Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To validate a screening instrument using self-reported assessment of frailty syndrome in older adults.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study used data from the Saúde, Bem-estar e Envelhecimento study conducted in Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil. The sample consisted of 433 older adult individuals (≥ 75 years) assessed in 2009. The self-reported instrument can be applied to older adults or their proxy respondents and consists of dichotomous questions directly related to each component of the frailty phenotype, which is considered the gold standard model: unintentional weight loss, fatigue, low physical activity, decreased physical strength, and decreased walking speed. The same classification proposed in the phenotype was utilized: not frail (no component identified); pre-frail (presence of one or two components), and frail (presence of three or more components). Because this is a screening instrument, “process of frailty” was included as a category (pre-frail and frail). Cronbach’s α was used in psychometric analysis to evaluate the reliability and validity of the criterion, the sensitivity, the specificity, as well as positive and negative predictive values. Factor analysis was used to assess the suitability of the proposed number of components.

RESULTS

Decreased walking speed and decreased physical strength showed good internal consistency (α = 0.77 and 0.72, respectively); however, low physical activity was less satisfactory (α = 0.63). The sensitivity and specificity for identifying pre-frail individuals were 89.7% and 24.3%, respectively, while those for identifying frail individuals were 63.2% and 71.6%, respectively. In addition, 89.7% of the individuals from both the evaluations were identified in the “process of frailty” category.

CONCLUSIONS

The self-reported assessment of frailty can identify the syndrome among older adults and can be used as a screening tool. Its advantages include simplicity, rapidity, low cost, and ability to be used by different professionals.

Keywords: Aged; Frail Elderly; Physical Fitness; Motor Activity; Diagnostic Self Evaluation; Questionnaires, utilization; Validation Studies

INTRODUCTION

Frailty is a clinical syndrome with a significant impact on the lives of older adults, their families, and their social environment because it is a predictor of distinct adverse health outcomes 10 and is associated with increased demand for social and health care services, significantly raising the costs of assistance. 8

Frailty is also a dynamic condition that can improve or worsen over time. Among the various definitions of frailty, two are more common: one is related to the accumulation of deficits, adding up the clinical conditions and diagnosed dysfunctions that compose the Frailty Index, 22 while the other is the frailty phenotype proposed by Fried et al. 11

Fried et al 11 characterized frailty as decreased physiological reserves and increased vulnerability of individuals, impairing their homeostatic adaptation capacity because of internal and continuous processes expressed as a phenotype composed of five measurable components: unintentional weight loss, fatigue, decreased physical strength, decreased walking speed, and low physical activity.

The frailty phenotype has been investigated in different regions of the world; its prevalence varies between 5.0% and 20.0%, and its annual incidence is 7.0%. 22 According to Fried et al, 10 the syndrome may be reversible or may be delayed if diagnosed early. 11 , 13

The measurement of four of the five components of the syndrome requires specialized equipment and training, making diagnosis in primary health care more difficult. Issues involving individuals’ self-perception about their health condition were validated in different contexts and have been widely used in assessing health, particularly as screening tools, because of their practicality, range, speed, and low cost. 1 , 2 , 16 , 20 , 21

Self-perception of frailty by the individuals themselves allows expanded screening for the syndrome and serves as an important tool in early diagnosis.

The present study aimed to validate a screening instrument for self-reported assessment of frailty syndrome among older adults.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study used a database from the Saúde, Bem-estar e Envelhecimento (SABE – Health, Welfare, and Aging) study initiated in 2000 as a multicenter survey in seven urban centers in Latin America and the Caribbean. 18 In the city of Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 2,143 older adults (cohort A00) of both sexes were selected by random sampling and interviewed in their homes. 24 In 2006, 1,115 older adults from the first cohort (cohort A06) were located and re-evaluated, and the assessment of the frailty phenotype was introduced. 10 The data were weighted to be representative of the population. The weights resulting from the sample design were added according to the strata represented (age and sex).

