-ωC3 has a very sharp EC50 curve in the dauer formation assay and induces close to 90% dauers at higher concentrations (3). The EC50 of asc-ωC3 in the dauer formation assay is also similar at low and high temperatures (3, 4). Our results show that asc-ωC3 can induce dauer even in the presence of live (antibiotic-treated) bacteria. Thus, asc-ωC3 may enable dauer formation in response to certain stressors, even when conditions are otherwise favorable. Alternatively, it could be that asc-ωC3 has some biological activity or role that has yet to be identified. It is unknown whether asc-ωC3 production in non-DI conditions is a response to specific nutrients in the bacteria, the slight pathogenicity of E. coli (28), or other factors.

In mammals, the first step in peroxisomal β-oxidation is catalyzed by several acyl-CoA oxidases with different substrate preferences (20). Palmitoyl-CoA oxidase is specific to the CoA-thioesters of straight-chain fatty acids, pristanoyl-CoA oxidase is specific to the CoA-thioesters of 2-methyl-branched-chain fatty acids and long/very long straight-chain fatty acids, and cholestanoyl-CoA oxidase is specific to the CoA-thioesters of bile acids. Whereas palmitoyl-CoA oxidase and cholestanoyl-CoA oxidase exist as homodimers (29, 30), pristanoyl-CoA oxidase is thought to exist as a homooctamer (31). To our knowledge, our work is the first to provide evidence that acyl-CoA oxidases can function as heterodimers. The crystal structure of rat palmitoyl-CoA oxidase homodimer bound to a fatty acid suggests that substrate binding occurs at the dimer interface (32, 33). Thus, acyl-CoA oxidase heterodimers may form a composite binding site at their interface that is different from the corresponding homodimers and thus shows an altered substrate preference. In addition to ACOX-1, -2, and -3, there are several other acyl-CoA oxidases in C. elegans that may participate in ascaroside biosynthesis (Fig. S2). ACOX-1 is also predicted to have three different splice variants that could potentially play specific roles in ascaroside biosynthesis. Different splice variants of human palmitoyl-CoA oxidase have been reported to have different fatty acid chain length preferences (26).

Our work demonstrates that β-oxidation enzymes act directly on long-chain ascarosides to shorten them, as opposed to acting on long-chain fatty acids or hydroxylated fatty acids that once shortened are subsequently attached to the ascarylose sugar. Thus, we have established the order of the main steps in ascaroside biosynthesis, which will likely provide insight into pheromone biosynthesis not only in C. elegans but in other nematode species as well. Furthermore, our work provides a general framework for understanding the effects of environmental conditions on ascaroside side-chain length and pheromone composition. This knowledge will shed light on how nematodes respond to a changing environment and adapt accordingly.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans Liquid Cultures.

Strains are listed in SI Materials and Methods. Large-scale (150 mL) nonsynchronized worm cultures were fed E. coli (HB101) and grown for 9 d, and extracts were generated from the culture medium and analyzed by LC-MS/MS, as described (16). Small-scale (50 mL) synchronized worm cultures were used to test the effects of environmental conditions on ascaroside production and acyl-CoA oxidase gene expression, as described in SI Materials and Methods. For sample collection in these experiments, 5 mL culture was centrifuged (800 × g for 2 min), the worms at the bottom were removed, and the supernatant was centrifuged again (2,671 × g for 10 min). One milliliter of this supernatant was lyophilized and resuspended in 100 μL of 50% (vol/vol) methanol in water, and the ascarosides were analyzed by LC-MS as described (16) with modifications (SI Materials and Methods). The worms obtained were washed with cold M9 buffer several times, flash-frozen, and stored at −80 °C until they were used for qRT-PCR (SI Materials and Methods).

Acyl-CoA Oxidase Expression and Biochemical Assay.

acox-1a and acox-2 were each cloned by PCR from a C. elegans (N2) cDNA library, and a codon-optimized version of acox-3 was chemically synthesized (GenScript). acox-1a and acox-2 were inserted into a modified pET-16b vector at the NcoI/NotI restriction sites (C-terminal His tag). The plasmids were individually transformed into BL21(DE3) cells, and expression was induced overnight at 16 °C using 0.6 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). For coexpression experiments, acox-1a was inserted into pACYCDuet-1 at the NcoI/NotI sites (with either no tag or a C-terminal FLAG tag), acox-2 was inserted into a modified pET-16b vector at the NcoI/NotI sites (C-terminal His tag), and acox-3 was inserted into a modified pET-16b vector at the NcoI/NotI sites (C-terminal His tag). The plasmids were cotransformed into BL21(DE3) cells, and expression was induced overnight at 20 °C using 0.5 mM IPTG. Cells were lysed using a microfluidizer. The protein was purified with Ni-NTA resin (Thermo Fisher), concentrated with a 10 kDa-cutoff Centricon (Millipore), further purified on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) attached to an FPLC, and concentrated again to 1 mg/mL for assay. The acyl-CoA oxidase activity assay was based on a previously reported method (25) with modifications (SI Materials and Methods).

Synthesis of CoA-Thioesters.

