Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between neighborhood convenience stores and diet outcomes for 20 years of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study.

Methods. We used dietary data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study years 1985–1986, 1992–1993, and 2005–2006 (n = 3299; Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA) and geographically and temporally matched neighborhood-level food resource and US Census data. We used random effects repeated measures regression to estimate associations between availability of neighborhood convenience stores with diet outcomes and whether these associations differed by individual-level income.

Results. In multivariable-adjusted analyses, greater availability of neighborhood convenience stores was associated with lower diet quality (mean score = 66.3; SD = 13.0) for participants with lower individual-level income (b = −2.40; 95% CI = −3.30, −1.51); associations at higher individual-level income were weaker. We observed similar associations with whole grain consumption across time but no statistically significant associations with consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, snacks, processed meats, fruits, or vegetables.

Conclusions. The presence of neighborhood convenience stores may be associated with lower quality diets. Low-income individuals may be most sensitive to convenience store availability.

Although evidence from interventions and randomized controlled trials is rare, observational epidemiological studies suggest that fruit, vegetable, and whole grain consumption are cardioprotective1–5 and that intake of processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs), and snack foods are associated with an elevated risk of cardiometabolic health-related outcomes.6–12 In addition to single foods, poor adherence to nutritional guidelines and lower diet quality are associated with obesity, weight gain, and other cardiometabolic outcomes,13–17 with minorities and individuals of low socioeconomic status (SES) particularly affected.18–20

A majority of behavioral interventions to reduce SSB and snack food intake and to increase diet quality have not been successful.21–24 Thus, researchers have called for policies and initiatives to modify the retail food environment to provide healthy options for consumers,25–28 including a focus on convenience stores and corner stores.29 Several studies suggest that convenience stores and small urban stores provide energy-dense, nutrient-poor snacks and sugar-sweetened drinks and offer few healthy snack options and other nutritious food items (e.g., fruit, vegetables, whole grains).30–36 Studies that have examined access to convenience stores in relation to obesity-related and diet outcomes provide mixed findings.37–49 Furthermore, with few exceptions,46–49 previous studies are cross-sectional37–47,49 or do not examine potential differences by SES.37–45,48 In addition, none have focused on racially diverse young- to middle-aged adults across a variety of metropolitan areas.

To address these gaps, we used longitudinal physical examination–based, anthropometric, and biomarker data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study spanning 20 years. Using temporally and geographically matched neighborhood food outlet locations, we estimated the association between diet and percentage of convenience stores within 3 kilometers of CARDIA respondents’ homes. To address the potential role of convenience stores in socioeconomic disparities in cardiometabolic risk factors, we explicitly examined how associations between percentage of neighborhood convenience stores, diet quality, and consumption of single food items differ by individual-level SES.

METHODS

CARDIA is a prospective study of the development of cardiometabolic disease among younger adults. In 1985–1986, 5115 Black and White men and women aged 18 to 30 years were recruited to attain an approximately balanced representation of age (18–24 or 25–30 years), race (White or Black), gender, and education (≤ high school or > high school) from 4 metropolitan study centers (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA). Follow-up examinations were conducted in 1987–1988 (year 2), 1990–1991 (year 5), 1992–1993 (year 7), 1995–1996 (year 10), 2000–2001 (year 15), 2005–2006 (year 20), and 2010–2011 (year 25), with retention rates of 91%, 86%, 81%, 79%, 74%, 72%, and 72%, respectively.

We used a geographic information system to geographically and temporally link time-varying, neighborhood-level food resources (e.g., restaurants, supermarkets) and US Census data to CARDIA respondents’ residential addresses, capturing all food outlets within a 5-mile radius of each individual at each examination year.

Dietary Assessment

We assessed diet at examination years 0, 7, and 20 using the CARDIA diet history,50 an interviewer-administered, open-ended validated questionnaire about dietary intake in the past month.51 We assigned diet history data to 166 food groups using a food-grouping system created by the University of Minnesota Nutrition Coordinating Center. CARDIA investigators further collapsed these food groups into 46 food groups, as previously described.20,52,53 We calculated food group intake as servings per day.

Using these data, we considered a range of diet exposure variables, including dietary patterns and food groups, to identify which components of participants’ diets were significantly affected by neighborhood availability of convenience stores.

Dietary Patterns

Details of the construction of the CARDIA a priori diet quality score have been published.20,52,53 In brief, we used the a priori diet quality score, which categorizes the 46 food groups as beneficial (n = 20), adverse (n = 13), or neutral (n = 13) on the basis of their hypothesized relationships with health.20,52 We categorized consumption of adverse and beneficial foods by quintiles ranging from lowest to highest consumption and then gave it a score of 0 to 4 for positively rated food groups and 4 to 0 for negatively rated food groups; for example, intake in the highest quintile of beneficial foods (e.g., whole grains, fruits, vegetables) received a score of 4, and intake in the highest quintile of adverse foods (e.g., SSBs, ASBs, salty snacks, processed meat) received a score of 0.

This scoring system resulted in a final a priori diet quality score with a theoretical maximum of 132 and a mean of 63.3 (SD = 13; range = 24–107) at year 0 in CARDIA, with a higher score indicating higher diet quality.

Food Groups

We created several specific food groups that we considered relevant to our study: fruits (not including juice), vegetables (not including juice), whole grains, processed meats, snacks (including chips, meat-based savory snacks, and popcorn), desserts (including baked goods and frozen dairy desserts), SSBs (sugar-sweetened fruit drinks, soft drinks, and water), and ASBs (artificially sweetened fruit drinks, soft drinks, and water).