In 2008, on the basis of the distribution of the syndrome in the population in 2006, a subproject aimed at identifying the determining factors of frailty among longer-lived adults (≥ 75 years) was developed by monitoring every six months for two years consecutively (2008 and 2009) using telephone and home evaluations. The final sample consisted of 433 older adults who were re-interviewed in 2009, when frailty syndrome was assessed using the components proposed by Fried et al 11 (considered the gold standard) at the same time when the questionnaire used for self-assessment was implemented for validation.

The frailty phenotype 11 was obtained using the following measurable components:

Unintentional weight loss: This was calculated on the basis of the difference in weight of older adults in 2008 and 2009 measured during home evaluations. Older adults who reported a weight loss of > 3 kg in 2009 received a positive score for frailty;

Handgrip strength: This was obtained using a Takei Kiki Kogyio dynamometer (model TK 1201) and evaluated with the patient in a sitting position. Participants were asked to exert as much force as possible using their dominant arm twice in succession. Only the higher strength value was considered, and this was adjusted for the body mass index (in quartiles) and stratified by sex. For each quartile, the handgrip strength was divided into quintiles, and the cutoff value for decreased strength was considered the lowest quintile obtained (20.0% weaker);

Fatigue: Two questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) proposed by Fried et al 11 were used and subsequently validated for Brazilian older adults by Batistoni et al. 4 Participants who answered at least one question with “sometimes” or “most of the time” were included in this category and received a positive score for frailty;

Decreased walking speed: This was obtained using the walking speed test on the basis of the Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function. 14 The results were adjusted for average height and sex and stratified into quintiles. Older adults placed in the highest quintile in each stratum (20.0% slower) received a positive score for frailty;

Low physical activity: This was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) validated for the Portuguese language. 5 , 6 The total amount of energy spent on activities for a week was calculated, stratified by sex, and divided into quintiles. Older adults placed in the lowest quintile (20.0% less active) received a positive score for frailty.

The classification of frailty for both the instruments followed the proposal of Fried et al, 11 in which frail individuals were those who received positive scores for three or more components, pre-frail individuals were those who received positive scores for one or two components, and non-frail individuals were those who did not present any of the components described.

The self-reported instrument (Table 1) considered the perception of older adults or their proxy informants with respect to the components of frailty syndrome. The answers to each component were compared with the results obtained using the Fried et al model 10 to assess agreement. Subsequently, a new classification called “frailty process” was created; this included all the older adults classified as pre-frail and frail for detecting the magnitude of the syndrome in this population.

Table 1. Self-reported assessment of components of frailty syndrome among older adults. Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 2009.

| Frailty | Questions and answers |

|---|---|

| Weight loss (In this component, older adults who reported a loss of > 3 kg received a positive score) | In the last 12 months, did you lose weight without going on any diet? |

| If yes, how many kilograms did you lose? Between 1 kg and 3 kg More than 3 kg | |

| No | |

| Decreased strength | In the last 12 months, do you feel weaker or think your strength has decreased? |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| Decreased walking speed | Do you think that you are walking more slowly than you did 12 months ago? |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| Low physical activity | Do you think that you are currently performing less physical activity than you did 12 months ago? |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| Self-reported fatigue (Older adults who responded “sometimes” or “most of the time” to at least one of these questions received a positive score) | In the past week, how often did you feel that you could not perform daily activities (you started something but could not finish)? |

| Never or rarely (less than 1 day) | |

| A few times (1 - 2 days) | |

| Sometimes (3 - 4 days) | |

| Most of the time | |

| In the past week, how often did the performance of your routine activities require a major effort? | |

| Never or rarely (less than 1 day) | |

| A few times (1 - 2 days) | |

| Sometimes (3 - 4 days) | |

| Most of the time |

Cronbach’s α was used to analyze the internal consistency of the questions in the proposed instrument; values between 0.70 and 0.90 indicated good internal consistency, values < 0.70 indicated weak internal consistency, and values > 0.90 indicated very good internal consistency (possibly caused by item redundancy). 26

Factor analysis was used to verify the possibility of decreasing the number of components in the proposed instrument, provided that its accuracy (ability to identify the syndrome) was maintained. Factor analysis examined the correlations between the proposed items and verified whether the number of items could be decreased to a single dimension or variable (designated factor) to which all the variables of the series were related, thereby assuming a one-dimensional character. 19 The components of the proposed instrument and the phenotype of Fried et al 11 were submitted to principal component analysis using the Tetrachoric correlation matrix to identify the patterns of joint variation of the items and the variance individually explained by these factors. Orthogonal rotation was performed according to the varimax method 7 so that the resulting factors would be as independent as possible. Items with values > 0.32 were considered to have high factor loading and those with values ≤ 0.32 were automatically excluded from analysis.

