Abstract

T-regulatory (Treg) cells are important to immune homeostasis, and Treg cell deficiency or dysfunction leads to autoimmune disease. A histone/protein acetyltransferase (HAT), p300, was recently found to be important for Treg function and stability, but further insights into the mechanisms by which p300 or other HATs affect Treg biology are needed. Here we show that CBP, a p300 paralog, is also important in controlling Treg function and stability. Thus, while mice with Treg-specific deletion of CBP or p300 developed minimal autoimmune disease, the combined deletion of CBP and p300 led to fatal autoimmunity by 3 to 4 weeks of age. The effects of CBP and p300 deletion on Treg development are dose dependent and involve multiple mechanisms. CBP and p300 cooperate with several key Treg transcription factors that act on the Foxp3 promoter to promote Foxp3 production. CBP and p300 also act on the Foxp3 conserved noncoding sequence 2 (CNS2) region to maintain Treg stability in inflammatory environments by regulating pCREB function and GATA3 expression, respectively. Lastly, CBP and p300 regulate the epigenetic status and function of Foxp3. Our findings provide insights into how HATs orchestrate multiple aspects of Treg development and function and identify overlapping but also discrete activities for p300 and CBP in control of Treg cells.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic transcription is tightly regulated by histone modifications, including acetylation of lysine residues of histone tails (1). Acetylation is controlled by the competing actions of histone/protein acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone/protein deacetylases (HDACs), which also regulate the acetylation of many nonhistone proteins. Three main families of HATs are reported: CBP/p300, GNAT (GCN5/PCAF), and MYST (2). CBP and p300 have high sequence homology (1) but share little sequence similarity with other HAT enzymes (3). CBP (KAT3A) and p300 (KAT3B) function as transcriptional coactivators, acetyltransferases, and ubiquitin ligases and interact with multiple transcription factors (4). Changes resulting in homozygous CBP or p300 knockout mice or CBP/p300 doubly heterozygous mice are invariably lethal (5), consistent with the widespread roles of these molecules in cell growth and development. CBP- and p300-deficient embryos have phenotypes that are partially distinct from those of p300 and CBP heterozygous null mice (5, 6), suggesting they are not interchangeable and have different substrate specificities. For example, CBP and p300 exhibit distinct specificities on acetylating histones (7, 8), and they can acetylate the same lysines with different degrees of efficiency (9). Biologically, CBP promotes but p300 inhibits transcription of the antiapoptotic survivin gene (10). Likewise, loss of CBP, but not loss of p300, increases the proportion of CD8 singly positive thymocytes and the likelihood of development of T cell lymphoma (11, 12). Lastly, retinoic acid-induced transcriptional upregulation of the p21Cip1 cell cycle inhibitor required p300 but did not require CBP, whereas the reverse was true for p27Kip1 induction by F9 cells (13).

T-regulatory (Treg) cells (Tregs) are essential for immune homeostasis, preventing autoimmunity, and limiting chronic inflammation. Foxp3 is the key transcription factor required for Treg cell development and function. Foxp3 deficiency or loss-of-function mutations result in severe autoimmunity in mice and humans (14, 15). Foxp3 induction, stability, and function are subject to epigenetic regulation. For example, an E3 ligase, PIAS1, regulates Foxp3 production by recruiting DNA methyltransferases and heterochromatin protein-1 to the Foxp3 promoter and thereby maintains a repressive chromatin structure (16). The demethylation status of the CpG-rich Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) of the Foxp3 conserved noncoding sequence 2 (CNS2) region correlates with Treg cell stability (17). In addition, fusion of green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the Foxp3 N terminus, to create Foxp3gfp reporter mice, was found to decrease Treg function due to interference with the normal association of Foxp3 with Tip60, p300, and HDAC7 (18). Our previous studies showed that p300 is important for Treg stability and function and that p300 targeting promotes antitumor immunity (19). Here, we explored the roles of CBP alone, and in conjunction with p300, in Treg production and suppressive function, using CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre and CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Like p300, CBP proved important for Treg stability and function in inflammatory settings. Unexpectedly, combined deletion of CBP and p300 in Treg cells (Tregs) led to lethal autoimmunity in very early life, accompanied by decreased expression of characteristic Treg genes, dysregulated inflammatory gene expression, rampant host T cell responses, and widespread mononuclear cell infiltration of host tissues. Our findings indicate an indispensable role for CBP and p300 in controlling the development and functions of the Foxp3+ Treg cell lineage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal experiments.

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (no. 2011-7-746 and 2016-6-561). We purchased CD90.2+, CD90.1+, and Rag1−/− C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory), and p300fl/fl and CBPfl/fl mice were described previously (11). Foxp3YFP-cre mice (20) were provided by Alexander Rudensky (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions and used for experiments at 3 to 8 weeks of age.

Abs, flow cytometry, and cell sorting.

We purchased conjugated monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) for flow cytometry (BD Pharmingen or eBioscience), including Pacific blue-CD4, allophycocyanin (APC)-Foxp3, phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7-CD62L, APC-CD44, APC-CD25, APC-GITR, PE-CTLA4, APC-GATA3, PE-Cy5.5-Ki67, APC-If, PE–IL-2, PE–interleulin-4 (IL-4), and APC–IL-17; we also used MAbs to mouse Foxp3 (FJK-16S; eBioscience), rabbit antibodies to β-actin (Cell Signaling), anti-acetyl-H3K9 (Upstate), and anti-CBP and anti-p300 antibodies (Santa Cruz). Acetyl-Foxp3-lysine31 antibody was produced at Covance (Princeton, NJ). We used a CyAn ADP color flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter), and data were analyzed by FlowJo 8 software (TreeStar). CD4+ yellow fluorescent protein-positive (YFP+) Tregs were sorted, based on YFP expression, with a FACSAria fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; BD Biosciences) at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) Flow Cytometry Core Facility.

Plasmids.

p300 expression vector was provided by Xiao-Jiao Yang (McGill University, Montreal, Canada). Mouse Foxp3 promoter luciferase vector and p65 expression vectors were provided by Youhai Chen (UPenn, Philadelphia, PA). CBP, GATA3, NFAT, and Runx1 expression vectors were purchased from Addgene. Foxp3-MinR1 was described previously (21).

Treg suppression assay.

CD4+ YFP− T-effector (Teff) cells (Teffs) and CD4+ YFP+ Treg cells were sorted from Foxp3YFP-cre, CBPfl/fl/Foxp3cre, or CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre mice by flow cytometry based on YFP expression. A total of 5 × 105 (CBPfl/fl/Foxp3cre) or 2.5 × 105 (CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre) Pacific blue-labeled Teff cells were stimulated with CD3 MAb (5 or 2.5 μg/ml) in the presence of 5 × 105 or 2.5 × 105 irradiated, syngeneic, T cell-depleted splenocytes (catalog no. 130-049-101; Miltenyi Biotec) and various ratios of Tregs. Proliferation of the effector T cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis of Pacific blue dilution 72 h later.

Luciferase assays.

293T cells were maintained (37°C, 5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, and streptomycin. Cells at 80% to 90% confluence were transfected with Foxp3 promoter luciferase reporter plus NFAT, Runx1, p65, p300, CBP, cyclic-AMP (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB), or empty vector, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 48 h later, cells were treated with 6 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma) for 5 to 6 h, and luciferase activities of whole-cell lysates were analyzed with a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega).

Confocal microscopy.

Tregs were sorted from lymph nodes (LNs) and spleens of Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre mice. Sorted Tregs were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-Foxp3 (rat), anti-CBP (rabbit), anti-p300 (rabbit), or anti-AcH3K9 (rabbit) antibody, plus fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or PE-conjugated secondary antibody. Images were taken with a Zeiss Wildfield microscope at the UPenn Confocal Core Facility.

Western blotting.

Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and immunoblotted using the indicated Abs. Image-J software (NIH) was used to quantify blot intensity.

Oligonucleotide pulldown assays.

For cyclic-AMP response element binding protein/activating transcription factor (CREB/ATF) oligonucleotide pulldown assays, 293T cells were transfected with empty vector, CREB, or CREB plus CBP expression vectors for 40 h and then stimulated for 5 h with PMA and ionomycin plus forskolin for 15 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions (catalog no. AY2002; Panomics). For Foxp3 oligonucleotide pulldown assays, lysates (100 μg) of 293T cells, transfected with empty vector or Foxp3 with or without CBP and p300 expression vectors for 48 h, were diluted in buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1% NP-40). Nuclear extracts or cell lysates were incubated (overnight, 4°C) with 10 μg poly(IC) (Roche), 50 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads (Sigma), and biotinylated oligonucleotides containing wild-type (WT) or mutant CREB/ATF binding sites (see Fig. 2i) or putative Foxp3 binding sites (22) with the sequence 5′-CAA GGT AAA CAA GAG TAA ACA AAG TC-3′. Beads were washed 5 times in dilution buffer, resuspended in 60 μl SDS sample loading buffer (Bio-Rad), heated at 95°C for 10 min, separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed using rabbit anti-pCREB or rat anti-mouse Foxp3 MAb.

