Abstract

Object

Meningioma is a disease with considerable morbidity and is more commonly diagnosed in females than in males. Hormonally related risk factors have long been postulated to be associated with meningioma risk, but no examination of these factors has been undertaken in males.

Methods

Subjects were male patients with intracranial meningioma (n = 456), ranging in age from 20 to 79 years, who were diagnosed among residents of the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina, the San Francisco Bay Area, and 8 counties in Texas and matched controls (n = 452). Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between hormonal factors and meningioma risk in men.

Results

Use of soy and tofu products was inversely associated with meningioma risk (OR 0.50 [95% CI 0.37–0.68]). Increased body mass index (BMI) appears to be associated with an approximately 2-fold increased risk of developing meningioma in men. No other single hormone–related exposure was found to be associated with meningioma risk, although the prevalence of exposure to factors such as orchiectomy and vasectomy was very low.

Conclusions

Estrogen-like exogenous exposures, such as soy and tofu, may be associated with reduced risk of meningioma in men. Endogenous estrogen–associated factors such as high BMI may increase risk. Examination of other exposures related to these factors may lead to better understanding of mechanisms and potentially to intervention.

Intracranial meningioma accounted for 33.8% of all primary brain and CNS tumors reported in the US between 2005 and 2009 and represents the most frequently diagnosed primary brain tumor in adults.11 Males constitute only about one-third of all meningioma cases diagnosed, and the reasons for sex differences in incidence rates are not clear.11

Recent reports have shown that family history,8 allergies,18 dental x-ray exposure,7 and cigarette smoke10 may be positively or inversely associated with meningioma risk. That meningioma occurs less frequently in men than women suggests that hormones, possibly estrogen, may play a role.6 In a recent analysis of the female cases and controls in our large population-based study we did not detect associations between reproductive variables and meningioma risk overall.9 However, among premenopausal women with a higher body mass index (BMI), there was a significantly increased risk associated with oral contraceptive use, with an OR of 1.8 (95% CI 1.1–2.9). A decreased risk was associated with a history of breast feeding (OR 0.78 [95% CI 0.63–0.96]). There is some evidence from other studies that use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may be associated with an increased risk. A recent report from the Mayo Clinic by Blitshteyn et al.1 found a significant 2-fold increased risk of meningioma among those with current or past use of HRT in a large cohort of 355,818 women that included 1390 cases of meningioma. No distinction between formulations of HRT was addressed in this report. Histological evidence also supports a belief that meningioma may be influenced by estrogen or progesterone, with 70% of tumors expressing progesterone receptors and up to 30% expressing estrogen receptors.2,13 Androgen receptors have been less frequently studied, but these receptors have also been found in meningiomas and appear to be functional.3

Despite the occurrence of 28,884 newly diagnosed meningiomas in males per year in the US, very little is known about the etiology in men. To our knowledge, the role of hormone exposure specifically among men has not been studied. To explore the apparent protection for developing meningioma associated with male sex, we assessed exogenous and endogenous hormone exposure in males participating in a large population-based case-control study of meningioma

Methods

Study Design

Eligible individuals included all persons diagnosed with a histologically confirmed intracranial meningioma among residents of the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina, as well as the Alameda, San Francisco, Contra Costa, Marin, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties of California, and the Brazoria, Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Chambers, Galveston, Liberty, and Waller counties of Texas from May 1, 2006, to October 9, 2012.

Cases were identified through the Rapid Case Ascertainment systems and state cancer registries of the respective sites, and patients were between the ages of 20 and 79 years at time of diagnosis. Control individuals were selected by an outside consulting firm (Kreider) using random-digit dialing and were matched to cases by a 5-year age interval, sex, and residence. Study patients with previous meningioma and/or a brain lesion of unknown type were excluded. Patients spoke English or Spanish. The study, consent forms, and questionnaire were approved by the Human Investigation Committees at the Yale University School of Medicine; Brigham and Women’s Hospital; the University of California, San Francisco; the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center; and Duke University Medical Center in collaboration with the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry. The study was also approved by the State of Connecticut Department of Public Health Human Investigation Committee with some data directly obtained from the Connecticut Tumor Registry in the Connecticut Department of Public Health as well as the Massachusetts Tumor Registry. The current analyses are restricted to male cases and controls.

