Abstract

Skin appendage formation represents a process of regulated new growth. Bromodeoxyuridine labeling of developing chicken skin demonstrated the presence of localized growth zones, which first promote appendage formation and then move within each appendage to produce specific shapes. Initially, cells proliferate all over the presumptive skin. During the placode stage they are organized to form periodic rings. At the short feather bud stage, the localized growth zones shifted to the posterior and then the distal bud. During the long bud stage, the localized growth zones descended through the flank region toward the feather collar (equivalent to the hair matrix). During feather branch formation, the localized growth zones were positioned periodically in the basilar layer to enhance branching of barb ridges. Wnts were expressed in a dynamic fashion during feather morphogenesis that coincided with the shifting localized growth zones positions. The expression pattern of Wnt 6 was examined and compared with other members of theWnt pathway. Early in feather development Wnt 6 expression overlapped with the location of the localized growth zones. Its function was tested through misexpression studies. Ectopic Wnt 6 expression produced abnormal localized outgrowths from the skin appendages at either the base, the shaft, or the tip of the developing feathers. Later in feather fi-lament morphogenesis, several Wnt markers were expressed in regions undergoing rearrangements and differentiation of barb ridge keratinocytes. These data suggest that skin appendages are built to specific shapes by adding new cells from well-positioned and controlled localized growth zones and that Wnt activity is involved in regulating such localized growth zone activity.

Keywords: feather, proliferation, transduction

Feather formation, a topologic transformation from a flat epithelium to a complex three-dimensional branched skin appendage, begins with reciprocal interactions between the epithelium and the underlying mesenchyme (Saunders, 1948; Dhouailly, 1984; Chuong, 1993; 1998; Chuong et al, 2000a). Neither the epithelium nor the mesenchyme is individually potent to form appendages (Dhouailly, 1975; Sengel, 1976; Jiang et al, 1999). The initial signal specifying the location, size, and structural identity of an appendage arises from the mesenchyme and the responding epithelium forms the appropriate appendage and determines its orientation (Novel, 1973; Chuong et al, 1996). Early feather bud primordia through the short bud stage are radially symmetric. Around the late short bud stage the feathers are transformed to bilaterally symmetric structures with the molecular determinants distributed across the anterior–posterior (AP) axis. Shortly thereafter, the proximal–distal axis forms leading to an elongation phase of growth where new cells are added to the distal and flanking regions. Balanced interactions between the anterior and posterior compartments play a major part in the formation of the posterior–distal axis (Widelitz et al, 1999). In the late long bud stage, the epithelium invaginates into the dermis to form the feather follicle. The growth and structure of feathers during their initial formation and subsequent feather cycles is thought to be due to the presence of a localized growth zone (LoGZ) that contains cells with a higher mitotic potential than the rest of the bud (Chuong et al, 2000a; Widelitz and Chuong, in press). Scales are also chicken epidermal integument derivatives, but do not contain a LoGZ and remain flat (Chuong et al, 2000a,b).

To begin to understand these different phases of feather growth, we sought to characterize the LoGZ and to examine the molecular determinants that regulate its size and placement within developing feathers. The signaling of secreted, soluble factors through membrane bound receptors has been implicated in the morphogenesis of a number of vertebrate systems. The Wnt family falls into this class of molecules and signals through the frizzled receptors. In humans there are 19 Wnts and 10 frizzled receptors (Malbon et al, 2001). As they have not been purified as yet, it is unknown which frizzled receptors mediate the functions of each of the Wnts. The Wnts have been implicated in regulating growth control and development in a number of experimental systems. Here, we focus on skin appendages. In the hair, Wnt 3a and 10b are expressed in the hair matrix (St Jacques et al, 1998). Ectopic expression of Wnt 3a produces shortened hairs (Millar et al, 1999). Wnt 4 may play a part in epidermal–mesenchymal interactions (Saitoh et al, 1998). Wnt 5a is regulated by sonic hedgehog during dermal condensation formation (Reddy et al, 2001). β-catenin expression was found to cause hair tumors (Gat et al, 1998). Recently, blockage of Wnt activity via overexpression of Dickkopf 1 was shown to block hair initiation (Andl et al, 2002). In feathers, Wnt 7a was found to regulate the polarity of development (Widelitz et al, 1999), whereas ectopic β-catenin expression led to ectopic feather formation and the conversion of scales to feathers (Noramly et al, 1999; Widelitz et al, 2000). To explore further the LoGZ and its regulation, we have extended our investigation to examine the expression domains of Wnt 6 during feather formation.We have also compared Wnt 6 withWnt 5a, 8c, 11, and 14 and characterized the expression of some frizzled receptors and their soluble competitor sfrp 2. Furthermore, we have misexpressed Wnt 6 to examine its function in feather growth.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

Antibodies against bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) were from Sigma (St Louis, MO), against proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were from Chemicon (Temecula, CA), and against retroviral GAG were from Spafas Charles River Laboratories (North Franklin, CT). Each was used following the manufacturer's recommended protocols.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

This procedure was carried out according to procedures described in Nieto et al (1996). Embryos or skins were dissected in RNase free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight. Samples were dehydrated and rehydrated through a series of increasing and decreasing concentrations of methanol, respectively. They were bleached with hydrogen peroxide and digested with proteinase K and then fixed again in 0.2% gluteraldehyde in 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were treated with prehybridization buffer at 65–70°C before hybridizing them in hybridization buffer containing 2 μg per ml digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes at 65–70°C overnight. Posthybridization washes were carried out the following day in 2 × sodium citrate/chloride buffer containing 0.1% Chaps three times, 0.2 × sodium citrate/chloride buffer containing 0.1% Chaps thrice and twice in phosphered buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20. They were then blocked in 20% goat serum in phosphered buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 before incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche Indianapolis, IN) at 4°C overnight. Samples were washed with phosphered buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 containing 1 mm levamisole for 1h each for at least five times. For the color reaction, the samples were first equilibrated in 100 mm Nacl, 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 9.5, 50 mm MgC12, 0.1% Tween-20 (NTMT) solution containing 100 mm Tris–HCl, pH 9.5, 50 mm MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20. Alkaline phosphate substrates 4-nitroblue tetrazollum chloride (NBT) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl phosphate (BCIP) were added 4.5 μl and 3.5 μl per ml of 100 mm Nacl, 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 9.5, 50 mm MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20 (NTMT) respectively.