We examined all food and beverage groups separately as weekly servings.

Availability of Neighborhood Resources

We obtained food resource data from the Dun & Bradstreet Duns Market Identifiers File (food store and restaurant Standard Industrial Classification categories; Dun & Bradstreet, Inc., Short Hills, NJ),54 a commercial data set of US businesses. We classified food resources according to primary 8-digit Standard Industrial Classification codes at years 7 to 25 and a combination of 4-digit Standard Industrial Classification codes and matched business names at year 0 (Table A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We calculated the count of each type of food resource within a 3-kilometer distance along the street network around participant homes. We selected a 3-kilometer network buffer because it represents availability of neighborhood food resources relative to the street network and reflects the distance and manner participants would travel to convenience stores via the street network.55,56

Our primary exposure variable was the percentage of convenience stores relative to total food stores and restaurants (within a 3-km network buffer). Our rationale for this measure was to address convenience stores within the context of other neighborhood retail food options, regardless of whether they were considered healthy or unhealthy options. Thus, our measure represents the full range of retail food outlet choices in the neighborhood rather than the absolute count of convenience stores.

Covariates

We collected self-reported individual-level sociodemographic information at baseline using a standardized questionnaire, including age, gender, and race (Black, White). We collected current educational attainment (in years) at all examination years and income categories at each examination starting at year 5.

We created a community-level neighborhood deprivation score, with a higher score indicating greater neighborhood deprivation, using principle components analysis of 4 tract-level variables: (1) percentage of tract education less than high school at age 25 years, (2) education college or higher at age 25 years, (3) median household income, and (4) percentage of people with household incomes less than 150% of the federal poverty level (as determined by the Department of Health and Human Services) at each examination year.57 We defined population density as population per square kilometer within a 3-kilometer Euclidean buffer. We derived the county-level cost of living index from the Council for Community and Economic Research and spatially and temporally linked it to respondents’ residential locations.

Analytic Sample

We considered participants who were present for CARDIA year 0, 7, or 20 examinations eligible for this study (n = 5115). We excluded individuals with implausible dietary data (n = 213), missing dietary data (n = 534), and missing income or education data (n = 475); thus, our final longitudinal analysis sample included 3922 participants.

Food resource data were complete for all observations, so exclusion was unrelated to food resource data availability.

Statistical Analysis

We examined correlations between neighborhood-level variables as well as changes in the availability of food resources and sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample at CARDIA years 0 and 20 examinations using an analysis of variance test of difference. Because we observed small within-person temporal variability in the percentage of convenience stores, we used repeated measures random effects regression for all diet outcomes. Essentially, this model uses a series of cross-sectional data to estimate between-person changes over time (accounting for within-person correlation of serial measurements); thus, model estimates represent the average difference in diet outcomes for each unit of convenience store availability over the 20-year period.

On the basis of the normal distribution of diet outcomes, we used linear regression for analyses of dietary patterns and continuous food group outcomes (in separate models), including fruit, vegetables, whole grains, processed meats, and snack foods. For food groups with greater than 20% nonconsumption (SSB and ASB consumption), we used 2-step econometric models,58–60 which account for the high percentage of meaningful zeros.

We used these 2-step models to predict the actual amount consumed across the full sample. The first equation is a random effects probit regression that estimates the probability of consuming a beverage across the full sample. The second equation is a random effects linear regression model that estimates the amount of beverage consumption of consumers only (i.e., conditional on consumption). The coefficients from the second equation (linear model among consumers only) were weighted by the coefficients from the first equation (probit model among full sample); thus, predicted values from the 2-step model represent weighted means of the amount of unconditional (i.e., regardless of consumption) beverage consumption for the full sample. We obtained SEs by bootstrapping with 1000 replications.

We tested linearity of exposures using 2 approaches: adding a quadratic term to linear regression models and classifying our exposure using categorical terms. These analyses indicated that associations between convenience stores and diet outcomes were often, but not always, nonlinear. To account for nonlinearity when present, and for consistency of presentation and ease of interpretability, we modeled food resource exposures categorically, using approximate quartile cutoff points: percentage of convenience stores relative to total food stores and restaurants (≤ 10%, 11%–20%, > 20%) and total count of food stores and restaurants (≤ 10, 11–99, ≥ 100 counts).

On the basis of their hypothesized relationships with the exposure and outcome, we adjusted for the following covariates in all models: individual-level age, gender, race (Black, White), baseline center, maximum educational attainment (completed elementary school, ≤ 3 years high school, 4 years high school, ≤ 3 years college, or ≥ 4 years college), community-level population density, cost of living (relative to a standard of 1 from years 1982–1984), total food stores and restaurants (≤ 10, 11–99, ≥ 100 counts), and time.

We were interested in whether the effect of convenience stores on diet was modified by individual-level SES. We tested for interaction by maximum-reported income (units of $10 000 from midpoint of category) by including a cross-product term in regression models. We used Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) for all analyses (xtreg for linear regression and xtprobit for binary regression) and covariate-specific associations (margins).