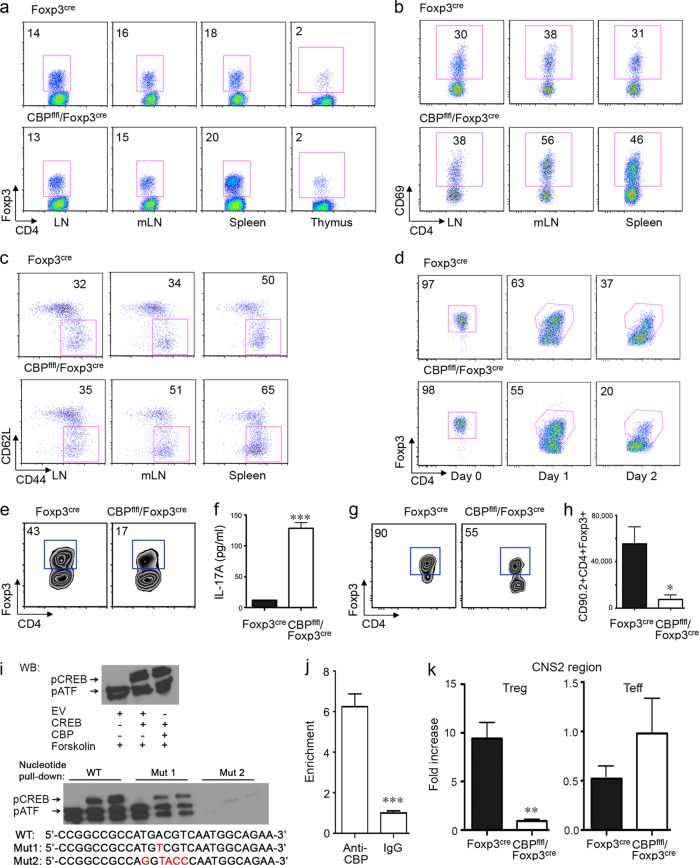

FIG 2.

Conditional deletion of CBP in Tregs decreases pCREB binding to the CNS2 region and impairs Treg stability. (a) Percentages of CD4+ YFP+ (Foxp3+) cells in LNs, mesenteric LNs (mLN), spleens, and thymi of Foxp3YFP-cre and CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. (b and c) Percentages of CD4+ YFP+ (Foxp3+) CD69+ (b) and CD4+ YFP+ (Foxp3+) CD44hi CD62Llow (c) cells in Foxp3YFP-cre and CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice; cells were gated on CD4+ YFP+ cells. (d and e) CD4+ YFP+ cells (1 × 105) were sorted from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and stimulated in vitro with plate-bound CD3/CD28 MAbs for 48 h (d) or for 7 days with the addition of IL-2 (50 U/ml) and IL-6 (50 U/ml) (e), and the percentages of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells were determined. (f) ELISA determinations (means ± standard deviations [SD]) of IL-17A levels in supernatants of the cells described for panel e. Data are representative of the results of 3 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (g and h) Percentages (g) and absolute numbers (h) of CD90.2+ CD4+ Foxp3+ cells at 4 weeks after i.v. adoptive transfer of 1 × 105 CD4+ YFP+ cells, isolated by cell sorting from CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre or Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs, into Rag1−/− host mice; each sorted Treg population was cotransferred with 5 × 105 CD4+ CD25− CD90.1+ T cells. *, P < 0.05. (i) To assess DNA binding at the CREB/ATF binding site of the Foxp3 CNS2 region, 293T cells were transfected with empty vector (EV), CREB, or CREB plus CBP for 40 h and stimulated for 5 h with PMA and ionomycin plus forskolin (10 μM) for 15 min. Nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blot and oligonucleotide pulldown assays. The WT and mutant CREB/ATF binding sequences used in the pulldown assays are shown in the figure. For each set of 3 lanes, lane 1 represents EV alone, lane 2 represents CREB plus EV, and lane 3 represents CREB plus CBP. (j) CBP binding to the CNS2 region as determined by ChIP-qPCR assays. CD4+ CD25+ Tregs were isolated from B6 mice, stimulated with PMA-ionomycin for 2 h, and analyzed by ChIP assays, with pulldown by anti-CBP or IgG antibody. (k) pCREB binding to the CNS2 region as determined by ChIP-qPCR assays. CD4+ CD25+ Tregs and CD4+ CD25− Teffs were isolated from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice, stimulated with PMA-ionomycin for 2 h and forskolin (10 μM) for 15 min, and subjected to ChIP assay, with pulldown by anti-pCREB or IgG antibody. Data show the ratios of anti-pCREB to IgG values, and the IgG pulldown value was set to 1-fold (**, P < 0.01). Data are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR).

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized with TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (catalog no. N808-0234; Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Universal PCR master mix, and specific primers were bought from Applied Biosystems.

ChIP assays.

These were performed with an EZ-Magna CHIP A/G chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) kit (catalog no. 17-408; Upstate). Briefly, DNA-chromatin complexes were isolated from 1 to 2 million Treg or Teff cells, and genomic DNA was precipitated using 10 μg of Abs against p300, CBP (Santa Cruz), Foxp3 (Santa Cruz), pCREB (catalog no. 17-1013; Upstate), or control IgG. Genomic DNA in each precipitate was probed by qPCR for the Foxp3 promoter using forward primer 5′ TTC CCA TTC ACA TGG CAG GCT TCA 3′ and reverse primer 5′ TGA GAT AAC AGG GCT CAT GAG AAA CCA CA 3′ and for the GATA3 promoter using forward primer 5′ GTC ACA ATA CCA ACC TGA GTA GCA A 3′ and reverse primer 5′ GAG ACA TAG AGA GCT ACG CAA TCT GA 3′.

DNA methylation.

The CpG DNA methylation at the Foxp3 TSDR (Treg-specific demethylated region), also known as CNS2, was determined by sodium bisulfite conversion, following by PCR amplification and sequencing of individual clones. Briefly, 200 to 500 ng of DNA from Teff or Treg cells was subjected to bisulfite conversion according to the instructions of the manufacturer (methyl detector; Active Motif) and used for two rounds of PCR performed with primers as described previously (23). PCR products (502 bp) were separated on agarose gels, purified, cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and transformed into bacterial clones. Plasmid DNA from each clone was sequenced by the CHOP sequencing facility.

Treg stability in vivo.

We adoptively transferred, intravenously (i.v.), 0.1 million FACS-sorted high-purity Tregs (CD90.2+ CD4+ YFP+) alone, or along with 0.5 million Teff cells (CD90.1+ CD4+ CD25−), to CD90.1+ mice or Rag1−/− mice. Spleens were harvested 4 weeks later for flow cytometric analysis.

Colitis.

A total of 0.5 million CD90.1+ CD4+ CD25− Teff cells were adoptively transferred, i.v., to B6/Rag1−/− mice, and their weights were monitored daily. Clinically significant colitis developed around day 10 postinjection, with 5% to 15% weight loss. At that point, 3 × 105 FACS-sorted CD4+ YFP+ (Foxp3+) Tregs from Foxp3cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3cre mice were adoptively transferred to colitic mice. At the end of the study, gut and lymphoid tissues were collected for histology.

Microarrays.

RNA was extracted with RNeasy kits (Qiagen), and RNA integrity and quantity were analyzed by photometry (DU640; Beckman-Coulter). Microarray experiments were performed with whole-mouse-genome oligoarrays (Mouse430a 2.0; Affymetrix), and array data were analyzed with MAYDAY 2.13 (24). Array data were subjected to robust multiarray average normalization. Normalized data were used for calculating fold changes of gene expression that had increased or decreased by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and data with >1.5-fold differential expression (P, <0.05; Storey false-discovery rate, <0.1) were included in the analysis. Data underwent z-score transformation for display. Data shown as fold changes in RNA expression relative to expression of a shared WT control measured during the same experiment. Gene expression correlation between CBPfl/fl Foxp3cre and p300fl/fl Foxp3cre Tregs was analyzed by Spearman correlation.

ELISA.

FACS-sorted CD4+ YFP+ Tregs from Foxp3cre or CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre mice were stimulated with plate-bound CD3 and CD28 MAbs, IL-2 (Roche) (50 U/ml), and IL-6 (eBioscience) (50 U/ml) for 7 days. IL-17A within culture supernatants was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (88-7371-22; eBioscience).

Generation of bone marrow chimeras.

Bone marrow cells were isolated from Foxp3YFP-cre and CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3cre mice (CD90.2+ background) and depleted of T cells with anti-CD90.2 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Bone marrow cells from Foxp3YFP-cre and CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3cre mice were mixed with bone marrow cells from Thy1.1 mice at a ratio of 1:1. Mixed bone marrow cells (8 million per recipient) were transferred to RAG1−/− mice, and 11 weeks later, thymus, LNs, and spleen were harvested from each recipient and Foxp3 expression was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Autoantibody screen.

Sera from CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre mice (n = 5) or WT mice (n = 3) were diluted 1/5 (1/2 starting dilution for islet cell antibodies [ICAs]) and incubated with cryosections from normal male and female C57BL/6 mice for 45 min. Sections were then washed in PBS and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) (1:200, 30 min). In addition to use of pooled WT healthy sera, negative controls included incubation with secondary antibody alone. Pooled sera from NZB mice with known autoantibodies served as positive controls.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0d, and data are displayed as means ± standard deviations. Measurements for comparisons between two groups were performed with Student's t test.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

We deposited our data in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE60318.

RESULTS

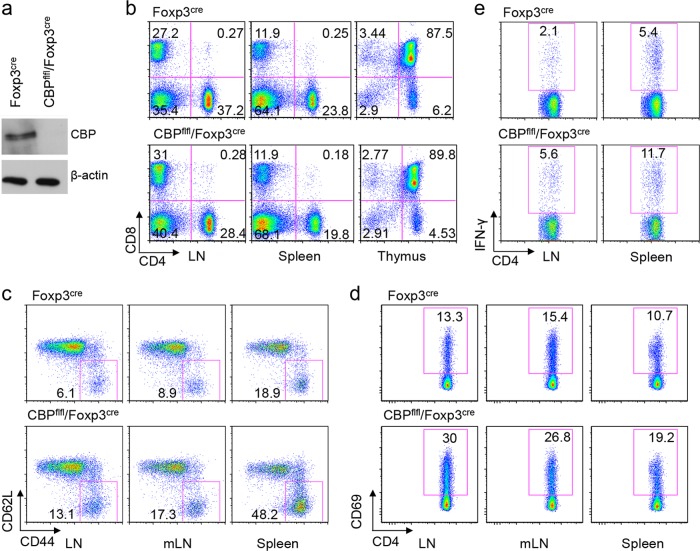

CBP gene deletion in Treg cells causes Teff cell activation.