Paraffin section in situ hybridization

This procedure was carried out according to procedures described in Nieto et al (1996). Briefly, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated through a series of ethanol, and embedded in Paraffin wax. Sections were cut at 7–10 μm thickness and then mounted on positively charged coated slides. The sections were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through an ethanol series prior to the start of the experiment. The specimens were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde after digested with 10 μg proteinase K per ml for 5 min. The tissue sections were then hybridized overnight at 60°C in the hybridization buffer containing 1 ng per ml of digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes. Posthybridization washes were carried out using 100 mm Nacl, 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 9.5, 50 mm MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20 and 2 × sodium citrate/chloride buffer. Digestion with RNase A (10 μg per ml) was followed by blocking of slides in blocking solution. The samples were then incubated with alkaline phosphatase conjugated sheep anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche). The bound antibody was detected using an alkaline phosphatase substrate, BM Purple.

BrdU labeling

Eggs were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C and collected in a Petri dish containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium without serum according to Hamburger and Hamilton (1951). Dorsal skins were dissected from embryos, stage 28–34 with the help of watchmaker's forceps. In multiwell plates, the tissues were pulsed with 20 m m BrdU diluted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air for 30–90 min.This was followed by fixing the tissue in 100% methanol and bleaching with 10% hydrogen peroxide in 1 : 4 dimethyl sulfoxide/100% methanol, rehydrating in PBS and denaturing them with 2 m HCl and neutralizing the acid by immersing the tissues in 0.1 m sodium borate (pH 8.5). The tissues were incubated with anti-BrdU antibody diluted 1 : 100 in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. The secondary and tertiary antibodies used were biotinylated anti-mouse IgG diluted 1 : 300 and streptavidin horseradish peroxidase diluted 1 : 400 in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, respectively. The tissues were washed with PBS before each antibody was applied. Peroxidase was detected using the 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate.

Retrovirus preparation and transduction

Replication competent avian sarcoma virus (RCAS) directing the constitutive expression of Wnt 6 was prepared following the method of Morgan and Fekete (1996). Briefly, chicken embryo fibroblasts were transfected by lipofection with lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were maintained in the logarithmic phase of growth in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Once the culture reached approximately 70% confluence, the media was replenished and the medium containing virus was collected at 24 h. Viral titers were determined by staining for the viral GAG product and by assessing the expression of the exogenous gene. The virus was introduced to the amniotic fluid of E2–E3 chicken embryos to allow transduction of the skin. Transduction at this time produced more obvious phenotypes in the growth of the feather follicles.

RESULTS

Shifting position of the LoGZ in feather development

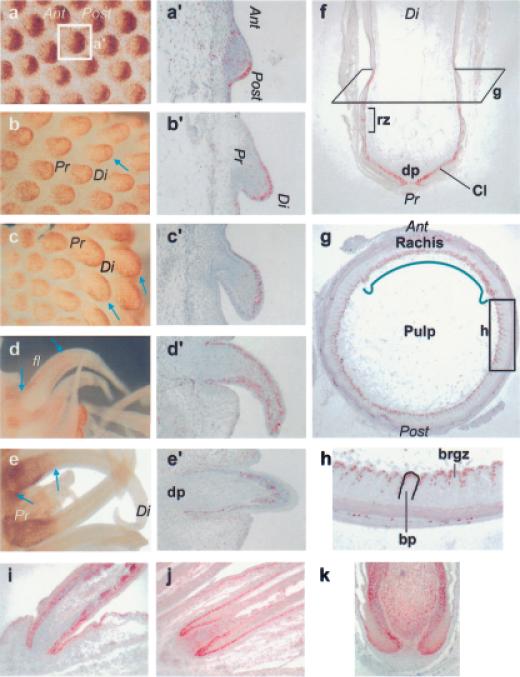

Short-term BrdU labeling was used to demonstrate the localization of growth zones in developing feathers. The LoGZ is defined as high BrdU labeling in a localized area of developing organ primordia. Placodes form in the absence of cell proliferation (Wessels, 1965). At the placode stage, the feather primordia have radial symmetry. At the early short bud stage most of the proliferating cells localized to the posterior epithelial compartment (Fig 1a,a’), which led to the development of AP asymmetry. At the molecular level, these two compartments are strikingly different and activate different sets of genes. After establishing the AP orientation, the proximal–distal axis was established. At the late short bud stage, the LoGZ was present in the distal epithelial zone (Fig 1b,b’, arrow). During the early long bud phase, proliferation continued to be located in the distal epithelium (Fig 1c,c’, arrows). The proliferation zone gradually shifted down the feather from the distal zone of the bud during the long bud stage to the flank region (Fig 1d’). At this transition stage, nonproliferative areas surrounded the LoGZ, proximally and distally (Fig 1d, arrows indicate the LoGZ). Later, in the follicle stage, a layer of cells invaginated into the dermis and initiated the formation of the feather follicle. At this stage growth occurred at the feather base (Fig 1e, see arrows; Fig 1e’ was cut at an oblique angle to show just the base of the follicle). In a later staged follicle, proliferation remained at the proximal end of the feather, called the collar (equivalent to the hair matrix; Fig 1). Above this proliferative collar is the ramogenic zone, which is the region where the feather filament epithelial cylinder starts to form barb ridges and rachidial ridges. Whereas the majority of proliferation takes place at the base of the feather filament some proliferation was observed further up the feather filament. A cross-section of the feather filament in the early barb ridge (indicated as the plane in Fig 1f) shows that proliferation also was localized to the germinative basal epithelial layer of the forming barbs, or the barb ridge growth zone (Fig 1g). A higher magnification view shows that these basal layer cells were invaginating to produce the feather barbs (Fig 1h).