Sensitivity Testing

In sensitivity analyses, we compared our findings by individual-level SES with differences by neighborhood-level SES; therefore, we tested for interaction by neighborhood deprivation (continuous) by including a cross-product term in regression models (and adjusting for individual-level income). To determine whether results from our a priori diet quality score were robust to classification of diet, we also compared results with a different indicator of diet quality (i.e., Western vs prudent diet). To do so, we used using principle components analysis with orthogonal rotation to empirically derive 2 uncorrelated dietary patterns from the 46 food groups: 1 with high factor loadings of healthier foods, labeled “prudent,” and another with high factor loadings of unhealthier foods, labeled “Western.”52,53

In addition, we compared findings with 1-, 5-, and 8-kilometer network buffer sizes with our analyses with a priori diet quality score. In separate models, we examined a 3-way interaction by time and income (percentage of convenience stores × time × income) in relation to each outcome to justify our repeated measures approach to estimating changes across time. We adjusted for all individual- and neighborhood-level covariates in sensitivity analyses.

RESULTS

The a priori diet quality score increased by 7.0 ±11.6 points between years 0 and 20 (Table 1). Consumption of SSBs and desserts significantly decreased between years 0 and 20, and fruit, vegetable, processed meat, and ASB consumption significantly increased; consumption of snacks and whole grains did not change considerably across time. At the neighborhood level, counts of neighborhood convenience stores significantly increased between examination years, whereas counts of total food stores and restaurants and the percentage of neighborhood convenience stores did not change over time. The correlation between the percentage of neighborhood convenience stores (relative to total food stores and restaurants) and total food stores and restaurants was moderate and inverse (r = −0.35).

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Study Sample at Examination Years 0 (1985–1986) and 20 (2005–2006): Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study; Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; Oakland, CA

| Characteristic | Year 0 (1985–1986) | Year 20 (2005–2006)a | Change | P b |

| Baseline individual-level factors | ||||

| White, % | 52.4 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Age, y, mean ±SD | 25.0 ±3.6 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Male, % | 44.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Income, $, % | ||||

| < 35 000 | 53.4 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| 35 000–49 999 | 17.7 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| ≥ 50 000 | 29.9 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Education, % | ||||

| ≤ high school | 36.0 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Some college | 33.7 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| ≥ college graduate | 30.3 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| A priori diet quality score, mean ±SD | 63.3 ±13.0 | 70.6 ±12.7 | 7.0 ±11.6 | < .001 |

| Food or drink item, servings/wk | ||||

| Snacksc | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.1 (1.1) | .13 |

| Dessertsd | 1.0 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.2) | −0.2 (1.5) | < .001 |

| SSBse | 1.5 (2.0) | 0.9 (1.9) | −0.5 (2.3) | < .001 |

| Diet beveragesf | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.6 (1.7) | 0.2 (1.7) | < .001 |

| Fruit | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.9) | 0.4 (2.0) | < .001 |

| Vegetables | 2.5 (2.3) | 3.1 (2.5) | 0.6 (2.7) | < .001 |

| Whole grains | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.5) | 0.1 (1.9) | .2 |

| Processed meat | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.1 (1.2) | .002 |

| Neighborhood-level factors, mean ±SD | ||||

| Population densityg | 3481 ±2 213 | 2067 ±2 208 | −1 414 ±2 430 | < .001 |

| Cost of livingh | 1.05 ±0.06 | 1.15 ±0.22 | 0.10 ±0.19 | < .001 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Education at 25 y < high school, % | 29.9 | 16.4 | −13.5 | < .001 |

| Education at 25 y ≥ college, % | 22.3 | 31.8 | 9.5 | < .001 |

| Median household income, $, median ±SD | 15 291 ±6 504 | 51 940 ±24 927 | 36 649 ±23 799 | < .001 |

| Population < 150% FPL, % | 28.8 | 19.4 | −9.4 | < .001 |

| Convenience store count,i mean ±SD | 16.1 ±8.5 | 17.2 ±18.2 | 0.2 ±17.1 | .002 |

| Total food stores and restaurants count,i mean ±SD | 165 ±179.0 | 161 ±299.0 | −3.9 ±307.0 | .94 |

| Percentage of convenience stores,j mean ±SD | 16.3 ±13.5 | 16.4 ±12.7 | 1.1 ±18.3 | .97 |

Note. FPL = federal poverty level (according to the Department of Health and Human Services); SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage.

There were 3922 participants with no implausible or missing dietary, income, or education data at CARDIA examination years 0 (1985–1986), 7 (1992–1993), and 20 (2005–2006), with retention rates of 81% and 72% at years 7 and 20, respectively.

P value for analysis of variance test of difference from CARDIA years 0 and 20.

Snacks defined as corn chips, potato chips, onion rings, and unflavored and flavored popcorn.

Dessert defined as cakes, cookies, pies, pastries, Danishes, doughnuts and cobblers, frozen dairy dessert, and miscellaneous dessert.

SSBs comprise sweetened fruit drinks, sweetened water, and sweetened soft drinks.

Diet beverages comprise artificially sweetened fruit drinks, artificially sweetened soft drinks, artificially sweetened water, and unsweetened soft drinks

Population/km2.

Relative to a standard of 1 from years 1982–1984.

3-km network buffer.

Percentage of convenience stores relative to total food resources (food stores and restaurants) in a 3-km network buffer.

In unadjusted linear regression analysis, we observed statistically significant negative associations with a priori diet quality score and servings of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and ASBs, as well as positive associations with servings of processed meat, desserts, and SSBs. We found no statistically significant associations with servings of snacks.