CBP and p300 have 63% sequence identity and are functionally conserved, and we recently showed that p300 is required for Tregs to limit host immunity under inflammatory conditions (19). To now assess the role of CBP, we conditionally deleted CBP in Tregs by mating CBPfl/fl mice with Foxp3YFP–cre mice (20) (Fig. 1a). CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice were born at expected Mendelian ratios and initially developed normally, but by 8 to 10 weeks of age, 50% of these mice had enlarged peripheral lymphoid tissues (data not shown). While CBP deletion in the Treg population did not affect CD4 or CD8 T cell development (Fig. 1b), compared to littermate controls, CD4+ Foxp3− T-effector (Teff) cells in lymph nodes and spleens of CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice had increased expression of markers of immune activation, including CD44hi CD62Llow (Fig. 1c), CD69 (Fig. 1d), and GITR and CTLA4 (data not shown). In addition, CD4+ Foxp3− Teff cells from CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice had increased gamma interferon (IFN-γ) expression (Fig. 1e). These data indicate that CBP expression within Foxp3+ Tregs is important for control of systemic Teff cell activation.

FIG 1.

Conditional deletion of CBP in Tregs leads to activation of conventional host T cells. Data are from 2- to-4-month-old mice (n = 4 mice/group). (a) Western blot assay showing CBP deletion in Tregs. Tregs were sorted from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice based on CD4+ YFP+ staining, and β-actin was used as a loading control. (b) Percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes (LN), spleens, and thymi of Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. (c and d) Percentages of CD44hi CD62Llow (c) and CD4+ CD69+ (d) cells in LNs, mesenteric LNs (mLN), and spleens of Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. (e) Percentages of CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells in LNs and spleens of Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Data are representative of the results of at least 3 independent experiments.

CBP is important for Treg stability in promoting pCREB binding to the CNS2 region of Foxp3.

We next assessed whether CBP contributes to Foxp3 expression within Tregs. Compared with the results seen with littermate control mice, CBP deletion in Tregs did not affect the levels of Foxp3 mRNA (data not shown) or Foxp3 protein (Fig. 2a) under normal, resting conditions. Likewise, the proportions of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues of CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFPcre mice were comparable to those of littermates at up to 7 months of age (data not shown). These findings are similar to those seen in p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice (19). Compared to littermate cells, splenic CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs had less CD25 expression, but expression of CTLA4 and GITR was normal (data not shown). However, CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs showed modest increases in expression of several activation markers, including CD69 and CD44hi CD62Llow, especially within mesenteric lymph nodes and spleen (Fig. 2b and c), indicating a degree of Treg cell activation even under basal conditions. We also investigated whether CBP affected Treg stability. Compared to wild-type (WT) CD4+ YFP+ Tregs, CD3/CD28 MAb activation of FACS-sorted, high-purity CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs resulted in decreased proportions of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells at 48 h of stimulation (Fig. 2d). Likewise, compared to WT Tregs, culture of CBP-deleted Tregs for 7 days in the presence of CD3/CD28 MAbs, plus IL-2 and IL-6, resulted in fewer CD4+ Foxp3+ cells (Fig. 2e) and increased IL-17A level production (Fig. 2f). These data suggested that CBP is required for Tregs to sustain a high level of Foxp3 expression under activating or inflammatory conditions, at least in vitro.

To test whether CBP was required for maintenance of Foxp3 expression in vivo, Tregs isolated by cell sorting from Foxp3YFP–cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice (CD90.2+ background) were adoptively transferred, i.v., along with CD90.1+ Teff cells, into Rag1−/− mice. Analysis at 4 weeks posttransfer showed that, compared to WT controls, immunodeficient mice receiving CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre Tregs had decreased proportions (Fig. 2g) and absolute numbers (Fig. 2h) of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells, though Treg cell proliferation levels were comparable in the 2 sets of mice (data not shown). In contrast to these findings in immunodeficient mice, Foxp3+ Treg proportions and absolute numbers were comparable in immunocompetent mice adoptively transferred with WT or CBP-deleted CD4+ YFP+ Tregs (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that, similarly to the effects of p300 deletion in Tregs, CBP is important for Foxp3+ Treg stability under inflammatory or lymphopenic conditions.

Cyclic AMP response element binding protein/activating transcription factor (CREB/ATF) binding to the CNS2 region of the Foxp3 gene is critical for T cell receptor (TCR)-induced Foxp3 expression (25), and phosphorylation of CREB leads to CBP recruitment and enhances pCREB activities (26, 27). To assess whether CBP promotes CNS2 binding by pCREB, we performed oligonucleotide pulldown analyses using oligonucleotides representing WT or mutant CREB/ATF binding sites. In the presence of forskolin, an activator of cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase (PKA) in vitro, CBP did not increase pCREB expression. However, CBP enhanced pCREB binding to oligonucleotides representing WT but not mutant CREB/ATF binding sites (Fig. 2i); CBP no longer enhanced pCREB binding to the oligonucleotides of mutant 1, and pCREB could not bind to the oligonucleotides of mutant 2.

To test if CBP affects pCREB binding to Foxp3 CNS2 in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays of CBP precipitates from nuclear lysates isolated from C57BL/6 Tregs and found CBP accumulation at the Foxp3 CNS2 region (Fig. 2j). ChIP assays of pCREB binding to the CSN2 region in WT versus CBP-deleted Tregs showed that CBP deletion markedly decreased pCREB accumulation following stimulation with TCR plus forskolin. However, in a control experiment, we did not find any obvious effects on pCREB binding to the CNS2 region in WT versus CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre Teff cells (Fig. 2k). As demethylation of the CpG islands in the Foxp3 CNS2 region is correlated with CREB binding (25), we assessed methylation of this region in Teffs and Tregs from WT versus CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice. Consistent with previous studies (17), Teff cells had 100% CNS2 methylation, and Tregs from both sets of mice exhibited almost 100% CNS2 demethylation (data not shown), suggesting that CBP promotes Foxp3 expression under conditions of TCR stimulation by enhancing pCREB DNA binding ability without affecting CpG island methylation.

CBP is important for Treg function during inflammation.

CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre Tregs had mildly impaired suppressive function in vitro (Fig. 3a). To put this into perspective, we used 2 experimental models to examine whether CBP is necessary for Treg suppressive function in vivo. First, in an adoptive cell transfer model of colitis, once Rag1−/− mice injected i.v. with CD4+ Foxp3− Teff cells had developed wasting and 5% to 15% weight loss, they were adoptively injected i.v. with highly purified CD4+ YFP+ (Foxp3+) Tregs sorted from Foxp3YFP–cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice. While Foxp3YFP–cre Tregs reversed development of the colitis, transfer of CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre Tregs did not rescue the mice from ongoing colitis (Fig. 3b and c). In a second in vivo model, BALB/c cardiac allografts were transplanted into Foxp3YFP–cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP–cre mice, and recipients were treated with a transfusion of CD154 MAb plus donor splenocyte (19). While control mice maintained their allografts over the long term (>100 days), mice with CBP-deleted Tregs acutely rejected their allografts (Fig. 3d). Comparison of allografts from the 2 groups showed that CBP deletion was associated with decreased intragraft Foxp3 expression and increased CD8 and IFN-γ mRNA levels (Fig. 3e). Hence, CBP is important for normal Treg survival and suppressive function in clinically relevant models of disease.

FIG 3.

CBP is important for Treg function in vivo and in vitro. (a) CD4+ YFP+ cells were sorted from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and incubated with Pacific blue Cell-Tracker-labeled Foxp3YFP-cre CD4+ YFP− Teff cells, irradiated APC, and CD3 MAb for 3 days; percentages of proliferating Teff cells are shown. Data are representative of the results of 3 independent experiments. (b) B6/Rag1−/− mice injected with 5 × 105 B6 CD4+ CD25− Teff cells developed colitis and weight loss after 5 days. Mice developing 5% to 15% weight loss were adoptively transferred i.v. with 3 × 105 CD4+ YFP+ (Foxp3+) Tregs sorted from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Data are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments performed with 5 mice/group. (c) Representative hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained sections of colons collected at 3 weeks post-Teff cell transfer (×100 magnifications). (d) Comparison of rates of BALB/c cardiac allograft survival in Foxp3YFP-cre and CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice (5 mice/group) that received CD154 MAb and a donor splenocyte transfusion (DST) at the time of engraftment (**, P < 0.01). (e) qPCR analysis of Foxp3, CD8, and IFN-γ mRNA expression in allografts harvested at 3 weeks posttransplantation from CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice versus Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Data are representative of the results of 3 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

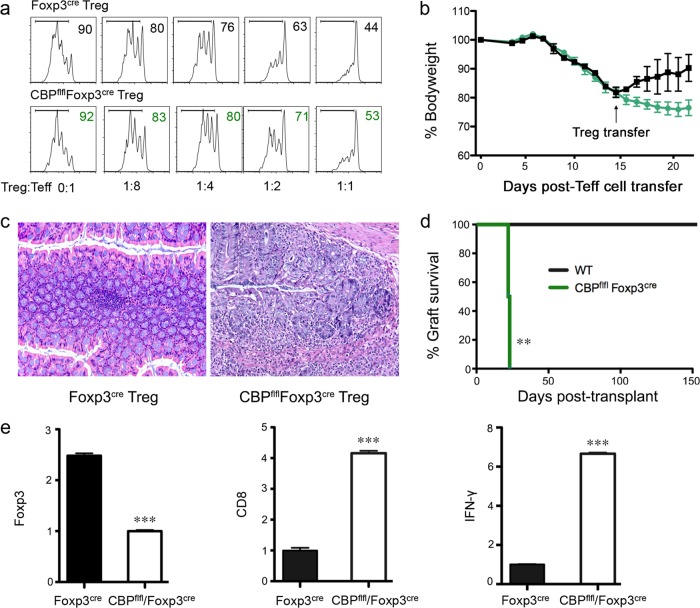

Treg-specific deletion of CBP and p300 leads to rapid and lethal autoimmunity.