Data Collection

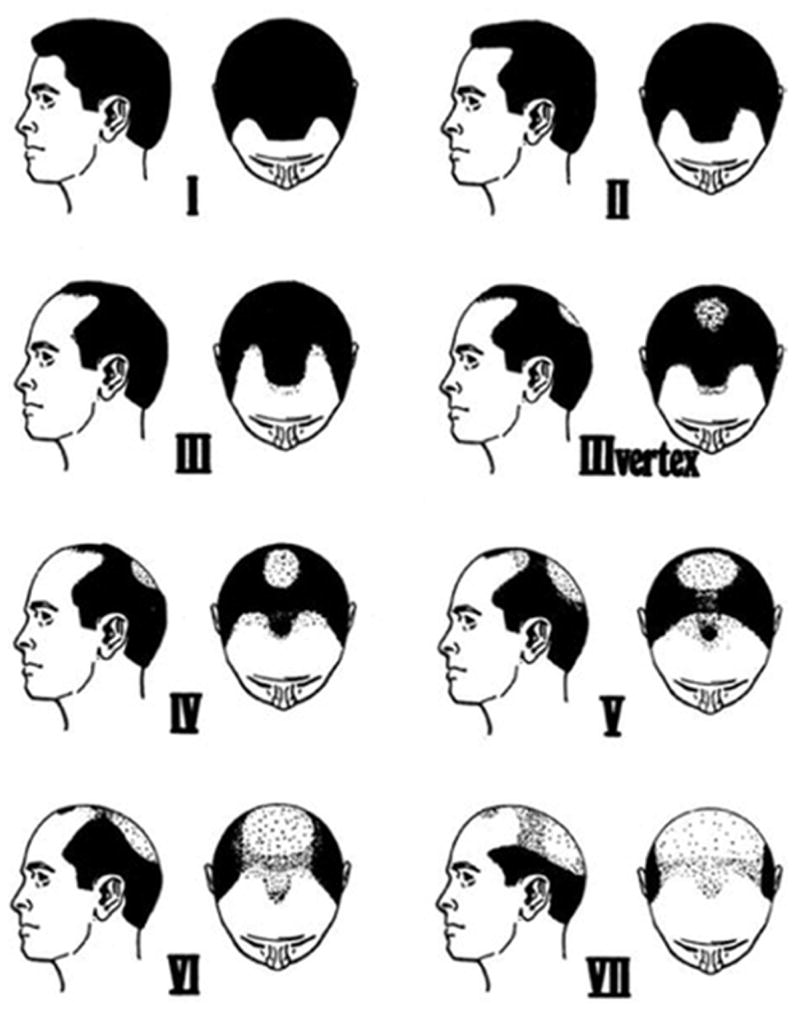

The physicians of each eligible patient were contacted to request permission to approach the individual. Patients approved for contact by their physicians and controls identified by Kreider were sent an introductory letter. Approximately 1–2 weeks later, a trained interviewer contacted the potential study individual by telephone to administer the interview. Prior to the interview, the men received the Norwood-Hamilton Scale to enable them to identify the stage of male pattern baldness at age 30 years (Fig. 1),12 if applicable. Interviews took an average of 52 minutes. Proxies provided information for 12 patients and no controls. The questionnaire included detailed questions on family history of cancer, exogenous hormone history, demographics, medical and screening history, and smoking and alcohol consumption. Risk factor and screening information were truncated at the date of diagnosis for patients and the date of interview for controls (hereafter referred to as the reference date). To date, 2674 eligible cases and 3227 eligible controls have been identified, and 98% of eligible cases had a consenting physician. Among cases, 63% participated in the interview portion of the study, whereas 50% of eligible controls participated in the interview. A total of 756 cases were ineligible due to out-of-state residency (n = 47), language (n = 82), recurrent meningioma (n = 85), incarceration (n = 3), age (n = 50), spinal meningioma (n = 154), pathological specimen unavailable for review (n = 80), mental or medical illness (for example, deafness [n = 130]), death (n = 97), another pathology (such as lung metastasis) (n = 18), or other (10). An additional 1127 cases were excluded because they were females. Among controls, 124 were ineligible due to out-of-state residency (n = 6), language (n = 8), a history of previous brain tumor of unknown pathology (n = 9), age group (n = 3), mental or medical illness (n = 79), death (n = 4), or other (n = 15). An additional 1092 controls were excluded because they were females. Ninety percent and 74% of interviewed cases and control individuals, respectively, agreed to provide a blood/saliva specimen. The sample used in this analysis included 908 eligible and enrolled male subjects (456 cases and 452 controls).

