Abstract

Background

Concurrent sexual partnerships (partnerships that overlap in time) increase the spread of infection through a network. Different patterns of concurrent partnerships may be associated with varying STI risk depending on the partnership type (primary vs. non-primary) and the likelihood of condom use with each concurrent partner. We sought to evaluate co-parenting concurrency, overlapping partnerships in which at least one concurrent partner is a co-parent with the respondent, which may promote the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Methods

We examined sexual partnership dates and fertility history of 4928 male respondents in the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. We calculated co-parenting concurrency prevalence and examined correlates using Poisson regression.

Results

Among men with ≥1 pair of concurrent partnerships, 18% involved a co-parent. 33% of black men involved in co-parenting concurrency were < 25 years, compared to 23% of Hispanics and 6% of whites. Young black men (age 15–24) were more likely to engage in co-parenting concurrency than white men, adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics, sexual and other high-risk behaviors, and relationship quality. Compared to white men age 15–24, black and Hispanic men were 4.60 (95% CI 1.10, 19.25) and 3.45 (95% CI 0.64, 18.43) times as likely to engage in co-parenting concurrency.

Conclusion

Almost one in five men engaging in concurrent sexual partnerships in the past year was a co-parent with at least one of the concurrent partners. Understanding the context in which different types of concurrency occur will provide a foundation on which to develop interventions to prevent STIs.

Keywords: Concurrency, Co-parenting, Sexually Transmitted Infections, Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Background

Concurrent sexual partnerships (relationships that overlap in time), have been associated with the transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STI) including syphilis [1], chlamydial infection [2], and heterosexually acquired HIV infection [3]. While the rate of partner acquisition may be similar in concurrent compared to serially monogamous partnerships, the overlap of sexual partnerships can lead to faster spread and establishment of STIs in a population [3–6].

Research concerning the socio-cultural factors that influence the occurrence of concurrency has begun to emerge for some populations, such as the relationship between acculturation and sexual behavior among Hispanic youth [3, 7, 8]. In addition, qualitative research has identified different concurrency patterns that may be associated with varying STI risk depending on partnership type (primary vs. non-primary) and the likelihood of condom use with each concurrent partner [9]. One pattern potentially associated with high STI risk involves concurrency in the context of a co-parenting relationship [9]. Co-parenting concurrency involves engaging in sexual intercourse with a co-parent while in another sexual partnership. Black, unmarried fathers report difficulty with ending a sexual relationship with the mother of their children despite not being in a mutually monogamous relationship with her. Furthermore, women in main partnerships with unmarried fathers reported sexual activity outside the relationship as more acceptable if it occurs with a co-parent [9, 10].

To date, no published study has quantitatively examined co-parenting in the context of concurrent sexual partnerships. We used data from male respondents in Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) to: (1) calculate the overall and race-specific- prevalence of co-parenting concurrency; (2) describe co-parenting concurrency patterns, and (3) determine demographic and behavioral correlates of co-parenting concurrency.

Methods

The NSFG is a cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics designed to examine trends in contraception, marriage, divorce, sexual activity and fertility[11]. Cycle 6 of the NSFG was conducted in 2002 and was the first cycle to include men. Men and women aged 15–44 years in the US household population were targeted, and teens (aged 15–19), African Americans, and Hispanics were oversampled [12]. The survey collected data about demographic, socio-economic, and behavioral characteristics and was administered by female interviewers using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). More sensitive questions were administered using audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) [12]. Seventy-eight percent of males sampled completed the interview, yielding a total of 4928 male respondents [12]. We excluded 274 men who reported a race/ethnicity other than white, non-Hispanic black or Hispanic from all analyses because only 12 men in this group engaged in concurrency resulting in a final sample of 4654 men.