Figure1. Localized proliferation centers (LoGZ) shift during feather morphogenesis.

Skin explants were pulse labeled with BrdU (20 μm) for 30–90 min to label proliferating cells. The skins were fixed and stained with anti-BrdU antibodies. Antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase staining using the 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate. The highlighted short bud shown in wholemount (a) is also shown after long-itudinal section (a’). Wholemount (a–e) and corresponding section (a’–e’) immunostaining are shown at different short bud (a,a’,b,b’), long bud (c,c’,d,d’), and follicle (e,e’) stages. Longitudinal (f) and cross (g,h) sections of an adult feather follicle are used to show filament branching and the ramogenic zone of barb ridges. The rachis in the anterior region of the follicle does not branch. Proliferation (blue arrows in b–d) can be seen in the posterior early short feather bud, distal late short bud, along the flank of the long bud and at the base of the feather follicle. PCNA staining (i–k) in the long bud (i, equivalent to d), in the forming follicle (j) and in the developed follicle (k) showed additional mesenchymal proliferation zones. Ant (anterior), Post (posterior), Pr (proximal), Di (distal), fl (flank), dp (dermal papilla), Cl (collar), bp (barb plate), rz (ramogenic zone).

BrdU incorporation showed more staining in the epidermis. At different developmental stages through development, proliferation in both the epithelium and mesenchyme shift positions. For example, BrdU labeled the posterior feather mesenchyme clearly, whereas the short buds grew to become the long buds (Chen et al, 1997). Here we also used PCNA staining to show more clearly proliferation within the mesenchyme (Fig 1i–k). This is particularly clear in early and late follicle stages (Fig 1j,k), but less so in the long feather buds (Fig 1i).

Wnt expression pattern

We initially surveyed the expression of patterns of several Wnt pathway members at the short feather buds stage, the long feather bud stage, and in the feather follicle stage.

The short bud stage

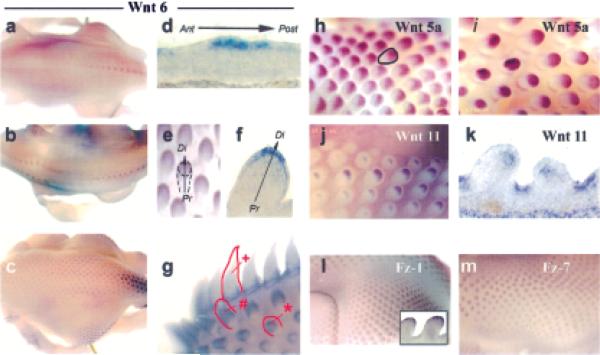

The localization of Wnt 6 was examined in growing feathers using whole-mount and section in situ hybridization and its distribution was compared withWnt 5a, 8c, 11, 14, Fz 1, and Fz 7. At E8–E9, Wnt 6 exhibited partially overlapping patterns with Wnt 5a, and cFz-1 in the LoGZ. Wnt 6 expression initiated along the caudal midline and concentrated in the forming feather buds while diminishing in the interbud domains (Fig 2a). Expression then bifurcated at the spinal tract (Fig 2b).

Figure 2. In situ hybridization showing Wnt and Fz expression during the short feather bud stage.

Wnt 6 wholemount in situ hybridization at E6.5 (a), E7 (b), and E8 (c). The short feather bud is shown in e and f. Wholemount staining (g) shows the shift of Wnt 6 staining in feather buds at several different stages of development (*, short bud; #, long bud; +, follicle) with feathers at each stage outlined. Wnt 6 section in situ hybridization at the placode (d) and short bud (f).Wholemount in situ hybridization expression patterns of Wnt 5a (h,i), Wnt 11 (j), Fz-1 (l), and Fz-7 (m) were also determined. Section in situ hybridization showed the distribution of Wnt 11 at the short bud stage (k). Feathers are outlined in panels a, d, and e.Wnt 5a, 6, Fz-1, and Fz-7 each were expressed in the posterior epithelium of the early short bud and the distal epithelium of the late short bud showing coexpression with the LoGZ. Wnt 11 was in the interbud epithelium and distal mesenchyme. Ant (anterior), Post (posterior), Pr (proximal), Di (distal).

Later, as feathers developed bilaterally from the midline, Wnt 6 was newly expressed in the forming feather buds and continued to be expressed in the growing buds near the midline (Fig 2c). Wnt 6 was strongly expressed in the posterior compartment of the developing bud (Fig 2d). With further progression and growth, Wnt 6 expression shifted to the distal compartment epithelium (Fig 2e,f). The dermal components and the interbud areas were negative. As the Wnts are secreted molecules, however, they may influence the adjacent mesenchyme. Wholemount section in situ hybridization shows Wnt 6 staining toward the tip of short buds (*), in the flank of early long feather buds (#) and toward the base of feather follicles (+) (Fig 2g).

