Abstract

Background

Technology-based interventions (TBIs) for substance use disorders have been increasing steadily. The mechanisms by which TBIs produce change in substance use outcomes have not been reviewed. This article is the first review of the conceptual and empirical underpinnings of the mechanisms associated with TBIs for substance use disorders.

Methods

We review the literature on potential mechanisms associated with TBIs targeting tobacco, alcohol, and poly-substance use. We did not identify TBIs targeting other drug classes and that assessed mechanisms.

Results

Research suggests that TBIs impact outcomes via similar potential mechanisms as in non-TBIs (e.g., in-person treatment), with the exception of substance use outcomes being associated with changes in the quality of coping skills. The most frequent potential mechanisms detected were self-efficacy for tobacco abstinence and perceived peer drinking for alcohol abstinence.

Conclusions

Research on mechanisms associated with TBIs is still in a nascent stage. We provide several recommendations for future work, including broadening the range of mechanisms assessed and increasing the frequency of assessment to detect temporal relations between mechanisms and outcomes. We also discuss unique challenges and opportunities afforded by technology that can advance theory, method, and clinical practice.

Keywords: mechanisms, technology, mHealth, substance use

1. INTRODUCTION

One of the most significant advances in the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) in the last decade is the use of information and digital technology to deliver evidencebased interventions. Technology-based interventions (TBIs) for SUDs constitute approaches to care delivered via computer, Internet, or mobile devices - either as stand-alone programs or as adjuncts to more traditional, in-person treatment (Marsch and Dallery, 2012; Kiluk and Carroll, 2013; Litvin et al., 2013). The significance stems not only from the potential of technology to increase access to, and cost-effectiveness of, evidence-based treatment, but also from its ability to provide personalized, on-demand access to therapeutic content and support. Research suggests that TBIs can produce outcomes that are comparable to, and potentially more costeffective than, approaches delivered by trained clinicians (Gustafson et al., 2014; Marsch and Dallery, 2012; Marsch et al., 2014).

As with all interventions, researchers should establish not just that the intervention changed substance use, but how treatment produced the changes. That is, researchers should identify the mechanisms responsible for changes in substance use. Mechanisms refer to treatment-induced changes in biological, cognitive, behavioral or environmental factors, which are then in turn responsible for drug abstinence. For example, an increase in the quality of coping skills following computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may enable cocaine abstinence (Kiluk et al., 2010), or an increase in access to reinforcers that are incompatible with substance use following a community reinforcement approach may decrease substance use (Hunter et al., 2014). Researchers can use this information about mechanisms to optimize further iterations of an intervention.

Although mechanisms can be assessed for all interventions, technology entails some unique challenges and opportunities that may make such assessment even more useful. First, assessing mechanisms should help ensure that even in light of the rapid pace of technological innovation, the key mechanisms associated with change are still present and targeted. Second, assessing mechanisms will be useful in identifying similarities and differences to more traditionally-delivered psychosocial treatments. Given the opportunity for ubiquitous access to TBIs, the nature, rate, and sustainability of changes in mechanisms may differ relative to those observed from traditional interventions. Finally, the frequent, longitudinal assessment afforded by technology-based monitoring of mechanisms and substance use outcomes may clarify the roles of mechanisms, or reveal new mechanisms in changing behavior.

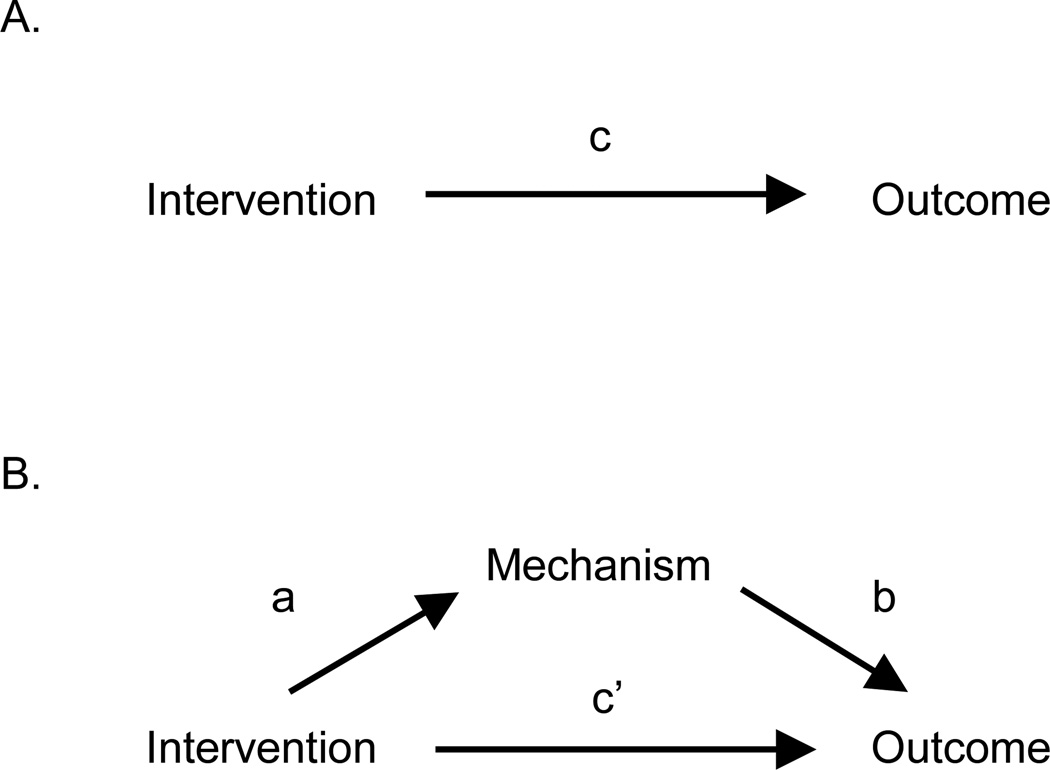

Because most research on TBIs employs randomized controlled trials (RCTs), we consider five statistical criteria to identify potential mechanisms in TBIs (Baron and Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon, 2008). Each criterion should be evaluated with reference to Figure 1. The top panel shows that some treatment produced change in an outcome, which is known as an unmediated model. The bottom panel shows a mediated model, in which treatment produces change in the outcome by first producing change in the potential mechanism, which for our purposes is synonymous with a statistical mediator. A case for a potential mechanism would be made under the following five conditions: (a) participants in treatment show significantly greater change on the outcome than controls (path c)1; (b) participants in treatment show significantly greater change on the mediator than controls (path a); (c) change in the mediator is significantly correlated with change in the outcome in the treatment condition (path b); (d) the effect of treatment on the outcome, after controlling for change in the mediator (path c′), is significantly reduced (for partial mediation) or eliminated (for complete mediation), relative to when the outcome is regressed only on the treatment condition (path c); and (e) change in the mediator occurs before change in the outcome. The first four conditions constitute Baron and Kenny’s causal steps, and the fifth condition is known as the temporal precedence criterion (Baron and Kenny, 1986; Kazdin, 2007).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of an unmediated model (A) and a mediated model (B).