Given their close structural homology, CBP and p300 may have redundant functions in control of CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg production. Consistent with this, we did not observe effects of CBP or p300 deletion on murine Treg production. However, mice generated with Treg-specific deletion of both genes (CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre) developed severe autoimmunity and died within 3 to 4 weeks of birth. Compared to Foxp3YFP-cre littermate controls, these mice were runted, had shrunken thymi, enlarged lymph nodes, and comparably sized spleens, and developed circumferential rings on their tails (Fig. 4a and b). By the time the mice had reached 3 weeks of age, histology showed mononuclear cell infiltration of multiple organs (Fig. 4c; see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and autoantibody screening showed a range of autoantibody production involving multiple organs (see Table S2). This severe phenotype is very similar to that of scurfy (14) or other Foxp3 mutant mice and shows that Treg expression of both CBP and p300 is critical in protecting mice from developing life-threatening autoimmune diseases.

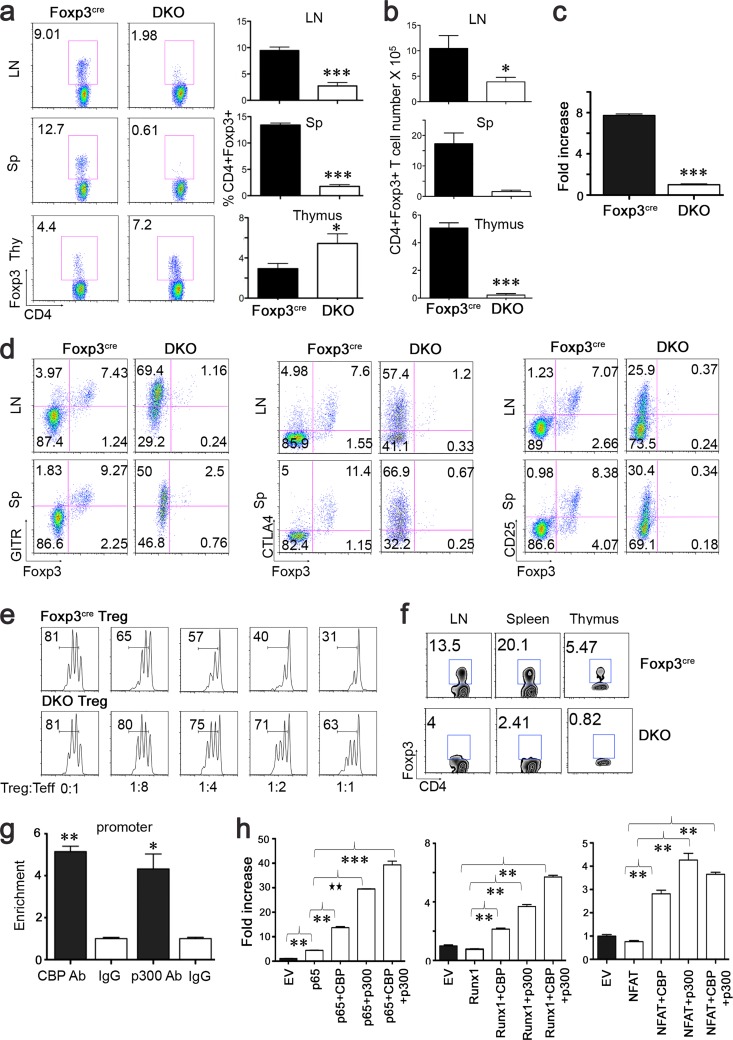

FIG 4.

Conditional deletion of CBP and p300 in Foxp3+ Tregs (CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice) leads to lethal autoimmunity. Data are from 3-week-old male mice. Compared to controls, CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice were sick, were runted, and showed circumferential rings on their tails (a) and had enlarged LNs, comparably sized spleens, and shrunken thymi (b). (c) Representative histologic sections (n = 5 to 7 mice) of bone marrow, thymus, lymph node, spleen, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, eye, and skin from CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice (×100 magnifications). (d) Percentages of CD4 and CD8 T cells in LNs, spleens, and thymi of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and littermates (Foxp3YFP-cre). (e) Pooled data (means ± SD) from the mice whose results are shown in panel d. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (f) Left and center columns show percentages of CD4+ CD44hi CD62Llow, CD4+ CD69+, CD4+ CD25+, CD4+ CTLA4+, CD4+ GITR+, and CD4+ Ki67+ cells in the lymph nodes and spleens of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and littermates. The right-hand column shows intracellular expression of cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17) by CD4 and CD8 Teff cells, as indicated, following isolation of single cells from LNs and spleens and stimulation with PMA-ionomycin for 5 to 6 h. Data are representative of the results of 3 experiments.

During backcrossing to obtain dual deletion of p300 and CBP in Foxp3+ Tregs, we found that mice with differing extents of CBP and p300 deletion in Tregs had distinct phenotypes. While CBPfl/wt p300fl/wt Foxp3YFP-cre mice showed long-term survival without overt disease, CBPfl/fl p300fl/wt Foxp3YFP-cre mice began to develop autoimmune diseases around 3 months of age, and CBPfl/wt p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice began to manifest autoimmune diseases, including lymphadenopathy, wasting, and dermatitis, by 8 weeks and died around 10 weeks of life (data not shown). These observations indicated that 2 (either CBP or p300) alleles together are required to prevent mice from developing severe autoimmune diseases. In addition, p300 may be more important than CBP with regard to controlling Treg development, since deletion of 3 alleles, including two p300 copies and one CBP copy, resulted in more-severe disease at earlier ages than deletion of two CBP and one p300 copies in Tregs.

To assess the mechanisms underlying the lethal immunopathology of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl dual-knockout (DKO) Foxp3YFP-cre mice, we first examined their CD4 and CD8 T cell populations. Compared to those of their littermates, levels of CD8+ CD4− cells were markedly increased in lymph nodes and spleens of DKO mice, and levels of CD4+ CD8− cells were also increased in spleens but not in lymph nodes (Fig. 4d and e). The thymi of DKO mice had decreased doubly positive but increased singly positive populations (Fig. 4d and e), likely reflecting severe thymic inflammation (28, 29). Deletion of up to 3 alleles of CBP plus p300 in Tregs did not significantly affect CD4 or CD8 production in lymph nodes or spleens, but CBPfl/wt p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice had small thymi and decreased doubly positive cell populations (data not shown), consistent with their relatively more severe phenotype.

Compared to WT littermates, CD4+ Foxp3− Teff cells from CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice had higher expression of activation and proliferation markers, including CD44hi CD62Llow, CD69, CD25, CTLA4, GITR, and Ki67 expression (Fig. 4f). CD4+ Foxp3− Teff cells of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice had increased expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 but not of IL-2 or IL-17, suggestive of increased differentiation with respect to Th1 and Th2 Teff cells, whereas their CD8+ Teff cells had higher levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 4f). Hence, CBP and p300 are critical for Foxp3+ Treg control of conventional Teff cell activation and cytokine production. We further investigated the effects on Teff activation of various deletions of CBP and p300 in Treg cells. While Teff cells from CBPfl/wt p300fl/wt Foxp3YFP-cre mice appeared normal, Teff cells from CBPfl/fl p300fl/wt Foxp3YFP-cre mice and, especially, CBPfl/wt p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice exhibited enhanced T cell activation (data not shown). These observations correlated with phenotypic features of the mice and suggest that p300 is more important for Treg development and function than CBP, though both genes contribute.

CBP and p300 cooperatively control Foxp3+ Treg production.

Compared to Foxp3YFP-cre controls, the thymi of mice whose Tregs lacked CBP and p300 mice had increased proportions of Foxp3 cells, though their absolute numbers of Tregs were decreased (Fig. 5a and b). In contrast, peripheral lymphoid tissues of DKO mice exhibited markedly decreased Treg counts, in terms of both proportions and absolute numbers (Fig. 5a and b), as well as significantly decreased levels of Foxp3 mRNA (Fig. 5c). As sole deletion of CBP or p300 had no significant effect on Treg production, the effects of dual deletion underscore the redundant roles of these paralogs in Treg cells. CBP and p300 deletion led to markedly decreased expression of classic Treg-associated markers, including GITR, CTLA4, and CD25 (Fig. 5d), and markedly impaired Treg suppressive function in vitro (Fig. 5e). Deletion of up to 3 alleles of CBP and p300, in various combinations, did not significantly affect Foxp3 populations in spleen and LN (data not shown), indicating that the retention of one copy of either CBP or p300 is sufficient for Foxp3 production. Likewise, deletion of any 3 alleles of CBP and p300 in Tregs did not significantly alter expression of Treg signature markers (data not shown). Therefore, one copy of either CBP or p300 is sufficient for Treg development and expression of functional markers.

FIG 5.

