Abstract

The most unique character of the feather is its highly ordered hierarchical branched structure1, 2. This evolutionary novelty confers flight function to birds3–5. Recent discoveries of fossils in China have prompted keen interest in the origin and evolution of feathers6–14. However, controversy arises whether the irregularly branched integumentary fibers on dinosaurs such as Sinornithosaurus are truly feathers6, 11, and whether an integumentary appendage with a major central shaft and notched edges is a non-avian feather or a proto-feather8–10. Here we take a developmental approach to analyze molecular mechanisms in feather branching morphogenesis. We have used the replication competent avian sarcoma (RCAS) retrovirus15 to efficiently deliver exogenous genes to regenerating chicken flight feather follicles. We show that the antagonistic balance between noggin and bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) plays a critical role in feather branching, with BMP4 promoting rachis formation and barb fusion, and noggin enhancing rachis and barb branching. Furthermore we show that sonic hedgehog (SHH) is essential for apoptosis of the marginal plate epithelia to become spaces between barbs. Our analyses show the molecular pathways underlying the topological transformation of feathers from cylindrical epithelia to the hierarchical branched structures, and provide first clues on the possible developmental mechanisms in the evolution of feather forms.

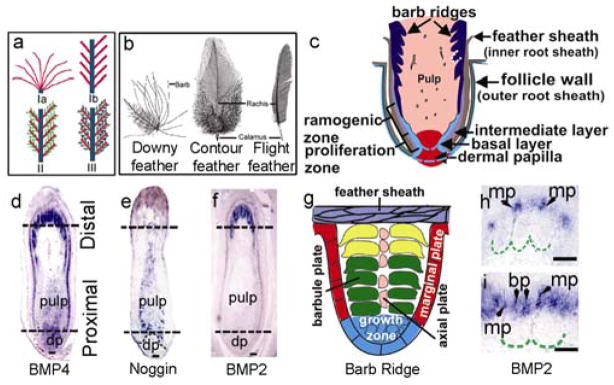

With three branching levels, i.e. from rachis to barbs; from barbs to barbules and from barbules to cilia or hooklets1 (Fig. 1a), feathers can develop into a variety of forms, including the downy, contour, flight feathers, etc. (Fig. 1b). As in hairs, the feather follicle is composed of a dermal papilla and epidermal collar (equivalent to the hair matrix, Fig. 1c–f). Through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, the epithelial cells at the bottom of the follicle undergo active proliferation (proliferation zone, Fig. 1c). Immediately above, the epithelial cells start to form the rachidial ridge and the barb ridges (ramogenic zone, Fig. 1c, f)16–19. Further distal, the barb ridge epithelia actively proliferate and differentiate to form the marginal plates, barbule plates and axial plates (Fig. 1e, central part). The barb ridges grow to form barbs, composed of the ramus and barbules, while the marginal and axial plate cells die to become the intervening space. Individual barbule plate cells undergo further cell shape changes to form the cilia and hooklets1. The barb ridges fused proximally to form the rachidial ridge, which will become the rachis. Additional cross sections (Supplementary Information Fig. 1) illustrate this process.

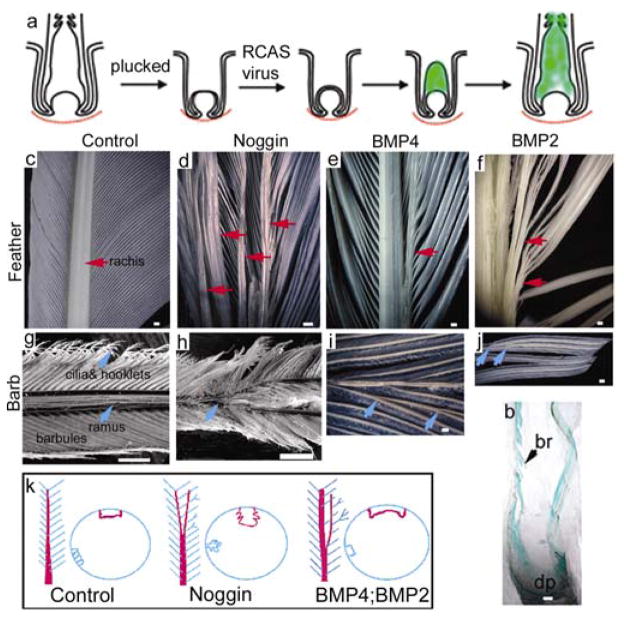

Figure 1.