Wnt 5a also was expressed in the posterior compartment during the early short bud stage (Fig 2h). As the bud lengthened and the posterior domain extended along the AP axis, its expression moved to the distal zone at the late short bud stage (Fig 2i). A ring of cells expressingWnt 5a appeared at the base of the feathers at this stage. Wnt 8c and Wnt 14 were all over the short bud epithelium (data not shown). Wnt 11 was initially expressed in the interbud area and was absent from the feather buds. At the late short bud stage its expression was seen in the distal mesenchyme and also in the interbud epithelium (Fig 2j,k). Consistent with the presence of the LoGZ, Fz-1 and Fz-7 expression were seen in the posterior epithelium at the early short bud stage (Fig 2l,m) and later in the distal epithelium (Fig 2l, inset).

The long bud stage

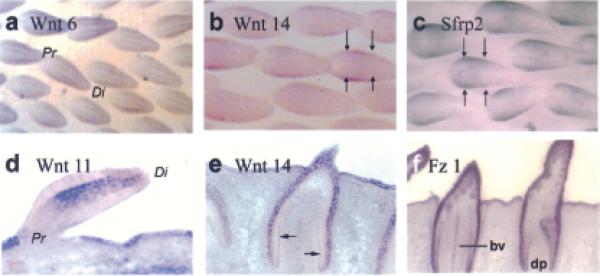

The long bud stage is characterized by the acquisition of the proximal–distal axis and manifested by height < base. BrdU incorporation and PCNA staining at this stage were seen to progressively shift down the feather filament to the lower section of the bud (Fig 1c,d,i,j). Whereas several Wnts were expressed in the vicinity of the LoGZ at this time, Wnt 6 was expressed in regions undergoing differentiation. It was expressed in stripes along the proximal–distal axis of the bud marking the barb (Fig 3a).Wnt 14 and sfrp 2 were expressed within the BrdU and PCNA defined zone (Fig 3b,c, between the arrows). They were both initially expressed all over the bud epithelium at the short bud stage (not shown) and later were restricted to the proliferation zone in the long bud. At the late long bud stage, invagination of the follicle has begun. Wnt 14 was strongly expressed in the epithelium (Fig 3e). Its expression was marked in the developing germinative layer of the early follicle (see arrows). Fz-1 was expressed more extensively all over the epithelium at this stage (Fig 3f). It was also seen in the ramogenic zone, highlighting the invaginated basal layer of proliferating cells and the central blood vessel. Wnt 11 was expressed in the distal feather mesenchyme and the interbud epithelium at this stage (Fig 3d).

Figure 3. In situ hybridization showing distribution of Wnt and Fz during the long feather bud stage.

The distribution of Wnt 6 (a),Wnt 14 (b,e), Sfrp 2 (c),Wnt 11 (d), and Fz 1 (f). Note Wnt 6 in the barb ridges, Wnt 14 and Sfrp 2 in the flank region when LoGZ is descending. Later in the forming follicle, Wnt 14, Fz 1 and other Wnt members are in the collar region. Pr (proximal), Di (distal), bv (blood vessel), dp (dermal papilla).

The feather follicle

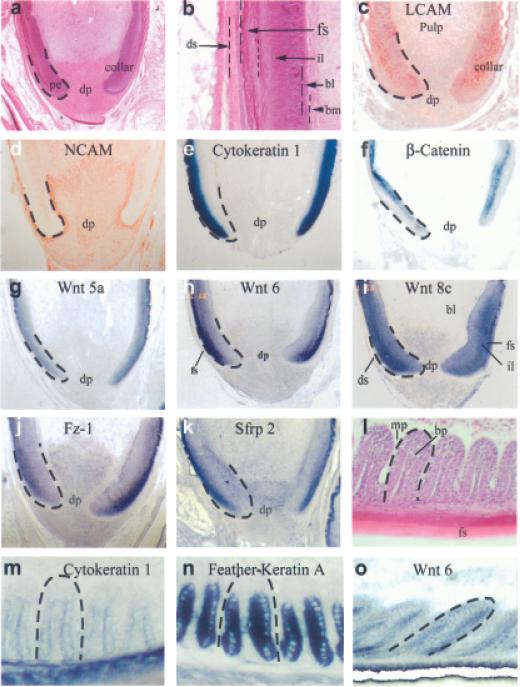

In the adult chicken, each feather is rooted in the dermal region with a follicular structure, which is fixed to the dermis by a dense network of connective tissues and muscles. At the base of the follicle, the dermal papilla interacts with the papillary ectoderm and generates new epithelial cells (Fig 4a). Above the dermal papilla is the collar epithelium that is equivalent to the hair matrix and contains the transit amplifying cells. The follicle epithelium is stratified into the basal layer, intermediate layer, and follicle sheath (Fig 4b). PCNA and short-term BrdU labeling localized to the basal layer of the follicle epithelium containing cells of unlimited replicative potential (Fig 1f) and to the pulp and dermal papilla (Fig 1k). Liver cell adhesion molecule was expressed throughout the follicle epithelium (Fig 4c). Neural cell adhesion molecule was expressed in the mesenchyme, including the dermal papilla and dermal sheath (Fig 4d). Cytokeratin 1 (Presland et al, 1989), a feather keratin differentiation marker, was expressed throughout the intermediate layer of cells (Fig 4e).

Figure 4. Co-expression of differentiation markers with Wnt and Fz during the follicle stages.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining reveals the structure of the feather follicle (a,b,j). The dermal papilla (dp) is at the base of the follicle. The collar region is above this. The papillary ectoderm (pe) descends on either side of the follicle (a). A higher power view shows the feather layers (b). The outer region is the dermal sheath (ds). The next layer is the follicle sheath (fs), then the intermediate layer (il) and basal layer (bl). A basement membrane (bm) separates the epithelium from the mesenchyme. Immunostaining shows the distribution of L-CAM (c) and neural cell adhesion molecule (e) in the developing follicle. in situ hybridization shows the distribution of β-catenin (f), Wnt 5a (g), Wnt 6 (h), Wnt 8c (i), Fz-1 (j), and Sfrp 2 (k) in the feather follicle. Barbs form at the beginning of feather branching (l). The marginal plate (mp) cells will eventually die to leave space between adjacent barbule plate (bp) epithelia. We used in situ hybridization of cytokeratin 1 (m), and feather keratin A (n) as markers. Wnt 6 (o) is in the barb ridges of the ramogenic zone.