To validate the proposed instrument, the criterion that indicated the effectiveness of the model in predicting individual performance in specific activities was used. In the present study, we used the concurrent criterion validity, which was obtained by the simultaneous application of two equivalent instruments: the phenotype model of Fried et al 11 as the gold standard (obtained with objective measurements adapted from the SABE study) and the self-reported questionnaire. Measures of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve were used to assess the ability of the proposed instrument to correctly classify subjects when compared with the gold standard method.

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Escola de Enfermagem of the Universidade de São Paulo (registered under 741/2008 dated 6/4/2008).

RESULTS

In 63.1% of the interviews, older adults were the only respondents, and in 36.9% of the cases (n = 52), the participation of proxy respondents was required either partially (auxiliary respondent) or completely (substitute respondent) because the older adults presented cognitive decline and/or functional and physical limitations that prevented them from answering the questions. We attempted to verify the equivalence between the responses of older adults and those of the proxy respondents using analysis of sensitivity and specificity between the objective and subjective assessments of frailty.

Comparison of the responses from the older adults and proxy informants indicated greater sensitivity for both pre-frailty (93.0%) and frailty (75.6%) among the proxy informants when compared with the self-reported assessments. However, the responses from the older adults showed a higher specificity (72.9%). With regard to concordance, analysis of the ROC curve indicated that both assessments (proxy and self-reported) correctly classified the evaluated subjects (61.1% and 64.6%, respectively). This was considered to be an indicator of equivalence between the results, permitting the inclusion of proxy respondents in the final sample.

The study population was predominantly women (65.4%) and individuals living with other people (79.2%). The mean age was 85.7 years (SD = 5.1), and the mean level of education was < 3 years (59.6%). With regard to health conditions, 63.5% reported the presence of two or more diseases, 65.8% reported difficulty in at least one activity of daily living, 43.3% required a caregiver, 26.1% had cognitive decline, and 18.5% experienced depressive symptoms. In the evaluation of frailty syndrome using the phenotype model of Fried et al, 11 the study group included 17.1% non-frail individuals, 45.9% pre-frail individuals, and 37.0% frail individuals, with the latter two groups accounting for 82.9% of the older adults in the frailty process (Table 2).

Table 2. Number and percentage of older adult individuals according to demographic characteristics and health conditions. Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 2009.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 150 | 34.6 |

| Female | 283 | 65.4 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 85.7 (5.1) | |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 111 | 25.6 |

| 1 to 3 years | 147 | 34.0 |

| 4 to 7 years | 151 | 34.9 |

| ≥ 8 years | 24 | 5.5 |

| Live alone | ||

| No | 343 | 79.2 |

| Yes | 90 | 20.8 |

| Proxy respondent | ||

| No | 273 | 63.1 |

| Yes | 160 | 36.9 |

| Disease | ||

| None | 68 | 15.7 |

| 1 | 90 | 20.8 |

| ≥ 2 | 275 | 63.5 |

| Depressiona | ||

| No | 353 | 81.5 |

| Yes | 80 | 18.5 |

| Cognitive declineb | ||

| No | 320 | 73.9 |

| Yes | 113 | 26.1 |

| Difficulty in one or more BADLc | ||

| No | 228 | 52.7 |

| Yes | 205 | 47.3 |

| Difficulty in one or more IADLd | ||

| No | 148 | 34.2 |

| Yes | 285 | 65.8 |

| Frailty (Model proposed by Fried et al10) | ||

| Not-fragile | 74 | 17.1 |

| Pre-fragile | 199 | 45.9 |

| Fragile | 160 | 37.0 |

| Total | 433 | 100 |

a Depression: Score > 5 points in the geriatric depression scale was considered positive.

b Cognitive decline: Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≤ 18 points.

c BADL: basic activities of daily living (eating, dressing, toileting, bathing, moving from bed to chair, and walking across a room).

d IADL: instrumental activities of daily living (taking medications, using the phone, shopping, managing own finances, and using means of transportation).