Feather branching morphogenesis and gene expression. a, Diagram showing the three branching levels. Level I: Rachis (blue) branches into barbs (red). Ia, radially and Ib, bilaterally symmetric feathers. Level II: Barbs branch into barbules (green); Level III: Barbules branch into cilia and hooklets (purple). b, Different chicken feather types. c, Feather follicle structure schematic. d–f, BMP4, Noggin, and BMP2 expression patterns. The two dotted lines indicate the level of cross sections shown in Supplementary Information Fig. 2. g, Schematic drawing of feather barb. h, I, BMP2 in barb ridges. First in peripheral marginal plates (mp), then switch to barbule plates (bp). dp, dermal papilla; rz, ramogenic zone. Bar size, 100 μm.

The cellular and molecular mechanisms of epithelial organ morphogenesis are beginning to be understood20, 21. While branching morphogenesis21 has been studied in the lung and kidney, branching in the feather is unique for its exquisite order and non-randomness. In this work, we studied the role of Noggin/BMP interactions that underlie fundamental morphogenetic mechanisms22–24, in this process. We first analyzed the dynamic expressions of BMP2, BMP4 and Noggin in remiges (flight feathers) of 15-day old chicken embryos (E15) using in situ hybridization. BMP4 transcripts were detected in the dermal papilla and overlying pulp area (Fig. 1g). Later, BMP4 was expressed in the barbule plate cells (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Information Fig. 2). BMP2 was in the marginal plate epithelia in early ramogenesis25, but quickly switched to barbule plate epithelia (Fig. 1i–k). BMP4 expression in the mesenchyme appeared to form a gradient, tapering from the proximal to distal regions (Fig. 1g). Noggin transcripts were detected in the pulp cells, overlapping with BMP4 transcripts. Noggin was not expressed in the dermal papilla, but was expressed in the pulp regions adjacent to the epidermis. The expression level of noggin appeared to form a gradient from the proximal to distal pulp, with highest expression at the level of the ramogenic zone (Fig. 1h). Cross sections at the indicated locations (dotted lines) are also shown (Supplementary Information Fig. 2).

A distinct feature of the feathers is that they can regenerate repetitively after plucking. Remige feathers regenerate at a rate of about 0.5 cm/day, making them excellent recipients for RCAS mediated gene expression, which only transduces cells undergoing active mitosis 15. By injecting RCAS retroviral constructs into chick flight feather follicles after plucking (Fig. 2a), exogenous genes were mis-expressed during feather regeneration (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Information Fig. 3). Regenerated feathers injected with RCAS-LacZ virus showed no changes in the rachis, and barbs (Fig. 2c, g).

Figure 2. Phenotypic changes in feathers regenerated from follicles injected with RCAS-Noggin, BMP4, and BMP2 respectively.

a, Diagram showing the gene expression strategy. b, X-gal staining of a regenerating feather follicle injected with RCAS-LacZ 7 days ago. c–f, Splitting or merging of the rachis is indicated by red arrows. g–j, Alteration of the barbs. Abnormal branch points are indicated by blue arrows. k, Diagram illustrating the overall phenotypic changes. Bar size, 50 μm (c–f, l, j), 100 μm (g, h).