In this article, we perform a narrative review of the literature on potential mechanisms in the context of TBIs for SUDs. Research on mechanisms in the treatment of SUDs is in the formative stage (Morgenstern et al., 2013). Advances are still occurring in conceptual frameworks, research designs, statistical analyses, and measures to assess various mechanisms. In addition, research on TBIs for SUDs is growing at a fast pace (Marsch and Dallery, 2012). As such, a review of mechanisms associated with TBIs is both timely and necessary to serve as a benchmark for future research, and to highlight how technology-based methods may be employed to enhance the assessment of mechanisms. To our knowledge, this is the first review of the conceptual underpinnings and empirical status of mechanisms associated with TBIs for SUDs.

2. METHODS

We conducted a literature search in PubMed using search terms associated with information and digital technology (technology, Internet, web, mobile phone, cell phone, smart phone, computer), mechanisms (mediation, mediator, mechanism), and substance use (tobacco, nicotine, smoking, cigarettes, cannabis, marijuana, alcohol, drinking, opiate, opioid, heroin, cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, drug use, addiction). We used all combinations of search terms from each category for articles published up to September, 2014, and we only included articles that statistically evaluated potential mechanisms of psychosocial treatments (i.e., a formal mediation analysis). To maintain a focus on advances in information technology and due to space constraints, we excluded studies that relied solely on more traditional, phone-based counseling. In addition, we restricted our review to potential mechanisms that represented theory-derived mechanisms, and not generic, treatment process mediators such as level of engagement or perceived relevance of the content of the intervention. Our search yielded 482 potential studies. We evaluated the titles and abstracts of each article and selected 66 for full-text review. We searched these articles’ references sections and identified an additional 95 relevant articles. Of the 161 articles we identified for review, 37 were not treatment studies (e.g., reviews, commentaries), 77 did not include formal mediation analyses, 12 did not report substance use treatment outcomes, 10 did not meet our definition of being technology-based treatments, and 11 focused on treatment process mediators. These articles were excluded, leaving 15 studies. Three additional studies were identified by the authors independently after the literature search. Table 1 presents information about each study we identified in our literature search.

Table 1.

Technology-based interventions targeting tobacco, alcohol, and substance use and mechanisms assessed

| Authors (date) Tobacco |

Treatment | Sample | Outcome | Mechanism* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brendryen and Kraft (2008) | Multi-platform digital media intervention |

396 adult smokers |

Abstinence at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months | Self-efficacy |

| Brendryen et al. (2008) | Multi-platform digital media intervention |

290 adult smokers |

Abstinence at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months |

Self-efficacy Coping planning |

| Bricker et al. (2013) | Web-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

222 adult smokers |

30-day abstinence at 3 months |

Acceptance of physical, cognitive, and emotional smoking cues |

| Buller et al. (2008) | Tailored web-based educational intervention |

3311 adolescent smokers |

30-day abstinence |

Perceptions of peer smoking, perceptions of adult smoking, attitudes about smoking, confidence in not smoking in the future, importance of not smoking |

| Danaher et al. (2008) | Multi-component web- based intervention |

402 smokeless tobacco users |

Abstinence at 3 and 6 months | Self-efficacy |

| Wangberg et al. (2011) | Tailored multi- component web- based intervention |

2298 adult smokers |

7-day abstinence at 1, 3, and 12 months | Self-efficacy |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Barnett et al. (2007) | Computer-delivered intervention |

227 college problem drinkers |

Number of drinking days, number of heavy drinking days, average number of drinks per drinking day, average BAC |

Motivation to change, perception of peer drinking, strategies |

| Doumas et al. (2009) | Web-based normative feedback |

77 college problem drinkers |

Quantity of weekly drinking, peak alcohol consumption, frequency of drinking to intoxication, peak alcohol consumption, frequency of drinking to intoxication |

Perception of peer drinking |

| Gustafson et al. (2014) | Interactive smartphone application |

349 alcohol- dependent adults |

Frequency of risky drinking |

Perceived competence, relatedness, autonomous motivation |

| Murphy et al. (2010) | Web-based normative feedback |

107 college heavy drinkers |

Peak alcohol consumption, quantity of weekly drinking, past monthly heavy drinking |

Motivation to change, normative discrepancy, self-ideal discrepancy |

| Neighbors et al. (2004) | Computer-delivered normative feedback |

252 college heavy drinkers |

Overall consumption, peak alcohol consumption, typical weekly drinking, alcohol-related problems, typical weekly drinking |

Perception of peer drinking |

| Neighbors et al. (2006) | Computer-delivered normative feedback |

217 college heavy drinkers |

Typical weekly drinking, alcohol-related problems |

Perceptions of peer drinking |

| Neighbors et al. (2009) | Web-based normative feedback |

295 college drinkers |

Number of drinks on 21st birthday | Perceptions of peer drinking |

| Neighbors et al. (2010) | Web-based normative feedback |

898 college heavy drinkers |

Quantity of weekly drinking, frequency of heavy episodic drinking |

Perceptions of peer drinking |

| Voogt et al. (2014b) | Web-based brief intervention |

907 college heavy drinkers |

Weekly alcohol consumption, frequency of binge drinking |

Social pressure drinking refusal self- efficacy, opportunity drinking refusal self- efficacy, emotional drinking refusal self- efficacy |

| Walters et al. (2007) | Web-based normative feedback |

106 college heavy drinkers |

Quantity of weekly drinking, peak alcohol consumption, peak alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems |

Perceptions of peer drinking |

| Williams et al. (2009) | Two multi-component web-based interventions |

3051 military personnel |

Number of drinking days, drinks per occasion, days perceived drunk, binge drinking history, binge drinking frequency, heavy drinking history, peak BAC |

Descriptive norms (quantity), descriptive norms (frequency), alcohol motivational balance, perceived risk of heavy use, reasons to limit use, readiness to change, avoidant coping, active coping |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Kiluk et al. (2010) | Computer-based CBT | 52 drug users in outpatient treatment |

Frequency of substance use, longest duration of abstinence |

Quality of coping skills, quantity of coping skills |

Note: Mediators in italics were identified as potential mechanisms

3. RESULTS

3.1 Tobacco

The number of TBIs for smoking cessation is large and growing. Several reviews suggest that TBIs can promote tobacco abstinence (Kaplan and Stone, 2013; Pulverman and Yellowlees, 2014; Riley et al., 2011), but there are relatively few studies that have assessed potential mechanisms responsible for changes in smoking.

Two RCTs evaluated an intensive, 54-week Internet- and mobile-phone-based program called “Happy Ending” (Brendryen et al., 2008; Brendryen and Kraft, 2008). The intervention included over 400 contacts by email, web-pages, interactive voice response, and short message service (SMS) technology. Content and frequency of contact was customized based on the phase of the study. For example, the first 11 weeks the intervention was relatively intensive and included daily web, SMS, and audio contacts. After week 11, the frequency tapered, and the intervention focused more on lapse and relapse prevention. The content of the intervention was derived from cognitive behavioral theory (e.g., developing self-awareness, problem solving skills, goal setting and planning, and coping skills) and social cognitive theory (e.g., increasing self-efficacy in quitting and managing tempting situations).