CBP and p300 are indispensable for Foxp3+ Treg production. Data are from 3-week-old male CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre and Foxp3YFP-cre mice. (a and b) Percentages (with means ± SD at right) (a) and absolute numbers (means ± SD) (b) of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells in LN, spleen, and thymus of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre and Foxp3YFP-cre mice; n = 7 mice/group for LNs and spleens and 3 mice/group for thymi. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001. (c) Foxp3 mRNA levels (means ± SD) of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre and Foxp3YFP-cre mice and qPCR analysis of Foxp3 mRNA in sorted Tregs from pooled LN and spleens of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice (n = 5) or littermates (n = 3). Data were normalized to 18S and are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (d) Percentages of Foxp3+ GITR+, Foxp3+ CTLA4+, and Foxp3+ CD25+ cells in CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and littermates. Cells were gated on CD4 cells. Data are representative of the results of 3 independent experiments. (e) In vitro Treg suppressive assay using FACS-isolated CD4+ YFP+ Tregs from pooled LN and spleen cells of Foxp3YFP-cre (n = 3) or CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice (n = 8) and Pacific blue cell Tracker-labeled Foxp3YFP-creCD4+ YFP− Teff cells, irradiated APC, and CD3 MAb with incubation for 72 h. Teff cell proliferation was determined by flow cytometry. Data are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments. (f) Mixed bone marrow chimeric mice were generated by injecting T cell-depleted bone marrow cells from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre (CD90.2 background) mice with C57BL/6 (CD90.1 background) cells at a 1:1 ratio into Rag1−/− recipient mice; 11 weeks later, percentages of CD90.2+ CD4+ Foxp3+ cells were determined by flow cytometry. Cells were gated on CD90.2+. Data are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments (n = 3 to 4 mice/group). (g) ChIP-qPCR assay showing CBP and p300 binding to the Foxp3 promoter region. CD4+ CD25+ Tregs from B6 mice were immunoprecipitated with anti-CBP or anti-p300 Abs, followed by qPCR analysis to detect CBP or p300 binding to the Foxp3 promoter region. Control IgG antibody binding was set as 1. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Data are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments. (h) Luciferase assays showing that CBP and p300 increased p65, Runx1, and NFAT transcription abilities in 293T cells that were transiently transfected with murine Foxp3-promoter-Luc vector plus expression vectors for p65, Runx1, NFAT, CBP, or p300 or empty vector (EV). EV was added to ensure that vials had equal DNA amounts. After 48 h, cells were treated with PMA-ionomycin for 5 to 6 h, and cell lysates were harvested for luciferase assays. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are representative of the results of 3 or more independent experiments.

To assess whether the effects of CBP and p300 on Foxp3 production are cell intrinsic, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Bone marrow cells from Foxp3YFP-cre or CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice (CD90.2+) were mixed with those of C57BL/6 (CD90.1+) mice and adoptively transferred to immunodeficient RAG1−/− mice. Transfer of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre bone marrow cells resulted in significantly fewer thymic, LN, and spleen CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells than did transfer of Foxp3YFP-cre bone marrow cells (Fig. 5f), confirming that CBP and p300 regulate Treg cell development in a cell-autonomous manner.

To investigate the mechanisms by which CBP and p300 regulate Foxp3 production, we undertook ChIP assays with anti-CBP and anti-p300 antibodies, using nuclear lysates isolated from Treg cells of normal B6 mice. Both CBP and p300 bound to the Foxp3 promoter (Fig. 5g). The NFAT, p65, and Runx1 transcription factors are reported to control Foxp3 gene expression by binding to the Foxp3 promoter (30, 31). We therefore used luciferase assays to determine whether CBP and/or p300 could affect transactivation by these transcription factors at the Foxp3 promoter (Fig. 5h). We found that CBP and p300 significantly improved the transactivating activity of p65, NFAT, and Runx1. In the cases of p65 and Runx1, the effects of the presence of CBP and p300 were additive, whereas for Runx1 and NFAT, the presence of either CBP or p300 was necessary to enable any transactivation activity at the Foxp3 promoter. These data indicate that recruitment of CBP and p300, and likely their acetyltransferase activities, is essential for the DNA binding/transcriptional ability of these key transcription factors at the Foxp3 promoter.

CBP and p300 cooperatively regulate Foxp3+ Treg function.

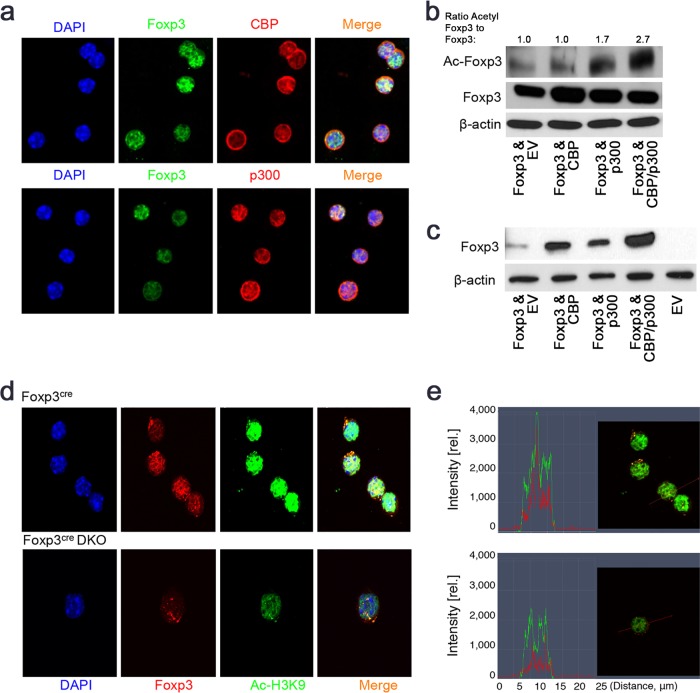

We, and others, have shown that p300 binds and acetylates Foxp3 (19, 21, 32). CBP and Foxp3 were colocalized within Treg nuclei (Fig. 6a), and overexpression of either CBP or p300 increased Foxp3 expression (Fig. 6b), consistent with an impaired Foxp3 protein level in CBP- or p300-deficient Tregs (Fig. 2e to h) and with our recent data (19). However, CBP and p300 together did not further increase the Foxp3 protein level, suggesting that CBP and p300 regulate the Foxp3 protein level via similar mechanisms. Increased Foxp3 expression was associated with increased Foxp3 acetylation, as shown using an antibody specific to the acetylated K31 of Foxp3 (33) (Fig. 6b). Levels of Foxp3 acetylation level were increased in the presence of both CBP and p300, indicating their complementary effects on Foxp3 acetylation. Additionally, the presence of either CBP or p300 increased Foxp3 DNA binding, and in the presence of CBP and p300 together, Foxp3 DNA binding was further increased (Fig. 6c). In the presence of CBP and p300, the Foxp3 DNA binding ability and acetylation level were further increased without an additional increase in Foxp3 expression, strongly suggesting that Foxp3 acetylation is correlated with its DNA binding. Specific histone modification markers (Ac-H3, Ac-H9, and H3K27me3) at Foxp3 binding sites are correlated with Foxp3-mediated transcription activation or repression in Tregs (34–36). We found that Foxp3 and permissive Ac-H3K9 had an almost complete overlap in the nuclei of WT Tregs by confocal assay, indicating the correlation between Foxp3 binding and Ac-H3K9 modification. However, Tregs of CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre mice had less overlap of Foxp3 and Ac-H3K9 levels (Fig. 6d and e), suggesting that CBP and p300 are recruited by Foxp3 to the Foxp3 targeting gene locus and collaboratively regulate gene transcription.

FIG 6.

CBP and p300 cooperatively regulate Treg function. (a) Representative images of endogenous Foxp3 (green) colocalization with CBP or p300 in nuclei of Tregs; images are representative of at least 30 Treg cells from Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Sorted CD4+ YFP+ cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with primary Abs (to Foxp3, CBP, or p300), followed by FITC- or PE-conjugated secondary Ab plus DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) nuclear stain, and analyzed by confocal microscopy (magnification, ×63). (b and c) 293T cells were transfected for 48 h with expression vectors for Foxp3, expression vectors for Foxp3 and CBP, expression vectors for Foxp3 and p300, or expression vectors for Foxp3, CBP, and p300 or with empty vector (EV); EV was added to ensure equal DNA amounts. (b) Western blots with Ab against Foxp3 or acetylated-Foxp3 (AcK31). Lane 1, Foxp3 plus EV; lane 2, Foxp3 plus CBP; lane 3, Foxp3 plus p300; lane 4, Foxp3 plus CBP plus p300. Quantitation of bands was performed using Image-J software, and the ratio of Ac-Foxp3 to total Foxp3 is shown. (c) Oligonucleotide pulldowns in which biotin-labeled oligonucleotides representing Foxp3 binding site sequences were incubated with Foxp3 plus EV (lane 1), Foxp3 plus CBP (lane 2), Foxp3 plus p300 (lane 3), Foxp3 plus CBP plus p300 (lane 4), or EV (lane 5) and with β-actin loading control. Data are representative of the results of 3 independent experiments. (d) Representative confocal images showing endogenous Foxp3 colocalized with acetylated-H3K9 (Ac-H3K9; green) in the nuclei of Tregs. Images are representative of at least 10 cells from CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3cre mice or littermates. (e) Representative signal intensity profiles of Foxp3 (red line) and Ac-H3K9 (green line), showing that Tregs from CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3cre mice had weaker Foxp3-Ac-H3K9 overlap than littermates. rel., relative.

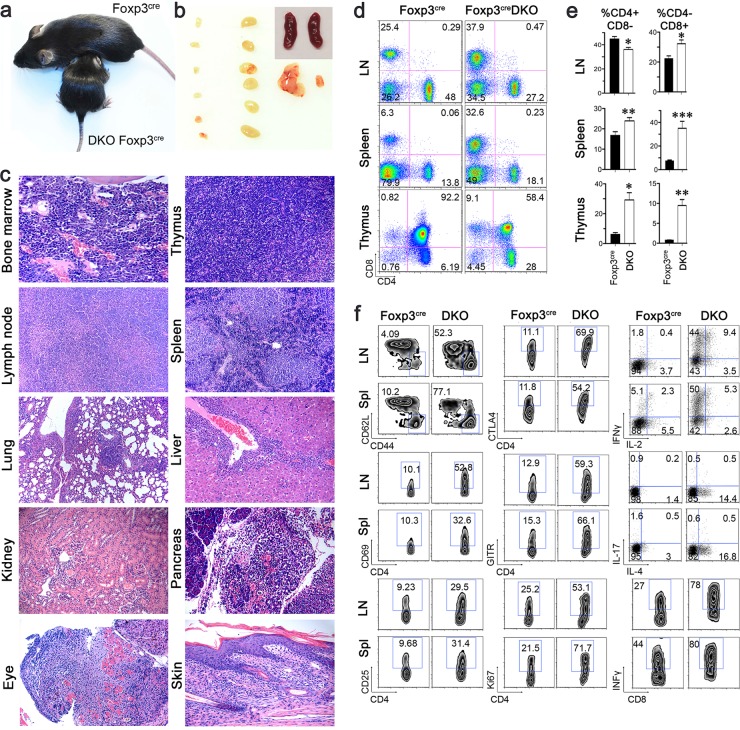

CBP and p300 cooperatively and distinctly regulate important Treg function factors.