RCAS-noggin was injected into the feather follicles to perturb their BMP activity (Fig. 2d, h; n=36). Many of the regenerated feathers were severely stunted forming few barbs (33%) and even more had the rachis split into 2 or 4 mini-rachises (44%). These smaller rachises gradually converged at the proximal end (Fig. 2d). Barbs of the noggin expressing regenerated feathers were inhibited (50%) and some barbs (11%) further branched into two (Fig. 2h). Histological examination showed that the barb ridges formed irregular tree-like structures with extravagant ridge formations (Fig. 3b, f, j). The rachidial ridge was fragmented into smaller ridges (Fig. 3n).

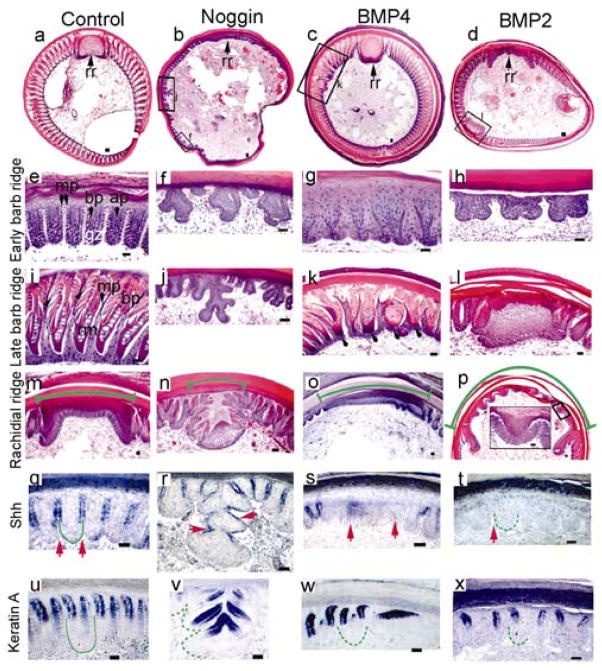

Figure 3. Analyses of feathers injected with RCAS-Noggin, -BMP4, and -BMP2 respectively.

a–d, Cross sections. e–l, Changes in barb ridges. m–p, Changes of rachidial ridge size (H&E). Rachis width (green arc). p, Enlarged indicated area (see inset) is part of the rachidial structure, not barb ridges (compare with Fig. 3e). q–t, ISH with SHH probes. Marginal plates or comparable regions (red arrows). u–x, ISH with feather keratin probes. Green lines delineate barb ridges. Dotted lines indicate abnormal barb ridges. rr, rachidial ridge. mp, marginal plate. bp, barbule plate. ap, axial plate. gz, barb ridge growth zone. Bar size, 100μm.

Regenerated feathers expressing ectopic BMPs had phenotypes that were generally opposite to that of feathers expressing exogenous noggin. Many of the RCAS-BMP4 transduced regenerated feathers were short in length, did not form barbs or a rachis (50%), and assumed a morphology similar to the calamus (feather shaft) (n=16). Several of these regenerated feathers were oversized (25%). Ectopic rachis-like structures were observed (Fig 2e, 31%). The barbs were often fused (Fig. 2i; 38%). Histological sections showed that the barb ridges failed to separate (Fig. 3c, g), the barbs fused (Fig. 3k), and the rachidial ridges were oversized (Fig. 3o). The presumptive marginal plate cells became plump (Fig. 3g) and did not die to become space (Fig. 3K).

BMP2 over-expression had similar phenotypic effects as BMP4. Feathers showed normal growth at first, then died abruptly and fell off prematurely in about 3 weeks. The sizes were usually smaller and some showed no barb formation. The rachises of the regenerated feathers were enlarged (Fig. 2f; 23%, n=26), and some feathers had ectopic rachises (23%). Some barbs fused with each other or with the rachis at various points, forming bundles (Fig. 2f, j, 77%). Histological sections showed that some barb ridges fused in pairs (Fig. 3h), suggesting that BMP2 may also function in specifying marginal plate fate, given that BMP2 was expressed transiently in peripheral marginal plates (Fig. 1j). Ectopic rachidial ridge-like structures caused by the fusion of barb ridges were observed (Fig. 3l). The rachidial ridge was extremely large, spanning nearly half of the follicle circumference (Fig. 3p). The phenotypes of regenerated feathers appeared to depend on the expression levels of the transduced genes.