Analysis of internal consistency indicated that decreased walking speed and handgrip strength had Cronbach’s α values of 0.77 and 0.72, respectively, indicating good internal consistency. In addition, the Cronbach’s α value for low physical activity was a little less satisfactory (0.63) whereas the α values for self-reported fatigue and weight loss were unsatisfactory (0.37 and 0.31, respectively). In view of these results, we aimed to verify the possibility of decreasing the number of components in the self-reported assessment of frailty using factor analysis, provided that the patients could successfully diagnose the syndrome.

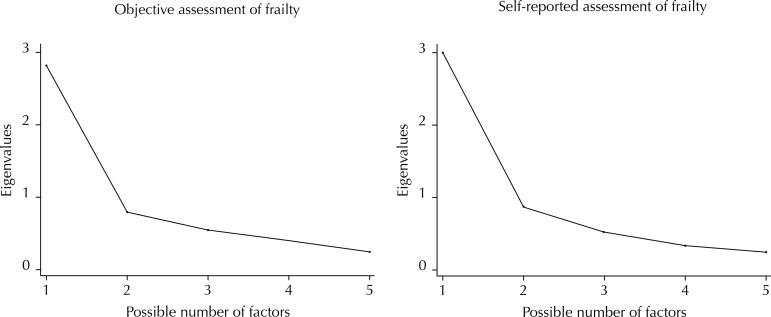

Factor analysis of the components of the model proposed by Fried et al 11 was performed to initially verify its performance and then compare this model with the proposed instrument for assessing the possibility of decreasing the number of components. This analysis indicated a regular correlation between decreased walking speed and decreased handgrip strength (r = 0.637), weight loss (r = 0.570), and reported fatigue (r = 0.424). Low physical activity showed a low correlation with weight loss (r = 0.253) and decreased handgrip strength (r = 0.329). Decreased handgrip strength showed a good correlation with weight loss (r = 0.545). Decreased walking speed was the component with the highest factor loading (FL) (FL = 0.854), i.e., its contribution to the composition of the syndrome using this evaluation was 85.4%. The components that followed were decreased handgrip strength (FL = 0.796), weight loss (FL = 0.746), fatigue (FL = 0.696), and low physical activity (FL = 0.639). Figure 1 shows the presence of a single factor with a higher eigenvalue (2.81), which distinguishes it from four other possible factors, accounting for 56.3% of the total possible variance. This indicates a correlation between components (items), suggesting that the model proposed by Fried et al 11 represented a one-dimensional framework, in which each component contributed in a particular manner to the results, each with its own specific weight and therefore unable to be excluded.

Figure 1. Eigenvalues of the objective and self-reported assessment of frailty components among older adults. Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 2009.

Subsequently, analysis was conducted using the components of the proposed instrument for assessing the maintenance of this property. Low physical activity showed a good correlation with decreased handgrip strength (r = 0.750), decreased walking speed (r = 0.668), and fatigue (r = 0.564). Decreased handgrip strength showed a good correlation with decreased walking speed (r = 0.655) and fatigue (r = 0.638), whereas weight loss showed a low correlation with the other items evaluated. Similar to the model of Fried et al, 11 the proposed instrument was composed of a single factor that included all components and accounted for 60.5% of the total variance with an eigenvalue of 3.02, which was higher than the gold standard and thereby yielded a very good explanatory power for the evaluated phenomenon.

The component that most contributed to self-reported assessment of frailty was handgrip strength, with the highest factor loading (FL = 0.892), followed by low physical activity (FL = 0.864), decreased walking speed (FL = 0.827), and fatigue (FL = 0.783). Although weight loss presented lower factor loading (FL = 0.428), its permanence in the composition of the framework was necessary.