Associations With Diet Pattern Scores

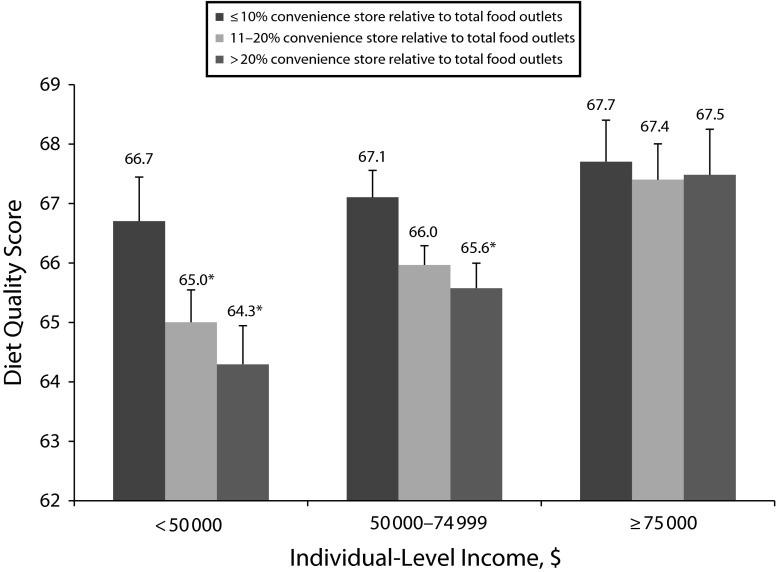

In a multivariable-adjusted analysis, the association between the a priori diet quality score and the percentage of neighborhood convenience stores differed by individual-level income (P = .001 for the interaction). For example, a higher percentage of neighborhood convenience stores relative to total food stores and restaurants was associated with lower a priori diet quality scores; this association was stronger among participants with lower (vs higher) individual-level income (10th and 90th percentiles of income; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Multivariable-adjusted model of differences in association between a priori diet quality score and percentage of convenience stores relative to total neighborhood food stores and restaurants by individual-level income, years 0–20: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study; Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; Oakland, CA; 1985–2006.

Note. Asterisk indicates that the a priori diet quality score is statistically significantly different from referent score (≤ 10% convenience stores relative to total food outlets). Adjusted for individual-level age, gender, race (Black, White), maximum educational attainment (completed elementary school, ≤ 3 years high school, 4 years high school, ≤ 3 years college, or ≥ 4 years college); community-level population density (population/km2), cost of living (relative to a standard of 1 from years 1982–1984), total food stores and restaurants (≤ 10, 11–99, ≥ 100 counts), neighborhood deprivation score (derived using principle components analysis of 4 tract-level variables: (1) percentage of tract education < high school at aged 25 years; (2) education ≥ college at aged 25 years; (3) median household income; and (4) percentage of people with household incomes < 150% of federal poverty level according to the Department of Health and Human Services), and time. All values are derived from repeated measures random effects linear regression model of percentage of convenience stores relative to total food resources (in a 3-km network buffer) on a priori diet quality score20,46 and the interaction with maximum income (continuous) reported during the study ($/y). There were 3922 participants with no implausible or missing dietary, income, or education data at CARDIA examination years 0, 7, and 20. Mean (SD) of a priori diet quality score = 66.3 (13.0).

Associations at higher individual-level income were weak or absent.

Associations With Fresh Food Groups

In multivariable-adjusted models for specific food groups, whole grain consumption was negatively associated with the percentage of neighborhood convenience stores relative to total food stores and restaurants; these associations were stronger at lower (vs higher) individual-level income (Figure A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Associations with fruit, vegetable, and processed meat consumption were not statistically significant (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Predicted Multivariable-Adjusted Model Coefficients of Longitudinal Associations Between Food Groups and Percentage of Convenience Stores, Years 0–20: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study; Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; Oakland, CA

| Servings per Week |

||||

| Food Groups (Outcome), % of Convenience Stores Relative to Total Food Stores and Restaurants (Exposure) | Mean ±SD (Range) | Estimated Associationa (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | P |

| Fruit | 1.6 ±1.7 (0.0–31.8) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 1.67 (1.60, 1.74) | 1.00 (Ref) | . . . | |

| 11–20 | 1.58 (1.53, 1.64) | −0.09 (–0.17, −0.01) | .04 | |

| > 20 | 1.63 (1.56, 1.70) | −0.04 (–0.15, 0.06) | .43 | |

| Vegetables | 2.8 ±2.4 (0.0–40.9) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 2.90 (2.80, 2.99) | 1.00 (Ref) | . . . | |

| 11–20 | 2.82 (2.75, 2.89) | −0.08 (–0.19, 0.03) | .15 | |

| > 20 | 2.81 (2.71, 2.90) | −0.09 (–0.23, 0.05) | .2 | |

| Processed meat | 0.8 ±1.0 (0.0–16.8) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 0.80 (0.76, 0.84) | 1.00 (Ref) | . . . | |

| 11–20 | 0.84 (0.81, 0.87) | 0.04 (–0.01, 0.09) | .06 | |

| > 20 | 0.82 (0.78, 0.86) | 0.02 (–0.04, 0.08) | .47 | |

| Desserts | 1.0 ±1.2 (0.0–30.7) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | . . . | |

| 11–20 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.03 (–0.03, 0.09) | .31 | |

| > 20 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | −0.01 (–0.08, 0.07) | .93 | |

| Snacks | 0.5 ±0.7 (0.0–19.4) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 0.51 (0.48, 0.54) | 1.00 (Ref) | . . . | |