The Wnt 6 expression profile was generated to see how its distribution correlated with the different feather domains. The distribution then was compared with that of β-catenin and other Wnt family members. Wnt 6 (Fig 4 h) expression was weak in the basal layer and strong in the intermediate layer of the follicle and overlapped with the distribution of Wnt 5a (Fig 4 g), Wnt 14 (not shown), Fz 1 (Fig 4j), and Sfrp 2 (Fig 4k). β-catenin was expressed exclusively in the proliferative basal epithelial layer (Fig 4f). β-catenin was shown to be in the feather germs (Noramly et al, 1999; Widelitz et al, 2000). Previous work focused more on the protein subcellular localization and considered that β-catenin mRNA should be ubiquitous. This was shown not to be the case. We were one of the first to show the remarkable β-catenin mRNA expression from a homogeneous expression pattern to a restricted circular pattern in the developing feather germ with a negative halo surrounding it (Jiang et al, 1999; Widelitz et al, 2000). Subsequently, a similar mRNA expression pattern was found in developing hair germs (Huelsken et al, 2001). Wnt 8c was strongly expressed throughout the follicle epithelium, including the follicle sheath, intermediate, and basal layers (Fig 4i).

Branching morphogenesis occurs above the collar region in the ramogenic zone. The epithelial sheet invaginates periodically to segregate regions that will either apoptose or keratinize (Chuong et al, 2000a) (Figs 1f and 4 l). Proliferating cells were localized to the basal layer of the forming barbs ridges (Fig 1g,h). The intermediate layer contains cells that undergo differentiation to form the intricate branch pattern of the feather. Cytokeratin 1 expression was weakly expressed in the barbule plate cells of the differentiating ramogenic zone (Fig 4 m), but feather keratin A was strongly expressed in the barbule plate cells (Fig 4n). Wnt 6 was also expressed in the barbule plate of the barb ridge (Fig 4o) and may contribute to differentiation at this time, although it may also be involved in maintaining the few proliferating cells retained in this layer.

Alteration of feather morphology by misexpression of Wnt 6

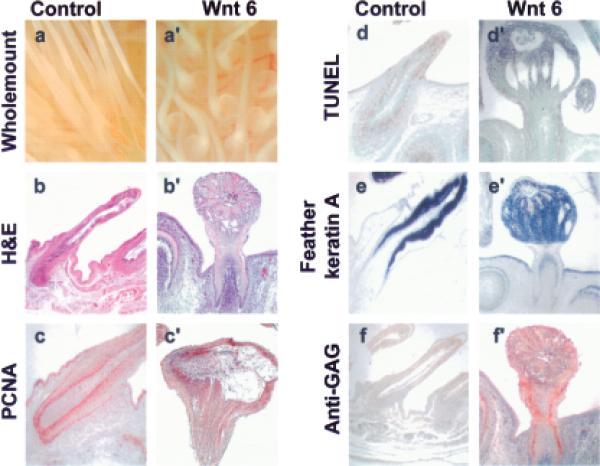

The expression pattern of Wnt 6 and several other Wnt members closely coincided with the pattern of the LoGZ. We tested the possible involvement of Wnt 6 in regulating growth by ectopically expressing it from a RCAS. RCAS–Wnt 6 was microinjected into the amniotic space surrounding E3 embryos. Phenotypic changes were examined at E15 (n > 50 feather buds, in at least three independent embryos). Normal and RCAS control feather buds were long and slender (Fig 5a); however, ectopic Wnt 6 expression produced feather buds with enlarged regions at either the base, along the shaft or at the tip (Fig 5a’ shows enlarged feathers at the base). The enlarged area, clearly seen in hematoxylin and eosin stained longitudinal sections in comparison with controls contained many dyskeratotic cells (Fig 5b,b’). Staining with PCNA to detect proliferating cells shows that the proliferating regions were expanded in the Wnt 6-transduced feathers compared with controls (Fig 5c,c’). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end-labeling staining showed that apoptosis overlapped with regions of proliferation and occurred at similar levels in the control and expanded Wnt 6 transduced feather epithelium (Fig 5d,d’). Hence the enlargement is due to proliferation rather than diminished cell death. Although enlarged in size, these buds differentiated to express feather keratins (Fig 5e,e’). Immunostaining for the presence of retrovirus with an anti-GAG antibody showed that the cultures were transduced in the mesenchyme of the invaginating follicle and in the epithelium of the growing shaft (Fig 5f,f’).

Figure 5. Misexpression of Wnt 6 results in localized enlarged regions of transduced feathers.

Chicken embryos were transduced with the RCAS retrovirus directing expression of control vector (a–f) or Wnt 6 (a’–f’) and the phenotypes were viewed in wholemount (a,a’) or section (b–f’). Normal feather buds are long and slender. Transduction with RCAS–Wnt 6 produced a localized enlarged region, which may be localized at the tip, the shaft, or the base of the feather filament. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (b,b’), PCNA (c,c’), terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end-labeling (d,d’), anti-feather keratin antibodies (e,e’) or anti-p27 antibody to detect the presence of the RCAS virus (f,f’). Note the enriched viral transduction region in the enlarged area. Proliferation was also active, but the cells could differentiate to express feather keratin. There was not much difference in terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end-labeling staining.