While both abnormal barb ridges shared a forked appearance, the identity of barb branching or barb fusion was distinguished by counting the number and spacing of barbs. Control samples had about 6 barb ridges in the space shown in Fig. 3e–h. Noggin treated specimens had elaborately branched ridges alternating with mini-ridge forms, but the total number of ridges was unchanged. BMP2 treated specimens had only 3 forked barb ridges, suggesting that fusion occurred among the original 6 ridges.

Marginal plate cells expressed SHH26 and barbule plate cells expressed feather keratin (Fig. 3q, u; 4a). Characterization of the transduced feathers showed that noggin increased branching by increasing the number of SHH positive marginal plate cells (Fig. 3r) and perturbed the shape and arrangement of the feather keratin expressing barbule plate cells (Fig. 3v). On the other hand, epithelial over-expression of BMPs 2 and 4 altered the fate of marginal plate cells. The cells, which were plump, rather than flattened (Fig. 3 g, k) did not die and branches failed to form. SHH was not expressed (Fig. 3s, t). Some feather keratinization still took place in the barbule plate (Fig. 3w, x).

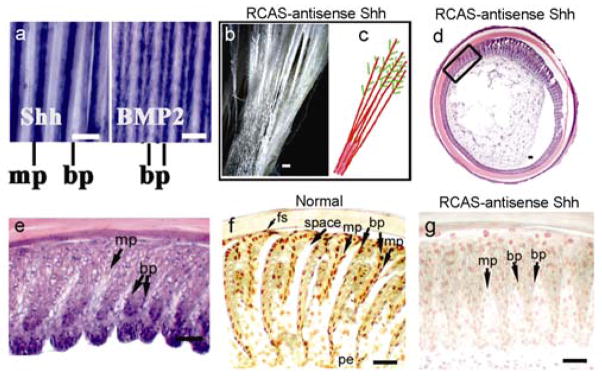

Figure 4. SHH roles in barb formation.

a, Normal feather whole mount ISH of SHH and BMP2. b, SHH inhibition by RCAS-antisense Shh or cyclopamine produced fused vanes. c, Schematic depicting changes in b. Barbs (red). Barbules (green). d, Cross sections (H&E) showed barb ridge segments that failed to separate varying from more severe (5–9 o’clock region) to less severe (1–2 o’clock). e, Enlarged indicated area in d. f, g, Apoptosis in late-differentiated barb ridges in normal and SHH suppressed follicles. bp, barbule plate; mp, marginal plate; fs, feather sheath; pe, pulp epithelium. Bar size, 100μm.

To further test the role of SHH in feather branching, we suppressed SHH using cyclopamine27 or RCAS–antisense SHH in the plucked and regenerating feather model. The two independent reagents gave similar results. The regenerated feathers showed regions where barbs fused with a web-like membrane between; therefore forming continuous feather vanes (Fig. 4b, c). Cross sections showed regions with barb ridges that failed to separate because the marginal plate cells failed to disappear (Fig. 4d, e). Suppressing SHH produced a similar phenotype as over-expressing BMP4 (compare Fig. 3g and 4e). In control feathers, TUNEL staining was positive in the marginal epithelial cells, pulp epithelium and feather sheath (Fig. 4f). The death of these cells allows feather branches to open. Suppression of SHH activity increased marginal plate cell numbers. These cells were plump in appearance and were mostly TUNEL negative (Fig. 4g). Thus, BMP over-expression suppressed SHH expression and the subsequent formation of the marginal plate. Suppression of BMP promoted branching, probably by enhancing ridge-forming activity of the basilar cells, together with specifying marginal plate fate. Therefore SHH is required for specifying marginal plate fate. Balancing the antagonistic actions of SHH and BMPs sets the number and spacing of barb ridges. However, regulation of Shh by other molecules is also possible.