| 11–20 | 0.51 (0.49, 0.53) | 0.01 (–0.04, 0.04) | .99 | |

| > 20 | 0.50 (0.47, 0.53) | −0.01 (–0.06, 0.03) | .56 | |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Adjusted for individual-level age, gender, race (Black, White), maximum educational attainment (completed elementary school, ≤ 3 y high school, 4 y high school, ≤ 3 y college, or ≥ 4 years college), maximum income ($/y) reported during the study, community-level population density (population/km2), cost of living (relative to a standard of 1 from years 1982–1984), total food stores and restaurants (≤ 10, 11–99, ≥ 100 counts), neighborhood deprivation score (derived using principle components analysis of 4 tract-level variables: (1) percentage of tract education < high school at aged 25 y, (2) education ≥ college at aged 25 y, (3) median household income, and (4) percentage of people with household incomes < 150% of federal poverty level according to the Department of Health and Human Services), and time. All values are derived from repeated measure random effects linear regression models of percentage of convenience stores among total food resources (in a 3-km network buffer) on consumption of individual food items (servings/wk). There were 3922 participants with no implausible or missing dietary, income, or education data at CARDIA examination years 0, 7, and 20.

Estimated amount is association between food group [servings/wk (continuous)] and percentage of convenience stores relative to total food stores and restaurants (≤ 10%, 11%–20%, > 20%).

Associations With Snacks and Sweetened Beverages

After adjustment for covariates, the 2-step model results showed that greater availability of neighborhood convenience stores was not statistically significantly associated with the probability of consuming SSBs and ASBs (step 1), the amount of SSBs and ASBs consumed among consumers (step 2), or the unconditional amount of SSB and ASB consumed across the full sample (Table 3).

TABLE 3—

Predicted Marginal Values and Model Coefficients of the Association Between Percentage of Convenience Stores Relative to Total Food Stores and Restaurants and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage and Artificially Sweetened Beverage Consumption, Years 0–20: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study; Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; Oakland, CA

| Food Groups (Outcome), % of Convenience Stores Relative to Total Food Stores and Restaurants (Exposure) | Predicted Probabilitya (Total Sample), (95% CI) | Predicted Amount Conditional on Consumptionb (Amount Among Consumers), (95% CI) | Predicted Unconditional Amount Consumedc (Total Sample), (95% CI)c | Predicted b for Unconditional Amount Consumedc (Total Sample), (SE) |

| SSBsd | ||||

| ≤ 10 | 0.83 (0.81, 0.84) | 1.55 (1.47, 1.64) | 1.46 (1.38, 1.54) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 11–20 | 0.84 (0.83, 0.86) | 1.57 (1.51, 1.63) | 1.48 (1.41, 1.55) | 0.04 (0.04) |

| > 20 | 0.84 (0.82, 0.86) | 1.53 (1.44, 1.61) | 1.46 (1.36, 1.56) | −0.001 (0.05) |

| ASBse | ||||

| ≤ 10 | 0.37 (0.35, 0.39) | 1.55 (1.42, 1.67) | 1.45 (1.32, 1.58) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 11–20 | 0.36 (0.34, 0.37) | 1.50 (1.41, 1.59) | 1.35 (1.25, 1.46) | −0.03 (0.03) |

| > 20 | 0.36 (0.34, 0.38) | 1.32 (1.19, 1.45) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.37) | −0.09 (0.04) |

Note. ASB = artificially sweetened beverage; CI = confidence interval. SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage. Adjusted for individual-level age, gender, race (Black, White), maximum educational attainment (completed elementary school, ≤ 3 y high school, 4 y high school, ≤ 3 y college, or ≥ 4 years college), maximum income ($/y) reported during the study; community-level population density (population/km2), cost of living (relative to a standard of 1 from years 1982–1984), total food stores and restaurants (≤ 10, 11–99, ≥ 100 counts), neighborhood deprivation score (derived using principal component analysis of 4 tract-level variables: (1) percentage of tract education < high school at age 25 y; (2) education ≥ college at age 25 y; (3) median household income; and (4) percentage of people with household incomes < 150% of federal poverty level according to the Department of Health and Human Services), and time. There were 3922 participants with no implausible or missing dietary, income, or education data at CARDIA examination years 0, 7, and 20.

Estimated marginal values are derived from repeated measure random effects logistic regression models of percentage of convenience stores among total food resources (in a 3-km network buffer) on the probability of consuming a beverage across the full sample.

Estimated marginal values are derived from repeated measure random effects linear regression models of percentage of convenience stores among total food resources (in a 3-km network buffer) on weekly servings of beverage consumption within the consumers only (conditional on consumption).

Estimated marginal values and b (SE) are derived from repeated measure random effects 2-step marginal effects models of percentage of convenience stores among total food resources (in a 3-km network buffer) on weighted means of changes in weekly servings of beverages for the full sample (unconditional of consumption).

Amount among consumers mean ±SD = 1.56 ±1.89.

Amount among consumers mean ±SD = 1.50 ±1.99.

Associations with weekly servings of snacks and desserts were also not statistically significant after adjustment for covariates. We did not observe statistically significant differences with SSB, ASB, snack, or dessert consumption by individual-level income.