In the first RCT, participants received Happy Ending or a self-help booklet (Brendryen and Kraft, 2008). All participants were offered free nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Participants in Happy Ending were more likely to be abstinent at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months compared to control participants (self-reported repeated point abstinence rates were 22.3% vs. 13.1%, respectively). Although NRT use was higher in Happy Ending than controls, results of a mediation analysis did not suggest that higher NRT use mediated outcomes. Analysis also revealed a complete mediation effect of self-efficacy, measured at 1 month, on abstinence.

Because willingness to use NRT may have limited the generalizability of the results of the previous trial, a second RCT was conducted in which NRT was not offered (Brendryen et al., 2008). Higher repeated point abstinence was found in the Happy Ending compared to the control group (20% versus 7%, respectively). The authors also assessed whether precessation self-efficacy and coping planning (e.g., perceived ability to overcome anticipated barriers to cessation) mediated treatment effects. Although Happy Ending increased both self-efficacy and coping planning, only self-efficacy was found to mediate abstinence at 1 month. There were no mediation effects when repeated abstinence (i.e., abstinence at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months) was the outcome.

Two studies evaluated the potential mechanisms associated with tailored cessation interventions in adults (Wangberg et al., 2011) and adolescents (Buller et al., 2008). Tailoring refers to three general procedures: personalization based on characteristics such as age, gender, first name; adaptation based on theory-derived constructs such as self-efficacy; and feedback based on responses to questionnaires and other interactive content (Dijkstra, 2005). Wangberg et al. used all three procedures in an online intervention, and compared the tailored intervention to a static website that provided educational information on smoking. The adaptation procedure sought to enhance self-efficacy and confidence about refraining from smoking in different situations. The tailored intervention produced statistically significant higher abstinence rates than the static website at 1 month (15.2% vs. 9%) and 3 months (13.5% vs. 9%), but not at 12 months (11% vs. 12%). Wangberg et al. also found that self-efficacy measured at one month partially mediated outcomes at 3 months.

A second study assessed the effects of a tailored, Internet-based intervention on smoking prevention in two samples of adolescents – one in Australia and one in the United States (Buller et al., 2008). The intervention was delivered in schools during six, 45–60 minute sessions over the course of one month. The content was based on social learning theory, and aimed to create positive outcome expectancies for not smoking, negative outcome expectations for continued smoking, and increased self-efficacy for avoiding or stopping smoking. In addition, the content aimed to alter normative beliefs about the prevalence of smoking by peers and adults. Schools in the control group received standard health education. Self-reported smoking over the past 30 days decreased slightly in the intervention group (13.1% to 12.7%) while it increased slightly in the control group (11.2% to 14.3%). This pre-post difference between groups was statistically significant. Of those who reported smoking before the intervention, 4.9% reported they had not smoked following the intervention compared to 3.0% in the control group. The program had no significant effects on smoking prevalence in the American sample. Overall, the authors noted that this Internet-based program might have limited practical utility. The list of potential mediators of outcomes is presented in Table 1. Of those tested, only perceived norms for Australian children trying cigarettes mediated outcomes.

Another web-based intervention targeted smokeless tobacco (Danaher et al., 2008). The intervention was based on social cognitive theory, and focused on strategies to address behavior, cognition, and environmental factors. The website contained text based on these strategies, interactive activities, testimonial videos, and an ask-an-expert and peer forum. The control group was exposed to an information-only website. Self-reported repeated point abstinence at 3 and 6 months was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to control (16.1% vs. 8.9%). Increased self-efficacy from baseline to 6 weeks was a significant mediator of abstinence at 3 and 6 months.

Bricker et al. (2013) developed and tested the first web-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) intervention for smoking cessation. ACT is based on modern learning theory that posits that greater acceptance of thoughts and feelings can weaken their influence over subsequent action. ACT also entails identifying values and behavior change procedures to commit to these values (e.g., smoking cessation). Core processes of ACT were embedded in the website by using personalized quit plans along with videos of former smokers sharing success stories and modeling acceptance. Compared to the National Cancer Institute’s Smokefree.gov site, participants in the ACT group spent more time on the site (18.98 vs. 10.72 min) and were more satisfied (74% vs. 42%). At a 3-month follow-up, more participants were abstinent in the ACT group relative to control (25% versus 10%). Increases in acceptance of physical, cognitive, and emotional cues to smoke mediated these outcomes. Acceptance processes were assessed at baseline and at the 3-month follow-up.

3.2 Alcohol

Compared to tobacco, more studies have examined mechanisms in TBIs targeting alcohol use. All but two of the interventions we identified in our review focused on reducing drinking among college students using single-session, brief interventions. Thus, although the studies below revealed several mechanisms of TBIs, they represent a specific subset of possible target populations and available technologies to treat alcohol use.

Barnett et al. (2007) compared a computer-delivered intervention (CDI) and an in-person brief motivational interviewing (BMI) session on drinking outcomes in college students. The BMI session included personalized normative feedback (PNF), advice, and strategies to prevent alcohol-related harms. The CDI, Alcohol 101, allowed participants to click through a “virtual party” with content similar to the BMI but not personalized. There were no significant differences at 3 months on patterns of alcohol use, and results at the 12 month follow-up were equivocal. BMI was more effective at decreasing overall consumption (0.28 decrease vs. 0.42 increase) but CDI was more effective at decreasing the number of drinking days (0.16 decrease vs. 1.14 increase). None of the tested mediators (see Table 1) explained the superior outcome for the CDI.

Neighbors and colleagues explored the mechanisms mediating technology-based PNF among heavy college drinkers (Neighbors et al., 2004, 2009, 2010, 2006). PNF interventions are founded on Social Norming Theory, which attributes problematic alcohol use to overestimation of peer drinking norms. In two lab-based studies,Neighbors et al. (2006) randomly assigned students to a computer-based PNF or assessment-only condition and measured changes in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems at a 2-month follow-up or at a 3 and 6-month follow-up (Neighbors et al., 2004). The PNF program displayed how much s/he thinks his or her peers typically drink, how much a typical peer actually drinks, and a percentile ranking. Students assigned to the computerized PNF reported significant reductions in alcohol use but not alcohol-related problems at all follow-up time points in both studies. Reductions in perceived normative drinking from baseline to 3 months significantly mediated the treatment effect observed at 6 months (Neighbors et al., 2004) as did changes in perceived norms from baseline to 2-months for the 2-month follow-up (Neighbors et al., 2006). Similar findings have been documented in web-based PNF applications and for even longer follow-up periods (Neighbors et al., 2010).