Concurrent Sexual Partnerships

Concurrency with female partners was determined, as in previous research [3, 13–15], by examining dates of first and last intercourse with each partner discussed during the interview. Reported dates of first sexual intercourse for up to four (current wife/partner and three most recent) sexual partners were ordered sequentially. Partnerships that ended 12 months before the interview were excluded. The dates of first and last sex for all partnerships were compared for men who provided information on two or more sexual partners.

For each partnership pair, the month of first sexual intercourse with the later partner was compared with the month of last sexual intercourse with the earlier partner. If the month of first sex with the later partner occurred before the month of last sex with the earlier partner, the partnership was considered concurrent. Co-parents were defined as a man and woman who are the joint biological parents of a child. For each sexual partner, a respondent was asked questions about children he co-parented with the partner, including biological, foster, adopted, and step children. Only biological children were included in our co-parenting definition, and biological children from other partnerships that ended more than 12 months before the interview were not included. A concurrent partnership pair was classified as co-parenting concurrency if the respondent had a biological child with at least one of the concurrent sexual partners.

Additional Measures

A conceptual model for the association between co-parenting and concurrency was used to identify potential correlates of co-parenting concurrency. Socio-demographic characteristics included age, race, educational attainment, and household income as a percent of the 2000 US poverty line. Sexual behaviors that affect the risk of STIs included the respondent’s number of sexual partners (lifetime and in the past 12 months), frequency of condom use, and age at first sexual intercourse. Each respondent was asked about relationship characteristics, sexual activity, and fertility in relation to his reported sexual partners. We categorized incarceration for at least 24 hours as never, within the past 12 months and greater than 12 months ago. Cohabitation status at the time of the child’s birth and average relationship duration were used as proxy measurements for relationship quality.

Analysis

All variables were coded as dichotomous or nominal categorical variables. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX) and incorporated the NCHS-provided sample weights and sampling design variables [12]. We examined demographic, socio-economic, fertility, and sexual behavior characteristics among all male respondents (N=4654), all fathers (N=1653), and all men with overlapping partnerships with women in the past 12 months (N=430). We calculated the prevalence of co-parenting concurrency, with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) overall and by racial/ethnic group. We calculated chi-square statistics for bivariable associations of co-parenting concurrency with socio-demographic and behavioral and relationship characteristics. Effect measure modification by race/ethnicity and age was examined using a product interaction model and a Wald test at the p<0.20 significance level. Prevalence ratios and 95% CIs were calculated using a multivariable Poisson regression model including all covariates of interest and a race by age interaction term.

Results

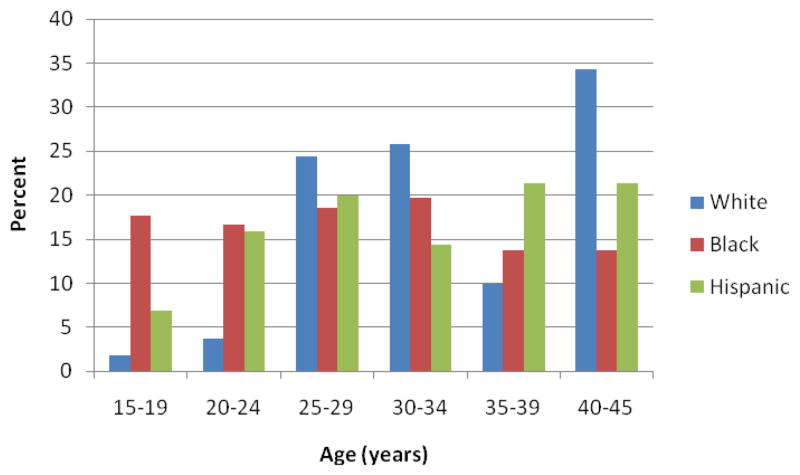

Differences between men engaging in concurrent partnerships and the entire NSFG sample have been described in detail in previous analyses [3]. Approximately 18.0% of concurrent sexual partnerships among US men involved a co-parent, and the overall prevalence varied slightly by race/ethnicity (Table 1). Black and Hispanic men who engaged in co-parenting concurrency were considerably younger than white men who engaged in co-parenting concurrency. Slightly more than a third of black men involved in co-parenting concurrency were younger than 25 years, compared to 23% of Hispanic men and only 6% of white men (Figure 1). The Wald p-value for the interaction between race/ethnicity was 0.06 indicating PR modification by race/ethnicity and age.