The obtaining of the instrument containing five self-reported components was followed by concurrent validation, which indicated that low physical activity showed good sensitivity (71.2%), specificity (50.3%), and PPV (69.1%). Decreased walking speed and handgrip strength had higher sensitivity (79.0% and 77.7%, respectively), while weight loss had higher specificity (80.1%) and a good NPV (72.9%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of the precision measurements from comparing the components of objective and self-reported assessment of frailty components among older adults. Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 2009.

| Components of assessing frailty syndrome | Sensibility | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| % | % | % | % | |

| Decreased walking speed | 79.0 | 31.4 | 56.4 | 57.1 |

| Decreased handgrip strength | 77.7 | 34.9 | 44.7 | 69.8 |

| Low physical activity | 71.2 | 50.3 | 69.1 | 52.8 |

| Unintentional weight loss | 19.7 | 80.1 | 26.7 | 72.9 |

PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value

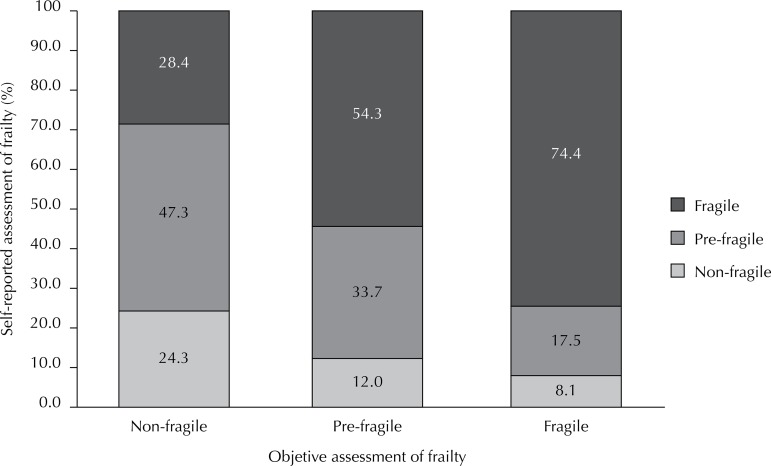

Among older adults classified as frail in the objective assessment, 74.4% were also classified as frail in the self-reported assessment. Among those classified as pre-frail in the objective assessment, 54.3% were classified as frail in the self-reported assessment. The sensitivity and specificity of the proposed instrument were 89.7% and 24.3%, respectively, among the pre-frail group, and 63.2% and 71.6%, respectively, among the frail group, indicating the perception of older adult subjects even in the early stages of the frailty process (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of the percentage of older adult individuals according to objective and self-reported assessment of frailty. Sao Paulo, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 2009.

Considering the need for early identification of individuals who are most vulnerable to frailty, we used the “frailty process” (pre-frail and frail individuals) in both the models. It was observed that 89.7% of the older adults were classified in this category in both assessments, with only 10.3% false negatives. In the precision measurements, the frailty process showed PPV of 85.2% and area under the ROC curve of 72.0%, indicating that the proposed instrument classified > 70.0% of the older adults in a correct, rapid, and simple manner.

DISCUSSION

The instrument proposed for self-reported assessment of frailty showed satisfactory levels of reliability and sensitivity. Two of the five components showed good internal consistency (handgrip strength and walking speed), one was less satisfactory (low physical activity), and the remaining two (weight loss and fatigue), despite low coefficients, were fundamental for the one-dimensional frailty framework obtained in factor analysis because these components presented high factor loading and good correlation with each other and therefore could not be removed from the instrument (Figure 1).

Although frailty syndrome involves a triad (neuroendocrine dysregulation, neuromuscular changes, and immune dysfunction), it includes a one-dimensional framework according to the phenotype model proposed by Fried et al. 11 This characteristic, essential in Fried’s model, was maintained in the proposed instrument.