The work by Neighbors and colleagues has been extended and replicated by other researchers. In one study (Doumas et al., 2009), college students received web-based PNF or a web-based educational intervention. The web-based PNF program (“Check Your Drinking”) included multiple types of personalized feedback supplemental to PNF on drinking levels. For example, students received tailored information on the amount of money they spend on alcohol and how many calories they consume by drinking. Participants who completed the web-based PNF reported lower weekly alcohol consumption (40% vs. 18% reduction), lower peak drinking quantities (21% vs. 5% reduction), and reduced frequency of drinking to intoxication (19% vs. 10%) at 1-month follow-up compared to the web-based education group. As predicted, reductions in perceived normative peer drinking mediated this intervention effect.

Walters et al. (2007) assigned college students to receive e-CHUG or assessment-only and measured weekly drinking, peak BAC, and alcohol-related problems at an 8- and 16-week follow-up. Students who received the e-CHUG program reduced their weekly drinking 43% and their peak BAC 50% more relative to the control group at 8 weeks. Moreover, mediation analyses showed that reductions in perceived normative peer drinking were responsible for the observed treatment effect. However, there were no differences in drinking outcomes at 16 weeks or in alcohol-related problems at any follow-up periods.

More recently,Voogt et al. (2014a) developed and tested a theory-based online PNF and compared it to an assessment-only condition. The What Do You Drink (WDYD) program contains two parts and is based on MI principles and the I-Change model. Part one provides PNF to increase awareness of drinking problems, consequences, and risks. Part 2 focuses on goal setting, action planning, and increasing drinking refusal self-efficacy (DRSE). Alcohol consumption, frequency of binge drinking, and DRSEs were assessed weekly using Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) for 1 month prior to the intervention and for 6 months post-intervention. EMA allows for frequent and repeated real-time assessment of self-report data in naturalistic settings. Outcomes were aggregated at 1, 3, and 6 months follow-up. Relative to the assessment-only condition, WDYD prevented increases in weekly drinking and frequency of binge drinking, which were sustained for 3 and 6 months, respectively (Voogt et al., 2014b). DRSE related to emotions and opportunities did not mediate WDYD’s effects, however DRSE for social pressure increased in the WDYD group and was associated with reductions in weekly drinking and frequency of binge drinking.

We identified only two studies that investigated mechanisms associated with TBIs that targeted non-college samples. Williams et al. (2009) tested two online programs, the Drinker’s Check-Up (DCU) and Alcohol Savvy (AS), relative to a control group among military personnel. Each program relied on Social Learning Theory, the Health Belief Model, and the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change. The DCU was also based on MI principles and was designed to reduce drinking change ambivalence. It focused on consequences of drinking, strategies to reduce drinking, and PNF. Similarly, AS attempts to change awareness, motivation, and knowledge about alcohol use. AS also includes modules on reducing and coping with stress. AS did not induce positive changes in alcohol use. However, DCU reduced six of the seven measured negative drinking outcomes at 1 month follow-up. At 6-months follow-up, only two drinking outcome effects remained significant (number of drinking days and drinks per occasion). Two mediation models (concurrent and lagged) were explored. Reductions in perceived norms about the quantity of peer drinking mediated some but not all of the intervention effects in both models. Reductions in perceived norms about drinking frequency mediated outcomes for the concurrent but not the lagged model.

A recent RCT (Gustafson et al., 2014) investigated whether an interactive smartphone application could reduce the frequency of risky drinking days in adults newly discharged from inpatient treatment for alcohol dependence. Participants received treatment as usual with or without access to the Addiction-Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (ACHESS). Treatment as usual included group counseling using CBT, MI, case management, and attendance at AA meetings. The A-CHESS application contained static features (e.g., sober day counter, motivational quotes about sobriety) and interactive components (e.g., GPS-based alerts when entering high-risk drinking areas, panic button that alerts a counselor or friend of imminent relapse). Development of the A-CHESS application was driven by Self-determination Theory, which targets three potential mechanisms: feeling close to others, feeling internally motivated to act, and perceiving oneself as competent. A-CHESS participants reported fewer risky drinking days at 4 and 12 months follow-up but not at 8 months. The only significant mediator of A-CHESS was increases in perceived competence at 4 months, which mediated changes in risky drinking at 8 months.

3.3 Substance use

We identified only one study exploring mechanisms of a TBI for illicit substance use (Kiluk et al., 2010). Kiluk et al. examined the effects of Computer-based Training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT4CBT) that consisted of multimedia lessons on drug abstinence among individuals seeking drug treatment at a community outpatient center. Participants received standard treatment with or without biweekly access to the CBT4CBT program. Individuals who received the computer-based adjunct submitted significantly less positive urine samples (29% vs. 58%) and achieved longer durations of abstinence (26 vs. 16 days). Participants took part in role-play situation tests to assess coping skills targeted by the interventions prior to, following, and 3-months post-treatment. Participant responses were recorded and rated independently for both quality and quantity. Responses for participants who completed the CBT4CBT program were not more frequent but were rated higher qualitatively. Mediation analyses revealed that the quality of participant responses mediated treatment effects on longest duration of abstinence.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 Mechanisms associated with technology-based interventions

Overall, TBIs targeting tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug abstinence can produce superior outcomes relative to control conditions. However, for some TBIs there was no significant effect (Williams et al., 2009), differences were modest (Wangberg et al., 2011), or the outcomes were mixed (Barnett et al., 2007; Buller et al., 2008). One study reported lower efficacy of a TBI relative to an in-person intervention (Barnett et al., 2007). We did not identify any studies that directly compared traditionally-delivered treatments with their technology-based equivalents and that assessed mechanisms. Such comparisons, with equivalent treatment components and fidelity, will be informative.

Several studies that focused on tobacco use suggested that self-efficacy may mediate effects of TBIs. Other potential mechanisms (see Table 1) included coping planning, perceptions of peer smoking, and acceptance of physical, cognitive, and emotional cues to smoke. Interventions targeting alcohol focused on different mechanisms, and suggested that perceived competence may be a potential mechanism for recovering alcohol-dependent adults. Among college-aged individuals, perceptions of peer drinking and possibly drinking refusal self-efficacy mediated intervention effects on drinking outcomes. Although space precludes a discussion of how participant characteristics may interact with these mechanisms, younger age may be more associated with perceived norms than older age. Finally, the quality of coping skills mediated drug outcomes following a computerized cognitive-behavioral intervention targeting substance use.