TABLE 1.

Co-parenting Concurrency Prevalence among US Men Reporting Concurrency in the Past 12 Months (N=430), 2002 National Survey of Family Growth

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Co-Parenting Concurrency | ||

| Unweighted N | Weighted %* | |

| Overall | 59 | 18.0 |

| Age at Interview (Years) | ||

| 15–19 | 7 | 7.6 |

| 20–24 | 10 | 5.8 |

| 25–29 | 12 | 25.6 |

| 30–34 | 12 | 22.6 |

| 35–39 | 11 | 19.7 |

| 40–45 | 7 | 29.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 13 | 14.7 |

| Black | 30 | 17.8 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 18.2 |

| Education§ | ||

| < High School | 17 | 47.1 |

| High School/GED | 18 | 16.9 |

| Some College | 10 | 13.4 |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 4 | 5.3 |

| Household income as a percent of 2000 poverty line§ | ||

| <150% | 22 | 39.7 |

| 150%–249% | 5 | 28.7 |

| 250–399% | 12 | 17.4 |

| ≥400% | 10 | 8.4 |

| Current Marital Status | ||

| Married | 18 | 76.9 |

| Cohabiting | 9 | 36.7 |

| Previously Married† | 8 | 7.1 |

| Never Married | 24 | 6.9 |

| Number of Biological Children# | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 28 | 42.6 |

| 2 | 12 | 44.1 |

| 3 | 13 | 72.1 |

| ≥4 | 6 | 61.6 |

| Number of Children Born Outside Marriage#‡ | ||

| 0 | 13 | 41.9 |

| 1 | 27 | 55.1 |

| 2 | 11 | 59.6 |

| ≥3 | 8 | 56.6 |

| Cohabitation at Child’s Birth‡ | ||

| Non-Cohabiting Only | 16 | 35.2 |

| Cohabiting Only | 31 | 51.5 |

| Both Cohabiting and non-Cohabiting | 12 | 70.5 |

| Multiple Partner Fertilityठ| ||

| No | 41 | 12.5 |

| Yes | 18 | 51.8 |

| Age at First Sexual Intercourse (Years) | ||

| ≥18 | 10 | 25.2 |

| 16–17 | 8 | 8.2 |

| 14–15 | 22 | 36.4 |

| ≤13 | 19 | 19.5 |

| Number of Lifetime Sexual Partners | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3–5 | 9 | 12.6 |

| 6–10 | 14 | 10.9 |

| ≥11 | 36 | 15.0 |

| Number of Sexual Partners in the Past 12 Months | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 29 | 28.9 |

| 3 | 19 | 13.1 |

| ≥4 | 11 | 4.8 |

| Condom Use During the Last Month | ||

| None of the time | 21 | 23.4 |

| Some of the time | 13 | 24.6 |

| All of the time | 18 | 7.3 |

| Incarceration for ≥24 hours | ||

| Never | 38 | 18.9 |

| >12 months ago | 14 | 11.8 |

| Within past 12 months | 7 | 14.3 |

Weighted to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal selection probabilities yielding nationally representative estimates. Percents may not sum to zero due to rounding.

Among men aged 22 years and older (n=309)

Includes separated, divorced, and widowed

Includes children fathered with the respondent’s current wife/cohabiting partner or 3 most recent partners in the 12 months prior to the interview

Among men who have a biological child (n=136)

Includes children fathered with the respondent’s current wife/cohabiting partner, 3 most recent partners in the 12 months prior to the interview, former wives, first premarital cohabiting partner, or other biological children fathered with women who were not discussed in other sections of the interview

FIGURE 1.