Recently, the importance of the SHH/BMP “signaling module”28 in skin appendage morphogenesis was also shown by comparing chicken feather variants, duck feathers, and avian and alligator scales25. Using embryonic chicken explant cultures, they suggest that SHH is important for proliferation in proximal barb ridges, while BMP 2 suppresses SHH and promotes differentiation of distal barb ridges25. Our in vivo “transgenic feather” model using plucked/regenerated mature feather follicles allows us to analyze the late branching event that is impossible to observe in embryonic explants. This novel model should open doors for future experiments to link molecular pathways with feather forms.

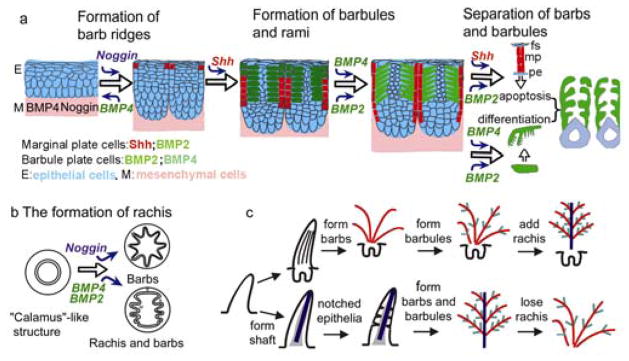

Based on these data, we propose the following model for feather branching morphogenesis (Fig. 5a, b). The multilayered epidermis can be molded into epidermal ridges by ridge forming activators (e.g., noggin) and inhibitors (e.g., BMPs) distributed in the adjacent mesenchyme. The balance between noggin and BMP4 determines the number, size and spacing of barb ridges. 1) At the proliferation zone, the level of BMP4 is much higher than that of noggin, thus the epithelial cells form a cylindrical structure. 2) At the ramogenic zone, the level of noggin in the pulp adjacent to epithelia gradually exceeds that of BMP4, thus the epithelial cells start to form multiple barb ridges. 3) The basilar layer becomes periodically arranged into SHH positive/BMP2 transiently positive marginal plate cells that die, and SHH negative barb ridge growth zone cells that proliferate. The intermediate cell layer is “cleaved” into groups of cells that become the initial barb ridge. Marginal plate cells die to ensure the formation of spaces between barb ridges1, 29. 4) The originally randomly arranged cells in the barb ridge express BMPs 2 and 4, line up and become two rows of barbule cells. These cells further differentiate to form the barbules. Barbule plate cells1 stimulated by BMP2 and 4 change shape to form the cilia and hooklets. 5) Toward the end of feather formation, noggin activity is reduced and conditions revert back to (1), forming the calamus without branches at the proximal end of the feather shaft. 6) If the noggin/BMP ratio becomes polarized in the anterior- posterior axis, the site with higher BMP activity eventually becomes the rachis, thus the bilaterally symmetric feather can form.

Figure 5. Models of feather branching and evolution of feather forms.

a, Roles of Noggin/BMP4, Shh, BMP2 in the 3 levels of feather branching. b, The ratio of noggin and BMP4 may determine the number and size of barb ridges. A localized high BMP/noggin ratio, together with a helical growth mode of barb ridges17, can lead to the formation of a rachidial ridge through fusion of barb ridges. c, Hypothetical models of the evolution of feather forms. Upper row, Barb → Rachis model. Lower row, Rachis→Barb model. The experimental data are in favor of the Barb → Rachis model.

In this work, we showed that the BMP pathway regulates the formation and inter-conversion of the barbs and rachis. We also showed that the true separation of branches required SHH activity. Other morphogens, such as FGFs and Wnts18, may also be involved in this process, and we expect them to behave under similar principles along the same pathway or with special regulation to produce feather variants.