Across the 17 studies we reviewed, researchers employed different statistical approaches to detect potential mechanisms (see Preacher, 2015 for a recent review of statistical methods). Most studies inferred the mediation effect by using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) causal steps (Barnett et al., 2007; Brendryn and Kraft, 2008; Brendryen et al., 2008; Doumas et al., 2009; Neighbors et al., 2004, 2006, Walters et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2010 used a longitudinal mediation approach, see Kenny et al., 2004). Several studies directly tested the significance of the mediation effect (i.e., the product of indirect effects2) in addition to a set of regressions or path analysis for causal steps (Bricker et al, 2013; Buller et al., 2008; Danaher et al., 2008; Kiluk et al., 2010; Wangberg et al., 2011; Gustafson et al., 2014; Williams et al, 2009). One study used latent growth curve modeling (Voogt et al, 2014b). None of the studies we reviewed satisfied the temporal precedence criterion. In several studies, the potential mechanisms and outcomes were measured at the same time point (Bricker et al., 2013; Buller et al., 2008; Doumas et al., 2009; Neighbors et al., 2009, 2006; Walters et al., 2007), which rules out the possibility of identifying a temporal relation. In other studies (Danaher et al., 2008; Gustafson et al., 2014; Neighbors et al., 2004; Wangberg et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2009), potential mechanisms were assessed at baseline and again during treatment and prior to outcomes (e.g., assessments of mechanisms and outcomes were separated by several weeks), but these temporal gaps leave open the possibility that substance use outcomes changed prior to the potential mechanism and not vice versa. Thus, the temporal precedence criterion remains the ‘Achilles’ heel of treatment studies” (Kazdin, 2007, p. 5).

The magnitude of mediated effects varied across studies, and in some cases effect sizes for the mediated effect were not reported (Brendryen et al., 2008; Wangberg et al., 2011). The magnitude of the mediated effect is an important factor to consider, and unfortunately little attention has been paid to quantifying and reporting effect sizes (Fairchild et al, 2009; Preacher and Kelley, 2011). Even when effect sizes are reported, however, the practical importance of these effects must be based on non-statistical reasoning. This reasoning must take into account the importance of the mechanism and the outcome measure, the costs and feasibility of the intervention, and comparisons to other available treatments (Preacher and Kelley, 2011). Future research should explicitly discuss the magnitude of the mediated effect and its practical importance (Fairchild et al., 2009; Preacher and Kelley, 2011).

One noteworthy feature of the studies reviewed above is that they used theory to guide both the implementation of the treatment and the selection of potential mechanisms. For example, most of the studies on smoking cessation were generated based on social cognitive theory, and therefore assessed a key theoretical construct: self-efficacy. Across studies, however, identically named constructs were sometimes assessed using different measures. For example,Wangberg et al. (2011) used a 12-item scale called the "Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire," which contains two 6-item subscales measuring confidence in ability to refrain from smoking when facing internal stimuli (e.g., feeling depressed) and external stimuli (e.g., being with smokers). In contrast, the two studies evaluating Happy Ending (Brendryen et al., 2008; Brendryen and Kraft, 2008) used an average of two items measuring self-efficacy (specific items were not reported).

Although these measures of self-efficacy may overlap conceptually, different measures for the same construct will hinder our ability to evaluate the replicability and generality of effects of mechanisms. Unfortunately, the number of measures for identical constructs, or identically-named constructs, seems to be increasing (Larsen et al., 2013). A recent review found a dearth of commonality among measures used in the substance use literature (Conway et al., 2014). To enhance commonality, the National Cancer Institute launched the Grid-Enabled Measures (GEM) database (Rabin et al., 2012), which seeks to include high-quality and a reduced number of measures. Similarly, the National Institute on Drug Abuse developed the PhenX toolkit of measures (Conway et al., 2014). Consistency in measures will be important in comparisons between TBIs and their traditionally-delivered counterparts, and in establishing the generality of these interventions across settings, populations, and technological platforms.

Overall, the potential mechanisms revealed for TBIs are consistent with findings from similar, non-TBIs (e.g., in-person treatment). First, previous studies have identified the same mediators for some of the same drug outcomes (i.e., self-efficacy for smoking; Gwaltney et al., 2009), perceived peer drinking for alcohol (Borsari and Carey, 2000). Thus, with the exception of the quality of coping skills, technology-based research has not revealed novel mechanisms of behavior change. Second, like previous studies, most TBIs focused on a limited number of potential mechanisms. This is not necessarily a shortcoming from the perspective of theory testing, but it does limit the ability to assess the specificity of a proposed mechanism. That is, a case for a proposed mechanism can be strengthened if the proposed mechanism is uniquely associated with a change in outcomes, and other potential mechanisms are not associated (Kazdin, 2007; Nock, 2007). Third, and also consistent with studies on non-technology based interventions, no study established the temporal precedence of a potential mechanism.

4.2 Mechanisms, technology, and the future: Challenges and opportunities

As we noted earlier, the study of mechanisms is still in the formative stage, but it is growing at a fast pace. In light of this review, we offer several observations and suggestions for the future study of mechanisms involved in TBIs. Although some suggestions are consistent with other reviews for non-technology-based interventions (Collins et al., 2013; Larsen et al., 2013; Magill and Longabaugh, 2013; Moos, 2007), we think that technology-based methods offer unique – and in some cases unprecedented - opportunities to address these suggestions.

4.2.1 Broadening the range of potential mechanisms while harmonizing measures

Several authors have recommended that researchers should assess a broader range of potential mechanisms (Baker et al., 2014; Moos, 2007). In part, their recommendations are a result of the growing recognition that many theory-derived accounts of behavior change are oversimplified. As Kazdin and Nock (2003) observed, “‘there is not likely to be a single mechanism for a technique and that two [participants] in the same treatment conceivably could respond for different reasons’” (p. 1127)). Similarly, Longabough (2007) observed: “Given that different people change for different reasons, and the same person may change at different times for different reasons, it is unlikely that focusing on single mediators of change one at a time, applicable to all clients at all times will, by itself, give us much traction” (p. 31S). One possibility to broaden the range of mechanisms assessed is to employ an integrated battery of measures across technology-based platforms, populations, and settings (Moos, 2007).

In addition to reflecting a more comprehensive and complex picture of mechanisms of change, as these measures are used consistently across studies it will enable a better understanding of the conditions under which replications do and do not occur. For example, patient characteristics (e.g., based on gender, cognitive functioning, level of substance involvement) or technology-based platforms (e.g., Internet vs. mobile) may predict, or moderate, the effects of particular mediators on outcomes. As noted byBaker et al. (2014) assessing diverse mechanisms “can tell us not only what an intervention is doing, but also what it is not doing.” Such information will be important both for theory and intervention development.

4.2.2 Employing technology to increase the frequency of assessment

Establishing temporal precedence is one of the main challenges in research on mechanisms of behavior change (Baraldi et al., 2014). This may not be surprising given the state of knowledge regarding mechanisms: researchers are still uncovering which mechanisms are relevant for TBIs and therefore warrant more careful scrutiny. Once potential mechanisms are identified, however, more frequent assessment of both the mechanism(s) and outcome(s) will be necessary. The optimal timings of these assessments will depend on theoretical and empirical knowledge about the temporal dynamics between changes in specific mechanisms and behavior (see Collins and Graham, 2002 for a further discussion). Obtaining this knowledge means more frequent assessment.