Ascarosides were synthesized as previously described (34), and (R)-6-hydroxyheptanoic acid and (R)-8-hydroxynonanoic acid were synthesized as described in SI Materials and Methods. CoA-thioesters of ascarosides, fatty acids, and hydroxylated fatty acids (1–9) were synthesized based on a previously described method for making fatty acyl-CoA thioesters (35) with modifications (SI Materials and Methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kyle Hollister, Mark Spell, and Justin Ragains for providing initial stocks of several ascarosides that enabled us to obtain preliminary data. We thank Scott Neal and Sarah Hall for advice, and Shohei Mitani at the National BioResource Project (Japan) for strains. Some strains were also provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM87533) and the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1423951112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Golden JW, Riddle DL. A pheromone influences larval development in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1982;218(4572):578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.6896933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butcher RA, Fujita M, Schroeder FC, Clardy J. Small-molecule pheromones that control dauer development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(7):420–422. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butcher RA, Ragains JR, Kim E, Clardy J. A potent dauer pheromone component in Caenorhabditis elegans that acts synergistically with other components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14288–14292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806676105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher RA, Ragains JR, Clardy J. An indole-containing dauer pheromone component with unusual dauer inhibitory activity at higher concentrations. Org Lett. 2009;11(14):3100–3103. doi: 10.1021/ol901011c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pungaliya C, et al. A shortcut to identifying small molecule signals that regulate behavior and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(19):7708–7713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811918106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassada RC, Russell RL. The dauerlarva, a post-embryonic developmental variant of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1975;46(2):326–342. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan J, et al. A blend of small molecules regulates both mating and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2008;454(7208):1115–1118. doi: 10.1038/nature07168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izrayelit Y, et al. Targeted metabolomics reveals a male pheromone and sex-specific ascaroside biosynthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(8):1321–1325. doi: 10.1021/cb300169c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macosko EZ, et al. A hub-and-spoke circuit drives pheromone attraction and social behaviour in C. elegans. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1171–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature07886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasan J, et al. A modular library of small molecule signals regulates social behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(1):e1001237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Reuss SH, et al. Comparative metabolomics reveals biogenesis of ascarosides, a modular library of small-molecule signals in C. elegans. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(3):1817–1824. doi: 10.1021/ja210202y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Artyukhin AB, et al. Succinylated octopamine ascarosides and a new pathway of biogenic amine metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(26):18778–18783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.477000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim K, et al. Two chemoreceptors mediate developmental effects of dauer pheromone in C. elegans. Science. 2009;326(5955):994–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1176331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrath PT, et al. Parallel evolution of domesticated Caenorhabditis species targets pheromone receptor genes. Nature. 2011;477(7364):321–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fielenbach N, Antebi A. C. elegans dauer formation and the molecular basis of plasticity. Genes Dev. 2008;22(16):2149–2165. doi: 10.1101/gad.1701508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X, Noguez JH, Zhou Y, Butcher RA. Analysis of ascarosides from Caenorhabditis elegans using mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1068:71–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-619-1_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butcher RA, et al. Biosynthesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(6):1875–1879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810338106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joo HJ, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans utilizes dauer pheromone biosynthesis to dispose of toxic peroxisomal fatty acids for cellular homoeostasis. Biochem J. 2009;422(1):61–71. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joo HJ, et al. Contribution of the peroxisomal acox gene to the dynamic balance of daumone production in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(38):29319–29325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poirier Y, Antonenkov VD, Glumoff T, Hiltunen JK. Peroxisomal β-oxidation—A metabolic pathway with multiple functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(12):1413–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan F, et al. Ascaroside expression in Caenorhabditis elegans is strongly dependent on diet and developmental stage. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noguez JH, et al. A novel ascaroside controls the parasitic life cycle of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(6):961–966. doi: 10.1021/cb300056q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choe A, et al. Ascaroside signaling is widely conserved among nematodes. Curr Biol. 2012;22(9):772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson O, et al. The million mutation project: A new approach to genetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 2013;23(10):1749–1762. doi: 10.1101/gr.157651.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu R, et al. Overexpression and characterization of the human peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase in insect cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(9):4908–4915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oaxaca-Castillo D, et al. Biochemical characterization of two functional human liver acyl-CoA oxidase isoforms 1a and 1b encoded by a single gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360(2):314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Linden AM, et al. Genome-wide analysis of light- and temperature-entrained circadian transcripts in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(10):e1000503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garsin DA, et al. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300(5627):1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osumi T, Hashimoto T, Ui N. Purification and properties of acyl-CoA oxidase from rat liver. J Biochem. 1980;87(6):1735–1746. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Veldhoven PP, Van Rompuy P, Vanhooren JC, Mannaerts GP. Purification and further characterization of peroxisomal trihydroxycoprostanoyl-CoA oxidase from rat liver. Biochem J. 1994;304(Pt 1):195–200. doi: 10.1042/bj3040195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Veldhoven PP, Van Rompuy P, Fransen M, De Béthune B, Mannaerts GP. Large-scale purification and further characterization of rat pristanoyl-CoA oxidase. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222(3):795–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tokuoka K, et al. Three-dimensional structure of rat-liver acyl-CoA oxidase in complex with a fatty acid: Insights into substrate-recognition and reactivity toward molecular oxygen. J Biochem. 2006;139(4):789–795. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arent S, Pye VE, Henriksen A. Structure and function of plant acyl-CoA oxidases. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46(3):292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollister KA, et al. Ascaroside activity in Caenorhabditis elegans is highly dependent on chemical structure. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(18):5754–5769. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaguchi A, Yoshimura T, Okuda S. A new method for the preparation of acyl-CoA thioesters. J Biochem. 1981;89(2):337–339. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.