Sensitivity Testing

Both the a priori diet quality score and whole grain consumption were negatively associated with the percentage of neighborhood convenience stores, and these associations were stronger in more (vs less) socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods (Table B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). Multivariable-adjusted associations with the consumption of fruit, vegetables, processed meat, snacks, and sweetened beverages were similarly not statistically significant across categories of the neighborhood-level deprivation score. Our sensitivity results yielded similar findings for the Western diet pattern score and the a priori diet score (Figure B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

In addition, we found similar patterns of findings with 1-, 5-, and 8-kilometer network buffer sizes for our analyses with a priori diet quality score by individual-level income (Table B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). The interaction term with time was not significant in any models; thus findings did not vary across examination years.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of a large, diverse cohort of young adults older than 20 years, we found that greater availability of neighborhood convenience stores was associated with lower diet quality and lower consumption of whole grains. These associations between convenience stores and diet were stronger in low (vs high) income participants. However, we found no statistically significant association between neighborhood convenience stores and consumption of fruit, vegetables, processed meat, snacks, SSBs, and ASBs, regardless of individual-level SES.

Findings from previous studies are inconsistent, with several reporting a positive association between convenience store availability and consumption of fruits, vegetables, snacks, and SSBs22,38,41–43,49 and others reporting no statistically significant association with diet behaviors.37,39,40,45,46All these studies, however, differ from our study in important ways: they used cross-sectional data, which makes it more difficult to draw inferences about causality and directionality; with 1 exception,45 they did not examine dietary patterns in addition to single food items and groups, which ignores overall diet effects; and they based availability on absolute count of convenience stores and thus did not consider alternative neighborhood eating options. Except for 2 analyses,46,49 previous studies did not examine differences by individual- or neighborhood-level SES, which may contribute to the heterogeneity of findings in the literature.

Our study shows that having a higher number of neighborhood convenience stores relative to total food stores and restaurants was inversely associated with diet quality among low-income individuals. Our findings also suggest that this relationship may be driven by decreased consumption of whole grains. In other studies, researchers report less availability of healthy foods in convenience stores, whereas availability of unhealthy foods is near universal in retail and nonretail food establishments.61

The availability of convenience stores could negatively influence the consumption of healthy food products more strongly than does consumption of energy-dense snacks and sweetened beverages because of the wide availability of the latter across multiple types of food outlets.62 In particular, we may have these findings because convenience stores typically carry less whole grains, fruit, and vegetables than do other retail food outlets (e.g., supermarkets).63

One could hypothesize that the statistically significant association between availability of convenience stores and whole grains in our study stems from the higher price of whole (vs refined) grains, as suggested in the literature.64 It is also possible that whole grains are relatively less available in convenience stores, especially in low-income neighborhoods.63,65 Alternatively, consumers at all income levels may purchase fruits and vegetables at other food outlets (e.g., grocery stores).

Our findings are consistent with research from other groups that suggest that relationships between the neighborhood environment and consumption of “healthy” foods differ by individual-level SES.39,63,66 Results of sensitivity testing also suggest that associations between the availability of neighborhood convenience stores with diet quality and consumption of whole grains differed by neighborhood-level SES. Specifically, our data suggest that greater availability of neighborhood convenience stores may promote poor diet quality in low-income participants and participants residing in more socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods.

Convenience stores in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods may offer foods of lower quality and higher cost than do stores in less deprived neighborhoods, and residents may have less access to transportation.67,68 Additionally, neighborhood crime, safety, and social ties may influence weight and diet behavior39; thus, residents may be more sensitive to the availability of low-quality foods offered at convenience stores. Therefore, potential solutions aimed at improving dietary behaviors could focus on low-income individuals and socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Previous studies have demonstrated that interventions and initiatives to increase the within-store availability and purchasing of healthy food options in convenience stores and corner stores is feasible, especially in areas with a higher density of convenience stores.29,69,70

To our knowledge, ours is the first longitudinal analysis of the association between neighborhood convenience store availability and diet behaviors. We captured changes in the food environment and diet behaviors over time in a large and diverse population-based cohort of young adults, and we examined differences in associations with diet by individual- and neighborhood-level SES. Further, we used not only measures of single food items but also 2 conceptually distinct dietary pattern scores (a priori and empirically derived) to characterize the complexity of the overall diet of participants.

Limitations

Despite these strengths, our study had several limitations. Because of the complexity of food purchasing and consumption choices within neighborhoods,71 we were unable to correct for bias owing to residential self-selection. Our measures of food consumption were derived from self-report, which is prone to recall bias and reporting error. Although street network buffers represent convenience store availability in the area surrounding participants’ residences, we were also unable to address participants’ workplaces, nor could we classify where specific food items were purchased; however, our focus on a single type of food outlet (convenience stores) takes into account the density of other food choices by conceptualizing the exposure as a proportion of convenience stores relative to total outlets, including food stores and restaurants.

Although we acknowledge that this conceptualization is 1 option among many (e.g., relative to supermarkets), we were unable to capture differences in within-store food availability or the quality of these foods; therefore, we have no way of knowing which retail food options sold healthy or unhealthy food. In addition, the Dun & Bradstreet food business record data may have contained location errors, but these errors were probably random in nature and small.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that living in neighborhoods with greater availability of convenience stores is associated with low consumption of healthy foods (e.g., whole grains) and overall poor diet quality relative to neighborhoods with fewer convenience stores. Furthermore, this association may be stronger in neighborhoods where residents are at high risk for poor diet quality and diet-related adverse cardiometabolic health outcomes and, as such, may play a role in socioeconomic disparities in diet behaviors and adverse health outcomes. Our findings suggest that efforts to increase the diversity of neighborhood food stores and restaurants or reduce the number of neighborhood convenience stores, particularly among low-income individuals, might be useful for increasing healthy diet behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ([NHLBI] grant R01HL104580); the Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ([UNC] grant R24 HD050924 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development); the Nutrition Obesity Research Center, UNC (grant P30DK56350 from the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases); and the Center for Environmental Health Sciences, UNC (grant P30ES010126 from the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences). The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study is supported by the NHLBI (contracts HHSN268201300025C, HHSN268201300026C, HHSN268201300027C, HHSN268201300028C, HHSN268201300029C, and HHSN268200900041C); the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA); and an intra-agency agreement between the NIA and the NHLBI (grant AG0005).