Several technology-based methods can be harnessed to provide frequent, longitudinal assessment in naturalistic contexts. One example is EMA (Shiffman et al., 2008). For instance,McCarthy et al. (2008) incorporated EMA up to 7 times per day for 2 weeks preceding and 4 weeks following a quit attempt using bupropion to assess potential mechanisms (i.e., withdrawal, negative/positive affect, and craving) associated with cigarette smoking outcomes. Participants also completed a battery of retrospective measures each evening. McCarthy et al. found that bupropion’s treatment effects were not due to withdrawal but were partially mediated by reducing cigarette cravings and increasing positive affect. Interestingly, whether craving was a significant mediator depended on the measurement interval: craving, when measured in the evening and retrospectively, was not a significant mediator of bupropion, but when it was measured frequently using EMA it was identified as a mediator. This suggests that even daily assessments may be inadequate to detect certain mechanisms (see also Berkman et al., 2011; Kuerbis et al., 2013). Additional research using EMA has assessed the temporal relation between self-efficacy and smoking cessation. Perkins et al. (2012) assessed both self-efficacy and abstinence on a daily basis. They found a bidirectional relationship: self-efficacy predicted next day abstinence, and abstinence predicted next day self-efficacy. Collectively, these studies highlight the complexity and dynamic nature of potential mechanisms of change in substance abuse research. Of course, some potential mechanisms may be more stable over time (e.g., social support), but the point is that technology may allow a more nuanced and well-suited portrait of the relation between mechanisms and outcomes.

Frequent assessment will be necessary for potential mechanisms but also for monitoring substance use outcomes. Technology may aid in this domain. For example, advances in biochemical detection for some substances may be employed to frequently assess outcomes (Dallery et al., in press). Several researchers have employed Internet- and mobile-phone-based video verification of smoking via breath carbon monoxide and alcohol via breathalyzers (Alessi and Petry, 2013; Dallery et al., 2007, 2013). Sweat-based assessment is another possibility to detect alcohol use (Gambelunghe et al., 2013). One potential concern with frequent assessment of variables is the burden participants may face and thus the likelihood of completing frequent assessments, but research suggests good adherence to such protocols, both for EMA (Shiffman et al., 2008) and video-based monitoring of smoking and alcohol status (Alessi and Petry, 2013; Dallery et al., 2007, 2013). Another concern is that frequent assessment may result in reactivity. Research thus far is inconclusive about the role of reactivity, at least in studies using EMA (e.g., Rowan et al 2007).

If researchers employ more frequent assessment of mediators and outcomes, additional analytic techniques will be necessary to model the dynamic interactions between variables (Voogt et al., 2014b). In one illustrative study (Stice et al., 2011), a number of potential mechanisms of change in body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms were assessed during each week of a 4-week program in a sample of adolescent females. The authors estimated the slopes of the changes in both mechanisms and outcomes over the 4- week period, and evaluated whether meaningful change in the mediator preceded changes in the outcomes. For all four outcomes, hypothesized change in the mediators preceded changes in the outcomes for the majority of participants. In addition, more intensive, time-varying relations between mechanisms and outcomes can be assessed using longitudinal assessment procedures such as EMA. For example,Shinkyo et al. (2014) assessed fine-grained relations between negative affect and smoking urge (a proxy for smoking), and employed a novel statistical technique to examine relations between the two (a generalized time-varying effect model; see Tan et al. 2012).

4.3 Conclusions: Harnessing technology to advance the science of mechanisms

The promise of technology extends beyond intervention delivery. Technology permits a new vantage point from which to view the complex relations between interventions, mechanisms, and outcomes. In addition, technology encourages us to think about future methods, theories, and clinical practices.

New methods include how mechanisms and behavior can be assessed, and how experiments can be conducted to evaluate the causal roles of mechanisms (Spencer et al., 2005). Technology can help detect a variety of behavioral and environmental factors such as the presence of people using mobile-phone-based microphones (Lane et al., 2011), mood using wearable physiological sensors (Burns et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2012), and engagement in nondrug activities based on tagging locations for such activity via GPS (Dallery et al., in press). Variations of these methods may also permit tests of new theories of addiction and associated mechanisms. For example,Morganstern et al. (2013) advocated for evaluating new models of choice and decision making by examining neurobehavioral mechanisms associated with impulsive versus self-controlled choice (see also Kiluk and Carroll, 2013). Because assessing neural mechanisms is expensive and time consuming (e.g., via functional magnetic resonance imaging), an alternative strategy may entail using proxy, somatic measures of neurobehavioral functioning using wearable sensors to detect physiological arousal (Naqvi and Bechara, 2010). Several researchers have evaluated sensor-based methods to detect specific states of arousal in combination with iterative machine learning techniques (Boyer et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012). Future research should explore whether these or similar methods will be useful in exploring neurobehavioral mechanisms.

Technology also entails some advantages in how experiments can be conducted to evaluate mechanisms. Many TBIs include multiple components as part of an overall treatment package (Dallery et al., 2014). By comparing all components in the package to a control condition (i.e., an RCT), the researcher loses some resolution about which components may be most influential. One advantage of many technology-based methods is that the components can be delivered in isolation, with high fidelity, to different groups of participants. For example mobile phones may permit access to social support, information about peer drinking, and/or messages to promote self-efficacy. New methodological frameworks have been developed to permit efficient comparisons between components (Collins et al., 2013b). In addition, specific components can be identified that produce the greatest changes in mechanisms, which should further increase the efficacy and efficiency of a technology-based intervention (Dallery et al., in press). Experimental designs can also leverage the ability of technology to generate a continuous time-series of behavior. Single-case experiments, for example, require a time-series and can be used to experimentally manipulate potential mechanisms (Dallery et al., 2013). Indeed, one of the main criteria to build a case for a mechanism, as outlined by Kazdin and Nock (2003), is experimental validation (i.e., experimentally manipulating the mechanism and observing effects on outcomes). Another criterion to build a case for a mechanism - showing that more of the mechanism produces more of the outcome - can be evaluated using parametric analysis in the context of a single-case experiment (Dallery and Raiff, 2014).

Advances in methodology afforded by technology will propel advances in theory. Several authors have noted that theories of behavior change have yet to catch up to advances in technology. Riley et al. (2011) argued for new and revised conceptual frameworks “that have dynamic, regulatory system components to guide rapid intervention adaptation based on the individual’s current and past behavior and situational context”. Dallery et al. (in press) describe how relevant behavior and situational contexts may be identified and adapted based on modern learning theory. Relevant behavior may also be captured by new neurobehavioral models of decision making (Kiluk and Carroll, 2013; Morgenstern et al., 2013).

Advances in method and theory will mean very little if they do not impact clinical practice. In light of the considerations above, a one-size fits all approach to treatment may become a relic of the past. Determining what “fits” in the realm of TBIs may become a matter of continuous, technology-based assessment of an individual’s behavior, mechanisms of change, and then subsequent intervention adaptation (Dallery and Raiff, 2014; Winett et al., 2014). Topol (2012) outlined a similar outcome in The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care. Topol predicted that the emergence of mobile phones, Internet connectivity, digital sensors, and social networks will lead to a new medical science focused on personalized diagnostics and treatment in real-time, and with minimal geographical restrictions. As method and theory advance, a similar possibility exists for addiction science. A scientific understanding of the mechanisms associated with TBIs will be integral to fully optimize future interventions targeting SUDs.