DISCUSSION

The LoGZ is a morphogenesis organizer in developing skin appendages

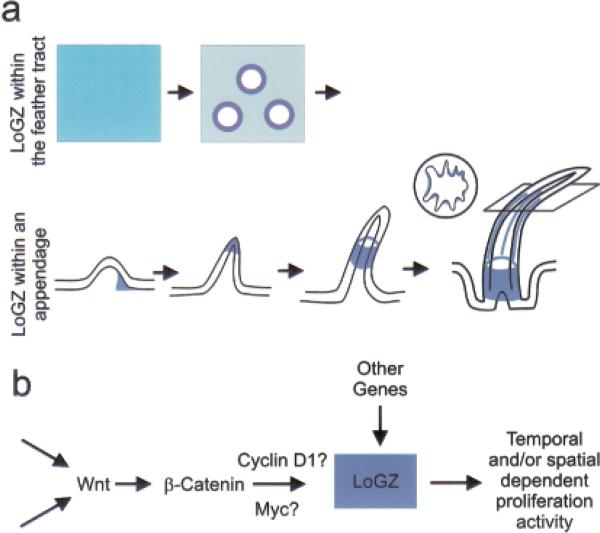

Juxtaposed cell proliferation and death zones that are distributed in a spatiotemporal-specific manner craft the shape of many organs. For example, during limb development, the apical ectodermal ridge at the distal tip is a signaling center, which promotes a LoGZ in the underlying progress zone, mainly through the activity of fibroblast growth factor pathway members. BMP-4 induced Dkk-1 inhibits Wnt signaling, which leads to apoptosis in specific regions during normal limb development (Grotewold and Ruther, 2002). The disappearance of the apical ectodermal ridge and progress zone mark the end of limb bud elongation and the loss of regeneration capacity (Saunders, 1948; Fallon et al, 1994; Laufer et al, 1994; Niswander et al, 1994; Mahmood et al, 1995). Skin appendages, on the other hand, continue to proliferate and cycle through the life of an organism. During hair development, proliferation is first seen in the hair germ region and becomes localized to the proximal matrix cells that drive continuous proximal–distal outgrowth (Hardy, 1992) and allow cycling and regeneration to occur. Without these molding and sculpting forces, new growths will become ball-like in shape, like many tumors. Whereas a specific organizer has not been identified in feathers, in this study we describe the behavior of the LoGZ; regions in developing organ primordia with enhanced proliferation activity.We then analyzed their possible roles in regulating organ size and shape. In feathers, the growth zone is first in the posterior region, then the distal tip of the bud, and later shifts to the base of the follicle, which allows for continued feather growth and cycling. This demonstrates that proliferation zones are localized but can shift positions during feather morphogenesis (Fig 6a). The position of the LoGZ suggests that it helps to establish the AP and proximal–distal axes in developing feather buds and increase feather length. The high mitotic activity of the LoGZ can be either an inherent property of a group of cells or a response to specific molecular signals. The Wnt expression patterns described in this study suggest they play a part in LoGZ regulation.

Figure 6. Schematic diagram showing the shifting LoGZ during feather morphogenesis and the involvement of the Wnt pathway.

The skin forms with equal proliferation abilities throughout. Proliferation then is suspended for about 18 h as mesenchymal cells migrate and adhere to form high-density dermal condensations (Wessels, 1965). This organizes the skin into distinct bud and interbud zones. Through the action of positive and negative regulators, growth is potentiated within the newly formed buds, but continues to be suppressed in the interbud zone (Noveen et al, 1995). These are shown schematically from a top view on the top row. As the short feather buds form, proliferation becomes localized to centers, in the posterior bud (Chen et al, 1997). As the feathers grow, the LoGZ moves to the distal region in the late short bud. It then shifts through the feather flank to the base of the feather follicle during the long bud stage. In the ramogenic zone, proliferation is seen continuously in the rachidial ridge and periodically in the barb ridges. These are shown in schematic form from a side view (a). (b) A working model depicting the tentative molecular basis of LoGZ activities. It shows the potential relationship between the Wnt–β-catenin pathway and known cell proliferation related genes.

In contrast, scales do not have a LoGZ and therefore remain flat (Tanaka and Kato, 1983). Many molecules expressed during feather development are indeed also expressed during avian foot scale development but are expressed to lower levels with a more diffuse distribution. β-catenin levels are high in feather tract regions and low in scale tract regions (Widelitz et al, 2000). Induction of feathers from the scale epidermis was seen after ectopic expression of the constitutively active β-catenin armadillo fragment (Widelitz et al, 2000). The scale epidermis responds to the growth stimuli by generating an ectopic LoGZ, which leads to new feather outgrowth. Similarly, misexpression of Delta-1 caused feather-like outgrowths from scales suggesting that an activated Notch pathway is involved (Crowe et al, 1998; Viallet et al, 1998). Retinoic acid can also produced a conversion of scales to feathers (Dhouailly et al, 1980). These data suggest that specific molecules can induce the formation of growth zones in regions where they are normally absent by maintaining the increased proliferating capacity of the growth zone. Our current data raise the intriguing possibility that Wnt 5a, Wnt 6, Wnt11, and cFz-1 may act at various stages of feather development to enhance the transcription of cyclin D1 and/or c-Myc to maintain the LoGZ (Fig 6b). Sfrp 2 shows a similar expression pattern and may function to attenuate Wnt-mediated transcriptional activation. Other alternative pathways may also be involved (Fig 6b).