Fig. 1.

The Norwood-Hamilton Scale of Baldness Hair patterns. Frontal baldness (Types II and III), mild vertex baldness (Types IIIvertex, and IV), and severe vertex baldness (≥ Type V). From Norwood OT: Hair Transplant Surgery, 1st edition, 1973. Courtesy of Charles C Thomas Publisher Ltd., Springfield, Illinois.

Variables and Coding

Using the Norwood-Hamilton Scale,16 male pattern baldness was categorized as none (Type I), frontal baldness, mild vertex baldness (Types II, III, IIIvertex, and IV) and severe vertex baldness (Type ≥ V). Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2) and was categorized as the following: less than 25 kg/m2 (normal), 25 to less than 30 kg/m2 (overweight), 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 (obesity I), and 35 or greater kg/m2 (obesity II). Additional factors related to hormone exposure were evaluated for association with meningioma risk including “ever receive luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH)” (yes, no), “ever take antiandrogen” (yes, no), “ever use testosterone” (yes, no), “ever eat soy or tofu” (yes, no), “ever had vasectomy” (yes, no), “ever had orchiectomy” (yes, no), and “ever use hair regrowth products” (yes, no).

Statistical analysis

The initial statistical analysis included descriptive statistics. We used t-tests, chi-square analysis, and Fisher’s exact tests to examine the association between the risk of meningioma and independent covariates. To assess the odds of a meningioma being associated with individual risk factors, unconditional logistic regression was used to provide maximum likelihood estimates of the odds ratios (adjusted for age and race) with 95% confidence intervals, using the statistical package PC-SAS (version 9.2, SAS, Inc.).

Results

Demographics, Family History, and BMI

Altogether, there were 456 male cases with meningioma and 452 male controls available for this analysis. No significant difference in age at diagnosis/interview was found in cases compared with controls (p = 0.40). The mean age at diagnosis/interview was approximately 59 years in both groups (p = 0.30, data not shown). Approximately 87% of the cases and 85% of controls were white, while slightly more cases than controls were black (6.1% vs 4.7%). We found no significant case-control differences in the distribution of race and income, although the controls achieved a higher level of education than the cases (p < 0.0001). A family history of meningioma was more common among cases than controls (p = 0.002). Lifestyle differences included less alcohol consumption and a greater prevalence of smoking among cases than controls. Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for all subjects

| No. of Subjects (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Meningioma Cases (n = 456) | Controls (n = 452) | p Value |