Age Distribution of Co-parenting Concurrency by and Race/Ethnicity ^

^N=430 white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic men reporting concurrency in the past 12 months

In a previous analysis of these data, it was estimated that 11% of the men had concurrent partnerships [3]. Among this subset of 430 men, the prevalence of co-parenting concurrency was highest among men with less than a high school education and decreased with increasing education (Table 1). The prevalence of co-parenting concurrency among men with the lowest household incomes was almost five times the prevalence among men with the highest household incomes (39.7% vs. 8.4%). Co-parenting concurrency prevalence was slightly higher among men who had children born outside marriage compared to men who did not but did not vary depending on the number of children born outside marriage (Table 1). Co-parenting concurrency was more prevalent among fathers who had children with multiple partners (51.8%) than among fathers who did not have multiple partner fertility (12.5%).

Based on unadjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and Wald tests (Table 2), age at interview, education, household income, condom use during the last month, cohabitation at the time of the child’s birth, and average relationship duration were associated with co-parenting concurrency. Among men who engaged in concurrent partnerships, those with an average relationship duration of 3–5 years were 5 times as likely to be involved in co-parenting concurrency [PR 5.23 (1.98, 18.83)] as those whose average relationship lasted less than 1 year. The association was even stronger for average relationship duration of 6 years or more compared to less than 1 year [PR 13.79 (5.58, 34.10)].

TABLE 2.

Correlates of Co-parenting Concurrency among Men Who Had Concurrent Partnerships in the Past 12 Months^

| Co-parenting Concurrency in the past 12 months

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| N | % | N | % | Bivariable Model PR (95% CI) |

Wald p-value | Multivariable Model PR (95% CI) |

|||

| Total | 59 | 16.3 | 371 | 83.7 | |||||

| Age at Interview (Years) | |||||||||

| 15–24 | 17 | 18.0 | 176 | 50.9 | 0.26 | (0.11, 0.57) | 0.0002 | 3.51 | (1.86 6.62) |

| 25–34 | 24 | 43.1 | 98 | 26.6 | 0.95 | (0.41, 2.21) | 1.60 | (0.84 3.03) | |

| ≥35 | 18 | 39.0 | 97 | 22.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Education | |||||||||

| < High School | 22 | 47.7 | 78 | 19.9 | 1.0 | 0.01 | 1.0 | ||

| High School/GED | 20 | 24.2 | 120 | 30.0 | 0.43 | (0.20, 0.93) | 0.74 | (0.45 1.23) | |

| Some College | 13 | 23.7 | 115 | 35.2 | 0.56 | (0.28, 1.15) | 0.81 | (0.41 1.62) | |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 4 | 4.4 | 58 | 15.4 | 0.16 | (0.04, 0.58) | 0.27 | (0.12 0.58) | |

| Household income as a percent of 2000 poverty line | |||||||||

| <150 | 25 | 38.7 | 70 | 17.4 | 4.00 | (1.97, 8.14) | 0.007 | 2.36 | (1.30 4.28) |

| 150–249 | 7 | 21.7 | 72 | 17.2 | 2.14 | (0.58, 7.81) | 0.90 | (0.49 1.64) | |

| 250–399 | 14 | 18.1 | 76 | 22.7 | 1.43 | (0.50, 4.05) | 2.14 | (1.20 3.83) | |

| ≥400 | 13 | 25.6 | 153 | 42.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Age at First Sexual Intercourse (Years) | |||||||||

| ≥18 | 10 | 26.4 | 47 | 15.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | ||

| 16–17 | 8 | 13.9 | 104 | 29.1 | 0.37 | (0.10, 1.32) | 0.66 | (0.31 1.39) | |

| 14–15 | 22 | 36.4 | 148 | 36.9 | 0.83 | (0.32, 2.20) | 0.49 | (0.28 0.86) | |

| <14 | 19 | 23.3 | 72 | 18.8 | 0.78 | (0.27, 2.24) | 0.59 | (0.28 1.24) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 13 | 47.5 | 152 | 53.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | ||