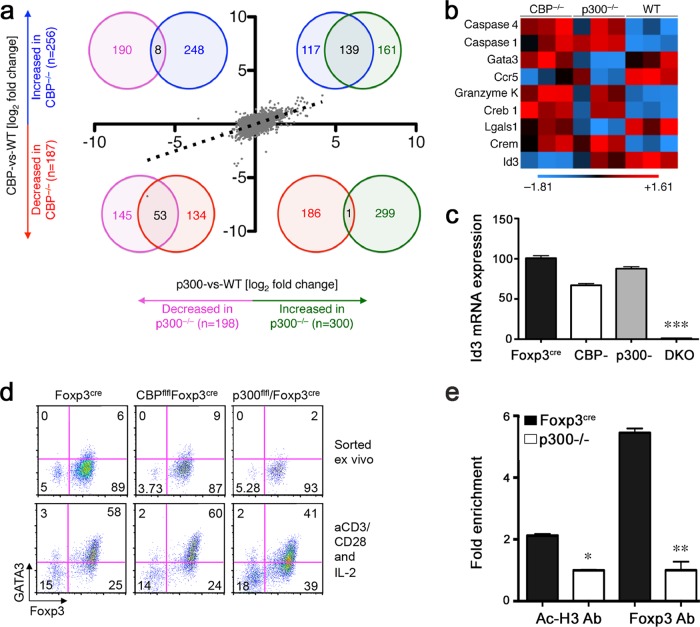

To identify genes regulated by p300 and/or CBP in Tregs, we undertook expression profiling using Affymetrix oligonucleotide arrays. The Treg gene expression profiles of CBPfl/fl/Foxp3cre and p300fl/fl/Foxp3cre mice showed a high degree of similarity (Spearman correlation, r = 0.583; P < 0.0001), indicating that loss of either p300 or CBP led to numerous overlapping alterations in gene expression (Fig. 7a). These data suggest that control of Treg functions by p300 and that by CBP are some extent redundant. We noted that 300 and 256 genes were upregulated and that 198 and 187 genes were downregulated in p300fl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre and CBPfl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs compared to WT Tregs, respectively. CBPfl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre and p300fl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs had 33.3% (139/417) and 16% (53/332) of their genes either up- or downregulated compared to Foxp3YFP-cre control results, respectively. In contrast, overlap between probes was minimal among genes upregulated by loss of p300 but downregulated by loss of CBP (0.2%, 1/486) and vice versa (1.8%, 8/446). (Fig. 7a; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Among the probes differentially expressed compared to controls, we noted several genes relevant to Treg biology (Fig. 7b), most of which (e.g., Id3) were decreased in level in Tregs from both CBPfl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre and p300fl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre mice. However, expression of some genes, e.g., Gata3, was selectively repressed in p300-deficient Tregs.

FIG 7.

CBP and p300 have overlapping but also distinct functions in Tregs. (a) Comparison of CBPfl/fl Foxp3cre (CBP−/−) and p300fl/fl Foxp3cre (p300−/−) RNA expression by microarray analysis (430a 2.0; Affymetrix). Data are shown as fold changes in RNA expression with respect to a shared WT control measured during the same experiment. A Spearman correlation curve is indicated by the dotted line (r = 0.583; P < 0.0001). Significance in RNA expression was determined by ANOVA (P = 0.05; Storey false-discovery rate, 0.1) and a fold change level of ≥1.5× (log2, 0.5849). The numbers of significantly different probes are overlaid as Venn diagrams and indicate much higher degrees of overlap if both p300 and CBP are upregulated or downregulated (33.3% or 16%, respectively). In contrast, overlap between probes was minimal among genes upregulated by loss of p300 and downregulated by loss of CBP (0.2%) and vice versa (1.8%). Red and blue circles represent decreased and increased gene expression in CBP−/− Tregs, respectively, and purple and green circles represent decreased and increased gene expression in p300−/− Treg cells. (b) Heat map showing synergistic but also differential control of Treg-associated genes. Abbreviations: Gata3, GATA binding protein 3; Ccr5, chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5; Creb, cAMP-responsive element binding protein; Lgals1, lectin, galactose binding, soluble 1; Crem, cAMP-responsive element modulator; Id3, inhibitor of DNA binding 3. Microarray data are from 3 mice/group. (c) qPCR showed Id3 expression in Tregs sorted from CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre, p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre, and CBPfl/fl p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Data were normalized to 18S. (d) Flow cytometry comparing levels of CD4+ Foxp3+ Gata+ expression in Tregs from CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre and p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice that, after being sorted as CD4+ YFP+ cells, were stimulated with plate-bound CD3/CD28 MAbs plus IL-2 for 24 h. Cells were gated on CD4. Data are representative of the results of 3 independent experiments. (e) Acetylated-H3 and Foxp3 binding to the CNS2 region as determined by ChIP-qPCR. CD4+ CD25+ Tregs were isolated from Foxp3YFP-cre and p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and stimulated with PMA-ionomycin for 2 h, and nuclear extracts were subjected to ChIP assay by pulling down with anti-AcH3, anti-Foxp3, or IgG Abs. Fold enrichment over IgG results is shown. Data are representative of the results of 2 independent experiments.

The Id3 DNA-binding inhibitor is a transcription factor involved in Treg production (37). Young Id3−/− mice have decreased proportions and numbers of Tregs and develop T cell-dependent autoimmune-like Sjogren's syndrome (37, 38). Both young and old Id3−/− mice have impaired suppressive activity (37). Our microarray data showed Id3 at lower levels in Tregs of both CBPfl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre and p300fl/fl/Foxp3YFP-cre mice. Analysis by qPCR confirmed this observation and showed drastically reduced levels in CBP/p300 double-knockout mice (Fig. 7c). Thus, Id3 is an example of a gene that CBP and p300 regulate synergistically in Tregs, and CBP cannot replace p300 for this function and vice versa.

Gata3, an important functional partner of Foxp3 in Tregs (39), is required for the maintenance of high levels of Foxp3 expression and promotes Treg accumulation at inflammatory sites (40). Gata3 is upregulated and forms a complex with Foxp3 upon TCR stimulation of Treg cells (39). Our microarray analysis showed that, compared to controls, CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs had similar Gata3 levels but p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre Tregs had lower Gata3 levels (Fig. 7b). Consistent with the gene expression patterns, p300-deficient Tregs had markedly lower Gata3 protein expression but CBP-deficient Tregs had comparable Gata3 protein levels after TCR stimulation for 24 h (Fig. 7d). To identify the possible mechanisms involved in causing the lower Gata3 levels in p300-deficient Tregs, we performed ChIP assays with acetylated H3 and Foxp3 antibodies. P300-deficient Tregs had lower acetylated H3 levels and lower levels of Foxp3 binding on a known Foxp3 binding site of the Gata3 promoter (39) (Fig. 7e). To test whether CBP or p300 affected the Gata3 protein level, given their effects on the Foxp3 protein level, expression vectors that included CBP or p300 plus Gata3 were cotransfected into 293T cells for 48 h. Neither CBP nor p300 altered the Gata3 protein level (data not shown). These data indicate that p300 regulates Gata3 production in Tregs by acting at the level of Gata3 locus chromatin structure and Foxp3 binding ability.

DISCUSSION

Our studies revealed critical roles of two closely related HATs, CBP and p300, in control of Treg production and function. Combined CBP and p300 deletion in Tregs resulted in significant reductions in expression of Foxp3 and Treg suppressive function, leading to ongoing T cell activation and proliferation, widespread mononuclear infiltration, and death from autoimmunity within 3 weeks of birth. CBP and p300 control Treg development through at least 3 mechanisms. First, there are gene dose-dependent effects in which the total amount of CBP and p300 genes in Tregs is inversely correlated with disease severity in mice. Tregs without CBP and p300 rapidly develop severe autoimmunity comparable to that seen in scurfy mice; Tregs with loss of three alleles of CBP and p300 develop relatively severe autoimmunity but at a slower pace; and Tregs with two alleles of CBP and p300 do not develop overt disease. Second, CBP and p300 redundantly regulate Treg production under steady-state conditions. Third, CBP and p300 use different mechanisms to regulate Foxp3 protein level and Treg stability under activating conditions.

Tregs lose Foxp3 expression after transfer to lymphopenic hosts (41) or under inflammatory conditions (42). Here, we found that both CBP and p300 control Foxp3+ Treg stability and function during inflammation. While p300 is normally expressed in CBPfl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice and CBP is normally expressed in p300fl/fl Foxp3YFP-cre mice, it appears that each cannot compensate for a lack of the other under lymphopenic or inflammatory conditions. These findings suggest nonredundant roles of CBP and p300 in regulating similar aspects of Treg biology. CNS2 at the Foxp3 locus encodes information associated with Treg stability. CNS2 is required for sustained Foxp3 expression in the progeny of dividing cells (43). Stimulation with IL-2 plus TCR promotes CREB/ATF binding to the Foxp3 CNS2 region, thus driving Foxp3 transcription, whereas methylated CpG islands interfere with CREB/ATF binding and inhibit Foxp3 expression (25). Here, we found that CBP deletion in Treg does not affect CpG island demethylation but that CBP enhances pCREB DNA binding to the CNS2 region, thus promoting Foxp3 expression upon TCR stimulation. Additionally, CD25hi Tregs are known to exhibit a more stable phenotype than CD25low Tregs (41), and CD25low Tregs are prone to lose Foxp3 and produce IL-17 in arthritic mice after adoptive transfer (44). We found that CBP-deficient Tregs had lower CD25 levels and produced more IL-17A after stimulation with TCR plus IL-6, demonstrating that CBP is a critical determinant in maintaining Treg homoeostasis upon inflammatory challenge.