Highlights.

Technology-based interventions (TBIs) for substance use disorders have been increasing steadily.

The mechanisms by which TBIs produce change in substance use outcomes have not been reviewed.

This article is the first review of the conceptual and empirical underpinnings of the mechanisms associated with TBIs for substance use disorders.

We discuss unique challenges and opportunities afforded by technology that can advance theory, method, and clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

Preparation of this paper was supported in part by Grants P30DA029926 (PI: L. Marsch) and R01DA023469 (PI: J. Dallery) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Some researchers argue that this requirement may not be necessary. It is possible to have mediated effect even if independent variable (X) and outcome (Y) is not significantly associated. In this case, X would affect Y though an indirect path (Hayes, 2009, MacKinnon, 2008).

Due to the asymmetric distribution of the product term, resampling strategies such as bootstrapping for significance testing and confidence interval estimation is often recommended (MacKinnon, 2008).

Contributors

Jesse Dallery developed the overall structure of the manuscript and incorporated content written by Lisa Marsch that appeared primarily in the introduction, and by Brantley Jarvis that appeared primarily in the method and in the results of TBIs associated with alcohol use. Brantley Jarvis conducted the literature search and developed Table 1, in consultation with Jesse Dallery. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest in relationship to this paper.

Contributor Information

Jesse Dallery, Department of Psychology, University of Florida.

Brantley Jarvis, Department of Psychology, University of Florida.

Lisa Marsch, Center for Technology and Health, Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, Hanover, New Hampshire.

Haiyi Xie, Center for Technology and Health, Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, Hanover, New Hampshire.