| Black | 30 | 29.1 | 136 | 26.2 | 1.21 | (0.52, 2.80) | 1.21 | (0.65 2.23) | |

| Hispanic | 16 | 23.4 | 83 | 20.5 | 1.23 | (0.49, 3.09) | 1.22 | (0.74 2.02) | |

| Condom Use During the Last Month | |||||||||

| None of the time | 21 | 60.1 | 101 | 39.0 | 2.50 | (1.14, 5.48) | 0.002 | 1.88 | (1.13 3.12) |

| Some of the time | 13 | 20.9 | 41 | 12.7 | 2.59 | (1.14, 5.87) | 1.65 | (0.90 3.02) | |

| All of the time | 18 | 19.0 | 166 | 48.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Cohabitation at Child’s Birth * | |||||||||

| Non-Cohabiting Only | 16 | 19.2 | 28 | 38.7 | 0.62 | (0.34, 1.12) | 0.07 | 0.86 | (0.46 1.59) |

| Cohabiting Only | 31 | 42.7 | 34 | 43.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Both Cohabiting and non-Cohabiting | 12 | 38.1 | 15 | 17.4 | 1.29 | (0.85, 1.98) | 0.89 | (0.55 1.45) | |

| Average Relationship Duration | |||||||||

| <1 year | 7 | 8.3 | 141 | 36.4 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.0 | ||

| 1–2 years | 8 | 12.4 | 109 | 27.3 | 1.96 | (0.52, 7.39) | 0.67 | (0.31 1.45) | |

| 3–5 years | 20 | 28.5 | 89 | 27.8 | 5.23 | (1.98, 13.84) | 1.85 | (0.95 3.60) | |

| ≥6 years | 24 | 50.9 | 32 | 8.4 | 13.79 | (5.58, 34.10) | 3.43 | (1.86 6.31) | |

| Incarceration for ≥24 hours | |||||||||

| Never | 38 | 65.8 | 209 | 54.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | |||

| >12 months ago | 14 | 18.2 | 99 | 26.5 | 1.07 | (0.54, 2.09) | 0.60 | (0.35 1.03) | |

| Within past 12 months | 7 | 16.1 | 63 | 18.7 | 0.75 | (0.27, 2.06) | 0.54 | (0.34 0.85) | |

N=430 men reporting concurrency in the past 12 months

Among men who have a biological child (n=139)

The associations of co-parenting concurrency with poverty, condom use, average relationship duration, and incarceration history persisted in the final, multivariable model (Table 2). Lower household income and increased relationship duration were associated with an increased likelihood of co-parenting concurrency, with PRs increasing as household income decreased. Men who never used a condom were more likely to have engaged in co-parenting concurrency in the past 12 months compared to men who always used a condom [PR 1.88 (1.13, 3.12)]. Having a history of incarceration, particularly incarceration within the past 12 months, was associated with a decreased likelihood of co-parenting concurrency [PR 0.54 (0.34, 0.85)].

Young black men (age 15–24) were more likely to engage in co-parenting concurrency than white men, adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics, sexual and other high-risk behaviors, and relationship quality (Table 3). The largest racial differences in co-parenting concurrency prevalence were observed among men age 15–24. Compared to white men age 15–24, black and Hispanic men were 4.60 (95% CI 1.10, 19.25) and 3.45 (95% CI 0.64, 18.43) times as likely to engage in co-parenting concurrency. White men age ≥35 were slightly more likely than black and Hispanic men to engage in co-parenting concurrency.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted Prevalence Ratios (PR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for Co-Parenting Concurrency by Age and Race/Ethnicity, 2002 National Survey of Family Growth *

| Co-Parenting Concurrency | Prevalence | PR | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Interview (Years) | No | Yes | Total | weighted % | ||