| age at diagnosis/interview (yrs) | 0.4 | ||

| 20–29 | 10 (2.2) | 13 (2.9) | |

| 30–39 | 35 (7.7) | 33 (7.3) | |

| 40–49 | 73 (16.1) | 78 (17.3) | |

| 50–59 | 93 (20.5) | 114 (25.3) | |

| 60–69 | 147 (32.4) | 135 (29.9) | |

| ≥70 | 96 (21.2) | 78 (17.3) | |

| missing | 2 | 1 | |

| race | 0.29 | ||

| white | 397 (87.1) | 384 (85.3) | |

| black | 28 (6.1) | 21 (4.7) | |

| Asian | 14 (3.1) | 20 (4.4) | |

| other | 17 (3.7) | 25 (5.6) | |

| missing | 2 | ||

| study site | 0.14 | ||

| Connecticut | 49 (10.8) | 48 (10.6) | |

| California | 99 (21.7) | 122 (27.0) | |

| North Carolina | 143 (31.4) | 135 (29.9) | |

| Massachusetts | 112 (24.6) | 85 (18.8) | |

| Texas | 53 (11.6) | 62 (13.7) | |

| alcohol use | 0.07 | ||

| yes | 235 (52.3) | 263 (58.4) | |

| no | 214 (47.7) | 187 (41.6) | |

| missing | 7 | 2 | |

| smoking history | 0.02 | ||

| ever | 261 (57.9) | 224 (49.8) | |

| never | 190 (42.1) | 226 (50.2) | |

| missing | 5 | 2 | |

| primary family history of meningioma | 0.002 | ||

| yes | 15 (3.3) | 2 (0.4) | |

| no | 441 (96.7) | 450 (99.6) | |

| education | <0.0001 | ||

| ≤high school | 124 (27.4) | 72 (16.0) | |

| ≥some college | 328 (72.6) | 378 (84.0) | |

| missing | 4 | 2 | |

| income | 0.25 | ||

| <$75,000 | 195 (48.5) | 186 (44.5) | |

| ≥$75,000 | 207 (51.5) | 232 (55.5) | |

| missing | 54 | 34 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.003 | ||

| <25 | 84 (18.6) | 130 (28.8) | |

| 25 to <30 | 207 (45.8) | 189 (41.9) | |

| 30 to <35 | 102 (22.6) | 79 (17.5) | |

| ≥35 | 59 (13.1) | 53 (11.8) | |

| missing | 4 | 1 | |

| yes | 15 (3.3) | 2 (0.4) | |

Endogenous Hormone Exposure

Hair patterning data from meningioma cases and controls are presented in Table 2. Overall, we did not detect significant differences between cases and controls in vertex or frontal baldness patterns at age 30 years. In an age- and race-adjusted multivariate analysis, we observed a weak increased risk for the association between vertex baldness patterns of Type V and greater; the adjusted OR was 1.30 with a CI that includes 1.0 (95% CI 0.76–2.20). Further multivariate analysis controlling for study site, education, smoking status, BMI, family history, and alcohol use did not substantially alter the results (data not shown). A test of interaction between BMI and vertex baldness also was not significant (p = 0.55) (data not shown). Significant case-control differences in BMI were observed, with male cases more likely to be overweight or obese compared with controls (Table 1, p = 0.003). As shown in Table 2, the age- and race-adjusted ORs for the association between BMI and case-control status show over a 1.5-fold to close to a 2-fold increased risk of meningioma for overweight and obese men, respectively. However, no differential effect was observed as the severity of obesity increased. Additional analyses, controlling for race, age, education, and study site did not result in an attenuation of the association between BMI and meningioma shown in Table 2 (data not shown)

TABLE 2.

Hormone exposure

| No. of Subjects (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Cases (n = 454) | Controls (n = 451) | OR (95% CI)* |

| endogenous hormone exposure | |||

| baldness (Norwood-Hamilton Scale) | |||

| none (I) | 263 (60.5) | 260 (61.8) | 1.00 (referent) |

| frontal baldness/mild vertex baldness (II, III, IIIvertex, IV) | 136 (31.3) | 134 (31.5) | 1.00 (0.74–1.34) |

| severe vertex baldness (>V) | 36 (8.3) | 27 (6.4) | 1.30 (0.76–2.20) |

| missing | 19 | 30 | |

| BMI (k/m2) | |||

| <25 (normal) | 84 (18.7) | 130 (28.9) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 25 to <30 (overweight) | 206 (45.8) | 188 (41.8) | 1.66 (1.17–2.34) |

| 30 to <35 (obesity I) | 102 (22.7) | 79 (17.6) | 1.92 (1.28–2.90) |

| ≥35 (obesity II) | 58 (12.9) | 53 (11.8) | 1.64 (1.02–2.64) |

| missing | 4 | 1 | |

| exogenous hormone exposure | |||

| ever use hormones | |||

| no | 424 (94.9) | 423 (94.2) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 23 (5.2) | 26 (5.8) | 0.86 (0.48–1.53) |