REFERENCES

- Alessi SM, Petry NM. A randomized study of cellphone technology to reinforce alcohol abstinence in the natural environment. Addiction. 2013;108:900–909. doi: 10.1111/add.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An LC, Schillo BA, Saul JE, Wendling AH, Klatt CM, Berg CJ, Ahulwalia JS, Kavanaugh AM, Christenson M, Luxenberg MG. Utilization of smoking cessation informational, interactive, and online community resources as predictors of abstinence: cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2008;10:e55. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson ID, Marsch LA, Acosta MC. Using findings in multimedia learning to inform technology-based health interventions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013;3:234–243. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF. Treatment for persons with substance use disorders: mediators, moderators, and the need for a new research approach. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008;17:S45–S49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Gustafson DH, Shah D. How can research keep up with eHealth? Ten strategies for increasing the timeliness and usefulness of eHealth research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16:e36. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi AN, Wurtps IC, MacKinnon DP. Evaluating mechanisms of behavior change to inform and evaluate technology-based interventions. In: Marsch L, Lord S, Dallery J, editors. Health Care and Technology: Using Science-based Innovations to Transform Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ET, Dickenson J, Falk EB, Lieberman MD. Using SMS text messaging to assess moderators of smoking reduction: Validating a new tool for ecological measurement of health behaviors. Health Psychol. 2011;30:186–194. doi: 10.1037/a0022201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer EW, Fletcher R, Fay RJ, Smelson D, Ziedonis D, Picard RW. Preliminary efforts directed toward the detection of craving of illicit substances: the iHeal project. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012;8:5–9. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0200-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendryen H, Drozd F, Kraft P. A digital smoking cessation program delivered through internet and cell phone without nicotine replacement (happy ending): randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2008;10:e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendryen H, Kraft P. Happy ending: a randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation intervention. Addiction. 2008;103:478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J, Wyszynski C, Comstock B, Heffner JL. Pilot randomized controlled trial of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013;15:1756–1764. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller DB, Borland R, Woodall WG, Hall JR, Hines JM, Burris-Woodall P, Miller C, Balmford J, Starling R, Ax B, Saba L. Randomized trials on consider this, a tailored, internet-delivered smoking prevention program for adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 2008;35:260–281. doi: 10.1177/1090198106288982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MN, Begale M, Duffecy J, Gergle D, Karr CJ, Giangrande E, Mohr DC. Harnessing context sensing to develop a mobile intervention for depression. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13:e55. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Graham JW. The effect of the timing and spacing of observations in longitudinal studies of tobacco and other drug use: temporal design considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:S85–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, MacKinnon DP, Reeve BB. Some methodological considerations in theory-based health behavior research. Health Psychol. 2013a;32:586–591. doi: 10.1037/a0029543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Trail JB, Kugler KC, Baker TB, Piper ME, Mermelstein RJ. Evaluating individual intervention components: Making decisions based on the results of a factorial screening experiment. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013b:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0239-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Vullo GC, Kennedy AP, Finger MS, Agrawal A, Bjork JM, Farrer LA, Hancock DB, Hussong A, Wakim P, Huggins W, Hendershot T, et al. Data compatibility in the addiction sciences: an examination of measure commonality. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;141:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Cassidy RN, Raiff BR. Single-case experimental designs to evaluate novel technology-based health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15:e22. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Glenn IM, Raiff BR. An Internet-based abstinence reinforcement treatment for cigarette smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Kurti AK, Erb JP. A new frontier: integrating and digital technology to promote health behavior. Behav. Anal. doi: 10.1007/s40614-014-0017-y. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Optimizing health interventions with single-case designs: from development to dissemination. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0258-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR, Grabinski MJ. Internet-based contingency management to promote smoking cessation: a randomized controlled study. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2013;46:750–764. doi: 10.1002/jaba.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Riley WT, Nahum-Shani I. Research designs to develop and evaluate technology-based health behavior interventions. In: Marsch L, Lord S, Dallery J, editors. Health Care and Technology: Using Science-based Innovations to Transform Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Danaher BG, Smolkowski K, Seeley JR, Severson HH. Mediators of a successful web-based smokeless tobacco cessation program. Addiction. 2008;103:1706–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devito Dabbs A, Song MK, Hawkins R, Aubrecht J, Kovach K, Terhorst L, Connolly M, McNulty M, Callan J. An intervention fidelity framework for technology-based interventions. Nurs. Res. 2011;60:340–347. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31822cc87d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra A. Working mechanisms of computer-tailored health education: evidence from smoking cessation. Health Educ. Res. 2005;20:527–539. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, McKinley LL, Book P. Evaluation of two Web-based alcohol interventions for mandated college students. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, Mackinnon DP, Taborga MP, Taylor AB. R2 effect-size measures for mediation analysis. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009;41:486–498. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.2.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW. Enhancing substance abuse treatment evaluations: examining mediators and moderators of treatment effects. J. Subst. Abuse. 1995;7:135–150. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambelunghe C, Rossi R, Aroni K, Bacci M, Lazzarini A, De Giovanni N, Carletti P, Fucci N. Sweat testing to monitor drug exposure. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2013;43:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, Levy MS, Driscoll H, Chosholm SM, Dillenburg L, Isham A, Shah D. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:566–572. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Metrik J, Kahler CW, Shiffman S. Self-efficacy and smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009;23:56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter BD, Godley SH, Hesson-McInnis MS, Roozen HG. Longitudinal change mechanisms for substance use and illegal activity for adolescents in treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014;28:507–515. doi: 10.1037/a0034199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japuntich SJ, Zehner ME, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Valdez JA, Fiore MC, Baker TB, Gustafson DH. Smoking cessation via the internet: a randomized clinical trial of an internet intervention as adjuvant treatment in a smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2006;8:S59–S67. doi: 10.1080/14622200601047900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM, Stone AA. Bringing the laboratory and clinic to the community: mobile technologies for health promotion and disease prevention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013;64:471–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007;3:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: methodological issues and research recommendations. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2003;44:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA, Kinkenberg WD, Winter JP, Trusty ML. Evaluation of treatment programs for persons with severe mental illness: moderator and mediator effects. Eval. Rev. 2004;28:294–324. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04264701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Carroll KM. New developments in treatments for substance use disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0420-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, Babuscio T, Carroll KM. Quality versus quantity: acquisition of coping skills following computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2010;105:2120–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbis A, Armeli S, Muench F, Morgenstern J. Motivation and self-efficacy in the context of moderated drinking: global self-report and ecological momentary assessment. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013;27:934–943. doi: 10.1037/a0031194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane ND, Mohammod M, Lin M, Yang X, Lu H, Ali S, Campbell A. Be well: A smartphone application to monitor, model and promote wellbeing. Paper presented at the 5th International ICST Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare; Dublin, Ireland. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KR, Voronovich ZA, Cook PF, Pedro LW. Addicted to constructs: science in reverse? Addiction. 2013;108:1532–1533. doi: 10.1111/add.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Coping skills training and contingency management treatments for marijuana dependence: exploring mechanisms of behavior change. Addiction. 2008;103:638–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvin EB, Abrantes AM, Brown RA. Computer and mobile technology-based interventions for substance use disorders: an organizing framework. Addict. Behav. 2013;38:1747–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R. The search for mechanisms of change in treatments for alcohol use disorders: a commentary. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:21s–32s. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Magill M. Recent advances in addiction treatments: focusing on mechanisms of change. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:382–389. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction To Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, Longabaugh R. The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of MI's key causal model. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0036833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Longabaugh R. Efficacy combined with specified ingredients: a new direction for empirically supported addiction treatment. Addiction. 2013;108:874–881. doi: 10.1111/add.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Dallery J. Advances in the psychosocial treatment of addiction: the role of technology in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2012;35:481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Guarino H, Acosta M, Aponte-Melendez Y, Cleland C, Grabinski M, Brady R, Edwards J. Web-based treatment for substance use disorders as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2014;46:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Lawrence DL, Jorenby DE, Shiffman S, Baker TB. Psychological mediators of bupropion sustained-release treatment for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2008;103:1521–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Theory-based processes that promote the remission of substance use disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007;27:537–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, McKay JR. Rethinking the paradigms that inform treatment research for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102:1377–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Naqvi NH, Debellis R, Breiter HC. The contributions of cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging to understanding mechanisms of behavior change in addiction. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013;27:336–350. doi: 10.1037/a0032435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi NH, Bechara A. The insula and drug addiction: an interoceptive view of pleasure, urges, and decision-making. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010;214:435–450. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0268-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T. Internet-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st-birthday drinking: A randomized controlled trial of an event-specific prevention intervention. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009;77:51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0014386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: a two-year randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Larimer ME. Being controlled by normative influences: self-determination as a moderator of a normative feedback alcohol intervention. Health Psychol. 2006;25:571–579. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Conceptual and design essentials for evaluating mechanisms of change. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:4s–12s. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Parzynski C, Mercincavage M, Conklin CA, Fonte CA. Is self-efficacy for smoking abstinence a cause of, or a reflection on, smoking behavior change? Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:56–62. doi: 10.1037/a0025482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ. Advances in mediation analysis: a survey and synthesis of new developments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015;66:825–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods. 2011;16:93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulverman R, Yellowlees PM. Smart devices and a future of hybrid tobacco cessation programs. Telemed. J. E. Health. 2014;20:241–245. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin BA, Purcell P, Naveed S, Moser RP, Henton MD, Proctor EK, Brownson RC, Glasgow RE. Advancing the application, quality and harmonization of implementation science measures. Implement. Sci. 2012;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Graham AL, Cobb N, Xiao H, Mushro A, Abrams D, Vallone D. Engagement promotes abstinence in a web-based cessation intervention: cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15:e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley WT, Glasgow RE, Etheredge L, Abernathy AP. Rapid, responsive, relevant (R3) research: a call for a rapid learning health research enterprise. Clin. Transl. Med. 2013;2:10. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, Nilsen W, Allison SM, Mermelstein R. Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task? Transl. Behav. Med. 2011;1:53–71. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan PJ, Cofta-Woerpel L, Mazas CA, Vidrine JI, Reitzel LR, Cinciripini PM, Wetter DW. Evaluating reactivity to ecological momentary assessment during smoking cessation. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:382–389. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiyko M, Naab P, Shiffman S, Li R. Modeling complexity of EMA data: time-varying lagged effects of negative affect on smoking urges for subgroups of nicotine addiction. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16:S144–S150. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Establishing a causal chain: why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005:845–851. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P, Shaw H. Testing mediators hypothesized to account for the effects of a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program over longer term follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79:398–405. doi: 10.1037/a0023321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Moderators and mediators of a web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program among nicotine patch users. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2006;8:S95–S101. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F-T, Kuo C, Cheng H-T, Buthpitiya S, Collins P, Griss M. Activity-aware mental stress detection using physiological sensors. In: Grist M, Yang G, editors. Mobile Computing, Applications, and Services. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, Dierker L. A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychol. Methods. 2012;17:61–77. doi: 10.1037/a0025814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topol EJ. The Creative Destruction Of Medicine: How The Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care. New York: Basic Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Voogt C, Kuntsche E, Kleinjan M, Poelen E, Engels R. Using ecological momentary assessment to test the effectiveness of a web-based brief alcohol intervention over time among heavy-drinking students: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014a;16:e5. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voogt CV, Kuntsche E, Kleinjan M, Engels RC. The effect of the 'What Do You Drink' web-based brief alcohol intervention on self-efficacy to better understand changes in alcohol use over time: randomized controlled trial using ecological momentary assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014b;138:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prev. Sci. 2007;8:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangberg SC, Nilsen O, Antypas K, Gram IT. Effect of tailoring in an internet-based intervention for smoking cessation: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13:e121. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Herman-Stahl M, Calvin SL, Pemberton M, Bradshaw M. Mediating mechanisms of a military Web-based alcohol intervention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winett RA, Davy BM, Savla J, Marinik EL, Winett SG, Baugh ME, Flack KD. Using response variation to develop more effective, personalized medicine?: Evidence from the Resist Diabetes study. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0263-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Why and how do substance abuse treatments work? Investigating mediated change. Addiction. 2008;103:649–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]