| 15–24 | ||||||

| White | 76 | 3 | 79 | 1.8 | 1.0 | |

| Black | 55 | 9 | 64 | 14.3 | 4.60 | (1.10, 19.25) |

| Hispanic | 45 | 5 | 50 | 8.5 | 3.45 | (0.64, 18.43) |

| 25–34 | ||||||

| White | 30 | 6 | 36 | 28.9 | 1.0 | |

| Black | 40 | 13 | 53 | 22.1 | 0.99 | (0.37, 2.65) |

| Hispanic | 28 | 5 | 33 | 17.2 | 1.83 | (0.69, 4.87) |

| ≥35 | ||||||

| White | 46 | 4 | 50 | 22.2 | 1.0 | |

| Black | 41 | 8 | 49 | 18.3 | 0.86 | (0.36, 2.10) |

| Hispanic | 10 | 6 | 16 | 53.0 | 0.90 | (0.49, 1.66) |

Estimates calculated using multivariable Poisson regression for survey data adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics (age, education, household income as a % of the 2000 US poverty line), sexual behaviors (age at first sexual intercourse, condom use), relationship quality (average relationship duration, cohabitation at the time of the child’s birth), and other high-risk behaviors (incarceration history); N=430 men who engaged in concurrent sexual partnerships in the past 12 months

Discussion

This study is the first to explore quantitatively the role of co-parenting relationships in concurrent sexual partnerships. Almost one in five men engaging in concurrent sexual partnerships with women in the past 12 months had a biological child with at least one of his concurrent partners. Research among US men estimated concurrency was three and two times as likely among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, respectively, compared to non-Hispanic whites [14]. Data from our analyses do not suggest racial/ethnic differences in the overall prevalence of co-parenting among men engaging in concurrency, though co-parenting concurrency did vary considerably when examined jointly by race/ethnicity and age. The largest racial/ethnic disparities in co-parenting concurrency prevalence were observed among men aged 15–24 with blacks and Hispanics being four to five times as likely to engage in co-parenting concurrency as their white counterparts.

Results from this analysis highlight a potential population for which STI/HIV prevention messages could be developed. Young people (age 15–24), including young parents, have been found to engage in a variety of risk behaviors, such as having multiple and concurrent sexual partners, unprotected intercourse, drug or alcohol use, and needle sharing [16–18]. Inconsistent condom use was almost four times as likely among adolescent couples with a child compared to those without a child [19]. Furthermore, young parents in relationships were generally unaware of their intimate partner’s HIV testing history [20].

Co-parenting is generally discussed in the context of married couples, though it can occur in a number of different scenarios [21]. Approximately 40% of all births in the US in 2007 were to unmarried women, and the proportion of births to unmarried non-Hispanic black women (71.6%) was approximately 2.5 times as high as the proportion of births to non-Hispanic white women (27.8%) [22]. Relationships between unmarried parents are often unstable and characterized by repeated break-ups and reunions, [23, 24] creating an environment conducive to concurrency. In our analyses, births outside marriage were reported by over three quarters (76.3%) of men engaging in co-parenting concurrent partnerships, supporting the idea of increased concurrency among unmarried parents.

The term nonresident father includes a wide variety of men (e.g. divorced men who may or may not be remarried) but has more recently been used in research targeting non-resident fathers, regardless of marital status [25–27]. Nonresident fathers’ involvement with their children differs by race/ethnicity, and this difference can be partially explained by the status of the mother-father relationship [25]. Specifically, minority nonresident fathers were more likely to maintain romantic relationships with their child’s mother than white fathers, while mothers who had children with white men were more likely to re-partner [25]. Thus, it is possible that the co-parenting relationship, particularly among unmarried racial/ethnic minorities, could impact the formation and persistence of concurrent sexual partnerships.