Wnt members are involved in regulating the activity of the LoGZ

From our and others’ data, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway appears to be a major regulator of the LoGZ during skin appendage morphogenesis. LoGZ activity shifts as the originally radially symmetric placode becomes a short feather bud, which is divided into anterior and posterior regions. Heterogeneous molecular expression within these regions coincides with AP asymmetry. Msx-1, Msx-2, tenascin, and some Hox genes are expressed in the anterior feather bud. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-2, Wnt 7a, Delta-1, Serrate-1, Notch, and Gremlin are in the posterior domain and lead to preferential proliferation in this region (Chuong et al, 1990; Noji et al, 1993; Noveen et al, 1995; Chen et al, 1997; Crowe et al, 1998; Viallet et al, 1998; Ohyama et al, 2001). Neural cell adhesion molecule, Notch-1, and Shh are expressed in a central area between the anterior and posterior regions (Chuong and Edelman, 1985; Ting-Berreth and Chuong, 1996; Chen et al, 1997).

How do the Wnt and Fz expression patterns within the skin correspond to the LoGZ? After feather bud induction and during the short feather bud stage,Wnt 6 expression became restricted to the posterior domain coincident with the LoGZ. Wnt 5a, Fz-1, and Fz-7 expression was also coincident with the LoGZ. Wnt 11, on the other hand, was expressed in the interbud region at a distance from the LoGZ. Wnt 8c and 14 were observed throughout the feather buds without a localized pattern of expression at this stage. At the long feather bud stage, Wnt 14 and sfrp 2 were expressed in the same region as the LoGZ, whereas, Wnt 5a, Wnt 6, Wnt 11, and Fz-1, became localized to regions undergoing differentiation at this stage. In the feather follicle, β-catenin was expressed in the basal proliferating region and in the intermediate layers, which undergo differentiation. Wnt 5a, Wnt 6, Wnt 8c, Fz-1, and sfrp 2 were expressed in the follicle sheath and intermediate layer, but not in the basal layer. The intermediate layer contains cells that undergo differentiation and migrate towards the upper parts of the feather where they undergo branching morphogenesis in the ramogenic zone. The temporal and spatial Wnt gene expression patterns are often related to overt patterning and differentiation in tissues. This suggests that the Wnt may either play a second role leading toward differentiation or act to maintain a proliferating cell population in regions undergoing differentiation at this stage.

If the Wnts are involved in regulating the LoGZ, then their shifting expression patterns suggest that different Wnts sustain the LoGZ at successive stages of embryonic feather development. Hence, it may not be the action of one Wnt but rather a group of Wnts that regulate the localization and activity of the LoGZ. Changes in the response to specific Wnts would also suggest that the intracellular milieu would have to change significantly to accommodate these altered responses. It is also possible that Wnts are not at all involved in regulating the LoGZ, but are a consequence of LoGZ activity. As areas of proliferation were expanded by ectopic Wnt expression, however, it appears that Wnts are enhancing growth rather than diminishing apoptosis in this system. Furthermore, misexpression of Wnt 6 produced a localized expanded region within the feather buds, supporting the notion that multiple Wnts can sustain the LoGZ at different stages of feather development.

In summary, in this study we define the concept of a LoGZ, which can be applied to the morphogenesis of many epithelial organs. The specific temporal and spatial distribution of the LoGZ determines the shape and size of an organ. The distinct morphology of feathers helps us to analyze the regulation and function of the LoGZ. In feather morphogenesis, we found that Wnt/β-catenin activity is associated with the LoGZ. We also found that overexpression of Wnt 6 can lead to asymmetrically enlarged phenotypes within the LoGZ, or to the induction of an ectopic LoGZ or ectopic organ. A developmental perspective of the LoGZ should help us to understand the balance among the transit amplifying and differentiating cells, and how the regulation of their equilibrium may contribute to morphogenesis. In our gene transduction studies, we found that localized constitutive ectopic expression of Wnt 6 induced increased localized proliferation, forming a round ball of cells that can occur at the base, along the shaft or at the tip of feathers. The region with the phenotypic change may reflect the location of the transduced cells within the feather, and the exogenous Wnt may mimic endogenous positive regulator activity for the LoGZ.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI (R01 CA 83716; Wide-litz), NIAMS (R01 AR 42177, AR 47364; Chuong), NIH-AREA (R15-HD 36429, Burrus), NIH-MBRS (S06G 52588, Burrus), National Science Council of Taiwan and Kaoshiung Medical University (NSC-892314B037182, Chang). We would like to thank Drs McMahon and Nohno for severalWnt cDNA and Dr Dodd forWnt 8c cDNA.