Gata3 is not required for maintenance of Treg homeostasis under steady-state conditions but is critical for Tregs to sustain high levels of Foxp3 and Treg function, stability, and accumulation at inflammation sites (45). The binding of Gata3 to the CNS2 element of the Foxp3 locus is a key mechanism by which Gata3 controls Treg stability under inflammation conditions (40). We found that loss of p300, but not loss of CBP, in Tregs impaired Gata3 expression. Our results support a model whereby p300 promotes Gata3 expression, leading to more Gata3 binding to the Foxp3 CNS2 region, which ultimately enhances Treg stability. Greater Foxp3 levels in turn drive Gata3 expression. Thus, there is a positive-feedback loop by which p300, Foxp3, and Gata3 function to maintain and to augment Treg stability. Therefore, DNA hypomethylation combined with the presence of coactivators CBP and p300 is important for maintaining the Treg lineage and Foxp3-containing transcriptional complexes in inflammatory or pathogenic environments.

Foxp3 associates with CBP and p300. Thus, in addition to the direct acetylation on Foxp3 itself, CBP and p300 can provide a permissive environment for Foxp3-associated chromatin remodeling and can interact with Foxp3 to regulate gene expression. Our studies showed that Ac-H3K9 is associated with Foxp3 in Tregs and that levels of several Treg signature markers (e.g., CTLA4, GITR, and CD25) were significantly impaired in DKO Tregs. The promoters of these contain Foxp3 binding sites, so it is reasonable that CBP and p300 epigenetically regulate Foxp3 to promote their gene expression. However, it is currently very difficult to experimentally confirm additional specific histone codes and/or target genes, due to the very limited numbers of purified Tregs available from DKO mice (∼150 DKO mice are needed to obtain 1 million Tregs by cell sorting).

Within the B cell lineage, individual CBP or p300 deletion performed before the pro-B cell stage reduced peripheral B cell numbers only partially, whereas inactivation of CBP and p300 was not tolerated by peripheral B cells (46), indicating the effects of limiting the amount of CBP and p300 genes in different cell types. CBP proved somewhat more important than p300 when it was lost after the pro-B stage (46). In the current study, we found that p300 plays a more important role than CBP in Treg development. One explanation could be that CBP and p300 play different roles in different cell types. Another possible explanation could be that the total amount of CBP and p300 genes in Tregs is limiting and that the amount of p300 is higher than CBP in Tregs. This could provide a rationale to design specific CBP or p300 inhibitors for targeting in different cell types.

Thymic and peripheral Treg numbers were markedly decreased when both CBP and p300 were deleted. Over 400 different proteins are reported to interact physically or functionally with CBP and p300 (47). Consistent with their roles as coactivators, CBP and p300 can interact with, and acetylate, many transcription factors that are important for Foxp3 expression, including NFAT, STAT1, Foxo1, Foxo3, NF-κB (c-Rel and p65), Runx1, and Stat5 (30, 31, 48–50). In agreement with a previous study (31), we found using luciferase assays that p65 could promote Foxp3 promoter activity, whereas Runx1 alone did not increase Foxp3 production. We extended these findings by showing that CBP and p300 could further increase the ability of p65 or Runx1 to increase Foxp3 expression. Thus, CBP and p300 can indirectly promote Foxp3 generation by enhancing related transcription factor activities affecting protein stability, DNA binding, and transactivation ability. In addition to promoting the actions of transcription factors, such transcription factors can recruit CBP and p300 to the Foxp3 locus to help open the chromatin structure and promote Foxp3 transcription.

Apart from their thymic development, Tregs can differentiate from CD4+ CD25− T cells in the periphery. Epigenetic alterations at the Foxp3 locus are important for such induced Treg (iTreg) stability and function. For example, retinoic acid, the vitamin A metabolite, can enhance transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-mediated histone acetylation on the STAT6 binding sites of the Foxp3 promoter and promote TGF-β-mediated iTreg production (51). Retinoic acid also induces H4 acetylation at the Foxp3 locus and Foxp3 expression in naive CD4+ CD25− T cells (52). However, the roles of HATs in this process are still unclear. We expected that CBP and p300 could be important in helping retinoic acid to open the Foxp3 chromatin structure, based on parallel observations of the existence of a retinoic acid/CBP/p300 complex (53) and given the effects of CBP/p300 on STAT6 (54). Lymphocytes lacking both CBP and p300 cannot develop normally (11), limiting our ability to examine the direct roles that CBP and p300 play in iTreg production. However, we found that naive CD4+ CD25− Teff cells treated with a p300 inhibitor showed impaired conversion to CD4+ Foxp3+ iTreg cells (19). This impaired peripheral conversion was correlated with lower H3 acetylation of the Foxp3 CNS1 region (19), which is critical for iTreg production. In addition, we found that CBP and p300 synergistically regulate Id3 gene level, and Id3 was shown to be important for iTreg production (37). Hence, CBP and p300 regulate several factors important for iTreg production.

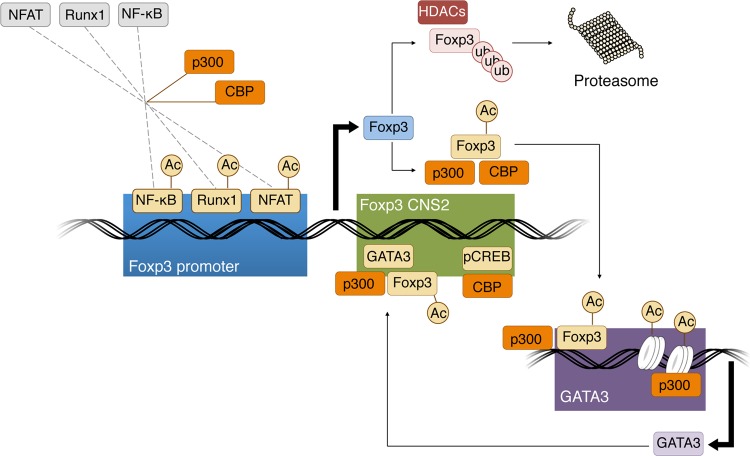

Collectively, our studies show that both epigenetic and transcriptional events maintain Treg stability under conditions of inflammatory stimuli (Fig. 8). Overall, CBP and p300 form a complex network with other transcription factors and function within this complex as master regulators of Foxp3+ Treg generation and cell survival. These properties make CBP and p300 interesting drug targets in efforts to overcome mechanisms of immune escape in which cancers can recruit or induce de novo Tregs locally in the tumor environment, as we have recently shown (19). However, our data also provide a note of caution, in that p300 inhibitors would need either to be gene specific or to show only partial inhibition of both p300 and CBP if patients were to avoid significant risk for induction of autoimmunity. Therefore, our results provide new mechanistic insights that will likely aid in the design of therapies to target Treg cells, especially with relevance to cancer immunotherapy.

FIG 8.