The trend toward co-parenting concurrency’s increased prevalence among white men age 35 and older compared to black and Hispanic men of the same age further highlights the importance of considering social contexts surrounding concurrent partnerships. Racial/ethnic differences in marriage and cohabitation may explain some of the observed differences in co-parenting concurrency. Blacks in the US are less likely than other racial/ethnic groups to marry[28], and among both men and women, unmarried individuals are much more likely to engage in concurrent partnerships than married individuals [13, 28]. Thus, one possible explanation is that co-parenting concurrency’s occurrence among young black and Hispanic men results from continued sexual activity with the co-parent after initiation of a new, perhaps main, relationship. Conversely, among older white men, co-parenting concurrency could be occurring in the context of an extramarital affair.

The cross-sectional nature of the data prohibited us from drawing causal inferences and must be acknowledged as a limitation. We were also not able to examine the contexts surrounding transitions into and out of sexual partnerships. Information on partnerships and children conceived in them was available for at most four sexual partners and only partnerships active during the past year. Men who had other partners could have had concurrent partnerships and children that were undetected. Additionally, sexual partnership dates were reported by month and year which could have introduced some ambiguity in determining concurrency status. For example, a sexual partnership that appeared to span two years could actually have consisted of one sexual act with a woman during one month and a second sexual act with the same woman two years later. Finally, the limited number of outcomes and a significant age by race/ethnicity interaction resulted in small cell counts which decreased the precision of our effect estimates.

We defined co-parents as a man and woman who are the joint biological parents of a child. This definition was more restrictive than that proposed in the sociology and child development literature, which includes co-parents regardless of their sexual orientation or biological linkage to the child [21]. Though some instances of co-parenting could have been missed by our more specific definition, the significance of a biological child as a continuing manifestation of earlier sexual intimacy argues for differentiating adoptive and biological children in examining co-parenting concurrency.

Accuracy of self-report in this study depends on both recall and willingness to disclose sensitive information. The NSFG 2002 utilizes a life calendar approach to assist respondents in recalling information, but the potential for misreporting partnerships and/or dates remains. Self-report of sexual behaviors varies depending on the mode in which the survey is administered [29], and the use of ACASI likely improved the completeness of self reported sensitive and high-risk behaviors [30–32]. We have no evidence that reporting of sexual behaviors differed according to concurrency status.

Although the contextual factors that promote concurrency are not yet clear, they are likely to include a combination of imbalanced sex ratios, low marriage rates, economic differentials, media influences, and community and cultural norms. Our results show that the prevalence of co-parenting concurrency differs by race/ethnicity and age and that this concurrency pattern is most prevalent among young black and Hispanic men. A comprehensive understanding of the types of concurrent sexual partnerships and the contexts in which they occur should provide a basis for more effective prevention interventions and public messages.

Co-parenting relationships are complex and have profound implications for child health and development. Concurrent sexual partnerships add an additional layer of complexity to co-parenting relationships, which can affect the health of the co-parents, their other partners, and their community. Thus, future research should examine whether there is a link between co-parenting concurrency and STI transmission. The concept of co-parenting concurrency could be incorporated into STI studies by including questions on fertility histories and dates of sexual intercourse into data collection instruments. The importance of co-parenting relationships in sexual networks warrants further investigation and could be beneficial in determining the role these relationships play in population-level STI dissemination.

Summary.

A study of US men found that almost one in five men engaging in concurrent partnerships was a co-parent with at least one concurrent partner, and co-parenting concurrency was most common among young black men.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support

Support was provided by NIH/NIAID 5T32AI007001-33: Training in Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS, NIH 1K24HD059358, NIH 1R21HD054293.