Formation of hierarchical branches is the cardinal feature of feathers17, and therefore one of the key issues in the origin and evolution of feathers. Based on some fossil evidence, it has been proposed that a filamentous integument structure with a major central shaft and notched edges may be the prototype of feathers8–10. According to this model, the rachis would have formed first in evolution, then barbs, and finally barbules. Therefore, the rachis and barbs would be different entities and not interchangable (Fig. 5c). Alternatively, because barbs form first during development, it was proposed that barbs appeared first in integument evolution, and the rachis, a specialized form of fused barbs, appeared later as an evolutionary novelty16, 18. The fact that the barbs and rachis can be converted experimentally in the laboratory favors the Barb – Rachis model. The data here suggest that a radially symmetric feather is more primitive than the bilaterally symmetric feather in terms of molecular and developmental mechanisms, and may have been the prototype of feathers (Fig. 5c). Some fossilized primitive skin appendages on Sinornithosaurus also favor this model11. Further modulation of BMP and SHH pathways may have led to the many feather varieties seen today by regulating the number, shape and size of the rachis, barbs, and barbules1, 17, 30. This work provides the first evidence for the molecular mechanisms possibly involved in the evolution of feather branching.

Methods

Materials

Specific-pathogen-free fertilized white leghorn chicken eggs were purchased from Charles River SPAFAS (North Franklin, Connecticut). The eggs were incubated at 38°C in a humidified rotating incubator. Chicks were housed in the USC Vivarium. RCAS-noggin plasmid was from Dr. R. Johnson. RCAS-BMP2 and RCAS-BMP4 plasmids were from Dr. P. Francis-West. RCAS-LacZ plasmid encoding β-galactosidase was originally constructed by Dr. L. Yi and provided by Dr. W.-P. Wang. RCAS-Shh sense was from Dr. Tabin. RCAS-SHH antisense was produced by cutting the sense SHH plasmid with ClaI and religating the inserted SHH in the reverse orientation. The orientation was confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis (Ting-Berreth and Chuong, unpublished). Viruses were prepared and titrated24. Cyclopamine, a SHH antagonist26 provided by Dr. W. Gaffield of the USDA, was dissolved in absolute ethanol and diluted to 0.4 mg/ml in DMEM for injection (20 μl) into the regenerating feathers, using a similar procedure described for viral transduction.

Transduction of regenerating feather follicles

Chickens at 2–3 weeks of age were anesthetized with Ketamine (50 mg/kg body weight). Primary remiges I –VII were used because of their large size, distinct morphology and identity. Normally, feathers will regenerate and grow out of the follicles at about 14 days after plucking. Regenerated feathers/feather follicles were dissected at 7 days after plucking. Serial longitudinal and cross paraffin sections were cut and stained with H & E. For gene transduction, RCAS viruses were injected into the empty follicles immediately after feathers were plucked. RCAS virus propagation in follicles was verified using RCAS-LacZ virus followed by X-gal staining of cryostat sections at various days after the injection. Each follicle received about 10–20 μl of medium containing the virus (1× 105–1× 106 infectious units/ml). For preliminary studies, viruses containing the genes of interest were injected into primary remige follicles on the left wing. RCAS-LacZ virus was injected into primary remige follicles on the right wing as controls. Feather follicles injected with viruses were dissected and sectioned for histological study at 2–3 weeks after virus injection. Once distinct phenotypes were confirmed in at least 3 repeat experiments, viruses were injected to follicles on both wings for later studies. Chickens were raised in cages and observed on a daily basis over a 2-month period. The regenerated feathers were plucked and examined with a dissection or scanning EM microscope for abnormalities compared with normal primary remiges.