The authors would like to acknowledge CARDIA chief reviewer Kiyah Duffey, PhD, whose thoughtful suggestions improved the article; Marc Peterson of the UNC, Carolina Population Center (CPC); and the CPC Spatial Analysis Unit for the creation of the environmental variables.

Note. The National Institutes of Health had no role in designing or conducting the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Human Participant Protection

Written consent and study data were collected under protocols approved by institutional review boards at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Northwestern University, University of Minnesota, and Kaiser Permanente. Geographic linkage and analysis for this study were approved by the institutional review board at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

References

- 1.Hartley L, Igbinedion E, Holmes J et al. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2. CD009874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Fruits, vegetables and coronary heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(9):599–608. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffen LM, Jacobs DR, Jr, Stevens J, Shahar E, Carithers T, Folsom AR. Associations of whole-grain, refined-grain, and fruit and vegetable consumption with risks of all-cause mortality and incident coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(3):383–390. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steffen LM, Kroenke CH, Yu X et al. Associations of plant food, dairy product, and meat intakes with 15-y incidence of elevated blood pressure in young Black and White adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(6):1169–1177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1169. quiz 1363–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye EQ, Chacko SA, Chou EL, Kugizaki M, Liu S. Greater whole-grain intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and weight gain. J Nutr. 2012;142(7):1304–1313. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.155325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belin RJ, Greenland P, Allison M et al. Diet quality and the risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):49–57. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.011221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF et al. Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation. 2007;116(5):480–488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.689935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Steffen LM, Jacobs DR, Jr, Popkin BM. Drinking caloric beverages increases the risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(4):954–959. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keast DR, Nicklas TA, O’Neil CE. Snacking is associated with reduced risk of overweight and reduced abdominal obesity in adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(2):428–435. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson N, Story M. A review of snacking patterns among children and adolescents: what are the implications of snacking for weight status? Child Obes. 2013;9(2):104–115. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2477–2483. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richelsen B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and cardio-metabolic disease risks. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(4):478–484. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328361c53e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lassale C, Fezeu L, Andreeva VA et al. Association between dietary scores and 13-year weight change and obesity risk in a French prospective cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36(11):1455–1462. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duffey KJ, Steffen LM, Van Horn L, Jacobs DR, Jr, Popkin BM. Dietary patterns matter: diet beverages and cardiometabolic risks in the longitudinal Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(4):909–915. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.026682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidemann C, Schulze MB, Franco OH, van Dam RM, Mantzoros CS, Hu FB. Dietary patterns and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in a prospective cohort of women. Circulation. 2008;118(3):230–237. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.771881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutsey PL, Steffen LM, Stevens J. Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):754–761. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rumawas ME, Meigs JB, Dwyer JT, McKeown NM, Jacques PF. Mediterranean-style dietary pattern, reduced risk of metabolic syndrome traits, and incidence in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(6):1608–1614. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Income and race/ethnicity are associated with adherence to food-based dietary guidance among US adults and children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):624–635.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffensperger S, Kuczmarski MF, Hotchkiss L, Cotugna N, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. Effect of race and predictors of socioeconomic status on diet quality in the HANDLS study sample. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(10):923–930. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30711-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sijtsma FP, Meyer KA, Steffen LM et al. Longitudinal trends in diet and effects of sex, race, and education on dietary quality score change: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):580–586. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.020719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunha DB, de Souza Bda S, Pereira RA, Sichieri R. Effectiveness of a randomized school-based intervention involving families and teachers to prevent excessive weight gain among adolescents in Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057498. e57498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desroches S, Lapointe A, Ratte S, Gravel K, Legare F, Turcotte S. Interventions to enhance adherence to dietary advice for preventing and managing chronic diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008722.pub2. CD008722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR et al. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(15):1407–1416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans CE, Christian MS, Cleghorn CL, Greenwood DC, Cade JE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(4):889–901. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.030270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: a review of food deserts literature. Health Place. 2010;16(5):876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafson A, Hankins S, Jilcott S. Measures of the consumer food store environment: a systematic review of the evidence 2000–2011. J Community Health. 2012;37(4):897–911. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturm R, Cohen DA. Zoning for health? The year-old ban on new fast-food restaurants in south LA. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(6):w1088–w1097. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borradaile KE, Sherman S, Vander Veur SS et al. Snacking in children: the role of urban corner stores. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1293–1298. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebauer H, Laska MN. Convenience stores surrounding urban schools: an assessment of healthy food availability, advertising, and product placement. J Urban Health. 2011;88(4):616–622. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9576-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kersten E, Laraia B, Kelly M, Adler N, Yen IH. Small food stores and availability of nutritious foods: a comparison of database and in-store measures, Northern California, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E127. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laska MN, Borradaile KE, Tester J, Foster GD, Gittelsohn J. Healthy food availability in small urban food stores: a comparison of four US cities. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(7):1031–1035. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009992771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liese AD, Weis KE, Pluto D, Smith E, Lawson A. Food store types, availability, and cost of foods in a rural environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1916–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Nalty C. Convenience stores and the marketing of foods and beverages through product assortment. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3, suppl 2):S109–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An R, Sturm R. School and residential neighborhood food environment and diet among California youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bodor JN, Rose D, Farley TA, Swalm C, Scott SK. Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(4):413–420. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carroll-Scott A, Gilstad-Hayden K, Rosenthal L et al. Disentangling neighborhood contextual associations with child body mass index, diet, and physical activity: the role of built, socioeconomic, and social environments. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hattori A, An R, Sturm R. Neighborhood food outlets, diet, and obesity among California adults, 2007 and 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10 doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120123. E35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hearst MO, Pasch KE, Laska MN. Urban v. suburban perceptions of the neighbourhood food environment as correlates of adolescent food purchasing. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(2):299–306. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Cullen KW, Thompson D. Distance to food stores & adolescent male fruit and vegetable consumption: mediation effects. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:35. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laska MN, Hearst MO, Forsyth A, Pasch KE, Lytle L. Neighbourhood food environments: are they associated with adolescent dietary intake, food purchases and weight status? Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1757–1763. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morland K, Diez Roux AV, Wing S. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(4):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nash DM, Gilliland JA, Evers SE, Wilk P, Campbell MK. Determinants of diet quality in pregnancy: sociodemographic, pregnancy-specific, and food environment influences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(6):627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.04.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearce J, Hiscock R, Blakely T, Witten K. The contextual effects of neighbourhood access to supermarkets and convenience stores on individual fruit and vegetable consumption. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(3):198–201. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.059196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powell LM, Auld MC, Chaloupka FJ, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Associations between access to food stores and adolescent body mass index. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4, suppl):S301–S307. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shier V, An R, Sturm R. Is there a robust relationship between neighbourhood food environment and childhood obesity in the USA? Public Health. 2012;126(9):723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Izumi BT, Mentz G, Israel BA, Lockett M. Neighborhood food environment role in modifying psychosocial stress–diet relationships. Appetite. 2013;65:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Institutes of Health. Scientific resources section. Available at: http://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/exam-materials2/data-collection-forms. Accessed October 4, 2014.