The unintentional weight loss seems to be due to energy dysregulation generated by neuroendocrine and musculoskeletal disorders, malnutrition, inflammation, catabolic diseases, and decreased muscle mass. 12 , 27 Older adult individuals tend to associate weight loss without a specific cause with poor health conditions; therefore, they do not tend to admit its occurrence. Several studies have shown that weight is underestimated in both younger 3 , 15 and older populations. 20 , 21 Xue et al 27 investigated the initial manifestations and development of the frailty phenotype to assess the risk of its components and to understand its natural history and observed that weight loss was the least frequent component among older adults.

Low physical activity, decreased walking speed, and decreased handgrip strength presented higher sensitivity and PPV and were more easily diagnosed because they significantly interfered with the performance of activities of daily living. The one-dimensionality of the framework may explain the higher prevalence of these components when compared with the result obtained using the phenotype model. This becomes even more important when functional dependency is present. 9 , 10 , 25

Considering the one-dimensionality of the framework and the subjectivity of the responses, we included a variable designated “frailty process”. For a screening instrument, the identification of groups vulnerable to the syndrome is more important than accuracy. Therefore, the identification of older adults in the process of becoming frail (pre-frail and frail groups) in a given territory would allow health care strategies targeting this group to be reorganized and would also provide a more accurate assessment and diagnosis of the syndrome and possible associated factors. This would allow the establishment of targeted, efficient, and accurate treatment strategies.

Compared with the phenotype model of Fried et al, 11 the proposed instrument categorized 89.7% of the older adults with an acceptable error rate, particularly false negatives (10.3%). Older adults classified as false negatives were those considered frail using the phenotype model and non-frail in the self-reported assessment. This classification was low in comparison with another study using self-reported questions. 14 Older adults identified as false negatives responded to the interviews personally, were longer-lived, lived alone, and had better health (i.e., fewer functional limitations), better self-reported health, and fewer depressive symptoms. Considering this profile, it can be inferred that older adults themselves did not feel the progression of the syndrome because their health condition was better.

Another characteristic of the proposed instrument was the possibility of including the data provided by proxy respondents, thereby expanding the evaluation spectrum, particularly for more disabled individuals. Typically, one of the limitations of subjective information involves the use of proxy respondents, who are often used in epidemiological studies when the research subjects are unable to provide self-reported information because of functional or cognitive limitations. The decision to include proxy respondents often has the advantage of increasing the number of cases available for evaluation and achieving a more representative group of subjects with the condition of interest. 17

One limitation of the present study involves its cross-sectional design, which precluded the assessment of the predictive validity of the self-reported instrument for adverse outcomes, including functional decline, rate of hospitalization, and death.

The proposed instrument was reliable and valid for assessing frailty syndrome in primary health care and may contribute to the early identification of older adults who are more vulnerable to frailty, including those who have more difficulty in accessing health care services or who live far from care facilities, particularly in rural areas. This instrument can be extensively used, allowing health care services targeting older adults to be reorganized in each territory. Because of its easy implementation and simple and direct questions, it does not require the use of resources for the acquisition of equipment or specific training, and it can be managed by any multidisciplinary professional team in a short time and in different locations. Its large-scale use can allow the importance of frailty syndrome among older adult populations to be estimated at the national level in major and minor centers as well as in urban and rural areas.

Funding Statement

Research supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP – registered under 2009/06910-3 – through a master’s fellowship awarded to Nunes DP).

Footnotes

Research supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP – registered under 2009/06910-3 – through a master’s fellowship awarded to Nunes DP).