Histology and in situ hybridization (ISH)

Paraffin sections (5 μm) were stained with H&E or prepared for ISH following routine procedures26. Cryostat sections (10 μm) were stained with X-gal. TUNEL staining was performed using a kit (Roche). Nonradioactive ISH or section ISH was performed according to the protocol described22, 26. Digoxygenin labeled probes are generated by in vitro transcription from plasmids kindly provided by Dr. Niswander for Noggin, Dr. Francis-West for BMP2, BMP4, and Dr. Johnson for noggin and Dr. Tabin for Shh. A probe for feather keratin was prepared in our laboratory. After hybridization, sections were incubated with an anti-digoxigenin Fab conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim). Color was detected by incubating with a BM purple substrate (Boehringer Mannheim).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Sections of developing feather follicles. a, H&E stained longitudinal section of a feather follicle. H&E staining of cross sections at three different levels (proximal to distal) of the flight feather follicle (level indicated in panel a). b, proliferation, c, ramogenic, and d, more differentiated distal zones. Basilar layer cells become marginal plate and barb ridge growth zone epithelia (which give rise to more barbule plate cells and pulp epithelium, and later become the ramus, while intermediate layer cells become barbule plate cells). The peripheral epithelial layer becomes the feather sheath. mp, marginal plate; bp, barbule plate; ap, axial plate; gz, barb ridge growth zone. Bar size, 100 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Expression patterns of BMP4, BMP2 and noggin in developing feather follicles. a, d, g, b, e, h, In situ hybridization (ISH) of cross sections cut at the two levels indicated in Fig. 1 d–f (dotted lines). c, f, i, ISH of barb ridges from cross sections of embryo stage E18 flight feather follicles. Bar size, 100 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Establishment of the gene expression system in the feather follicles. a, X-gal staining of longitudinal cryostat sections of a feather regenerated from follicles at 14 days after injection with RCAS-LacZ. b, In situ hybridization using the noggin probe on a cross section of a feather regenerated from follicles 14 days after injection with RCAS-Noggin. c, Enlarged indicated area in b. Bar size, 100 μm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Marijane Ramos for help in preparing the manuscript. We thank Drs. P. Francis-West, W. Gaffield, R. Johnson, L. Niswander, C. Tabin, W.P. Wang and Li Yi, for providing reagents described in Methods. We thank Dr. R. Prum for critical comments of the manuscript. Fig. 1b is modified from Lucas and Stettenheim, 1972. This work is supported by grants from NIAMS and NSF to CMC, and NCI grant to RW.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lucas AM, Stettenheim PR, editors. Agricultural Handbook 362: Agricultural Research Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washington D.C: 1972. Avian Anatomy Integument. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuong CM. The making of a feather: Homeoproteins, retinoids and adhesion molecules. Bio Essays. 1993;15:513–521. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feduccia A. The Origin and Evolution of Birds. 2. Yale University Press; New Haven, Connecticut: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee S. The Rise of Birds. John Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, Maryland: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regal PJ. The evolutionary origin of feathers. Q Rev Biol. 1975;50:35–66. doi: 10.1086/408299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PJ, Dong ZM, Shen SN. An exceptionally well-preserved theropod dinosaur from the Yixian Formation of China. Nature. 1998;391:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu X, Tang ZL, Wang XL. A therizinorsauroid dinosaur with integumentary structures from China. Nature. 1999;399:350–354. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones TD, et al. Nonavian feathers in a late Triassic archosaur. Science. 2000;288:2202–5. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prum RO. Longisquama fossil and feather morphology. Science. 2001;291:1899–902. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5510.1899c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang F, Zhou Z. A primitive enantiornithine bird and the origin of feathers. Science. 2000;290:1955–9. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X, Zhou Z, Prum RO. Branched integumental structures in Sinornithosaurus and the origin of feathers. Nature. 2001;410:200–4. doi: 10.1038/35065589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji Q, Currie PJ, Norell MA, Ji SA. Two feathered dinosaurs from northeast China. Nature. 1998;393:753–761. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji Q, Norell MA, Gao KQ, Ji SA, Ren D. The distribution of integumentary structures in a feathered dinosaur. Nature. 2001;410:1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/35074079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norell M, et al. Modern feathers on a non-avian dinosaur. Nature. 2002;416:36–37. doi: 10.1038/416036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan BA, Fekete DM. Manipulating gene expression with replication-competent retroviruses. Methods Cell Biol. 1996;51:185–218. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prum RO. Development and evolutionary origin of feathers. J Exp Zool. 1999;285:291–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prum RO, Williamson S. Theory of the Growth and Evolution of feather shape. J Exp Zool. 2001;291:30–57. doi: 10.1002/jez.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuong CM, Chodankar R, Widelitz RB, Jiang TX. Evo-devo of feathers and scales: building complex epithelial appendages. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:449–56. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuong CM, et al. Dinosaur’s feather and Chicken’s tooth? Tissue engineering of the integument. John Ebbling lecture. Eur J Dermatology. 2001;11:286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuong C-M, editor. Molecular Basis of Epithelial Appendage Morphogenesis. Landes Bioscience; Austin: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogan BLM. Morphogenesis. Cell. 1999;96:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung HS, et al. Local inhibitory action of BMPs and their relationships with activators in feather formation: implications for periodic patterning. Dev Biol. 1998;196:11–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudley AT, Tabin CJ. Constructive antagonism in limb development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang TX, Jung HS, Widelitz RB, Chuong CM. Self organization of periodic patters by dissociated feather mesenchymal cells and the regulation of size, number and spacing of primordia. Development. 1999;126:4997–5009. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris MP, Fallon JF, Prum RO. Shh-Bmp2 signaling module and the evolutionary origin and diversification of feathers. J Exp Zool. 2002;294:160–176. doi: 10.1002/jez.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ting-Berreth SA, Chuong CM. Sonic hedgehog in feather morphogenesis: induction of mesenchymal condensation and association with cell death. Dev Dyn. 1996;207:157–170. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199610)207:2<157::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper MK, Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Teratogen-mediated inhibition of target tissue response to Shh signaling. Science. 280:1528–9. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calabretta R, Nolfi S, Parisi D, Wagner GP. Duplication of modules facilitates the evolution of functional specialization. Artif Life. 2000;6:69–84. doi: 10.1162/106454600568320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuong C-M, Edelman GM. Expression of cell adhesion molecules in embryonic induction. II. Morphogenesis of adult feathers. J Cell Biol. 101:1027–1043. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill FB. Ornithology. 2. Freeman; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Sections of developing feather follicles. a, H&E stained longitudinal section of a feather follicle. H&E staining of cross sections at three different levels (proximal to distal) of the flight feather follicle (level indicated in panel a). b, proliferation, c, ramogenic, and d, more differentiated distal zones. Basilar layer cells become marginal plate and barb ridge growth zone epithelia (which give rise to more barbule plate cells and pulp epithelium, and later become the ramus, while intermediate layer cells become barbule plate cells). The peripheral epithelial layer becomes the feather sheath. mp, marginal plate; bp, barbule plate; ap, axial plate; gz, barb ridge growth zone. Bar size, 100 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Expression patterns of BMP4, BMP2 and noggin in developing feather follicles. a, d, g, b, e, h, In situ hybridization (ISH) of cross sections cut at the two levels indicated in Fig. 1 d–f (dotted lines). c, f, i, ISH of barb ridges from cross sections of embryo stage E18 flight feather follicles. Bar size, 100 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Establishment of the gene expression system in the feather follicles. a, X-gal staining of longitudinal cryostat sections of a feather regenerated from follicles at 14 days after injection with RCAS-LacZ. b, In situ hybridization using the noggin probe on a cross section of a feather regenerated from follicles 14 days after injection with RCAS-Noggin. c, Enlarged indicated area in b. Bar size, 100 μm.