| missing | 7 | 2 | |

| ever receive LHRH | |||

| no | 442 (99.6) | 442 (98.7) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 2 (0.5) | 6 (1.3) | 0.33 (0.07–1.66) |

| missing | 10 | 3 | |

| ever take testosterone | |||

| no | 432 (97.1) | 429 (95.8) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 13 (2.9) | 19 (4.2) | 0.68 (0.33–1.40) |

| missing | 9 | 3 | |

| ever take antiandrogen | |||

| no | 441 (99.1) | 445 (99.8) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 3.82 (0.42–34.94) |

| missing | 9 | 5 | |

| ever use soy or tofu | |||

| no | 351 (78.7) | 289 (64.2) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 95 (21.3) | 161 (35.8) | 0.50 (0.37–0.68) |

| missing | 8 | 1 | |

| ever had orchiectomy | |||

| no | 432 (96.6) | 440 (97.8) | 1.00 (referent) |

| unilateral | 4 (0.9) | 5 (1.1) | 0.82 (0.22–3.10) |

| bilateral | 11 (2.5) | 5 (1.1) | 2.08 (0.72–6.06) |

| missing | 7 | 1 | |

| ever had a vasectomy | |||

| no | 337 (75.4) | 338 (75.1) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 110 (24.6) | 112 (24.9) | 0.95 (0.70–1.30) |

| missing | 7 | 1 | |

| ever use hair regrowth products | |||

| no | 414 (93.2) | 414 (92.2) | 1.00 (referent) |

| yes | 30 (6.8) | 35 (7.8) | 0.88 (0.53–1.47) |

| missing | 5 | 7 | |

Adjusted for age and race.

Discussion

Meningioma is less commonly diagnosed in males than in females. This is the first report to examine the role of endogenous and exogenous hormones in males. Most of the exogenous hormone exposures assessed in the study, including male pattern baldness, LHRH, antiandrogens, testosterone, orchiectomy, and vasectomy, were not found to be individually associated with the risk of meningioma in men. However, the prevalence of each of these exposures was low, and the power to detect an association was not adequate.

We did find that overweight and obese men had a significantly increased risk of meningioma compared with controls. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, the effects of BMIs being between 25 to less than 30 kg/m2 (p = 0.004) and 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 (p = 0.002) remain significant, with p values < 0.0045, while the association with a BMI 35 or greater is not (p = 0.05), most likely explained by the smaller sample size. A possible explanation is that higher BMI may be related to an increased endogenous estrogen exposure; the association with increased risk of meningioma in overweight and obese males is compatible with the higher incidence of meningioma observed in females than in males. Alternatively, obesity also increases exposure to inflammation and oxidative stress, which may explain the association with meningioma risk. Based on the data from this study, we cannot draw a definitive conclusion concerning the association with BMI and meningioma, and further study of diet, physical exercise, and other inflammation-related factors should be explored.

We also found a significant decreased risk of meningioma associated with ever use of soy and tofu dietary products, although we were not able to detect a case-control difference in the mean months of use. Even after correcting for multiple comparisons, this relationship remains significant (p < 0.0045). It has been suggested that dietary soy and tofu products might compete with endogenous estrogen in binding with the estrogen receptor. Soy or tofu products, considered a class of phytoestrogens or isoflavones, are structurally similar to 17β-estradiol and may bind estrogen receptors and modulate function.4 Due to antiproliferative, antiangiogenic, antioxidative, and antiinflammatory properties, it also has been shown that isoflavones act independently of estrogen receptors, providing other possible mechanisms to explain an inverse relationship with disease risk.4 Some epidemiological studies support a belief that isoflavones decrease the risk of breast cancer, perhaps by interacting with the estrogen receptor.5,15,17,19 One short-term, 6-month intervention study, however, was not able to show that soy isoflavones reduce breast epithelial proliferation.14 Alternatively, other healthy lifestyle factors correlated with tofu and soy intake may explain the association and may include other dietary constituents or exercise, which were not measured in our study.