References

- 1.Koumans EH, Farley TA, Gibson JJ, et al. Characteristics of persons with syphilis in areas of persisting syphilis in the united states: sustained transmission associated with concurrent partnerships. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:497–503. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potterat JJ, Zimmerman-Rogers H, Muth SQ, et al. Chlamydia transmission: Concurrency, reproduction number, and the epidemic trajectory. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:1331–39. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2230–37. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kretzschmar M, Morris M. Measures of concurrency in networks and the spread of infectious disease. Math Biosci. 1996;133:165–95. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghani AC, Swinton J, Garnett GP. The role of sexual partnership networks in the epidemiology of gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:45–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts CH, May RM. The influence of concurrent partnerships on the dynamics of HIV/AIDS. Math Biosci. 1992;108:89–104. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady SS, Tschann JM, Ellen JM, et al. Infidelity, trust, and condom use among Latino youth in dating relationships. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:227–31. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181901cba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty IA, Minnis A, Auerswald CL, et al. Concurrent partnerships among adolescents in a Latino community: the mission district of San Francisco, California. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:437–43. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000251198.31056.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorbach PM, Stoner BP, Aral SO, et al. “It takes a village”: understanding concurrent sexual partnerships in Seattle, Washington. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:453–62. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey MP, Senn TE, Seward DX, et al. Urban african-american men speak out on sexual partner concurrency: findings from a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2008;14:38–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groves RM, Benson G, Mosher WD, et al. Plan and operation of cycle 6 of the national survey of family growth. Vital Health Stat 1. 2005;42:1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepkowski J, Mosher W, Davis K. National survey of family growth, cycle 6: sample design, weighting, imputation, and variance estimation. Vital Health Stat. 2006;2:1–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Bonas DM, et al. Concurrent sexual partnerships among women in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002;13:320–27. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Adimora AA. Condom use and duration of concurrent partnerships among men in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:265–72. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318191ba2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, et al. Concurrent partnerships, non-monogamous partners, and substance use among women in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010 Aug 19; doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174292. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koniak-Griffin D, Brecht ML. AIDS risk behaviors, knowledge, and attitudes among pregnant adolescents and young mothers. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:613–24. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Uman G, et al. Teen pregnancy, motherhood, and unprotected sexual activity. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26:4–19. doi: 10.1002/nur.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesser J, Tello J, Koniak-Griffin D, et al. Young latino fathers’ perceptions of paternal role and risk for HIV/AIDS. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2001;23:327–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz B, Fortenberry J, Zimet G, et al. Partner-specific relationship characteristics and condom use among young people with sexually transmitted diseases. J Sex Res. 2000;37:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koniak-Griffin D, Huang R, Lesser J, et al. Young parents’ relationship characteristics, shared sexual behaviors, perception of partner risks, and dyadic influences. J Sex Res. 2009;46:483–93. doi: 10.1080/00224490902846495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Egeren LA, Hawkins DP. Coming to terms with coparenting: implications of definition and measurement. J Adult Dev. 2004;11:165–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton B, Martin J, Ventura S. Births: Preliminary data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009:57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edin K, England P, Linnenberg K. Love and distrust among unmarried parents. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mclanahan S, Garfinkel I, Reichman N, et al. The fragile families and child wellbeing study: baseline national report. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, Princeton University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabrera N, Ryan R, Mitchell S, et al. Low-income, nonresident father involvement with their toddlers: variation by fathers’ race and ethnicity. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22:643–47. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson MJ, Mclanahan SS, Brooks-Gunn J. Coparenting and nonresident fathers’ involvement with young children after a nonmarital birth. Demography. 2008;45:461–88. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King V, Harris KM, Heard HE. Racial and ethnic diversity in nonresident father involvement. J Marriage Fam. 2004;66:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin P, Mosher W, Chandra A. Marriage and cohabitation in the united states: a statistical portrait based on cycle 6 (2002) of the national survey of family growth. Vital Health Stat. 2010;23:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:859–83. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochstim J. A critical comparison of three strategies of collecting data from households. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62:976–89. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opin Q. 1996;60:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waruru AK, Nduati R, Tylleskär T. Audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) may avert socially desirable responses about infant feeding in the context of hiv. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]