Working model of how CBP and p300 regulate Foxp3 production, stability, and function in Treg cells. CBP and p300 acetylate several transcription factors that are important for Foxp3 production, including NFAT, Runx1, and NF-κB; acetylation increases their transcriptional activities, thereby increasing Foxp3 transcription. Translated Foxp3 protein can be stabilized by acetylation through CBP and p300; Foxp3 acetylation conveys protection against K48 polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation and increases Foxp3 DNA binding. Furthermore, p300 is recruited to the Gata3 promoter by Foxp3, creating an open chromatin structure and promoting Gata3 gene transcription. Lastly, p300 and CBP promote Gata3 and pCREB binding to the Foxp3 CNS2 region, respectively, and thus maintain stable Foxp3 expression and Treg stability.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to W.W.H. (AI073489 and AI095276) and to U.H.B. (AI095353).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00919-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth SY, Denu JM, Allis CD. 2001. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:81–120. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Tang Y, Cole PA, Marmorstein R. 2008. Structure and chemistry of the p300/CBP and Rtt109 histone acetyltransferases: implications for histone acetyltransferase evolution and function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:741–747. 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmorstein R. 2001. Structure of histone acetyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol. 311:433–444. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan HM, La Thangue NB. 2001. p300/CBP proteins: HATs for transcriptional bridges and scaffolds. J. Cell Sci. 114:2363–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao TP, Oh SP, Fuchs M, Zhou ND, Ch'ng LE, Newsome D, Bronson RT, Li E, Livingston DM, Eckner R. 1998. Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300. Cell 93:361–372. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Naruse I, Hongo T, Xu M, Nakahata T, Maekawa T, Ishii S. 2000. Extensive brain hemorrhage and embryonic lethality in a mouse null mutant of CREB-binding protein. Mech. Dev. 95:133–145. 10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McManus KJ, Hendzel MJ. 2003. Quantitative analysis of CBP- and P300-induced histone acetylations in vivo using native chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:7611–7627. 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7611-7627.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Wang L, Zhao K, Thompson PR, Hwang Y, Marmorstein R, Cole PA. 2008. The structural basis of protein acetylation by the p300/CBP transcriptional coactivator. Nature 451:846–850. 10.1038/nature06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henry RA, Kuo YM, Andrews AJ. 2013. Differences in specificity and selectivity between CBP and p300 acetylation of histone H3 and H3/H4. Biochemistry 52:5746–5759. 10.1021/bi400684q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma H, Nguyen C, Lee KS, Kahn M. 2005. Differential roles for the coactivators CBP and p300 on TCF/beta-catenin-mediated survivin gene expression. Oncogene 24:3619–3631. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasper LH, Fukuyama T, Biesen MA, Boussouar F, Tong C, de Pauw A, Murray PJ, van Deursen JM, Brindle PK. 2006. Conditional knockout mice reveal distinct functions for the global transcriptional coactivators CBP and p300 in T-cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:789–809. 10.1128/MCB.26.3.789-809.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuyama T, Kasper LH, Boussouar F, Jeevan T, van Deursen J, Brindle PK. 2009. Histone acetyltransferase CBP is vital to demarcate conventional and innate CD8+ T-cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:3894–3904. 10.1128/MCB.01598-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki H, Eckner R, Yao TP, Taira K, Chiu R, Livingston DM, Yokoyama KK. 1998. Distinct roles of the co-activators p300 and CBP in retinoic-acid-induced F9-cell differentiation. Nature 393:284–289. 10.1038/30538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, Yasayko SA, Wilkinson JE, Galas D, Ziegler SF, Ramsdell F. 2001. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat. Genet. 27:68–73. 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khattri R, Kasprowicz D, Cox T, Mortrud M, Appleby MW, Brunkow ME, Ziegler SF, Ramsdell F. 2001. The amount of scurfin protein determines peripheral T cell number and responsiveness. J. Immunol. 167:6312–6320. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu B, Tahk S, Yee KM, Fan G, Shuai K. 2010. The ligase PIAS1 restricts natural regulatory T cell differentiation by epigenetic repression. Science 330:521–525. 10.1126/science.1193787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, Schlawe K, Chang HD, Bopp T, Schmitt E, Klein-Hessling S, Serfling E, Hamann A, Huehn J. 2007. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 5:e38. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bettini ML, Pan F, Bettini M, Finkelstein D, Rehg JE, Floess S, Bell BD, Ziegler SF, Huehn J, Pardoll DM, Vignali DA. 2012. Loss of epigenetic modification driven by the Foxp3 transcription factor leads to regulatory T cell insufficiency. Immunity 36:717–730. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Wang L, Predina J, Han R, Beier UH, Wang LC, Kapoor V, Bhatti TR, Akimova T, Singhal S, Brindle PK, Cole PA, Albelda SM, Hancock WW. 2013. Inhibition of p300 impairs Foxp3+ T regulatory cell function and promotes antitumor immunity. Nat. Med. 19:1173–1177. 10.1038/nm.3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubtsov YP, Rasmussen JP, Chi EY, Fontenot J, Castelli L, Ye X, Treuting P, Siewe L, Roers A, Henderson WR, Jr, Muller W, Rudensky AY. 2008. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity 28:546–558. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Wang L, Han R, Beier UH, Hancock WW. 2012. Two lysines in the forkhead domain of foxp3 are key to T regulatory cell function. PLoS One 7:e29035. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koh KP, Sundrud MS, Rao A. 2009. Domain requirements and sequence specificity of DNA binding for the forkhead transcription factor FOXP3. PLoS One 4:e8109. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Liu Y, Beier UH, Han R, Bhatti TR, Akimova T, Hancock WW. 2013. Foxp3+ T-regulatory cells require DNA methyltransferase 1 expression to prevent development of lethal autoimmunity. Blood 121:3631–3639. 10.1182/blood-2012-08-451765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battke F, Symons S, Nieselt K. 2010. Mayday–integrative analytics for expression data. BMC Bioinformatics 11:121. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HP, Leonard WJ. 2007. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J. Exp. Med. 204:1543–1551. 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH. 1993. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature 365:855–859. 10.1038/365855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardinaux JR, Notis JC, Zhang Q, Vo N, Craig JC, Fass DM, Brennan RG, Goodman RH. 2000. Recruitment of CREB binding protein is sufficient for CREB-mediated gene activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1546–1552. 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1546-1552.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krenger W, Rossi S, Piali L, Hollander GA. 2000. Thymic atrophy in murine acute graft-versus-host disease is effected by impaired cell cycle progression of host pro-T and pre-T cells. Blood 96:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belhacéne N, Gamas P, Gonçalvès D, Jacquin M, Beneteau M, Jacquel A, Colosetti P, Ricci JE, Wakkach A, Auberger P, Marchetti S. 2012. Severe thymic atrophy in a mouse model of skin inflammation accounts for impaired TNFR1 signaling. PLoS One 7:e47321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitoh A, Ono M, Naoe Y, Ohkura N, Yamaguchi T, Yaguchi H, Kitabayashi I, Tsukada T, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, Taniuchi I, Sakaguchi S. 2009. Indispensable role of the Runx1-Cbfbeta transcription complex for in vivo-suppressive function of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity 31:609–620. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruan Q, Kameswaran V, Tone Y, Li L, Liou HC, Greene MI, Tone M, Chen YH. 2009. Development of Foxp3(+) regulatory t cells is driven by the c-Rel enhanceosome. Immunity 31:932–940. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Loosdregt J, Vercoulen Y, Guichelaar T, Gent YY, Beekman JM, van Beekum O, Brenkman AB, Hijnen DJ, Mutis T, Kalkhoven E, Prakken BJ, Coffer PJ. 2010. Regulation of Treg functionality by acetylation-mediated Foxp3 protein stabilization. Blood 115:965–974. 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon HS, Lim HW, Wu J, Schnolzer M, Verdin E, Ott M. 2012. Three novel acetylation sites in the Foxp3 transcription factor regulate the suppressive activity of regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 188:2712–2721. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Y, Josefowicz SZ, Kas A, Chu TT, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. 2007. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature 445:936–940. 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan F, Yu H, Dang EV, Barbi J, Pan X, Grosso JF, Jinasena D, Sharma SM, McCadden EM, Getnet D, Drake CG, Liu JO, Ostrowski MC, Pardoll DM. 2009. Eos mediates Foxp3-dependent gene silencing in CD4+ regulatory T cells. Science 325:1142–1146. 10.1126/science.1176077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katoh H, Qin ZS, Liu R, Wang L, Li W, Li X, Wu L, Du Z, Lyons R, Liu CG, Liu X, Dou Y, Zheng P, Liu Y. 2011. FOXP3 orchestrates H4K16 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation for activation of multiple genes by recruiting MOF and causing displacement of PLU-1. Mol. Cell 44:770–784. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maruyama T, Li J, Vaque JP, Konkel JE, Wang W, Zhang B, Zhang P, Zamarron BF, Yu D, Wu Y, Zhuang Y, Gutkind JS, Chen W. 2011. Control of the differentiation of regulatory T cells and T(H)17 cells by the DNA-binding inhibitor Id3. Nat. Immunol. 12:86–95. 10.1038/ni.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Dai M, Zhuang Y. 2004. A T cell intrinsic role of Id3 in a mouse model for primary Sjogren's syndrome. Immunity 21:551–560. 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudra D, deRoos P, Chaudhry A, Niec RE, Arvey A, Samstein RM, Leslie C, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, Rudensky AY. 2012. Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nat. Immunol. 13:1010–1019. 10.1038/ni.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Su MA, Wan YY. 2011. An essential role of the transcription factor GATA-3 for the function of regulatory T cells. Immunity 35:337–348. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komatsu N, Mariotti-Ferrandiz ME, Wang Y, Malissen B, Waldmann H, Hori S. 2009. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: a committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:1903–1908. 10.1073/pnas.0811556106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, Penaranda C, Martinez-Llordella M, Ashby M, Nakayama M, Rosenthal W, Bluestone JA. 2009. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 10:1000–1007. 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. 2010. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature 463:808–812. 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Komatsu N, Okamoto K, Sawa S, Nakashima T, Oh-Hora M, Kodama T, Tanaka S, Bluestone JA, Takayanagi H. 2014. Pathogenic conversion of Foxp3(+) T cells into TH17 cells in autoimmune arthritis. Nat. Med. 20:62–68. 10.1038/nm.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wohlfert EA, Grainger JR, Bouladoux N, Konkel JE, Oldenhove G, Ribeiro CH, Hall JA, Yagi R, Naik S, Bhairavabhotla R, Paul WE, Bosselut R, Wei G, Zhao K, Oukka M, Zhu J, Belkaid Y. 2011. GATA3 controls Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell fate during inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:4503–4515. 10.1172/JCI57456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu W, Fukuyama T, Ney PA, Wang D, Rehg J, Boyd K, van Deursen JM, Brindle PK. 2006. Global transcriptional coactivators CREB-binding protein and p300 are highly essential collectively but not individually in peripheral B cells. Blood 107:4407–4416. 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bedford DC, Kasper LH, Fukuyama T, Brindle PK. 2010. Target gene context influences the transcriptional requirement for the KAT3 family of CBP and p300 histone acetyltransferases. Epigenetics 5:9–15. 10.4161/epi.5.1.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudra D, Egawa T, Chong MM, Treuting P, Littman DR, Rudensky AY. 2009. Runx-CBFbeta complexes control expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 in regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 10:1170–1177. 10.1038/ni.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. 2007. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 178:280–290. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouyang W, Beckett O, Ma Q, Paik JH, DePinho RA, Li MO. 2010. Foxo proteins cooperatively control the differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 11:618–627. 10.1038/ni.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takaki H, Ichiyama K, Koga K, Chinen T, Takaesu G, Sugiyama Y, Kato S, Yoshimura A, Kobayashi T. 2008. STAT6 inhibits TGF-beta1-mediated Foxp3 induction through direct binding to the Foxp3 promoter, which is reverted by retinoic acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283:14955–14962. 10.1074/jbc.M801123200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang SG, Lim HW, Andrisani OM, Broxmeyer HE, Kim CH. 2007. Vitamin A metabolites induce gut-homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 179:3724–3733. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dietze EC, Troch MM, Bowie ML, Yee L, Bean GR, Seewaldt VL. 2003. CBP/p300 induction is required for retinoic acid sensitivity in human mammary cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 302:841–848. 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gingras S, Simard J, Groner B, Pfitzner E. 1999. p300/CBP is required for transcriptional induction by interleukin-4 and interacts with Stat6. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:2722–2729. 10.1093/nar/27.13.2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.