There are some limitations of this analysis that should be considered. The exposure assessment of soy and tofu intake lacked precision since we did not obtain portion sizes or conduct a full dietary assessment. This likely led to dietary exposure misclassification and attenuation of the association since we would expect misclassification to be similar in cases and controls. We also were not able to detect case-control differences with months of use. Our inability to assess timing and dose effects reduced the power of our analyses. Assessment of male pattern baldness, using the Norwood-Hamilton Scale, requires no special training, and concordance between lay and expert scores or repeated ratings has been reported as 98% and 99%, respectively.16 However, no validation study has been performed to determine the validity and reliability of hair pattern data that are gathered retrospectively and by self-report.

In spite of some of these limitations, our study has a number of strengths including the use of population-based cases and controls and the inclusion of a number of covariates for which we were able to adjust in multivariate analyses.

Conclusions

In this first attempt to address the association between hormonal factors and the risk of meningioma in males, many of the hormone-related factors we examined were not found to be significantly associated with the risk of meningioma. However, the observed increased risk associated with obesity suggests that exposure to endogenous estrogen may increase the risk of meningioma, though other possible explanations cannot be ruled out. The decreased risk of meningioma associated with soy and tofu intake suggests a possible role of estrogen-like exposures that may compete with endogenous estrogen or possibly act as an antiproliferative agent in reducing the risk of meningioma, which warrants further study. Further study of dietary and lifestyle factors is needed. Meningioma is a disease with a high morbidity, and the identification of modifiable exposures that reduce the risk has important public health implications.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BMI

body mass index

- HRT

hormone replacement therapy

- LHRH

luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone

References

- 1.Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279–282. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll RS, Zhang J, Black PM. Expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in human meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 1999;42:109–116. doi: 10.1023/a:1006158514866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll RS, Zhang J, Dashner K, Sar M, Wilson EM, Black PM. Androgen receptor expression in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:453–460. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.3.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho JH, Lee HC, Lim DJ, Kwon HS, Yoon KH. Mobile communication using a mobile phone with a glucometer for glucose control in Type 2 patients with diabetes: as effective as an Internet-based glucose monitoring system. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15:77–82. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.080412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho YA, Kim J, Park KS, Lim SY, Shin A, Sung MK, et al. Effect of dietary soy intake on breast cancer risk according to menopause and hormone receptor status. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:924–932. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claus EB, Black PM, Bondy ML, Calvocoressi L, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL, et al. Exogenous hormone use and meningioma risk: what do we tell our patients? Cancer. 2007;110:471–476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL, Wrensch M. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530–4537. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL, Wrensch M. Family and personal medical history and risk of meningioma. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:1072–1077. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.JNS11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, Wrensch M, Wiemels JL, Schildkraut JM. Exogenous hormone use, reproductive factors, and risk of intracranial meningioma in females. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:649–656. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.JNS12811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claus EB, Walsh KM, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, Wrensch M, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of meningioma: the effect of gender. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:943–950. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005–2009. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(Suppl 5):v1–v49. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis JA, Sinclair R, Harrap SB. Androgenetic alopecia: pathogenesis and potential for therapy. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2002;4:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402005112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu DW, Efird JT, Hedley-Whyte ET. Progesterone and estrogen receptors in meningiomas: prognostic considerations. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:113–120. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.1.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan SA, Chatterton RT, Michel N, Bryk M, Lee O, Ivancic D, et al. Soy isoflavone supplementation for breast cancer risk reduction: a randomized phase II trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:309–319. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SA, Shu XO, Li H, Yang G, Cai H, Wen W, et al. Adolescent and adult soy food intake and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1920–1926. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norwood OT. Male pattern baldness: classification and incidence. South Med J. 1975;68:1359–1365. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trock BJ, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R. Meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:459–471. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiemels JL, Wrensch M, Sison JD, Zhou M, Bondy M, Calvocoressi L, et al. Reduced allergy and immunoglobulin E among adults with intracranial meningioma compared to controls. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1932–1939. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Pike MC. Epidemiology of soy exposures and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:9–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]