- 51.Liu K, Slattery M, Jacobs D, Jr et al. A study of the reliability and comparative validity of the cardia dietary history. Ethn Dis. 1994;4(1):15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer KA, Sijtsma FP, Nettleton JA et al. Dietary patterns are associated with plasma F(2)-isoprostanes in an observational cohort study of adults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;57:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nettleton JA, Schulze MB, Jiang R, Jenny NS, Burke GL, Jacobs DR., Jr A priori-defined dietary patterns and markers of cardiovascular disease risk in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(1):185–194. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dun & Bradstreet Inc. D&B: a trusted information source for libraries and academic institutions. 2013. Available at: http://www.dnb.com/academia-library.html. Accessed January 6, 2015.

- 55.Oliver LN, Schuurman N, Hall AW. Comparing circular and network buffers to examine the influence of land use on walking for leisure and errands. Int J Health Geogr. 2007;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson AS, Boone-Heinonen J, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Are neighbourhood food resources distributed inequitably by income and race in the USA? Epidemiological findings across the urban spectrum. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000698. e000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1041–1062. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haines PSGD, Popkin BM. Modeling food consumption decisions as a two-step process. Am J Agric Econ. 1988;70(3):543–552. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Madden D. Sample selection versus two-part models revisited: the case of female smoking and drinking. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manning WG, Duan N, Rogers WH. Monte Carlo evidence on the choice between sample selection and two-part models. J Econometrics. 1987;35(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farley TA, Baker ET, Futrell L, Rice JC. The ubiquity of energy-dense snack foods: a national multicity study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):306–311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farley TA, Rice J, Bodor JN, Cohen DA, Bluthenthal RN, Rose D. Measuring the food environment: shelf space of fruits, vegetables, and snack foods in stores. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):672–682. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9390-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leone AF, Rigby S, Betterley C et al. Store type and demographic influence on the availability and price of healthful foods, Leon County, Florida, 2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(6):A140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cavanaugh E, Mallya G, Brensinger C, Tierney A, Glanz K. Nutrition environments in corner stores in Philadelphia. Prev Med. 2013;56(2):149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith ML, Sunil TS, Salazar CI, Rafique S, Ory MG. Disparities of food availability and affordability within convenience stores in Bexar County, Texas. J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:782756. doi: 10.1155/2013/782756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe CI, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM. Fast food restaurants and food stores: longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1162–1170. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blitstein JL, Snider J, Evans WD. Perceptions of the food shopping environment are associated with greater consumption of fruits and vegetables. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(6):1124–1129. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minaker LM, Raine KD, Wild TC, Nykiforuk CI, Thompson ME, Frank LD. Objective food environments and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(3):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dannefer R, Williams DA, Baronberg S, Silver L. Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e27–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song HJ, Gittelsohn J, Kim M, Suratkar S, Sharma S, Anliker J. A corner store intervention in a low-income urban community is associated with increased availability and sales of some healthy foods. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(11):2060–2067. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stark JH, Neckerman K, Lovasi GS et al. Neighbourhood food environments and body mass index among New York City adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(9):736–742. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]