REFERENCES

- Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar S. Wnt signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CW, Jung HS, Jiang TX, Chuong CM. Asymmetric expression of Notch/Delta/Serrate is associated with the anterior-posterior axis of feather buds. Dev Biol. 1997;188:181–187. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM. The making of a feather: homeoproteins, retinoids and adhesion molecules. Bioessays. 1993;15:513–521. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM, Edelman GM. Expression of cell-adhesion molecules in embryonic induction. II. Morphogenesis of adult feathers. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1027–1043. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM, Oliver G, Ting SA, Jegalian BG, Chen HM, De Robertis EM. Gradients of homeoproteins in developing feather buds. Development. 1990;110:1021–1030. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM, Widelitz RB, Ting-Berreth S, Jiang TX. Early events during skin appendage regeneration. Dependence of epithelial mesenchymal interaction and the order of molecular reappearance. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:639–646. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12584254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM, Chodankar R, Widelitz RB, Jiang TX. Evo-Devo of feathers and scales: building complex epithelial appendages. Curr Opin Dev Genet. 2000a;10:449–456. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong CM, Hou LH, Chen PJ, Wu P, Patel N, Chen Y. Dinosaur’s feather and chicken’s tooth? Tissue engineering of the integument. Eur J Dermatol Rev. 2000b;11:286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe R, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D, Niswander L. A new role for Notch and Delta in cell fate decisions: patterning the feather array. Development. 1998;125:767–775. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly D. Formation of cutaneous appendages in dermo-epidermal interactions between reptiles, birds and mammals. Roux Arch Dev Biol. 1975;177:323–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00848183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly D. Pattern formation: a primer in developmental biology. In: Malincinski GM, Bryant SV, editors. Specification of Feather and Scale Patterns. Macmillan Publications; New York: 1984. pp. 581–601. [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly D, Hardy MH, Sengel P. Formation on feathers on chick foot scales: a stage dependant morphogenetic response to retinoic acid. J Embyol Exp Morphol. 1980;58:63–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JF, Loópez A, Ros MA, Savage M, Olwin B, Simandl BK. FGF2: apical ectodermal ridge growth signal for the chick limb development. Science. 1994;264:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.7908145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat U, Das Gupta R, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. De novo hair follicle morphogenesis and hair tumors in mice expressing a truncated beta-catenin in skin. Cell. 1998;95:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold L, Ruther U. The Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 is regulated by Bmp signaling and c-June and modulates programmed cell death. EMBO J. 2002;21:966–975. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morphol. 1951;88:49–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MH. The secret life of the hair follicle. Trends Genet. 1992;8:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90350-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsken J, Vogel R, Erdmann G, Cotsarelis G, Birchmeier W. Beta-catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell. 2001;105:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang TX, Jung HS, Widelitz RB, Chuong CM. Self organization is the initial event in periodic feather patterning. Roles of signaling molecules and adhesion molecules. Development. 1999;126:4997–5009. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer E, Nelson CE, Johnson RL, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog and Fgf-4 act through a signaling cascade and feedback loop to integrate growth and patterning of the developing limb bud. Cell. 1994;79:993–1003. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood R, Bresnick J, Hornbruch A, et al. A role for FGF8 in the initiation and maintenance of vertebrate limb bud outgrowth. Curr Biol. 1995;5:797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malbon CC, Wang H, Moon RT. Wnt signaling and heterotrimeric G-proteins: strange bedfellows or a classic romance? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:589–593. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar SE, Willert K, Salinas PC, Roelink H, Nusse R, Sussman DJ, Barsh GS. WNT signaling in the control of hair growth and structure. Dev Biol. 1999;207:133–149. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BA, Fekete DM. Manipulating gene expression with replication-competent retroviruses. Methods Cell Biol. 1996;51:185–218. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto MA, Patel K, Wilkinson DG. In: In Situ Hybridization Analysis of Chick Embryos inWhole Mount andTissue Sections Methods Cell Biol. Bronner-Fraser M, editor. Vol. 51. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 291–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswander L, Tickle C, Vogel A, Martin G. Function of FGF-4 in limb development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;39:83–88. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080390113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noji S, Koyama E, Myokai F, Nohno T, Ohuchi H, Nishikawa K, Taniguchi S. Differential expression of three chick FGF receptor genes, FGFR1, FGFR2 and FGFR3, in limb and feather development. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1993;383B:645–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noramly S, Freeman A, Morgan BA. Beta-catenin signaling can initiate feather bud development. Development. 1999;126:3509–3521. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noveen A, Jiang TX, Ting-Berreth SA, Chuong CM. Homeobox genes Msx-1 and Msx-2 are associated with induction and growth of skin appendages. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:711–719. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novel G. Feather pattern stability and reorganization in cultured skin. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1973;30:605–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama A, Saito F, Ohuchi H, Noji S. Differential expression of two BMP antagonists, gremlin and Follistatin, during development of the chick feather bud. Mech Dev. 2001;100:331–333. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00525-6. Date. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presland RB, Whitbread LA, Rogers GE. Avian keratin genes: II. Chromosomal arrangement and close linkage of three gene families. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:561–576. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S, Andl T, Bagasra A, Lu MM, Epstein DJ, Morrisey EE, Millar SE. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;107:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh A, Hansen LA, Vogel JC, Udey MC. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in murine skin: possible involvement of Wnt-4 in cutaneous epithelial–mesenchymal interactions. Exp Cell Res. 1998;243:150–160. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JW., Jr The proximo-distal sequence of origin of the parts of the chick wing and the role of the ectoderm. J Exp Zool. 1998;108:363–404. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401080304. reprinted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; J Exp Zool. 1948;282:628–668. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19981215)282:6<628::aid-jez2>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengel P. Morphogenesis of Skin. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- St Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Kato Y. Epigenesis in developing avian scales.II. Cell proliferation in relation to morphogenesis and differentiation in the epidermis. J Exp Zool. 1983;225:271–283. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402250210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Berreth SA, Chuong CM. Sonic Hedgehog in feather morphogenesis induction of mesenchymal condensation and association with cell death. Dev Dyn. 1996;207:157–170. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199610)207:2<157::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viallet JP, Prin F, Olivera-Martinez I, Hirsinger E, Pourquie O, Dhouailly D. Chick Delta-1 gene expression and the formation of the feather primordia. Mech Dev. 1998;72:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels NK. Morphology and proliferation during early feather development. Dev Biol. 1965;12:131–153. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz RB, Chuong CM. Complex pattern formation: regulation of the size, number, spacing and symmetry during feather morphogenesis. Int J Dev Biol Rev. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz RB, Jiang TX, Chen CWJ, Stott NS, Chuong CM. Wnt 7a in feather morphogenesis. involvement of anterior-posterior asymmetry and proximal-distal elongation demonstrated in an in vitro reconstitution model. Development. 1999;126:2577–2587. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz RB, Jiang TX, Lu J, Chuong CM. Beta-catenin in epithelial morphogenesis: conversion of part of avian foot scales into feather buds with a mutated beta-catenin. Dev Biol. 2000;219:98–114. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]