Based on a master’s thesis of Nunes DP, titled: “Validação da avaliação subjetiva de fragilidade em idosos no município de São Paulo: Estudo SABE (Saúde, Bem estar e Envelhecimento)”, presented to the Postgraduate Program in Public Health at the Faculdade de Saúde Pública of the Universidade de São Paulo, in 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avila-Funes JA, Gutierrez-Robledo LM, Rosales PDL. Validity of height and weight self-reported in Mexican adults: results from the national health and ageing study. 10.1590/S1517-86922008000200009J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8(5):355–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barreto PS, Greig C, Ferrandez AM. Detecting and categorizing frailty status in older adults using a self-report screening instrument. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.08.003Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(3):2. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basterra-Gortari JB, Bes-Rastrollo M, Forga LI, Martínez JA, Martínez-González MA. Validación del índice de masa corporal auto-referido en la Encuesta Nacional de Salud. 10.4321/S1137-66272007000500006An Sist Sanit Navar. 2007;30(3):373–381. doi: 10.4321/s1137-66272007000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batistoni SST, Neri AL, Cupertino APFB. Validade da escala de depressão do Center for Epidemiological Studies entre idosos brasileiros. 10.1590/S0034-89102007000400014Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(4):598–605. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedetti TRB, Mazo GZ, Barros MV. Aplicação do Questionário Internacional de Atividade Física para avaliação do nível de atividades físicas de mulheres idosas: validade concorrente e reprodutibilidade teste/reteste. Rev Bras Cienc Mov. 2004;12(1):25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedetti TRB, Antunes PC, Rodriguez-Añez CR, Mazo GZ, Petroski EL. Reprodutibilidade e validade do Questionário Internacional de Atividade Física (IPAQ) em homens idosos. 10.1590/S1517-86922007000100004Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2007;13(1):11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comrey AL, Lee HB. Interpretation and application of factor analytic results. In: A first course in factor analysis. 2. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fassbender K, Fainsinger RL, Carson M, Finegan BA. Cost trajectories at the end of life: the Canadian experience. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.007J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, Fried LP, Cutler GB, Jr, Walston JD. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.xJ Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(4):625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleg JL, Morrell CH, Bos AG, Brant LJ, Talbot LA, Wright JG, et al. Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545459Circulation. 2005;112(5):674–682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J., et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried LP, Walston JM. Frailty and failure to thrive. In: Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 5. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. 1487 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:418–423. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. M85-9410.1093/geronj/49.2.M85J Gerontol. 1994;49(2) doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert R, Bravo G, Korner-Bitensky N, Voyer L. Predictive validity of a postal questionnaire for screening community-dwelling elderly individuals at risk of functional decline. 10.1093/ageing/25.2.159Age Ageing. 1996;25(2):159–167. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAdams MA, Van Dam RM, Hu FB. Comparison of self-reported and measured BMI as correlates of disease markers in U.S.adults. 10.1038/oby.2007.504Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(1):188–196. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson LM. Proxy respondents in epidemiologic research. Epidemiol Rev. 1990;12:71–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palloni A, Peláez M. Histórico e natureza do estudo. In: O projeto SABE no Brasil: uma abordagem inicial. Brasília (DF): Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde; 2003. pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasquali L. Psicometria: teoria dos testes na psicologia e na educação. Petrópolis: Vozes; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peixoto MRG, Benício MHDA, Jardim PCBV. Validade do peso e da altura auto-referidos: o estudo de Goiânia. 10.1590/S0034-89102006000700015Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40(6):1065–1072. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000700015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rech CR, Petroski EL, Böing O, Babel RJ, Jr, Soares MR. Concordância entre as medidas de peso e estatura mensuradas e autorreferidas para o diagnóstico do estado nutricional de idosos residentes no sul do Brasil. 10.1590/S1517-86922008000200009Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2008;14(2):126–131. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockwood K, Mitnitski AB, MacKnight C. Some mathematical models of frailty and their clinical implications. 10.1017/S0959259802012236Rev Clin Gerontol. 2002;12(2):109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos-Eggimann B, Cuenoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of frailty in middle aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. 10.1093/gerona/glp012J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(6):675–681. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva NN. Processo de amostragem. In: O projeto SABE no Brasil: uma abordagem inicial. Brasília (DF): Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde; 2003. pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snih SA, Markides KS, Ottenbacher KJ, Raji MA. Hand grip strength and incident ADL disability in elderly Mexicans Americans over a seven-year period. 10.1007/BF03327406Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(6):481–486. doi: 10.1007/BF03327406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue QLL, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R, Zhou J, Fried LP. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. 10.1093/gerona/63.9.984J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63A(9):984–990. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]